In developing countries, mortality from breast cancer (BC) is higher due to changes in lifestyle that produce a rise in incidence, with over half of patients receiving advanced-stage diagnoses. Young girls have a significant impact on women's knowledge and awareness of BC in their communities and their motivation needs to be evaluated.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to assess the level of knowledge of BC regarding potential risk factors, awareness about the most common warning signs, diagnostic and screening, and perceptions towards BC treatment outcomes among young adult girls in Northern Cyprus.

MethodsA cross-sectional, observational study was conducted among young adult girls in three major provinces of Northern Cyprus: Nicosia, Kyrenia, and Famagusta, using a structured, validated questionnaire with five parts.

ResultsA total of 300 young adult girls were enrolled in this study, with a mean age of 22.37 years. There was a significant lack of knowledge about BC risk factors and diagnosis (score = 8.4, P < 0.0001); (score = 5.7, P < 0.0001, respectively). There was also a significant lack of awareness of the BC signs (score = 6.6, P < 0.0001), and perceptions towards treatment (score = 5.3, P < 0.0001).

ConclusionThis study found that most young adult girls in Northern Cyprus had lower than expected knowledge of BC risk factors, warning signs, and early cancer diagnosis and screening. The study population, on the other hand, had fairly positive perceptions of BC management.

En los países en desarrollo, la mortalidad por cáncer de mama (CM) es mayor debido a los cambios en el estilo de vida que producen un aumento en la incidencia, con más de la mitad de las pacientes recibiendo diagnósticos en estadio avanzado. Las jóvenes tienen un impacto significativo en el conocimiento y la concienciación de las mujeres sobre el CM en sus comunidades, y es necesario evaluar su motivación.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar el nivel de conocimiento sobre el CM en relación con los posibles factores de riesgo, el conocimiento de las señales de alerta más comunes, el diagnóstico y la detección, y las percepciones sobre los resultados del tratamiento del CM entre las jóvenes adultas del norte de Chipre.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio observacional transversal entre jóvenes adultas de tres provincias principales del norte de Chipre: Nicosia, Kyrenia y Famagusta, utilizando un cuestionario estructurado y validado de cinco partes.

ResultadosSe inscribieron en este estudio 300 jóvenes adultas, con una edad media de 22,37 años. Se observó una falta significativa de conocimiento sobre los factores de riesgo y el diagnóstico del CM (puntuación = 8,4, P < 0,0001). (puntuación = 5,7, P < 0,0001, respectivamente). También se observó un desconocimiento significativo de los signos del cáncer de mama (puntuación = 6,6, P < 0,0001) y de la percepción del tratamiento (puntuación = 5,3, P < 0,0001).

ConclusiónEste estudio reveló que la mayoría de las jóvenes del norte de Chipre tenían un conocimiento inferior al esperado sobre los factores de riesgo del cáncer de mama, las señales de alerta, el diagnóstico y la detección precoces. Por otro lado, la población del estudio tenía una percepción bastante positiva del manejo del cáncer de mama.

Breast cancer (BC) is the world's second most frequent malignancy, trailing only lung cancer. It accounts for approximately 24.5% of all cancer cases and 15.5% of cancer deaths in women, ranking first in incidence and mortality in the majority of countries.1 BC incidence is increasing among young adult girls in most countries and remains a serious concern in developing countries.2 The mortality rate from BC is increased in developing countries because lifestyle changes lead to increased incidence with more than half of patients diagnosed with advanced stages.3,4 Moreover, delays in diagnosis and treatment of BC from the time of initial detection are linked to increased tumour size and worse long-term outcomes.5 BC is influenced by several potential risk factors associated with a steady increase in incidence, including family history of the disease, genetic predisposition, obesity, reduced physical activity, alcohol consumption, ageing, tobacco smoking, a high-fat diet, a high-dose chest X-ray, and hormonal changes.2,6,7

Despite significant advances in BC treatment, the prognosis remains poor in developing countries, particularly related to delayed diagnosis.8 BC is thought to have a better prognosis and lower morbidity and mortality when detected early. Early diagnosis and screening are two significant options for early detection of BC since they raise the likelihood of a low-cost recovery with few comorbidities.9 On the other side, screening uses simple investigations to find cancer patients before they show symptoms. Mammography, clinical breast examinations (CBEs) and self-breast examination (SBE) are secondary preventive techniques used to identify BC early.10 Understanding the possible risk factors for BC and being aware of the warning signals are crucial for early detection and prevention, and mortality reduction. Therefore, high knowledge and awareness are essential for the success and effectiveness of cancer treatment programmes.

