Muscle injuries are prevalent in sports practice among high performance athletes and amateurs. Considering the wide clinical variety of this morbidity (extension and different presentations), there is an interest in studying the effect of acupuncture on the treatment of pain related to muscle injury in an identical model. Microsystem acupuncture is a practical, economical, fast-acting therapeutic resource with few side effects.

MethodThis study is a clinical trial in which 22 patients undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) surgery were divided into two groups. In group 1, the participants received established rehabilitation treatment. Participants in group 2 received acupuncture treatment using nasal microsystem and cranial suture microsystem techniques, in addition to the rehabilitation program, to relieve muscle pain in the graft harvesting region. Participants were assessed for pain outcome by the Numerical Pain Scale (NPS) from the first to the sixth postoperative week.

ResultsBoth groups showed a statistically significant reduction in pain as treatment progressed; however, a better outcome was evident in the acupuncture-treated group compared with the control group from the second to the fourth week (p<0.001). There was also a significant reduction in pain score before and immediately after the acupuncture session on the fifth postoperative day (p<0.001).

ConclusionThe results of the present study suggest that the addition of acupuncture treatment with nasal microsystem and cranial suture microsystem techniques to the established rehabilitation treatment has brought benefits in reducing thigh muscle pain in the early postoperative period.

Las lesiones musculares son prevalentes en la práctica deportiva entre los atletas y aficionados de alto rendimiento. Considerando la amplia variedad clínica de esta morbilidad (extensión y diferentes presentaciones), existe interés por estudiar el efecto de la acupuntura en el tratamiento del dolor relacionado con la lesión muscular en un modelo idéntico. La acupuntura de microsistemas es un recurso terapéutico práctico, económico y de acción rápida, con pocos efectos secundarios.

MétodoEste estudio es un ensayo clínico realizado en 22 pacientes sometidos a cirugía de reconstrucción del ligamento cruzado anterior (LCA), que se dividieron en dos grupos: en el grupo 1, los participantes recibieron tratamiento establecido de rehabilitación, y en el grupo 2, los participantes recibieron tratamiento de acupuntura utilizando técnicas de microsistemas nasales y de sutura craneal, además del programa de rehabilitación para aliviar el dolor muscular en la región de extracción del injerto. Se evaluó el resultado del dolor de los participantes utilizando la Escala del Dolor Neuropático (NPS) desde la primera a la sexta semanas postoperatorias.

ResultadosAmbos grupos mostraron una reducción significativa del dolor a medida que progresaba el tratamiento; sin embargo, se evidenció un mejor resultado en el grupo tratado con acupuntura, en comparación con el grupo control desde la segunda a la cuarta semanas (p < 0,001). También se produjo una reducción significativa de la puntuación del dolor, antes e inmediatamente después de la sesión de acupuntura al quinto día postoperatorio (p < 0,001).

ConclusiónLos resultados del presente estudio sugieren que la adición de acupuntura con técnicas de microsistemas nasales y de sutura craneal al tratamiento de rehabilitación aportó beneficios en cuanto a reducción del dolor del músculo del muslo en el periodo postoperatorio temprano.

Muscle injuries are one of the most prevalent conditions in sports among high-performance athletes and amateurs, with an incidence ranging from 10% to 55%. They are caused by bruises, strains and lacerations, the latter being less frequent. Bruises and sprains are responsible for more than 90% of cases.1

Considering the wide clinical variety of this morbidity and the lack of a defined standard in its presentation, there are difficulties in producing studies with comparable results regarding the effect of proposed treatments, arousing interest in studying models of muscle injuries with the same size and location in humans.

In the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction (ACLR) technique with graft of semitendinosus and gracilis tendons, distal disinsertions and their proximal section are performed in the musculotendinous transition, individually.2

One of the potential complications of this technique is the occurrence of acute or chronic pain (which can last for up to three months) in the donor region, due to the muscle injury caused during surgery.3

Allopathic medications used for pain relief may cause health problems to patients, thus stimulating the search for new treatment modalities with fewer side effects.

Few studies have used acupuncture to treat sports injuries. There is evidence that this technique promotes immediate pain relief and modulates the immune system.4

Microsystem acupuncture is a practical, economical therapeutic resource, with few side effects and free from the risk of breaking anti-doping laws, and can be used as an alternative and adjunctive pain technique.5,6

The classic concept of acupuncture is based on the theory of vital energy (Qi) that flows through the body along meridians that have specific points through which energy can be accessed. The insertion of needles at these points allows the therapist to restore the patient's local and systemic energy harmony by rebalancing the flow of Qi.7,8

For Western medicine, acupuncture is therapy based on specific sensory neuronal stimulation that can be analyzed for its influence on neurological circuits. There is a consensus that the technique acts locally, regionally, and systemically. Needle insertion provides sensory stimulation, which can occur at several points and in different areas at the same time. It is believed that different combinations of points activate different pathways and that the character of the stimulus is fundamental to the therapeutic outcome.9,10

The integrity of the peripheral nervous system is necessary to obtain the results from acupuncture, and the possibility of reversing its analgesic effect using naloxone (opioid antagonist) is well known. The stimulus provoked by this type of intervention is mainly driven by A-delta nerve fibers and, in a smaller proportion, by C fibers, to the spinal cord dorsal horn. Running through the neospinothalamic and paleospinothalamic tracts, respectively, the impulse reaches the suprasegmental Central Nervous System (CNS).9

Depending on its characteristics, a peripheral sensory neurological stimulus can activate specific CNS nuclei and modulate the release and sensitivity to neurotransmitters, promoting qualitative changes in the synaptic regions.10

The notion of microsystems is based on the existence of projections of body segments and internal organs in a sectional area of the skin, mucous membrane, or periosteum, constituting somatotopies. For the Chinese medicine, when accessing specific points in these regions, it is possible directly influence all the individual's energy, promoting changes in the patient's physiology, pathophysiology, and symptomatology. The therapeutic efficacy of this technique is well established and has been shown to be equivalent to that of the traditional Chinese acupuncture for treatment of pain. There are many microsystems located in specific regions of the body, such as auricles, scalp and hands, for example.11,12

The nasal microsystem and the cranial suture microsystem13 were developed by the Professor and Head of Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine at the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) – Escola Paulista de Medicina (EPM), Dr. Ysao Yamamura.

