To investigate the effects of acupuncture added to standard postoperative care on postoperative pain and nausea-vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

DesignA prospective randomized clinical trial.

SettingUniversity of Health Science Kartal Dr Lütfi Kırdar Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

ParticipantsEighty patients, 18-65 years old, American Society of Anesthesiologist's physical status of I-III: 40 subjects in the acupuncture (real points) group and 40 in sham (1cm lateral to the real points and more superficial) group.

InterventionsAcupuncture needles were inserted in 7 points including bilateral ST 36, LI 4, P 6 and extra 1 10minutes before starting anesthesia induction. The needles were manually rotated periodically throughout the surgical procedure. All patients were given 1.5mg/kg tramadol and 10mg metoclopramide intravenously 10minutes before surgical completion. When the visual analog scale was ≥ 5, 1g of paracetamol was administered intravenously and then 75mg of diclofenac sodium was administered intramuscularly. Acupuncture needles were removed after extubation.

Main measurementsHemodynamic parameters were recorded during the surgical procedure and visual analog scale, first analgesic requirement, total amount of analgesic requirement during postoperative 24-hours, nausea-vomiting, necessity for antiemetic medication and side effects were evaluated at postoperative 0, 2nd, 6th, 12th, and 24th hours.

ResultsIn the acupuncture group, visual analogue scale values were lower (p < 0.001), the first analgesic requirement was later (p < 0.001), the time to first analgesic requirement was longer (p < 0.001) and the incidence of nausea-vomiting was lower during the 0, 2nd, and 6th hours (p = 0.003, p = 0.01, p = 0.02). Analgesic and antiemetic requirements were also lower in the first 24hours (p < 0.001).

ConclusionsAcupuncture treatment reduces postoperative pain and nausea-vomiting incidence, antiemetic and analgesic requirements especially in the first 6hours, and its combination with conventional postoperative treatment is effective and safe.

Investigar los efectos de la acupuntura, añadida a la atención posoperatoria estándar, sobre el dolor posoperatorio y las náuseas y vómitos, tras una colecistectomía laparoscópica.

DiseñoEnsayo clínico aleatorizado prospectivo.

EmplazamientoUniversidad de Ciencias de la Salud Kartal Dr. Lütfi Kırdar Training and Research Hospital, Estambul, Turquía.

ParticipantesOchenta pacientes, de entre 18 y 65 años, estado físico I-III según la Sociedad Americana de Anestesiólogos: 40 sujetos en el grupo de acupuntura (puntos reales) y 40 en el grupo falso (1cm lateral a los puntos reales, y más superficial).

IntervencionesSe insertaron agujas de acupuntura en 7 puntos, incluyendo ST 36 bilateral, LI 4, P 6 y 1 10min extra antes de comenzar la inducción anestésica. Las agujas se rotaron manualmente periódicamente durante todo el procedimiento quirúrgico. Todos los pacientes recibieron 1,5mg/kg de tramadol y 10mg de metoclopramida por vía intravenosa 10min antes de la finalización quirúrgica. Cuando la escala analógica visual era ≥ 5, se administró 1g de paracetamol por vía intravenosa y luego se administraron 75mg de diclofenaco sódico por vía intramuscular. Las agujas de acupuntura se retiraron después de la extubación.

Mediciones principalesLos parámetros hemodinámicos se registraron durante el procedimiento quirúrgico y la escala visual analógica, el primer requerimiento analgésico, la cantidad total de requerimiento analgésico durante las 24h posoperatorias, las náuseas y los vómitos, la necesidad de medicación antiemética y los efectos secundarios se evaluaron en el posoperatorio tras 0, 2, 6, 12 y 24h.

ResultadosEn el grupo de acupuntura, los valores de la escala visual analógica fueron más bajos (p < 0,001), el primer requerimiento analgésico fue posterior (p < 0,001), el tiempo para el primer requerimiento analgésico fue más largo (p < 0,001) y la incidencia de náuseas/vómitos fue menor durante las horas 0, 2.ª y 6.ª (p = 0,003, p = 0,01, p = 0,02). Los requerimientos analgésicos y antieméticos también fueron menores en las primeras 24h (p < 0,001).

