Trichosporon genus encompasses emergent fungal pathogens with an increased incidence that concerns potential multi-drug resistance and mortality, especially in immunocompromised patients. COVID-19 is a disease of pandemic proportions with complications related to cytokine storm and lymphopenia.

AimsTo study the isolation of fungi within the Trichosporanaceae family in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.

MethodsIn this work we recovered 35 fungal isolates belonging to the Trichosporonaceae family from urine samples of 32 patients hospitalized due to COVID-19 complications. We evaluated their mycological characteristics, as well as the patient's clinical aspects.

ResultsTrichosporon asahii was the main species identified, followed by Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii and Trichosporon inkin, respectively. The blood cultures of 20 of these patients were all negative for fungi. Isolation of Trichosporonaceae fungi in urine was associated with high COVID-19 severity. The antifungal susceptibility test showed low MIC values for voriconazole, an antifungal in the first-line treatment of trichosporonosis. In contrast, high MIC values were found in the case of amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine in all the species, except for C. jirovecii. Since invasive trichosporonosis was not confirmed, none of the patients were given an antifungal treatment, without affecting the outcome of the patients.

ConclusionsOur results suggest that the isolation in urine of fungi from the Trichosporonaceae family may be associated to more severe forms of the disease COVID-19, but not with an increase in death rate. However, these isolates do not seem to be linked to urinary infections, therefore no antifungal therapy is mandatory in these cases.

Trichosporon engloba un grupo de hongos patógenos emergentes cuya incidencia creciente genera preocupación debido a su potencial resistencia a múltiples fármacos y a la mortalidad que provocan, especialmente en los pacientes inmunocomprometidos. A su vez, COVID-19 es una enfermedad con complicaciones relacionadas con la tormenta de las citoquinas y la linfopenia. Sin embargo, se sabe poco sobre el aislamiento de especies de Trichosporon en los pacientes infectados por el SARS-CoV-2.

ObjetivosEstudiar el aislamiento de especies de la familia Trichosporonaceae en la orina de los pacientes infectados con SARS-CoV-2.

MétodosEn esta investigación estudiamos 35 aislamientos de la familia Trichosporonaceae aislados de muestras de orina de 32 pacientes hospitalizados por complicaciones de COVID-19. Se evaluaron tanto las características de cada aislamiento como los aspectos clínicos de los pacientes.

ResultadosLas especies identificadas fundamentalmente fueron Trichosporon asahii, seguida de Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii y Trichosporon inkin. No se aislaron hongos de los cultivos sanguíneos de 20 de estos pacientes. El aislamiento en la orina de estos hongos de la familia Trichosporonaceae se correlacionó con una mayor gravedad por COVID-19. La prueba de sensibilidad antifúngica mostró valores de concentración mínima inhibitoria (CMI) bajos para el voriconazol, el fármaco principal para tratar la tricosporonosis. Contrariamente, los valores CMI para la anfotericina B y la 5-fluorocitosina fueron altos en todas las especies, excepto en C. jirovecii. Dado que no se diagnosticó una tricosporonosis invasiva en ninguno de los pacientes, no se instauró ningún tratamiento antifúngico, hecho que no influyó en la evolución de los pacientes.

ConclusionesNuestros resultados sugieren que el aislamiento de hongos de la familia Trichosporonaceae a partir de muestras de orina podría relacionarse con formas más graves de COVID-19, aunque no parece afectar la tasa de mortalidad. Sin embargo, estos aislamientos no parecen asociarse a una infección urinaria, por lo que la terapia antifúngica no es imperativa en estos casos.

Trichosporon spp. are basidiomycetous yeast-like fungi widely distributed in nature.19Trichosporon taxonomy has been reassessed, and there is a new classification based on molecular phylogenetic analysis. Thus, some pathogenic species previously classified within the Trichosporon genus belong now to other genera, such as Apiotrichum and Cutaneotrichosporon.31 Among these pathogenic Trichosporonaceae species, we can mention Apiotrichum montevideense (formerly Trichosporon montevideense) and Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii (formerly Trichosporon jirovecii), for example.

These genera have been recognized as emergent human pathogens causing life-threatening fungal invasive infections associated with high mortality rates and an increasing morbidity in the last decades.30 Gut translocation and intravascular or urinary catheters are considered the primary sources of Trichosporon infection. Despite antifungal therapy treatment, mortality among patients can range from 42 to 80%.2,19,28,43,47 Invasive trichosporonosis occurs in immunocompromised patients mainly, especially in those with hematological malignancies, high corticosteroid dose treatment, prolonged antibiotic treatment, and in those patients requiring longer hospital stays. Nevertheless, immunocompetent people may also be affected.19,28

Trichosporon incidence seems high in Brazil. Trichosporon asahii is the most common species identified (76.26%), followed by Trichosporon inkin (9.78%), being isolated mainly in urine (43.30%) and blood (22.90%) samples.24 In a Brazilian multicenter study, the incidence of T. asahii fungemia ranged from 0.5 to 2 positive cultures per 10,000 admissions each year.25 Although T. asahii remains the most frequently species related to Trichosporon fungemia in Brazil, the diversity of species within the Trichosporonaceae family isolated from clinical specimens has increased over the years.24

The lack of guidelines on treatment, as well as fast, accurate diagnostic tools, are critical points that deserve attention. An invasive trichosporonosis is considered proven when there is a positive culture from any sample taken in sterile sites in patients with clinical signs of infection, or there is a positive culture from a biopsy specimen together with histopathological evidence of the presence of Trichosporon.19,21 Therefore, isolating any fungus of the Trichosporonaceae family from non-sterile sites does not confirm an invasive trichosporonosis. The challenge of the diagnosis rely on the time demand and the difficulty of attaining a species-specific diagnostic. However, non-culture-based methods may help in the diagnose of invasive trichosporonosis and be useful to reach a diagnosis coupled with other clinical and epidemiological evidences.19

