Empathy has cognitive and emotional dimensions that healthcare professionals need to develop. Empathy also influences the learning environment and student outcomes in simulation-based education. This study explored the empathy profiles of simulation instructors and analyzed how cognitive and affective dimensions correlate with demographic characteristics.

MethodsQuantitative, observational, cross-sectional study conducted with 36 novice simulation instructors. Empathy was evaluated using the Test of Cognitive and Affective Empathy, which assesses four dimensions of empathy: Perspective Adoption (PA), Emotional Understanding (EU), Empathic Distress (ED), and Empathic Joy (EJ). Statistical analysis was conducted using Kruskal-Wallis and Spearman's Rho tests in JASP (v0.19.1).

ResultsMost participants were women (83.33%), aged 30–34 years (41.67%), and held a master's degree (80.56%). One-third of the participants (33%) scored =94th percentile on total empathy. PA and EJ scores were consistently high, while EU and ED showed greater variability. Gender differences were significant, with men scoring higher in total empathy, EU, and ED (p<0.05). Structured training correlated with higher ED; lack of conference attendance correlated with higher EU. There were no associations between empathy scores and years of experience or academic qualifications.

ConclusionsSimulation instructors in this study exhibited high cognitive empathy, with variable levels of affective empathy. Empathy profiling can be an integral part of tailored instructor training that strikes a balance between emotional responsiveness and psychological safety. These results highlight the importance of including strategies to improve emotional resilience and promote effective educator-student interactions in simulation faculty development programs.

La empatía tiene dimensiones cognitivas y emocionales que los profesionales de la salud deben desarrollar. Además, la empatía influye en el entorno de aprendizaje y en los resultados de los estudiantes en la educación basada en la simulación. Este estudio exploró los perfiles de empatía de los instructores de simulación y analizó cómo las dimensiones cognitivas y afectivas se correlacionan con las características demográficas.

MétodosEstudio cuantitativo, observacional y transversal realizado con 36 instructores de simulación novatos. La empatía se evaluó mediante la Prueba de Empatía Cognitiva y Afectiva, que evalúa cuatro dimensiones de la empatía: Adopción de Perspectiva (PA), Comprensión Emocional (EU), Angustia Empática (ED) y Alegría Empática (EJ). El análisis estadístico se realizó utilizando las pruebas de Kruskal-Wallis y Spearman's Rho en JASP (v0.19.1).

ResultadosLa mayoría de los participantes eran mujeres (83,33%), tenían entre 30 y 34 años (41,67%) y poseían un título de máster (80,56%). Un tercio de los participantes (33%) obtuvo una puntuación =94 en el percentil de empatía total. Las puntuaciones de AP y AE fueron consistentemente altas, mientras que las de UE y DA mostraron una mayor variabilidad. Las diferencias de género fueron significativas, ya que los hombres obtuvieron puntuaciones más altas en empatía total, EU y ED (p<0,05). La formación estructurada se correlacionó con una mayor ED; la falta de asistencia a conferencias se correlacionó con una mayor EU. No se observaron asociaciones entre las puntuaciones de empatía y los años de experiencia o las titulaciones académicas.

ConclusionesLos instructores de simulación de este estudio mostraron un alto nivel de empatía cognitiva, con niveles variables de empatía afectiva. La elaboración de perfiles de empatía puede ser una parte integral de la formación personalizada de los instructores, que permite lograr un equilibrio entre la capacidad de respuesta emocional y la seguridad psicológica. Estos resultados ponen de relieve la importancia de incluir estrategias para mejorar la resiliencia emocional y promover interacciones eficaces entre educadores y estudiantes en los programas de desarrollo del profesorado de simulación.

Empathy primarily involves understanding or feeling others’ emotions or experiences. Thus, empathy has cognitive and emotional dimensions that healthcare professionals need to develop1.

Active learning methodologies can improve empathic learning outcomes in students2. Simulation is one of the most effective strategies for developing emotional competencies, including empathy, in nursing students3. Specific areas where simulation can be effectively utilized for student training include empathy toward older adults4,5, pain and care management in burn patients6, and difficult communication at the end of life7. A meta-ethnography by Krishnasamy et al.8 identified four elements that influence the development and expression of empathy and compassion in medical education: seeing the patient as a person, appreciating the conceptual foundations of empathy and compassion, navigating the training environment, and being guided by professional ideals. Simulation-based education offers an opportunity to engage with these elements in a structured and reflective manner, reinforcing that empathy is a target of clinical performance and a central component of the educational environment.

