Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can arise from insertions in exon 20 of the EGFR gene, among other alterations. We carried out an external quality assessment (EQA) to evaluate the accuracy of laboratory methods and to highlight the importance of detecting and identifying genetic alterations, such as EGFR exon 20 insertion, in patients with NSCLC.

Materials and methodsThe 2021 EGRF exon 20 EQA program consisted of two rounds, in which four formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens (round 1: two positive for EGFR exon 20 insertions/duplications, one positive for a common EGFR alteration, and one wild-type; round 2: three positive for EGFR exon 20 insertions/duplications and one wild-type) obtained from patients with NSCLC were tested.

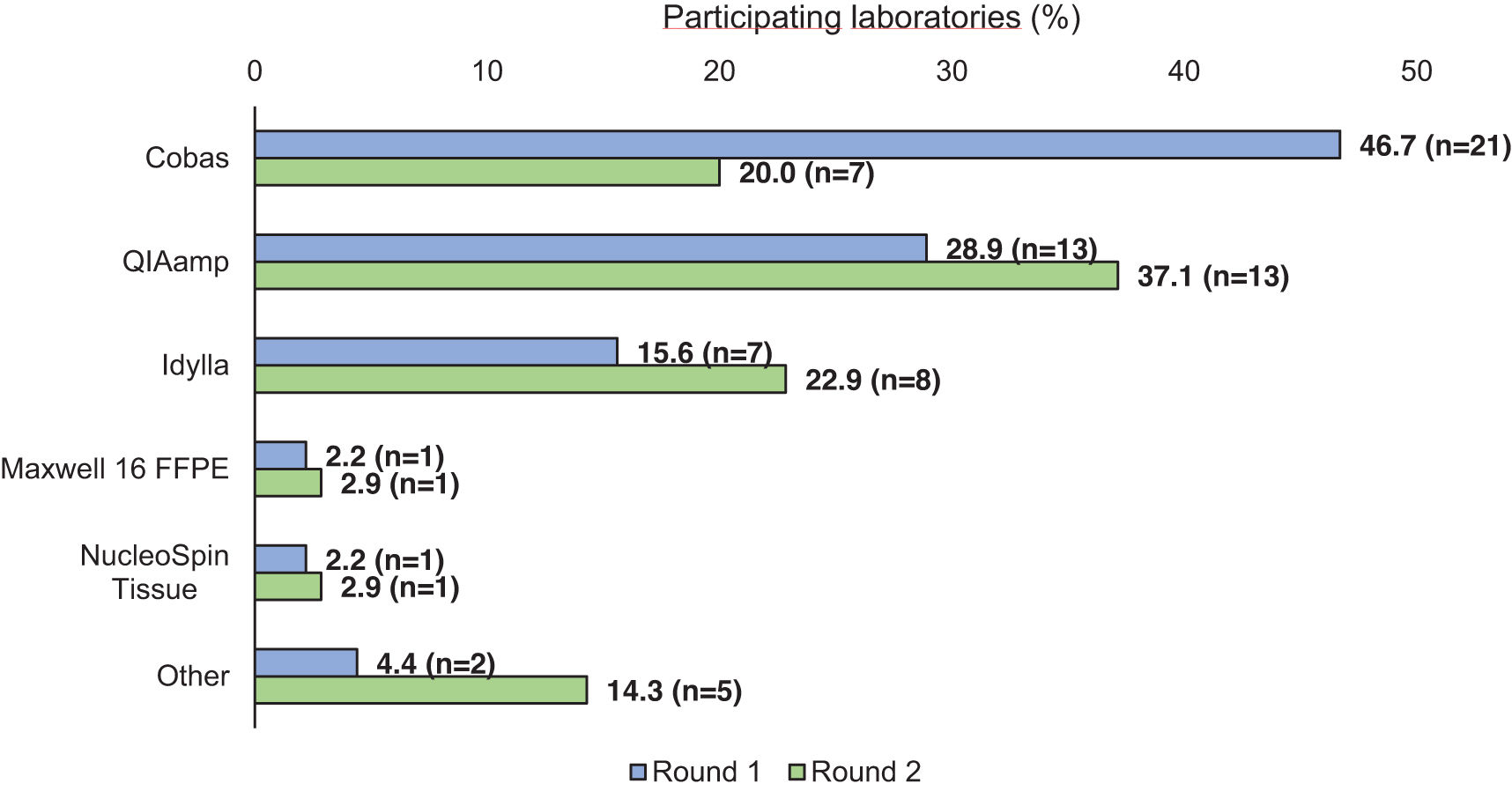

ResultsApproximately 80% of the invited laboratories participated in each round. The most common DNA isolation techniques used were the cobas® DNA Sample Preparation Kit (46.7%) in round 1 and QIAamp (37.1%) in round 2. The most frequently used genotyping method in both rounds was the cobas® EGFR Mutation Test (round 1: 53.3%; round 2: 37.1%). In both rounds, 71.1% and 73.6% of the tests, respectively, reported the expected result. The lowest success rate was observed in the H773delinsRY Exon 20 determination (round 1: 17.8%; round 2: 31.4%). This alteration was correctly determined only by next-generation sequencing.

ConclusionsThe variability in the genotyping methods and the success rate obtained in our study highlight the importance of EQA in Spain to ensure high performance.

El cáncer de pulmón no microcítico (CPNM) puede surgir de inserciones en el exón 20 del gen EGFR, entre otras alteraciones moleculares. El objetivo fue realizar un control de calidad externo (CCE) para evaluar la precisión de los métodos de laboratorio y resaltar la importancia de detectar e identificar alteraciones genéticas, como las inserciones en el exón 20 de EGFR, en pacientes con CPNM.