Previous literature has mainly focused on the knowledge, perceptions, and cancer risk behaviours of adults and older age groups.11–13

Young adult girls are a vulnerable population, as they might not consider their behaviours to carry BC-related risk. This is related to insufficient cancer awareness and commitment to risky health behaviours and habits, such as alcohol consumption and smoking. Therefore, it is essential for planning and targeting efforts to reduce the prevalence of harmful risk factors and delay the long-term cancer incidence rates among this population.14,15 It is acknowledged that even among youth, there is a lack of understanding regarding BC, which makes it challenging to diagnose the disease early and provide appropriate therapy.16 By providing young adult girls with information about early detection methods and their associated benefits, they can improve their skills in performing SBE and expand their role as client educators. Furthermore, young adult girls have a significant impact on women's awareness of these cancers in their communities and their motivation to be evaluated.17 From this perspective, the aim of this study was to assess the level of knowledge of BC regarding potential risk factors, awareness about the most common warning signs, diagnostic and screening, and perceptions towards BC treatment outcomes among young adult girls in Northern Cyprus.

Materials and methodsStudy design and settingThis cross-sectional, observational study involving a convenience sample size of young adult girls while attending the community pharmacies was carried out in Nicosia, Kyrenia, and Famagusta provinces in Northern Cyprus from January to June 2023. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Girne American University, Kyrenia, Northern Cyprus (Ref. no. 2020-21/004).

Sample sizeDuring the study, a three-stage sampling procedure based on population density (high, medium, and low) was obtained to ensure generalizability and reduce selection bias. The inclusion criteria included young adult girls between the ages of 18–26 years. Those who declined to participate or gave incomplete responses to survey questions were excluded. The estimated sample size was 379 participants using a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. A total of 405 participants were approached during this study. Nonetheless, 47 participants declined to participate and 58 participants were excluded due to missing data. As a result, a total of 300 respondents were enrolled in the study and finished the entire survey, obtaining a response rate of 89.6%.

Questionnaire designThe questionnaire was developed in English language by the researchers after significant and in-depth literature research in databases, such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and Scopus that was tailored to the current study's objectives. To enhance the linguistic precision of the questionnaire contents, the questionnaire was subjected to a process of forwarding and backward translation from English to Turkish language since the mother language of the population where the study was conducted is Turkish language. The face and content validity of the drafted questionnaire was validated and performed by two academic and medical specialists with extensive experience in survey-based research. Additionally, approximately 5% of the pre-survey tests underwent targeted sampling to clarify questions and determine whether the data provided reliable information. The feedback garnered from this pilot phase was applied to the questionnaire's clarity and comprehensibility. Data collected during this pilot project were excluded from the final statistical analysis of the data.

Through one-on-one interviews, the study's aim was elucidated to eligible participants who agreed to participate, and informed consent was obtained, ensuring voluntary participation with guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality. The questionnaire was administered to be completed by the respondents without an interviewer's assistance, which lasted approximately 15 min. The questionnaire's final version had 53 questions divided into five sections. The first section featured six items that included demographic information about the participants. The second section included sixteen items and assessed knowledge about BC potential risk factors. The third section included twelve items that assessed respondents' awareness of BC warning signs. The fourth section included ten items designed to assess knowledge of BC diagnosis and screening. The last part included nine items to assess the perceptions of BC treatment and outcomes.

Statistical analysisThe Statistical Program for Social Science Research, edition 23.0, and Microsoft Office Excel 2013 were used for analysing the data. The mean, standard deviation, and median range were used to express numerical variables, while number and percentage were used to express categorical variables. Positive knowledge and perception were given a score of 1, whereas negative knowledge and perception were given a score of 0. Individual statement knowledge, awareness, and perceptions scores were combined and calculated to give a participant's overall knowledge, awareness, and perceptions score. Negative knowledge, awareness, and perceptions were cut off at 50%, while positive knowledge, awareness, and perceptions were cut off at 50%. The independent Chi-square test was used to analyse the association between groups. The P-value at ≤0.05 was considered significant.