Empathy has been assessed using multiple instruments. Some consider empathy a cognitive attribute, while others recognize that it has cognitive and affective dimensions9. Some studies have described positive associations between affective empathy and depression, anxiety, and burnout, whereas cognitive empathy presents the opposite trend1,9. These findings support the importance of awareness of empathy dimensions in educational contexts, including the training of simulation instructors.

The Test of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (TECA) assesses the emotional perspective of health professionals and instructors. It differentiates four dimensions into two facets: cognitive and affective. It employs a criterion to classify empathy profiles, identifying extreme profiles that may impact the instructor's performance10.

While empathy is necessary to create a safe space for learning in simulation11,12 and simulation-based education fosters students’ empathy3, the profiles of empathy's affective and cognitive dimensions in simulation instructors remain understudied.

Knowing the teachers’ empathy profiles is an initial step in understanding empathy's effect on creating a safe simulation environment and promoting student learning outcomes. It could be helpful to consider supporting programs for teachers’ well-being.

All of this need motivates the present research, which aims to analyze the empathic capacity profile of undergraduate simulation instructors and the correlation of affective and cognitive dimensions of empathy with the demographic characteristics of the instructors.

MethodsStudy designThe study design was a quantitative, observational, and cross-sectional study that integrated instruments to assess the characteristics of the participants and the TECA scale10. The study followed the simulation extensions for Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statements13.

SettingThe study was conducted during the first semester of 2024 at a multisite private university in Chile. The recruitment process included email invitations and online explanatory meetings organized during April 2024. Data collection was performed between May and June 2024.

ParticipantsThe eligibility criteria were to be a healthcare professional recruited as a simulation instructor at a specialized simulation unit created by a private university in Chile in January 2024. The exclusion criteria were to be part of the research team. The final target population consisted of 48 simulation instructors, from different professions and four cities in Chile. All of them were invited to participate in the study.

Sample size and error estimationConsidering a 95% confidence interval and 5% error, the estimated sample size was 43 participants. The final sample consisted of 36 participants, representing an 8% error, for the same 95% confidence interval.

VariablesThe variables considered in the study were empathy as a single variable and four dimensions of empathy related to the emotional and cognitive abilities to be empathetic. Other variables included were the formative level, simulation experience, professional background, age, and gender of participants.

Data sources/measurementThe instrument used to assess empathy was the TECA Scale. TECA included four subscales: Perspective Adoption (PA) and Emotional Understanding (EU), which form the cognitive dimension, and Empathic Distress (ED) and Empathic Joy (EJ), which represent the affective dimension. It provided a total score and specific scores for each subscale, classified based on statistical cut-off points adequate for healthcare professionals according to the authors instructions: scores between the 31st and 69th percentiles were considered average; 70th to 93rd percentiles, high; 7th to 30th percentiles, low; and below the 7th or above the 93rd percentiles, extreme. The scores helped identify empathic profiles based on standard deviations from the mean, providing helpful information for analyzing empathic abilities in healthcare contexts10. All the responses were collected using SurveyMonkey©.

BiasSelection bias was minimized by clearly defining eligibility and exclusion criteria, ensuring that the target population consisted of simulation instructors across various professions and locations in Chile, and inviting all eligible participants to avoid systematic exclusion13. The recruitment procedure included email invitations and synchronous online explanatory meetings. These actions enhanced accessibility and transparency. Measurement bias was mitigated using a validated instrument, the TECA scale, which provided standardized scoring criteria for empathy dimensions. The research team also explicitly reported the response rate and sample representation, addressing non-response bias by calculating the margin of error for the achieved sample size, while prioritizing respect for ethics norms of voluntary participation. The cross-sectional design ensured temporal consistency in data collection while maintaining transparency in methodology to reduce potential reporting biases.

Data analysisJASP 0.19.1 software was used for analysis, with a statistical significance of p<0.05. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, median, Std. Deviation, IQR, minimum and maximum) and relational analyses with Pearson's r or Spearman's Rho and ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis (H) were used, depending on the normality of the sample. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality.