Materiales y métodosEl CCE de 2021 consistió en dos rondas con cuatro muestras fijadas en formalina e incluidas en parafina de pacientes con CPNM (ronda 1: dos con inserciones/duplicaciones del exón 20 de EGFR, una con una alteración común de EGFR y una wild-type; ronda 2: tres con inserciones/duplicaciones del exón 20 de EGFR y una wild-type).

ResultadosAproximadamente el 80% de los laboratorios invitados participaron en cada ronda. Las técnicas de extracción de ADN más utilizadas fueron el kit cobas® (46,7%) en la ronda 1 y QIAamp (37,1%) en la ronda 2. El método de determinación del genotipo más utilizado fue la prueba cobas® EGFR (ronda 1: 53,3%; ronda 2: 37,1%). El 71,1% y 73,6% de las pruebas dieron el resultado esperado en las rondas 1 y 2, respectivamente. La menor tasa de éxito se encontró en la alteración del exón 20 H773delinsRY (ronda 1: 17,8%; ronda 2: 31,4%), correctamente identificada solo mediante secuenciación masiva.

ConclusionesLa variabilidad en los métodos de determinación del genotipo y la tasa de éxito obtenida destacan la necesidad de programas de CCE en España que garanticen la aplicación de técnicas más adecuadas.

Lung cancer is one of the most common types of cancer, accounting for approximately 12% of all cancer diagnoses, and is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Spain, Europe, and the United States.1–3 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer, representing 85% of cases.4

Lung cancer can arise from molecular alterations in multiple driver genes.5 Interventions of these alterations with targeted therapies have improved outcomes.6,7 One of the most frequently affected genes is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR); several different mutations have been described, primarily deletions in exon 19, point mutations in exons 18 and 21,7 and over 100 insertions in exon 20.8 Despite EGFR exon 20 insertions occurring at a low frequency (1–2% of all NSCLC cases),9 their identification has been crucial, as patients with this alteration can show resistance to therapy with first- and second-generation of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors.8,9

