Necrotising fasciitis is a potentially life-threatening soft tissue infection that mainly affects the fascia and deep planes, with a very high mortality rate and severe related complications.

AimTo evaluate clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with necrotising fasciitis in our hospital and to describe their diagnostic and therapeutic management.

Material and methodsRetrospective review of medical records of 21 patients diagnosed with necrotising fasciitis with limb involvement between January 2003 and February 2021 in our hospital. Demographic data, clinical features and details of management and prognosis were collected for each patient.

ResultsOf 21 patients included, 15 were male (71.43%), with a mean age at diagnosis of 54.38±19.55 years. The most frequent comorbidities were insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in seven patients (33.33%) and a history of cancer in five patients (23.81%). Infection was monomicrobial in 14 cases (66.66%), with Streptococcus pyogenes being the most frequent microorganism; multiple pathogens were isolated in 2 patients (9.52%) and no microorganism was identified in 5 patients (23.81%). All patients underwent surgery at our hospital, with a mean of 4.14±3.98 surgeries. Only one patient underwent amputation of the affected limb. The mean hospital stay was 23.14±16.44 days, with an overall mortality of 47.62% (10 cases).

ConclusionsDespite being a rare disease, necrotising fasciitis is a very aggressive pathology, with a high mortality rate, especially in immunocompromised patients. Advanced age and oncological disease are potential factors of worse prognosis in the evolution of this condition.

La fascitis necrosante es una infección de partes blandas potencialmente letal que afecta principalmente a la fascia y a los planos profundos, con una tasa muy alta de mortalidad y de complicaciones graves derivadas.

ObjetivoEvaluar las características clínicas y demográficas de pacientes con fascitis necrosante en nuestro centro y describir su manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico.

Material y métodosRevisión retrospectiva de historias clínicas de 21 pacientes diagnosticados de fascitis necrosante con afectación de extremidades entre enero de 2003 y febrero de 2021 en nuestro centro. Se recogieron datos demográficos y clínicos del proceso y de la evaluación del manejo en cada paciente.

ResultadosDe 21 pacientes incluidos, 15 eran varones (71,43%), con una edad media al diagnóstico de 54,38±19,55 años. Las comorbilidades más frecuentes fueron diabetes mellitus insulinodependiente en 7 pacientes (33,33%) y procesos oncológicos en 5 pacientes (23,81%). La infección fue monomicrobiana en 14 casos (66,66%), siendo Streptococcus pyogenes el microorganismo más frecuente; en 2 casos (9,52%) fue polimicrobiana, y en 5 pacientes (23,81%) no se identificó el patógeno causante. Todos los pacientes fueron intervenidos en nuestro centro, con una media de 4,14±3,98 cirugías, con un único caso de amputación de la extremidad afecta. La estancia hospitalaria media fue de 23,14±16,44 días, situándose la mortalidad global en el 47,62% (10 casos).

ConclusionesPese a tratarse de una condición poco frecuente, la fascitis necrosante es una patología muy agresiva, con una elevada tasa de mortalidad, especialmente en pacientes inmunocomprometidos. Una edad avanzada y padecer un cuadro oncológico son factores potenciales de peor pronóstico en la evolución de este cuadro.

Necrotising fasciitis (NF) is a rare but potentially lethal pathological condition characterised by an infection of the skin and superficial soft tissue that tends to progress rapidly and aggressively through deeper layers, affecting fascia and muscle tissue, causing extensive necrosis that can progress to septic shock and multi-organ failure.1,2

Any anatomical region can be affected by this pathology, with the extremities, especially the lower extremities, being the area where it is most frequently seen. However, the highest mortality rate is observed in cases affecting the trunk and abdominal region.

Thanks to advances in diagnosis, surgical techniques and antibiotic options, as well as in intensive care management, the prevalence of NF has decreased over the last decades, currently standing at less than 5 cases per 100000 persons/year. However, despite this, the mortality rate remains very high, reaching more than 30% of those affected, with a range of co-morbidities and associated serious complications ranging from 20% to 40% in some series.1–7

Early diagnosis accompanied by intensive treatment with appropriate antibiotic therapy and extensive surgical debridement remain the cornerstone of NF management and are the most important factors in relation to survival and the need for amputation in patients with NF.1–5

ObjectiveTo evaluate the clinical and demographic characteristics and to describe diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients with NF in our centre.

