To describe the application of the WALANT (Wide-Awake Local Anesthesia No Tourniquet) technique in hallux valgus surgery, highlighting its advantages in terms of patient comfort and surgical safety.

MethodsA descriptive study detailing the steps for administering WALANT anesthesia during hallux valgus correction. Patient selection, local anesthetic preparation, injection technique, and surgical approach were documented. The case of a 65-year-old woman with severe hallux valgus undergoing surgery with the WALANT technique is presented.

ResultsThe patient tolerated the procedure well without requiring sedation or experiencing significant pain. Despite the absence of a tourniquet, the surgery was performed with adequate visibility and hemostatic control. Early mobilization was achieved, and the patient reported a high level of satisfaction. At the 2-week follow-up, wound healing progressed favorably and alignment was satisfactory, with no complications observed.

ConclusionWALANT appears to be a safe and effective alternative for hallux valgus surgery, minimizing the risks associated with general or regional anesthesia while improving the overall patient experience. This report outlines the anesthetic protocol routinely used in our practice, which may serve as a foundation for standardizing its application in forefoot procedures. Further comparative and prospective studies are warranted to assess its clinical and functional outcomes over the medium and long term.

Level of clinical evidenceThis is a level 4 evidence study as it focuses on the description of a surgical technique based on clinical experience.

Describir la aplicación de la técnica WALANT (Wide-Awake Local Anesthesia No Tourniquet) en la cirugía de Hallux Valgus, destacando sus ventajas en términos de confort del paciente y seguridad quirúrgica.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo que detalla los pasos para la administración de la anestesia WALANT durante la corrección del Hallux Valgus. Se documentaron los criterios de selección de pacientes, la preparación del anestésico local, la técnica de infiltración y el abordaje quirúrgico. Se presenta el caso de una mujer de 65 años con Hallux Valgus severo intervenida mediante esta técnica.

ResultadosLa paciente toleró correctamente el procedimiento sin necesidad de sedación ni dolor significativo. A pesar de la ausencia de torniquete, se pudo realizar la cirugía con adecuada visibilidad y control hemostático. Se logró una movilización precoz y la paciente refirió un alto grado de satisfacción. En el seguimiento a las dos semanas, la herida mostró una evolución favorable y la alineación fue satisfactoria, sin observarse complicaciones.

ConclusiónLa técnica WALANT se presenta como una alternativa segura y eficaz en la cirugía de Hallux Valgus, al evitar los riesgos asociados a la anestesia general o regional y mejorar la experiencia del paciente. En este estudio se describe detalladamente el protocolo anestésico que utilizamos de forma habitual, lo cual puede contribuir a estandarizar su aplicación en este tipo de procedimientos. No obstante, son necesarios estudios comparativos y prospectivos que analicen su impacto en los resultados clínicos y funcionales a medio y largo plazo.

Nivel de evidencia clínicaEste estudio corresponde a un nivel de evidencia 4, al tratarse de la descripción de una técnica quirúrgica basada en experiencia clínica.

Hallux valgus (HV), commonly referred to as a bunion, is a deformity of the first metatarsophalangeal joint characterized by the lateral deviation of the great toe and the medial deviation of the first metatarsal. This condition often results in significant pain, discomfort, and impaired function, leading many patients to seek surgical correction.1

The choice of anesthesia for HV surgery is crucial as it impacts both the surgical outcome and the patient's overall experience.2 Various anesthetic techniques have been employed for HV surgery, including general anesthesia, regional anesthesia (spinal or epidural), popliteal block, and ankle block. Each of these techniques has its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Currently, the most commonly used anesthetic technique for forefoot surgery is the popliteal sciatic nerve block or ankle block.

Peripheral nerve blocks3Peripheral nerve blocks, such as the ankle block or popliteal sciatic nerve block, are commonly used in forefoot surgery. This technique involves injecting local anesthetic around specific nerves to provide targeted pain relief. They are often combined with sedation to improve patient comfort. While nerve blocks can offer excellent analgesia, they may result in temporary motor block and require precise anatomical knowledge to avoid complications such as nerve injury or local anesthetic toxicity. The use of a tourniquet can be performed with no pain.

Ankle block is also used in forefoot surgery.4 This technique involves injecting local anesthetic into the nerves around the ankle. No motor involvement is affected in this technique, which targets distal nerves. Most patients experience pain if a tourniquet is used.

