The intensity of the home care interventions for dependent older people offered in Spain may not be sufficient to help keep older people living at home, being the institutionalization in a nursing home (NH) an unavoidable consequence.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the effect of intensification in home care interventions on users with grade II or III dependency, as well as training for their informal caregivers in order to delay or avoid their institutionalization in a NH.

MethodsA randomized clinical trial with two parallel arms and blinded assessment will be conducted at the community level in two municipalities in Catalonia (Spain). The study will include those older people (aged 65 and over) living in the community, with degree II or III of dependency, users of the public home care unwilling to be institutionalized and with a main informal caregiver in charge, who will also participate in the study. The assessments will be performed monthly up to 15 months, when the intervention will be finished. The main outcome will be the time until the willingness for admission to a NH. Secondary variables will be composed of sociodemographic, health, psychosocial, resource use, and follow-up variables. A multivariate Cox regression model will be carried out to estimate the effectiveness of the intervention.

DiscussionA multimodal home care intervention could improve the health and psychosocial status of dependent people and their informal caregivers and facilitate their permanence at home.

Trial registrationNCT05567965

La intensidad de las intervenciones del servicio de atención domiciliaria (SAD) para personas mayores en situación de dependencia que se ofrece en España puede no ser suficiente para ayudarles a permanecer viviendo en su domicilio, siendo la institucionalización en una residencia geriátrica una consecuencia inevitable.

ObjetivoEvaluar el efecto de una intensificación en las intervenciones del SAD en personas con grado de dependencia II o III, así como una formación de sus personas cuidadoras no profesionales para retrasar o evitar su institucionalización en una residencia geriátrica.

MétodosSe realizará un ensayo clínico aleatorizado con dos brazos paralelos y evaluación ciega a nivel comunitario en dos municipios de Cataluña (España). El estudio incluirá a aquellas personas mayores (de 65 años o más) que vivan en la comunidad, con grado II o III de dependencia, usuarias del SAD público, sin voluntad de institucionalización y con una persona cuidadora no profesional principal a cargo, quien participará en el estudio. Las valoraciones se realizarán mensualmente hasta los 15 meses, cuando finalizará la intervención. La variable principal será el tiempo transcurrido hasta la voluntad de ingreso en una residencia geriátrica. Las variables secundarias se diferenciarán entre sociodemográficas, de salud, psicosociales, de uso de recursos y de seguimiento. Para estimar la eficacia de la intervención se realizará un modelo de regresión de Cox multivariante.

DiscusiónUna intervención multimodal podría mejorar el estado de salud y psicosocial de las personas dependientes y sus personas cuidadoras no profesionales y facilitar su permanencia en el hogar.

A low birth rate and longer life expectancy are transforming the age pyramid of the European Union; probably the most important change will be the marked transition to a much older population structure, a development that is already evident in several member states.1 The life expectancy of Spaniards is among the highest in Europe2 and according to data from the National Statistics Institute (INE), older people (65 years and over) form 20.1% of the total population.3 The older adult population generally suffers comorbidity and associated conditions that impact on their daily lives,4 resulting in an increasing demand for long-term care.5

Dependent older people require a level of care that in many cases cannot be provided at home, leading to a nursing home (NH) admission.6 One in four older adults will spend a period of their lives in a NH, and the need for such care will persist until death,4 since institutionalized older people have the highest rates of comorbidity, frailty and disability.7

The World Health Organization (WHO) stated that the role of NHs is to ensure that users with a significant loss of functional capacity can experience healthy aging by optimizing the individual's physical or mental capacity trajectory or compensating for the loss of functional capacity by providing the necessary support and environmental care to ensure their well-being. Therefore, rather than simply focusing on meeting the basic survival needs of older adults, the ultimate goal of NHs should be to maintain the functional capacity of residents.8

However, the literature proves that these conditions are not always fulfilled. A current systematic review shows a dramatic functional decline in geriatric residents one year after admission to the NH, ranging from 38% to 50%.9 In addition, according to recent surveys, more than 80% of older people prefer to live at home.10,11 Both of them are robust indications that the current model of care should be oriented toward prolonging the autonomy of the older people so that they remain as long as possible in their homes and delaying their admission to NHs.

