Introduction

Dietitians working across Europe are at the forefront of the nutritional health of the European population. The Dietitian applies the science of nutrition to the feeding and education of groups of people and individuals in both health and disease. The European Federation of Associations of Dietitians (www.EFAD.eu) and the International Confederation of Dietetic Associations (ICDA) define a dietitian as a person with a qualification in Nutrition and Dietetics recognised by a national authority1. Dietitians are therefore uniquely educated to play a role in key strategic areas which will influence nutritional health; in clinical and tertiary care, in food service and industry and in primary care and health promotion2,3. The quality of the European dietetic workforce and especially its 'fitness to practice' is a critical component of the Edinburgh (2005) and Portugal (2007) Agreements and the relevant Competent Authorities. In Europe dietitians can be found in almost every member state and must be the major human capital asset for the realisation of the European Union 'White Paper on Nutrition, Overweight and obesity - related health issues'4,5. They work, as professionals primarily with a dietetic and nutrition background although other qualifications are found to be acceptable in Member Countries6.

In June 1999, Bologna Declaration7 called for a coherent, compatible and competitive European Higher Education Area by 2010, the key objectives are:

- The adoption of a system of easily readable and comparable degrees, in order to promote European citizens' employability and the international competitiveness of the European higher education system.

- Convergence of higher education to a system of two cycles, undergraduate and graduate. The first cycle of studies, lasting a minimum of three years. The second cycle should lead to the master and/or doctorate degree as in many European countries.

- Establishment of a system of credits -such as the European Credits Transfer System ECTS- to allow transferability and access across Europe.

In 2000 the TUNING project8 was initiated to facilitate a more transparent approach across Europe for Higher Education. The Tuning process, as it is now known, requires all Higher Education to calibrate its programmes in terms of European Academic Credits and be more overt in the competences achieved as a result of the educational programme. The Education report, undertaken by EFAD, in 2002 demonstrated that educational standards for dietitians across Europe were very different9. Members of the European Federation of the Associations for Dietitians (EFAD), made a commitment in the Roskilde Resolution10 to define priorities for the harmonisation of education and practice for dietitians across Europe. As part of this commitment it was agreed to establish European Academic and Practitioner Standards for Dietetics which were accepted by all members of EFAD in 20052. These Standards or the 'European Dietetic Benchmark Statement' (EDBS) define the minimum standards of education that all dietitians working in Europe should achieve at the point of initial qualification. It recognised three different roles for dietitians working in Europe. Education standards were proposed for each role as well as for a general dietitian. The roles recognised are: Clinical Dietitian, focused on clinical nutrition and dietetics with responsibility for dietary prevention and treatment of groups and individuals in an institution or a community; Administrative Dietitian, focused on food service management with responsibility for feeding of groups of people in health and disease in an institution or a community; and Public Health or Community Dietitian, directly involved in health promotion and policy formulation that leads to the promotion food choice amongst individuals and groups to improve or maintain their nutritional health and minimizes risk from nutritionally derived illness.

A Thematic Network, to explore and improve the education of dietitians across Europe or 'Dietitians Improving Education Training Standards' (DIETS) was approved in August 2006. Initially the TN DIETS comprised of 118 partner institutions (Dietetic Associations within EFAD, other Dietetic Associations, Higher Education Institutions and Non-governmental Agencies) from 30 European countries. A key objective was to describe all areas of dietetic practice, education and training throughout Europe and develop the utilisation of ECTS (European Credit Transfer System).

In that context, the main aim of this study is to map education and practice placement training in dietetics in Europe in 2007 and again in 2009 to compare the results and judge whether progress has been made to meet the European Academic and Practitioner Standards for Dietetics2.

Methods

The Education and Practice Group of DIETS developed an online education mapping questionnaire to primarily explore adherence to the EDBS. Questions were asked about the programmes, their academic content and information about practice placements. The questionnaire contained both quantitative and qualitative questions (appendix 1). A pilot was undertaken among members of DIETS work groups and modifications made. All Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) that were partners in the DIETS Thematic Network in that period (n=70) were encouraged to complete the on-line questionnaire in March 2007 at the DIETS website in the area accessible to registered users only. In April 2009 the HEI partners of the Thematic Network were asked again to complete the interactive questionnaire to find any changes that may have occurred. The questionnaire was slightly modified by rephrasing some of the subjects taught in dietetic programmes.

Results from closed questions were analysed quantitatively using Excel. Results of the open questions were analysed qualitatively and will be reported elsewhere especially at DIETS Report 511. In some cases where there where two or more responses from an institution were obtained the data was checked to establish if two programmes eg administrative and clinical dietetics, were being represented in which case the data remained in the analysis. Where two programmes were not being represented only one data set was retained for each institution through a harmonisation of the data.

Results from the questionnaire were then compared to the dietetic education analysis by Middleton et al9, as this survey was undertaken prior to the introduction of the European Dietetic Academic and Practitioner Benchmark Statement2 and Cuervo et al6. Incomplete records and records with no answer were excluded from the analysis.

The questionnaire was only circulated to DIETS Partners, who had previously agreed to cooperate in Network activities. By answering the questionnaire and submitting the response on-line an acceptance of participation in the study and data acquisition was agreed. No formal ethical approval was sought for this study.