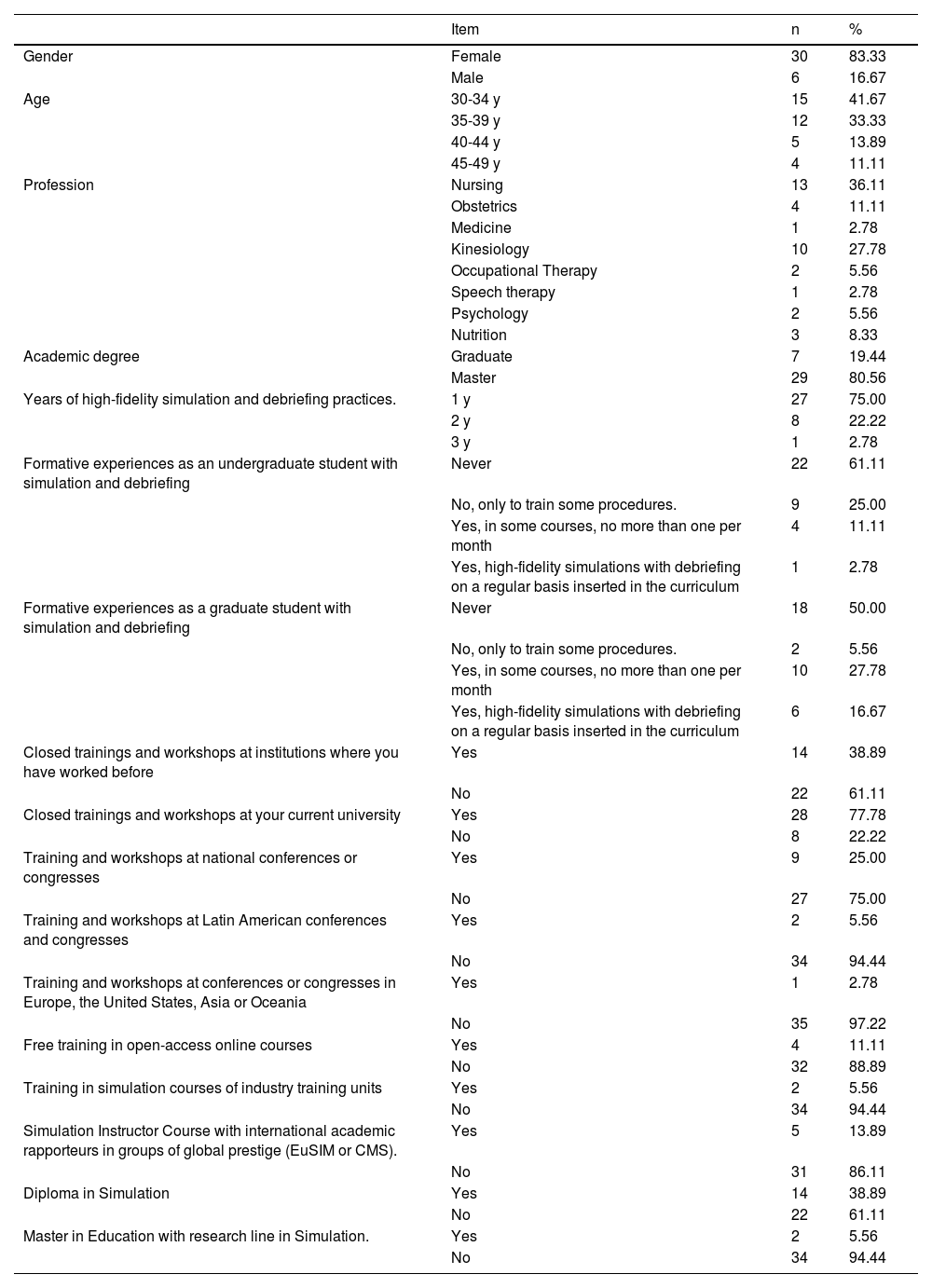

ResultsMost of the participants were women (83.33%), aged 30–34 years (41.67%), and held a master's degree (80.56%). Participants represented eight health-related professions, with most being nurses (36.11%) and kinesiologists (27.78%). Most had one year of experience in high-fidelity simulation and debriefing practices (75.00%). As undergraduate students, 61.11% reported no exposure to simulation and debriefing, while 16.67% experienced regular high-fidelity simulations as graduate students.

Regarding professional development, 77.78% participated in closed training programs and workshops at their current universities, while only 25.00% attended national conferences. Participation in Latin American and global conferences was rare (5,56% and 2.78%). Inside the group, 38.89% completed diplomas in simulation, while only 5.56% pursued a master's degree in education focusing on simulation (Table 1).