At the same time, the demand for non-professional care is likely to increase in the coming decades.12 Informal caregivers usually are family members, neighbors, close acquaintances or other significant individuals who provide unpaid daily assistance to a family member or a dependent older adult who cannot care for themselves.13 They play a strategic role in the daily activities of their dependent care recipients; however, informal care negatively affects the caregiver's work productivity and their health; in fact, informal caregivers report a significant lack of support and demand education related to the functional care.14,15 Over 50% of informal care in Spain is high-intensity care, that is, the caregiver carries out more than 20h per week of caregiving.16

To counteract these negative effects, governments are promoting a home-help service. In 2007, a new System for the Promotion of Personal Autonomy and Assistance for Persons in a Situation of Dependency (SAAD) was established in Spain.17 This service provides a set of activities aimed at providing personal care at home to people with difficulties in carrying out activities of daily living or lacking personal autonomy, through public contracting. In Catalonia, the service is provided in two modalities: a modality of care for people in a situation of dependency (SAAD Dependency) and another modality of care for people in a situation of vulnerability or social risk. In 2018, according to IMSERSO data,18 just over 10 million hours per year of SAAD Dependency were offered in Catalonia, translating into an average intervention intensity of fewer than 20min per day to each user. These statistics are far removed from those of some Nordic countries such as Denmark, which during the same year offered an average intervention intensity of close to 180min per day and where the rate of geriatric residents over 65 years of age is decreasing year after year.19

The intensity of the SAAD Dependency offered in Spain, and specifically in Catalonia, may not be enough to help keep the older people at home and delay institutionalization in a NH, but an intensification of the intervention could improve the health and psychosocial status for the dependent users, as well for their informal caregivers, and facilitate their permanence at home. Therefore, the main aim of the study is to evaluate the effect of an intensification of the SAAD Dependency intervention in users with grade II or III dependency, as well as training for their informal caregivers to delay or avoid their institutionalization in a NH.