Since the first case reported in Wuhan, China, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) took pandemic proportions, with millions of deaths worldwide. Infections due to SARS-CoV-2 may be severe mainly due to the cytokine storm and lymphopenia, with a decrease in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and, consequently, in the IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells, which is narrowly related to the severity of the infection and a greater risk of developing secondary diseases.17 Mechanical ventilation and prolonged use of catheters and corticoids are risk factors usually present in moderate and severe COVID-19 patients, and those risks are shared with invasive mycoses,39 including invasive trichosporonosis. Nevertheless, little is known about the correlation between SARS-CoV-2 and Trichosporon coinfection, especially its incidence and clinical prognosis. There are few reports on trichosporonosis in COVID-19 patients. One study reported a brain abscess caused by Trichosporon dohaense in a diabetic patient one and a half month after COVID-19 development.44 Recent studies have also reported T. asahii fungemia in critically ill COVID-19 patients under cytokines storm and using immunosuppressant agents.1,32,36,45

Nosocomial urinary tract infections play an important role in patients’ prognosis, especially in intensive care units.11 The extensive and prolonged use of catheters, associated with other risk factors, allows colonization and biofilm formation by opportunistic microorganisms in the urinary tract. Infections are common in these patients.11,19 Though blood culture is the most recommended test to diagnose invasive diseases, the sampling of other specimens, such as urine, is an alternative to diagnose invasive infections and improve the patient's prognosis.

Since urine is the primary clinical specimen yielding positive Trichosporon cultures,24 the present study aims to describe the isolation of Trichosporon species from urine samples in patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in a Brazilian care center, as well as the antifungal susceptibility profiles of those strains and the association with patients’ clinical parameters.

Materials and methodsPatients and study designThis research was a prospective and observational nested case-control study conducted at the Evandro Chagas National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between October 2020 and September 2021. The study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the institution (CAAE: 31578820.9.0000.5262). An informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study. Two groups of patients were studied. The first group comprised adult patients diagnosed with COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2 presence was demonstrated by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR]), hospitalized due to COVID-19 complications, and with a urine culture positive for Trichosporon or other related genera (Apiotrichum or Cutaneotrichosporon). The control group encompassed hospitalized patients with COVID-19 diagnosed as described for the first group, but without microbial growth in cultures of urine samples during the hospital stay. These patients were randomly chosen to match similar hospital units and the time of admission of those patients in the Trichosporon group. In addition, demographic data (age, gender), and clinical information (underlying conditions, use of mechanical ventilation, use of vasoactive amine drugs, renal replacement therapy, laboratory tests, previous antimicrobial exposure, previous antifungal exposure, and days of hospitalization) were retrieved from the medical records of patients of both groups in order to perform comparative outcomes. For the purpose of predicting fungemia, we also evaluated previous bacterial or fungal infections, and the Pitt bacteremia score was calculated. Pitt score is a parameter initially described to evaluate the severity of an acute illness in patients with bacteremia. Meanwhile, it has also been used in the stratification of the severity of candidemia and Trichosporon fungemias.36,49 All these data were analyzed anonymously.

Urine cultures and fungal isolationUp to three urine samples were collected from each patient and processed according to the following description. The first one was collected at admission and the other two at days 14 and 21 of hospitalization; nevertheless, some patients were discharged and some others died before the scheduled sampling was performed. These samples were collected in sterile vials and cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco, Becton-Dickinson and Company, USA) by sowing 100μl of urine on the culture medium, and incubating at 25°C for five weeks or until fungal growth was obtained, following the Brazilian Health Surveillance Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) recommendations.5 All fungi obtained from the samples were identified through MALDI-TOF MS (MALDI Biotyper – Bruker) using the database 4.1.100. After getting the species identification, the fungal isolates were preserved in glycerol 15% and stored at −80°C for further analyses.

Molecular identificationFungal isolates with a green (score ≥2.0) or yellow (2.0 Trichosporon with MALDI-TOF rapid identification were submitted to molecular tests to confirm the species identification. Seven day-cultures of each strain on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 30°C were used for DNA extraction as previously described.4 The DNA was used to amplify ribosomal genes of the Trichosporonaceae family by means of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Reactions were performed in a 50μL final volume containing 100ng of the genomic DNA, 0.45mM of each primer (NL1 5′-GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG-3′ and NL4 5′-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG-3′ for the D1/D2 region, ITS4 5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′ and ITS5 5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′ for the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region), 1.0U of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Waltham, USA), 1X PCR buffer (Invitrogen, Waltham, USA), 1.5mM MgCl2, 50mM KCl, and 0.2mM DNTPs (Invitrogen, Waltham, USA). The PCR was performed with an initial denaturation step of 5min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of DNA denaturation for 1min at 95°C, annealing for 1min at 55°C, extension for 1min at 72°C, and a final extension for 5min at 72°C. Amplified fragments (size expected D1/D2 region: 602–617bp, and ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region 521–536bp) were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and submitted to sequencing at the Genomic Sequencing Platform PDTIS/Fiocruz, Phylogenetic Analysis.