Results

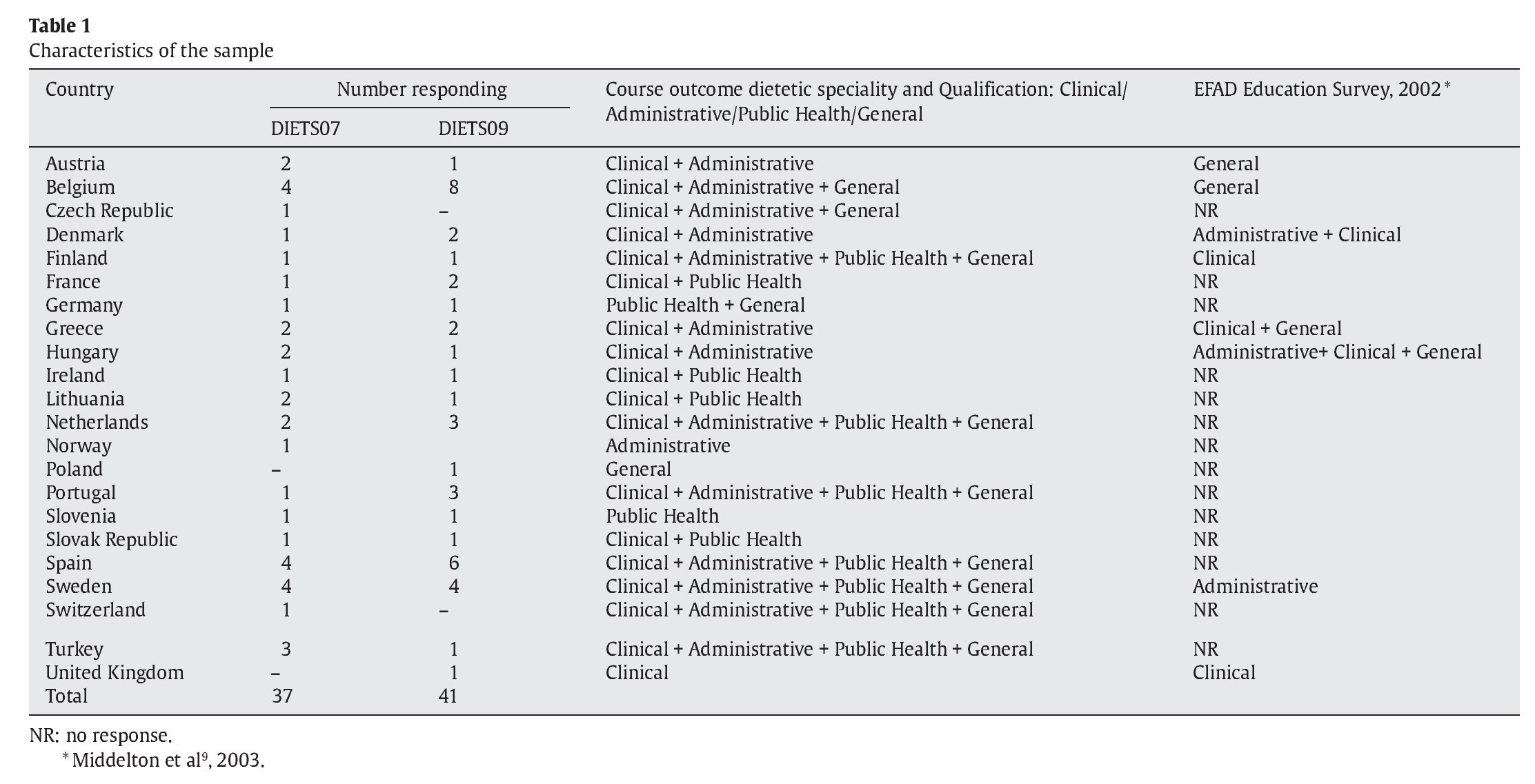

In 2007 42 questionnaires were submitted on-line. This represents a response rate 60% from the 70 HEIs that were partners. Of the questionnaires returned 5 did not put their name and country and were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 37 questionnaires, representing the DIETS07 data set, were analysed as stated in the method section. In 2009 all 41 (59% response rate) questionnaires returned were eligible for analysis, representing the DIETS09 data set. The questionnaires submitted with data missing were analysed but the quantitative analysis means have been adjusted appropriately. The databases are available on the DIETS website (www. thematicnetworkdietetics.eu). The final quantitative analysis was therefore completed on 37 questionnaires in 2007 and 41 for 2009.

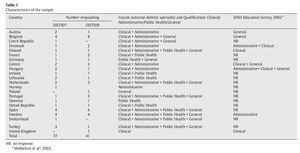

Table 1 shows the origin of the responses. The DIETS07 and DIETS09 responses show that the number of HEIs responding from each country was different and it should be noted that the some of the actual HEIs responding could be different. This was especially the case where there was more than one or two HEIs teaching dietetics in a country such as Austria, Belgium, Germany, and Spain. The data therefore is not necessarily directly comparable between the years but is indicative of the nature of the education in that particular country. It does however represent the education in the particular HEI who has responded to the survey. HEIs offer unique and characteristic programmes which may have a similar structure but vary even within a country. Therefore each HEI response is treated as a data point. There has been no attempt to present a country by country profile of dietetic education although some indicators and inferences may be drawn.

As table 1 shows HEIs have study programmes leading to qualification as a general dietitian or a clinical dietitian, administrative dietitian or public health dietitian. In some HEIs the study programmes lead to more than one qualification. The diversity of the programmes did not change from 2007 to 2009. Although in comparison to the Middleton et al9 survey the diversity of dietetics of programmes leading to different areas of employment in Europe for qualified dietitians has increased. In many countries the general dietetic category allows the dietitians to specialise on qualification or to assume a more holistic approach and adapt to the needs of the service. Diversity is therefore an indicator of the responsiveness of the profession to meet the challenging and different needs of the society and culture in which they find themselves.

Almost all students are trained to give nutritional advice to both groups and individuals (100% and 94%, respectively) and counsel individuals with dietary related illnesses therapeutically in the community (84%) and hospitals (86%). They are also trained to take responsibility for feeding groups of people (83%). 71% of students are trained to manage food services.