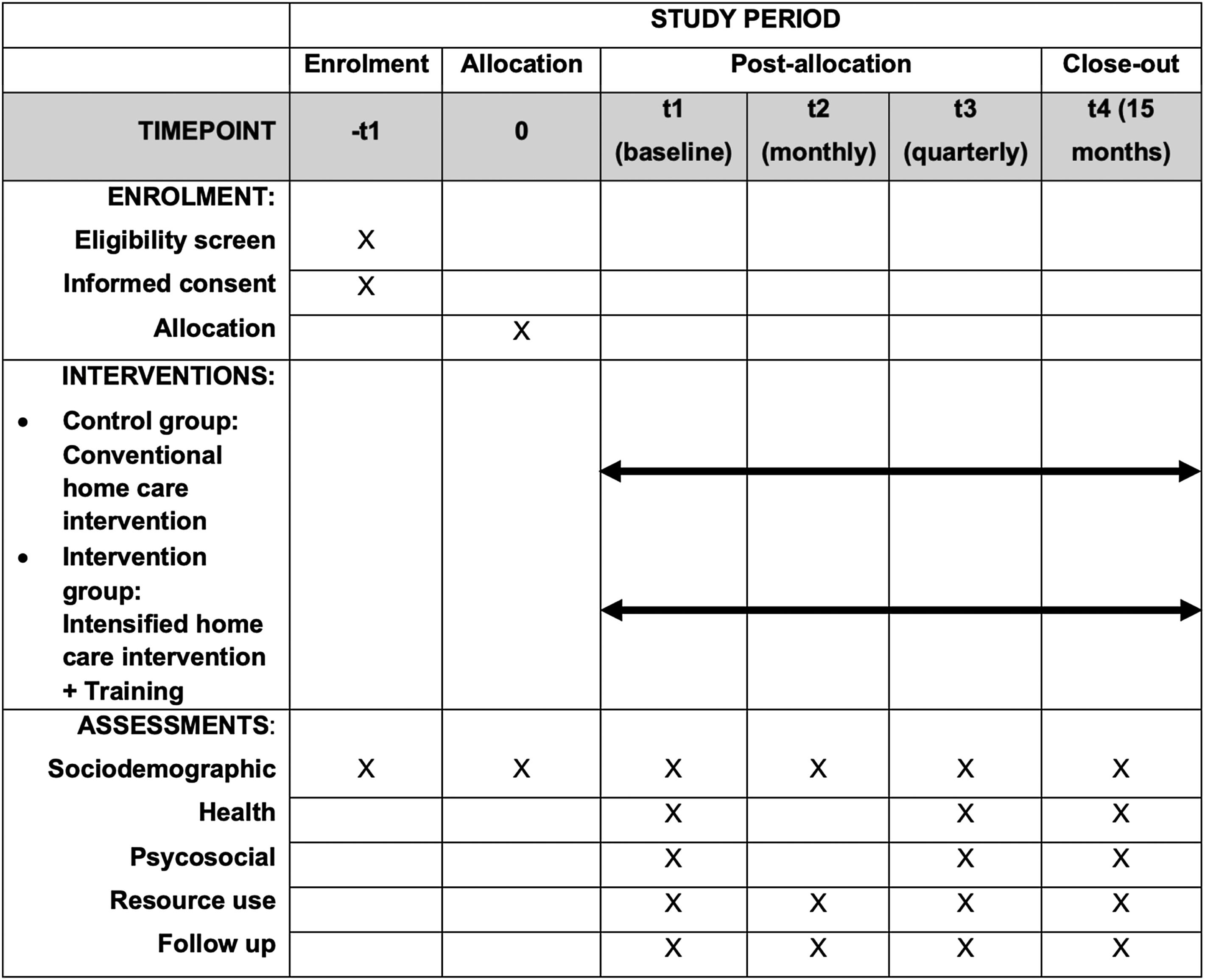

MethodsStudy design and settingA randomized clinical trial (RCT) with two parallel arms and blinded assessment will be performed during 15 months following the recommendations of the Consolidate Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT).20 The protocol of the study is registered in Clinical Trials (NCT05567965) and written following the guidelines for interventional trials (SPIRIT).21 The RCT will be carried out at the community level in two municipalities in Catalonia (Spain): Reus and Manresa. The intervention will be conducted on an individual basis by SAAD professionals, offered by the contracting companies working with the different municipalities, and will be supervised with follow-up by the research team. Fig. 1 outlines when each study component occurs: enrolment, interventions, and assessments.

Sample sizeAccepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of less than 0.2 in a bilateral contrast, 80 intervened people with a total of 63 institutionalized cases and 80 control people with a total of 63 institutionalized cases are needed to demonstrate a relevant effect of the intervention (hazard ratio=1.8) on the time to institutionalization request. For this reason, a sample size of 160 participants (80 in each study group) is established. If it is assumed that the institutionalization request rate in the control group at 2, 10 and 15 months after the SAAD intervention will be 5%, 10% and 99%, then the expected effect of the intervention will result in rates of 0%, 2% and 98%, respectively. A loss-to-follow-up rate of 25% has been estimated. These calculations have been performed with the GRANMO program.