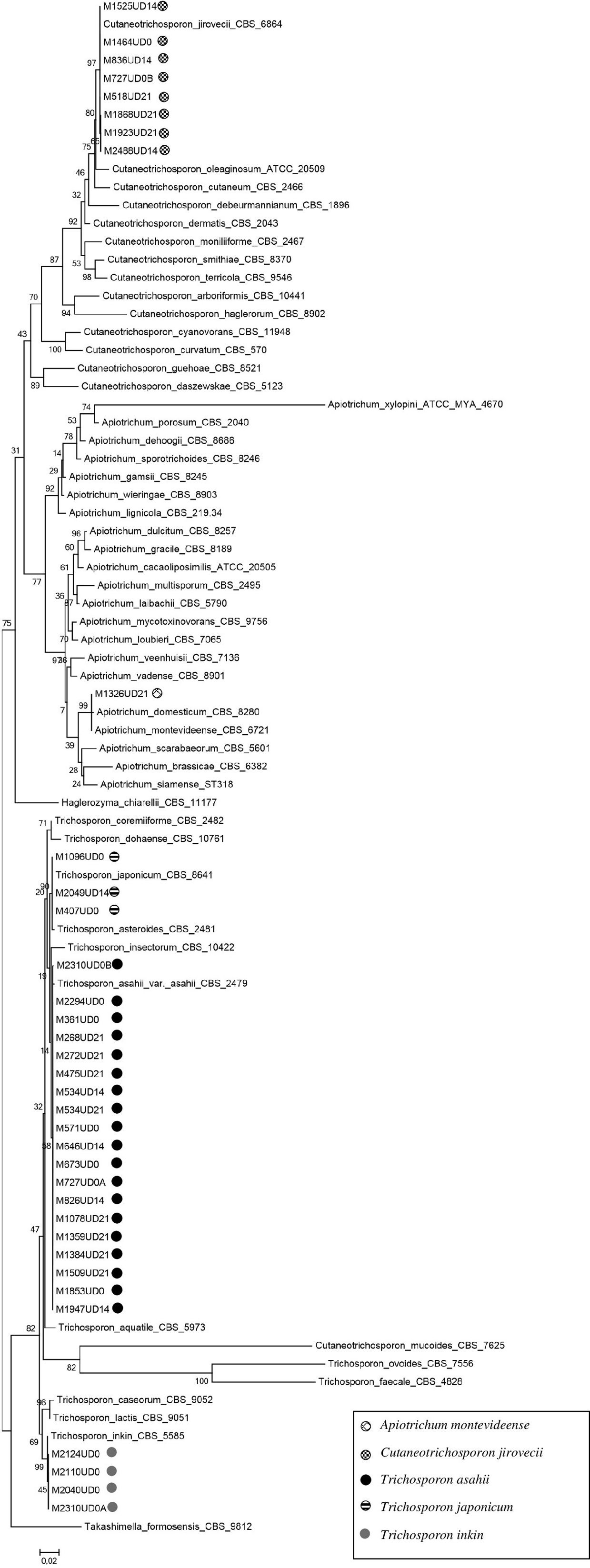

DNA sequences were edited using the Sequencher Software Package (version 4.9) and aligned using the software MEGA (version 11). Sequences of Trichosporonaceae species and the outgroup species Takashimella formosensis CBS 9812 deposited in the GenBank were used for the phylogenetic analysis. The phylogenetic tree was created using the maximum likelihood (ML) by bootstrap method (1000 replicates) and using Nearest Neighbor Interchange (NNI) within MEGA 11.27

Antifungal susceptibility testingThe Trichosporonaeceae isolates recovered underwent an antifungal susceptibility test using triazole derivatives (itraconazole, fluconazole, posaconazole and voriconazole), amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine, following the CLSI M27-A3 microdilution broth method.41 Drug dilutions ranged 0.13–64mg/L for fluconazole and 5-fluorocytosine, and 0.02–8mg/L for the other drugs. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest drug concentration able to inhibit 50% of fungal growth for 5-fluorocytocine and azole derivatives, and 90% of fungal growth for amphotericin B after 48h of incubation at 30°C.51Candida krusei ATCC 6258 and Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 were used as quality control strains in all test plates, and MIC values were determined after 24h. The experiment was repeated twice in different days for each strain to assure the precision (repeatability) and accuracy. MIC ranges, geometrical means, MIC50, and MIC90 values were calculated for all species/drug combinations, as described.23

Statistical analysesComparisons between groups were performed using Fisher's exact or Chi-square tests, when appropriate, for the qualitative variables, and the Mann–Whitney test in continuous variables using the median and interquartile range (IQR) to compare numerical values with normal distributions not assumed. Moreover, T-test with standard deviation was used for quantitative variables with normal distributions. p-Values were considered statistically significant when lower than 0.05. The R software version 4.2.1 and the package epiDisplay were used to perform the data analyses.

ResultsTrichosporon spp. and species related isolated from urine samplesBetween October 2020 and September 2021, 1134 urine samples from 835 patients with COVID-19, including those who were not followed-up due to death or hospital discharge before the study was completed, were submitted for mycological evaluation. Among them, 389 (34.30%) samples presented fungal growth, and 35 Trichosporonaceae species were identified from the urine of 32 COVID-19 patients. The frequency of Trichosporonaceae species isolated from urine was 3.83%. Colony form unit (CFU) counts varied from 10 to >103CFU/mL.