Historically, direct DNA sequencing extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue has been considered the gold standard for detecting EGFR mutations.10,11 However, various molecular approaches have been developed over the past decades. Among these, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods, especially real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), or next-generation sequencing (NGS),can be highlighted.11 qPCR is easy to use and more tolerant of variable DNA quality. However, it allows the detection of only a limited number of specific, known alterations due to its low capability for multiplexing and the variable limit of detection for low-frequency alterations, depending on the commercial or in-house kits used.8,12 In contrast, NGS allows the simultaneous detection of multiple known and unknown mutations and offers higher sensitivity and specificity.8 NGS has become more widespread over the past decade, to the detriment of qPCR.13 Due to the use of this technology in recent years, more variants in exons 18, 19, 20, and 21 have been described,7 introducing greater complexity into the molecular diagnosis of EGFR mutations and the treatment of patients harboring these variants. Among these, new insights have been gained into EGFR exon 20 insertions, leading to the development of new treatments.14,15

In laboratory medicine, external quality assessments (EQA) are designed to evaluate the accuracy of laboratory tests and improving the quality of testing.16,17 In addition, an EQA allows comparison of results from one laboratory with those obtained elsewhere.18 In the context of evidence-based and personalized medicine, where diagnostic results must be accurate and reliable, EQA provides a valuable and objective evaluation to determine the extent to which a diagnostic method is susceptible to errors.16 In Spain, the Spanish Society of Anatomical Pathology (Sociedad Española de Anatomía Patológica, SEAP) organizes EQA programs to evaluate the quality of biomarker testing for NSCLC in Spanish laboratories.

Considering the above, the main goal of the study was to highlight the importance of detecting and identifying genetic alterations, such as the insertion in EGFR exon 20, in patients with NSCLC, due to the potential use of targeted therapies. Additionally, the study aimed to raise awareness about the use of appropriate techniques to detect this particular alteration.

Material and methodsStudy designThe EGFR exon 20 EQA program, organized by SEAP in 2021, consisted of two series of four FFPE specimens obtained from NSCLC patients who underwent tissue biopsy or surgical resection at two Spanish hospitals (Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, and Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Seville). These specimens had been previously tested as part of routine procedures to detect EGFR gene mutations. The specimens in round 1 included two positive for EGFR exon 20 insertions/duplications; one positive for a common EGFR alteration (exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R) and one wild-type (WT) sample. Round 2 included the following three specimens positive for EGFR exon 20 insertions/duplications and one WT sample.

Preparation of the reference samplesSerial tissue sections from FFPE specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to assess the proportion of tumor cells. Macro-dissection was conducted to enrich neoplastic fraction of the sample.

DNA was isolated from FFPE specimens using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit™ (Qiagen) and quantified by fluorometric detection using Qubit 3.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific™).

All samples were tested twice (samples obtained from one center were re-tested at the other one) using two different qPCR kits (cobas® EGFR Mutation Test v2 [Roche] and Idylla™ EGFR Mutation Assay) and a targeted amplicon-based NGS panel (Oncomine Focus Assay kit [Thermo Fisher Scientific™]). The qPCR with the cobas® EGFR Mutation Test v2 (Roche) was conducted using the cobas Z480 analyser, while the Idylla™ EGFR Mutation Assay was performed on the Idylla™ Platform (Idylla™ System and Console). For library preparation, DNA was amplified through multiplex PCR using the Ion Chef System (Thermo Fisher Scientific™), followed by template preparation on the same system. The libraries were then loaded onto an Ion chip and sequenced using the Ion S5 sequencing system. Results from both laboratories were compared to analyze possible discrepancies. The EGFR exon 20 insertions/duplications detected by the cobas® EGFR Mutation Test v2 (Roche) and the Idylla™ EGFR Mutation Assay differed in type and number: three were detected by the first method and five by the second.

ResultsParticipationIn the first round of the study, samples were sent to 56 laboratories across 14 different Spanish Autonomous Regions. Of these, 45 (80.4%) laboratories participated in the study. In the second round, 44 (78.6%) of the initial 56 laboratories accepted the invitation to participate. Of these, 35 (79.6%) laboratories from 14 Autonomous Regions finally participated in the second round.