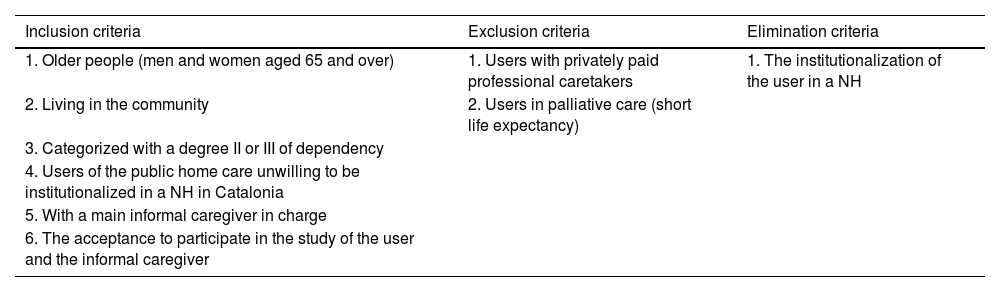

Recruitment and participantsParticipants, users and their informal caregivers, will be recruited through the city councils and companies offering the SAAD of the participating municipalities. Once the potential participants have been identified, they will be asked for authorization to provide their contact details to the principal investigator, who will contact them by telephone to offer the possibility of participating in the study and send them the participant information sheet with the details of the study. Those who agree to participate must sign the informed consent form and be informed that they have a waiver form so that they can withdraw from the study at any time if they wish. The eligibility criteria for study participation are detailed in Table 1.

Trial inclusion, exclusion and elimination criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Elimination criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Older people (men and women aged 65 and over) | 1. Users with privately paid professional caretakers | 1. The institutionalization of the user in a NH |

| 2. Living in the community | 2. Users in palliative care (short life expectancy) | |

| 3. Categorized with a degree II or III of dependency | ||

| 4. Users of the public home care unwilling to be institutionalized in a NH in Catalonia | ||

| 5. With a main informal caregiver in charge | ||

| 6. The acceptance to participate in the study of the user and the informal caregiver |

The protocol of this clinical trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia (UVic-UCC) with registration number 220/2022. All participants will be informed verbally during the process of inclusion in the study by one of the investigators and will be given the information sheets with all the detailed aspects and the informed consent. The participants’ identity in the study documents will be coded, and only authorized persons will have access to identifiable personal details if data verification procedures require inspection of these details. The data obtained will be stored in an electronic database with access restricted to the research team.

Randomization and blindingAn external person to the research team will generate a randomization sequence by computer, using random blocks of variable size. Assignment to the control or intervention group will be made once the user and his informal caregiver have been included in the study, by means of numbered sealed envelopes, following a procedure of concealed allocation of the participants. During the study, the only people who will be blinded will be the evaluators so that they have no influence on the assessments made according to the group to which the participants being assessed belong. Due to the nature of the intervention, it cannot be guaranteed that the participants will not deduce to which group they belong. In addition, the team of professionals who will do the intervention cannot be blinded either.

ProcedureThe description of the intervention has been made following the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TiDier)22 guide to adequately describe all the aspects related to the intervention and to favor the replication of the study.

The professional profiles that will implement the intervention will be social workers, family workers (home help assistants), home cleaning assistants, SAAD coordinators and, when appropriate, other social services professionals, following the regulations governing the service. The duration of the intervention, both in the control group and in the intervention group, will be 15 months or until the user is admitted to a nursing home:

Control group: conventional home care interventionParticipants will continue with their conventional SAAD Dependency intervention, comprising activities that are carried out mainly at the users’ homes and are oriented to support their activities of daily living. This intervention is of personalized attention and its average intensity is about 20min per day from Monday to Sunday.

Intervention group: intensified home care intervention+trainingThe intervention in the experimental group will be received by both users and informal caregivers:

The users will receive an intensification in their SAAD Dependency of a minimum of 1h per day and a maximum of 3.5h (the equivalent to the average state cost of living in a NH in 2019) from Monday to Sunday. The intensification will be personalized according to the specific needs of the user that professionals deem necessary to meet, taking into account the wishes of the person. The weekly distribution of the intervention will be flexible in terms of schedules, as agreed upon by professional and informal caregivers.

Each informal caregiver will receive multimodal online training following the person-centred care model23 with the objective of providing knowledge, skills and attitudes that empower them to face the challenge of caregiving, guaranteeing quality care, preventing situations that may negatively affect both the person and the family dynamics, and enabling an optimal evolution in caregiving. The training will be composed of 9 topics and 23 learning units and will be available on a website.

Assessments and outcomesAssessments will be made by members of the research team with experience in the field of geriatrics and gerontology, trained in research methods, calibrated with each other to minimize bias and blinded to group assignment. A baseline assessment and monthly and quarterly assessments will be performed during 15 months of follow-up. Baseline and quarterly assessments will be face-to-face and monthly through SAAD reports.

