Geriatric and gerontology healthcare workers are associated with a series of psychosocial risks such as death, bereavement and illness, and this implies a significant emotional and work overload, which can lead to negative attitudes toward death.

ObjectiveThe aims of this study were to assess attitudes toward death, the level of burnout and the relationship between geriatrics and gerontology professionals.

MethodA correlational, cross-sectional study was conducted, in which the 42 participants in the sample completed an online questionnaire including the Revised Profile of Attitudes to Death (PAM-R) and the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS).

ResultsThe results obtained show that the predominant attitude toward death in the sample is that of neutral acceptance, and with regard to burnout syndrome, moderate average levels are found in the dimensions of emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment, but a low level of depersonalisation.

ConclusionHealthcare workers with attitudes of greater fear of death or acceptance of escape tend to experience higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation, as do those with an attitude of death avoidance, who also have lower personal fulfillment.

El personal sanitario de geriatría y gerontología se relaciona con una serie de riesgos psicosociales como son la muerte, el duelo y la enfermedad, esto implica una sobrecarga emocional y laboral importante, las cuales pueden derivar en actitudes hacia la muerte negativas.

ObjetivosLos objetivos de este estudio fueron evaluar las actitudes hacia la muerte, el nivel de burnout y la relación entre profesionales de geriatría y gerontología.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio correlacional y transversal, en el que los 42 participantes de la muestra cumplimentaron un cuestionario online que incluía el Perfil Revisado de Actitudes hacia la Muerte (PAM-R) y el Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS).

ResultadosLos resultados obtenidos muestran que la actitud hacia la muerte predominante en la muestra es la de aceptación neutral, y en cuanto al síndrome de burnout, se encuentran niveles medios moderados en las dimensiones de agotamiento emocional y realización personal, pero un nivel bajo de despersonalización.

ConclusiónLos trabajadores sanitarios con actitudes de mayor miedo a la muerte o de aceptación de la fuga tienden a experimentar mayores niveles de agotamiento emocional y despersonalización, al igual que los que tienen una actitud de evitación de la muerte, que además presentan una menor realización personal.

In recent years, there has been a shift in the place of death from the home to the hospital environment. Both internationally and nationally, it has been found that the desire to die at home is the majority among the elderly,1 although the reality is that more than half do so in hospitals,2 with health care personnel being responsible for sustaining this experience. This fact becomes even more relevant if attention is focused on the elderly population, in which deaths have been more numerous and to a greater extent, in hospital or residential contexts.3 The total number of deaths in hospitals and social-health centers (around 68–70% of the total) means that health personnel in both types of centers are responsible for dealing with the death of the elderly.

Death has been considered as a biological and psychosocial process, in which a large number of vital acts are extinguished in such a gradual and silent sequence that generally escapes simple observation.4 Death is not strictly a biological event, but a socially and culturally constructed process.5 Attitudes are characterized by presenting, from a structural point of view, an affective component, a cognitive component and a behavioral component.6 Attitudes toward death refer to the feeling that an individual presents toward the general concept of death, both their own and the death of other people7 and which is influenced by personal, religious, cultural, social and philosophical belief systems.8 One of the developments to investigate attitudes toward death was built on the basis of the theory of personal meaning.9