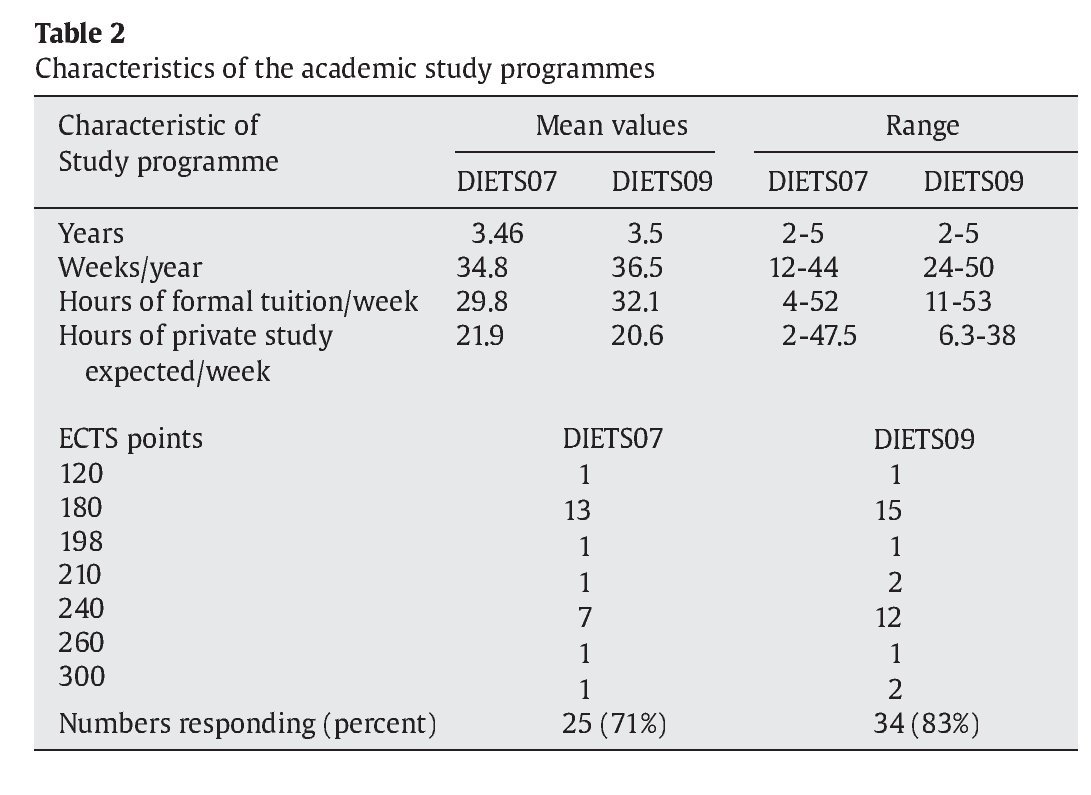

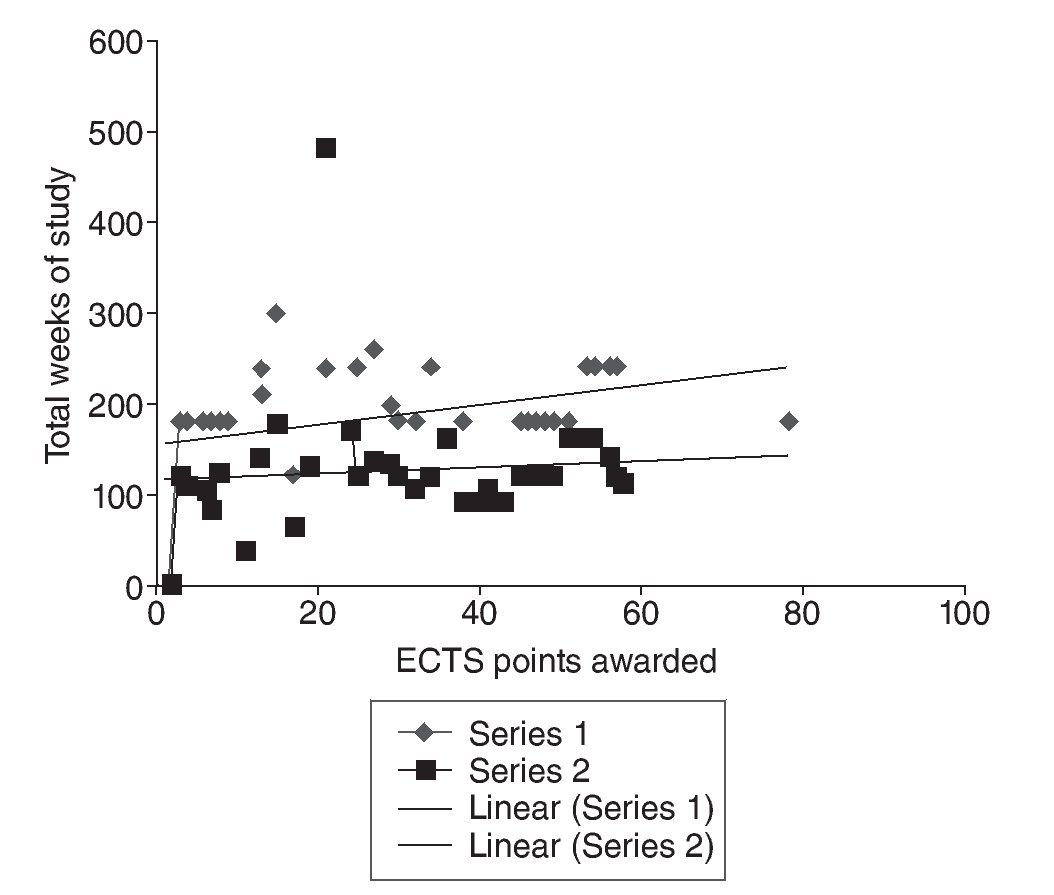

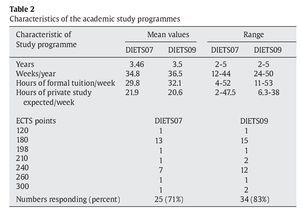

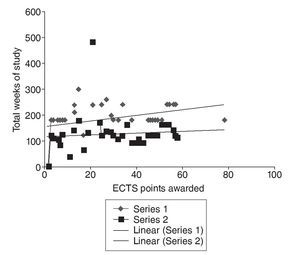

Table 2 shows that the mean duration of study programmes and other characteristics of the programmes, have not altered between the two survey periods, for example the average programme length remains at about 3.5 years, with a range from 2 years in France to 5 years in Finland. However, it is also important to know the number of weeks a year that the study programme includes, that ranges from 12 weeks a year in Czech Republic to 44 in Lithuania. The most reasonable way to measure the academic load of a study programme may be by using the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS). Information about ECTS points were provided by 25 (71%) and 34 (83%) of HEIs in 2007 and 2009 respectively (fig. 1). The values provided indicate enhanced use of the ECTS system but also indicate, despite the increase, that some HEIs still do not calibrate their courses. Students have to gain between 120-300 ECTS for completion of study programmes, although in 2009 more programmes were reported requiring higher ECTS points for completion. According to the EDBS all study programmes for dietitians should at least lead to a first cycle degree, which carries a minimum of 210 ECTS. In DIETS 2007 15 (60%) of HEIs reported below 210 ECTS but in 2009 only 17 (41%) HEIs had a study programme of less than 210 ECTS.

Figure 1. There is a poor agreement between the ECTS points awarded and the length of time of study in some cases.