Material and methodStudy design and contextThis study is a controlled clinical trial with 26 participants undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery (ACLR), who were recruited from the knee-group outpatient clinic of the Sports Medicine Discipline, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology at UNIFESP, São Paulo (SP), Brazil, from May 2018 to April 2019.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa – CEP) of UNIFESP, with CAAE number: 79249117.00003.5503, and all patients were required to read and sign the Free and Informed Consent Form (ICF). (Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido – TCLE).

ParticipantsThe selected participants underwent ACLR surgery at the Hospital Geral de Diadema, Diadema (SP), Brazil, and all met the following inclusion criteria: to be in the immediate postoperative period (first week) of ACL reconstruction surgery using a graft and semitendinosus tendon graft removal technique; present pain in the graft donor region (distal posteromedial region of the thigh); and be in the 18–50 age group.

The non-inclusion criteria were: absence of pain in the donor region; be unable to attend the treatment and evaluation center as often as necessary; having metabolic and/or rheumatological diseases; present signs and symptoms of lower limb neuropathy; and have lumbar radiculopathy and severe knee osteoarthritis.

The exclusion criteria were: use of opioid analgesics in the postoperative period; present surgery complications in the postoperative period (for example: graft rupture, infections, residual instability and arthrofibrosis); miss the first clinical evaluation and the first acupuncture session; and being absent from more than one appointment for clinical evaluation and from more than one acupuncture session.

The sample calculation was based on works of interest to this study, carried out to evaluate the effect of acupuncture microsystems techniques, previously published.14–16

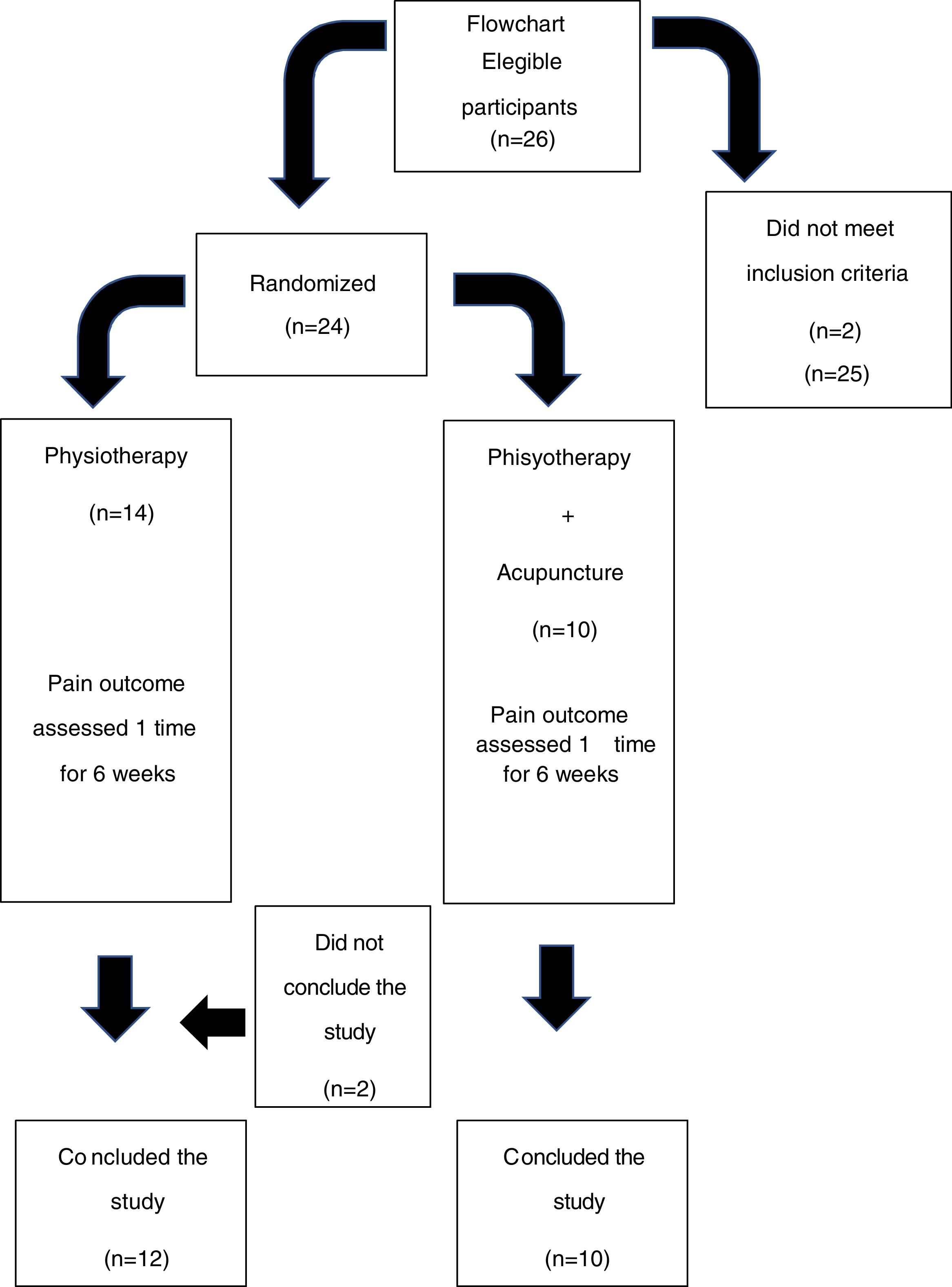

Participants, when attending the service for signing the informed consent form, were individually randomized, using the computer application Randomizer, by a subject not involved in the study, and thus allocated to one of the following groups: (1) physiotherapy group: patients treated with analgesic medication (dipyrone or paracetamol), non-hormonal anti-inflammatory, antibiotic and physical therapy (three times a week) for six weeks; and (2) physiotherapy and acupuncture group: patients treated with analgesic medication (dipyrone or paracetamol), non-hormonal anti-inflammatory, antibiotic, physical therapy (three times a week) for six weeks and 11 acupuncture sessions using nasal microsystem and cranial suture microsystem techniques once a week for the first week (fifth postoperative day (PO)) and twice a week from the second week to the sixth week (10°, 12°, 17°, 19°, 24°, 26°, 31°, 33°, 38° e 40° PO days). Two participants in group 1 were excluded from the study once they missed more than one return visit for pain assessment (Fig. 1).