Esnaashari and Kargar9 collect as a model of perception of attitudes toward death, that the result obtained is based on existential beliefs and a multidimensional view of attitudes is adopted. A premise derived from this approach is that a person's inability to find personal meaning in life and death gives rise to fear of death. According to this model, there are 5 attitudes toward death: two of them – fear of death and death avoidance – refer to negative, wary, and avoidant dispositions toward dying. Fear of death involves thoughts and feelings of dread of death and the dying process, while avoidance involves attempts to put thoughts of death out of mind as well as to avoid conversations about death. In contrast, three attitudes toward death – neutral acceptance, approach acceptance, and escape acceptance – represent different ways of accepting the end of life. Neutral acceptance entails perceiving death as a natural part of life and neither welcoming it nor living it in fear. Approaching acceptance involves conceiving death as the gateway to a happy life after death and making it possible to reconnect with deceased loved ones. The acceptance of escape entails perceiving death as the way to free oneself from the pain and suffering that occurs in life. Acceptance of death has been found to reduce people's anxiety toward the idea of death.8 Regarding the main factors that influence attitudes toward death among healthcare workers are the age,10 marital status, years of work experience,11 the frequency with which they face the death of patients in their daily practice or having received previous training on death and the dying process.12,13 Duran and Polat examined how socio-demographic characteristics affecting their attitudes toward death. They found that among younger nurses the attitude of approach acceptance was higher while escape acceptance was higher among singles nurses.14 Another study also found that among nurses who had received some training on death, the predominant attitude was neutral acceptance.10

Healthcare professionals frequently face situations that cause emotional fluctuations and increase stress. Among them, some of the most intense are the contact with fear, illness and death of a patient and with the patient's relatives.15,16 The concept of burnout defines the state of physical and mental exhaustion that appears among professionals.17 Maslach et al. developed the construct to be characterized by three independent domains: emotional exhaustion (EF), defined as the decrease of emotional resources to cope with work, depersonalization (PD) or development of negative attitudes and feelings and cynicism toward the recipients of their work and decreased sense of personal accomplishment or tendency to evaluate one's own work in a negative way, with low professional self-esteem.18 Several studies have been carried out to study the relationship between burnout and attitudes toward death.15,19–22

The present study aims to analyze the attitudes toward death, the prevalence of burnout syndrome and the relationship between both variables in all the members of the medical teams that provide care to the elderly who are going to die.

Objectives and hypotheses

- -

O1: To investigate what are the predominant attitudes toward death among these health care workers.

- -

O2: To quantify the level of burnout among healthcare personnel facing the end of life of the elderly patient.

- -

O3: To explore the possible relationship between attitudes toward death and burnout in healthcare personnel facing the end of life of the elderly patient.

- -

O4: To analyze the relationship between attitudes toward death with age and work experience, as well as the level of burnout with the latter two.

Based on prior literature and the set objectives, we expect to find a positive and statistically significant correlation between the fear of death attitude and the dimensions of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Conversely, a negative correlation is anticipated with the personal realization dimension. Similarly, the avoidance of death attitude is expected to show correlation patterns comparable to these dimensions. In contrast, the escape acceptance attitude is anticipated to correlate positively with the dimensions of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization but negatively with personal realization. Additionally, we suggest that the neutral acceptance of death attitude associates positively with personal realization and negatively with depersonalization. Regarding professional differences, we predict that there will be statistically significant differences in attitudes toward death between nurses and other health professionals, such as auxiliary nursing care technicians, doctors, and psychologists. Finally, it is proposed that there may be differences in the dimensions of burnout syndrome between nurses and the rest of the health professionals.

MethodParticipantsThe total number of professionals who responded to the questionnaire was 44; however, 2 of them stated that they were unable to complete it, so the total sample was 42 participants. In terms of sex, 78.6% were women and 21.4% were men. The mean age of the sample was (M=39.62, SD=11.57). Regarding nationality, 100% of the sample was of Spanish nationality. The participants with a university master's degree were in the majority (57.2%), followed by those with a bachelor's degree (28.6%) and, finally, participants whose level of education was either vocational training or a doctorate (7.1%, respectively). Only health care workers who expressed their willingness to participate voluntarily in the study and who met the following inclusion criteria were selected: (a) Health care professionals (nurses, nursing assistants, nursing care technicians) from both residential care centers for the elderly and hospitals. In the case of the latter, they should work in medical units in which they frequently attend elderly patients who are about to die (oncology, palliative care, intensive care and geriatrics). (b) They should be active workers and exercise their profession in Spain. (c) They should agree to participate in the study by accepting the informed consent form and completing the research questionnaire in full. Other social and health care professionals who, although they work with elderly people, are not directly involved in end-of-life care (such as occupational therapists or social workers) were excluded. As well as people in training or already retired.