Conclusionesel tratamiento de acupuntura reduce el dolor posoperatorio y la incidencia de náuseas y vómitos, los requisitos antieméticos y analgésicos, especialmente en las primeras 6h, y su combinación con el tratamiento posoperatorio convencional es eficaz y segura.

Laparoscopy is a widely used semi-invasive surgical procedure in which the prevention of nausea, vomiting and a painless postoperative period is highly prioritized. Due to its outpatient characteristics, it requires patients to be discharged after a short time. Postoperative pain is a big challenge for clinicians and the more than 80% of surgical patients experience postoperative pain at different intensities.1 Postoperative pain is one of the major factors for the prolongation of hospitalization.

Opioid analgesics are usually the first treatment choice for postoperative pain management but the recovery of patients may be prolonged due to their untoward side effects such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness and decreased gastrointestinal motility.2 The fear of dose-dependent serious side effects leads physicians to under-prescribe analgesics and results in under-management of postoperative pain.3

Despite a number of studies over decades and advances in medical pharmacology, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) remains a significant problem in modern anesthetic practice and results to delays in recovery and ambulation of patients, as well as wound dehiscence, pulmonary aspiration or dehydration.4 PONV affects the quality of postoperative care and decreases the patient's satisfaction after surgery. A recent meta-analysis indicated that a multimodal approach with a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods would be more beneficial to reduce the baseline risk of PONV.5

The World Health Organization reported the Traditional Medicine Strategy between 2014 and 2023 emphasizing that traditional and complementary medicine is an important and often underestimated health resource.6 Acupuncture is a well-known complementary and alternative medicine which has been used in many clinical conditions in China for more than 3000 years. Studies concerning the efficacy of acupuncture as adjuvant treatment on postsurgical patients have gained popularity. However, the studies have conflicting results. Madsen et al.7 suggested that acupuncture had no effect on postoperative pain, although studies using different surgical procedures resulted in positive outcomes.8–10

In previous studies, acupuncture was used as an effective non-pharmacological method to reduce PONV after general anesthesia for different surgical procedures.11,12

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture for postoperative pain and nausea-vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

MethodsThis prospective randomized clinical trial was conducted after the approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee (Decision no: 2019/514/146/9-(28.01.2019)) and written informed consent of all the participants, according to the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Potential benefits and possible side effects of acupuncture were explained to all patients.

All acupuncture procedures were performed by an expert acupuncturist. The blinding to the study of the acupuncturist is a debatable issue in the literature and a previous report indicated that the studies related with acupuncture cannot actually be double-blinded.13 The expert acupuncturist who conducted the intervention was different from the anesthesiologists who examined the patients for PONV. The patient and examiner physician were unaware of the allocation of the groups in our study. Therefore, the trial was considered to be double-blinded.

Study populationThis study was conducted in a 630-bed academic tertiary hospital in which approximately 15,000 surgical procedures are performed per year. According to institutional policy, all elective surgical patients are evaluated preoperatively by an anesthesiologist for preoperative risk assessment. The patients scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy from March to June 2019 were included the study.

An anesthesiologist assigned the study population according to inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteriaPatients hospitalized for more than 24hours, aged between 18-65 years, in American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I, II and III risk groups were included the study.

Exclusion criteriaPatients with severe comorbidities, using antiemetic and/or analgesics within 24hours before surgery, cognitive impairment, pregnancy, patients with dementia, neurologic or psychiatric disorders, patients with coagulopathies, and presence of infection at the acupuncture sites were excluded.

Patients were allocated to one of two groups as real acupuncture (Group I, n=40) and sham acupuncture (Group II, n=40; 1cm lateral to the real points and more superficial) with usual care. Randomization was done by an anesthesia nurse not involved in the study according to the operation lists. The patients listed with odd numbers were included in Group I; the patients listed with even numbers were included in Group II. We estimated the Apfel score of all patients before the surgical procedure to identify the risk stratification for PONV.