Demographic and professional characteristics of undergraduate simulation instructors.

| Item | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 30 | 83.33 |

| Male | 6 | 16.67 | |

| Age | 30-34 y | 15 | 41.67 |

| 35-39 y | 12 | 33.33 | |

| 40-44 y | 5 | 13.89 | |

| 45-49 y | 4 | 11.11 | |

| Profession | Nursing | 13 | 36.11 |

| Obstetrics | 4 | 11.11 | |

| Medicine | 1 | 2.78 | |

| Kinesiology | 10 | 27.78 | |

| Occupational Therapy | 2 | 5.56 | |

| Speech therapy | 1 | 2.78 | |

| Psychology | 2 | 5.56 | |

| Nutrition | 3 | 8.33 | |

| Academic degree | Graduate | 7 | 19.44 |

| Master | 29 | 80.56 | |

| Years of high-fidelity simulation and debriefing practices. | 1 y | 27 | 75.00 |

| 2 y | 8 | 22.22 | |

| 3 y | 1 | 2.78 | |

| Formative experiences as an undergraduate student with simulation and debriefing | Never | 22 | 61.11 |

| No, only to train some procedures. | 9 | 25.00 | |

| Yes, in some courses, no more than one per month | 4 | 11.11 | |

| Yes, high-fidelity simulations with debriefing on a regular basis inserted in the curriculum | 1 | 2.78 | |

| Formative experiences as a graduate student with simulation and debriefing | Never | 18 | 50.00 |

| No, only to train some procedures. | 2 | 5.56 | |

| Yes, in some courses, no more than one per month | 10 | 27.78 | |

| Yes, high-fidelity simulations with debriefing on a regular basis inserted in the curriculum | 6 | 16.67 | |

| Closed trainings and workshops at institutions where you have worked before | Yes | 14 | 38.89 |

| No | 22 | 61.11 | |

| Closed trainings and workshops at your current university | Yes | 28 | 77.78 |

| No | 8 | 22.22 | |

| Training and workshops at national conferences or congresses | Yes | 9 | 25.00 |

| No | 27 | 75.00 | |

| Training and workshops at Latin American conferences and congresses | Yes | 2 | 5.56 |

| No | 34 | 94.44 | |

| Training and workshops at conferences or congresses in Europe, the United States, Asia or Oceania | Yes | 1 | 2.78 |

| No | 35 | 97.22 | |

| Free training in open-access online courses | Yes | 4 | 11.11 |

| No | 32 | 88.89 | |

| Training in simulation courses of industry training units | Yes | 2 | 5.56 |

| No | 34 | 94.44 | |

| Simulation Instructor Course with international academic rapporteurs in groups of global prestige (EuSIM or CMS). | Yes | 5 | 13.89 |

| No | 31 | 86.11 | |

| Diploma in Simulation | Yes | 14 | 38.89 |

| No | 22 | 61.11 | |

| Master in Education with research line in Simulation. | Yes | 2 | 5.56 |

| No | 34 | 94.44 |

n=36; n: frequency; %: percentage; y: years.