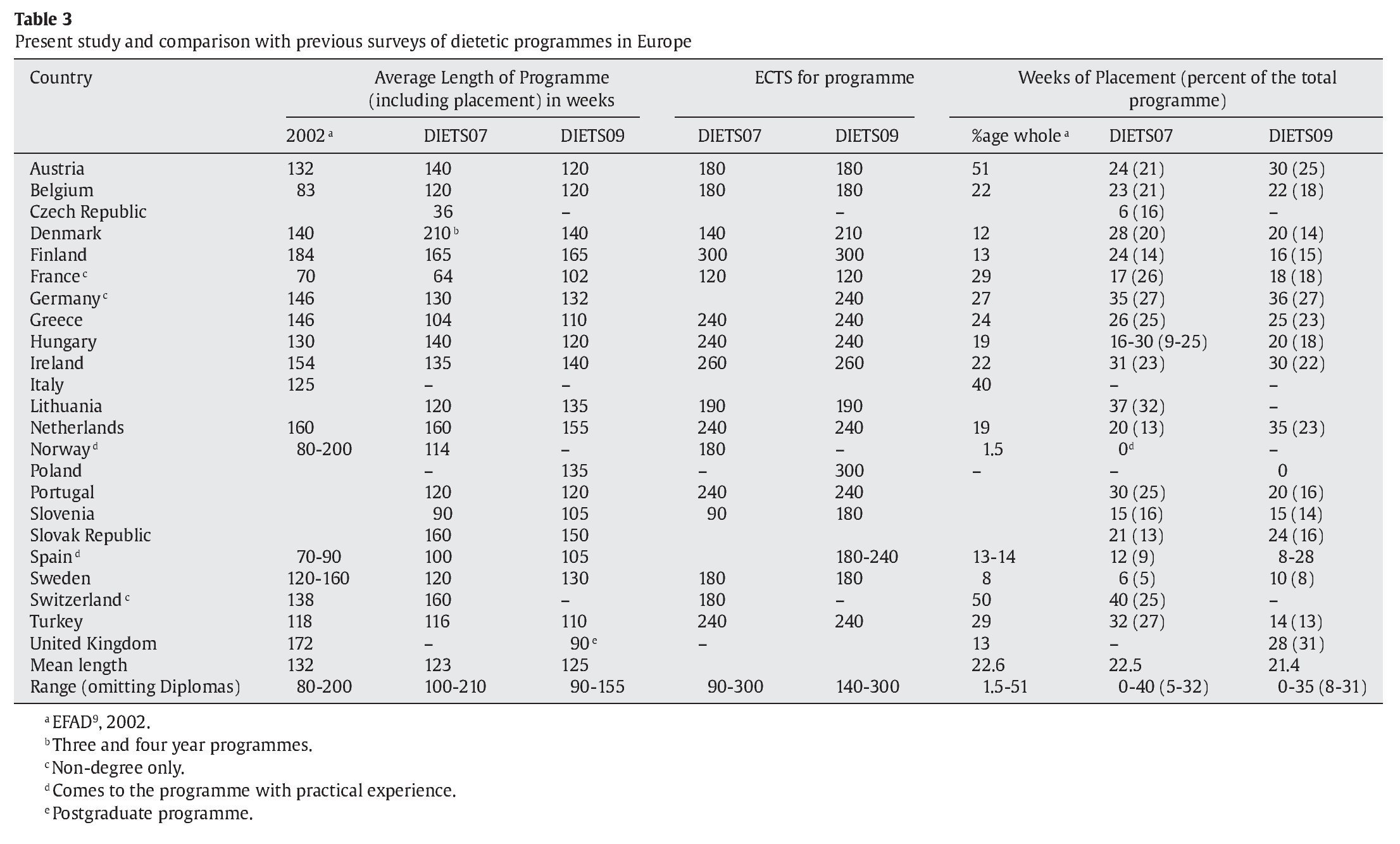

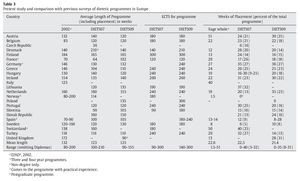

Table 3 provided more detailed information about the programmes in each country where at least one HEI has responded. Where several HEIs have responded an average length of programme has been calculated. As the same HEI has not necessarily responded to the questionnaire in both survey periods there is some variability from one survey year to another which is attributable to the HEI and not necessarily attributable to a change of education within that country.

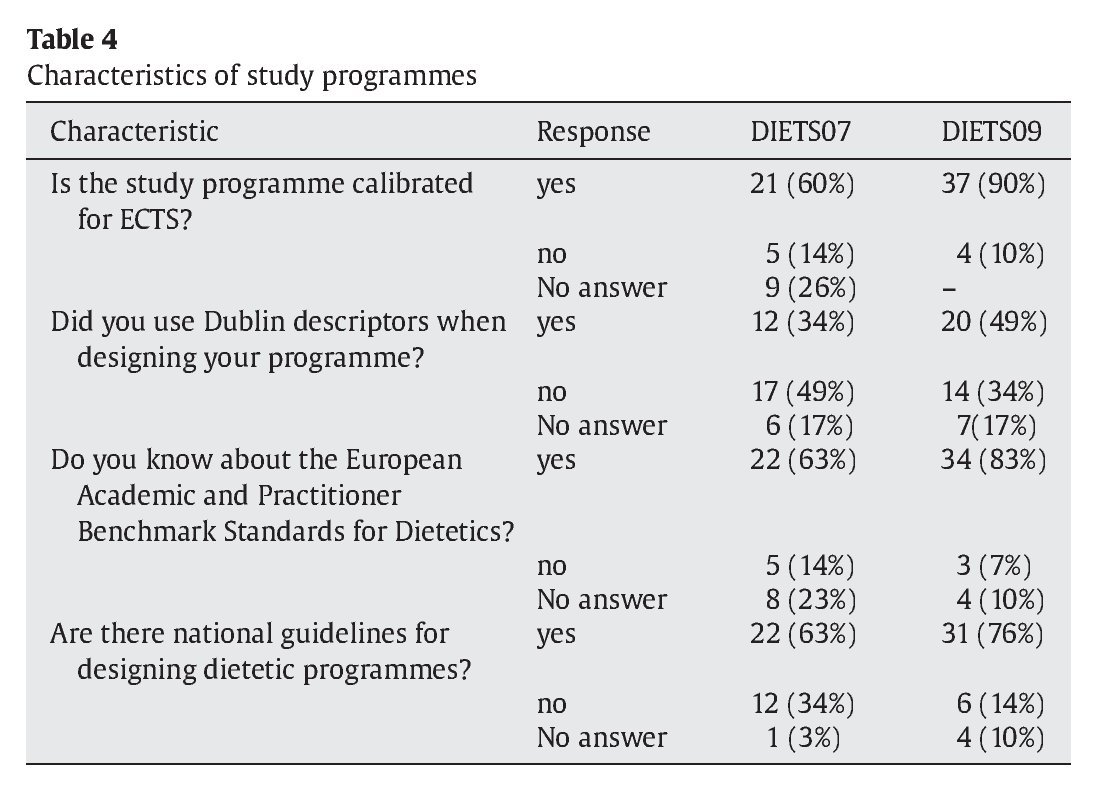

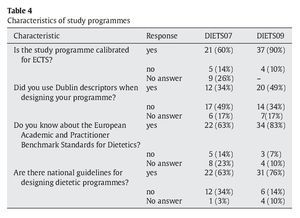

When designing programmes it is important to use the available guidance and ensure that programmes adhere to the best possible standards to ensure the transparency of education a recommendation of both Bologna7 and Tuning8. Table 4 shows that over the two year period HEIs reported increased awareness and use of ECTS, Dublin descriptors and the European Benchmark Standards for Dietetics. Also National Guidelines for dietetic programmes are increasingly available and used for programme design.