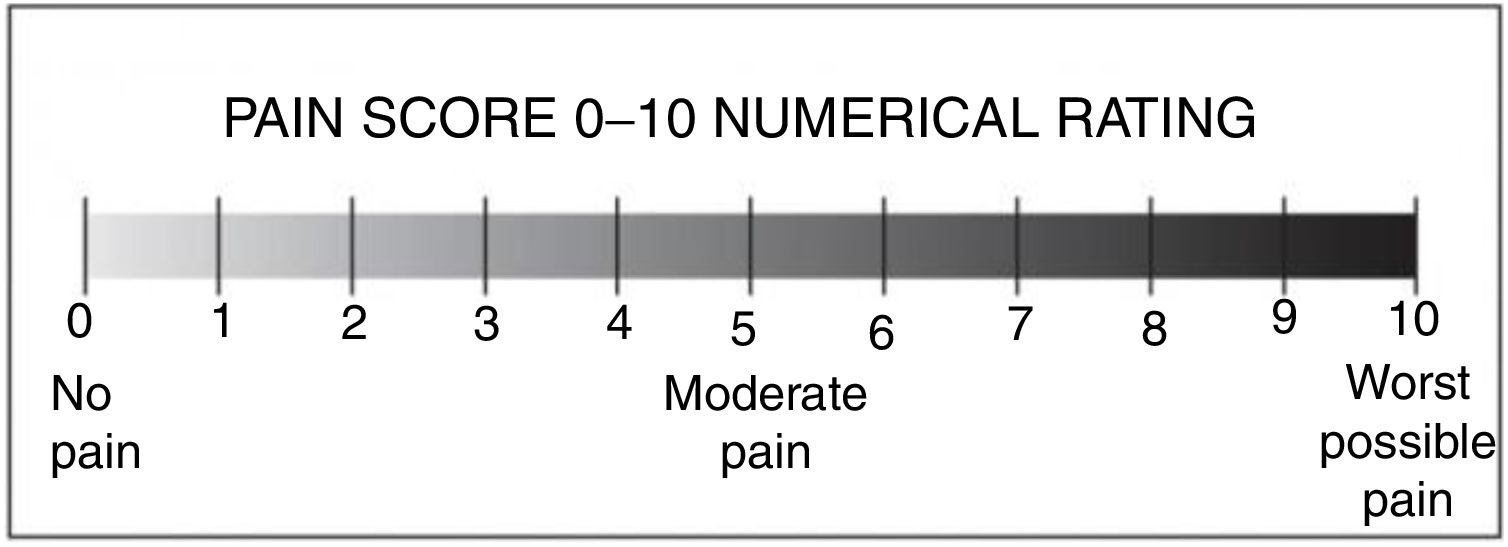

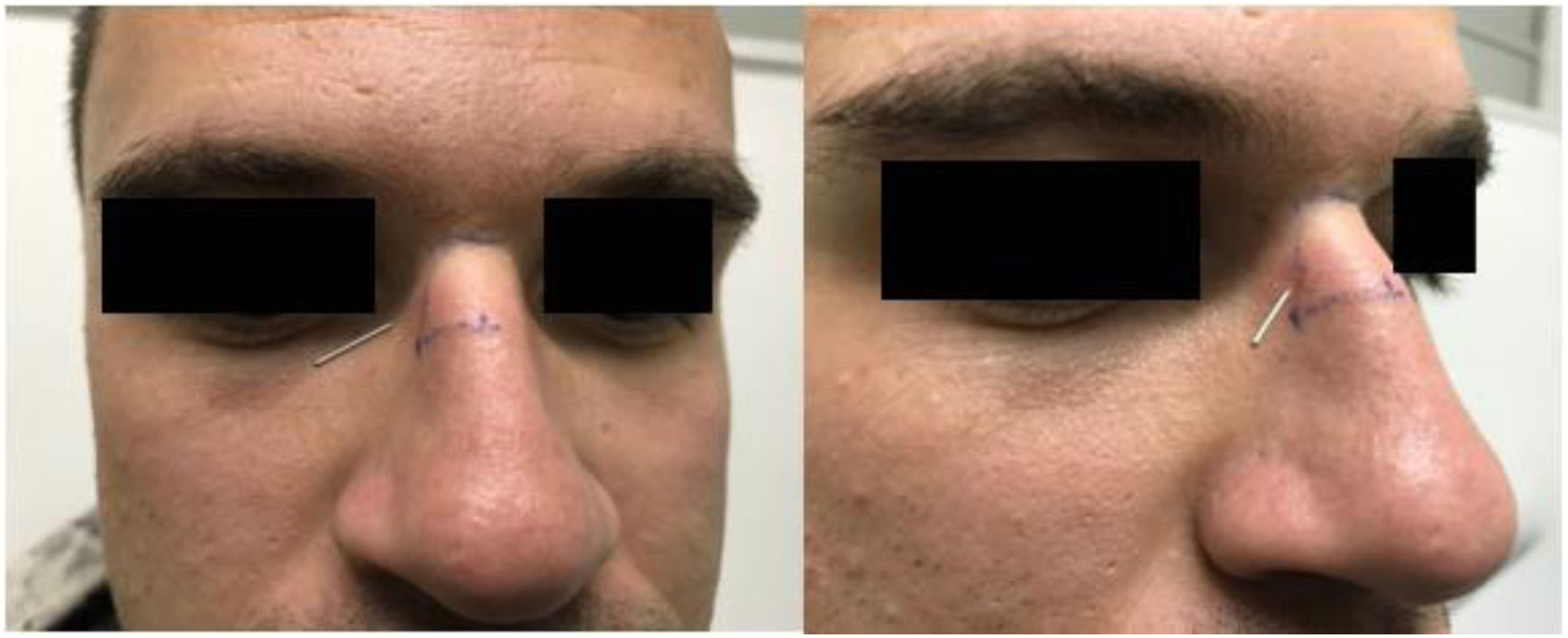

Clinical evaluationStudy participants attended the headquarters of the Discipline of Sports Medicine at UNIFESP during the first six weeks after surgery and were asked to rate the pain intensity in the distal posteromedial region of the graft donor thigh at 5, 12, 19, 26, 33 and 40 days, at the time of consultation for group 1 participants and before and after acupuncture sessions for group 2 participants. A plasticized table of the Numerical Pain Scale (NPS),17 offered at the time of evaluation by an independent examiner, was used for this purpose. It was emphasized to the participant, through guidance and demonstration, that it was essential to consider only pain in the medial and distal regions of the thigh (graft collection region), disregarding eventual joint pain (Figs. 2 and 3).