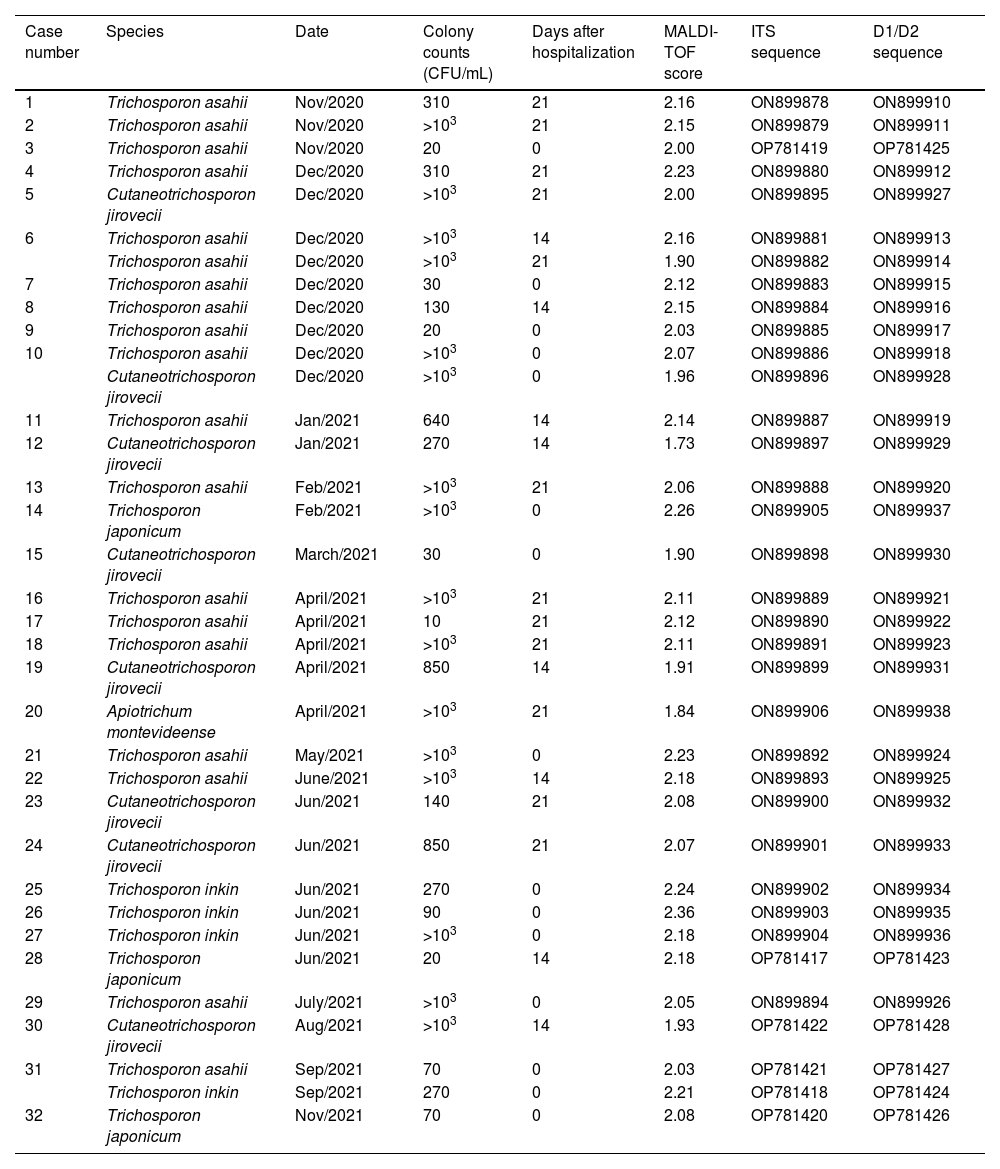

Table 1 presents the identification results of the strains included in this study. Molecular identification showed 100% concordance with MALDI-TOF results, as revealed by the phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1). T. asahii was the predominating species (19/35, 54.29%), followed by C. jirovecii (8/35, 22.86%), T. inkin (4/35, 11.43%), Trichosporon japonicum (3/35, 8.57%) and A. montevideense with one positive culture (1/35, 2.86%). Two urine cultures of two samples from one patient (after 14 and 21 days of hospitalization) yielded T. asahii. Two patients had two different Trichosporon species isolated from a single urine sample collected at admission (Table 1).

Data of urine culture, MALDI-TOF, and molecular identification of Trichosporonaceae strains isolated from COVID-19 patients.

| Case number | Species | Date | Colony counts (CFU/mL) | Days after hospitalization | MALDI-TOF score | ITS sequence | D1/D2 sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Trichosporon asahii | Nov/2020 | 310 | 21 | 2.16 | ON899878 | ON899910 |

| 2 | Trichosporon asahii | Nov/2020 | >103 | 21 | 2.15 | ON899879 | ON899911 |

| 3 | Trichosporon asahii | Nov/2020 | 20 | 0 | 2.00 | OP781419 | OP781425 |

| 4 | Trichosporon asahii | Dec/2020 | 310 | 21 | 2.23 | ON899880 | ON899912 |

| 5 | Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii | Dec/2020 | >103 | 21 | 2.00 | ON899895 | ON899927 |

| 6 | Trichosporon asahii | Dec/2020 | >103 | 14 | 2.16 | ON899881 | ON899913 |

| Trichosporon asahii | Dec/2020 | >103 | 21 | 1.90 | ON899882 | ON899914 | |

| 7 | Trichosporon asahii | Dec/2020 | 30 | 0 | 2.12 | ON899883 | ON899915 |

| 8 | Trichosporon asahii | Dec/2020 | 130 | 14 | 2.15 | ON899884 | ON899916 |

| 9 | Trichosporon asahii | Dec/2020 | 20 | 0 | 2.03 | ON899885 | ON899917 |

| 10 | Trichosporon asahii | Dec/2020 | >103 | 0 | 2.07 | ON899886 | ON899918 |

| Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii | Dec/2020 | >103 | 0 | 1.96 | ON899896 | ON899928 | |

| 11 | Trichosporon asahii | Jan/2021 | 640 | 14 | 2.14 | ON899887 | ON899919 |

| 12 | Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii | Jan/2021 | 270 | 14 | 1.73 | ON899897 | ON899929 |

| 13 | Trichosporon asahii | Feb/2021 | >103 | 21 | 2.06 | ON899888 | ON899920 |

| 14 | Trichosporon japonicum | Feb/2021 | >103 | 0 | 2.26 | ON899905 | ON899937 |

| 15 | Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii | March/2021 | 30 | 0 | 1.90 | ON899898 | ON899930 |

| 16 | Trichosporon asahii | April/2021 | >103 | 21 | 2.11 | ON899889 | ON899921 |

| 17 | Trichosporon asahii | April/2021 | 10 | 21 | 2.12 | ON899890 | ON899922 |

| 18 | Trichosporon asahii | April/2021 | >103 | 21 | 2.11 | ON899891 | ON899923 |

| 19 | Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii | April/2021 | 850 | 14 | 1.91 | ON899899 | ON899931 |

| 20 | Apiotrichum montevideense | April/2021 | >103 | 21 | 1.84 | ON899906 | ON899938 |

| 21 | Trichosporon asahii | May/2021 | >103 | 0 | 2.23 | ON899892 | ON899924 |

| 22 | Trichosporon asahii | June/2021 | >103 | 14 | 2.18 | ON899893 | ON899925 |

| 23 | Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii | Jun/2021 | 140 | 21 | 2.08 | ON899900 | ON899932 |

| 24 | Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii | Jun/2021 | 850 | 21 | 2.07 | ON899901 | ON899933 |

| 25 | Trichosporon inkin | Jun/2021 | 270 | 0 | 2.24 | ON899902 | ON899934 |

| 26 | Trichosporon inkin | Jun/2021 | 90 | 0 | 2.36 | ON899903 | ON899935 |

| 27 | Trichosporon inkin | Jun/2021 | >103 | 0 | 2.18 | ON899904 | ON899936 |

| 28 | Trichosporon japonicum | Jun/2021 | 20 | 14 | 2.18 | OP781417 | OP781423 |