DNA isolationMost of the participating laboratories in the first round (n=21, 46.7%) used the cobas® DNA Sample Preparation Kit, followed by QIAamp, used by 13 (28.9%) laboratories (Fig. 1). In the second round, the most frequently used method for DNA isolation was cobas® (n=13, 31.1%), followed by the Idylla™ Mutation Assay (n=8, 22.9%) and QIAamp (n=7, 20.0%) (Fig. 1).

GenotypingGenotyping methodsThe approach most frequently used in the first round was the cobas® EGFR Mutation Test (n=24, 53.3%), followed by NGS (n=10, 22.2%) and the Idylla™ EGFR Mutation Assay (n=8, 17.8%) (Fig. 2). Similarly, the most common genotyping method used in the second round was the cobas® EGFR Mutation Test, used by 13 (37.1%) laboratories, followed by NGS (n=11, 31.4%) and Idylla™ (n=9, 25.7%) (Fig. 2).

Genotyping resultsOverall, 128 (71.1%) of the tests performed in the first round reported the expected results. For case 1, 34 (75.6%) of the participating laboratories reported the expected result for the insertion in exon 20, for which the Idylla™ EGFR Mutation Assay was unable to detect this particular mutation, resulting in a WT genotype. For cases 2 and 4, over 90% of the laboratories correctly reported the expected result, while only eight (24.5%) laboratories, which used NGS, reported the exon 20 insertion in case 3. (Table 1). During the second round of the study, 103 (73.6%) of the tests performed reported the expected results. All (100.0%) laboratories reported the EGFR exon 20 insertion in case 1 and almost all (97.1%) reported the WT genotype in case 2. However, only 11 (31.4%; those using NGS) and nine laboratories (25.7%) reported the specific mutation in cases 3 and 4, respectively (Table 1).

Results obtained by the participating laboratories in the first and second rounds.

| Round 1 | Round 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Obtained result | n (%) | Genotype | Obtained result | n (%) |

| Case 1: H773-V774insGNPH Exon 20 | H773-V774insGNPH Exon 20 | 34 (75.6) | Case 1: A767-V769dup Exon 20 | p.A767-V769dup (Ex20Ins) | 7 (20.0) |

| S768I Exon 20 | 1 (2.2) | Ex20Ins | 27 (77.1) | ||

| WT | 10 (22.2) | S768I Exon 20 | 1 (2.9) | ||

| Case 2: WT | WT | 44 (97.8) | Case 2: WT | WT | 34 (97.1) |

| Not evaluable | 1 (2.2) | Ex20Ins | 1 (2.9) | ||

| Case 3: H773delinsRY Exon 20 | H773delinsRY Exon 20 | 8 (17.8) | Case 3: H773delinsRY Exon 20 | H773delinsRY Exon 20 | 11 (31.4) |

| Ex20Ins | 3 (6.7) | Ex20Ins | 1 (2.9) | ||

| L858R Exon 21 | 1 (2.2) | WT | 23 (65.7) | ||

| WT | 32 (71.1) | ||||

| Not evaluable | 1 (2.2) | ||||

| Case 4: L858R Exon 21 | L858R Exon 21 | 42 (93.3) | Case 4: H773-V774insGNPH Exon 20 | H773-V774insGNPH Exon 20 | 9 (25.7) |

| WT | 3 (6.7) | Ex20Ins | 13 (37.1) | ||

| WT | 13 (37.1) | ||||

WT: wild-type.