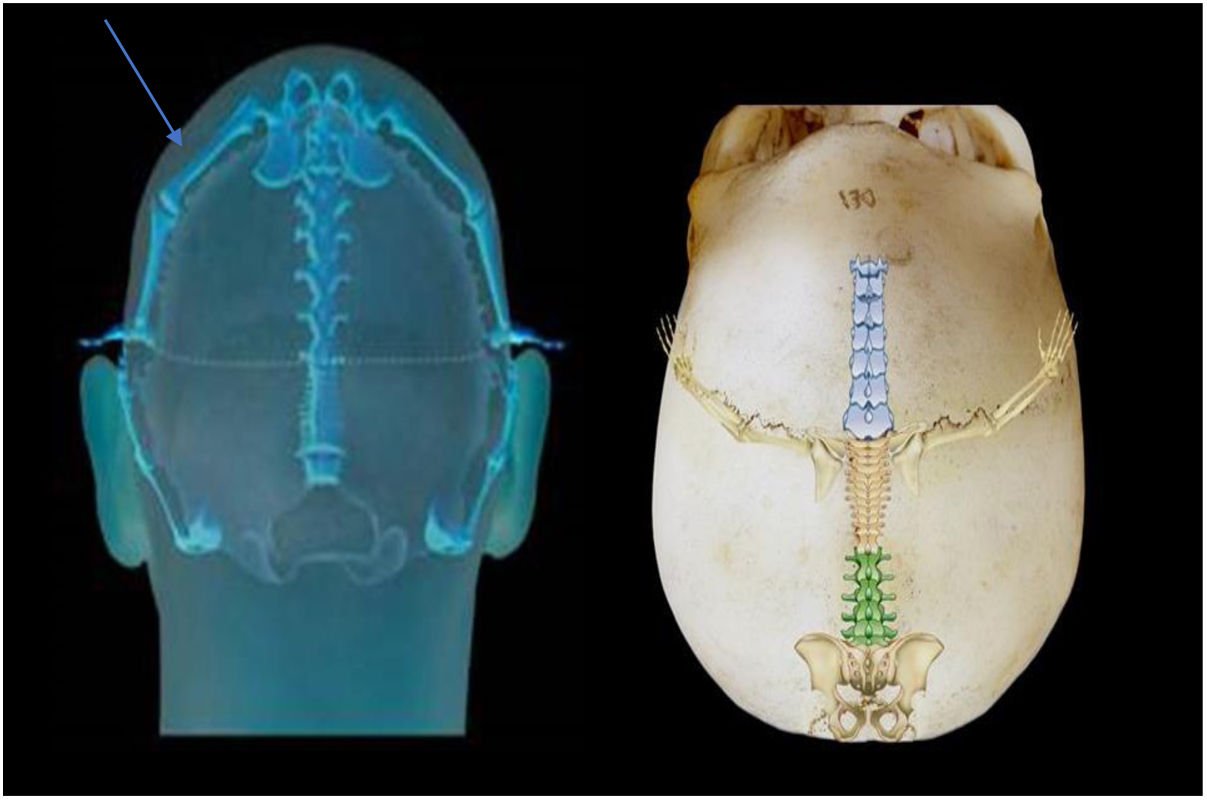

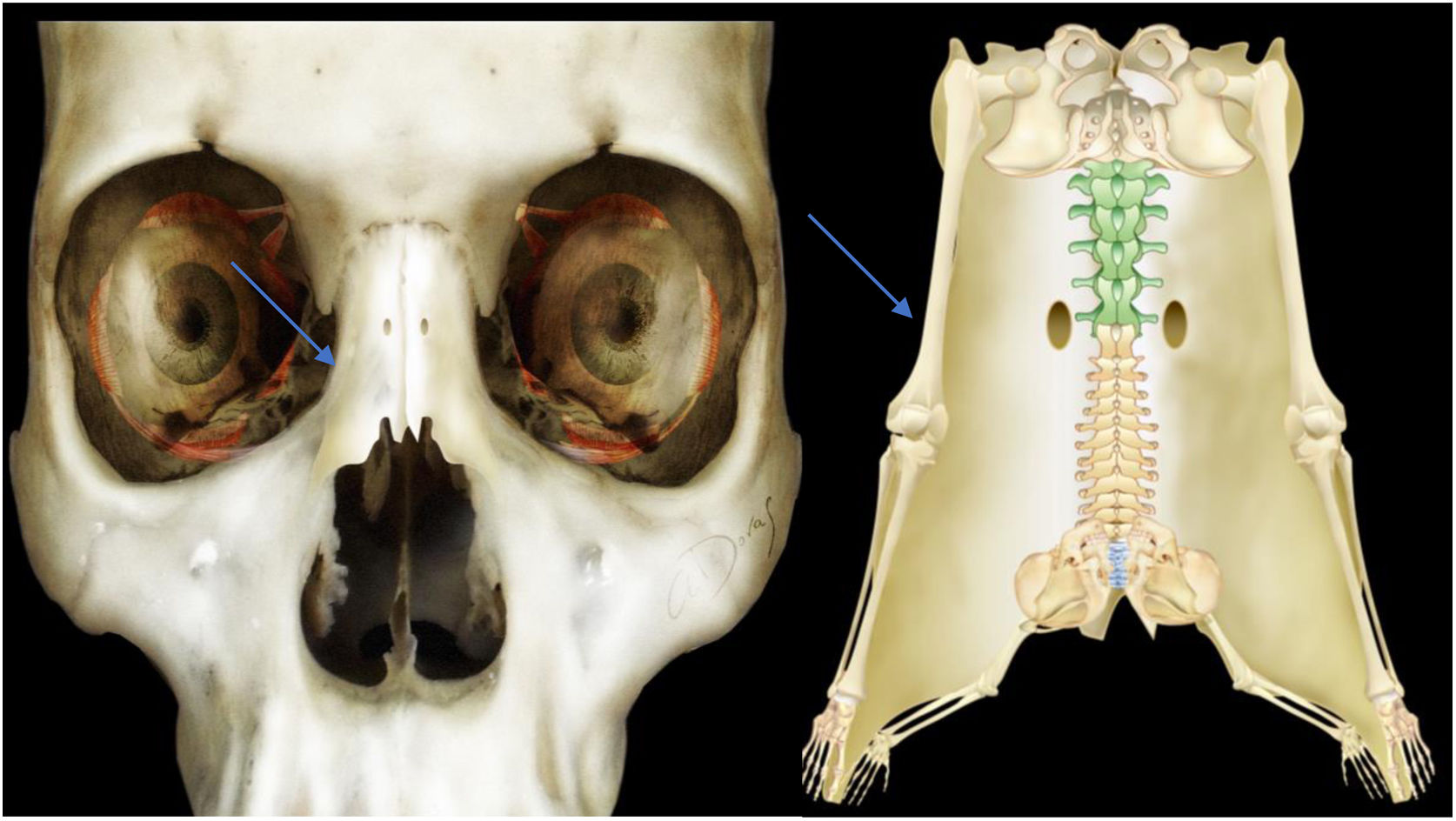

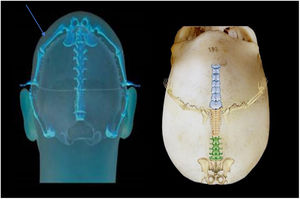

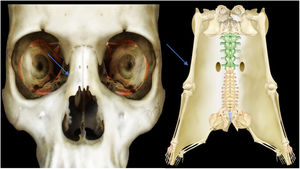

For acupuncture treatment, the cranial suture microsystem technique was performed in conjunction with the nasal microsystem technique, and all sessions were performed by the same medical professional specialized in acupuncture and with experience of more than five years of practice. All needles used were disposable stainless steel Dongbang brand, 0.20mm by 15mm and 0.18mm by 8mm, respectively. The method consists of inserting the needle in the somatotopic region of the cranial sutures (Figs. 4 and 5) and in the nasal bone (Figs. 6 and 7), corresponding to the area of the body to be treated. After locating the most sensitive point to palpation within the target region corresponding to the ipsilateral distal thigh in the microsystem of the cranial sutures, the needle was introduced up to the periosteum, looking for the point of greatest sensitivity at the site. After obtaining Te Qi (typical sensation caused by needling during an acupuncture session that can be characterized as acute pain, paresthesia, feeling of heaviness, shock or ill-defined sensation), patients were asked about the improvement or not of pain in the region where the graft was removed. If so, the needle was removed after five minutes. Otherwise, the procedure was repeated until the desired effect was achieved. The same technique was used to puncture the nasal microsystem, a procedure performed right after the first one (Figs. 6 and 7). It was not necessary to repeat the operation more than twice in any patient.

