A cephalometric analysis of the upper airway in patients with cleft lip and palate sequelae who underwent orthognathic surgery was performed. The study aims to determine if changes in upper airway morphology occur. Study design: A retrospective, descriptive, open, comparative, and cross-sectional study with a sample of 28 patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae (UCLPS) was performed. The study sample consisted of 50% male and 50% female patients whose ages ranged between 16 and 29 years of age and averaged 19.32 years. Measurements were made on pre- and post-surgical lateral headfilms. A total of 672 cephalometric measurements were made. The study's findings indicate that changes in the upper airway after bone mobilization techniques in orthognathic surgery do exist. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 and was met on three of the assessed variables: upper pharynx (p = 0.001), bony pharynx dimension (p = .000), and nasopharyngeal depth (p = .000).

Se realizó un estudio cefalométrico de la vía aérea superior en pacientes con secuela de labio y paladar hendido unilateral (SLPHU) sometidos a procedimientos de cirugía ortognática, con la finalidad de conocer si existen cambios en la morfología de la vía aérea pre-y postquirúrgicos. El diseño del estudio fue observacional descriptivo, abierto, comparativo, retrospectivo y transversal en una muestra de 28 pacientes con SLPHU, correspondiendo el 50% al género masculino y 50% al femenino. El rango de edad fue de 16 a 29 años con un promedio de 19.32 años. Las mediciones fueron realizadas en radiografías laterales de cráneo pre y post quirúrgicas, con un total de 672 trazos cefalométricos. Los hallazgos encontrados en el presente estudio muestran que sí existen cambios en la vía aérea superior después de los procedimientos de movilización ósea con cirugía ortognática. Se observó una diferencia estadísticamente significativa (p < 0.05) en tres de las variables medidas: faringe superior (p = 0.001), dimensión faríngea ósea (p = .000) y profundidad nasofaríngea (p = .000).

Cleft lip and palate (CLP) is an oral-maxillary congenital malformation. The world literature accepts that the incidence of cleft lip and palate is 0.8 to 1.6 cases per 1,000 births.1–6 Some authors reported that variations are due to different ethnic and geographic conditions.7

In Mexico, according to Armendares and Lisker,8 1.39 cases per 1,000 live births are reported, which is consistent with international reports.9,10 These data identify that there are 9.6 new cases per day which in Mexico represent 3,521 new cases a year; that figure is considered as the CLP incidence at national level. Since it is a congenital pathology, its prevalence does not increase and in number it is equal to the incidence minus the mortality per year which is gradually decreasing.

Naso-labial-alveolar-palatal fissures are craniofacial malformations caused by embryologic defects in the formation of the face between the fourth and twelfth week of pregnancy. They present characteristic symptoms that affect the respiratory, swallowing, articular, language, hearing, and voice mechanisms with effects not only at an aesthetic level, but also at a functional level. Due to the complexity of the deformity, patients with maxillofacial clefts require a multidisciplinary approach for their rehabilitation.

Comprehensive treatment of this anomaly requires for every case an average of 3.5 surgical events during the patient's lifetime. Every programmed surgical intervention is considered a surgical event which may include two or three procedures during the same act.11

The head is the body's region where a numerous amount of functions take place such as breathing, deglutition, audition, vision, etc. Each one of these is executed by what Moss named a functional cranial component.

PHARYNGEAL REGIONSHuman beings have a unique configuration of the pharynx in which the larynx is located below the oral cavity so that the trachea and esophagus share a common path. The low position of the larynx (voice box) provides the physiological basis for speech in humans and creates a double-tube supralaryngeal vocal tract where the length of the horizontal tube (from the lips to the rear wall of the pharynx) and the vertical pipe (from the vocal cords to the soft palate) have an approximate ratio of 1:1.12

The process of growth and development of the craniofacial complex expresses the potential of each of its constituent elements when in harmony of form, speed and direction; this condition, when unfulfi lled, causes disharmony and discrepancies in size and position of the structures involved in each of the planes: horizontal, vertical, sagittal and transverse.