Material and methodsDescriptive observational study based on the retrospective review of medical records of patients diagnosed with FN between January 2003 and February 2021 in our centre.

Inclusion criteriaThe study included patients with a confirmed intraoperative diagnosis of NF who had undergone surgery at our centre following a diagnosis of suspected NF obtained during initial care in the emergency department (based on clinical and analytical signs together with radiographic findings obtained by CT scan). Only those cases in which the condition affected the extremities were included in the study.

The presence of devitalised and/or necrotic fascia, the existence of purulent or dish-water pus throughout the fascial plane, as well as the absence of bleeding from the tissues during dissection1,5 were considered intraoperative diagnostic findings of NF.

Exclusion criteriaThe following were excluded from the study:

- -

Patients not operated on in our centre.

- -

Patients with a presumptive diagnosis which could not be subsequently confirmed in the operating theatre.

- -

Patients with non-localised necrotising infection of the extremities.

In those patients who met the previously indicated criteria, demographic data were collected, such as age and sex, as well as data on their previous comorbidities. A total of 21 patients were identified, of whom 15 were male (71.43%), with a mean age at diagnosis of 54.38±19.55 years (range 12–80years). Regarding comorbidities, five patients were diagnosed with hepatitisC virus (HCV) (23.81%), three patients were injecting drug users (IDUs) (14.29%), one patient was a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) carrier (4.76%), three patients had chronic alcoholism (14.29%), seven patients were insulin-dependent diabetics (33.33%) and five patients had a history of cancer with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy treatment (23.81%); in three cases (14.29%) no pathological history of interest was observed.

In each of the cases that made up our series, we determined the possible entry point, the main symptoms for which they came to the emergency department and the location of the infectious process. Regarding diagnostic management, we reviewed the data obtained in the initial blood test of each patient in the ED, calculating the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotising Fasciitis Score (LRINEC) in all cases in which the necessary data were available, including figures for leukocytes, haemoglobin, CRP, sodium, creatinine and blood glucose.5 In addition, all patients underwent urgent CT scanning prior to admission, and the images and radiological reports obtained from these tests were evaluated. The presence of gas in deep subfascial planes, the presence of collections along the fascial plane with extension of oedema to the intermuscular plane and the lack of contrast uptake in the affected fascia, a sign indicative of fascial necrosis, were considered suggestive of this.8,9

In the analysis of the therapeutic management of these patients, we determined the antibiotic treatment received during admission by each of them (both empirical initially and directed once the results of the cultures were obtained); the micro-organism identified; the number of surgical interventions they underwent; the length of hospital stay; the need for amputation or not of the affected limb, and the overall mortality.

The review of medical records for data collection and the collection of previous information was carried out using two specific computer programmes: Orion Clinic® (clinical-care information system for the hospital centres in our community), for the collection of hospital data during admission, and Abucasis® (programme that connects and integrates the centres and information systems of primary and specialised care), for the collection of information in outpatient care.

Results are shown as mean, standard deviation and absolute range for quantitative variables, while for qualitative variables they are shown as absolute frequencies.

ResultsClinical and demographic characteristicsThe most frequent region in which this condition developed was the lower limbs (16 patients [76.19%]), with 9 cases located in the thigh, 3 in the leg, 3 in the buttock area and one along the entire lower limb, from the ankle to the middle third of the thigh. Only five cases affected the upper limbs (23.81%), three of them were on the arm, one on the forearm and one on the entire upper limb, from the arm to the tips of the fingers.