Instruments- -

A questionnaire of sociosdemographic and professional variables (prepared ad hoc for the research). Age, sex, nationality, education, profession and years of work experience were evaluated.

- -

Revised Profile of Attitudes toward Death (PAM-R) by Wong et al.,23 in the version translated into Spanish.24 It is a revision of the PAM (Profile of Attitudes toward Death). Composed of 32 items reflecting 5 dimensions/attitudes: (a) fear of death, (b) avoidance of death, (c) approach acceptance, (d) neutral acceptance and (e) escape acceptance. All items have a 7-point Likert scale response format that covers options from “Totally in disagree” (1) to “Totally agree”.7 For each dimension, the average score of the scale is obtained by dividing the total score obtained in each one by the number of items that comprise it. In 2007, this scale was validated for the Spanish population by Schmith, obtaining good results in terms of reliability (Cronbach's α) of .83, .90, .93, .69 and .81 respectively, for each one of the five dimensions.25

- -

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) by Maslach and Jackson (1981), specifically the MBI Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) version, in its adaptation to the Spanish population.26 It consists of 22 items that score on a Likert-type scale, (1=never and 7=every day). It measures the three constituent dimensions of burnout syndrome through 3 subscales: (a) emotional exhaustion subscale, (b) depersonalization subscale and (c) personal accomplishment subscale. The MBI Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) questionnaire was validated by Gil-Monte, obtaining the following Cronbach's α coefficients for each of the three subscales: emotional exhaustion (.85), depersonalization (.58) and achievement staff (.71).27

To facilitate the telematic distribution of the instruments used, the Google Forms platform was used. The link was published and disseminated through various social networks. Likewise, contact was made via e-mail with the management of different residences for the elderly in various autonomous communities or institutions such as the Spanish Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology (SEGG).

The link to the Google Forms questionnaire was sent and/or published with a brief presentation of the study, the informed consent stating the objectives of the study, the purpose of the data collection, as well as, the way in which the data would be processed, in accordance with the Organic Law 3/2018 on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights. The target population was also informed and participants were asked to disseminate it among their networks of contacts. A non-probabilistic snowball sampling was carried out, and two e-mail addresses were provided to which participants could contact in order to resolve any doubts that arose both before and during the completion of the survey. The entire sample agreed to participate in the study by giving their consent to collaborate in this research project. In order to process the data, a database was first created using the Microsoft Excel program, from which it was transferred to the IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0.1.1 statistical package. All the analyses mentioned below were calculated, both descriptive and inferential, assuming a significance level α of 0.05 (95% confidence level).

Statistical analysisA quantitative, correlational, cross-sectional design was used to carry out this research. Sampling was non-probabilistic, purposive using the snowball system, contacting health centers by email and asking participants to inform colleagues.

First, descriptive statistics were obtained for the 5 subscales of the Revised Profile of Attitudes Toward Death (PAM-R), as well as for the 3 subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS). Taking as a reference the cut-off points provided by the MBI-HSS questionnaire to assess the level of the participants (low, medium or high) in each of its three dimensions, the number of professionals who were at each level was quantified by means of percentages. Subsequently, the Shapiro–Wilk normality test was calculated, since the total sample was composed of 42 participants (n<50), for the 5 subscales of the Revised Profile of Attitudes Toward Death (PAM-R) and the three dimensions of the Burnout Syndrome of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS). After failing to ascertain the normal distribution of the data for any of the variables (p<0.05), it was decided to choose nonparametric tests to perform the rest of the analyses. For the analysis of correlations between the 5 subscales of the PAM-R (fear of death, death avoidance, neutral acceptance, approach acceptance, and escape acceptance) and the 3 subscales of the MBI-HSS (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal fulfillment), the nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficient test was used. Finally, to study the possible statistically significant differences between the group of nurses and the other health professionals (auxiliary nursing care technicians, physicians and psychologists grouped into a single category), both in the 5 subscales of the PAM-R and in the 3 subscales of the MBI-HSS, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used.