| 29 | Trichosporon asahii | July/2021 | >103 | 0 | 2.05 | ON899894 | ON899926 |

| 30 | Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii | Aug/2021 | >103 | 14 | 1.93 | OP781422 | OP781428 |

| 31 | Trichosporon asahii | Sep/2021 | 70 | 0 | 2.03 | OP781421 | OP781427 |

| Trichosporon inkin | Sep/2021 | 270 | 0 | 2.21 | OP781418 | OP781424 | |

| 32 | Trichosporon japonicum | Nov/2021 | 70 | 0 | 2.08 | OP781420 | OP781426 |

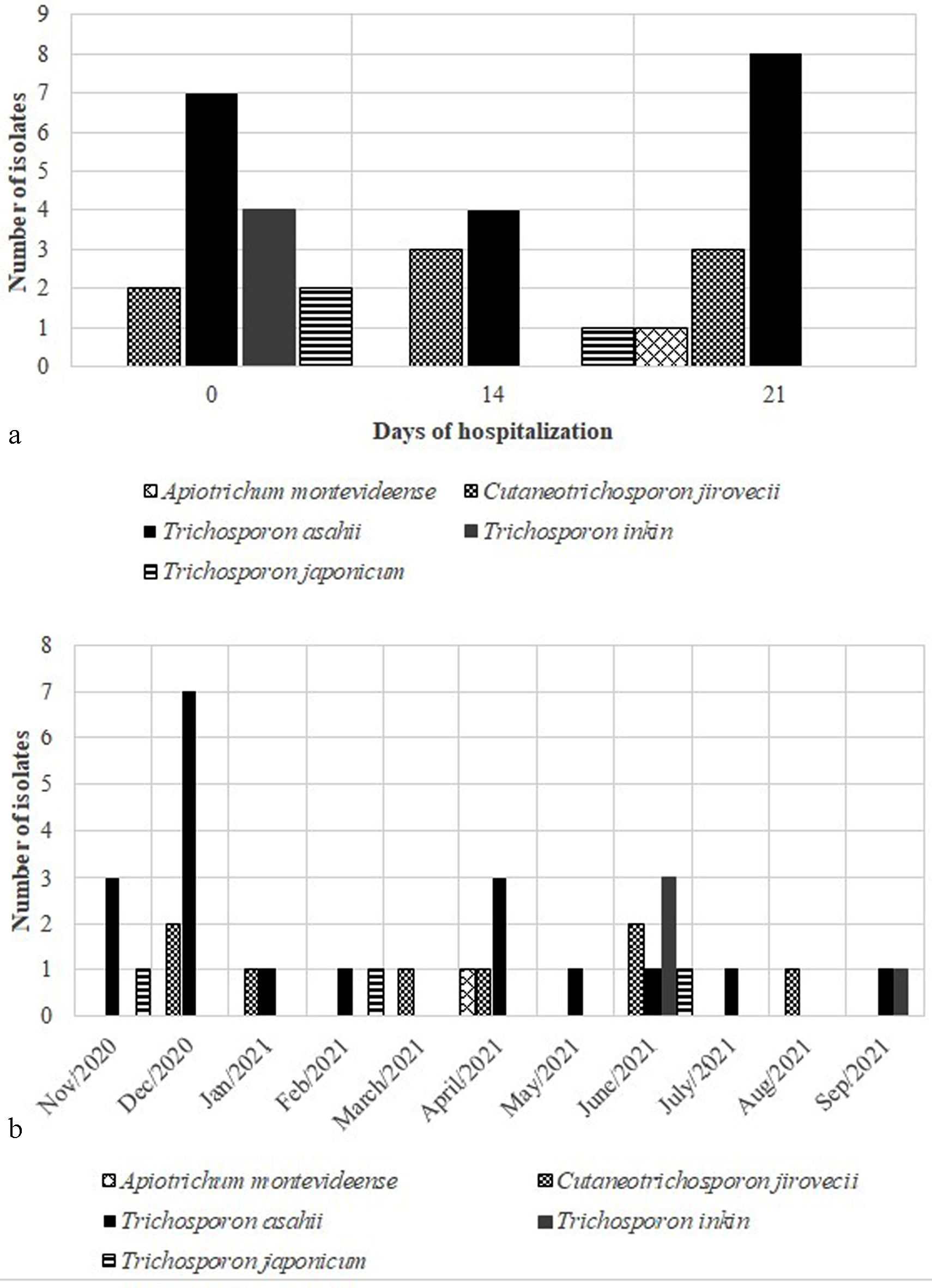

Trichosporonaceae species were isolated several times along patients’ length-of-stay, with higher frequency at admission (42.86%) and after 21 days of hospitalization (34.28%). In addition, the species T. asahii and C. jirovecii were widely identified in all the study period, as well as during all the length-of-stay (Fig. 2). The sudden increase of T. asahii isolations in December 2020 occurred together with the second wave of COVID-19 in Brazil, associated with the SARS-CoV-2 P.1 variant.