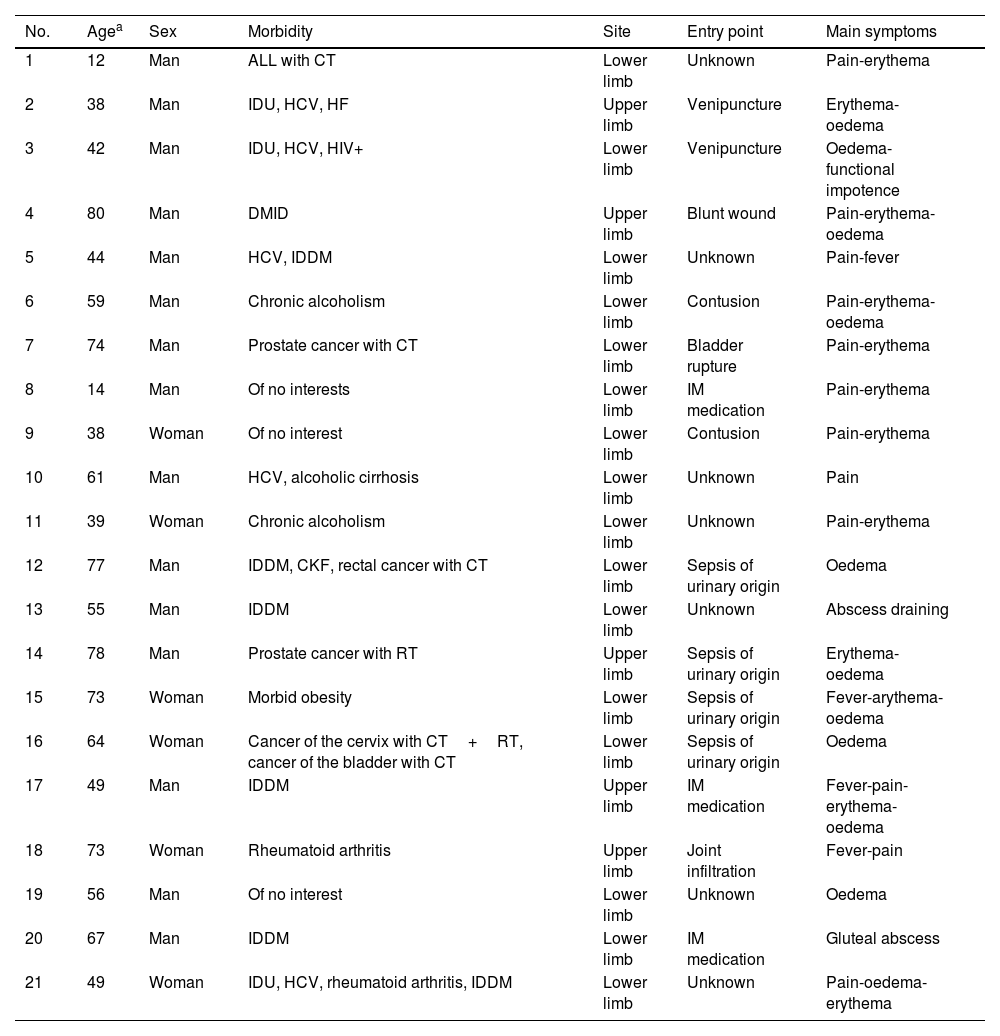

It should be noted that in four patients the aetiology of the condition was due to sepsis from a urinary source (19.05%), while two patients associated the onset of the condition with a venipuncture (9.52%) and another four with an intramuscular or intra-articular puncture for the administration of medication (19.05%). In seven cases, no clear entry point was identified (33.33%), although two of these patients were previously immunosuppressed. The main demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in this series are summarised in Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics.

| No. | Agea | Sex | Morbidity | Site | Entry point | Main symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | Man | ALL with CT | Lower limb | Unknown | Pain-erythema |

| 2 | 38 | Man | IDU, HCV, HF | Upper limb | Venipuncture | Erythema-oedema |

| 3 | 42 | Man | IDU, HCV, HIV+ | Lower limb | Venipuncture | Oedema-functional impotence |

| 4 | 80 | Man | DMID | Upper limb | Blunt wound | Pain-erythema-oedema |

| 5 | 44 | Man | HCV, IDDM | Lower limb | Unknown | Pain-fever |

| 6 | 59 | Man | Chronic alcoholism | Lower limb | Contusion | Pain-erythema-oedema |

| 7 | 74 | Man | Prostate cancer with CT | Lower limb | Bladder rupture | Pain-erythema |

| 8 | 14 | Man | Of no interests | Lower limb | IM medication | Pain-erythema |

| 9 | 38 | Woman | Of no interest | Lower limb | Contusion | Pain-erythema |

| 10 | 61 | Man | HCV, alcoholic cirrhosis | Lower limb | Unknown | Pain |

| 11 | 39 | Woman | Chronic alcoholism | Lower limb | Unknown | Pain-erythema |

| 12 | 77 | Man | IDDM, CKF, rectal cancer with CT | Lower limb | Sepsis of urinary origin | Oedema |

| 13 | 55 | Man | IDDM | Lower limb | Unknown | Abscess draining |

| 14 | 78 | Man | Prostate cancer with RT | Upper limb | Sepsis of urinary origin | Erythema-oedema |