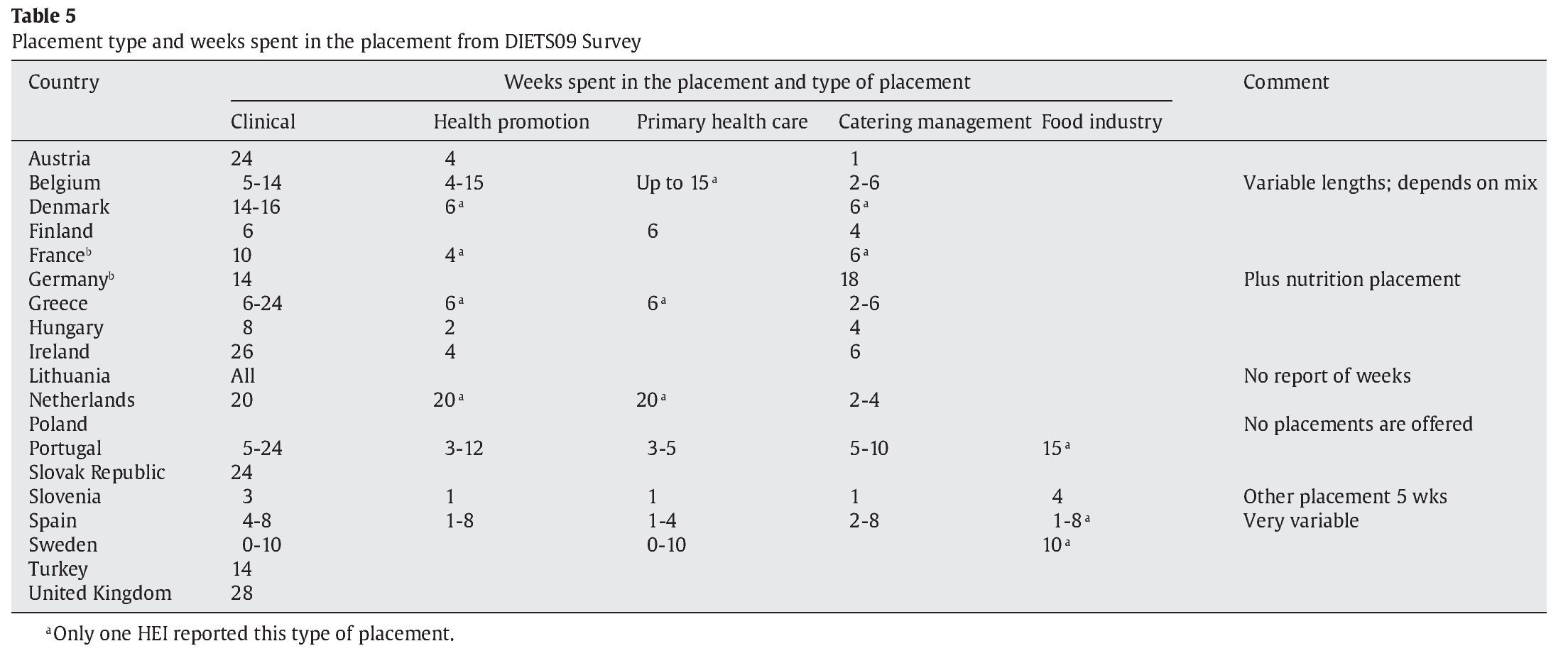

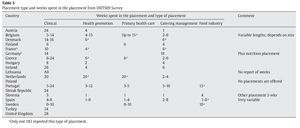

The placement period is of particular importance to professional education in dietetics and the EDBS stipulates that the equivalent of 30 ECTS credits or a minimum of 50 % of an academic year should take place in practice. If the average length of a dietetic programme in Europe is about 35 weeks this would equate to a minimum of 17 weeks of placement in a typical programme (table 2). The mean of the placements 22.5 and 21.4 weeks in 2007 and 2009 respectively appear to be well over this requirement. But table 3 shows that in seven countries (Czech Republic, Norway, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Turkey) students appear, from the HEIs responding to the surveys, to undertake less than 17 weeks of placement. In Finland the students arrive on the programme with practical experience that is acceptable for their programme of studies and therefore do not need to undertake further practical experience. Table 5 shows the detailed results from the DIETS09 survey which is very similar to DIETS07 data. It can be seen that placement learning could be achieved in five different placements which all represent fields of employment for dietitians working in Europe. Typically table 5 shows that the most usual placement is in the clinical environment. Most HEIs offer a placement in either health promotion or primary health care and in the catering area. Some also offer a placement in the food industry. Some HEIs offer the opportunity for students to choose their own placement environment. Where more than one HEI reported from a country it can also be seen that different HEIs have variety in the length a placement and that some HEIs offer a number of alternative placements. For example in Portugal only one HEI offers placements in the food industry of the three that responded. In Sweden a placement in the food industry or catering management is allowed in only one HEI. Offering different placements may allow the student to develop their learning and skills in a particular environment. This may be more fitting to the type of employment they will potentially seek. Overall students will undertake a period of practice placement which is unique to that study programme in that country.