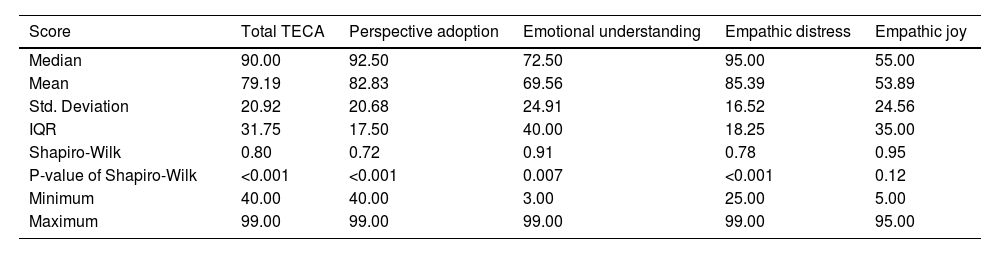

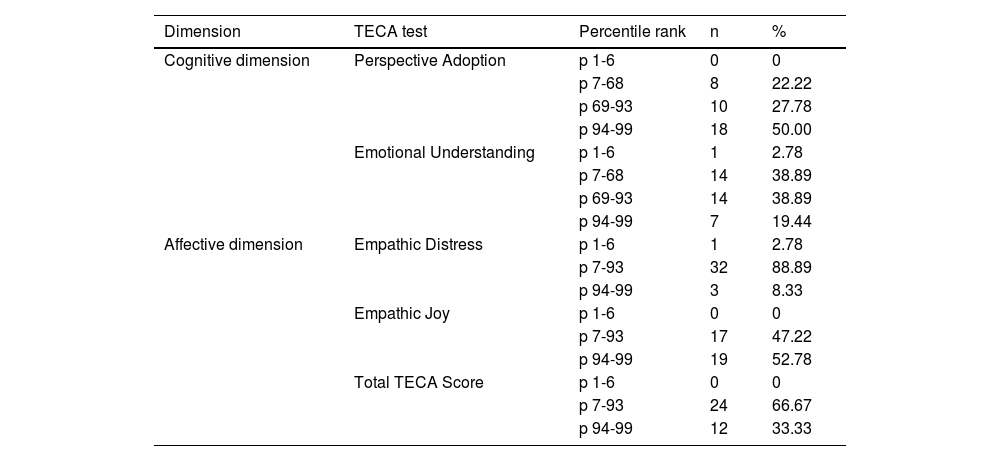

On the overall TECA score, 33.33% of the participants achieved extremely high scores (94th-99th percentile), while 66.67% were in the medium or high range (7th-93rd percentile). No participants had extremely low scores (1st–6th percentile), suggesting that this group has high overall levels of empathy.

Cognitive dimensionPerspective Adoption (PA): 50% of the participants obtained extremely high scores, reflecting an outstanding ability to understand different perspectives. 27.78% were in the high range inside this dimension (69th–93rd percentile), showing significant ability. 22.22% had low scores (7th–68th percentile) and no participant obtained extremely low scores (1st–6th percentile).

Emotional Understanding (EU): 38.89% achieved high or low scores, while 19.44% obtained extremely high scores. Only 2.78% scored in the extremely low scores, indicating that the majority possess a solid foundation for interpreting the emotions of others.

Affective dimensionEmpathic Distress (ED): 88.89% of the participants were in the moderate range in the dimension (percentile 7-93), reflecting an adequate balance between emotional resonance and self-control. Some 8.33% obtained extremely high scores, which could be associated with a greater tendency to emotional over-involvement. 2.78% presented extremely low scores (1st–6th percentile).

Empathic Joy (EJ): 52.78% reached extremely high scores inside the dimension, which shows a remarkable capacity to share positive emotions. 47.22% were in the moderate range, and no participants scored extremely low (Table 2).

Percentile distribution of TECA scores by dimension.

| Score | Total TECA | Perspective adoption | Emotional understanding | Empathic distress | Empathic joy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 90.00 | 92.50 | 72.50 | 95.00 | 55.00 |

| Mean | 79.19 | 82.83 | 69.56 | 85.39 | 53.89 |

| Std. Deviation | 20.92 | 20.68 | 24.91 | 16.52 | 24.56 |

| IQR | 31.75 | 17.50 | 40.00 | 18.25 | 35.00 |

| Shapiro-Wilk | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.95 |

| P-value of Shapiro-Wilk | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.12 |

| Minimum | 40.00 | 40.00 | 3.00 | 25.00 | 5.00 |

| Maximum | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 95.00 |

n=36; n: Frequency; %: Percentage; p: Percentile.

Total TECA score had a median score of p90 and a mean score of p79.19 (SD=20.92; IQR=31.75). The minimum and maximum scores varied across the subscales, with the Total TECA score ranging from p40 to p99, and other subscales also showing a similar range, except for Emotional Understanding, which had a minimum of p3. Shapiro-Wilk test shows significant deviations from normality (p<0.05) for Total TECA, Perspective Adoption, Empathic Distress, and Emotional Understanding (Table 3).

Descriptive statistics of percentiles of TECA scores by dimension.

| Dimension | TECA test | Percentile rank | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive dimension | Perspective Adoption | p 1-6 | 0 | 0 |

| p 7-68 | 8 | 22.22 | ||

| p 69-93 | 10 | 27.78 | ||

| p 94-99 | 18 | 50.00 | ||

| Emotional Understanding | p 1-6 | 1 | 2.78 | |

| p 7-68 | 14 | 38.89 | ||

| p 69-93 | 14 | 38.89 | ||

| p 94-99 | 7 | 19.44 | ||

| Affective dimension | Empathic Distress | p 1-6 | 1 | 2.78 |

| p 7-93 | 32 | 88.89 | ||

| p 94-99 | 3 | 8.33 | ||

| Empathic Joy | p 1-6 | 0 | 0 | |

| p 7-93 | 17 | 47.22 | ||

| p 94-99 | 19 | 52.78 | ||

| Total TECA Score | p 1-6 | 0 | 0 | |

| p 7-93 | 24 | 66.67 | ||

| p 94-99 | 12 | 33.33 |

n=36.