ResultsFor the 5 dimensions/subscales of the PAM-R, the attitude with the highest mean score among the total sample is the neutral acceptance attitude (M=5.63, SD=1.58), followed by the Escape acceptance attitude (M=3.14, SD=1.74). In contrast, the sample presents the lowest mean in death avoidance (M=2.53, SD=1.86). With regard to burnout syndrome, in this study the total sample presents a mean score of 21.55 (SD=11.81) in the emotional exhaustion subscale, which allows placing the mean level at moderate. Similarly, in the personal accomplishment subscale, the mean score is 36.43 (SD=9.37), which indicates a moderate level at the sample level. However, in the depersonalization subscale, the mean value is 4.48 (SD=5.11) so that the overall average level is low. Analyzing the scores of the subscales of the MBI-HSS at the individual level, 38.1% of the health professionals were at a high level of emotional exhaustion, 9.5% of the sample at a high level of depersonalization and 26.2% at low levels of personal accomplishment.

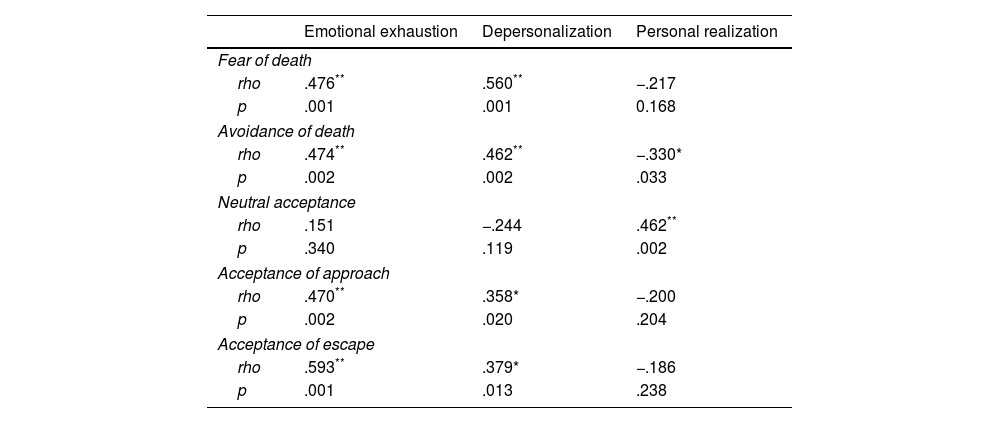

The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was calculated, since the total sample consisted of 42 participants (n<50), for the 5 subscales of the Revised Profile of Attitudes Toward Death (PAM-R), the three dimensions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Burnout Syndrome and the variable age. The Shapiro–Wilk normality test (n<50) was calculated for each of the variables under study. Regarding the association between the 5 dimensions/attitudes toward death of the PAM-R and the 3 subscales of the MBI-HSS. Table 1 shows the results of the application of the nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficient test.

Spearman correlation coefficient between the 5 dimensions/attitudes toward death according to the PAM-R and the 3 dimensions of Burnout Syndrome according to the MBI-HSS.

| Emotional exhaustion | Depersonalization | Personal realization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of death | |||

| rho | .476** | .560** | −.217 |

| p | .001 | .001 | 0.168 |

| Avoidance of death | |||

| rho | .474** | .462** | −.330* |

| p | .002 | .002 | .033 |

| Neutral acceptance | |||

| rho | .151 | −.244 | .462** |

| p | .340 | .119 | .002 |

| Acceptance of approach | |||

| rho | .470** | .358* | −.200 |

| p | .002 | .020 | .204 |

| Acceptance of escape | |||

| rho | .593** | .379* | −.186 |

| p | .001 | .013 | .238 |

Note. rho, Spearman correlation coefficient value; p, bilateral significance level.