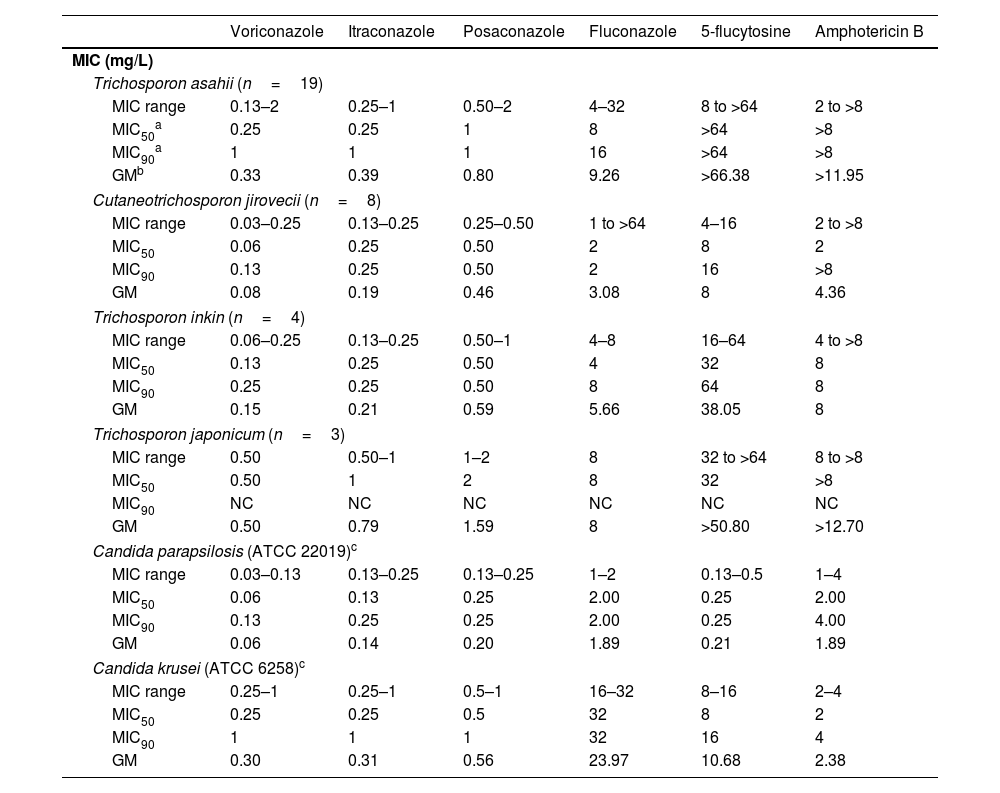

Susceptibility to antifungal drugsTable 2 summarizes the antifungal susceptibility of T. asahii, C. jirovecii, T. inkin, and T. japonicum to six antifungal drugs. In general, high amphotericin B MIC values were observed, with most of the isolates showing a lack of susceptibility to this drug, which is reflected in the MIC90 value, equal to or higher than 8mg/L. The amphotericin B MIC value for the species A. montevideense was also high (4mg/L). Moreover, 5-fluorocytosine MIC50 values were high (≥32mg/L), except for the species C. jirovecii, which showed a better response to this drug (MIC50 8mg/L).

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) (ml/L) of six antifungal drugs against Trichosporon spp.

| Voriconazole | Itraconazole | Posaconazole | Fluconazole | 5-flucytosine | Amphotericin B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) | ||||||

| Trichosporon asahii (n=19) | ||||||

| MIC range | 0.13–2 | 0.25–1 | 0.50–2 | 4–32 | 8 to >64 | 2 to >8 |

| MIC50a | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 8 | >64 | >8 |

| MIC90a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 16 | >64 | >8 |

| GMb | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.80 | 9.26 | >66.38 | >11.95 |

| Cutaneotrichosporon jirovecii (n=8) | ||||||

| MIC range | 0.03–0.25 | 0.13–0.25 | 0.25–0.50 | 1 to >64 | 4–16 | 2 to >8 |

| MIC50 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| MIC90 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 2 | 16 | >8 |

| GM | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.46 | 3.08 | 8 | 4.36 |

| Trichosporon inkin (n=4) | ||||||

| MIC range | 0.06–0.25 | 0.13–0.25 | 0.50–1 | 4–8 | 16–64 | 4 to >8 |

| MIC50 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 4 | 32 | 8 |

| MIC90 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 8 | 64 | 8 |

| GM | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.59 | 5.66 | 38.05 | 8 |

| Trichosporon japonicum (n=3) | ||||||

| MIC range | 0.50 | 0.50–1 | 1–2 | 8 | 32 to >64 | 8 to >8 |

| MIC50 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 32 | >8 |

| MIC90 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC |

| GM | 0.50 | 0.79 | 1.59 | 8 | >50.80 | >12.70 |

| Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019)c | ||||||

| MIC range | 0.03–0.13 | 0.13–0.25 | 0.13–0.25 | 1–2 | 0.13–0.5 | 1–4 |

| MIC50 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 2.00 | 0.25 | 2.00 |

| MIC90 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2.00 | 0.25 | 4.00 |

| GM | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 1.89 | 0.21 | 1.89 |

| Candida krusei (ATCC 6258)c | ||||||

| MIC range | 0.25–1 | 0.25–1 | 0.5–1 | 16–32 | 8–16 | 2–4 |

| MIC50 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 32 | 8 | 2 |

| MIC90 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 32 | 16 | 4 |

| GM | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 23.97 | 10.68 | 2.38 |

The MIC values obtained with most of the azoles were lower. Among them, voriconazole showed the lowest MIC50 values, followed by itraconazole, posaconazole, and fluconazole (Table 2). Fluconazole had broad MIC variations and high MIC50 values, especially for C. jirovecii (range 1 to >64mg/L), T. asahii (range 4–32mg/L), and A. montevideense (32mg/L). The single isolate of A. montevideense had the following MIC values (mg/L) for voriconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, 5-flucytosine, and amphotericin B: 1, 0.25, 0.50, >64, and 4, respectively.

