Pneumocystis jirovecii colonization rates in healthy patients are unclear. Previously published studies suggest that the fungus could play a role in the physiopathology and progression of chronic respiratory diseases.

AimsThe goal of this study was to determine the prevalence of colonization by this fungus in the lower respiratory tract of immunocompetent patients who are not at risk of dysbiosis.

MethodsThe presence of P. jirovecii was confirmed in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from adults who underwent bronchoscopy for non-infectious reasons, had no immunosuppressive factors, and had not been on antibiotic treatment for at least one month. The results were compared with those obtained in the study on the presence of Pneumocystis in environmental dust samples obtained by swabbing surfaces in the participating subjects’ domestic settings. Real-time PCR was the technique used for detecting the fungus in both types of samples.

ResultsA total of 97 BAL samples and 49 domestic environment samples were studied. The medical reasons for needing a bronchoscopy were, mainly, the examination of both pulmonary neoplasm in 55 patients (57%) and diffuse interstitial lung disease in 21 patients (22%). The overall prevalence of P. jirovecii in our population was 7.22% in BAL samples and 0% in domestic samples.

ConclusionsThe presence of P. jirovecii in the lower respiratory tract is relevantly linked with the patient's immune status, not with an underlying pathology. Prevalence is low in immunocompetent individuals who do not have any infectious pathology and are not having antimicrobial treatments. Our results do not enable us to figure out which the environmental niche of P. jirovecii is.

Las tasas de colonización de Pneumocystis jirovecii en los pacientes sanos no están claras. Estudios previos sugieren que este hongo podría desempeñar un papel en la fisiopatología y en la progresión de enfermedades respiratorias crónicas.

ObjetivosEl objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la prevalencia de colonización por Pneumocystis en el tracto respiratorio inferior de los pacientes inmunocompetentes y sin riesgo de disbiosis.

MétodosLa presencia de P. jirovecii fue confirmada en muestras de lavado broncoalveolar (LBA) de adultos que se sometieron a una broncoscopia por causa no infecciosa, sin factores de inmunodepresión y que no hubiesen recibido tratamiento antibiótico al menos el mes previo. Los resultados se compararon con aquellos sobre la presencia de Pneumocystis en muestras de polvo de ambiente y superficies del entorno doméstico de los sujetos participantes. Para la detección en ambos tipos de muestras se utilizó PCR en tiempo real.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 97 muestras de LBA y 49 muestras del entorno doméstico. Las indicaciones para la broncoscopia fueron principalmente estudio de neoplasia pulmonar en 55 pacientes (57%) y enfermedad pulmonar intersticial difusa en 21 pacientes (22%). La prevalencia total de P. jirovecii en nuestra población fue del 7,22% en las muestras de LBA y del 0% en las muestras domésticas.

ConclusionesLa presencia de P. jirovecii en el tracto respiratorio inferior está principalmente relacionada con el estado inmunológico del paciente, en lugar de con una enfermedad subyacente. La prevalencia en individuos inmunocompetentes, sin enfermedad infecciosa y sin tratamiento antimicrobiano reciente, es baja. Nuestros resultados no permiten dilucidar cuál es el nicho ambiental de P. jirovecii.

Pneumocystis jirovecii is an opportunistic fungus that frequently affects patients with Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) or patients who are immunodepressed for other reasons, causing a pneumonia (Pneumocystis pneumonia) that has a high rate of associated morbidity-mortality.10,41,43P. jirovecii is a ubiquitous, extracellular and single-celled fungus considered atypical because of the difficulty in get it grown in culture,6,36 and the lack of ergosterol in its plasma membrane, which makes it insensitive to many antifungal agents.13 The species P. jirovecii is considered a human host-specific fungus, and displays a particular tropism for the lung; the fungus has been found in the alveolar spaces.8,18 However, extrapulmonary Pneumocystis infections have been documented.29,40 Its transmission mechanisms are not thoroughly known, and although the environmental niche of the fungus has not been determined, it has been isolated from air samples taken from rooms or homes of patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia or immunosuppressed patients.2,19 There is sufficient evidence to confirm the fungus enters the organism by the airborne route, and the most likely mean of transmission is person-to-person, but the question of whether its entry in the host could take place from environmental sources is still open.6,8,45,47