A statistically significant difference was found between gender and the Total TECA score, Emotional Understanding, and Empathic Distress (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.05), with men achieving higher percentiles.

Significant differences were also observed in the TECA score percentiles for the subdimensions of Empathic Distress and Emotional Understanding based on participation in specific training activities. In the Empathic Distress subdimension, ED scores were higher among instructors who received training (H=4.421, p=0.035; Tukey's test, p=0.023). Conversely, in the Emotional Understanding subdimension, EU scores were higher among instructors who had not participated in training sessions or workshops during national conferences (H=5.285, p=0.022; Tukey's test, p=0.041).

No significant correlations were found between the TECA score and variables such as years of high-fidelity simulation and debriefing experience, academic degree, age, or possession of a Diploma in Simulation or a Master's degree in Education with a research focus in Simulation.

DiscussionThe main results of this study align with previous research suggesting that simulation can foster empathy2,3 and provide additional insights into instructors’ specific cognitive and affective empathic profiles.

- a.

Empathic Profiles

Our study's high overall empathy scores are consistent with prior research suggesting that healthcare professionals, particularly those engaged in education and simulation, tend to demonstrate high levels of empathy8. However, our findings also reveal nuances in the distribution of cognitive and affective empathy, with a notable predominance of high scores in Perspective Adoption (PA) and Empathic Joy (EJ), contrasted with more varied scores in Emotional Understanding (EU) and Empathic Distress (ED). This variability highlights the complex nature of empathy, which is influenced by individual characteristics and experiences1.

Interestingly, while prior studies have documented that excessive affective empathy (e.g., heightened Empathic Distress) can contribute to burnout and emotional exhaustion1,9, our study identified that 88.89% of participants scored in the moderate range for ED, suggesting a balanced emotional engagement in most cases. However, 8.33% scored in the extremely high range, which, according to TECA authors, is related to potential vulnerability to emotional over-involvement10. As previously stated, if students’ emotions are negative, the instructor can feel overwhelmed and affect their mental health1,9. Psychological research has shown that a dynamic and reciprocal relationship exists between the emotional states of students and educators, particularly in interpersonal teaching contexts14. Debriefings occur in small groups with interpersonal interaction, where high levels of empathic distress may lead instructors to absorb students’ emotional states, which can compromise their ability to be neutral when conducting post-simulation debriefing. Echoing with the participant's emotivity may influence the tone or content of debriefing, by amplifying emotional reactions or avoiding difficult conversations to mitigate distress. Such responses can affect the learning climate and reduce the effectiveness of simulation debriefings, which rely on balanced and reflective discussions11. Therefore, educators’ emotional training is essential for their well-being and preserving the simulation experience integrity.

Another finding of this study was the comparatively lower and more variable scores in the EU subscale. The EU is the empathy domain, which reflects the ability to perceive and interpret the emotions of other persons accurately10. The variation in EU scores may indicate differing levels of affective attunement among instructors, which could influence their ability to respond effectively to students’ emotional signals. Krishnasamy et al.8 identified essential elements in developing empathy and compassion in medical education: perceiving the patient as a whole person, understanding the conceptual foundations of empathy, navigating the training environment, and being guided by professional values. The lower EU scores in this sample suggest insufficient emphasis on the second element, explicit understanding of the empathy concept, within instructors’ formative experiences. It is also possible that institutional learning environments that prioritise technical proficiency over reflective or humanistic dimensions may contribute to underdeveloped emotional recognition capacities.

- b.

Gender Differences in Empathy

The observed gender differences in empathy scores align with existing literature that suggests men and women may differ in their empathic responses9. Our findings indicate that men scored higher on Total TECA, Emotional Understanding, and Empathic Distress, which contrasts with some studies suggesting that women typically demonstrate higher affective empathy6, but could be explained by social and professional factors that influence these gender differences15,16.

- c.