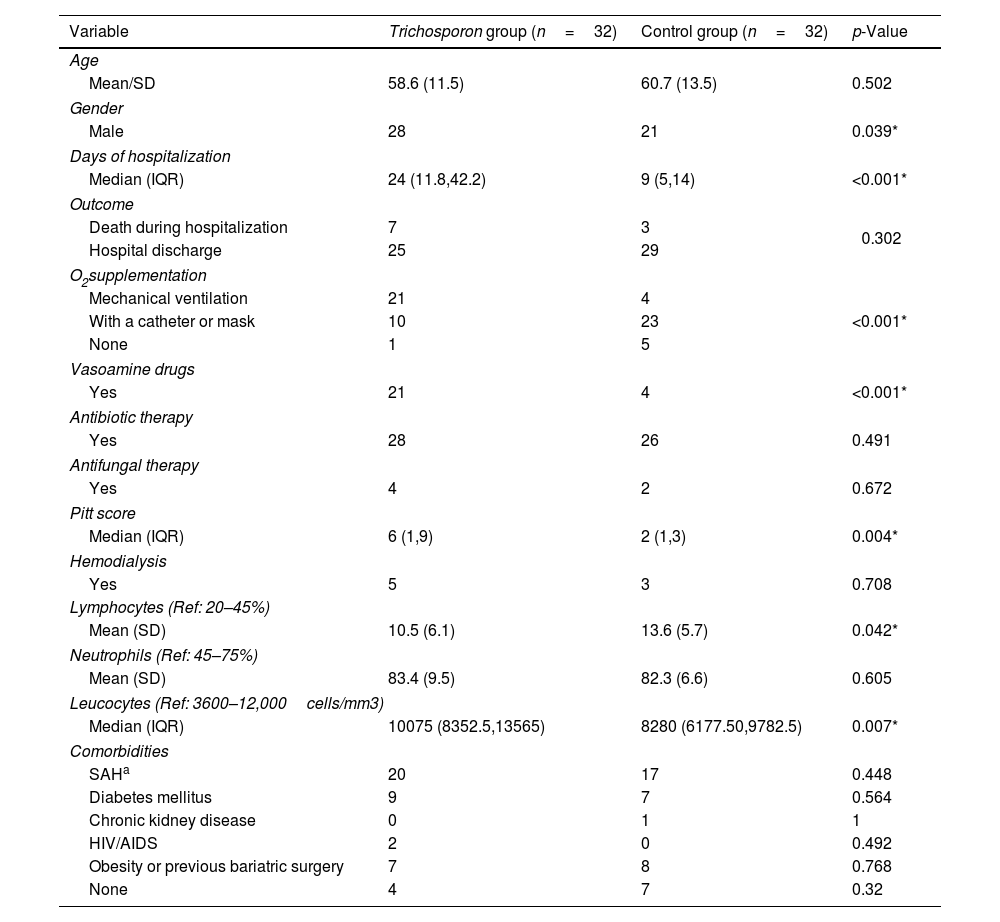

Clinical features of the patientsNo remarkable clinical features were observed in the urinary tract of the patients from whom Trichosporonaceae species were recovered from urine samples. Most of the patients were male (p=0.039), developed severe forms of COVID-19 that needed invasive procedures such as oxygen supplementation (p<0.001), used vasoactive amine drugs (p<0.001), and were hospitalized for a long time (median 35 and 12 days for the Trichosporonaceae and control groups, respectively, p<0.001), as depicted in Table 3. A higher leucocyte count was also observed in patients with Trichosporonaceae isolates (p=0.007), but lymphocyte counts were lower (p=0.042). Blood samples were obtained from 20 patients with suspected septicemia, but the culture of all the samples were negative for fungi. However, we obtained positive blood cultures for bacteria from eight patients, all of them in the Trichosporon group. This finding is in line with the significant p-value of the Pitt bacteremia score, p=0.004 (Table 3). There was no statistically supported relationship between comorbidities and the isolation of Trichosporonaceae species.

Clinical features of COVID-19 patients with and without a Trichosporonaceae strain isolated from urine during hospitalization.

| Variable | Trichosporon group (n=32) | Control group (n=32) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean/SD | 58.6 (11.5) | 60.7 (13.5) | 0.502 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 28 | 21 | 0.039* |

| Days of hospitalization | |||

| Median (IQR) | 24 (11.8,42.2) | 9 (5,14) | <0.001* |

| Outcome | |||

| Death during hospitalization | 7 | 3 | 0.302 |

| Hospital discharge | 25 | 29 | |

| O2supplementation | |||

| Mechanical ventilation | 21 | 4 | |

| With a catheter or mask | 10 | 23 | <0.001* |

| None | 1 | 5 | |

| Vasoamine drugs | |||

| Yes | 21 | 4 | <0.001* |

| Antibiotic therapy | |||

| Yes | 28 | 26 | 0.491 |

| Antifungal therapy | |||

| Yes | 4 | 2 | 0.672 |

| Pitt score | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (1,9) | 2 (1,3) | 0.004* |

| Hemodialysis | |||

| Yes | 5 | 3 | 0.708 |

| Lymphocytes (Ref: 20–45%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 10.5 (6.1) | 13.6 (5.7) | 0.042* |

| Neutrophils (Ref: 45–75%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 83.4 (9.5) | 82.3 (6.6) | 0.605 |

| Leucocytes (Ref: 3600–12,000cells/mm3) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 10075 (8352.5,13565) | 8280 (6177.50,9782.5) | 0.007* |

| Comorbidities | |||

| SAHa | 20 | 17 | 0.448 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 | 7 | 0.564 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| HIV/AIDS | 2 | 0 | 0.492 |

| Obesity or previous bariatric surgery | 7 | 8 | 0.768 |

| None | 4 | 7 | 0.32 |

At hospital admission, two patients in the control group admitted in April and May 2021 had been vaccinated against COVID-19, while all patients with Trichosporonaceae isolates had not been vaccinated. The crude death rate among COVID-19 patients in the control group was 0.9 per 1000 patients, against 2.2 per 1000 patients in the Trichosporon group. Although higher, the difference in the death rate was not significant (p=0.3). Patients with T. asahii isolation in urine (3.9 per 1000 patients) had a high mortality rate, while all patients with non-T. asahii species were discharged. Regarding the patient who had concomitant isolation of T. asahii and C. jirovecii, a bad outcome occurred after prolonged hospitalization and the use of vasoamine drugs, antibiotics, and micafungin therapy. A patient with severe COVID-19 and T. asahii isolation in urine treated with amphotericin B also died 13 days after admission.

DiscussionThe concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic expand beyond its severity due to the life-threatening opportunistic diseases that can worsen the patient's prognosis. Several research groups report an imminent risk to the development of fungal coinfections in severely ill COVID-19 patients, especially aspergillosis,8,12,29,33 invasive candidiasis,3,7,39,40 and mucormycosis.22,38,46 Cases of T. asahii infection associated with COVID-19 have also been reported,1,13,15,20,32,36,45,50 as well as a T. dohaense brain abscess case.44 The present study shows a 3.8% frequency of positive urine cultures for Trichosporonaceae species in patients with COVID-19, where T. asahii was the main species. Previous studies reported an incidence of 0.5–2 cases of T. asahii per 10,000 hospital admissions in Brazilian centers.25 On the other hand, the study of a cohort of COVID-19 patients with T. asahii fungemia in an intensive care unit suggested that this incidence may be higher.36

In our work, we found other Trichosporonaceae species besides T. asahii in COVID-19 patients, which was associated with poor prognosis. Despite T. asahii predominance, increased Trichosporon species diversity has been found in human samples over the years. In this work, we also found non-T. asahii species, which are not usually reported in urine samples, such as A. montevideense. In addition, we observed a representative number of C. jirovecii strains. This species is underreported in humans, especially in urine samples.42 This may indicate the emergence of novel fungal pathogens rarely associated with humans and potentially dangerous to vulnerable patients, such as those in this study.