Physiotherapy treatmentThe rehabilitation treatment was individualized and performed by the physiotherapy team of the Discipline of Sports Medicine, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of UNIFESP. Physiotherapy started between three and five postoperative days, three times a week. Patients were instructed to use crutches and to unload weight on the affected limb according to tolerance. Cryotherapy was also indicated to manage pain and edema. Exercises for gaining range of articular movement, passive stretching of the posterior leg and thigh muscles, and isometric contraction of the quadriceps were taught and oriented to be performed at home. The objectives of rehabilitation were to maximize the patients’ response to the exercise indicated at each stage of the process, considering the level of functionality and to minimize the risk of additional injury to the healing tissues. The parameters for its application are based on the publication of scientific articles cited in the bibliography of this work.18,19

Statistical analysisIn the statistical analysis, the significance level of 0.05 is considered, which is equivalent to a 95% confidence.

Two tests were used: the Mann–Whitney's nonparametric, to compare the evolution of pain scores between groups, and Friedman's nonparametric, to analyze the evolution of pain scores in the groups individually during the follow-up.

To compare the pain scores measured before and immediately after the acupuncture session in participants of group 2, the paired t-Student test (95% Confidence Interval) was used.

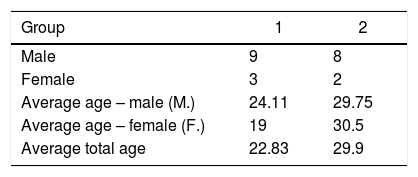

ResultsA total of 22 patients with ACLR completed the study, 17 men and 5 women, with ages ranging from 18 to 48 years, and a mean of 26.04 years. All were practitioners of professional or amateur sports activities. The results of the participants’ characteristics can be better observed in Table 1.

