Periprosthetic knee infections are serious complications after knee arthroplasty, affecting 1–2% of patients with primary surgery and up to 20% of revisions. The DAIR strategy (debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention) has emerged as a treatment for acute infections, allowing component retention in certain cases, with a high success rate.

ObjectivesThis review discusses its application, success factors, techniques such as the “double DAIR” and postoperative management, highlighting the importance of correct patient selection and the combination of a thorough and meticulous surgical technique with appropriate antibiotic therapy to optimise results.

MethodsAn exhaustive updated literature search was conducted regarding the use of DAIR in acute periprosthetic infections, highlighting the step-by-step procedure and some surgical tips that are helpful when performing it. Based on this, recommendations were made for physicians interested in the subject.

ResultsA series of recommendations are made based on current literature, which are a useful guide when dealing with patients with acute infections in the context of knee prostheses, with a success rate greater than 70% in most cases where the patient is well selected.

ConclusionsDAIR is a useful and effective tool in the eradication and treatment of acute periprosthetic infections, with a good success rate. It is a cheap, technically simple and reproducible procedure, so as a group, we suggest it be adopted globally by orthopaedic surgeons.

Las infecciones periprotésicas de rodilla son complicaciones graves postartroplastia de rodilla que afectan entre el 1 y el 2% de pacientes con cirugía primaria y hasta el 20% de las revisiones. La estrategia DAIR (desbridamiento, antibióticos y retención de implantes, por sus siglas en inglés) surge como tratamiento para infecciones agudas, permitiendo en ciertos casos retener los componentes, con una alta tasa de éxito.

ObjetivosEsta revisión discute su aplicación, los factores de éxito, las técnicas como el «doble DAIR» y el manejo postoperatorio, subrayando la importancia en la correcta selección de pacientes y la combinación con una técnica quirúrgica prolija y meticulosa con terapia antibiótica adecuada para la optimización de resultados.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda exhaustiva actualizada de la literatura en relación con el uso del DAIR en infecciones agudas periprotésicas, destacando el paso a paso del procedimiento, así como algunos consejos quirúrgicos que son de ayuda en el momento de realizarlo. Con base en esto, se realizaron recomendaciones para médicos interesados en el tema.

ResultadosSe realiza una serie de recomendaciones basada en la literatura actual, las cuales son una guía útil en el momento de enfrentarnos a pacientes con infecciones agudas en el contexto de prótesis de rodilla, con una tasa de éxito mayor al 70% en la mayoría de los casos donde el paciente es bien seleccionado.

ConclusionesEl DAIR es una herramienta útil y eficaz en la erradicación y el tratamiento de infecciones periprotésicas agudas, con una buena tasa de éxito. Es un procedimiento barato, técnicamente sencillo y reproducible, por lo que, como grupo, recomendamos sea adoptado de manera global por cirujanos ortopédicos.

Periprosthetic knee infections (PPIs) are one of the most complex and challenging complications after knee arthroplasty, affecting between 1% and 2% of primary arthroplasties and up to 20% of revision arthroplasties.

The definition of acute PPI currently lacks universal consensus and varies significantly in the literature, ranging from infections occurring within the first four weeks after surgery1 to those occurring within twelve weeks after surgery.2 Acute haematogenous PPIs are characterised by the onset of symptoms within a period of less than 4–6 weeks but occurring more than 3 months after the index surgery.2

Despite advances in surgical technique and postoperative care, the incidence of acute PPIs in knee prostheses remains a significant concern, representing the leading cause of early revision. The high number of total knee arthroplasties performed annually worldwide, along with the progressive ageing of the global population, make prosthetic joint infections highly costly for healthcare systems. They are associated with increased implant failure, multiple revision surgeries, loosening, and up to three times higher mortality.3 Early and effective management of these infections is essential to achieve favourable results and ensure implant survival, thus improving patients’ quality of life and reducing associated costs, which have been reported to reach up to USD $60,000 per case.3

Although two-stage replacement is recognised as the gold standard for the treatment of PPIs,4 in the case of acute infections, the literature has shown favourable results with aggressive surgical cleaning, achieving preservation of prosthetic components, such as debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR), as well as single-stage revision.