| 15 | 73 | Woman | Morbid obesity | Lower limb | Sepsis of urinary origin | Fever-arythema-oedema |

| 16 | 64 | Woman | Cancer of the cervix with CT+RT, cancer of the bladder with CT | Lower limb | Sepsis of urinary origin | Oedema |

| 17 | 49 | Man | IDDM | Upper limb | IM medication | Fever-pain-erythema-oedema |

| 18 | 73 | Woman | Rheumatoid arthritis | Upper limb | Joint infiltration | Fever-pain |

| 19 | 56 | Man | Of no interest | Lower limb | Unknown | Oedema |

| 20 | 67 | Man | IDDM | Lower limb | IM medication | Gluteal abscess |

| 21 | 49 | Woman | IDU, HCV, rheumatoid arthritis, IDDM | Lower limb | Unknown | Pain-oedema-erythema |

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; CKF, chronic kidney failure; CT, chemotherapy; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HF, heart failure; HIV+, human immunodeficiency virus; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; IDU, injecting drug user; RT, radiotherapy.

From a microbiological point of view, in 14 cases the infection was monomicrobial, the most frequent microorganisms being Streptococcus pyogenes (6 cases), Klebsiella pneumonia and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (2 cases, respectively). In two cases the infection was polymicrobial, while in five patients the causative organism was not identified.

Therapeutic managementAll patients included were operated on at our centre, with a mean of 4.14±3.98 surgeries (range 1–15), requiring amputation of the affected limb to control the infectious focus in only one case. The patient was a 49-year-old woman with a personal history of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), RA and HCV, who presented with polymicrobial symptoms caused by Escherichia coli and MSSA with involvement of the right lower limb from the middle third of the thigh to the ankle. The patient underwent massive debridement of all affected tissue as a matter of urgency. However, given the aggressiveness of the previous resection and the residual joint instability in the knee and ankle, the patient was re-intervened at 24h to perform a supracondylar amputation, which managed to control the process without the need for further surgery.