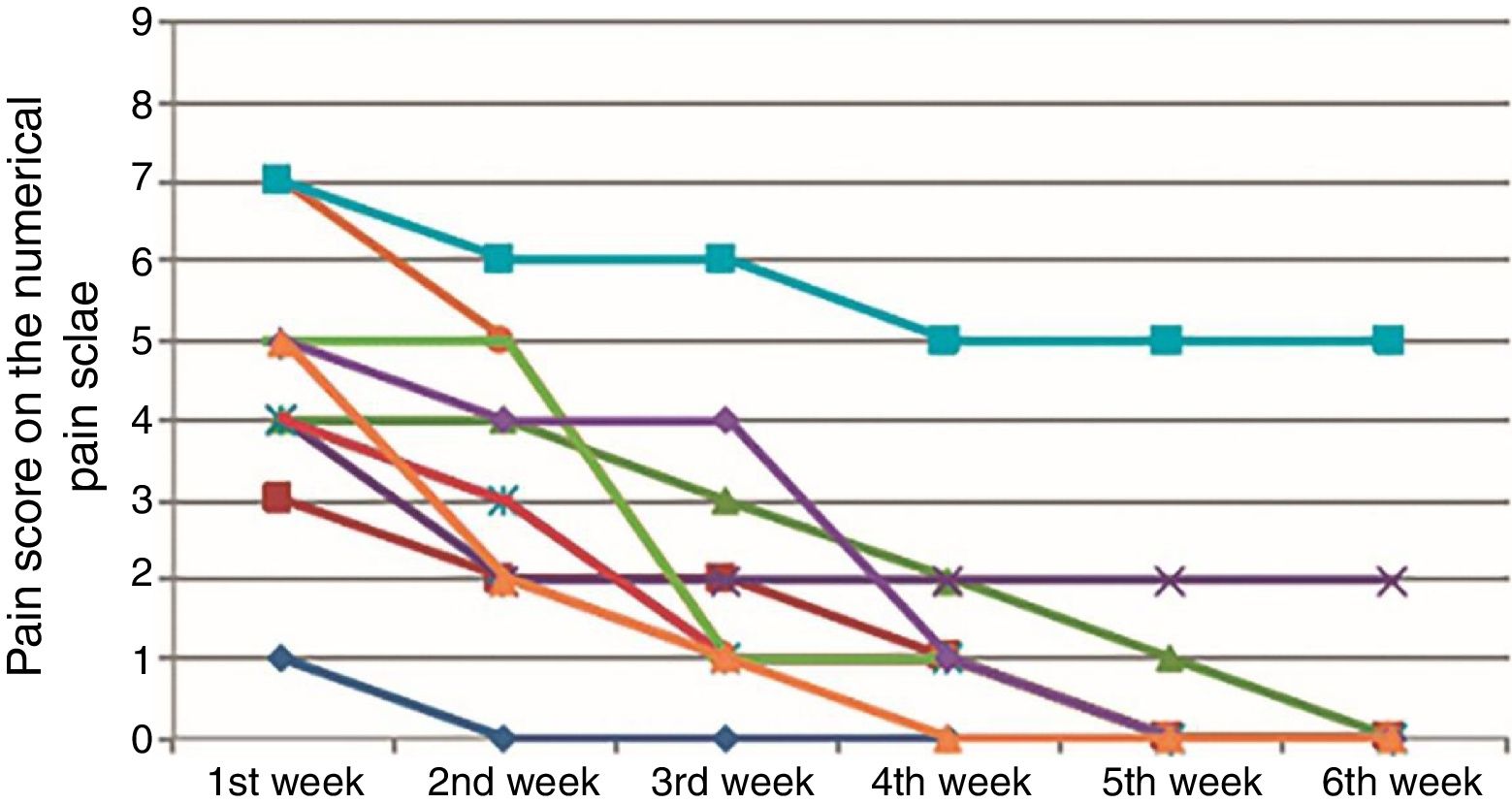

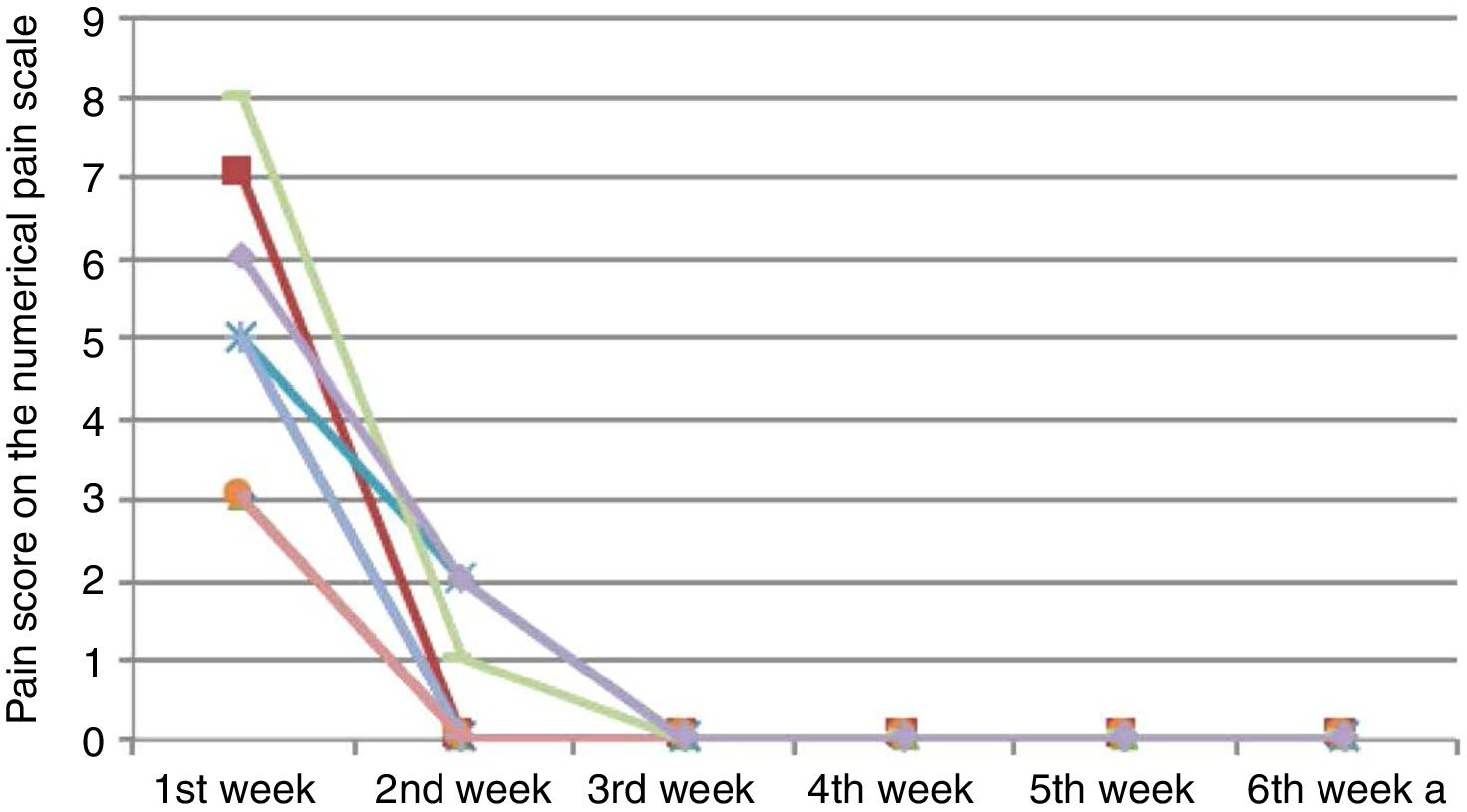

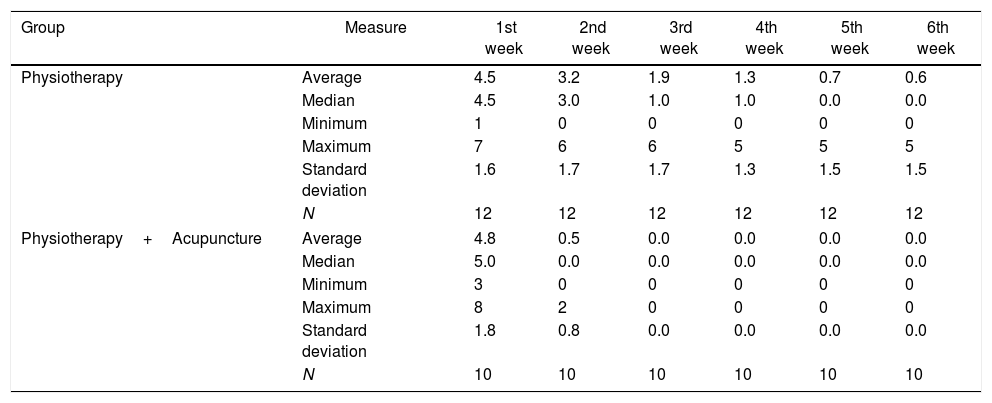

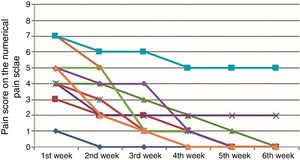

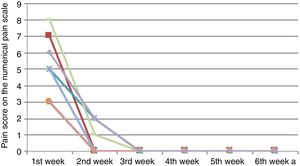

Figs. 8 and 9 show the evolution of pain scores over the weeks in groups 1 and 2, respectively. In group 1, it was observed that the reduction occurred gradually, while in group 2 it was accentuated in the second week.

In group 2, it was observed that all patients had a zero score from the third week evaluation, indicating absence of pain. In group 1, however, scores greater than zero were observed until the end of the follow-up.

Table 2 shows the evolution of pain scores during follow-up, according to treatment group. It is important to note that the means and medians in the control group gradually decreased. In the intervention group, however, there was an abrupt decrease from the first to the second week.

Pain scores on the Numerical Pain Scale (NPS) of patients undergoing ACL reconstruction with semitendinosus and gracile tendon grafts, according to treatment group.

| Group | Measure | 1st week | 2nd week | 3rd week | 4th week | 5th week | 6th week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiotherapy | Average | 4.5 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Median | 4.5 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Minimum | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Standard deviation | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| N | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | |

| Physiotherapy+Acupuncture | Average | 4.8 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Median | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Minimum | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Standard deviation | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| N | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

In comparing both groups at each moment (Table 2), the Mann–Whitney test was performed, and the following p-values were obtained, demonstrating a significant difference between the groups only at weeks 2, 3 and 4:

- •

Week 1: U=63, p-value=0.839.

- •

Week 2: U=10.5, p-value=0.001.

- •

Week 3: U=5, p-value<0.001.

- •

Week 4: U=10, p-value<0.001.

- •

Week 5: U=45, p-value=0.098.

- •

Week 6: U=50, p-value=0.186.

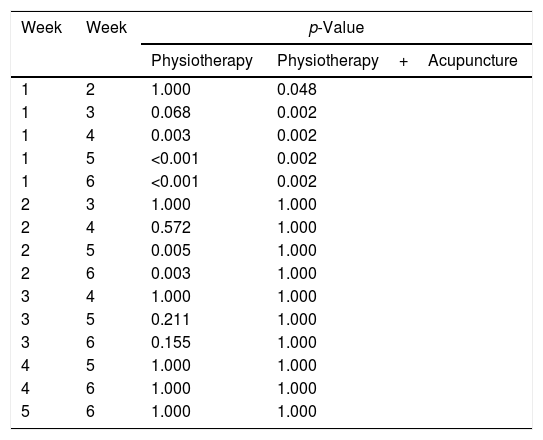

Table 3 shows the results of multiple comparisons between weeks for the two groups, based on the Friedman test. The analysis results show the following:

- •

Physiotherapy group (1)

- •

Week 1: different from weeks 4, 5 and 6.

- •

Week 2: different from weeks 5 and 6.

- •

Weeks 3, 4, 5, and 6: no significant differences.

- •

- •

Physiotherapy+acupuncture group (2)

- •

Week 1: different from weeks 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

- •

Weeks 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6: no significant differences.