DAIR emphasizes the importance of performing aggressive surgical debridement combined with appropriate antibiotic therapy, replacement of mobile prosthetic components, and maintaining femoral, tibial, and patellar implants in place in a single surgery. In recent years, the “double DAIR” technique has also been described. This technique involves a second surgical cleaning after a period of 5–7 days, which can be performed with or without a new insert replacement and could improve the success rates of this procedure.5

Single-stage revision also takes a more radical approach, replacing the entire infected prosthesis in a single surgical procedure. Each procedure has its own merits and limitations, reflecting the constant evolution of our understanding of acute PPIs.

This article seeks to compile the latest evidence on DAIR to support clinical decision-making. The recommendations presented below are derived from a comprehensive review of recent literature on the topic in sites such as PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane. These recommendations have been combined in a clear and accessible manner to facilitate their understanding and application by orthopaedic surgeons.

General aspectsIn the treatment of acute PPIs, DAIR is recognised as a less invasive procedure, with lower technical demands; lower morbidity; shorter hospital stays; greater bone preservation, and greater cost-effectiveness compared to two-stage prosthetic replacement.6 However, it is indicated in specific cases, where it can achieve infection control rates of between 12% and 80%.6 It is important to emphasise that correct patient selection is of utmost importance, considering the time elapsed since prosthetic surgery, the duration of the patient's symptoms, the type of pathogen involved and its antibiotic sensitivity, the absence of component loosening or osteomyelitis, and the absence of soft tissue or fistula involvement.

One of the key points is the duration of symptoms, which has led to considerable controversy. According to the 2018 Philadelphia International Consensus on Musculoskeletal Infections (ICM), the greatest advantage in performing DAIR has been observed in acute postoperative infections (before 4 weeks) and acute haematogenous infections.7

However, a recent study published by Van der Ende et al.,8 focused on evaluating the efficacy of DAIR treatment applied to patients at two different periods after implant surgery (those treated within the first four weeks and those treated between the fourth and twelfth week), and showed success rates of 91% and 83%, respectively. Although the knee replacement group treated later showed a lower success rate, 83% is still considered a positive result, so it could represent an effective and appropriate strategy in later cases.

After appropriate patient selection a further relevant factor for a successful procedure is understanding the technical aspects of DAIR.

Generally speaking, it is recommended to use the most lateral pre-incision to prevent vascular and closure problems. Thorough debridement with meticulous technique is required to maximise the reduction of the pathogenic load. In addition, multiple tissue samples must be taken to detect bacteria and fungi. Prolonged cultures in special or enriched media are often necessary to optimise identification of the causative microorganism, as this is essential for the success of the procedure.

Thorough and direct irrigation with various antiseptic and antibiotic solutions, such as chlorhexidine or povidone, is recommended. During the procedure, a synovectomy and meticulous soft tissue debridement should be performed, along with replacement of the modular prosthesis components when feasible. The polyethylene should be carefully removed to avoid compromising the stability of the tibial component. This can be accomplished by inserting a cortical screw into the surface of the component, applying counterpressure against the tibial implant (Fig. 1). It is important to highlight that a thorough mechanical debridement requires time and should not be carried out in a hurry, since it is a central aspect of management, with general brushing of all surfaces being a very useful tool (Fig. 2).

An assessment of the integrity and stability of the implanted components should be performed. This includes both the implant-cement interface and the cement-bone interface. The decision to retain components should be based on several factors, including: non-immunocompromised patients, low-virulence microorganisms, and short-term biofilm containment.4 Among the factors studied, obesity is recognised as a significant risk factor for PPIs of both the hip and knee. However, a clear correlation between obesity and the increased rate of failure after DAIR has not been established, as shown by Longo et al.9 in their recent systematic review. Along these same lines, Katakam et al.10 conducted a retrospective study where they suggested that patients with morbid obesity face a higher risk of DAIR failure compared to non-obese patients (57.9% vs. 36.8%, respectively). However, they concluded that this risk can be mitigated if DAIR is performed within 48h of symptom onset, confirming that timing appears to be one of the most determining factors for good outcomes.