Only few studies on the presence of colonization of this pathogen in healthy patients have been conducted due to ethical grounds which prevent from acquiring lower respiratory tract samples from these individuals. There are two notable studies in the literature that were specifically designed to evaluate the prevalence of P. jirovecii in the general population. In one of them, oropharyngeal washes were tested, and P. jirovecii was found in 12 participants out of 50.21 The second one analyzed sputum samples, and no positive result was obtained from any of the 30 healthy subjects under study.27 There are other studies in which the prevalence in health care professionals12 and pregnant women43 was evaluated, showing widely varying colonization rates (from 2.5% to 40.5%). Most of the studies that have analyzed the prevalence of P. jirovecii colonization involved patients meeting immunosuppression criteria, especially those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, in whom prevalence rates ranging from 46% up to 68% were found.10 This also applies to patients with chronic lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),4,5,15,23,25 cystic fibrosis,3,22,28,32,37,44 or interstitial lung diseases (ILD).26,30,38,46 Studies performed on COPD patient populations have shown that colonization by Pneumocystis is associated with greater severity of the disease,23 related with increased systemic inflammatory response.5 As for its relationship with lung carcinoma, there are studies that investigated P. jirovecii colonization in relation to the different stages of the disease;1,14,17,38,39,48 in some others studies concerning colonization, autopsies were performed,11,31 and widely variable colonization rates were described.

Despite the knowledge acquired up to now, the role of P. jirovecii colonization in lung physiology and pathology is still unclear. Aspects such as its relationship with other lower respiratory tract colonizers, and the possible alteration of this microbiome (dysbiosis), have not yet been explored. There are very few studies that describe the pulmonary mycobiome in immunocompetent individuals due to the aforementioned limitations. Furthermore, these studies are usually performed using internal transcribed spacers (ITS) of ribosomal RNA as universal fungal targets. This is something of a handicap in the detection of P. jirovecii due to the lower sensitivity of the method with this fungus:9,16,33,35Pneumocystis has few copies of these genes. Therefore, it is recommended to use other specific targets for its identification. The mitochondrial large subunit ribosomal RNA (mtLSU rRNA) is the most widely used.34

Our study is included within a project on lung mycobiome characterization in immunocompetent patients without dysbiosis risk factors. The aim of the study is to determine the presence of P. jirovecii as part of the lower respiratory tract microbiome in these individuals, and determine whether the fungus is present in the domestic environments of the colonized patients.

Material and methodsThis is a multicentre, prospective observational study, carried out between 2015 and 2023 in four university hospitals in Alicante province (Elda General University Hospital, Alicante General University Hospital (Dr. Balmis Hospital)–, Vinalopó University Hospital, and San Juan de Alicante University Hospital).

Patient recruitment was made with the following inclusion criteria: adult patients who met criteria for bronchoscopy, who agreed to take part in the study, and signed an informed consent document. The exclusion criteria were being at risk of dysbiosis due to active infection and/or being on antibiotic or cytotoxic treatments for at least four weeks prior to the examination; and having immunosuppression according to the following criteria: Neutropenia (<500cells/mm3) for more than 10 days in the previous month; prolonged steroid treatment (>20mg/day for more than 3 weeks, or >700mg total prednisone or similar in the previous two months); immunosuppressant therapy in the previous three months; solid organ transplant recipient; haematopoietic transplant recipient; haematologic neoplasm in the previous year; chemotherapy in the previous six months; and hypogammaglobulinemia.

BAL samples were collected from the patients and domestic dust samples from their homes. Bronchoscopy control samples from different participating hospitals were also collected. Demographic and clinical data, such as age, gender, profession, smoking status and the diagnosis supporting the bronchoscopy, were gathered with each patient. The study received the approval from the ethical committee of all participating hospitals, as well as the one from Miguel Hernández University. The ethical standards laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki were always followed.

