We report the case of a 76-year-old man, with unknown medical history, who died suddenly. The autopsy showed a ruptured thoracic aneurysm as the cause of death. As incidentaloma there was a tumor of the left adrenal gland that after histopathological study corresponded to myelolipoma. The differential diagnosis with other adrenal tumors, their possible complications and their degree of participation in the death of the subject are considered.

Se expone el caso de un varón de 76 años, con antecedentes médicos desconocidos, que fallece de forma repentina. En la autopsia se observa la rotura de un aneurisma arterioesclerótico de la aorta torácica como causa de la muerte. Como incidentaloma, destaca una tumoración de la glándula suprarrenal izquierda que, tras el estudio histopatológico, se corresponde con un mielolipoma. Se plantea el diagnóstico diferencial con otros tumores adrenales, sus posibles complicaciones y su grado de participación en la muerte del sujeto.

Adrenal gland tumours are rare, generally being discovered incidentally during imaging studies or autopsies. They are classified according to their biological behaviour as benign and malignant, and according to their endocrinological activity, as functioning (if they secrete hormones) and silent. Seventy-five percent of these tumours are usually benign, non-functioning adenomas, and approximately 3% are myelolipomas. In autopsy series, adrenal lesions are observed in 9% of normotensive patients and 12% of hypertensive patients. The prevalence has increased due to the rise of imaging tests.1

The adrenal glands, located in the retroperitoneum, are often overlooked during forensic autopsies. A protocolised study of these glands enables the detection of adrenal tumours that could aid the understanding of the pathophysiological mechanism of certain types of deaths that are initially presented as suspected criminal offences.

Medical-forensic descriptionA 76-year-old man had been living alone for months in a campsite. His medical history was unknown, except for treatment with enalapril for high blood pressure. According to a friend, he had lost weight over the past year due to an unspecified viral infection. He requested help from his friend shortly before his death.

The forensic autopsy was performed 36 h after his death. External examination revealed a man of thin build (BMI: 18.1 kg/m2) with no signs of violence. There was a green stain (12 x 5 cm) in the right iliac fossa.

Internal examination revealed a ruptured atherosclerotic aneurysm of the thoracic aorta (14 x 7 cm) in its proximal third, with wall dissection, perforation, and haemorrhage, reaching adjacent soft tissues from the cervical region to the diaphragm, and a left hemothorax (300 cc). The heart (510 g) was enlarged in weight and size due to hypertensive hypertrophic heart disease, with a whitish lesion in the left ventricle, consistent with an old myocardial infarction. It showed signs of aortic valve disease (degenerative stenosis). The lungs appeared congested, with emphysematous areas. In both the parietal and visceral pleura, the pericardium, the dome of the diaphragm, and whitish plaques of hard consistency are observed. Microscopically, they appeared to be hyalinised fibrinous material, but no specific deposits were visible. Therefore, the diagnosis reported was pneumoconiosis, possibly asbestosis.

In the abdominal cavity, another atherosclerotic aneurysm (12 x 7 cm) was identified in the abdominal aorta, at the bifurcation of the renal arteries. It was thrombosed, with no wall rupture and with the presence of organised thrombi. A saddle thrombus was seen at the bifurcation of the iliac arteries. The liver showed chronic passive congestion with a nutmeg pattern; the left kidney showed a small 8-mm focus of old infarction; the spleen and pancreas showed autolytic changes. The intestinal loops showed numerous whitish, millimetric lesions, up to 1 cm in size, on the external surface of the small intestine and in the mucosa. When sectioned, milky contents were observed, and microscopically, dilated vascular structures were observed, leading to a diagnosis of lymphangiectasia.

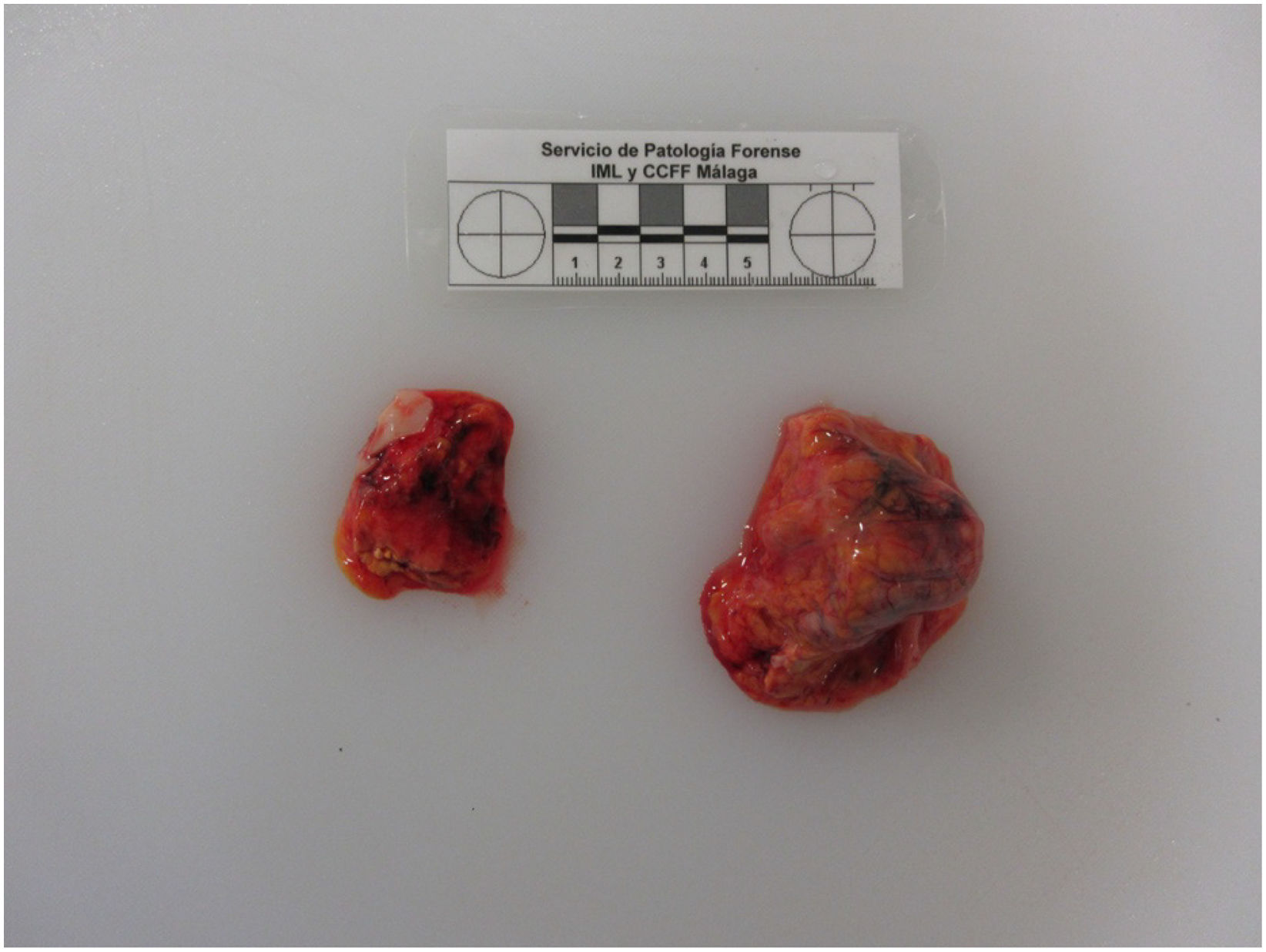

The adrenal glands were striking in their asymmetry (Fig. 1): the left gland weighed 50 g and measured 5 x 3.5 x 3.5 cm; the right gland weighed 10 g and measured 2.5 x 2 x 1.5 cm (average expected weight of both: 11.5 g). The left section had a heterogeneous appearance, with haemorrhagic and fibrous areas (Fig. 2). Microscopically, an old haemorrhagic infarct with areas of recent and old haemorrhage, with calcifications and recanalisation, was observed over a tumour with adipose tissue and erythroid foci, as well as precursors of the white blood cell series, indicating an infarcted adrenal myelolipoma (Fig. 3).

Background blood and mature adipocytes with myeloid (black arrow) and erythroid (green arrow) nests, immature cellularity reminiscent of bone marrow (H&E, 20x). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

It was concluded that this was a natural death, with the (immediate) cause being internal haemorrhage in the mediastinum and thorax, due to a ruptured arteriosclerotic aneurysm of the thoracic aorta (fundamental) artery.

DiscussionAdrenal incidentalomas are defined as an asymptomatic adrenal mass, 1 cm or greater in size, detected on imaging tests performed for an unrelated indication.2 Incidence is 0.5%–1% on abdominal imaging tests (CT, MRI) in patients over 40 years of age.3 These lesions can present as adenomas (60%–70%), carcinomas (2%–3%), pheochromocytomas (1%), metastases (2.5%), myelolipomas (6%–16%),3–5 and other benign tumours such as ganglioneuromas, cysts, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, and schwannomas (1%). The increased use and improved quality of imaging techniques have allowed for an increase in diagnosis, with the prevalence increasing from 1% to 8%.6 In the case we present, the discovery of the adrenal mass was incidental during the forensic autopsy in a patient with an unknown medical history. Macroscopic and microscopic examination led to the diagnosis of myelolipoma. This is a rare benign tumour of the adrenal gland, with a prevalence of 0.2% in autopsies, and which presents a combination of myeloid and adipose tissue.7 They are usually diagnosed at approximately the age of 51 years. There is no significant difference by sex and they tend to be more frequent on the right side, possibly due to the greater possibility of friction with the lower border of the liver.4 Myelolipomas are classified as giant when the size is greater than 10 cm, associated with compressive symptoms.8 They are usually asymptomatic tumours, but they can manifest as abdominal pain (22.5%), flank pain (13.5%) or abdominal discomfort.7 Cases of spontaneous rupture and internal haemorrhage are rare, the risk being higher in tumours larger than 6 cm.7 Most incidentalomas are benign and non-secreting, but up to 20–30% present hormonal hypersecretion, cortisol being the most frequent.2 In myelolipomas, hormonal dysfunction occurs in 7% of cases, with mechanical irritation being the most accepted hypothesis.7 In forensic cases, the post-mortem interval and the location of sample collection make it difficult to interpret biochemical parameters, and analysis of cortisol and catecholamines in urine is recommended due to their instability in blood.9,10

In this case, the myelolipoma was not a giant, left-sided lesion, in a 76-year-old man and does not match the most common presentation. In forensic pathology, we often encounter blind autopsies, where the deceased's medical history is unknown. A thorough examination of the body, including a survey of family members and access to the patient's medical history, is essential. Our patient had hypertension, but the cause of this condition (primary or secondary to adrenal disorders) is unknown. In up to 32.8% of cases with myelolipoma, the patients are hypertensive, and it usually resolves after surgery.11

Although the cause of death was established after the autopsy, we believe a standardised and complete autopsy by the forensic pathologist is necessary, including macroscopic and microscopic examination of the adrenal glands. The absence of this examination can lead to an error in the interpretation of the pathophysiological mechanism of death or even its cause. In clinical practice, diagnosis is usually made through imaging techniques and hormonal studies, tests that are not always available to the forensic pathologist, but which can be supplemented by an autopsy. In cases of retroperitoneal haemorrhage, a differential diagnosis of spontaneous rupture of a myelolipoma should be made with the most common conditions (aneurysm, dissection) at this level. In this case, despite the presence of an aneurysm in the abdominal aorta, there was no rupture of the tumour or retroperitoneal haemorrhage.

Another aspect to be considered by the forensic pathologist is the study of the underlying cause of the high blood pressure, since in up to 32.8% of patients with myelolipoma, this is the cause of the condition.

Although myelolipoma is a rare adrenal tumour, it should be considered to rule out complications arising from it, both as a cause of sudden death and as a role in other pathological processes.

FundingThe authors declare that this research did not receive any specific grants from public or private entities.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Martín Cazorla F, Tirado Pascual M, Ranea Jimena SA, López García M. Infarcted adrenal myelolipoma: Finding in a pluripathologic patient. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remle.2025.500462.