- •

Results of multiple comparisons between weeks in both groups by the Friedman test.

| Week | Week | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiotherapy | Physiotherapy+Acupuncture | ||

| 1 | 2 | 1.000 | 0.048 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.068 | 0.002 |

| 1 | 4 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| 1 | 5 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| 1 | 6 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| 2 | 3 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 2 | 4 | 0.572 | 1.000 |

| 2 | 5 | 0.005 | 1.000 |

| 2 | 6 | 0.003 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 4 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 5 | 0.211 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 6 | 0.155 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 5 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 4 | 6 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 5 | 6 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

In group 2, the pain assessment was performed before and after acupuncture sessions. When comparing the scores in these two assessments performed in the first week, a significant reduction was observed (p<0.001). In the pre-session assessment, pain scores ranged between 3 and 8 points, with a mean of 4.8 (SD=1.8) and, in the post-session assessment, they ranged between 0 and 2 points, with a mean of 0, 9 (SD=0.9), representing an average reduction of 3.9 points (95% CI: 3.0–4.8 points).

DiscussionThe present study aimed to evaluate the effect of adding the acupuncture techniques of nasal microsystem and cranial suture microsystem to the rehabilitation treatment established in the thigh muscle pain of patients undergoing RLCA with graft from tendons of the semitendinosus and gracile muscles and, as a main result, it showed that the reduction in pain score occurred in both groups throughout the treatment. However, in group 1, the reduction was gradual, while in group 2 there was a marked improvement already in the second week.

Patients who received treatment with acupuncture reported a pain score equal to zero from the third week onwards and presented immediate relief of pain in the medial and distal thighs in the first session. Some patients in the group not treated with acupuncture experienced pain until the last week of evaluation.

The present study results suggest that nasal microsystem and cranial suture microsystem techniques, when used together for treatment of pain related to muscle injuries caused in these circumstances, were able to improve analgesia, helping in the management of the patient in the post-early surgery, facilitating rehabilitation and promoting greater comfort for carrying out daily activities.

The techniques under study were developed by the professor and head of the Discipline of Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine of the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of UNIFESP-EPM, Prof. Dr. Ysao Yamamura, and have been used for more than four years in the Acupuncture Emergency Service at Hospital São Paulo. The application of these microsystems, in a joint or isolated manner, to treat peripheral pain in this service was found in more than a thousand visits from March 2017 to August 2019, showing a percentage of improvement in pain score assessed by the Visual Analog Scale, before and immediately after the session, varying between 50% and 100%.13

There are microsystems in different regions of the body, which have been presented in studies that prove their effectiveness for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain.16–25 However, until now, there are no publications on the described techniques, which are characterized by practicality and effectiveness, providing instant relief from the pain symptom, constituting an economic resource with few potential side effects and exempt from violating anti-doping legislation in case they are applied in athletes.

Regarding other therapies used for acute or chronic muscle pain, it was observed that, in the work carried out by Correia et al., 2015,16 20 patients with chronic myofascial pain in cephalic and cervical regions were treated with the YNSA acupuncture microsystem technique for eight weeks (once a week). Regarding this last aspect, the results with a gradual reduction in pain scores every week of evaluation and with immediate relief after needle insertion in 100% of the cases were similar to those of the present study.

In 2015, Ferreira et al. studied the effect of adding treatment with auricular microsystem acupuncture to splint (orthosis) treatment for myofascial pain in the masticatory muscles and for temporomandibular joint pain. They observed that, although the two groups showed a statistically significant reduction in pain scores over the course of the follow-up, when comparing them, the group of the study showed a significant improvement in the first week. In that work, the description of the treatment technique included the simultaneous use of several needles and their maintenance in the pinna for five days.15

Considering possible action mechanisms of the nasal microsystem and cranial suture microsystem, it is known that the trigeminal nerve, the fifth cranial pair, has three major branches distributed over the face: the ophthalmic, jaw and mandibular nerves. The external region of the nose is innervated by the external nasal nerve, branch of the ophthalmic nerve. The three branches of the trigeminal nerve converge to the trigeminal ganglion, located in the Meckel trigeminal cavity, whose first order neurons project to the trigeminal nuclei in the brainstem region. These structures have extensive connections with the limbic system and local monoaminergic nuclei.26–28

The scalp region, in the parietooccipital transition, is innervated by the greater occipital nerve, which is a branch of afferent roots at levels C2 and C3 of the spinal cord.29

There is integration between the trigeminal nuclei, the solitary tract of the vagus nerve and the branches of C1, C2 and C3 cervical roots. It is known that the impulses from this system are capable of activating the periaqueductal gray zone and the nuclei involved in the descending pain control mechanism, in addition to modulating the activity of limbic system structures, thalamus, hypothalamus and somatosensory cortex, modulating the central processing of the nociceptive impulse.27–29

Experiments and clinical observations have shown that the brain and the immune system form a network with bidirectional signaling and communicate via specific neuronal and humoral pathways. It is well known and established that the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is stimulated by acupuncture with increased corticosteroid release.9 Evidence suggests the existence of a negative feedback loop between the autonomic nervous system and the innate immune system. The vagus nerve stimulation was able to inhibit macrophage activation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines through what is known as the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.4 This concept opens the way for a better understanding of the systemic and localized anti-inflammatory effects that acupuncture can provide.

In the light of scientific knowledge already produced so far, it is possible to understand the analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of acupuncture as the result of the neuromodulation process and activation of neurological reflexes. Much remains to be elucidated in relation to its mechanism of action, and other scientific works must be produced for this purpose.

Study limitationsPossibility of bias regarding the evaluation of thigh pain in the graft collection region (irradiated joint pain, injury to the saphenous nerve or its branches). It is intended to avoid this occurrence, emphasizing the orientation regarding the location and type of pain studied.

The daily medication reminder was not carried out as recommended by the CONSORT 2010 Statement.30

Randomization did not follow the standard recommended by the CONSORT 2010 Statement.30

The absence of a control group with sham acupuncture in this study is one of its limitations and is due to the technical difficulty of devising a procedure that reliably simulates needling. There are disagreements regarding the location of some points and many of them are not cataloged. Evidences suggest that sham acupuncture has an intermediate effect between the actual procedure and placebo, since the puncture of any region has a biological effect.11

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest.