The aim of this research is to investigate the mediator role of coping competence on the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing. Participants were 284 university students who completed a questionnaire package that included the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale, the Coping Competence Questionnaire, and the Flourishing Scale. The relationships between coping competence, mindfulness, and flourishing were examined using correlation and regression analysis. According to results, both coping competence and flourishing were predicted positively by mindfulness. On the other hand, flourishing was predicted positively by coping competence. In addition, coping competence mediated on the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing. Together, the findings illuminate the importance of mindfulness on psychological and cognitive adjustment. The results were discussed in the light of the related literature and dependent recommendations to the area were given.

El objetivo de esta investigación es estudiar el papel mediador del afrontamiento de la competencia en la relación entre la concienciación y el florecimiento. Participaron 284 estudiantes universitarios que rellenaron un paquete de cuestionarios que incluía la Escala de Concienciación Cognitiva y Afectiva, el Cuestionario de Afrontamiento de la Competencia, y la Escala de Florecimiento. Se examinaron las relaciones entre el afrontamiento de la competencia, la concienciación y el florecimiento utilizando un análisis de correlación y regresión. De acuerdo con los resultados, tanto el afrontamiento de la competencia como el florecimiento fueron predichos de manera positiva por la concienciación. Por otro lado, el florecimiento fue predicho positivamente por el afrontamiento de la competencia. Además, el afrontamiento de la competencia medió en la relación entre la concienciación y el florecimiento. En conjunto, los hallazgos ilustran la importancia de la concienciación en el ajuste psicológico y cognitivo. Se analizaron los resultados a la luz de la literatura relacionada, otorgándose las recomendaciones dependientes del área en cuestión.

Mindfulness was derived from Buddhist meditation traditions which maintain that the regular practice of mindfulness meditation reduces suffering and enhances positive qualities such as insight, wellbeing, openness, wisdom, equanimity, and compassion (Baer, Lykins, & Peters, 2012) by facilitating emotional regulation (Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, & Laurenceau, 2007; Kumar, 2002). It has been adopted in contemporary psychology as an approach for increasing awareness and responding skillfully to mental processes that contribute to emotional distress and maladaptive behavior (Bishop et al., 2004). Mindfulness was described firstly by Kabat-Zinn (1994, 2005) as an awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experiences, including emotions, cognitions, and bodily sensations, as well as external stimuli such as sights, sounds, and smells moment to moment. Within this notion, mindfulness was considered as contrasted with excessive rumination about the past or future, negative self-evaluation and behaving in a reactive way (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Moore, 2008). Because it prevents habitual reacting and encouraging a more adaptive deliberate response to experiences (Baer, Smith & Allen, 2004; Segal, Williams & Teasdale, 2002), mindfulness is also believed to enhance affective balance and psychological well-being (Schroevers & Brandsma, 2010).

More recently, the definition of the construct has been extended by Bishop et al. (2004) as being composed of two main elements: paying attention to one's present moment experience as it is happening (self-regulation of attention) and adoption of a particular orientation towards one's experiences. Self-regulation of attention allows an individual for increased recognition of mental events in the present moment and refers to non-elaborative observation and awareness of thoughts, feelings, or sensations from moment to moment (Keng, Smoski & Robins, 2011). This kind of attention requires both the ability to concentrate on what is actually occurring and the ability to intentionally move attention from one aspect of the experience to another. The second dimension, orientation to experience, includes adopting a particular orientation towards one's experiences in the present moment and relating to this experience with a curious, open, and accepting stance (Bishop et al., 2004; Feldman et al., 2007; Neff & Germer, 2013) which, in turn, allows people to experience events fully, without resorting to either extreme of excessive preoccupation with, or suppression of, the experience (Keng et al., 2011).

Mindfulness facilitates acknowledging emotions as transient phenomena and fully experiencing emotions without necessarily acting upon them (Kabat-Zinn, 1994), thus providing higher levels of emotional intelligence (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Feldman et al., 2007). Mindfulness is considered as a potentially effective antidote against common forms of psychological distress, many of which involve the maladaptive tendencies to suppress, over-engage with, or avoid one's distressing thoughts and emotions (Hayes & Feldman, 2004; Keng et al., 2011). Non-mindful approaches to internal experiences, on the other hand, have been characterized as underor over-engagement with internal experiences (Buchheld, Grossman & Walach, 2002; Feldman et al., 2007; Hayes & Feldman, 2004). The former, emotional under-engagement, is related mainly experiential avoidance and thought suppression while the latter, over-engagement, involves one's exaggeration or elaboration of initial symptoms of distress such as worry, rumination, and over-generalization (Feldman et al., 2007).

The past two decades have seen an explosion of research into the benefits of mindfulness (Neff & Germer, 2013) and an ample of evidence has shown that it has positive psychological, social, and cognitive effects on people's daily life. These studies found mindfulness to be associated positively with subjective well-being, behavioral regulation, reduced negative symptoms and emotional reactivity (Keng et al., 2011), cognitive flexibility, mood repair, clarity of feelings (Feldman et al., 2007), self-esteem, life satisfaction, positive affect, and optimism (Brown & Ryan, 2003). On the contrary, mindfulness was related negatively to distress, anxiety, depression (Cash & Whittingham, 2010; Feldman et al., 2007), social anxiety (Rasmussen & Pidgeon, 2011), negative affect, worry, rumination, and brooding (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Feldman et al., 2007).

Coping competenceThe coping competence theory proposes that challenges can be classified into three domains (Moreland & Dumas, 2008); affective (challenges requiring solutions to primarily emotional situations and demands), social (challenges mainly related with interpersonal and social situations and demands), and achievement (challenges linked to significant goal-directed activities, e.g., physical and cognitive abilities and academic or work-related demands and responsibilities). Coping competence has been conceptualized by Schroder and Ollis (2013) as a trait-like protective factor against the development of helplessness-based depression and has been defined as “the capacity to effectively cope with negative life events and failure as indicated by a reduced likelihood of helplessness reactions and fast recovery from any occurring helplessness symptoms” (p. 288).

Coping competence is considered related to course of development while people display different levels of coping skills as a function of sex and age (Compas, Conner-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen & Wadsworth, 2001). Girls, often at an earlier age, typically show greater levels of coping competence especially in the affective and social domains than boys (Moreland & Dumas, 2008). Studies consistently demonstrated that coping competence has high negative correlations with depression, neuroticism, stress reaction, alienation, dysfunctional coping, external-fatalistic health locus of control (Schroder, 2004; Schroder & Ollis, 2013), and parental child abuse potential (Lopez, Beglea, Dumas & de Arellanoa, 2012) and positive correlations with well-being, emotion-focused coping (Schroder & Ollis, 2013), life orientation, self-efficacy beliefs, and internal health locus of control (Schroder, 2004). Also, Schroder (2004) has found in her study that coping competence buffers the effects of symptom stress on depression and that symptom stress is strongly related to depression among patients who were low in coping competence only. On the other hand, it has been shown that depression was low and unaffected by symptom stress among patients high in coping competence (Schroder, 2004).

FlourishingMore recently, there has been an intense interest in positive psychology trend, which pays attention to personal strengths and how they contribute to psychological well-being. This notion suggested that psychological research should care about building the best qualities in life instead of repairing the worst ones (Gable & Haidt, 2005). In this context, the most important contribution of positive psychology may be understanding and encouraging human flourishing (Seligman & Czikszentmihalyi, 2000) that was defined as living within an optimal range of human functioning, performance, generativity, and growth (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005; Larsen & Prizmic, 2008). Individuals with a high level of flourishing have emotional vitality, function positively in both private and social life, and are free of mental illness (Michalec, Keyes & Nalkur, 2009). These people are willing to develop, improve, and expand their potential as a person, and are able to develop warm, trusting relationships with others (Diener et al., 2010). Flourishing individuals are also more likely to enjoy better social relationships, experience less limitations on daily activities (Huppert, 2009; Keyes, 2005), and contribute to their communities (Huppert, 2009; Michalec et al., 2009). Moreover, flourishing individuals experience both negative (e.g., anger, fear, and irritation) and positive emotions (e.g., inspired, hopeful, and optimistic) and have adaptive coping strategies more than those who were languishing or depressed (Faulk, Gloria & Steinhardt, 2013).

Studies have shown that flourishing is positively related to psychological, emotional, and social well-being (Keyes, 2002), positive emotional reactivity, mindfulness (Catalino & Fredrickson, 2011). They were also found to be associated with greater environmental control, positive relations with others, life purposes, personal development (Telef, 2011), relatedness, competency, self-acceptance, autonomy, and low level of loneliness (Diener et al., 2010) and depression (Keyes, 2005). Other studies have demonstrated the correlations of flourishing with indicators of cognitive well-being, such as realizing potentials in different aspects of life and trying to achieve (Gokcen, Hefferon & Attree, 2012), perceiving that life is going well (Huppert & So, 2009), and better life expectancy and life purpose (Huppert, 2009; Telef, 2011).

Mindfulness, coping competence, and flourishingThe ability to cope effectively with life's stressors is crucial for individuals and therefore plays an important role in development of the major life skills. Coping competently with life's stressful situations is shaped by the values, beliefs and everyday practices, is a major part of successful performance (Hardy, Jones & Gould, 1996; Nicolas & Jebrane, 2008), and as individuals learn to cope with life crises they may easily build a repertoire of abilities that can be used to manage crises that emerge later in life. Since coping competence requires cognitive-behavioural flexibility and a non-reliance on behavioural automaticity and emotional reactivity, mindfulness may facilitate coping competence by providing increased awareness and tolerance of painful or distressful emotions (Baer, 2003). Moreover Shapiro, Carlson, Astin and Freedman (2006) have proposed that mindfulness ensures the skill of reperceiving, and thereby people are able to take the time to consider distressful experiences objectively without activating negative affective states associated with the event which allows them to consider a much larger range of coping resources or strategies as well, namely coping competence. In addition, when individuals are forced to experience distressing situations, mindfulness may facilitate coping competence and thus alleviate the negative consequences on well-being. Conversely, people low in mindfulness are more likely to react in ways that lead to psychopathology instead of coping competence, and this may damage their feelings of flourishing (Thomas, 2011).

Moreover mindfulness indicates to paying attention to one's present moment experience as it is happening (self-regulation of attention) and adoption of a particular orientation towards one's experiences (Bishop et al., 2004). This kind of attention provides a non-elaborative observation and awareness of thoughts, feelings, or sensations from moment to moment (Keng et al., 2011), while orientation to experience contributes to relating to one's experiences with a open, curious, and accepting stance (Bishop et al., 2004; Feldman et al., 2007; Neff & Germer, 2013). This in turn helps people to experience events fully, without resorting to either extreme of excessive preoccupation with, or suppression of, the experience (Keng et al., 2011). As mindfulness has a phenomenological centrality; it is considered as a significant indicator of flourishing. Regarding its extensive influences and concomitants, it may be proposed that to the extent that people have higher levels of mindfulness which plays an important role in protecting them against psychological distress (Hayes & Feldman, 2004; Keng et al., 2011) then they can experience higher level of sense of flourishing.

Considering the relationships of mindfulness, coping competence, and flourishing with positive mental health indicators, it seems possible that coping competence may be enhanced by mindfulness and thus it also may help to improve flourishing. In the light of the reciprocal relationships between mindfulness, coping competence, and flourishing with adaptive and maladaptive constructs which have been demonstrated by previous studies, mindfulness may influence flourishing via coping competence. The goal of this study is to explore this mediating effect as well as the associations of mindfulness, coping competence, and flourishing. In this study it was hypothesized that as mindfulness increases, flourishing may increase or vice versa and that coping competence may have a mediating role in this relationship. This study poses the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Mindfulness is positively associated with coping competence.

Hypothesis 2: Mindfulness is positively associated with flourishing.

Hypothesis 3: Coping competence is positively associated with flourishing.

Hypothesis 4: Coping competence mediates the link between mindfulness and flourishing.

MethodParticipantsParticipants were 284 university students (157 women, 127 men) who enrolled in various undergraduate programs at Sakarya University Faculty of Education, Turkey. These programs were science education (n = 66), mathematics education (n = 45), psychological counseling and guidance (n = 52), Turkish education (n = 60), and pre-school education (n = 61). Of the participants, 76 were first-year students, 60 were second-year students, 84 were third-year students, and 64 were fourth-year students. Their ages ranged from 18 to 27 years and GPA scores ranged from 2.07 to 3.65.

MeasuresCognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R) (Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson & Laurenceau, 2007). The scale consists of 10 items (e.g., “I can usually describe how I feel at the moment in considerable detail”) and each item is answered on a 1-4 scale that ranges from rarely/not at all to almost always. The total score of the CAMS-R is obtained by computing the sum of all items. Higher scores on the scale suggest higher levels of mindfulness. The Turkish adaptation of this scale had been done by Çatak (2012). The internal consistency coefficient of the scale was .77 and the corrected item-total correlations ranged from .21 to .60. The goodness of fit indexes from confirmatory factor analysis were: χ2 = 87.5, df = 30, RMSEA = .08, CFI = .91, and GFI = .94. Factor loadings ranged from .31 to .89.

Coping Competence Questionnaire (Schroder & Ollis, 2013). Coping competence scale consist of 12 items (e.g., “If I do not instantly succeed in a matter, I am at a loss”) 6-point Likert response scales ranging from 1 (“very uncharacteristic of me”) to 6 (“very characteristic of me”). Items were reversed and summed, with high scores indicating higher level of coping competence. The Turkish adaptation of this scale had been done by Akin et al. (2014). The internal consistency coefficient of the scale was .89 and the corrected item-total correlations ranged from .35 to .70. The goodness of fit indexes from confirmatory factor analysis were: χ2 = 123.98, df = 44, RMSEA = .082, CFI = .95, IFI = .95, NFI = .92, and SRMR = .062.

Flourishing Scale (Diener et al., 2010). The scale consists of 8 items (e.g., “I am competent and capable in the activities that are important to me”) and each item is answered on a 1-7 scale that ranges from strong disagreement to strong agreement. A sum of all score yields a total score ranges from 8 to 56 and higher score indicated that respondents view themselves in positive terms in important areas of functioning. The Turkish adaptation of this scale was prepared by Akin and Fidan (2012). The internal consistency coefficient of the scale was .83 and the corrected item-total correlations ranged from .47 to .67. The goodness of fit indexes from confirmatory factor analysis were: χ2 = 48.80, df = 18, RMSEA = .066, NFI = .97, CFI = .98, IFI = .98, RFI = .96, GFI = .97, and SRMR = .038. Factor loadings ranged from .60 to .78.

Procedure and statistical analysisFirstly permission for administration of the scales to the participants was obtained from related chief departments. Then participants were informed of the purpose and of the voluntary nature of study and were ensured anonymity for all responses given. Willing participants signed a consent form and returned the completed survey to the researcher. Self-report questionnaires were administered in a quiet classroom setting and the scales were administered to the students in groups in the classrooms. Aside from the demographic form, which came first, the order of measures was counterbalanced in administration to avoid ordering effect. The Pearson correlation coefficient and hierarchical regression analyses were used to determine the relationships among mindfulness, coping competence, and flourishing. In order to test whether coping competence mediated the link between mindfulness and flourishing with hierarchical regression analyses, Baron and Kenny's (1986) recommendations were followed. These analyses were carried out via SPSS 13.0.

This model was tested using the Sobel z test (Sobel, 1982). The purpose of this test is to verify whether a mediator carries the influence of an interdependent variable to a dependent variable. The Sobel z test is characterized as being a restrictive test, and as such, it assures that the verified results are not derived from collinearity issues. The test value verified in this study was significant (Z = 3.08645977; p < .001), showing that coping competence significantly carries the influence of mindfulness to flourishing.

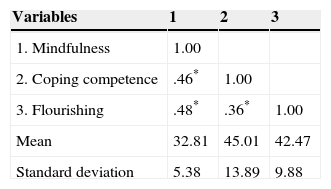

ResultsDescriptive data and inter-correlationsTable 1 shows the means, descriptive statistics, inter-correlations, and internal consistency coefficients of the variables used.

Upon examining Table 1, it is seen that there are significant correlations between mindfulness, flourishing, and coping competence. Mindfulness related positively to flourishing (r = .48) and to coping competence (r = .46). On the other hand, flourishing was found to be positively (r = .36) related to coping competence.

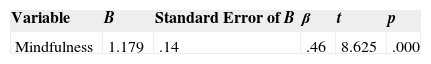

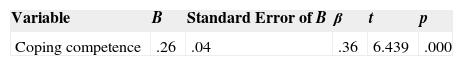

Testing the mediating role of coping competence in the relationship between mindfulness and flourishingFollowing the steps of the mediation procedure, firstly it was verified that mindfulness and coping competence were positively related (β = .46; t = 8.625; p < .01). The results are shown in Table 2. Then it was verified that coping competence and flourishing revealed a positive relationship (β = .36; t = 6.439; p < .01). The results are presented in Table 3.

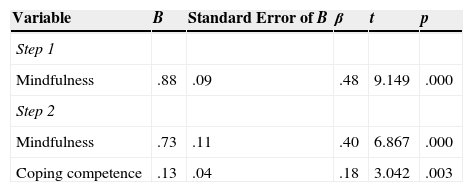

To test the third and last steps of mediation procedure, hierarchical regression analysis was done. The results of the hierarchical regression analysis demonstrated that mindfulness was positively associated with flourishing (β = .48; t = 9.149; p < .001). However, when coping competence and mindfulness were taken together in the regression analysis, the significance of the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing (β = .40; t = 6.867; p < .01) decreased, yet the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing was significant. According to Baron and Kenny (1986), this result indicated a partial mediation. Therefore, it can be said that the coping competence partially explains the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing. The results are presented in Table 4.

The hierarchical regression results of testing the mediational role of coping competence in the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing.

| Variable | B | Standard Error of B | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||||

| Mindfulness | .88 | .09 | .48 | 9.149 | .000 |

| Step 2 | |||||

| Mindfulness | .73 | .11 | .40 | 6.867 | .000 |

| Coping competence | .13 | .04 | .18 | 3.042 | .003 |

Dependent variable: flourishing. R2 = .23, adjusted R2 = .23 (p < .05) for Step 1; R2 = .25, adjusted R2 = .25 (p < .05) for Step 2.

This research aimed to investigate the mediating effect of the coping competence on the associations of mindfulness and flourishing. The findings showed that there were significant relationships among these variables. As expected, results demonstrated that the relationship between mindfulness and flourishing was partially mediated by coping competence. In other words, as mindfulness increases in this model, flourishing also increases and coping competence plays a mediating role in that increase.

In having a high level of coping competence, an individual will also have higher levels of well-being, emotion-focused coping, life orientation, self-efficacy beliefs, and internal health locus of control and low level of stress reaction, alienation, neuroticism, dysfunctional coping, external-fatalistic health locus of control (Schroder, 2004; Schroder & Ollis, 2013), and thus they may have feel flourish more. Similarly mindful individuals feel more positive affect (Brown & Ryan, 2003), are less reactive to emotionally threatening stimuli (Creswell, Way, Eisenberger & Lieberman, 2007), tend to be more optimistic, to endorse more positive self-views (Aspinwall & Richter, 1999), and to engage in more active coping strategies (i.e., problem solving) (Weinstein, Brown & Ryan, 2009). This in turn helps an individual with high level of mindfulness to perceive him/ herself as a “flourished” person (Ryan & Frederick, 1997) and to have more coping competence.

There are several limitations of this study that should be taken into account when evaluating the findings. Firstly, as findings obtained in this study may be influenced by university students’ academic (difficulty of courses), social (intimate relations, loneliness, ostracism, living away from the family), financial (problems related to money), and psychological problems, these results should not be generalized to other populations and further study is required targeting other populations. Secondly, as correlational statistics were utilized, no definitive statements can be made about causality. Thirdly, the data reported here are limited to self-reported data and did not use a qualitative measure of these variables. Lastly, the results of this research must be considered as exploratory and preliminary; thus it is difficult to give a full explanation related to causality among the variables examined in the research, because correlational data were used.

In conclusion, this investigation shows that mindfulness affects flourishing both directly and indirectly via coping competence. People who have higher level of mindfulness are more likely to be high in coping competence and flourishing. Implications of these findings show that mindfulness and coping competence play a key role in supporting psychological well-being. Mental health professionals may conduct programs to help university students to have more coping competence and mindfulness and ultimately to increase flourishing. Furthermore, mindfulness-based interventions (e.g., Segal et al., 2002) may be effectively used by educators and counselors to teach individuals to recognize and attend to distressing thoughts and emotions and to disengage from automatic dysfunctional thoughts and behavioural patterns such as rumination and avoidance (Schroevers & Brandsma, 2010) which negatively influence coping competence. Clearly, however, more research needs to be done to understand how cognitive variables such as coping competence and mindfulness are linked to psychological well-being. Lastly, future research should consider other cognitive and emotional variables that may moderate the relationships of mindfulness with flourishing.