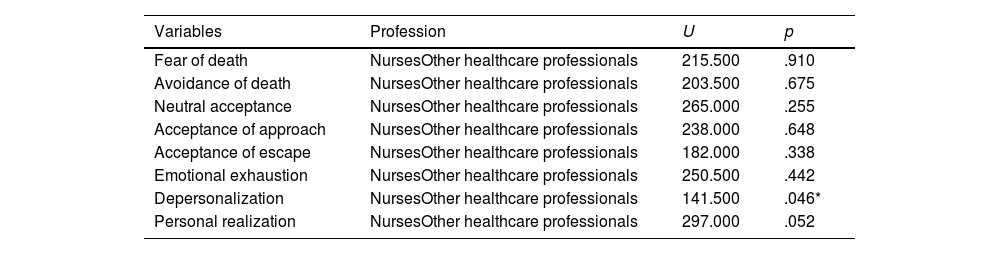

The fear of death attitude was positively and statistically significantly correlated with the variable emotional exhaustion (rho=0.436, p=0.001) and depersonalization (rho=0.560, p<0.001). Death Avoidance attitude was positively and significantly correlated with the variable emotional exhaustion (rho=0.474, p=0.002) and depersonalization (rho=0.462, p=0.002) but negatively with the variable personal accomplishment (rho=−0.330, p=0.33). The neutral acceptance attitude was positively and significantly correlated with the personal accomplishment variable (rho=0.462, p=0.002) while the approach acceptance attitude was with the emotional exhaustion subscale (rho=0.470, p=0.002) and depersonalization (rho=0.358, p=0.020). Finally, the attitude escape acceptance also correlated positively and statistically significantly with the variable emotional exhaustion (rho=0.593, p<0.001) and depersonalization (rho=0.379, p=0.013). To examine the possible differences in all the variables under study between the group of nurses and the group formed by the rest of the healthcare professionals, the Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples was used, obtaining no statistically significant differences in any of them, except in the depersonalization dimension (U=141.500, p=.046) (Table 2).

Results of group comparison using the Mann–Whitney U statistic for all variables under study.

| Variables | Profession | U | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of death | NursesOther healthcare professionals | 215.500 | .910 |

| Avoidance of death | NursesOther healthcare professionals | 203.500 | .675 |

| Neutral acceptance | NursesOther healthcare professionals | 265.000 | .255 |

| Acceptance of approach | NursesOther healthcare professionals | 238.000 | .648 |

| Acceptance of escape | NursesOther healthcare professionals | 182.000 | .338 |

| Emotional exhaustion | NursesOther healthcare professionals | 250.500 | .442 |

| Depersonalization | NursesOther healthcare professionals | 141.500 | .046* |

| Personal realization | NursesOther healthcare professionals | 297.000 | .052 |

Note. U, value of the Mann–Whitney U statistic; p, bilateral significance level.

The study aimed to explore attitudes toward death and the prevalence of Burnout Syndrome among healthcare professionals who assist older adults at the end of their lives. The study found that Neutral Acceptance was the predominant attitude toward death among the healthcare personnel, indicating that death is accepted as a natural part of life without fear or expectation. The attitude of Avoidance of death was less prevalent among the healthcare workers, indicating that they are less likely to avoid thinking or talking about death. Results of studies such as that of Malliarou et al., show that those professionals who were more frequently in contact with patients at the end of life, presented higher levels of acceptance and lower levels of fear of death.21 The target population of this study (and therefore, the sample of the same), faces a large number of deaths per year (increasing even more in the last two years) and could therefore be one of the explanatory factors of the results obtained.