According to the same review by Longo et al.,9 the microorganisms most frequently implicated in PPI include Staphylococcus aureus, Propionibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and other coagulase-negative staphylococci.9 Accurate identification of the causative microorganism before the procedure is highly recommended. However, this process should not delay surgical intervention once it is deemed necessary, as also suggested in the latest ICM. A delay in surgery could theoretically facilitate greater consolidation of the bacterial biofilm. Therefore, it is crucial to balance the need to identify the pathogen with the urgency of performing DAIR to optimise clinical outcomes.

The success rate of DAIR treatment in PPI varies depending on the pathogen involved. Streptococcal infections have the highest success rate (70–90%), while S. aureus infections, especially methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), have lower rates (30–60%). Infections with coagulase-negative staphylococci and gram-negative bacteria have intermediate success rates (50–70%). Polymicrobial infections and those with biofilm-forming organisms generally have lower success rates. Factors such as the speed of diagnosis, patient comorbidities, and biofilm formation also significantly influence treatment outcome.

Common intraoperative strategiesMechanical debridementThe effectiveness of mechanical debridement is arguably the most crucial factor for the success of the DAIR procedure, although it is also one of the most difficult aspects to investigate. Complete removal of devitalised and infected tissue, as well as the surrounding hypertrophic synovium, is advisable.

To ensure the eradication of infected tissue around the joint, radical synovectomy is suggested. However, it can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between infected and healthy tissue.

Afterwards, it is essential to thoroughly brush all retained non-modular components with a sterile brush, followed by adequate irrigation.

IrrigationWe found no specific clinical studies evaluating the optimal irrigation volume during DAIR for the treatment of PPIs. Despite this lack of information, we suggest following the ICM recommendation, which, based on studies providing secondary data, recommended irrigation volumes of approximately 9l.

Regarding irrigation pressure, no clinical evidence conclusively supports the specific use of high- or low-pressure irrigation. Existent suggestions are based on studies extrapolated from the management of open fractures, where there would be no significant difference at different pressures. However, we do not know if they can be extrapolated due to the possible existence of an initial biofilm. For now, we must rely on clinical experience, pending future evidence that may shed light on this aspect.

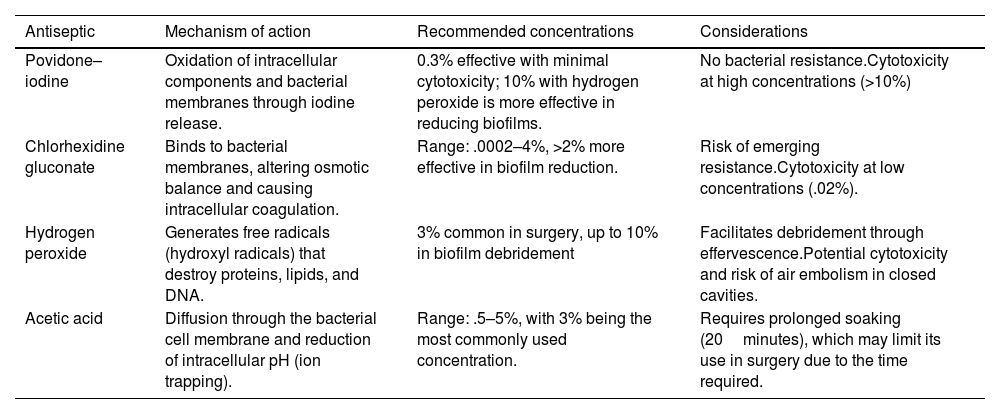

Antiseptic solutionsAlthough there is no consensus on the optimal solution, nor is there sufficient evidence on the optimal irrigation time and combination of solutions, several studies exist on the efficacy of different antiseptic solutions in eliminating bacteria from the biofilm. The authors of a recent study found povidone–iodine to be the most effective at eliminating MRSA, and acetic acid solutions to be more effective against several other organisms.11 Diluted povidone–iodine has been identified as a safe and cost-effective irrigation solution, shown to reduce the risk of infection in primary knee arthroplasty, and is also included in multiple protocols for the surgical treatment of PPI.12 Regarding lavage method, it is suggested to first perform a general pulsatile lavage with approximately 6 litres of .9% saline solution. Then, in the case of povidone–iodine, approximately 500cc to 1l of .3% solution is left on the surgical site, allowing it to act for 3–5min, followed by a second pulsatile cleansing lavage with 6l of saline solution. The suggested lavage pressure is approximately 8–12 PSI. In certain cases, it may be useful to alternate the povidone lavage with 3% hydrogen peroxide after the first lavage, which would help oxidise the bacterial cell membrane and may help eliminate more resistant microorganisms. Table 1 summarises the main antiseptics currently used in orthopaedic surgery and also provides some associated considerations.

Summary of the most commonly used antiseptics currently in traumatology, along with a summary of their mechanism of action, recommended concentrations, and some considerations that should be taken into account when using them.

| Antiseptic | Mechanism of action | Recommended concentrations | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Povidone–iodine | Oxidation of intracellular components and bacterial membranes through iodine release. | 0.3% effective with minimal cytotoxicity; 10% with hydrogen peroxide is more effective in reducing biofilms. | No bacterial resistance.Cytotoxicity at high concentrations (>10%) |

| Chlorhexidine gluconate | Binds to bacterial membranes, altering osmotic balance and causing intracellular coagulation. | Range: .0002–4%, >2% more effective in biofilm reduction. | Risk of emerging resistance.Cytotoxicity at low concentrations (.02%). |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Generates free radicals (hydroxyl radicals) that destroy proteins, lipids, and DNA. | 3% common in surgery, up to 10% in biofilm debridement | Facilitates debridement through effervescence.Potential cytotoxicity and risk of air embolism in closed cavities. |

| Acetic acid | Diffusion through the bacterial cell membrane and reduction of intracellular pH (ion trapping). | Range: .5–5%, with 3% being the most commonly used concentration. | Requires prolonged soaking (20minutes), which may limit its use in surgery due to the time required. |

Changing the surgical field after proper irrigation and debridement is a common practice, especially before the introduction of new prosthetic components. This aims to reduce bacterial load and minimise the risk of failure. However, there are no direct studies addressing its specific efficacy, so in these cases the decision is often at the surgeon's discretion. Despite the lack of evidence, we believe it is a practice that, in trained teams, is time- and cost-effective and can potentially reduce bacterial load and, consequently, reduce procedural failure.13

Regarding glove changes, there are also no studies that measure the direct effect of glove changes on the rate of PPI or DAIR failure, but there are several studies on microbiological contamination and glove perforation rates. One such study was a 2019 systematic review by Kim et al.,14 who after an exhaustive review of the literature suggested changing gloves at least once an hour, after setting up surgical drapes, before handling implants, and if a visible perforation was seen, so as to reduce contamination, as this may decrease the risk of PPI.

Modular component exchangeExchanging the polyethylene plays a crucial role, as its removal provides improved visualisation and a more optimal working field for more thorough cleaning of the posterior aspect of the knee. It also contributes to reducing the bacterial load and biofilm present on the components. Regarding the scientific evidence in this field, several studies support the idea that modular component exchange can significantly contribute to reducing PPIs, as demonstrated by Kim et al.15 in their 2015 retrospective study. Also noteworthy in this context is the multicentre review by Lora-Tamayo et al.,16 which included 349 patients with PPIs of the hip and knee caused by S. aureus. This review highlighted that modular exchange reduced the risk of failure by 33%. In this context, polyethylene exchange and modular component exchange are promising interventions, and we suggest their routine practice.

Intraoperative strategies under studyMethylene blueMethylene blue is a cationic dye with the ability to bind to bacterial biofilm. This binding enables the dye to stain areas with a higher biofilm burden, establishing it as a potentially beneficial tool for identifying areas with a higher bacterial load during surgery.

Shaw et al.17 evaluated dilute (.1%) methylene blue-guided surgical debridement in 16 patients with knee prosthesis implants during the first stage of a two-stage revision. They observed an approximately ninefold higher bacterial bioburden, as measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in the areas stained with methylene blue.

Furthermore, it has been suspected that methylene blue may have antibacterial effects that could interfere with microbial cultures. An in vitro study showed that concentrations of .05% did not affect the ability to cultivate microorganisms.18

These findings suggest a potential role for methylene blue, as it offers a visual aid during the procedure.

UltrasoundUltrasound involves an electrical current transferring its energy to a mechanical system, converting it into vibrations that generate ultrasound waves. These waves, in turn, induce vibrations in the target material, resulting in the release of particles from it.

In the exploration of new therapies, an in vitro study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of removing colony-forming units from the surface of a titanium implant. Three methods were compared: (a) debridement with pulsatile lavage; (b) exposure to ultrasound; and (c) exposure to both. Ultrasound demonstrated a reduction of approximately seven orders of magnitude, while the group receiving the combination completely eradicated viable bacteria from the biofilm.19

Furthermore, in a prospective study by Ji et al.,20 with 17 cases undergoing DAIR in addition to ultrasound, only 3 patients (6.7%) experienced recurrent infections during a mean follow-up of 9 months. Importantly, substantial additional evidence is still required before ultrasound can be routinely recommended for these procedures, but it appears to be a promising tool for future therapeutic applications.

Two-stage DAIRTwo-stage DAIR consists of performing a standard initial DAIR and, after a few days (generally 5–7 days are reported in the literature), repeating the procedure.

The results of various studies regarding double DAIR performance indicate success rates of 75–90%, exceeding historical rates for single-stage DAIR. Chung et al.5 recently confirmed this in a retrospective study involving 83 patients in which they achieved an overall success rate of 86.7%, with 89.6% in knees.

In the protocol by Chung et al., during the first phase, cultures were performed and all modular components were removed, washed, and immersed in an antiseptic solution for 3–5min (Fig. 3). A thorough irrigation and debridement procedure was then performed, including radical synovectomy, the polyethylene previously submerged in antiseptic solution was re-implanted, and high-dose antibiotic cement pearls (2–3g of vancomycin, 3.6–4.8g of tobramycin, and 2g of cefazolin; all these concentrations are given per 40g of cement used) were introduced into the joint before closure (Fig. 4). The knee was then left in an orthopaedic immobiliser. Regarding the number of pearls, it is suggested that they be approximately 2–3 doses of cement (80–120g), with pearls having a diameter between 1 and 2cm. It is also recommended to use a medium porosity cement, so as not to affect its integrity by mixing it many times with more than one antibiotic. In a second phase, approximately 5–7 days later, a second debridement was performed, the beads were removed, and new sterile modular components were implanted. Patients received intravenous and oral antibiotic treatment, along with a standard postoperative rehabilitation protocol.

This strategy can offer significant success rates in the management of PPIs. However, it is important to emphasise that each case may vary, and the choice of protocol should consider the specific characteristics of the patient and the nature of the infection.

Antibiotic therapyAntibiotic treatment after DAIR in cases of PPIs has been the subject of global debate, mainly regarding the duration, schedule, and route of administration.

Antibiotic therapy targeting specific pathogens is generally administered for 2–6 weeks after the DAIR procedure. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) suggests a duration of 4–6 weeks for patients with pathogens other than staphylococci or when combination therapy with rifampin cannot be used.21 On the other hand, the ICM recommends a minimum of 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy.7

The consensus on treatment success for PPI,22 led by Dr. Claudio Díaz, establishes that treatment failure in PPI is defined by the persistence or recurrence of the infection, the need for additional infection-related surgery, or the death of the patient as a direct or indirect consequence of the infection. This consensus provides clear and standardised criteria for assessing treatment success or failure, allowing for consistent comparison across studies and clinical guidelines.

In this context, a randomised clinical trial involving 60 patients divided participants into two groups: one received intravenous treatment for 2 weeks and the other for 6 weeks, followed by oral treatment, completing a total of 12 weeks of antibiotic therapy. A clinical cure rate of 71% and 76%, respectively, was observed in the two groups, with no statistically significant differences between them.23 Antibiotic therapy should always be prescribed based on cultures obtained, and with respect to timing, these can be divided empirically once the initial cultures are obtained.

Some studies support the implementation of long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy, extending for at least 6 months after DAIR, demonstrating a five-year infection-free prosthesis survival rate of 68.5% for the antibiotic suppression group and 41.1% for the non-suppression group.24

The addition of rifampin has demonstrated good results in staphylococcal infections.9 The ICM recommends combinations of antibiotics with rifampin for MRSA infections. However, a recent systematic review found no benefit in terms of improving treatment failure rates with adjunctive rifampin therapy, despite its widespread use in the literature.25 It is therefore important to make every effort to identify the pathogen and the subsequent antibiogram to provide a specific antibiotic regimen.

Regarding the use of intraosseous (IO) antibiotics, Kildow et al.26 recently published their results of DAIR supplemented with IO vancomycin. They observed high success rates (92.3% recurrence-free) in acute infections, but low success rates in chronic infections (44.4%). However, this study was a retrospective case series and lacked a control group. IO antibiotic administration can be performed relatively quickly and safely in the proximal tibia.

Fungal infectionsFungal infections are rare but can be very serious. The limited information available in the literature has prevented the formation of a clear consensus regarding the optimal management of these infections, with two-stage exchange being the standard conventional approach.

Overall, DAIR has been associated with a relatively high failure rate in cases of fungal infections, with reports suggesting failure rates ranging from 82% to 100%.7 However, isolated successful cases have been documented, all of which required continued antifungal treatment for a period of six months to one year after DAIR was performed.27

A recent systematic review was conducted that included 225 patients with hip or knee PPI with a fungal infection. Recurrence of infection was observed in 18.3% of patients with knee PPIs, and was more prevalent in cases of Candida albicans infection (OR: 3.56). Compared with DAIR, two-stage exchange arthroplasty was shown to be a protective factor against PPI recurrence in the knee (OR: .18).28 These results could be partly explained by the fact that patients with fungal PPIs often have immunocompromised status, which could significantly contribute to the high rate of treatment failure.

DAIR failureFactors associated with the success or failure of DAIR (ICM)Factors associated with the success of acute PPI treatment with DAIR:

- •

Replacement of modular components.

- •

Debridement within the first seven days.

- •

Addition of rifampin to the antibiotic regimen after the germ cell and antimicrobial susceptibility test are clear. After approximately 5–7 days of intravenous treatment, particularly for susceptible staphylococci, it is suggested to combine it with a fluoroquinolone. Its main function is its ability to attack the biofilm.

- •

Treatment with fluoroquinolones in cases of susceptible gram-negative bacilli.

Factors associated with failure in the treatment of acute PPIs using DAIR:

- •

Host factors: rheumatoid arthritis, advanced age, male sex, chronic kidney failure, liver cirrhosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- •

Prosthetic indication: fracture, cemented prosthesis, and prior revision.

- •

Presentation: elevated C-reactive protein, high bacterial inoculum, and bacteremia.

- •

Causative microorganisms: S. aureus, Enterococcus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter spp.

Tornero et al.29 published the KLIC score to predict DAIR failure in acute postoperative PPI and developed a risk stratification considering chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis, index surgery (revision or fracture), prosthetic cementation, and C-reactive protein >115mg/L. DAIR failure was predicted in 100% of cases with a preoperative score greater than 6, and in 4.5% of cases with a score <2.

Subsequently, Argenson et al.30 performed the same analysis in acute haematogenous PPI, publishing the CRIME80 score, which considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, C-reactive protein >150mg/L, rheumatoid arthritis, fracture as an indication for prosthesis replacement, male sex, retained mobile components, and age >80years, predicting failure with a rate ranging from 22%, increasing to 79% with a score >4. Unlike the KLIC score, the CRIME80 score has not yet been validated in an external cohort of patients.

According to the Philadelphia consensus, both preoperative scoring systems could be used in clinical practice to more accurately select patients for whom DAIR would be indicated.

Artificial intelligence has recently been incorporated into the analysis and prediction of DAIR failure. Shohat et al. analysed more than 1000 patients who underwent DAIR for acute PPI, also including the microorganism variable, creating a diagnostic algorithm with good discriminatory power to measure the success rate of DAIR. However, it lacks external quality validation.28

Options for treatment failureAfter facing complications arising from DAIR failure, the commonly recommended therapeutic strategy is to proceed with a two-stage revision arthroplasty. This technique initially involves the removal of the infected implant and the placement of a cement spacer with antibiotics. This spacer can be articulated (especially if prolonged use of the spacer is suspected) or rigid (ideal in scenarios where a second reintervention is planned early), followed by a period of treatment with initially intravenous and then oral antibiotics. This spacer releases most of its antibiotic load during the first 72h, and continues to release lesser amounts of antibiotics until approximately week 6. The second stage involves implanting a new prosthesis once the infection has been controlled. This two-stage approach is recommended to improve the chances of eradicating the infection and ensuring the long-term success of the revision arthroplasty.

Studies suggest that an initial failure of DAIR may be associated with a higher-than-expected incidence of complications in subsequent two-stage revision arthroplasty. However, a recent retrospective study on this topic involving 750 patients reported contrary results, indicating that performing a prior DAIR before a two-stage revision arthroplasty does not increase the risk of failure.31

Recommendations- I.

Patient evaluation and selection

As a general rule, in our group we try to retain prosthetic components whenever possible, provided certain conditions are met:

- A.

Acute infections, considered before 12 weeks after the initial surgery, or acute haematogenous infections (less than 2 weeks of symptoms).

- B.

Non-immunocompromised patients, ideally with an identified and treatable microorganism.

- C.

No signs of component loosening on imaging studies.

- D.

No significant soft tissue compromise in the operative area.

- II.

Double-DAIR procedure.

Once the alternative of preserving the components has been chosen, the treatment we have incorporated in recent years, following the recommendations of the Mayo Clinic group, is as follows:

- A.

Perform surgical cleansing in two stages, separated by 5–7 days.

- B.

Perform aggressive and meticulous surgical debridement.

- C.

Use a more lateral pre-incision to avoid complications.

- D.

Take multiple samples for culture using techniques and media that optimise pathogen identification.

- E.

Apply irrigation volumes of at least 9 l, using a high-pressure pulsatile irrigation system.

- F.

Use antiseptic solutions such as povidone–iodine or chlorhexidine, maintaining an “antiseptic pool” for 3–5min (Fig. 3).

- G.

Replace the modular components (insert) of the prosthesis.

- H.

Place a rosary with antibiotic-containing cement beads into the joint (Fig. 4).

- I.

Perform a thorough closure.

- J.

Maintain the knee in the interim period with an extension immobiliser.

- K.

Repeat the procedure 5–7 days later, changing the modular component (insert) again and removing the antibiotic-containing cement beads.

- L.

It is extremely important to mention that double DAIR should be a planned procedure. According to the recommendations provided above, it should never be used as a second DAIR if the first DAIR has already had poor results.

- III.

Antibiotic therapy

Regarding antibiotic therapy, we generally recommend the following:

- A.

Always base it on the cultures obtained, under the supervision of the hospital's Infectious Diseases team.

- B.

Introduce an empirical antibiotic regimen after obtaining quality cultures. The general recommendation is to combine a fluoroquinolone with a cephalosporin, although this may vary depending on the centre and local infectious epidemiology.

- C.

Treatment duration: 4–12 weeks.

- D.

Consider long-term suppressive therapy based on microbiology.

- E.

Fungal infection

- 1.

Always consider this as a possible aetiology.

- 2.

A more aggressive treatment approach such as a two-stage exchange.

- IV.

Double-DAIR failure

In case of procedure failure, we recommend the following:

- A.

Identify associated factors.

- B.

Use risk models to predict DAIR success and personalise management.

- C.

Preferably use a two-stage re-examination after a failed DAIR attempt.

The management of acute periprosthetic knee infections represents a significant challenge that impacts both patients and healthcare systems. Despite advances in surgical techniques and postoperative care, PPIs of the knee remain a significant concern due to their incidence (the leading cause of both acute and chronic revision), their associated costs, and the devastating consequences on patients’ health.

The approach known as Debridement, Antibiotics, and Implant Retention (DAIR) has emerged as a key strategy in this context, especially when implemented acutely. However, the efficacy of DAIR varies considerably, and careful patient selection, combined with meticulous surgical debridement, are crucial factors for success. This technique has better outcomes especially when a low-virulence pathogen is identified and when performed early, as well as when the patient has few comorbidities. In contexts where conditions are less than ideal, the concept of “double DAIR” emerges as an innovative strategy that seeks to improve success rates in the management of acute periprosthetic infections. The implementation of DAIR or double DAIR should be carried out in a schematic and orderly manner, considering all the elements mentioned in this paper.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical considerationsThis work is a review, and no sensitive patient information was included.

FundingNo funding was given for this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.