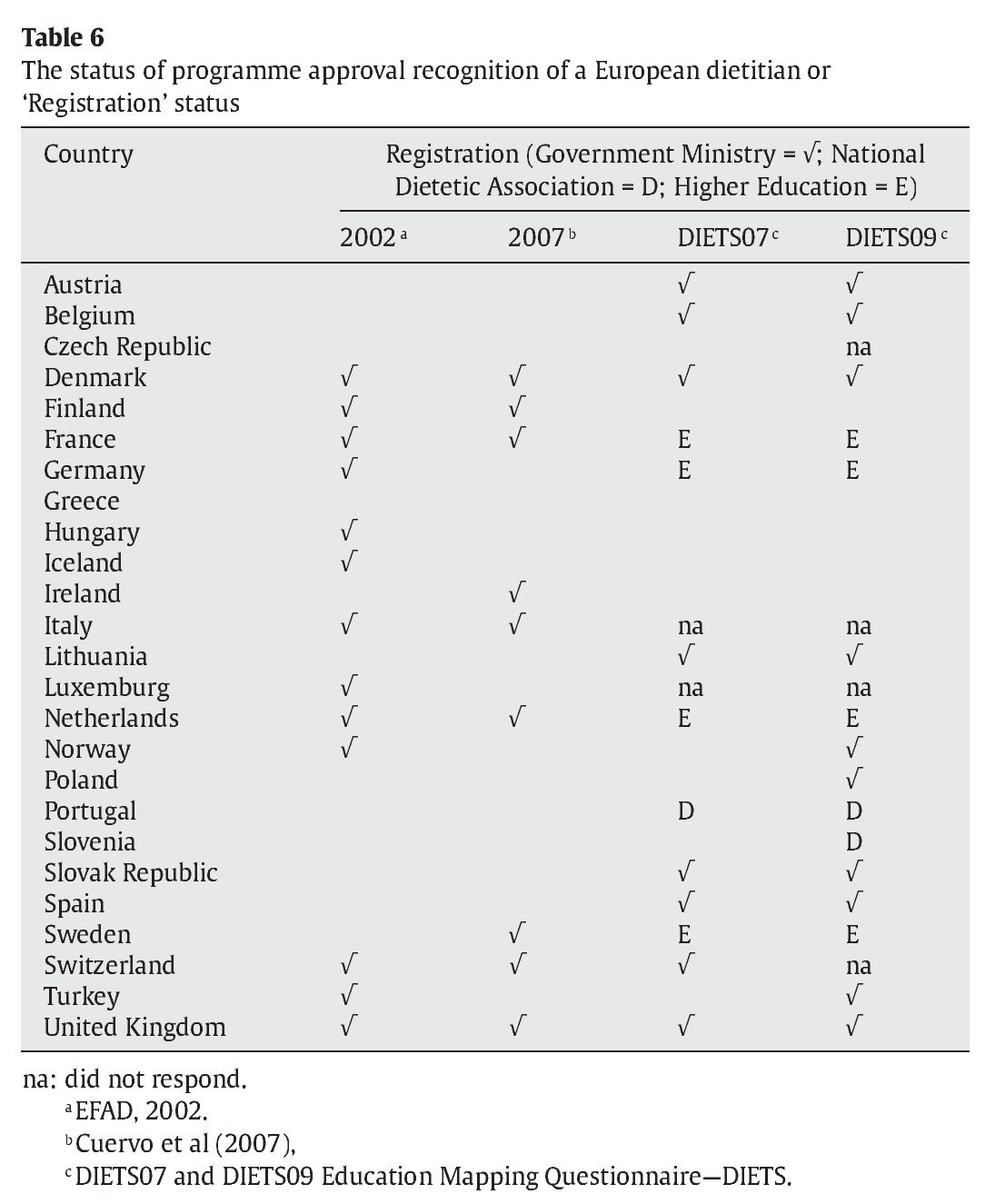

The graduating student can expect to have studied a programme that is of a particular standard and recognised for future employment as a dietitian. Table 6 indicates the national authority which has set the standard. It was not always clear from the data whether the standards are set by the Government through a Ministry or by a national quality assurance system for education or by the National Dietetic Association. All may be referred to as conferring 'registration' as they all will require that a particular standard is met. In this paper the categories of 'registration' have been labelled by the authority stated in the surveys that confer the 'registration' ie a government ministry or a national education quality assurance system or a professional dietetic association.

Different paths to 'registration' and recognition of dietetic qualifications may lead to different surveys producing different results and this is evident in table 6.

Over the study period 2007-2009 table 6 shows that four countries now report that a national standard has been set. In Norway, Poland and Turkey it is reported, by the HEIs responding, that a government ministry has now set a national standard whilst in Slovenia the standard set is from the National Dietetic Association. At least five countries, in this survey period, do not yet appear to have any national standard. Each HEI imposes its own informed standard of education for dietitians in that country albeit guided by national dietetic associations.