Acupuncture interventionsFDA-approved acupuncture needles of 5cm length and 0.2mm diameter were used in all interventions. Manual needle stimulation was performed and patients were asked about dullness, tingling sensation, heaviness or sourness in the first 10minutes.

Before anesthesia induction, 7 acupuncture points (bilateral St-Stomach 36, Li- Large intestinal 4, P-Pericardium 6, extra 1) (four-finger space below the patella in the depression on the lateral side of the tibia, on the dorsum of the hand-between the 1st and 2nd metacarpal bones, between the tendons of the palmaris longus and flexor carpi radialis muscles, 4cm proximal to the wrist crease, between the medial ends of the two eyebrows at the root of the nose) were cleaned with alcohol pads and then fine sterile acupuncture needles were inserted into 80 patients. All needles were kept in place and the needles were rotated up to the end of surgery in all groups. Acupuncture points were determined based on our literature reviews and experience.

A standard anesthesia protocol was administered to all patients including intravenous administration of fentanyl 2μg/kg, propofol 2-3mg/kg and 0.6mg/kg rocuronium. Maintenance of anesthesia was provided by sevoflurane (2%) to maintain the bispectral index scale (BIS) values between 40-60. Monitoring of all patients included electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximetry, capnography, non-invasive blood pressure and respiratory sevoflurane concentration. Intravenous fluid management was achieved by infusion of multiple electrolyte solutions based on the preoperative deficit and the intraoperative loss of the patient. Respiratory rate, tidal volume and peak pressure were set to adjust the end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) level between 35 and 45mmHg. Before CO2 insufflation, nasogastric tube decompression was employed and patient was placed in a head-up and left side down tilt position. Pneumoperitoneum was created with intraabdominal pressure of 12mmHg by CO2 insufflation.

Tramadol 1.5mg/kg and metoclopramide 10mg were administered intravenously to all patients 10minutes before the end of the procedure. Neostigmine (0.05mg/kg) and atropine (0.025mg/kg) were administered intravenously to reverse the residual effect of rocuronium. Acupuncture needles were removed after extubation and the patients were transferred to the recovery room. Patients were followed-up for 2hours in the recovery room and then transferred to the ward.

Data collectionDemographic characteristics (age, gender, weight and height), ASA physical status and Apfel scores of all patients were recorded. Intraoperative hemodynamic parameters [systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP-DBP), heart rate (HR)], BIS values, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), EtCO2 values, duration of surgery and number of patients with knowledge of acupuncture were recorded. Pain scores were assessed with Visual Analog Scale (VAS) just after arrival (0. hour) and at the 2nd hour in the recovery room. If the score was ≥5, paracetamol 1g intravenously and then diclofenac sodium 75mg intramuscular were administered for postoperative pain. VAS was also assessed at 6th, 12th and 24th hours. Time to first analgesic requirement, 24-hour analgesia requirements, nausea-vomiting through questions or clinical observation, antiemetic needs in first 24hours and side effects (hypo/hypertension, vertigo, dizziness etc.) were recorded during the postoperative period.

The primary outcome measure of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture added to standard postoperative care after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Secondary outcomes included PONV according to Apfel score and time windows (these were divided into 5 phases: until discharge from the recovery room: 0, 2nd, 6th, 12th, 24th hours for pain and PONV), use of analgesics and antiemetics.

Statistical analysisThe demographic characteristics and data collected for patients were entered into the IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for Statistics) version 25. Variables were characterized using mean, maximum and minimum values, and percentage values were used for qualitative variables. Normal distributions were reported as mean±SD and the Student t-test was used for comparisons between groups. Pearson chi-square test and if the group was small, Fisher exact test were used for analysis of qualitative variables. Nonparametric continuous variables were recorded as median and intermittent distribution and compared using Mann-Whitney U test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

G * power program (G * Power 3.1.9.2 for Windows 10) was used to calculate the sample size. With confidence level 95%, the alpha level 5%, the error margin 5% and the effect size 0.50, the number of patients required for each group is 41 and the total number of patients required is 82. For randomization, the program on https://www.randomizer.org/ was used and patients were randomized to two groups. However, after randomization, one patient from both groups gave consent to the study, but they wanted to leave before the end of the study. Therefore, the results were evaluated with 40 patients in both groups.