Wide-Awake Local Anesthesia No Tourniquet (WALANT)The WALANT technique is a newer approach that has gained popularity in hand surgery and is now being explored for use in foot and ankle surgery. WALANT involves the administration of local anesthetic combined with epinephrine directly into the surgical site.5,6 The addition of epinephrine causes vasoconstriction, which minimizes bleeding and provides a clear surgical field without the need for a tourniquet.7

This technique offers several advantages, including the elimination of risks associated with general and regional anesthesia, reduced need for postoperative pain medication, and the ability for patients to provide real-time feedback during the procedure.8 Additionally, the time needed for the procedure is less than that for popliteal or ankle block. The experience in hand and wrist surgery is excellent, as several articles have described positive results in various conditions and types of surgery.5,6,9 Consistent with this, other studies have been conducted on the use of WALANT anesthesia in foot and ankle surgery with good results.10–17 We applied our initial experience with WALANT in hand surgery to foot surgery.

In this article, we describe the use of WALANT in hallux valgus surgery. The aim of our study is to provide a detailed explanation of the technique for administering local anesthesia, as well as to emphasize its advantages in terms of patient comfort, safety, and surgical outcomes. This represents the initial phase of an ongoing project. We have already launched the second phase, which consists of a comparative cohort study evaluating WALANT and sedation versus regional nerve block, with a special focus on patient satisfaction.

Materials and methodsPatient selection and preparationPatients selected for WALANT in HV surgery included those who were otherwise healthy but apprehensive about general anesthesia, as well as elderly patients with medical comorbidities. Preoperative evaluation ensured that patients had no allergies to lidocaine or epinephrine and no significant vascular insufficiency.

Local anesthesia preparationThe components used included lidocaine 2% (20mg/mL, B. Braun), epinephrine 1mg/mL (B. Braun), sodium bicarbonate 840mg/10mL (Grifols), and 0.9% normal saline (Grifols). The hospital pharmacy prepared prefilled syringes containing 4mL of 2% lidocaine, 0.1mL of epinephrine, and 10mL of normal saline. This base mixture was further diluted with additional saline and bicarbonate to reach a final volume of 20mL, resulting in a concentration of 1% lidocaine, 1:200,000 epinephrine, and a bicarbonate ratio of 10:1. All components were mixed in a single syringe immediately before administration. According to protocol, the injection was performed 30min before surgery, using a single bolus with a fan-shaped subcutaneous technique from distal to proximal around the surgical field.

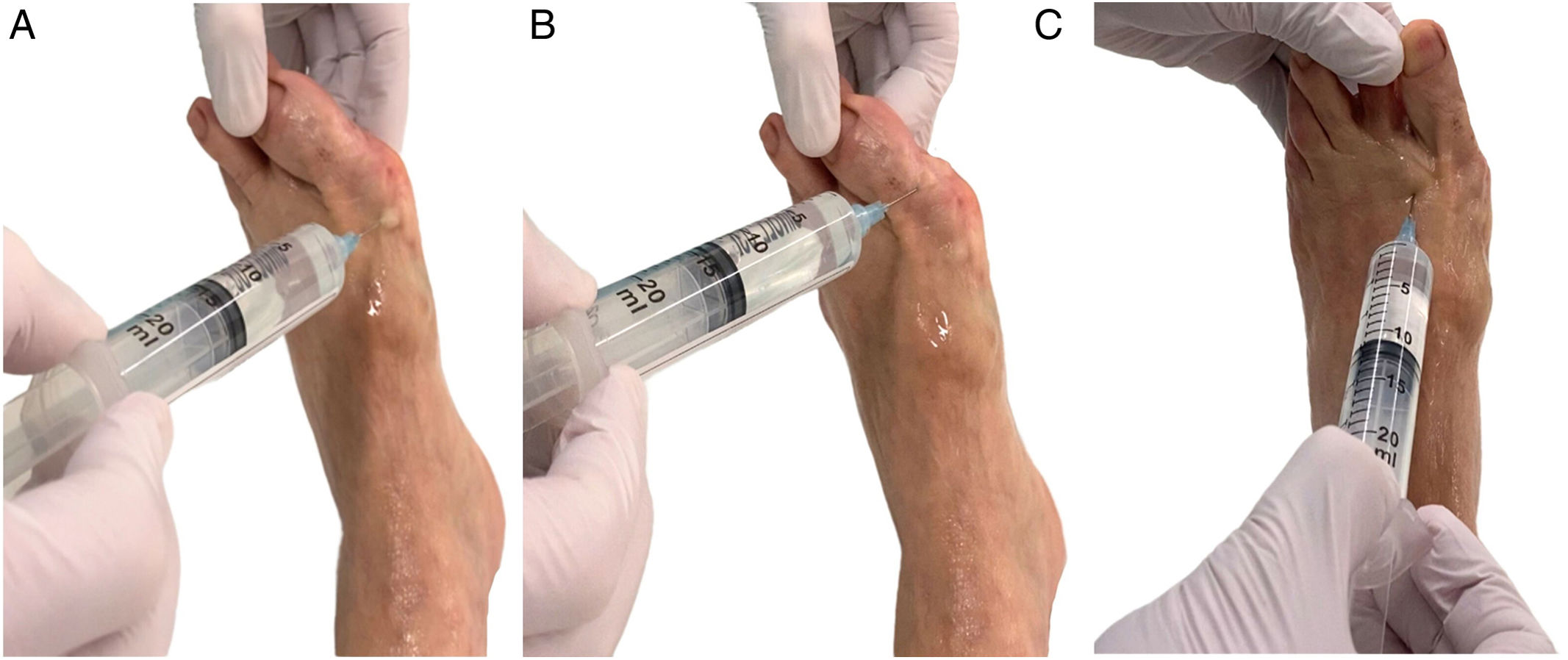

Injection techniqueThe first infiltration was performed in the medial area of the first ray at the mid-diaphyseal level. Initially, the infiltration was performed in the subcutaneous tissue, advancing to the periosteum area of the first metatarsal (Fig. 1). When the periosteum of the bone was touched, the needle was directed dorsally, reaching the first intermetatarsal space (Fig. 2). Approximately 5mL of the anesthetic solution was injected.

Subsequently, we performed the same type of infiltration in the plantar area of the first metatarsal, injecting 5mL of solution (Fig. 3). Once this first infiltration was completed, a medial and lateral periarticular infiltration (Fig. 4) of the metatarsophalangeal joint of the first ray was performed, with approximately 5–6mL infiltrated. Finally, an infiltration was performed through the medial part in the first phalanx (Fig. 4).

During this phase, the most important aspect is the timing of the injection prior to the surgery. At least 30min preoperative time is necessary. Therefore, we administer the anesthesia to the patient while the previous patient is in the operating room.

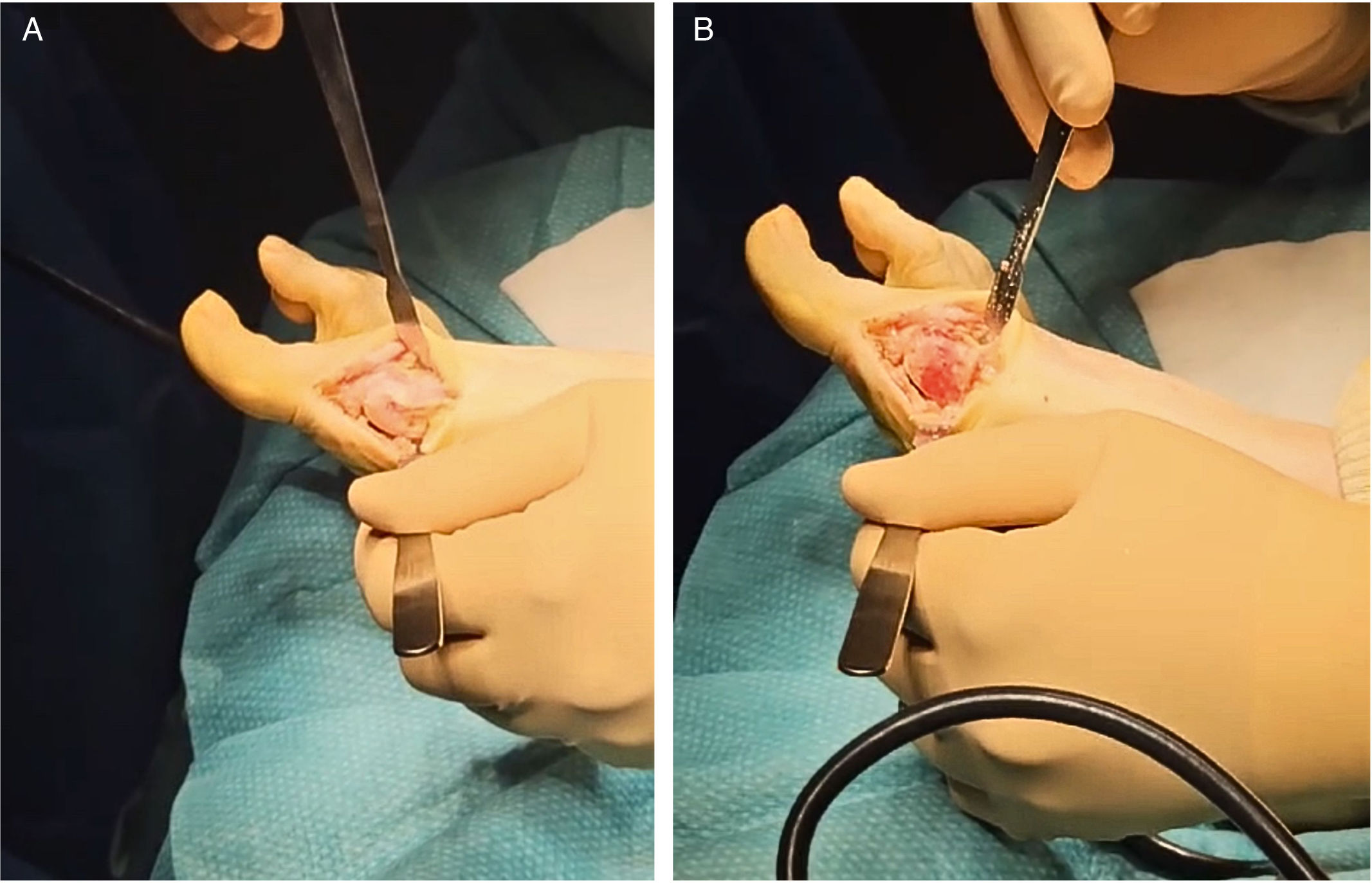

Surgical procedureAfter ensuring adequate anesthesia, a medial longitudinal incision was made in the first ray. Standard surgical steps for hallux valgus correction, including osteotomy, bone realignment, and fixation, were performed. No tourniquet was needed during forefoot surgery; the adrenaline in the anesthetic solution provided chemical ischemia. Cauterization was used in case of bleeding. All procedures were performed in an ambulatory surgery operating room (major outpatient surgery unit), following institutional protocols. Although WALANT allows the procedure to be theoretically feasible in a minor procedure room, we recommend using a fully equipped ambulatory surgery theater to ensure optimal safety and sterility.

Light sedationWe have noticed that many patients find the WALANT anesthetic procedure to be effective. However, some patients with high levels of anxiety or fear may become more agitated upon hearing motorized instruments during surgery. In such cases, a light sedation protocol can be considered. When used, sedation is administered by the anesthesiology team in the preoperative area, typically consisting of a single dose of intravenous midazolam (1–2mg), titrated according to patient weight and tolerance. It is essential to avoid excessive sedation, as patient cooperation and preserved protective reflexes are key components of the WALANT technique.

Postoperative managementPatients were observed for 2h post-surgery for any adverse effects from the anesthesia or bleeding. Vital signs and numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) were monitored every 30min. Postoperative care included oral analgesics, limb elevation, and encouragement of early mobilization exercises to prevent stiffness and weightbearing.

Patients were observed for 2h post-surgery for any adverse effects from the anesthesia or bleeding. Vital signs and numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) were monitored every 30min. Postoperative care included limb elevation, oral analgesia, and early mobilization exercises to prevent stiffness and promote functional recovery. The standard analgesic regimen consisted of alternating paracetamol 1g every 8h with either dexketoprofen 25mg every 8h or metamizole 575mg every 8h, administered for the first 5 days. Rescue analgesia was prescribed with tramadol 50mg every 24h, with the possibility of increasing to every 12 or 8h based on patient needs. Oral ondansetron was also provided as rescue medication for nausea or vomiting. After the initial 5-day period, analgesic doses were gradually tapered. Additionally, prophylactic subcutaneous enoxaparin was prescribed once daily for 10 days to reduce the risk of thromboembolic events.

Results: case illustrationA 65-year-old woman with a severe HV deformity underwent correction using the WALANT technique. The distal rotational metatarsal osteotomy (DROMO) technique was used to correct the firth ray deformity (Fig. 5). She reported no pain during the procedure and was able to walk with minimal discomfort immediately post-surgery. Follow-up at 2 weeks showed satisfactory wound healing and alignment correction, with no complications noted.

DiscussionThe use of the WALANT technique has revolutionized surgical approaches in multiple specialties, especially in hand and wrist surgery, due to its numerous advantages over traditional regional and general anesthesia techniques.5,6,9 However, its application in foot and ankle surgery is still recent, with increasing evidence supporting its safety and effectiveness.10–17

In this case, hallux valgus deformity correction using WALANT provided satisfactory results both in surgical terms and in the patient's experience. The absence of a tourniquet eliminated discomfort associated with prolonged ischemia, significantly improving patient comfort during the procedure.18 Additionally, the use of adrenaline in the local infiltration ensured a bloodless surgical field, facilitating precise surgical maneuvers and reducing the need for intraoperative hemostasis.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the WALANT technique is a safe and effective alternative for less complex foot and ankle surgeries, with results comparable to traditional regional anesthesia techniques.11,12,16 Tucker et al. (2018) and Fischer and Rhee (2019) reported similar experiences in forefoot surgery, highlighting shorter overall surgical time and earlier patient recovery as key advantages.12,15 In line with these studies, our case reinforces these conclusions, showing early recovery and no significant postoperative complications.

Clinical advantages and relevance- -

Patient comfort: the WALANT approach eliminates the discomfort associated with tourniquet use. Patients only experience the initial needle prick, with no subsequent pain during the procedure. Additionally, the lack of tourniquet use eliminates many complications associated with ischemia.18

- -

Medical suitability: the WALANT technique is particularly beneficial for patients with medical comorbidities who are at a higher risk for complications under general anesthesia. This method allows for safer surgical intervention without the requirement for extensive preoperative optimization.

- -

Surgical field visibility: the vasoconstrictive properties of epinephrine create a bloodless field, enabling precise surgical maneuvers. By avoiding the use of a tourniquet, issues associated with post-tourniquet release bleeding and swelling are minimized. This makes wound closure easier and reduces postoperative complications.

- -

Patient participation during surgery: the WALANT technique allows for active patient participation during surgery when necessary. This enables real-time assessment of outcomes and allows for intraoperative adjustments to optimize results.

- -

Prolonged local analgesia: the combination of lidocaine with epinephrine delays systemic absorption and extends the duration of local anesthesia, often providing several hours of effective postoperative pain control. According to the available literature, the onset of anesthesia is rapid (<2min), and the presence of epinephrine at a 1:100,000 concentration significantly prolongs the analgesic effect, with clinical efficacy lasting approximately 3–6h, and in distal forefoot soft tissues potentially up to 10h. This prolonged action reduces the need for systemic opioids and facilitates early discharge.19,20

This study is focused on describing the WALANT technique applied to hallux valgus correction, based on our experience since 2020. Its aim is not to analyze outcomes but to provide a detailed, reproducible surgical protocol. Therefore, the inclusion of a single illustrative case is intentional, and not a limitation in sample size. This publication represents the first phase of a broader research project. The second phase, currently underway, is a prospective cohort study comparing WALANT with sedation versus regional nerve block, aiming to evaluate efficacy, safety, functional outcomes, and patient satisfaction in a larger population.

Regarding safety, especially the use of epinephrine in distal extremities such as the foot, we acknowledge that historical concerns about ischemia or necrosis have limited its adoption among some surgeons. Recent literature and extensive clinical experience support the safe use of epinephrine at low concentrations (1:100,000–1:200,000) in distal foot soft tissues. Large series and retrospective studies in podiatric populations have shown no vascular complications even in digital forefoot blocks using epinephrine at these dilutions.21 Specific evaluations in digital nerve blockade confirm safety in healthy patients at 1:100,000–1:200,000 concentrations, with no observed ischemic events.22 Systematic reviews also support such practice for toe and finger procedures, highlighting a significantly prolonged anesthetic effect and reduced bleeding without serious adverse effects, though caution is advised in cases of compromised peripheral circulation.23 In our protocol, the final concentration used is approximately 1:200,000, far below known toxic thresholds, and no vascular complications have been observed. Furthermore, we routinely wait 20–25min after injection before incision to ensure maximal vasoconstriction and surgical field optimization.

We recognize that broader clinical acceptance of WALANT in foot surgery will require more extensive data, and our ongoing study is designed to address this.

Ethical approval and patient consentThe study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case and accompanying images.

ConclusionIn conclusion, we found that the WALANT technique for HV surgery offers numerous benefits, including enhanced patient comfort, suitability for high-risk patients, and excellent surgical field visibility. This study focuses on describing the technique for performing WALANT anesthesia in hallux valgus surgery, providing a practical guide for its application. Our findings highlight the feasibility and advantages of this approach. The results of this investigation could serve as a foundation for future prospective cohort studies or randomized controlled trials aimed at further evaluating the clinical outcomes and long-term benefits of this technique.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Financial disclosureNone reported.

Conflict of interestNone reported.