BAL sampling by bronchoscopyBronchoscopies were performed using conscious sedation, and premedicating the patient with midazolam (5mg/mL) and fentanyl (0.05mg/mL) intravenously, at the clinician performing the procedure own discretion. After the sedation, lidocaine solution 2%, or lidocaine spray at 4% or 10%, were used in the nose and upper respiratory tract and trachea by means of the “spray-as-you-go” technique. Aspiration in the upper respiratory tract was prevented. The BAL was preferentially performed in the middle lobe. If that was not possible, it was performed in the lingula. Aliquots of 20 or 50mL of sterile saline solution (NaCl 0.9%) were instilled (maximum 150–200mL), discarding the first aliquot, and processing the second one. Immediately afterwards, the samples were transported in refrigerated conditions to the biobank of the Alicante General University Hospital. At the biobank, N-acetylcysteine 10% was added, and the samples were divided into aliquots of 1–1.5mL. The aliquots not immediately processed were kept in the biobank at −80°C.

Environmental samplingSamples were taken consecutively throughout the years of the study in 16 different municipalities of Alicante province. In the homes, dust was taken from surfaces using swabs previously doused in aqueous solution with 0.05g/L of chloramphenicol to inhibit bacterial overgrowth. The swabs were rubbed against the surfaces of every room (furniture, walls, air conditioning units, shelves, hobs, pet beds, leaves and stems of house plants, and others). In order to properly transport them to the laboratory, they were sheathed by being placed in 2mL of chloramphenicol solution. At the laboratory, the content of each swab was vigorously shaken and then transferred to a microtube. From each of the microtubes 100μL were extracted. These liquid extractions were then mixed together into a single home sample (ENV sample) with each patient. These samples were centrifuged, and the DNA from the pellet was extracted to find P. jirovecii.

Bronchoscopy controlsIn order to ensure the sterility of the procedure and control the potential introduction of biota through the instruments used for sample collection, random checks of the bronchoscopes employed for sampling were performed in the participating hospitals. In each control checking, a wash sample from the equipment was obtained at the time it was ready for use. Saline solution (100mL) was poured into the working canal of each bronchoscope, collecting the wash fluid in a conventional sterile sample collection container. This material was labelled as an additional sample and subjected to the same treatment and analysis as the samples obtained from the patients.

Molecular biology techniquesDNA was extracted from the samples using the Blood&Tissue commercial kit from Qiagen®. The DNA concentration was measured with the Qbit® fluorometric system, setting the minimum amount of quality in 0.5ng/μL of DNA. The detection of P. jirovecii was performed with a real-time PCR (qPCR) using CerTest VIASURE Pneumocystis jirovecii Real Time PCR kit (CerTest BIOTEC), and following the manufacturer's instructions. This commercial kit bases the identification of P. jirovecii on the amplification of a conserved region of the mitochondrial large subunit in the ribosomal RNA (mtLSU rRNA).

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed with the programme SPSS24 (SPSS, IBM Corp.) and with R (The R Project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/), considering a value of p<0.05 statistically significant. For the descriptive analysis, the qualitative variables were expressed in absolute numbers and percentages, and the quantitative variables as mean values±standard deviation. The comparison of proportions (sex, smoking background, underlying disease) was performed through the binomial exact test and Fisher's exact test. Student's t-test was performed to compare the means from independent groups (age).

ResultsA total of 97 patients were recruited, of whom 49 (50.51%) agreed to have their homes sampled. The homes were located in 16 different municipalities of Alicante province (southeast Spain, EU). BAL samples from the 97 patients and 49 samples gathered from patients’ homes were analyzed. In addition, four bronchoscopy controls were obtained and analyzed.

The demographic variables of the population studied were the following: 56 male patients (57.7%) with a mean age of 64±10.39 years. Patients’ professions varied widely, covering 39 different declared occupations, of which the most frequent were office worker and footwear industry worker, with 14 individuals each (14,43%), followed by employees in construction, 13 individuals (13.40%). Regarding smoking status, 41 (42.3%) of the patients recruited claimed to be active smokers; 29 (29.9%) were ex-smokers and 27 (27.8%) were non-smokers. The average consumption of tobacco in our population was 43 packs of cigarettes per year. The underlying diseases, or presumptive diagnoses, supporting the bronchoscopy are shown in Table 1, with the most frequent causes being the study of pulmonary neoplasm in 55 patients (56.7%) and ILD in 21 patients (21.6%). Adenocarcinoma was the most frequent histological type of neoplasm, being detected in 23 patients (41.8%), followed by squamous-cell carcinoma in 13 patients (23.6%) and small-cell carcinoma in 11 patients (20%).

Detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii (bronchoscopy) in relation to patients clinical findings.

| Diagnosis and clinical manifestations | N | % | P. jirovecii in BALa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 55 | 56.7% | 4 (4.1%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 23 | 41.81% | 2 (3.6%) |

| Cutaneous squamous-cell | 13 | 23.63% | 1 (1.8%) |

| Small-cell | 11 | 20% | 0 (0%) |

| Undifferentiated | 1 | 1.81%% | 0 (0%) |

| Metastasis | 2 | 3.63% | 0 (0%) |

| Neuroendocrine | 1 | 1.81% | 1 (1.8%) |

| Other | 4 | 7.27% | 0 (0%) |

| ILDb | 21 | 21.6% | 1 (1%) |

| Haemoptysis | 6 | 6.2% | 1 (1%) |

| Benign lung nodule | 3 | 3.1% | 0 |

| Tuberculosis sequels | 2 | 2.1% | 0 |

| Cough | 2 | 2.1% | 0 |

| Tracheal stenosis | 2 | 2.1% | 0 |

| COPDc | 1 | 1% | 0 |

| Endobronchial foreign body | 1 | 1% | 1 (1%) |

| Other (dyspnoea, atelectasis, bronchiectasis) | 4 | 4.12% | 0 |

| Total | 97 | 100% | 7 (7.22%) |

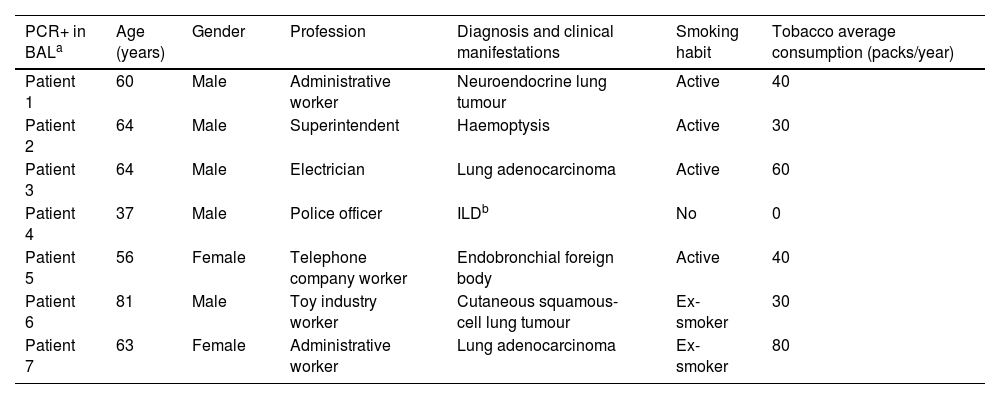

Pneumocystis was detected in the BAL of seven patients (7.22%). Cancer was the group of greatest prevalence, with four out of 55 (7.27%) patients having a positive PCR. Within this group, adenocarcinoma was the type of tumour with the highest prevalence of colonization by P. jirovecii (two patients, 3.6%), followed by squamous-cell carcinoma, and neuroendocrine carcinoma, one patient each (1.8%) (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the seven patients in whom P. jirovecii was detected are outlined in Table 2. The distribution of patients with P. jirovecii colonization in relation to gender and smoking habit is shown in Fig. 2.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with a positive PCR test for Pneumocystis jirovecii.