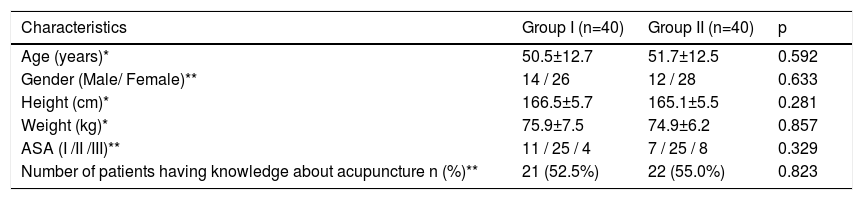

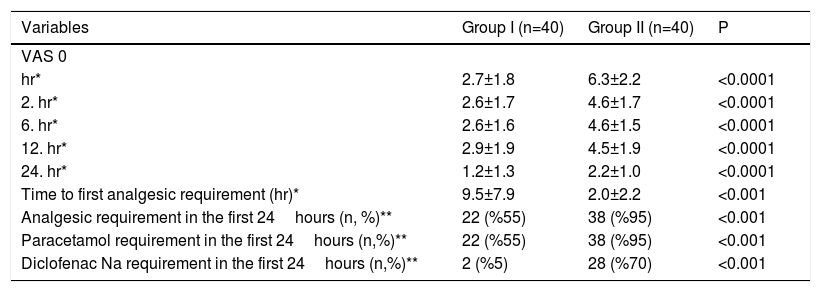

ResultsThere was no statistical significance between the groups with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). There was no difference between the groups according to hemodynamic parameters. The VAS values of patients in Group I were significantly less than the VAS values of patients in Group II at all time periods (p<0.0001). The time to first analgesic requirement of patients in Group II was shorter than for those in Group I (2.0 ± 2.2hours versus 9.5 ± 7.9hours) (p<0.001). A total of 60 postoperative patients needed analgesics within the first 24hours. These patients were more likely to be in Group II [22 (55%) patients versus 38 (95%) patients], (p<0.001). As analgesics, 55% of patients in Group I required paracetamol and 5% diclofenac Na, while these rates were 95% and 70% in Group II, respectively. The analgesic requirements of patients in Group II were more than those in Group I, and the difference was significant (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Demographics and primary clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics | Group I (n=40) | Group II (n=40) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 50.5±12.7 | 51.7±12.5 | 0.592 |

| Gender (Male/ Female)** | 14 / 26 | 12 / 28 | 0.633 |

| Height (cm)* | 166.5±5.7 | 165.1±5.5 | 0.281 |

| Weight (kg)* | 75.9±7.5 | 74.9±6.2 | 0.857 |

| ASA (I /II /III)** | 11 / 25 / 4 | 7 / 25 / 8 | 0.329 |

| Number of patients having knowledge about acupuncture n (%)** | 21 (52.5%) | 22 (55.0%) | 0.823 |

Postoperative pain asessment of the study groups.

| Variables | Group I (n=40) | Group II (n=40) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS 0 | |||

| hr* | 2.7±1.8 | 6.3±2.2 | <0.0001 |

| 2. hr* | 2.6±1.7 | 4.6±1.7 | <0.0001 |

| 6. hr* | 2.6±1.6 | 4.6±1.5 | <0.0001 |

| 12. hr* | 2.9±1.9 | 4.5±1.9 | <0.0001 |

| 24. hr* | 1.2±1.3 | 2.2±1.0 | <0.0001 |

| Time to first analgesic requirement (hr)* | 9.5±7.9 | 2.0±2.2 | <0.001 |

| Analgesic requirement in the first 24hours (n, %)** | 22 (%55) | 38 (%95) | <0.001 |

| Paracetamol requirement in the first 24hours (n,%)** | 22 (%55) | 38 (%95) | <0.001 |

| Diclofenac Na requirement in the first 24hours (n,%)** | 2 (%5) | 28 (%70) | <0.001 |