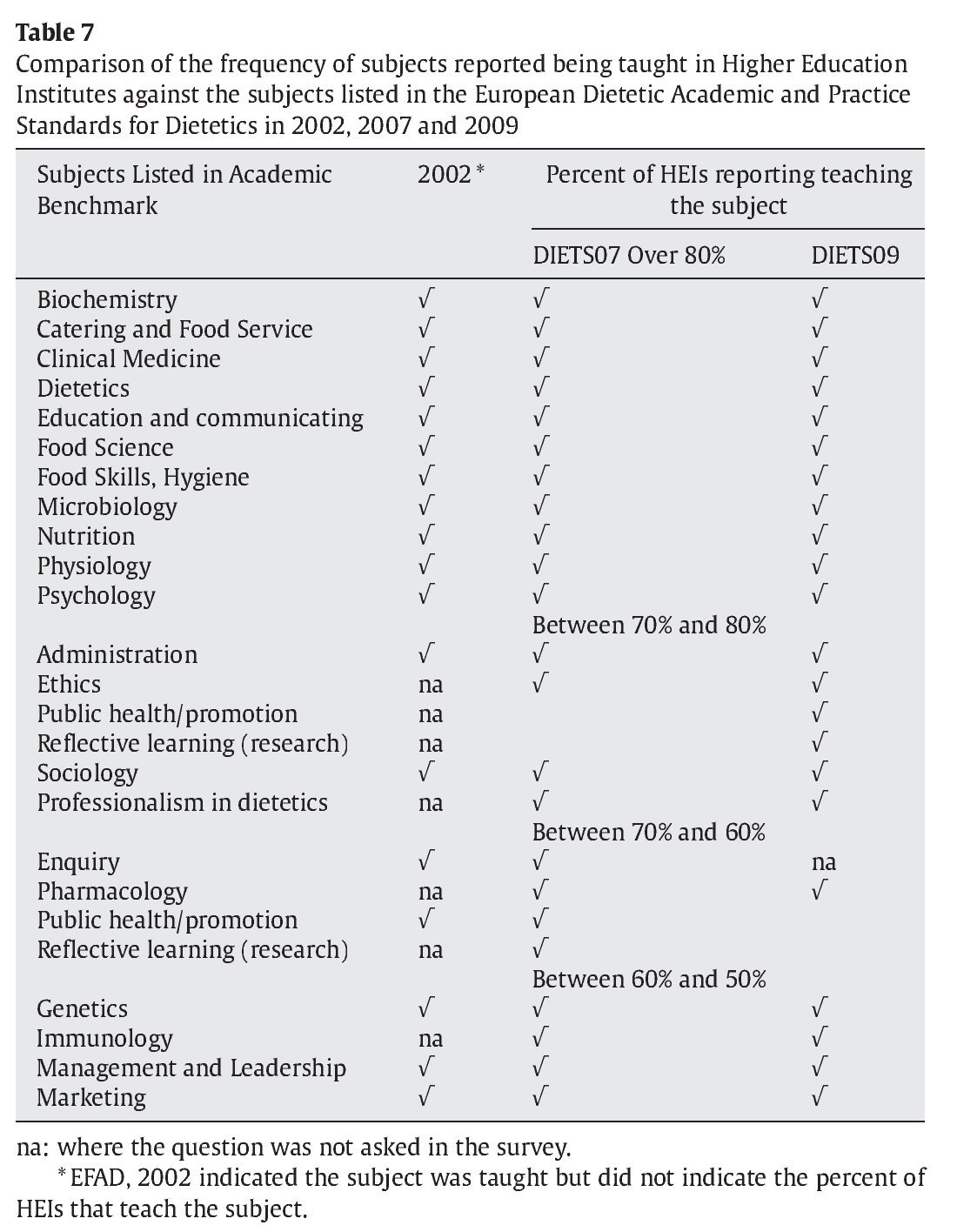

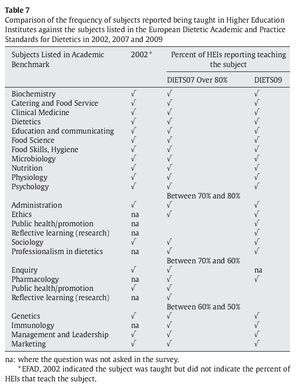

The European Academic and Practitioner Standards for Dietetics2 state the subjects that are expected to be included within a dietetic programme in Europe. The benchmark includes subject knowledge, understanding and associated skills that are essential to underpin informed safe and effective practice of dietetics. Table 7 summarises the percent of HEIs who reported that these subjects are included and taught in their programmes leading to a qualification in dietetics. Of these subjects, biochemistry, catering and food service, clinical medicine, dietetics, food skills and hygiene, microbiology, food science, education and communication, nutrition and physiology are taught in HEIs.

Subjects such as administration, ethics, sociology and professionalism of dietetics are taught in 80% of HEIs. While subjects such as enquiry, pharmacology are reported in 70% and genetics, immunology, management and leadership and marketing in less than 60% of reporting HEIs. Only two subject areas were reported as being taught in more HEIs between 2007 and 2008 and these are public health/promotion and reflective learning (research) both moving from less that 70 % to between 70-80% of HEIs. In the EFAD study9 some subjects were not reported on such as ethics, public health/promotion, reflective learning (research), and professionalism in dietetics, pharmacology and immunology. It is therefore not possible to draw any conclusions as to whether between 2003 and 2009 these subjects were introduced or are now being increasingly taught. Additionally, HEIs teach subjects that are not specifically mentioned in the benchmark statement, like entrepreneurship, quality assurance, biostatistics, toxicology, mathematics, general economics and reflective learning (research).

Some HEIs reported that there are some subjects mentioned in the benchmark that are less important than others. The less important items are: management and leadership, economics and legislation, catering and food service management. While some HEIs report that some items are still under-represented, such as diet therapy, entrepreneurship, hygiene, logistics, epidemiology, statistics and research, quality care and the role of dietitian in industry. Clearly there is no complete consensus across Europe on all subjects that should be in a dietetic curricular despite the EDBS.

Discussion

The total number of dietitians in EFAD membership is about 29,000. The Action Plan for Nutrition in Europe12 sets out a new European agenda for health with particular emphasis on improving the nutritional status of the people of Europe. Given the comparatively limited dietetic workforce in Europe the challenges that face the Profession could be said to be four-fold:

- The professional obligation to teach others how to promote effective nutritional and dietary change and best practice.

- Raising the professional leadership profile primarily through lifelong learning.

- Providing and promoting the tools and expertise necessary to develop the evidence base required for its key role in improving nutritional health.

- A shared and transparent, quality-assured self-regulation role within professional associations to augment that of regulators.

Higher Education in Europe must therefore rise to the challenge and provide dietetic programmes which are fit for purpose and fit for practice. The Thematic Network DIETS was funded to inform that process. The DIETS project has succeeded in bring together HEIs and the National Dietetic Associations and their members to work together to promote change. Through the mapping questionnaires in 2007 and 2009 and the reports DIETS Report 213, DIETS Report 314 and DIETS Report 511, a picture emerged of the productive working achieved over 2006-09. But the DIETS07 and DIETS09 demonstrate that there is still diversity in the education for the new professional dietitian in Europe. It is right that each country should set its own requirements for its dietetic workforce but as reported there are still HEIs in eleven countries which report that the national government is not involved directly in setting dietetic standards.

It is encouraging to see that the majority of countries provide a diversity of dietetic qualifications as dietitians can influence the nutritional supply of food, its promotion, food service/catering and modification for health in a wide range of employment opportunities. Only one country, the UK, offers a narrow range of qualifications. However if the newly qualified dietitian is to take full advantage of jobs that will influence nutrition then programmes must not only incorporate practical placements but also suitable and appropriate subject knowledge. The DIETS09 survey showed that clinical and catering management are placements encountered by nearly all students. But areas such as placements in the food industry are offered by only a few HEIs. While students can be offered the choice of placements maintaining the quality of the learning experience of each placement may be problematic especially as they increase in number and variety11,13,14. Further it is not clear if all students experience a learning opportunity in health promotion or primary health care as some HEIs report that these placements are optional. If the WHO Action Plan12 and the strategy to tackle obesity4 are to be effective then public health/health promotion must be central to any dietetic education programme. Encouragingly more HEIs now teach this subject in 2009 than previously but up to a third of HEIs report that they are still not doing so.