The embryological origin of the facial structures is bilateral and because of the inherent differences in the quality and time of sequential presentation, its characteristics and genetic potential can be influenced and modified. Also, when the anatomical and functional limits of compensation are surpassed by injuries in the functional matrix or in the growth centers, dysfunctions may occur that can lead to a degree of invalidity with an inherent potential of deterioration. These compensations or restrictions may have a direct or an indirect influence in places near or away from the originally affected site as is the case of the cleft lip and palate and other craniofacial anomalies such as fissures, agenesis and craniosynostosis.

CLEFT LIP AND PALATE SEQUELAEAll patients with cleft lip and/or cleft palate may have various structural and functional consequences attributable to characteristics of the initial deformity, facial development and surgical interventions and in addition, to complications due to different causes. One of the most common sequelae in this kind of patients is the retrusion of the middle facial third which is caused by factors of both the cleft lip and the cleft palate and in a secondary way, by factors pertaining to the congenital anomaly and by the multiple surgeries to which these patients are submitted.13 All of the above cause dental malocclusion and a disproportion between facial structures that may be corrected via orthodontics and orthopedics, as long as the growth process continues, by individually guiding teeth into modifying their position and thus, maxillary and mandibular growth regionally. Once the skeleton has matured in terms of ossification, the surgical procedure becomes necessary for the same purposes. This is why the majority of orthognathic surgical procedures are programmed for the stage in which growth has ceased.14

A significant number of treated patients become adults who have problems related to labial-palatal fissures.15 Because of its impact on language, these fissures are preferentially corrected at early stages of life and as a result of this intervention maxillary growth is affected and requires a more aggressive treatment in up to 25% of the cases in patients where orthodontic-orthopedic treatment is not sufficient for correction.16

Orthognathic surgery involves the manipulation of elements of the facial skeleton in order to restore the anatomical and functional proportion in patients with dentofacial anomalies. Elements of the facial skeleton may be repositioned, redefining the face through a variety of well-established osteotomies, which include LeFort I, II and III osteotomies, segmental maxillary osteotomy, mandibular ramus sagittal osteotomy, vertical ramus osteotomy, inverted L osteotomy, segmental mandibular body osteotomy and mandibular symphysis osteotomy. However, the majority of maxillofacial deformities are handled with three basic osteotomies:

- 1)

Middle third → LeFort I.

- 2)

Lower Third → Sagittal in mandibular ramus.

- 3)

Horizontal osteotomy in the symphysis of the chin.

Any orthognathic surgery to advance or retract the mandible will modify the gravity center of the head and the spatial relationships of the suprahyoid cranial structures which are associated with changes in head posture.

One of the characteristics of the hyoid bone is its mobility which has been suggested as a physiological response to the functional requirements of swallowing, breathing and fono-articulation. The hyoid bone also plays a role in keeping the airway open by causing tension to the cervical fascia, decreasing the soft tissue internal suction and preventing the compression of large blood vessels, and lungs in the apical part.

In the lateral headfilm, the airway is seen as a radiolucent strip that begins at the posterior choanae and is directed downwards and backwards following the curvature of the upper floor of the nostrils. There is no numerical or proportional relationship to determine the width of this space; instead it is based on a bi-dimensional radiographic assessment. The determination of the degree of blockage of the upper airway can be done on three regions of the craneocervical relationship.

- A.

Epipharynx.

- B.

Retrofaringe.

- C.

Hypopharynx.

The aim of this study was to determine by means of cephalometric studies the changes that occur in the upper airway in patients with sequelae of unilateral cleft lip and palate treated with orthodontic-surgical procedures. No study has been found that accurately measures cephalometric changes in the upper airway in patients with cleft lip-palate sequelae treated with this kind of procedures. Pre-surgical orthodontic preparation must include the prediction of the expected post-surgical morphological and functional changes in the airway.

BACKGROUNDLinder-Aronson (1974) was one of the first researchers to mention the possible influence of the skeletal structure size over naso-pharyngeal dysfunction; he suggested the use of Basion, Sella and Posterior Nasal Spine (Ba-S-PNS), an angle that remains stable since two years of age, for the sagittal assessment of the nasopharynx in the lateral headfilm.17,18

Ross in 1987 published the results of a series of 528 patients with cleft lip and palate surgically treated in 15 institutions around the world. The results showed that 25% of the patients developed maxillary hypoplasia that did not respond only to orthodontic procedures.

Sollow (1967), Tallgren (1977) and Posnick (1978) demonstrated that there are statistical correlations between the predominant mode of breathing, head posture and some facial features.

Harvold,19 in 1973 conducted a study in experimental animals and confirmed the relationship between oral breathing and occlusal disorders. Miloslavich, Rocabado and Tapia, Ricketts, Tourne, Handelman and Osborne related the adjacent skeletal structures to the type of breathing, asserting that nasopharyngeal structures increase the possibility of type of breathing and/or facial morphology alteration.

Achilleos, Krogstad and Lyberg in 2000 determined that after prognathism correction by means of a surgical procedure with mandibular retrusion, the tongue base and the soft palate raise and as a result, the upper airwayis reduced.20

Wenzel (1989), Katakura (1993) and Hochbahn, (1996), showed a significant decrease in sagittal pharyngeal dimensions and an increase in the extension of the head following a mandibular retrusion.14,15,21

Li et al., in the year 2002 reported a series of twelve patients in whom the pre and postoperative condition of the upper airway was assessed. The patients suffered from Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and had maxillo-mandibular surgical advancements performed. When comparing the radiographic and endoscopic assessments, it was found that both study methods adequately evaluated the changes produced in the airway.16

MATERIAL AND METHODSA total of 56 cephalograms corresponding to 28 files of patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae (n = 28) who underwent orthognathic surgery procedures were selected. They were all treated in the Stomatology-Orthodontics Division of the General Hospital «Dr. Manuel Gea González». Of the total number of patients, 24 cases (85.7%) had a Le Fort I surgery for maxillary advancement and 4 cases (14.3%) were submitted to a combined surgery of maxillary advancement and mandibular retroposition.

Every file that was found to be complete with pre- and postsurgical headfilms was included; the sample consisted in 14 male patients (50%) and 14 female (50%), with an age range of 16 to 29 years and a mean of 19.32 years. 672 cephalometric measurements were obtained for this study.

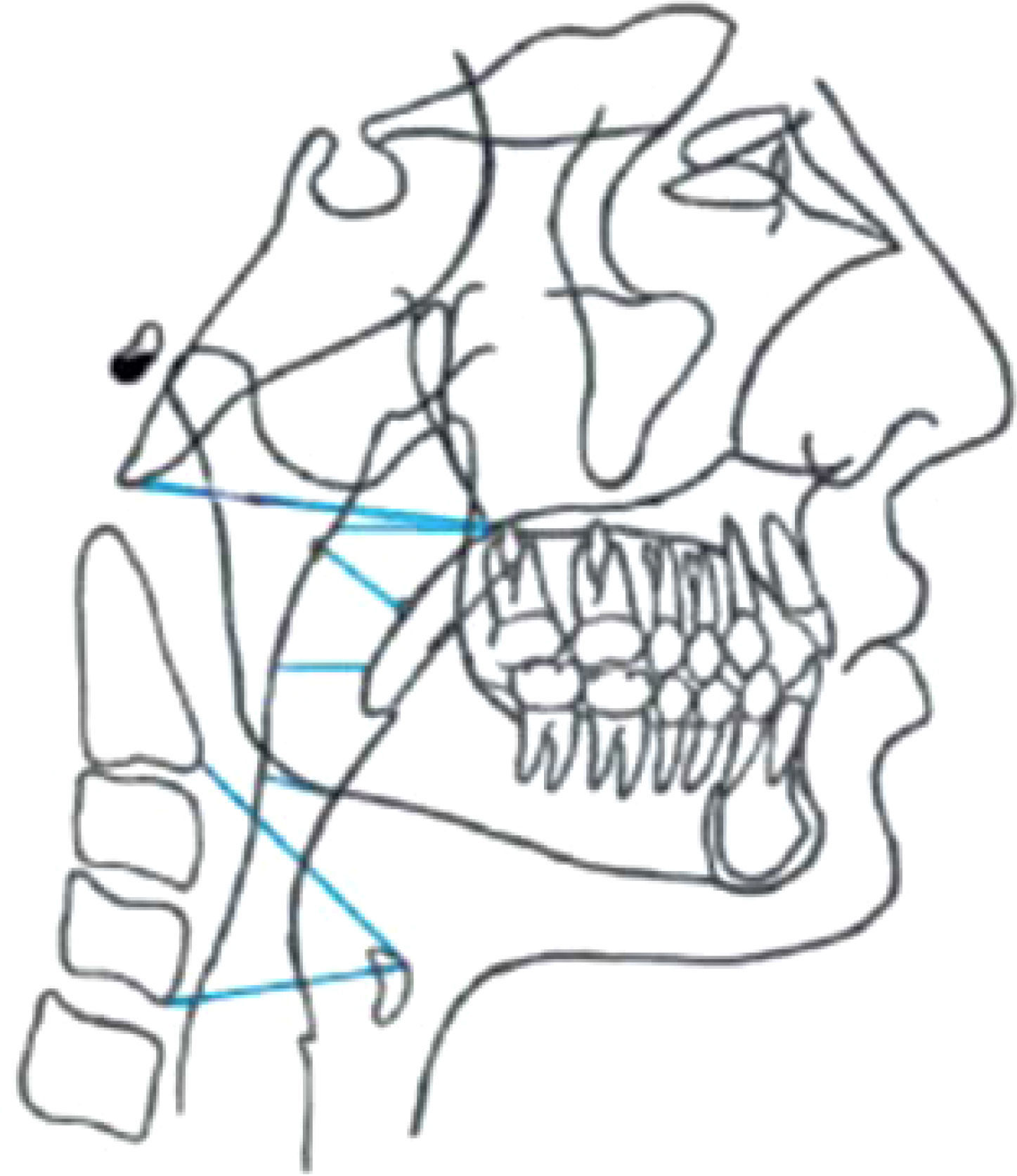

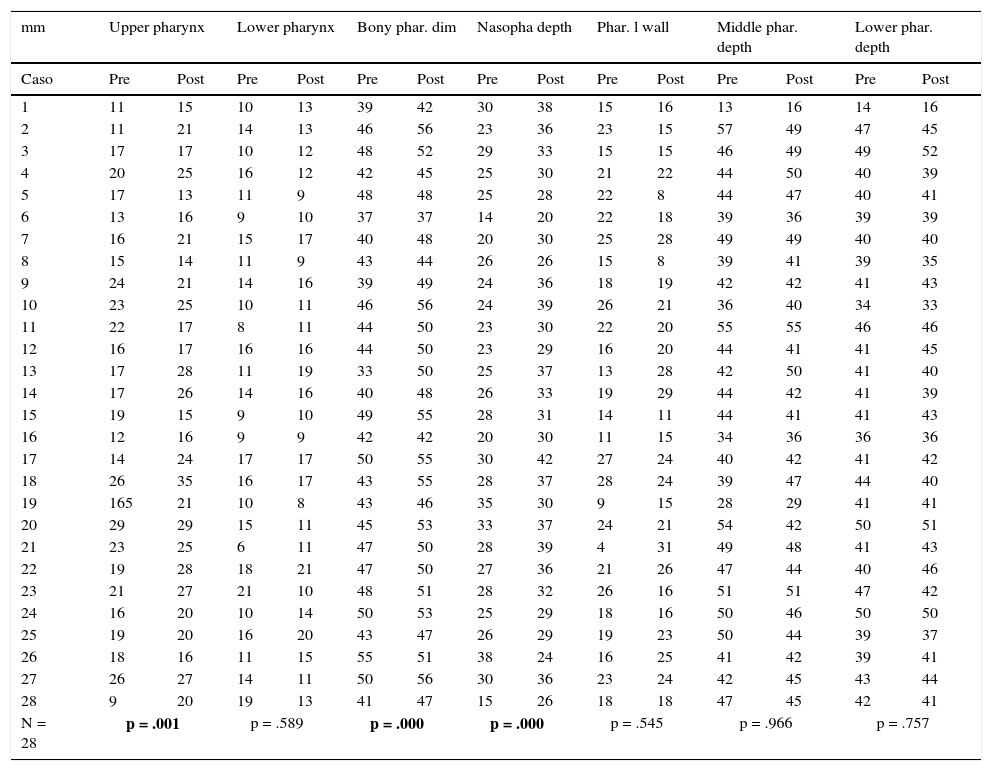

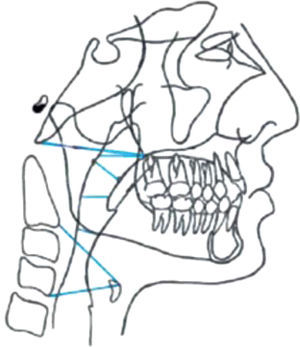

PROCEDURE DESCRIPTIONThe main investigator, who was previously calibrated, performed the McNamara and Athanasiou's cephalometric tracings in the pre and post-surgical treatment cephalograms, considering as variables the following measurements: upper pharynx, lower pharynx, bony pharynx dimension, nasopharyngeal depth, pharyngeal wall, middle pharyngeal depth and lower pharyngeal depth (Figure 1). The obtained values were recorded in the data collection sheet and were compared in order to determine post-surgical treatment changes in the upper airway. The obtained results were analyzed with the paired «T» statistical test.

STATISTICAL ANALYSISFor this study's validation, descriptive statistics, central tendency and dispersion measurements, percentages and ratios were used as well as the paired «T» test for comparative samples with SPSS v. 17. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTSFrom the sample of patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae, pre and post-surgical cephalometric changes in the upper airway were analyzed and compared using the paired «T» test. A statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed in three of the measured variables: upper pharynx (p = 0.001), bony pharynx dimension (p = .000) and nasopharyngeal depth (p = .000). The rest of the assessed variables did not show a different behavior within groups, therefore, no significant changes were found according to the statistical analysis (Table I). The types of surgical procedures found in the sample corresponded to 24 cases (85.7%) with Le Fort I surgery for maxillary advancement and 4 patients (14.3%) in whom a combined surgery of maxillary advancement and mandibular retrusion was performed.

Pre and post-surgical measurements with their statistical significance value.

| mm | Upper pharynx | Lower pharynx | Bony phar. dim | Nasopha depth | Phar. l wall | Middle phar. depth | Lower phar. depth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caso | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post |

| 1 | 11 | 15 | 10 | 13 | 39 | 42 | 30 | 38 | 15 | 16 | 13 | 16 | 14 | 16 |

| 2 | 11 | 21 | 14 | 13 | 46 | 56 | 23 | 36 | 23 | 15 | 57 | 49 | 47 | 45 |

| 3 | 17 | 17 | 10 | 12 | 48 | 52 | 29 | 33 | 15 | 15 | 46 | 49 | 49 | 52 |

| 4 | 20 | 25 | 16 | 12 | 42 | 45 | 25 | 30 | 21 | 22 | 44 | 50 | 40 | 39 |

| 5 | 17 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 48 | 48 | 25 | 28 | 22 | 8 | 44 | 47 | 40 | 41 |

| 6 | 13 | 16 | 9 | 10 | 37 | 37 | 14 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 39 | 36 | 39 | 39 |

| 7 | 16 | 21 | 15 | 17 | 40 | 48 | 20 | 30 | 25 | 28 | 49 | 49 | 40 | 40 |

| 8 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 43 | 44 | 26 | 26 | 15 | 8 | 39 | 41 | 39 | 35 |

| 9 | 24 | 21 | 14 | 16 | 39 | 49 | 24 | 36 | 18 | 19 | 42 | 42 | 41 | 43 |

| 10 | 23 | 25 | 10 | 11 | 46 | 56 | 24 | 39 | 26 | 21 | 36 | 40 | 34 | 33 |

| 11 | 22 | 17 | 8 | 11 | 44 | 50 | 23 | 30 | 22 | 20 | 55 | 55 | 46 | 46 |

| 12 | 16 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 44 | 50 | 23 | 29 | 16 | 20 | 44 | 41 | 41 | 45 |

| 13 | 17 | 28 | 11 | 19 | 33 | 50 | 25 | 37 | 13 | 28 | 42 | 50 | 41 | 40 |

| 14 | 17 | 26 | 14 | 16 | 40 | 48 | 26 | 33 | 19 | 29 | 44 | 42 | 41 | 39 |

| 15 | 19 | 15 | 9 | 10 | 49 | 55 | 28 | 31 | 14 | 11 | 44 | 41 | 41 | 43 |

| 16 | 12 | 16 | 9 | 9 | 42 | 42 | 20 | 30 | 11 | 15 | 34 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| 17 | 14 | 24 | 17 | 17 | 50 | 55 | 30 | 42 | 27 | 24 | 40 | 42 | 41 | 42 |

| 18 | 26 | 35 | 16 | 17 | 43 | 55 | 28 | 37 | 28 | 24 | 39 | 47 | 44 | 40 |

| 19 | 165 | 21 | 10 | 8 | 43 | 46 | 35 | 30 | 9 | 15 | 28 | 29 | 41 | 41 |

| 20 | 29 | 29 | 15 | 11 | 45 | 53 | 33 | 37 | 24 | 21 | 54 | 42 | 50 | 51 |

| 21 | 23 | 25 | 6 | 11 | 47 | 50 | 28 | 39 | 4 | 31 | 49 | 48 | 41 | 43 |

| 22 | 19 | 28 | 18 | 21 | 47 | 50 | 27 | 36 | 21 | 26 | 47 | 44 | 40 | 46 |

| 23 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 10 | 48 | 51 | 28 | 32 | 26 | 16 | 51 | 51 | 47 | 42 |

| 24 | 16 | 20 | 10 | 14 | 50 | 53 | 25 | 29 | 18 | 16 | 50 | 46 | 50 | 50 |

| 25 | 19 | 20 | 16 | 20 | 43 | 47 | 26 | 29 | 19 | 23 | 50 | 44 | 39 | 37 |

| 26 | 18 | 16 | 11 | 15 | 55 | 51 | 38 | 24 | 16 | 25 | 41 | 42 | 39 | 41 |

| 27 | 26 | 27 | 14 | 11 | 50 | 56 | 30 | 36 | 23 | 24 | 42 | 45 | 43 | 44 |

| 28 | 9 | 20 | 19 | 13 | 41 | 47 | 15 | 26 | 18 | 18 | 47 | 45 | 42 | 41 |

| N = 28 | p = .001 | p = .589 | p = .000 | p = .000 | p = .545 | p = .966 | p = .757 | |||||||

In accordance with the literature and when performing a comparison between the background information and the results obtained in the present study we agree that bone mobilization of the craniofacial complex generates changes in the upper airway morphology in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae who did not respond to orthodontic treatment only and had the need to resort to orthognathic surgery procedures.

Due to the modality adopted by our study and because of the variety of surgical procedures, it is not possible to determine the positive or negative impact of these changes since the patient's clinical assessment was not taken into consideration.

CONCLUSIONSThere are changes in upper airway morphology in patients with unilateral cleft-lip and palate who underwent orthognathic surgical procedures.

In the present study three statistically significant variables were obtained for such changes which show a different behavior within the study group. Therefore, it is suggested to conduct further prospective controlled clinical trials with specific variables such as age where unified criteria for surgical procedures or radiographic timing are determined. It would be necessary to include technological advancements by means of cone-beam for this assessment taking into consideration the variables presented in this study as statistically significant.

This article can be read in its full version in the following page: http://www.medigraphic.com/ortodoncia