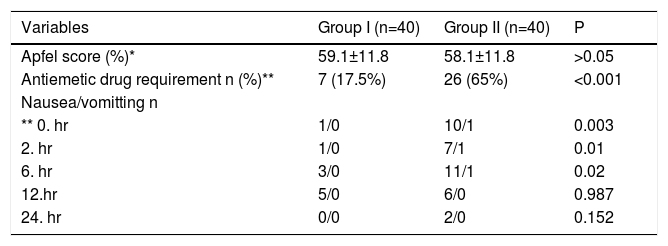

Since the number of cases with vomiting findings was low (n=3), statistical analysis could not be conducted. Patients in Group II received more antiemetic medication than those in Group I (65.0% versus 17.5%) (p<0.001). Regarding the Apfel score, this ratio was similar for both groups (59.1 ± 11.8 for Group I and 58.1 ± 11.8 for Group II). In addition, although there was no difference between Apfel scores of patients without nausea-vomiting in both groups, the number of patients without nausea-vomiting in group I was high. Nausea/vomiting was more common in Group II for the first 6hours (2.5% in Group I, 27.5% in Group II, p = 0.003 for 0hours, 2.5% in Group I, 20% in Group II, p = 0.01 for 2nd hour, 7.5% in Group I, 30% in Group II, p = 0.02, for 6th hour); however, there was no difference between groups in terms of nausea/vomiting at 12th and 24th hours (p=0.987 and p=0.152, respectively) (p>0.05) (Table 3).

Postoperative asessments of the study groups with respect to nausea/vomiting.

No major side effects of the acupuncture application were observed. Although hypotension was observed in 5 patients in the acupuncture group and 2 patients in the control group, the difference was not significant. (p=0.152).

Although it is not one of the parameters we investigated, at the end of our study, we encountered an interesting and pleasing result. The ward nurses postoperatively stated which patient was in the real and which patient was in the sham group (according to the patients’ faces).

DiscussionPostoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a complication that, along with PONV can significantly compromise the patient's quality of life. Acupuncture is also an alternative and widely-used therapy for the prevention of postoperative pain and PONV in eastern medicine. However, it has not been able to find its real place in western medicine and has not entered the treatment guidelines considering there is still insufficient data about the treatment. We assessed the effectiveness of acupuncture in treating postoperative pain and nausea-vomiting.

Acupuncture is thought to suppress pain by activating a number of neurotransmitters or modulators such as opioid peptides, norepinephrine, serotonin and adenosine although the effect on pain is uncertain.14 It was reported that the maximum release of endorphins is at 20minutes in acupuncture treatment, then decreases, and the session duration should be 20-40minutes in order to achieve acupuncture analgesia in humans.15 In our study, we performed acupuncture sessions with approximately similar durations and as one session in all cases.

We found that patients treated with acupuncture added to standard postoperative care had less pain and nausea-vomiting especially in the first 6hours, and used less analgesics and antiemetics in the first 24hours after laparoscopic cholecystectomy compared with those treated with standard postoperative care (p<0.001, p<0.01, p<0.001).

Wu et al.16 reported that conventional acupuncture and transcutaneous electric acupoint stimulation (TEAS) were associated with less postoperative pain than control treatment on day 1 post surgery, while electroacupuncture was similar to control in their systematic review and meta-analysis. However, they observed that conventional acupuncture and electroacupuncture showed no benefit in reducing opioid analgesic use compared with the control group, but it decreased only in the TEAS group. This result conflicts with our study. However, Wu et al.’s study is a metaanalysis involving 12 studies in which different acupuncture techniques (auricular acupuncture, TEAS, acupuncture or electroacupuncture) at different times (before surgery, after surgery or before and after surgery) were applied for various surgeries (lower abdominal surgery, gynecologic, spinal surgery, hemorrhoidectomy or total hip arthroplasty) and sometimes VAS and sometimes Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)-11 were used for pain assessment. We think that the difference in analgesic consumption may be due to these reasons. As a result, they stated that acupuncture can be used as an adjuvant therapy in postoperative pain in accordance with our study.