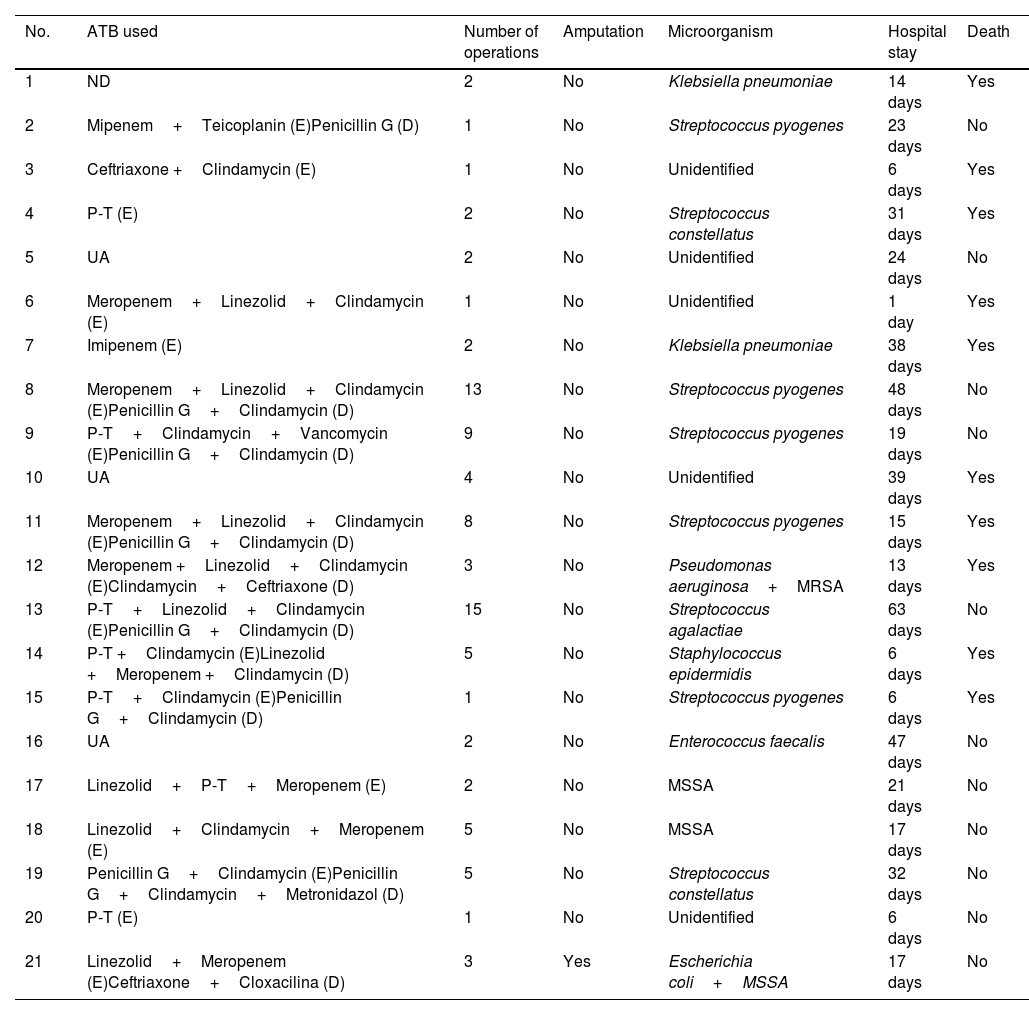

Mortality and prognosisThe mean hospital stay was 23.14±16.44 days (range 1–63 days), with overall mortality standing at 47.62% (10 cases). In one of these cases, the patient had an oncological process (acute lymphoblastic leukaemia [ALL]) which was the ultimate cause of death, with NF being a destabilising factor in the patient's condition. Table 2 shows the data on the therapeutic management, microbiological findings and prognosis of the patients included in the study.

Microbiology, treatment and evolution.

| No. | ATB used | Number of operations | Amputation | Microorganism | Hospital stay | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ND | 2 | No | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 14 days | Yes |

| 2 | Mipenem+Teicoplanin (E)Penicillin G (D) | 1 | No | Streptococcus pyogenes | 23 days | No |

| 3 | Ceftriaxone +Clindamycin (E) | 1 | No | Unidentified | 6 days | Yes |

| 4 | P-T (E) | 2 | No | Streptococcus constellatus | 31 days | Yes |

| 5 | UA | 2 | No | Unidentified | 24 days | No |

| 6 | Meropenem+Linezolid+Clindamycin (E) | 1 | No | Unidentified | 1 day | Yes |

| 7 | Imipenem (E) | 2 | No | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 38 days | Yes |

| 8 | Meropenem+Linezolid+Clindamycin (E)Penicillin G+Clindamycin (D) | 13 | No | Streptococcus pyogenes | 48 days | No |

| 9 | P-T+Clindamycin+Vancomycin (E)Penicillin G+Clindamycin (D) | 9 | No | Streptococcus pyogenes | 19 days | No |

| 10 | UA | 4 | No | Unidentified | 39 days | Yes |

| 11 | Meropenem+Linezolid+Clindamycin (E)Penicillin G+Clindamycin (D) | 8 | No | Streptococcus pyogenes | 15 days | Yes |

| 12 | Meropenem +Linezolid+Clindamycin (E)Clindamycin+Ceftriaxone (D) | 3 | No | Pseudomonas aeruginosa+MRSA | 13 days | Yes |

| 13 | P-T+Linezolid+Clindamycin (E)Penicillin G+Clindamycin (D) | 15 | No | Streptococcus agalactiae | 63 days | No |

| 14 | P-T +Clindamycin (E)Linezolid +Meropenem +Clindamycin (D) | 5 | No | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 6 days | Yes |

| 15 | P-T+Clindamycin (E)Penicillin G+Clindamycin (D) | 1 | No | Streptococcus pyogenes | 6 days | Yes |

| 16 | UA | 2 | No | Enterococcus faecalis | 47 days | No |

| 17 | Linezolid+P-T+Meropenem (E) | 2 | No | MSSA | 21 days | No |

| 18 | Linezolid+Clindamycin+Meropenem (E) | 5 | No | MSSA | 17 days | No |

| 19 | Penicillin G+Clindamycin (E)Penicillin G+Clindamycin+Metronidazol (D) | 5 | No | Streptococcus constellatus | 32 days | No |

| 20 | P-T (E) | 1 | No | Unidentified | 6 days | No |

| 21 | Linezolid+Meropenem (E)Ceftriaxone+Cloxacilina (D) | 3 | Yes | Escherichia coli+MSSA | 17 days | No |

D, directed; E, empirical; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; P-T, piperacillin-tazobactam; UA, unavailable information.