Main outcomeThe main outcome will be the time to willingness for NH admission, measured from inclusion in the study to participants’ willingness for admission.

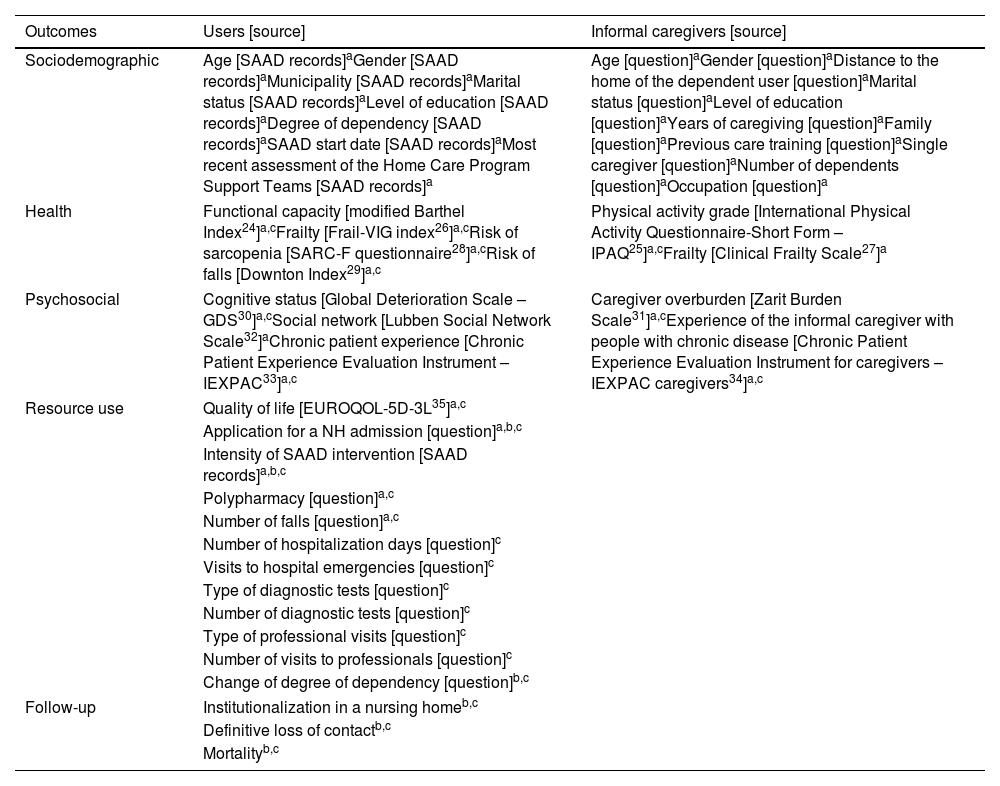

Secondary outcomesSecondary outcomes will be differentiated between sociodemographic, health, psychosocial, resource use and follow-up variables (Table 2).

Secondary outcomes for users and informal caregivers.

| Outcomes | Users [source] | Informal caregivers [source] |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | Age [SAAD records]aGender [SAAD records]aMunicipality [SAAD records]aMarital status [SAAD records]aLevel of education [SAAD records]aDegree of dependency [SAAD records]aSAAD start date [SAAD records]aMost recent assessment of the Home Care Program Support Teams [SAAD records]a | Age [question]aGender [question]aDistance to the home of the dependent user [question]aMarital status [question]aLevel of education [question]aYears of caregiving [question]aFamily [question]aPrevious care training [question]aSingle caregiver [question]aNumber of dependents [question]aOccupation [question]a |

| Health | Functional capacity [modified Barthel Index24]a,cFrailty [Frail-VIG index26]a,cRisk of sarcopenia [SARC-F questionnaire28]a,cRisk of falls [Downton Index29]a,c | Physical activity grade [International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form – IPAQ25]a,cFrailty [Clinical Frailty Scale27]a |