Levy at al.17 included 425 patients and compared acupuncture with standard of care pain treatment (acupuncture group) or standard of care treatment only (control group) following surgery. Consistent with our results, they found that the acupuncture group had a lower VAS (at least 40%) both at rest and in motion on the first day and no side effects were observed. They reported that acupuncture with standard care may improve pain control in the postoperative setting.

Sun et al.18 recruited 1166 patients; 608 were assigned to the acupuncture group and 558 to the control group in 15 studies. They applied acupuncture, moxibustion, TEAS, and acupressure and postoperative pain was significantly lower in the acupuncture group compared to the sham group at 8 and 72hours after surgery. A significant difference was also found in the mean opioid consumption at 8, 24, and 72hours between the acupuncture and control group.

Langenbach et al.9 reported NRS as 2.7 in the verum group, 4.0 in the sham group, and 4.1 in the conventional analgesia (oral diclofenac and metamizole, local lidocaine) group in studies where they performed sham-controlled acupuncture for postoperative pain control after hemorrhoidectomy. They also reported that acupuncture may be an effective adjunct to conventional analgesia and that more studies are needed to report less analgesic requirements in the verum group. Our results indicated that the VAS values and analgesic consumption were significantly lower in the acupuncture group of patients in the first 24hours postoperatively. These differences may be due to the fact that our study included only conventional acupuncture for a single type of surgery.

Many studies showed the effects of acupuncture on nausea/vomiting by regulating gastric myo-electrical activity and vestibular activities in the cerebellum,19,20 modulating the actions of the vagal nerve and autonomic nervous system, reducing vasopressin-induced nausea and vomiting and suppressing retrograde peristaltic contractions.21 There is sound evidence that PC6 stimulation is effective for the prevention of PONV. In our study, we investigated whether the combined use of PC6 and other points combined with antiemetics is more effective than antiemetic therapy only in patients who are not different in terms of the risk of nausea and vomiting according to Apfel scoring. For PC6 combined with other acupoints, interventions were performed before and after induction of anesthesia and during the operation. To be effective, it should be administrated before the emetic stimulus.22

We applied acupuncture to P6 and other points together with antiemetics before induction in laparoscopic cholecystectomy to evaluate postoperative pain and nausea-vomiting. We found that the incidence of PONV was less in the acupuncture group in the first postoperative 6hours (p<0.05). Martin et al.23 reported that the incidence of PONV after tonsillectomy surgery in children was significantly less with acupuncture plus antiemetic therapy than with just antiemetic therapy (7.0% vs 34.7%, p<0.001) during phase I and II recovery (in early terms). But they also found that there was no difference in PONV in the first 24hours. Fry et al.24 included 200 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and compared acupuncture with sham. Consistent with our results, they found that the incidence of nausea at two hours (early nausea) was significantly less in the acupuncture group (29%) than in the sham group (42%) (p=0.043). We believe that in all studies, including our study, better results could be achieved if acupuncture therapy was applied for a longer period of time.

LimitationsSince the number of cases with vomiting findings was low, statistical analysis could not be done or it would not be meaningful even if it was done, and it was evaluated with nausea.

ConclusionAcupuncture treatment was effective in the first 24hours for postoperative pain and especially in the first 6hours for nausea-vomiting control after laparoscopic cholecystectomy operation. It was concluded that it would be beneficial to use non-pharmacological treatments such as acupuncture treatment, which is quite noninvasive with few side effects, for treatment of postoperative pain and nausea-vomiting. It should even enter the treatment guides and awareness should be created by informing patients more about this issue.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

FundingAll medications and materials used in this study were provided by Kartal Dr. Lütfi Kırdar Training and Reseach Hospital which is a university-affiliated tertiary training government hospital.

Outlines of the studyAfter sample size calculation, the number of patients required for each group was 41 and the total number of patients required was 82. Patients were randomized to two groups. However, after randomization, one patient from both groups gave consent to the study, but they wanted to leave before the end of the study. Therefore, the results were evaluated with 40 patients in each group.

The authors thank all their colleagues in the general surgery department for their help in this research.