The difference in length of study programmes and placements which is demonstrated in table 3 is probably a reflection of the HEIs responding to the different surveys. Overall the mean length in weeks of programmes and placements are very similar between DIETS07 and DIETS09. The data shows that since 20029 the diversity of the length of programmes has narrowed (indicated by the ranges of weeks spent on each programme) except for France, Slovenia and Spain where HEIs report that the weeks have increased. This could be a direct effect of the introduction of the EDBS in 20052. The placements also show some changes between 2007 and 2009 and in particular the Netherland HEIs report that 23% of their programmes are now spent on placement compared to 13% in 2007. While Denmark, France and Turkey showed a decrease in the percent of their programmes spent on placement. The HEIs in Spain continued to show the most variation in the length and percent of their programmes spent in placement despite having government oversight/recognition of their programmes and hence national standards.

All countries reported ECTS calibration of their programmes except for the Czech Republic, Germany, Slovak Republic, Spain and the UK although by DIETS09 all but the UK and Slovak Republic had declared ECTS calibration. Hungary and Slovenia had increased their calibration count and Germany and Spain all calibrated at over 180. Overall 18 countries now had programmes (DIETS09) at or above the credits recommended by the EDBS compared to 11 in DIETS07. There may be many factors which influenced this ECTS recognition however it is known that the EDBS has been an important reference document when considering changes to dietetic programmes. Interestingly the weeks of taught programmes do not easily reflect the calibration to ECTS points. Both Farkas et al15 and Plasschaert et al16 report that this is not an unexpected finding particularly as it relates to practice placements. The intensity of the study can vary between years of programmes and also the subject matter and for this reason there is often little relationship. However this is an area where further study is warranted especially for placements where practitioners teaching students need to be confident that the learning environment is providing the intellectual challenge required or necessary.

The EDBS should also be influential in the subject curricular which HEIs develop as well as other documents. The data from DIETS07 and DIETS09 demonstrate that not only was the EDBS more frequently referred to between the two survey periods but also the Dublin descriptors and national dietetic guidelines. The DIETS Network has been influential in bringing these very important benchmark standards to the attention of HEIs.

Subjects such as pharmacology and immunology are increasingly relevant to healthcare practitioners and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), an association of clinicians, researchers and allied health professionals is dedicated to improving the health of people affected by allergic diseases17. In a recent 2010 conference presentation, Zuberbier (Secretary General of the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network) said that some 90% of sufferers do not get the right treatment and some countries in Europe are more effective in treatment than others18. Nutrition and dietary manipulation is an important cornerstone of treatment in allergic conditions and all dietitians should have an understanding of immunology. It is therefore very disappointing that less than 60% of HEIs in both DIETS07 and DIETS09 report this as a subject in their curricular. Genetics, Management and leadership and Marketing are also subjects, stated in the Benchmark statement, that appear only in 50% of curricular. If dietitians do want to take on a leadership role, as suggested previously, than teaching these subjects at pre-qualification level must be a priority. Subjects such as reflective learning (research) and public health/health promotion do appear to be taught in more HEIs responding to DIETS09 than DIETS07. This is encouraging and critical for developing a profession able to promote the tools and expertise necessary to develop not only a professional evidence base but also evidence of effective intervention for better nutrition.

However it is still disappointing that such important topics as sociology, professionalism and pharmacology do not appear to be taught in at least 20% of HEIs responding to the surveys. The promotion of a curriculum which is contemporary and anticipatory of the roles that dietitians will play in the future is the responsibility of both the National Dietetic Associations and the HEIs working together and the Thematic Network DIETS has begun this committed dialogue and partnership working.

As with any survey that is longitudinal in nature and involves repeated questioning the responders may differ between time points. Indeed this was the case in this survey and it is particularly noticeable that where more than one HEI is present in a country the data sets between years may be difficult to interpret. For example in the DIETS07 survey only 4 HEIs responded from Belgium whereas in DIETS09 8 responded. Similarly some of the HEIs responding ran 3 year programmes which were not yet at degree level or 5 year programmes which might be said to be at postgraduate level. It was therefore difficult to handle the data as a coherent and robust set. Additionally where there was no unifying set of standards in a country the diversity of the response was apparent. Therefore the data must, in many circumstances, be taken as indicative and inferential. That is not to diminish or discourage discussions especially on the nature of the subjects being taught in HEIs and the appropriateness of the type of placements, their length, contribution to the overall programme and their quality assurance.

Conclusions

Most HEIs meet the Benchmark criteria of having a first or second cycle degree and using ECTS for calibration. Although the EDBS indicated that the study programmes for dietitians should have a minimum of 210 ECTS currently only 50% of HEIs meet this requirement but this indicates an improvement over the two year timeframe. All but two countries in Europe that teach dietetics have a practical component in their study programme despite this being a recommendation for all programmes. The relative time spent on practice placement learning is on average in agreement with the EDBS. While there is seen to be some increase of subjects taught in European dietetic programmes many HEIs are continuing not to include the full breadth of subjects accepted by EFAD. This means that there is a potential to jeopardise the ability of the newly qualified dietitian to meet the challenges faced in the workplace. More active engagement of national governments and their ministries in regulation through setting dietetic standards may help support this change. The involvement of the Thematic Network DIETS in promoting change is evident from the above where considerable differences between 2007 and 2009 have been found. But further changes in academic curricula will require a considerable longer period of time than 3 years especially if national standards are to be amended.

If the dietetic workforce in the future is going to be flexible and move across borders more support at national level must be sought19,20 by the national professional associations and EFAD. The European Academic and Practitioner Benchmark Standard for Dietetics2 and now the European Dietetic Competences and their Performance Indicators21, prepared by the DIETS Network, will continue to set standards across Europe and provide the platform for this engagement. This should lead to a shared and transparent, quality-assured self-regulation role within professional associations which can and should augment that of national regulators. Further research and surveys in the future will contribute to the knowledge base on the education and practical experiences of dietitians about to enter the profession in Europe. Using this information to positively influence the preparation of European dietitians will contribute to a profession which is fit for purpose and ready to improve the nutritional health of the peoples of Europe.

Aknowledge

The authors would like to thank the HEIs who so kindly gave of their time to answer the online questionnaires.

Fundings

The funding of the survey and project has been through the generous Socrates Project grant: 229180-CP-1-2006-1-UK-ERASMUS-TN.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

*Corresponding author.

e-mail: adelooy@plymouth.ac.uk (A. de Looy).

INFORMACIÓN DEL ARTÍCULO

Historia del artículo:

Recibido el 21 de junio de 2010

Aceptado el 19 de julio de 2010