The LRINEC scale could be determined retrospectively in 18 patients. In 6 cases the value was <6 (low risk), in 4 it was 6–7 (moderate risk) and in 8 it was ≥8 (high risk). In the low-risk group, patients required 3.67 interventions on average (range 1–8) in the 25.17 days of average hospital stay (range 6–39), with 50% mortality; in the moderate-risk group, each patient underwent 5.50 surgeries on average (range 1–15), requiring an average hospital stay of 21.75 days (range 1–63), with 50% of the included patients dying; finally, in the high-risk group, the mean number of surgeries each patient underwent was 4.88 (range 2–13), with a mean hospital stay of 25.63 days (range 6–48), with a mortality of 37.5%.

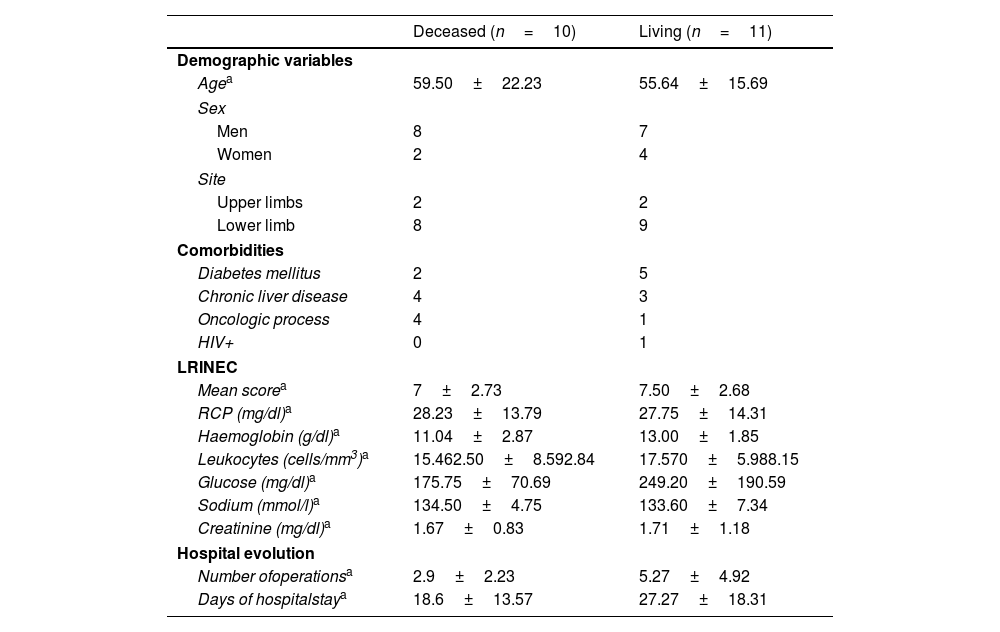

Comparison of characteristics between living patients versus deceased patientsWhen dividing the patients according to whether they were deceased or not at the time of data collection, a higher age was observed in the first group (59.50±22.23 years vs. 55.64±15.69 years), with a higher frequency of oncological processes in these patients (4 vs. 1). On the other hand, non-deceased patients had a longer hospital stay (27.27±18.31 days vs. 18.6±13.57 days), and underwent a greater number of surgeries (5.27±4.92 vs. 2.9±2.23). The distribution of the data comparing the characteristics of the deceased and living patients is shown in Table 3.

Comparison between deceased and living patients.

| Deceased (n=10) | Living (n=11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||

| Agea | 59.50±22.23 | 55.64±15.69 |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 8 | 7 |

| Women | 2 | 4 |

| Site | ||

| Upper limbs | 2 | 2 |

| Lower limb | 8 | 9 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 | 5 |

| Chronic liver disease | 4 | 3 |

| Oncologic process | 4 | 1 |

| HIV+ | 0 | 1 |

| LRINEC | ||

| Mean scorea | 7±2.73 | 7.50±2.68 |

| RCP (mg/dl)a | 28.23±13.79 | 27.75±14.31 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl)a | 11.04±2.87 | 13.00±1.85 |

| Leukocytes (cells/mm3)a | 15.462.50±8.592.84 | 17.570±5.988.15 |

| Glucose (mg/dl)a | 175.75±70.69 | 249.20±190.59 |

| Sodium (mmol/l)a | 134.50±4.75 | 133.60±7.34 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl)a | 1.67±0.83 | 1.71±1.18 |

| Hospital evolution | ||

| Number ofoperationsa | 2.9±2.23 | 5.27±4.92 |

| Days of hospitalstaya | 18.6±13.57 | 27.27±18.31 |

NF is an uncommon soft tissue infection, but with a very rapid and aggressive progression, being potentially lethal and with a high rate of associated sequelae. The appearance of this serious condition is usually related to the existence of a previous traumatic event (cuts, surgical incisions, venipunctures, administration of intramuscular or subcutaneous medication, among others), since any condition that compromises skin integrity can be a potential risk factor.