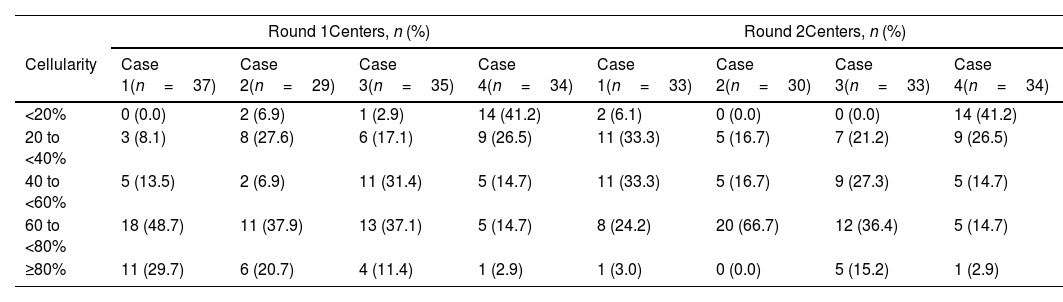

During the first round, sample cellularity was determined by 64.4–82.2% of the participating laboratories. Most (48.5–78.4%) of them estimated a cellularity of >60% for cases 1, 2, and 3. However, only six laboratories (17.6%) could estimate this percentage for case 4 (Table 2). During the second round, over 85% of the participating laboratories determined the sample cellularity, which was, overall, estimated to be >40% by most (60.5–83.4%) laboratories, except for case 4 (Table 2).

Cellularity percentage in each case from the first round.

| Round 1Centers, n (%) | Round 2Centers, n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellularity | Case 1(n=37) | Case 2(n=29) | Case 3(n=35) | Case 4(n=34) | Case 1(n=33) | Case 2(n=30) | Case 3(n=33) | Case 4(n=34) |

| <20% | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (2.9) | 14 (41.2) | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (41.2) |

| 20 to <40% | 3 (8.1) | 8 (27.6) | 6 (17.1) | 9 (26.5) | 11 (33.3) | 5 (16.7) | 7 (21.2) | 9 (26.5) |

| 40 to <60% | 5 (13.5) | 2 (6.9) | 11 (31.4) | 5 (14.7) | 11 (33.3) | 5 (16.7) | 9 (27.3) | 5 (14.7) |

| 60 to <80% | 18 (48.7) | 11 (37.9) | 13 (37.1) | 5 (14.7) | 8 (24.2) | 20 (66.7) | 12 (36.4) | 5 (14.7) |

| ≥80% | 11 (29.7) | 6 (20.7) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (15.2) | 1 (2.9) |

Table 3 shows an example of the results obtained considering the genotyping method used. In the second round, cobas® determined the correct genotype in cases 1, 2, and 4, but was unable to determine the EGFR exon 20 insertion in case 3. On the other hand, NGS correctly determined the genotype for all cases studied; however, one laboratory misreported an insertion in case 2. The variants detected by NGS in the second round are shown in Fig. 3.

Results obtained in the second round, according to the primary detection methods used.

| Obtained result | ||

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | COBAS® | NGS |

| Case 1: A767-V769dup Exon 20 | Ins20 | p.(A767_V769dup) |

| Case 3: H773delinsRY Exon 20 | WT | p.(H773delinsRY) |

| Case 4: H773-V774insGNPH Exon 20 | Ins20 | p.(H773_V774insGNPH) |

NGS: next-generation sequencing; WT: wild type.

Our study shows the results of an EQA performed in 45 Spanish laboratories across two rounds to evaluate the detection of different EGFR exon 20 insertions.

The number of participating laboratories in our study decreased from 45 in round 1 to 35 in round 2. This highlights the importance of continuity in quality programs to ensure that errors or discrepancies in the results are addressed in subsequent rounds. It further reinforces the need for systematic EQA to evaluate the accuracy of laboratory tests and verify that the most appropriate techniques are being used.

In this study, the mutational analysis of EGFR revealed that 71.1% and 73.6% of tests performed in rounds 1 and 2, respectively, reported the expected result, similar to the findings from previous years. For example, in the EQA carried out in 2016 by the SEAP in Spain, 73% of the tests reported the expected results.19

The results of our study show that a wide variety of detection methods are used in routine practice across Spanish laboratories, with PCR-based methods being more frequently used than NGS in both rounds. These results contrast with those observed in a real-world study conducted on over 67,000 patients with advanced NSCLC by Lin et al., which found that PCR use decreased to 6.5% by 2020, while NGS use increased to 64.5% by the same year.13