| PCR+ in BALa | Age (years) | Gender | Profession | Diagnosis and clinical manifestations | Smoking habit | Tobacco average consumption (packs/year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 60 | Male | Administrative worker | Neuroendocrine lung tumour | Active | 40 |

| Patient 2 | 64 | Male | Superintendent | Haemoptysis | Active | 30 |

| Patient 3 | 64 | Male | Electrician | Lung adenocarcinoma | Active | 60 |

| Patient 4 | 37 | Male | Police officer | ILDb | No | 0 |

| Patient 5 | 56 | Female | Telephone company worker | Endobronchial foreign body | Active | 40 |

| Patient 6 | 81 | Male | Toy industry worker | Cutaneous squamous-cell lung tumour | Ex-smoker | 30 |

| Patient 7 | 63 | Female | Administrative worker | Lung adenocarcinoma | Ex-smoker | 80 |

Regarding the environmental samples, five of the seven patients in whom P. jirovecii was detected in the BAL (71.4%) had allowed to get their homes sampled. The result was negative in all the samples studied (100%). In the same way, the result was negative in all bronchoscopy controls.

No statistically significant relationship was found between the detection of P. jirovecii and any of the demographic or clinical parameters considered (Table 3).

Study of statistical dependence between positive PCR test for Pneumocystis jirovecii and each of the other variables.

| Variables analyzed | PCR+ | PCR− | Statistical test | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 5 (71.43%) | 51(56.66%) | Binomial exact test | 0.22 |

| Female | 2 (28.57%) | 39 (43.33%) | ||

| Age | 60.71±13.06 years | 63.95±10.63 years | T-student | 0.446 |

| Smoking habit | 6 (85.71%) | 64 (71.11%) | Fisher's exact test | 0.669 |

| Underlying disease | ||||

| Lung cancer | 4 (57.14%) | 51 (56.66%) | Fisher's exact test | 1.0 |

| ILDa | 1 (14.28%) | 20 (22.22%) | 1.0 | |

| Haemoptysis | 1 (14.28%) | 5 (5.55%) | 0.72 | |

| Endobronchial foreign body | 1 (14.28%) | 0 (0%) | 0.370 | |

The results in this study support the theories previously put forth by other authors regarding a lower prevalence of P. jirovecii colonization in immunocompetent individuals. Our study has been carried out on a population recruited on the basis of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. As a result, it can be stated that the samples analyzed were taken from individuals who, although not considered healthy properly speaking, were not immunosuppressed, and not subjected to situations that might cause dysbiosis, such as infectious processes, or were having antimicrobial or cytotoxic therapy. In fact, our results show a low rate of colonization by P. jirovecii (7.22%). The rate is lower than that described in previous studies with populations that presented similar underlying diseases, such as bronchogenic cancer, diffuse ILD and COPD.23,38,46 For example, prevalence rates ranging from 0% up to 100% have been described among patients with cancer,11,42 including some moderately high prevalence values (20.9% and 17.9%).38,48 This large variability makes it impossible to establish any type of positive or negative relationship between pulmonary carcinoma and colonization by P. jirovecii. We believe that, in order to assess this possible relationship, it is essential to consider both the tumour stage and whether the patient is undergoing any cancer treatment that may cause a significant immunosuppression. We are aware of the existence of immune-evasion mechanisms during the development of the tumour. Tumour cells in the immune-escape phase can cause an immunosuppressive state within the tumour microenvironment.7 However, consider oncology patients as overall immunosuppressed individuals at the time of diagnosis is controversial, as multiple factors, especially oncologic treatments, have an important impact on the immune status.

As previously stated, our study included patients with lung cancer at the time of their diagnosis. None of them had received any oncologic treatment. For this reason, although we did not check the immune status of patients specifically (e.g. by peripheral CD4 cell count), we considered our population as immunocompetent. The same reason may be the cause of the lower prevalence of P. jirovecii colonization found in comparison with other studies on cancer patients.

There is little information published regarding ILD, but a study by Vidal et al.,46 in which the colonization prevalence data reached 33.8% (27 out of 80 patients), is worth noting. Although these authors excluded patients who had immunosuppressant treatment, others suffering from active inflammatory and infectious processes (granulomatosis and pulmonary aspergillosis, among others) that induce dysbiosis in the microbiome were included, which may explain the higher colonization found.