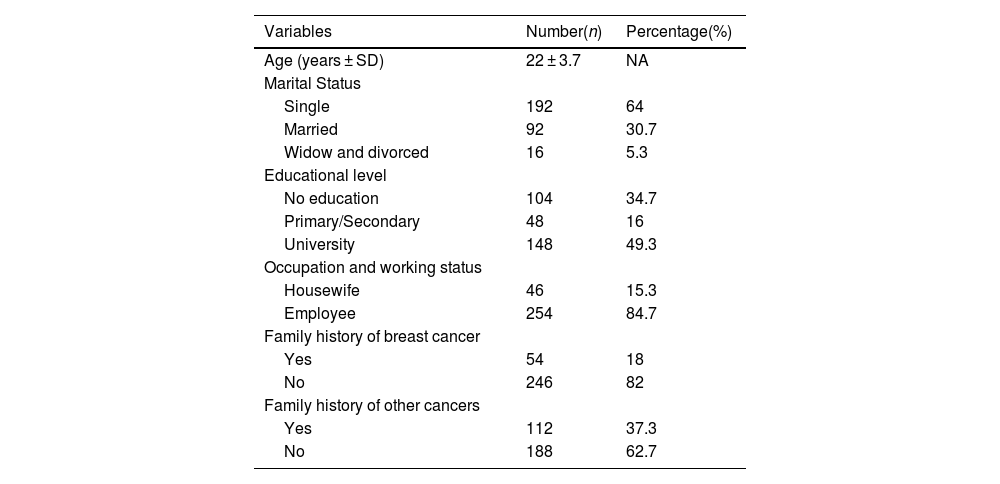

ResultsThe mean age of 22 ± 3.7 years, nearly half of the participants (64%), were single. Nearly half of the participants had a university education (49.3%). Most of the enrolled participants had neither a family history of BC (82%) nor a family history of other cancer types (62.7%), Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Variables | Number(n) | Percentage(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years ± SD) | 22 ± 3.7 | NA |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 192 | 64 |

| Married | 92 | 30.7 |

| Widow and divorced | 16 | 5.3 |

| Educational level | ||

| No education | 104 | 34.7 |

| Primary/Secondary | 48 | 16 |

| University | 148 | 49.3 |

| Occupation and working status | ||

| Housewife | 46 | 15.3 |

| Employee | 254 | 84.7 |

| Family history of breast cancer | ||

| Yes | 54 | 18 |

| No | 246 | 82 |

| Family history of other cancers | ||

| Yes | 112 | 37.3 |

| No | 188 | 62.7 |

Data present in number and percentage: n, %; NA: not available.

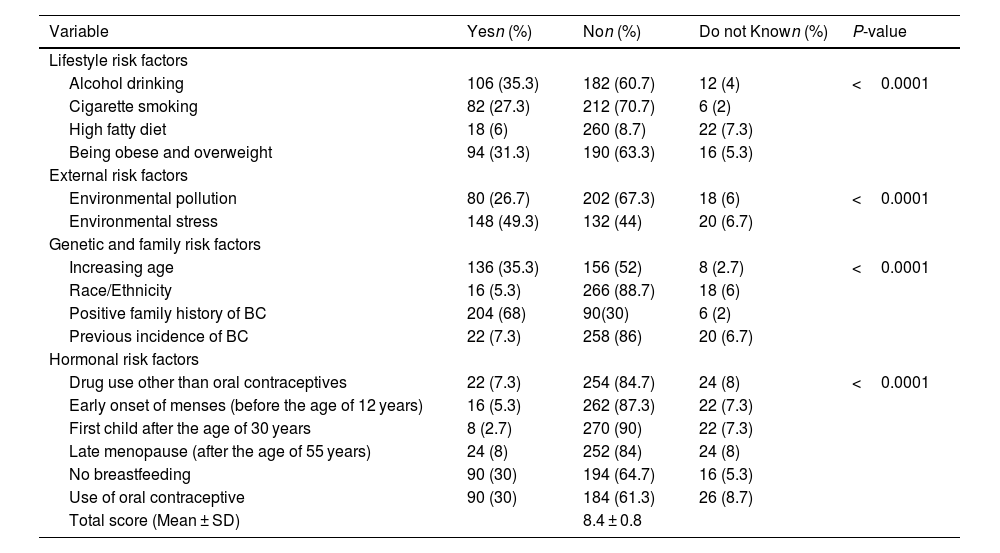

The assessment of knowledge of BC potential risk factors revealed overall poor knowledge (total score of 8.4 ± 0.8) and the proportion of young adult girls who reported overall correct answers was considerably low. Most of the participants had poor knowledge in many domains (P < 0.0001). This includes lifestyle and external risk factors, such as alcohol drinking (35.3%), cigarette smoking (27.3%), a high-fat diet (6%), being obese or overweight (31.3%), and environmental pollution (26.7%). A large proportion of study participants were also unable to recognise genetic and family risk factors, except for a positive family history of BC (68%). Furthermore, the study participants were poorly acknowledged about the overall hormonal risk factors, including drug use other than oral contraceptives (7.3%), early menstruation (5.3%), and late menopause (8%), as shown in Table 2.

Knowledge of potential risk factors of breast cancer among the participants.

| Variable | Yesn (%) | Non (%) | Do not Known (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle risk factors | ||||

| Alcohol drinking | 106 (35.3) | 182 (60.7) | 12 (4) | <0.0001 |

| Cigarette smoking | 82 (27.3) | 212 (70.7) | 6 (2) | |

| High fatty diet | 18 (6) | 260 (8.7) | 22 (7.3) | |

| Being obese and overweight | 94 (31.3) | 190 (63.3) | 16 (5.3) | |

| External risk factors | ||||

| Environmental pollution | 80 (26.7) | 202 (67.3) | 18 (6) | <0.0001 |

| Environmental stress | 148 (49.3) | 132 (44) | 20 (6.7) | |

| Genetic and family risk factors | ||||

| Increasing age | 136 (35.3) | 156 (52) | 8 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 16 (5.3) | 266 (88.7) | 18 (6) | |

| Positive family history of BC | 204 (68) | 90(30) | 6 (2) | |

| Previous incidence of BC | 22 (7.3) | 258 (86) | 20 (6.7) | |

| Hormonal risk factors | ||||

| Drug use other than oral contraceptives | 22 (7.3) | 254 (84.7) | 24 (8) | <0.0001 |

| Early onset of menses (before the age of 12 years) | 16 (5.3) | 262 (87.3) | 22 (7.3) | |

| First child after the age of 30 years | 8 (2.7) | 270 (90) | 22 (7.3) | |

| Late menopause (after the age of 55 years) | 24 (8) | 252 (84) | 24 (8) | |

| No breastfeeding | 90 (30) | 194 (64.7) | 16 (5.3) | |

| Use of oral contraceptive | 90 (30) | 184 (61.3) | 26 (8.7) | |

| Total score (Mean ± SD) | 8.4 ± 0.8 | |||

Data present in number and percentage: n, %.

Independent Chi-square; highly significant at P ≤ 0.05.

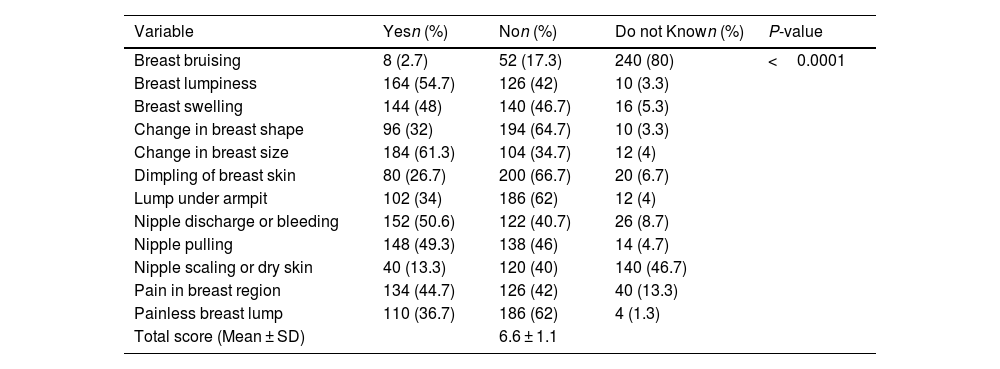

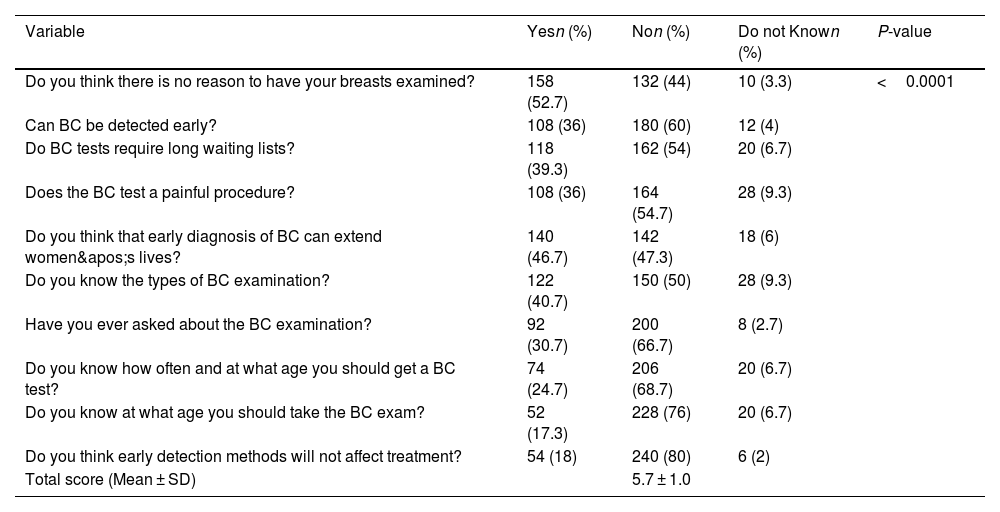

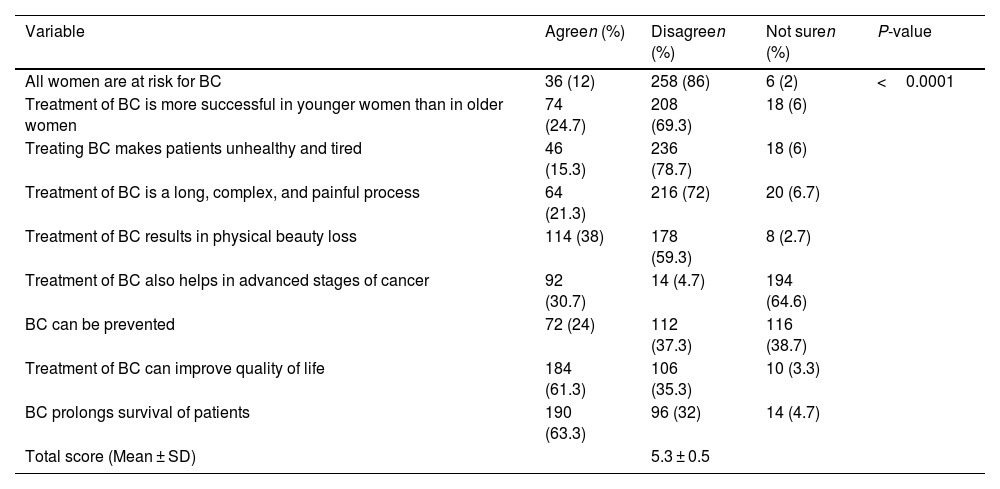

The study participants' responses also revealed overall poor awareness of the common warning signs of BC (P < 0.0001), with a total score of 6.6 ± 1.1. However, more than half of the respondents reported good knowledge and identified breast lumpiness (54.7%), change in breast size (61.3%), and nipple discharge (50.6%) as the most warning signs of BC, as shown in Table 3. Similarly, knowledge of BC diagnosis and screening was also poorly encountered among the study participants (P < 0.0001), with a total score of 5.7 ± 1.0. Nevertheless, the majority of participants expressed disagreement about “early detection methods will not affect treatment,” followed by an equal proportion (60%) about “BC tests requiring long waiting lists” and “BC tests being a painful procedure,” as shown in Table 4. Meanwhile, perceptions towards treatment and outcomes were not much different, as the majority of the study participants reported poor responses (P < 0.0001), with a total score of 5.3 ± 0.5. Surprisingly, most of the study participants had accurate perceptions in terms of improving patient quality of life (61.3%), and prolonging survival (63.3%), Table 5.

Awareness of warning signs of breast cancer among the participants.

| Variable | Yesn (%) | Non (%) | Do not Known (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast bruising | 8 (2.7) | 52 (17.3) | 240 (80) | <0.0001 |

| Breast lumpiness | 164 (54.7) | 126 (42) | 10 (3.3) | |

| Breast swelling | 144 (48) | 140 (46.7) | 16 (5.3) | |

| Change in breast shape | 96 (32) | 194 (64.7) | 10 (3.3) | |

| Change in breast size | 184 (61.3) | 104 (34.7) | 12 (4) | |

| Dimpling of breast skin | 80 (26.7) | 200 (66.7) | 20 (6.7) | |

| Lump under armpit | 102 (34) | 186 (62) | 12 (4) | |

| Nipple discharge or bleeding | 152 (50.6) | 122 (40.7) | 26 (8.7) | |

| Nipple pulling | 148 (49.3) | 138 (46) | 14 (4.7) | |

| Nipple scaling or dry skin | 40 (13.3) | 120 (40) | 140 (46.7) | |

| Pain in breast region | 134 (44.7) | 126 (42) | 40 (13.3) | |

| Painless breast lump | 110 (36.7) | 186 (62) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Total score (Mean ± SD) | 6.6 ± 1.1 |

Data present in number and percentage: n, %.

Independent Chi-square; highly significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Knowledge of breast cancer diagnosis and screening among the participants.

| Variable | Yesn (%) | Non (%) | Do not Known (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think there is no reason to have your breasts examined? | 158 (52.7) | 132 (44) | 10 (3.3) | <0.0001 |

| Can BC be detected early? | 108 (36) | 180 (60) | 12 (4) | |

| Do BC tests require long waiting lists? | 118 (39.3) | 162 (54) | 20 (6.7) | |

| Does the BC test a painful procedure? | 108 (36) | 164 (54.7) | 28 (9.3) | |

| Do you think that early diagnosis of BC can extend women's lives? | 140 (46.7) | 142 (47.3) | 18 (6) | |

| Do you know the types of BC examination? | 122 (40.7) | 150 (50) | 28 (9.3) | |

| Have you ever asked about the BC examination? | 92 (30.7) | 200 (66.7) | 8 (2.7) | |

| Do you know how often and at what age you should get a BC test? | 74 (24.7) | 206 (68.7) | 20 (6.7) | |

| Do you know at what age you should take the BC exam? | 52 (17.3) | 228 (76) | 20 (6.7) | |

| Do you think early detection methods will not affect treatment? | 54 (18) | 240 (80) | 6 (2) | |

| Total score (Mean ± SD) | 5.7 ± 1.0 |

Data present in number and percentage: n, %.

Independent Chi-square; highly significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Perceptions towards breast cancer treatment and outcomes among the participants.

| Variable | Agreen (%) | Disagreen (%) | Not suren (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All women are at risk for BC | 36 (12) | 258 (86) | 6 (2) | <0.0001 |

| Treatment of BC is more successful in younger women than in older women | 74 (24.7) | 208 (69.3) | 18 (6) | |

| Treating BC makes patients unhealthy and tired | 46 (15.3) | 236 (78.7) | 18 (6) | |

| Treatment of BC is a long, complex, and painful process | 64 (21.3) | 216 (72) | 20 (6.7) | |

| Treatment of BC results in physical beauty loss | 114 (38) | 178 (59.3) | 8 (2.7) | |

| Treatment of BC also helps in advanced stages of cancer | 92 (30.7) | 14 (4.7) | 194 (64.6) | |

| BC can be prevented | 72 (24) | 112 (37.3) | 116 (38.7) | |

| Treatment of BC can improve quality of life | 184 (61.3) | 106 (35.3) | 10 (3.3) | |

| BC prolongs survival of patients | 190 (63.3) | 96 (32) | 14 (4.7) | |

| Total score (Mean ± SD) | 5.3 ± 0.5 |

Data present in number and percentage: n, %.

Independent Chi-square; highly significant at P ≤ 0.05.

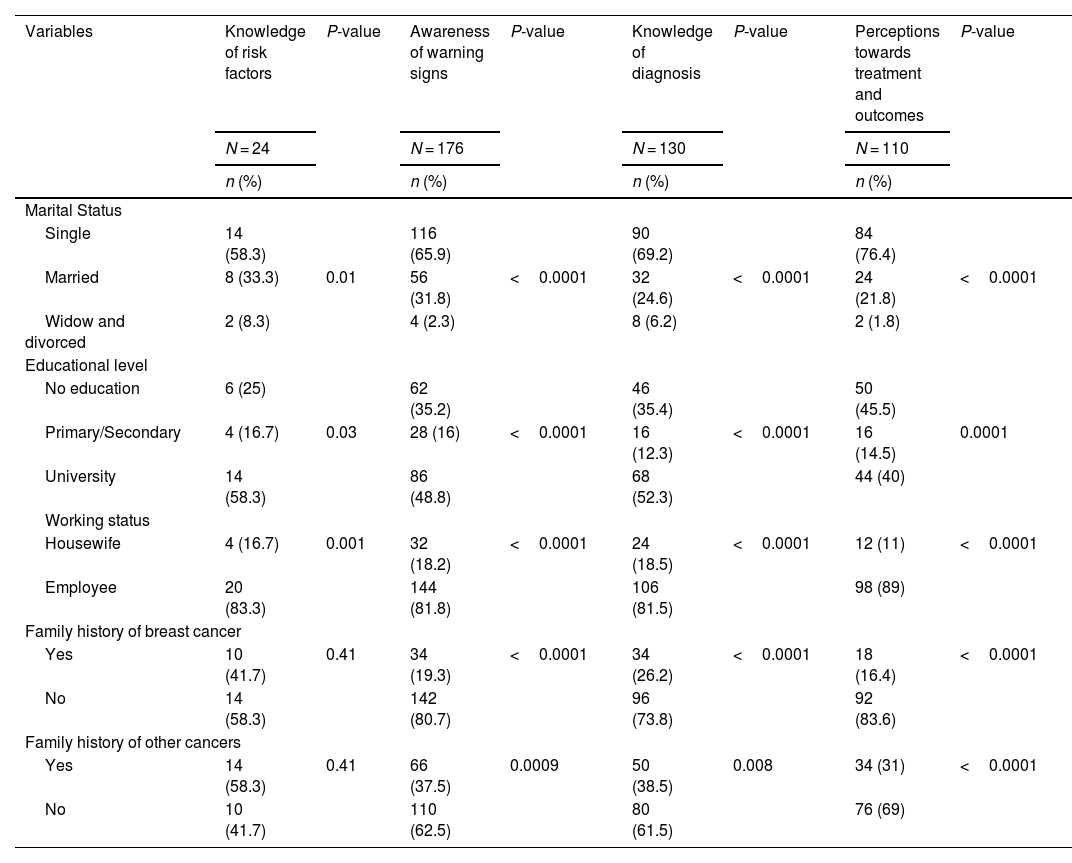

Knowledge of BC risk factors was found to be significantly associated with marital status (single), university education level (P = 0.03), and employment (P = 0.001). Similarly, awareness of warning signs, knowledge of BC diagnosis, and perceptions of treatment and outcomes were also found to be significantly associated with marital status (single), university education level, and employment, as shown in Table 6.

Association between demographic characteristics and Knowledge and perceptions of breast cancer among the participants.

| Variables | Knowledge of risk factors | P-value | Awareness of warning signs | P-value | Knowledge of diagnosis | P-value | Perceptions towards treatment and outcomes | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 24 | N = 176 | N = 130 | N = 110 | |||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Single | 14 (58.3) | 116 (65.9) | 90 (69.2) | 84 (76.4) | ||||

| Married | 8 (33.3) | 0.01 | 56 (31.8) | <0.0001 | 32 (24.6) | <0.0001 | 24 (21.8) | <0.0001 |

| Widow and divorced | 2 (8.3) | 4 (2.3) | 8 (6.2) | 2 (1.8) | ||||

| Educational level | ||||||||

| No education | 6 (25) | 62 (35.2) | 46 (35.4) | 50 (45.5) | ||||

| Primary/Secondary | 4 (16.7) | 0.03 | 28 (16) | <0.0001 | 16 (12.3) | <0.0001 | 16 (14.5) | 0.0001 |

| University | 14 (58.3) | 86 (48.8) | 68 (52.3) | 44 (40) | ||||

| Working status | ||||||||

| Housewife | 4 (16.7) | 0.001 | 32 (18.2) | <0.0001 | 24 (18.5) | <0.0001 | 12 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Employee | 20 (83.3) | 144 (81.8) | 106 (81.5) | 98 (89) | ||||

| Family history of breast cancer | ||||||||

| Yes | 10 (41.7) | 0.41 | 34 (19.3) | <0.0001 | 34 (26.2) | <0.0001 | 18 (16.4) | <0.0001 |

| No | 14 (58.3) | 142 (80.7) | 96 (73.8) | 92 (83.6) | ||||

| Family history of other cancers | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 (58.3) | 0.41 | 66 (37.5) | 0.0009 | 50 (38.5) | 0.008 | 34 (31) | <0.0001 |

| No | 10 (41.7) | 110 (62.5) | 80 (61.5) | 76 (69) | ||||

Data present in number and percentage: n, %.

Significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Knowledge and awareness play an important role in BC prevention, early detection, and optimal treatment. The current study showed that most participants had overall poor knowledge of BC potential risk factors and diagnostic methods which may contribute to delayed BC detection and early treatment. Our study showed that a very few proportion of the young adult girls were aware of many complex risk factors. However, alcohol consumption, environmental stress, ageing, and a family cancer history have been found to be potential predisposing risk factors for the BC development. The low level of knowledge about BC risk factors observed in this study is consistent with findings from other similar studies.18–20

It is worth noting that young adult girls at high risk of developing BC have insufficient awareness of warning signs. Recognising the signs is essential for early BC self-detection and treatment. Intervention should aim to improve awareness of BC signs, as delayed presentation remains a problem among women in developing countries. The results of this study showed that the proportion of participants who were aware of the warning signs of BC was relatively low, as they recognised breast lumpiness, change in breast size, and nipple discharge. In comparison to these results, a study conducted in Ethiopia has documented relatively good awareness about the BC warning signs.21

An increase in knowledge about BC screening leads to earlier diagnosis and intervention, increasing survival. Early diagnosis of cancer allows the disease to be detected before signs appear, increasing the likelihood and success of treatment, extending survival, and reducing cancer deaths.2 Our findings are discouraging, indicating a lack of information on BC screening. Personal fear, fear of consequences, and fear of hospitals are all possible reasons for not implementing BC screening.22,23 These results are comparable to a previous study by Ramakant et al.24 conducted to assess BC screening knowledge and practice, and the results were disappointing and not very encouraging. BC screening guidelines state that women should have mammograms every one to two years. Additionally, literature indicates that breast lumps are more likely to be self-discovered by women. Because many breast tumours are self-discovered by women, SBE can increase women's awareness of their breasts and thus make tumours easier to detect. Furthermore, SBE is recognised as a simple, inexpensive, non-invasive, and safe procedure that is not only accepted, inexpensive, and appropriate but also promotes active participation in preventive health care by women.25,26 Most of the study participants had accurate perceptions of BC management and its outcomes in terms of improving patient quality of life and prolonging survival. Moreover, they had a positive view of BC therapy is that it is not a painful, lengthy process. These results were inconsistent with a study conducted in Nigeria.27

Knowledge of BC risk factors, awareness of BC warning signs, knowledge of BC diagnosis, and perceptions of treatment and outcomes were found to be significantly associated with marital status, university education level, employment, neither having a family history of BC nor of other cancer types. It is well known that educated women are more likely to benefit from educational interventions concerning BC knowledge and awareness of the disease.28 While parity, age at first birth, and breastfeeding have been proven to have a substantial protective influence on the incidence of BC, lifelong single women typically have no experience with childbirth or breastfeeding. This may persuade single young adult girls to seek out more information and learn more about BC. On the other hand, employment typically requires human interaction and can therefore have beneficial effects. This is in line with other studies that revealed the positive effects of work on several health outcomes, such as general health, physical functioning, and mental health in healthy individuals, particularly women. These findings are in line with earlier studies.29–31 The results of this study suggest the need for tailored educational interventions using various channels and programmes such as social media, pamphlet distribution, mass media and appropriate counselling to improve knowledge, awareness and understanding of BC and its treatment. In addition, healthcare providers in hospitals and clinics should regularly provide appropriate counselling to improve BC knowledge, and brochures can be an effective tool in this regard. Healthcare providers should encourage young adult girls to undergo BC screening to reduce the incidence of the disease.

LimitationsTo our knowledge, this is the first conducted to assess knowledge of BC risk factors, the most common warning signs, diagnosis and screening, and perceptions about treatment outcomes among young women in Northern Cyprus. However, it is important to note the limitations of the current study. First, the survey enrolled only young adult girls and may not be representative of other women population in other parts of Northern Cyprus. Inconsistent understanding of the self-reported survey may have resulted in recall bias. With these limitations in mind, we recommend conducting further prospective cohort studies to further assess our knowledge and perception of BC.

ConclusionsThis study found that most young adult girls in Northern Cyprus had lower than expected knowledge of BC potential risk factors, awareness of warning signs, and knowledge of early cancer diagnosis and screening. The study population, on the other hand, had fairly positive perceptions of BC management and its outcomes in terms of improving patient quality of life and extending survival. The study highlights the need for an intensive acquisition of BC knowledge and awareness regarding all domains, particularly potential risk factors and early detection and screening at an early stage. Therefore, well-designed, and comprehensive educational programmes and additional future efforts should be put forth to promote behavioural changes through health education programmes that are recommended by healthcare providers and targeted for young adult girls.

Informed consentThe authors declare that they have obtained the consent of the patients for publication.

FundingThere is no funding support for this study.

There are no conflicts of interest.