Previous EQA for EGFR mutations in NSCLC conducted in other countries have been published, showing a shift toward PCR and NGS in recent years. An Italian study reported a decrease in direct sequencing from 78.7% in 2011 to 14.1% in 2015, in favor of PCR-based methods. In addition, 4.3% and 1.1% of the laboratories used Cobas® and NGS, respectively, in 2015.20,21 In a similar French study, the authors found that in 2014, 33.9% of laboratories used NGS, although only 10.7% used this method in routine practice when the study was conducted.22 In the Spanish EQA in 2016, only 3.7% of the laboratories reporting results used NGS for EGFR mutational status determination.19 A higher percentage of laboratories in our present study used NGS (22.2% and 31.4% in rounds 1 and 2, respectively); however, due to the rapid shift observed in recent years toward NGS over PCR-based methods, straightforward comparisons between previously published studies20–22 and ours should be avoided.

Almost all the laboratories participating in our study were able to detect the correct WT genotype. However, discrepancies were observed in detecting the different EGFR exon 20 insertions, with the H773delinsRY being the most difficult to detect correctly. In addition, in the second round of our study, when analysing the results obtained based on the primary detection methods used, we observed that the cobas® EGFR Mutation Test was not appropriate for the detection of the H773delinsRY in EGFR exon 20. In this context, it is important to mention that only laboratories using NGS were able to report the expected result for this particular EGFR alteration.

As previously mentioned, NGS-based assays offer several advantages over PCR-based methods.23 Using NGS leads to higher detection rates of low-frequency genetic alterations, such as EGFR exon 20 insertions, which may go undetected with PCR-based approaches.23 In this context, recently published retrospective and real-world studies conducted in patients with NSCLC have shown that 40–50% of patients with EGFR exon 20 insertions identified by NGS would have been missed by PCR-based tests.24,25 Consequently, patients with incorrect molecular diagnoses may not receive effective treatment, which could ultimately lead to poor outcomes.23,24 In addition, NGS can identify novel variants, sporadic mutations, and co-mutations associated with poorer prognosis.23,26 Hence, tumor molecular profiling becomes essential for managing patients with NSCLC, especially in the context of targeted therapies.27

Despite the advantages of NGS, as observed in this study and others,28 PCR-based tests remain widely used in routine practice.23 PCR-based approaches offer a fast turnaround time13 and low cost29 compared with NGS, and are widely available.25 In addition, NGS requires experienced personnel for data analysis and interpretation.30

Finally, the results of the EQA should be discussed in the context of the updated recommendations from SEAP and the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica, SEOM). The panel of experts who participated in this study considered it essential to identify molecular alterations in EGFR, along with other well-established NSCLC biomarkers. For this purpose, they recommend using high sensitivity methods. While there are no specific recommendations for EGFR exon 20 insertions, they recommend using NGS in patients with NSCLC.31

Our study has some limitations. We were not able to collect data on the time from sample reception to molecular diagnostic results. In addition, all participating centers were from Spain, so extrapolating the results to other countries should be done with caution. Despite this, the high number of participant laboratories makes the results representative of routine practice in Spain.

In conclusion, the results of our EQA on the molecular diagnoses of EGFR exon 20 insertions in patients with NSCLC show a successful determination rate of approximately 71–74%, probably due to the fact that most laboratories in Spain still use PCR-based methods. Further EQA schemes are needed in Spain to monitor the implementation of the necessary technologies.

Ethical disclosuresAll samples were obtained with approved informed consent.

FundingThe study has been funded by the Spanish Society of Anatomical Pathology.

Conflict of interestM.B. declares providing scientific support, participating in meetings, and receiving honoraria for meetings and advisory from AstraZeneca, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, and Lilly. T.H.-I. declares receiving support from Roche for delivering several courses on quality control. A.B.E., Y.R., L.G., A.M., S.RyC., and J.L.R.P. have nothing to declare.

The authors would like to thank Janssen-Cilag SA for supporting the FOREXON Module as well as the investigators responsible for the SEAP Quality Module. They would also like to thank Víctor Latorre, PhD, at Outcomes ‘10, for medical writing support.