With respect to the objective of quantifying the level of burnout among health care professionals who provide care to the elderly who are dying, moderate average levels were obtained in both the Emotional Exhaustion and Personal Accomplishment dimensions, as well as a low level of depersonalization. These results partially coincide with those of the research carried out by Llor-Lozano et al. in emergency and critical care professionals, since they also obtained a moderate average score for emotional exhaustion and low for depersonalization, but in the personal accomplishment dimension the average level was high (and not moderate as in the present work).28

The study found a positive and statistically significant correlation between attitudes of fear of death and acceptance of escape with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, but not with personal accomplishment. Therefore, only hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 3 can be partially confirmed. However, these results are in line with those obtained by Gama et al. or Malliarou et al.15,21 It could be deduced that among those professionals who have to face the death of their patients from the fear of the dying process or live it as an escape route to an existence of suffering, it is more likely that in the exercise of their profession, in which they come into continuous contact with death, there is a greater depletion in the emotional resources allocated to their work, or to develop negative attitudes toward patients who are going to die. For hypothesis 2 the avoidance of death attitude correlates positively and statistically significantly with the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization dimensions but negatively with the personal accomplishment dimension, the results obtained in the present study allow confirming it. In this sense, they would agree with those shown by Guo and Zheng or Zheng et al.,20,22 both studies recently conducted in China and with nurses in the specialty of Oncology. For the neutral acceptance attitude, a positive and significant correlation was obtained with the personal accomplishment dimension but not a negative correlation with the depersonalization subscale, so only hypothesis 4, stated based on the findings of Guo and Zheng,20 can be partially confirmed. With this result, perhaps it could be inferred that those healthcare professionals who experience death as a natural life event can carry out their work (often linked to situations of exposure to the dying process) without undermining their sense of competence and professional self-esteem. The study obtained data that did not coincide with previous research, such as the positive correlation of Approach acceptance with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. The study also investigated differences between nursing professionals and other healthcare professionals in attitudes toward death and burnout dimensions, but no significant differences were found except in the depersonalization dimension.

The present study has a series of limitations that deserve attention. First, the number of participants was small, which limits the generalization of these results. Also, the recruitment of the sample by non-probability sampling (snowball sampling) reduces the probability of representativeness of the sample and also makes it difficult to generalize the data. Our goal specifically focuses on those who work with elderly individuals, a relevant subpopulation. Accessing these professionals is challenging due to their limited availability and time constraints resulting from their direct patient care responsibilities. Additionally, the sensitive nature of the topic, attitudes toward death, can create hesitancy and difficulties in obtaining responses. Although there are more women than men in the health professions, the disparity in the number of participants of each sex in the sample is notable and made it difficult to carry out comparative analyses according to this variable. It would be advisable to replicate the study in the future with a larger sample, with a more equal proportion both between men and women and between the different professional categories involved. This could be achieved by improving the dissemination and accessibility of the instrument questionnaire and assessing whether to maintain or reduce its length. In-depth investigation of attitudes toward death and the level of burnout among health care professionals could constitute the starting point for future lines of research. Thus, the knowledge obtained in this study could serve as a basis for the design and implementation of intervention programs aimed at these professionals, which address, from both a psychoeducational and practical approach, aspects such as: training content on death and patient care at the end of life (since research has shown that this is a contributing factor to the improvement of attitudes), communication skills, decision making, increased personal resources for the management of emotionally demanding or stressful situations, attention to the patient's relatives or the management of grief itself.

The study found that most health professionals who assist elderly people at the end of their lives have a neutral attitude toward death, with a minority displaying an attitude of death avoidance. The participants in the study also displayed moderate levels of emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment in relation to burnout syndrome, but a low level of depersonalization. However, a high percentage of health professionals reported experiencing high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and a low perception of personal fulfillment in their work. The study also found that health workers who have a greater degree of fear of death or acceptance of death as an escape route tend to experience higher levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.29,30 On the other hand, those who experience death from an attitude of avoidance are more likely to suffer both emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, but less likely to feel fulfilled and competent in their work. The study also found that the attitude of neutral acceptance correlates with the personal accomplishment experienced while the attitude of approach acceptance does so with the levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, respectively. Finally, the study could not conclude whether there were significant differences in attitudes toward death and burnout between nurses and other health professionals, except for the depersonalization variable.

FinancingThe authors declare that they have not obtained funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank the health professionals for their selfless collaboration that has allowed us to achieve the results of this research.