Our results show that both molecular and MALDI-TOF techniques discriminate the Trichosporonaceae species appropriately, at least those encountered in this study, as reported previously.37 The MALDI-TOF has the advantage of providing a quick identification, after an easy and fast protein extraction process, when there is fungal growth in the culture media. Together with other diagnostic tools, it can be beneficial in routine diagnostics.

Currently, there are no randomized clinical trials to determine the best antifungal treatment for invasive trichosporonosis. However, the MIC values exhibited by the Trichosporon species can be useful to implement guidelines that may help in choosing the appropriate antifungal therapy after the species identification.35 In this work, the strains recovered showed high MIC values for amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine. C. jirovecii showed a lower mean MIC value for 5-fluorocytosine, though. According to the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and the European Confederation of Medical Mycology guidelines, many Trichosporon species are resistant to amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine, with high MIC values in vitro,9,16 supporting the findings of this work. Therefore, the triazoles appear to be a good therapeutic choice, with good in vitro and in vivo results against invasive trichosporonosis.18 Furthermore, our in vitro antifungal susceptibility test results showed that the strains studied herein were susceptible to azole derivatives, especially to voriconazole, itraconazole, and posaconazole. This is also reported by previous studies that recommend triazoles as the best treatment option, with voriconazole as the first-line antifungal to treat invasive trichosporonosis.6,10,14,26,42,48

COVID-19 causes transitory immunosuppression through the reduction of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells,17 associated with underline conditions such as diabetes, cancer, AIDS, and prolonged use of antibiotic therapy, which can increase the likelihood of opportunistic fungal infections. Recent studies show an association of Trichosporon fungemia in diabetic patients with COVID-19.1,36,44 However, our work has not found a positive correlation between underlying diseases and Trichosporon or other sibling genera isolated in urine. This may be associated with the lack of positive blood cultures, that is, with invasive trichosporonosis, in the patients whose blood samples were subjected to that test.

Even though no fungal growth was obtained in any blood culture, in eight patients with Trichosporonaceae species isolated in urine samples bacterial growth was observed in their blood samples. According to the significant Pitt bacteremia score (p-value <0.004) in this group (Table 3), it may not necessarily rule out a possible invasive trichosporonosis. There were limitations in collecting, culturing, and accurately detecting microorganisms, especially fungal species, from blood cultures during the emergency pandemic situation.

Once the performance of a proper culture or getting the identification of any microorganism recovered from blood may suffer restrictions, the urine culture may be a test to early detect Trichosporon and lead to prescribe antifungal medication the sooner. Urine samples can be very useful as urine may be the first sample to render Trichosporon in culture in the setting of a disseminated disease.34 Furthermore, this sample is considered easy to collect and analyze if compared with blood samples. High fungal CFU counts in urine samples should not be underestimated, especially in high-risk cases. The early suspicion and detection may play a crucial role in the medical approach, likely reducing the risk of disseminated disease and mortality.20

It is well known that catheters, mechanical ventilation, prolonged corticoid use, and empirical antibiotic and antifungal therapy increase the risk of coinfections in COVID-19 patients. Most of our patients with Trichosporonaceae species isolated in urine met at least one of the aforementioned characteristics. Furthermore, these patients had longer hospital length-of-stay and higher leucocyte counts, probably associated with COVID-19 severity or even coinfections. However, in our study it was not possible to perform a logistic multivariate analysis due to the low number of patients and high quantity of variables. To confirm our observations, future studies with a large number of patients are necessary. We suggest that the isolation in urine of species within the Trichosporonaceae family is a sign of bad prognosis in COVID-19, not necessarily related to fungemia. Its detection highlights the importance of suspecting Trichosporon as an infection cause, especially in patients with severe COVID-19.

ConclusionsThe Trichosporonaceae members are emergent opportunistic fungal pathogens that may cause invasive infections leading to death in some cases. In patients with COVID-19, the isolation of these pathogens in urine can help in determining the patient's prognosis. Appropriate identification is important for epidemiologic purposes, and a proper treatment must be considered depending on the general condition of the patient and if these fungi are isolated in blood cultures.

CRediT authorship contribution statementConceptualization, R.M.Z.-O.; methodology, A.R.B.-E., F.A.-S., M.M.T., R.A.-P.; formal analysis, F.A.O., M.M.T., A.D.F., R.A.-P.; investigation, F.A.O., B.S.M., M.A.A., A.D.F., K.M.G., M.P.D.R.; resources, V.G.V., B.G., R.M.Z.-O.; data curation, F.A.O., K.M.G., M.P.D.R.; writing – original draft preparation, F.A.O., R.A.-P.; writing – review and editing, A.R.B.-E., F.A.-S., B.S.M., M.A.A., A.D.F., V.G.V., B.G., R.M.Z.-O.; visualization, F.A.O., M.M.T., R.A.P.; supervision, R.M.Z.O.; project administration, B.G., R.M.Z.O.; funding acquisition, R.M.Z.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Evandro Chagas National Institute of Infectious Diseases, approval number: 31578820.9.0000.5262, approval date: 16 May 2020.

FundingThis research was partially funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (405653/2021-2 and 403296/2021-8) and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil) – Finance Code 001. R.M.Z-O is supported in part by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico [CNPq 308315/2021-9] and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro [FAPERJ E-26/200.381/2023]. F.A.O. received a scholarship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES 88887.815716/2023-00). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare having no conflict of interest.

We are thankful to all professionals involved in the RECOVER project for their helpful support with the clinical database, and to Raquel de Vasconcelos Carvalhaes Oliveira for helping us with the statistical analysis. We also thank the workers of the Centro Hospitalar COVID-19 in the Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz for the administrative and technical support.