Class II-1 can be the result of a retrognathic mandible, a prognathic maxillary or both. Nowadays, there are several ways for class II treatment: maxillary first bicuspid extractions that can also include the extraction of one lower incisor or the first or second mandibular bicuspids, depending the case, or even the extraction of the second maxillary bicuspids as well.

ObjectivesTo achieve canine class I, correct the midline discrepancy, the excessive overjet and to improve the patient’s aesthetics.

Case reportFemale patient of 32.6 years of age who had a previous orthodontic treatment with extractions of the first maxillary and mandibular bicuspids presents absence of the maxillary second bicuspid, generalized mild chronic periodontitis and previous mental foramen fracture with mentoplasty.

ConclusionsThe 2nd bicuspid extraction was the best alternative to avoid another surgery, with a significant change in the patient’s profile, improving her expectations and self-esteem.

La clase II-1 puede ser resultado de una mandíbula retrognata, de un maxilar prognato o de una combinación de ambas. Actualmente existen alternativas de tratamiento, como las extracciones de primeros premolares que en ocasiones se pueden acompañar de una extracción de incisivo central inferior o de segundos premolares inferiores, e incluso la extracción de los segundos premolares superiores, según sea el caso.

ObjetivosEstablecer clase I canina, corregir la línea media dental y el traslape horizontal, así como mejorar el perfil de los tejidos blandos.

Reporte del casoPaciente del sexo femenino de 32.6 años de edad. Presenta tratamiento ortodóncico previo con extracciones de primeros premolares superiores e inferiores, ausencia del segundo premolar superior izquierdo, periodontitis crónica leve generalizada y antecedentes de fractura en la sínfisis mentoniana con reconstrucción (mentoplastia).

ConclusionesLa extracción del segundo premolar maxilar fue la alternativa viable para evitar otra cirugía con un cambio significativo en el perfil, mejorando las expectativas y, especialmente, la autoestima de la paciente.

Class II divisioni is characterized because the buccal groove of the permanent lower molar is located distal to the mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first molar with protrusive incisors and increased overjet. It may be the result of a retrognathic mandible, a protrusive maxilla or a combination of both.1 Since time immemorial, biprotrusions were mentioned as an etiology for trying to correct the Class II through extractions thus improving facial aesthetics.2

Among the treatment options for class II-1 correction, the most frequent is the extraction of the four first premolars since they are located in the anterior segments of the dental arches which allows direct access to crowding and severe dentoalveolar protrusions correction. Another alternative is the removal of the first maxillary premolars and the second mandibular premolars. It is used in cases of dental and skeletal class II division 1 with severe upper anterior crowding or mild to moderate dentoalveolar protrusion and with a mandibular arch without many anterior problems. Extractions have an influence over the anterior lower facial height and they diminish vertical dimension.3 Through several studies it has been found that due to the light and controlled forces of current therapies, the retraction of six, eight and even ten teeth is possible when performing extractions.4 In some patients, the solution is orthognathic surgery, however, due to different causes this treatment is not viable and permanent bicuspid and/or molar extractions have to be performed as orthodontic camouflage.5,6

Case reportFemale patient of 32.6 years of age that attends the Orthodontics Clinic at the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Queretaro with the following chief complaint: «improve my smile because my teeth stick out too much» (Figure 1).