According to our results, P. jirovecii colonization is not related with the underlying disease per se, as we did not find in our patients significant differences between the health condition and the detection of P. jirovecii. The higher positive detection rate was found among oncologic patients with bronchogenic carcinoma, especially in those diagnosed with the adenocarcinoma type. That group was the largest in the study, and the prevalence found in our series coincides with the values accepted for the general population.48 In the study by De la Horra et al.11 the prevalence of P. jirovecii found in the autopsies of patients who had died from small-cell carcinoma was 100%. Our population included 11 patients diagnosed with this disease, but none of them presented colonization by this fungus. We believe that this difference is basically due to the very different underlying health status between both groups of patients, even though the patients may have the same oncologic diagnosis in terms of cancer type. De la Horra group comprehended oncologic patients who were deceased, and possibly suffered a severe general deterioration and significant immunosuppression derived from the progression of the disease and the treatment administered. To the contrary, our group included recently diagnosed patients who still had good performance status.

Other factors to take into account when estimating the prevalence of colonization in different groups of patients have to do with methodological aspects. The type of sample analyzed, the DNA extraction method, the molecular targets used, and the PCR method also influence the sensitivity and specificity,44 and may explain some of the relevant variations in the prevalence estimates that have been published in very similar groups of patients.1,48 The molecular technique used in our study was qPCR targeting mtLSUrRNA (with a detection limit of >10 DNA copies per reaction). This methodology is widely accepted due to its high sensitivity and specificity.38 There are many studies in which nested PCR is used with the same target. This technique offers more sensitivity, but also entails greater risk of false positives. Concerning the sampling techniques, the invasive ones, that directly access the lower respiratory tract, such as BAL, are more reliable, as Pneumocystis is a colonizer of the alveolar space, associated with type I pneumocytes. This also explains the high colonization rates registered in studies on lung tissue harvested post-mortem.11,43

There was no statistically significant relationship of any of the variables considered in the study with P. jirovecii finding, but six of our seven positive patients were or had been smokers. Therefore, the lack of significance may be due to the fact that the proportion of positive patients is low. In this sense, other authors also describe this higher prevalence of colonization related to smoking habit in patients with ILD,46 cancer39 and in HIV-positive patients.24 Therefore, the connection between P. jirovecii colonization and smoking seems to be consistent.

As for the possible existence of an environmental niche that may act as a source of infection for colonized adults, in our study, P. jirovecii was not detected in any of the 49 domestic dust samples, even though five were from the homes of colonized patients. These results differ from those published in the study by Maher et al.,20 where dust samples were taken from different homes using two different devices (filter cassette and vacuum cleaner). In that study, Pneumocystis was detected in dust samples up to 96.6% using the cassette filter. These devices are capable of capturing large amounts of dust, greater than that obtained swabbing the surfaces in our study, so this may bias our results, and we recognize that it is a limitation of this study. Despite the results obtained in the study by Maher et al., the viability of Pneumocystis in the environment has not yet been demonstrated. Most of the studies published so far reinforce the idea that the ecological niche of Pneumocystis species is the lower respiratory tract of mammals, and that transmission is airborne from individual to individual. The parasitic nature of this fungus is another factor in favour of this interpretation. Its genome lacks many of the genes involved in de novo biosynthesis of essential nutrients, while it does code mechanisms to obtain nutrients from the host.8

Our results back the idea that the presence of P. jirovecii in the lower respiratory tract has a relevant relationship with the individual's immune status, not with an underlying pathology. As previously proposed, this fungus can be acquired at different times in life, by air, from individual carriers. Once acquired, it can temporarily form part of the lower respiratory tract microbiome, but healthy individuals eliminate it through the action of a competent immune system. Therefore, colonization rates in these cases are null or very low. The increase in the prevalence of carriers is directly related to the immunological situation of the individuals, which may be the consequence of a certain pathology and/or immunosuppressive therapy.

FundingThis work has been funded with two competitive grants from Fundación Española del Pulmón (SEPAR 2016/026) and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria y Biomédica de Alicante (ISABIAL2019/190296).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors acknowledge the laboratory technical assistance of Javier Puentes, and Miguel Valverde for the technical assistance in statistics. We also thank the generous contribution of the patients who gave their approval to use their clinical samples, and especially those who allowed us to sample from their homes.