Empathy and Simulation Training

One of the most significant findings is the relationship between participation in training activities and empathy subdimensions. Instructors who had participated in simulation training programs scored higher in ED, suggesting that structured educational experiences may promote this empathy dimension, in a similar manner as reported in previous research focused on the effect of training on students’ emotional competencies4,7. Conversely, instructors who had not participated in national conferences scored higher in EU. Future studies should explore the impact of different training modalities on empathy development, whether structured training enhances emotional resilience or inadvertently increases emotional burden.

Our study did not find significant correlations between TECA scores and variables such as years of experience in high-fidelity simulation, academic degree, or advanced education in simulation. This finding contrasts with prior studies suggesting that professional experience and higher education are associated with increasing empathy5. A possible explanation is that most of the participants in our study were young instructors, and personal traits may influence their empathy levels more than formal other variables.

- d.

Implications for Simulation-Based Education

The results underscore the importance of considering empathy as a critical competency for simulation instructors. Teacher empathy has a significant influence on student motivation and engagement in other educational contexts, fostering a supportive and inclusive learning environment that enhances students’ self-confidence15. Empathetic teachers can connect with students on a personal level, encouraging active participation with the subsequent better learning experience16. They can also adapt their methods to meet diverse student needs, enhancing motivation through personalized learning experiences16. Given the role of empathy in creating psychologically safe learning environments11,12 and the potential implications of the affective dimension of empathy in simulation instruction14, institutions should integrate targeted training programs that balance cognitive and affective empathy development.

In healthcare, there is evidence of different approaches to teaching cognitive and affective empathy to students and professionals17, with high heterogeneity in results that makes it difficult to confirm the effects in learning17,18. There is no evidence of the impact of this training on patients until now, nor have studies focused on instructors’ training in simulation. Consider TECA10 as a tool to identify empathy profiles and their components in simulation instructors, which could help assess the impact of training in recognizing and managing emotions in students and themselves. Furthermore, strategies to mitigate potential emotional over-involvement should be explored, especially if the instructors show higher ED scores. These strategies can include resilience training and peer support mechanisms19. To improve the EU, integrating structured reflective practices and targeted training in affective competencies using standardized patients20 or narrative medicine21 could strengthen instructors’ capacity to model and foster students’ capacities to manage their own or others’ emotions.

While this study provides valuable insights, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, the sample size was slightly below the estimated target, leading to an 8% margin of error, which then determined the need to proceed with caution when interpreting results. Additionally, the study was conducted within a single university system, potentially limiting generalizability. Future research should address these sample limitations and consider interventional and longitudinal designs to explore interventions to optimize empathy in simulation instructors and assess how empathy evolves with training. Also, studies that can determine the impact of empathy on students’ learning and psychological safety, or the transference to patients, will be valuable.

Practice ImplicationsThe findings of this study suggest that empathy profiling using validated tools such as the TECA can offer valuable insights into instructors’ cognitive and affective capacities in simulation-based education. These profiles can guide the design of targeted professional development programs that promote emotional resilience and foster balanced empathy. Institutions should consider integrating reflective practices and emotional self-regulation strategies into instructor training, especially for those scoring high in empathic distress. Instructors’ ability to recognize and respond to learners’ emotional cues while maintaining psychological safety is critical to effective debriefing and student engagement. Empathy-informed faculty development has the potential to improve educational outcomes and support the broader goal of cultivating compassionate, patient-centered healthcare professionals.

ConclusionThis study provides new evidence on the empathy profiles, including cognitive and affective dimensions, in novice simulation instructors. The high levels of PA and EJ suggest strengths in relational teaching, while variability in EU and ED points to areas where instructors may benefit from support strategies or specific faculty development programs that promote emotion management and psychological safety. Integrating tools like TECA to assess empathy profiles can inform tailored training strategies and resilience-building interventions. Future research should explore the longitudinal effects of such interventions and evaluate their impact on student engagement, learning outcomes, and patient-centered communication competency.

Relevant informationPart of the data of this article was presented in the VIII Simulation Chilean Congress, and the abstract of this presentation was included in an special number of Revista Chilena de Enfermería, as part of the Congress’ official report. The link to this document is https://doi.org/10.5354/2452-5839.2025.77649.

Ethical considerations:The institutional ethics committee approved the study (Act 169-23). Instructors participated voluntarily after an informed consent procedure.

Funding sourceThis research receives an Academic Innovation Grant from the Universidad San Sebastián (041-2023). This institution was not involved in the design of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing of the article, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the author(s) used Grammarly in order to improve the readability and language of the manuscript considering that the native language of the authors is Spanish. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.