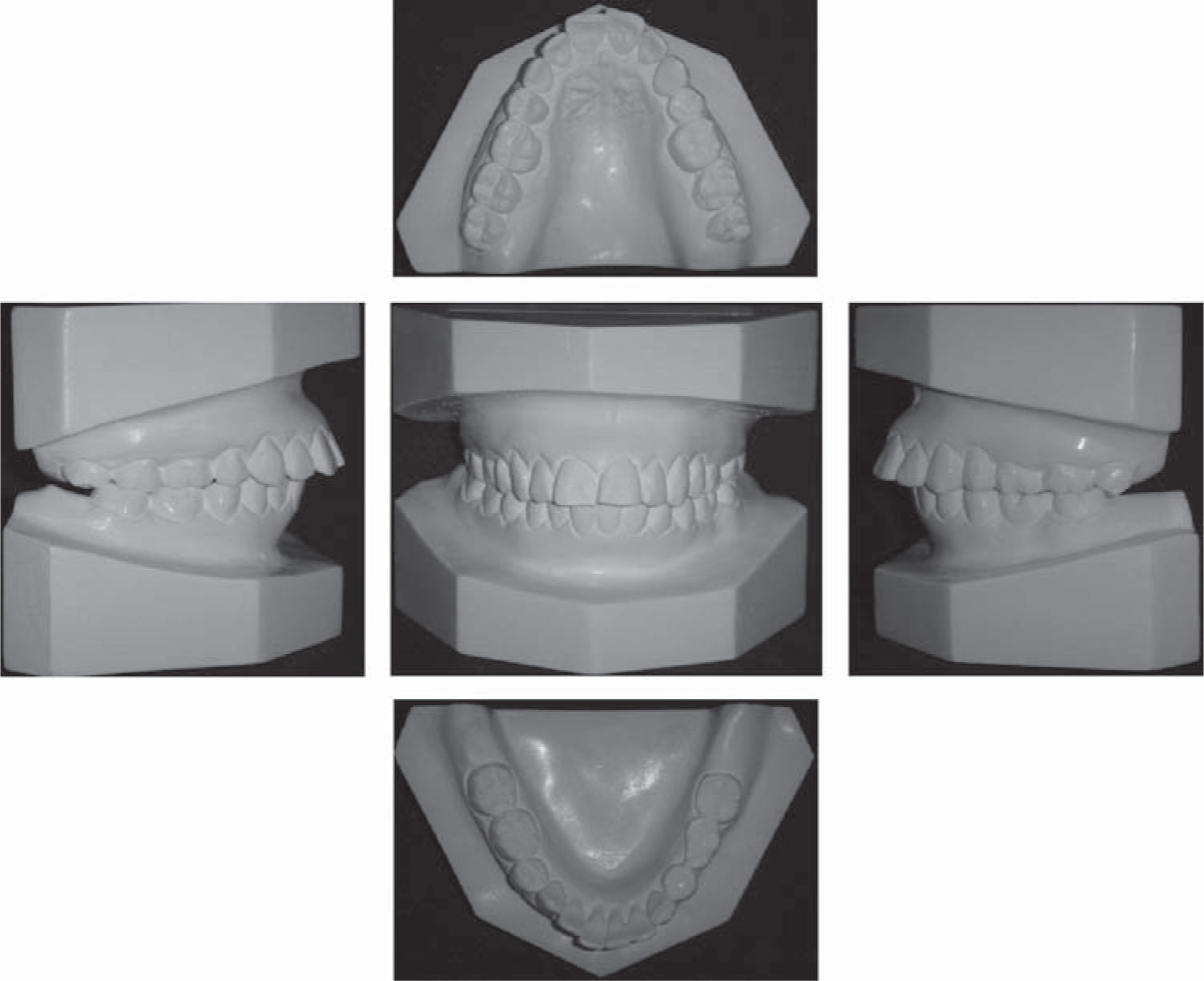

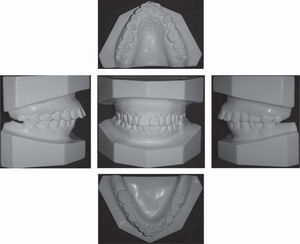

Clinical examinationThe patient presents a mesofacial pattern, straight profile with slight lower lip prochelia and lip incompetence. At the intraoral clinic examination, the patient presented two fixed prostheses of 3 metal ceramic units, one in the upper arch from canine to upper left first molar (pontic of second premolar); and in the lower dental arch, from first to second molar premolar on the left (a one unit pontic covering the second premolar and first molar); molar and canine class II on both sides, 7mm overjet, and 1mm overbite, upper dental midline deviation to the left and mild generalized chronic periodontitis (Figure 2).

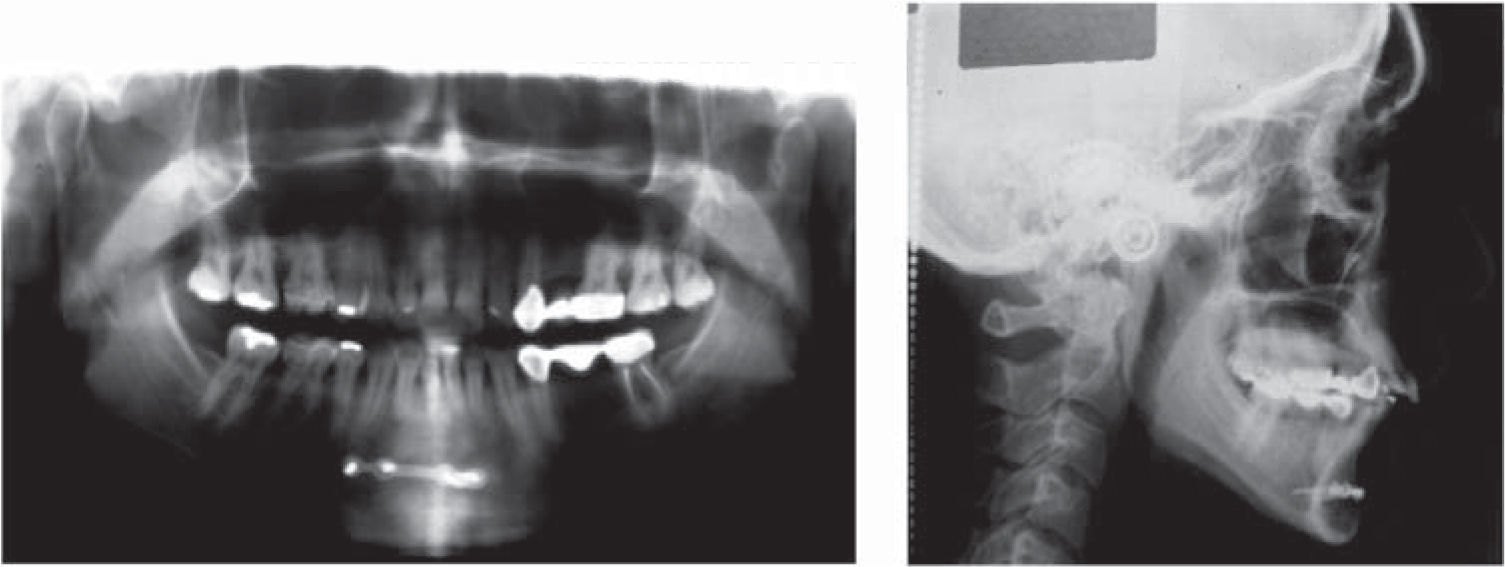

Radiographic examinationThe panoramic X-ray shows history of fracture in the symphysis menti with reconstruction (mentoplasty) and a previous orthodontic treatment with extractions of first premolars and lower second premolars, and absences of the upper left second premolar, lower left first molar and lower third molars.

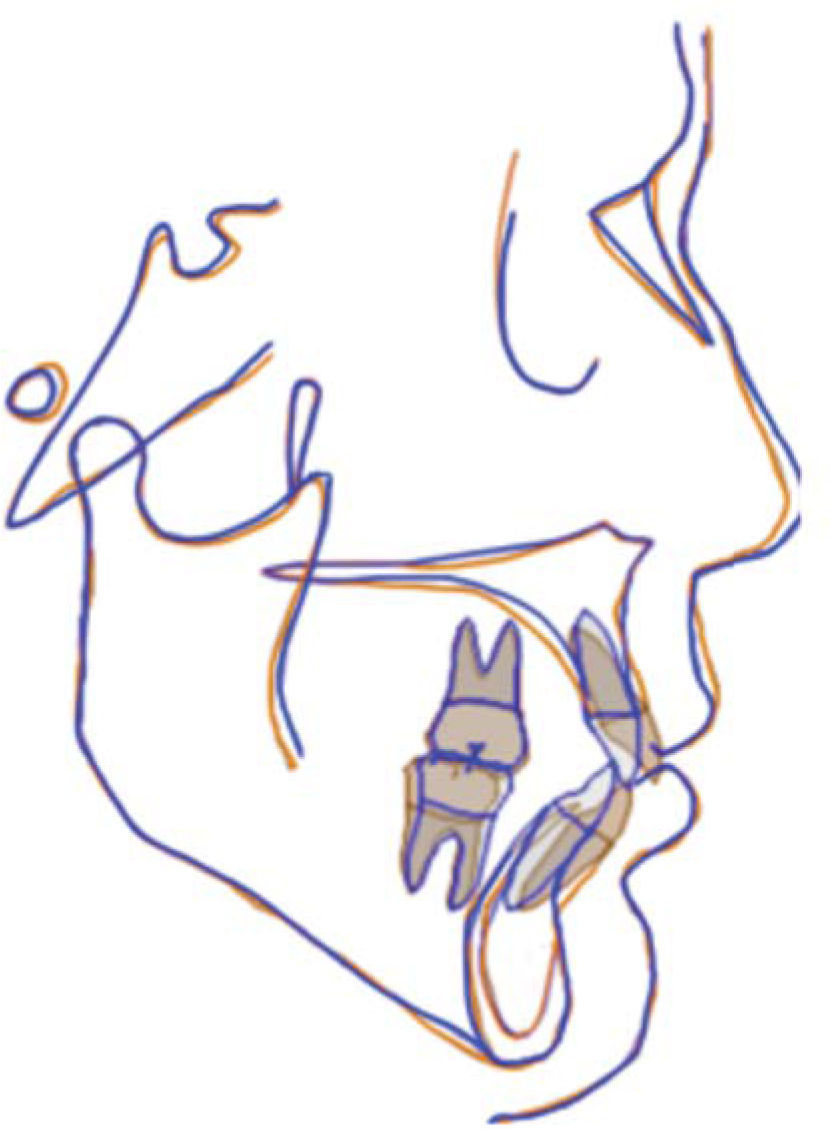

The cephalometric analysis revealed a class II-1 by retrognathism, neutral growth, upper and lower incisor proclination and dentoalveolar protrusion with a tendency towards open bite (Figure 3).

Diagnosis- •

Female patient of 32.6 years of age.

- •

Skeletal class I.

- •

Straight profile with lip incompetence.

- •

Neutral growth.

- •

Molar and canine class II.

- •

1mm overbite and 7mm overjet (Figure 4).

- •

Upper dental midline deviated to the left.

- •

Upper and lower incisor proclinaiton and protrusion.

- •

To achieve canine class I.

- •

To correct dental midline.

- •

To correct the overjet.

- •

To obtain lip competence.

- •

To improve the soft tissue profile.

- •

Segment the lower porcelain bridge respecting the porcelain crowns of the pillar teeth.

- •

Extraction of the upper right second bicuspid.

- •

Place Tip-Edge appliances.

The patient is referred to the Prosthetics Department for sectioning the porcelain bridge and eliminate the pontic of the upper left second premolar while respecting the porcelain crowns of the pillar teeth and to extract the upper right second premolar.

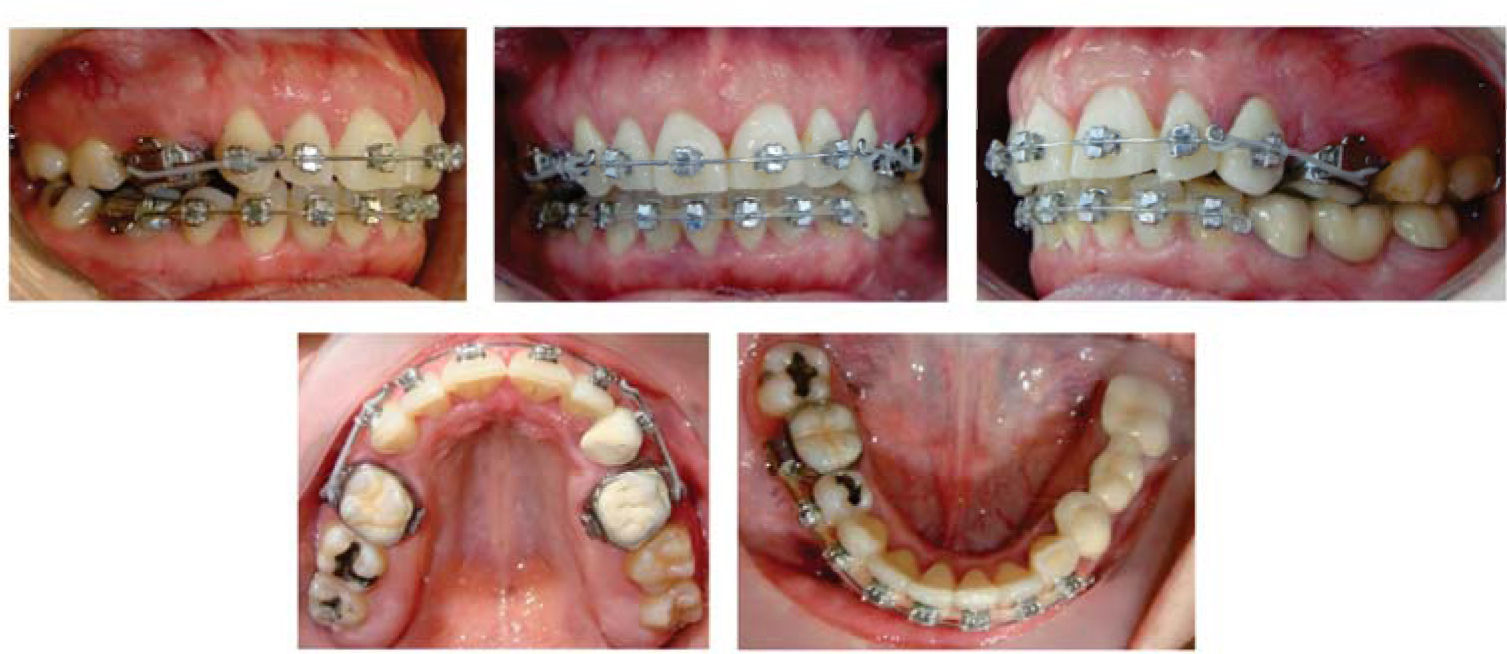

Phase I: Tip-Edge bracket and bands placement (except in the lower left second molar) with 0.016” NiTi upper and lower arches. Six weeks later, it was changed for a 0.016” Australian arch with an helix mesial to the canines and a tip-back bend 3mm mesial to the gingival tubes and with the use of 5/16” 2 oz Class II elastics.

Phase II: 0.020” Australian upper and lower arches were placed with a helix mesial to the canines and began with the use of E-links for space closure (Figure 5).

Phase III: 0.021”×0.025” archwires with Side Winder attachments for root uprighting and torque expression with the characteristics of a straight archwire system (Figure 6). Final detailing and settling of the occlusion. The appliances were removed and removable retainers were placed in the upper and lower arches.

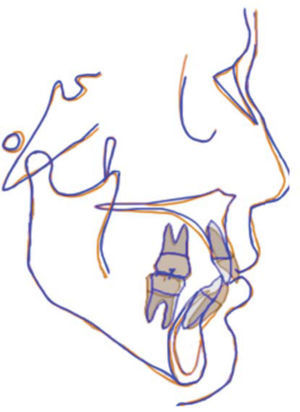

ResultsWith this treatment, a canine class I was achieved, the midline was centered, an adequate overjet and overbite were obtained along with functional guides, periodontal health and improvement of the patient’s profile by achieving lip competence (Figures 7 to 9).

DiscussionAccording to the studies of Raleigh and Kesling, the decision to perform extractions depends on the position of the lower incisor with the A-Po line or the denial of the patient for ortognathic surgery.7 Oynick mentions that in biprotrusive patients, the result perception improves when treated with extractions.8 Proffit mentions that the treatments can be performed with or without extractions when the aesthetics is affected, due to the great influence of inheritance in the etiology of the maloclussions.9

ConclusionsNowadays the need for extractions in patients with partial anodonthia might be controversial because of the existing surgical techniques or implants. When extractionsare required,the orthodontist must take very careful decisions in treatment planning and in biomechanics and be alert especially with molar control.

The case presented hereby presented was diagnosed as a surgical treatment and the decision was made to perform treatment with the extraction of the remnant premolar, moving the anterior teeth to a more harmonious position with the AP line and the facial profile, being a less radical alternative than surgery with a significant change in the profile and in doing so, improving the expectations and especially the self-esteem of the patient.