| Psychosocial | Cognitive status [Global Deterioration Scale – GDS30]a,cSocial network [Lubben Social Network Scale32]aChronic patient experience [Chronic Patient Experience Evaluation Instrument – IEXPAC33]a,c | Caregiver overburden [Zarit Burden Scale31]a,cExperience of the informal caregiver with people with chronic disease [Chronic Patient Experience Evaluation Instrument for caregivers – IEXPAC caregivers34]a,c |

| Resource use | Quality of life [EUROQOL-5D-3L35]a,c | |

| Application for a NH admission [question]a,b,c | ||

| Intensity of SAAD intervention [SAAD records]a,b,c | ||

| Polypharmacy [question]a,c | ||

| Number of falls [question]a,c | ||

| Number of hospitalization days [question]c | ||

| Visits to hospital emergencies [question]c | ||

| Type of diagnostic tests [question]c | ||

| Number of diagnostic tests [question]c | ||

| Type of professional visits [question]c | ||

| Number of visits to professionals [question]c | ||

| Change of degree of dependency [question]b,c | ||

| Follow-up | Institutionalization in a nursing homeb,c | |

| Definitive loss of contactb,c | ||

| Mortalityb,c | ||

The research team will be in charge of collecting the pseudo-anonymized data and entering them in coded form in an electronic database (repository) created by the monitoring unit of the Foundation for Health and Ageing of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, an external foundation subcontracted to provide monitoring and evaluation services. A study monitoring and evaluation plan will be developed, in accordance with the project objectives and the protocol, combining internal and external evaluation criteria and actions for the different monitoring stages.

Statistical analysisThe hypothesis of homogeneity of the groups will be tested quantitatively by bivariate statistical tests (chi-square for categorical variables, and Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables), and qualitatively by exploring the overlap between the means and 95% confidence intervals of the variables in the two intervention groups. Possible differences between groups will be assessed in terms of clinically relevant differences using, as far as possible, published values of minimally important differences for each relevant outcome in the study.

The effectiveness of the intervention will be performed by calculating multivariate Cox regression models, with time to institutionalization request as the dependent variable, and multivariate logistic regression models, with institutionalization request as the dependent variable. SPSS will be used for statistical analysis.

DiscussionThe main objective of the study is to evaluate the effect of a multimodal home care interventions in users with a high level of dependency and their informal caregivers. The results derived from this research will increase the knowledge on the subject since, as far as we know, in Mediterranean countries the evidence is scarce.

However, it is known that in northern European countries,19,36 long-term care provision emphasizes enabling the older people to continue living at home, independently, for as long as possible, and statistics show that this is being achieved. Spanish families bear a disproportional weight in the care of dependent people against the original aim of Spanish Dependency Act whose main goal was to offer formal services as a quasi-exclusive type of attention to dependent people.37 For this reason, it is expected that an intensification of the SAAD Dependency will delay or avoid institutionalization of dependent older adults in NHs, while improving their health and psychosocial levels. At the level of informal caregivers, a decrease in their overburden is expected, as well as an improvement in their quality of life due to the intensification of the SAAD Dependency and online training, since coping strategies will become increasingly crucial to improve the quality of the care they provide, to increase and/or reinforce their social network and to stay healthy.38 At the level of resources used, the proposed intervention is expected to be more cost-effective than conventional intervention or admission in NHs; one of the reasons is that the maximum amount of intensive intervention is calculated with the idea of not exceeding the equivalent of the state average cost of living in a NH. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that participants who benefit from the intensive intervention will improve their quality of life and reduce costly health consequences39–41 such as falls, hospitalizations, doctor visits, diagnostic tests or polypharmacy, compared to participants who receive the conventional intervention. At the community level, the transfer of these results to public policies is expected, following the example of Sweden, which, since the 1990s, has implemented aging-in-place policies increasing the share of older adults dependent on home care instead of residing in NHs.36

Regarding the limitations, the present study is innovative in nature, so no scientific literature has been found to support the sample calculation. Given the lack of data, a sample size that is estimated to be sufficient to show the effectiveness of the intervention has been considered, based on speculative hypotheses. These hypotheses and the final power of the study will be subsequently evaluated.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.