This serious condition is also often associated with the existence of diseases affecting the immune system, such as chronic liver disease, HIV, oncological processes, diabetes mellitus (DM), etc., the latter being the main one. It is estimated that the incidence of DM in patients diagnosed with FN is between 40% and 60%,1,2,10,11 with worse evolution and long-term results compared to non-diabetics.11 This latter pathology is also the main comorbidity in our series, although with somewhat lower figures (33.33%). In this situation of immune system involvement, especially the greater the state of immunosuppression, NF can develop from disseminated bacteraemia from another source.12 Thus, in four patients in our series, this serious condition developed from sepsis of urinary origin, with three of them having a history of oncological processes and the remaining patient being morbidly obese.

Tan et al.11 compared clinical findings, microbiological findings and long-term outcomes in patients affected by NF according to whether they were diabetic or non-diabetic. They found that patients with a history of DM had a higher rate of polymicrobial and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) involvement, as well as a longer delay in diagnosis, due to a more atypical clinical presentation in these patients, a longer hospital stay and a higher rate of amputation, finding no differences in mortality rate between the two groups. It is noteworthy in our series that all polymicrobial infections developed in diabetic patients, as well as the only documented case of amputation; likewise, the longest hospital stay was in a patient with a history of IDDM, being also the patient who required the greatest number of surgeries for the resolution of the condition.

Although chronic alcohol consumption is a global health problem and is found to be the aetiology of many pathologies, few studies have analysed this habit as a risk factor for NF. Notably, Yii et al.13 evaluated this relationship in a cohort study conducted in Taiwan, in which they found that the incidence of NF was more than seven times higher in patients with chronic alcoholism compared to non-alcohol consumers, and more than three times higher when adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities. They also observed that the risk of NF increased with the severity of alcoholism, thus behaving as a dose-dependent risk factor.

Several causes are attributed to these findings, the main one being immunosuppression related to chronic alcohol consumption, which leads to increased susceptibility to infection. In addition, the authors theorise an increased risk of trauma, as well as poorer adherence to treatment in these patients, leading to an increased risk of injury, a delay in consultation and in the application of appropriate therapy and, ultimately, increased disease progression.13

In our study, the male-to-female ratio was relatively high (2.5:1) compared to other published studies in which, although it has been shown to be more prevalent in males, the difference observed was not so high (approximately 1.79:1), with a mean age of 54.38 years, comparable to that reported in the literature (approximately 54.21 years). Regarding the most common anatomical site of onset of this pathology, numerous studies have shown a much more frequent involvement of the lower extremities.4,5,14,15 These results are in line with those observed in our series, with the disease developing in the lower limbs in more than 75% of cases (17 patients).

It is essential to recognise this condition at an early stage in order to be able to treat it as early as possible. However, this is difficult because initially the skin manifestations are scarce.14 The typical triad of presentation when the patient comes to the emergency department is pain, oedema and fever.9,14,15 In our series, these were the most frequent manifestations for which patients consulted.

Disproportionate pain on physical examination, as well as suspected cellulitis that does not respond to optimal antibiotic treatment, raise the suspicion of NF, especially in patients with comorbidities. The presence of haemorrhagic blisters, skin necrosis, fever, alterations in sensitivity (with paraesthesia, hypoesthesia and even anaesthesia in advanced cases), crepitus and/or generalised oedema represent the classic clinical manifestations of this condition and, together with the appearance of systemic multi-organ symptoms, such as hypotension or acute renal failure, lead almost definitively to the diagnosis of necrotising infection, allowing differentiation from cellulitis and other conditions with more superficial involvement.3 However, the appearance of these manifestations indicates an advanced stage of the condition, in which the prognosis is worse and the surgical aggressiveness required to control the condition is much higher. It is therefore essential to reach an accurate differential diagnosis before the onset of these manifestations in order to improve survival and subsequent long-term prognosis.9,14,15

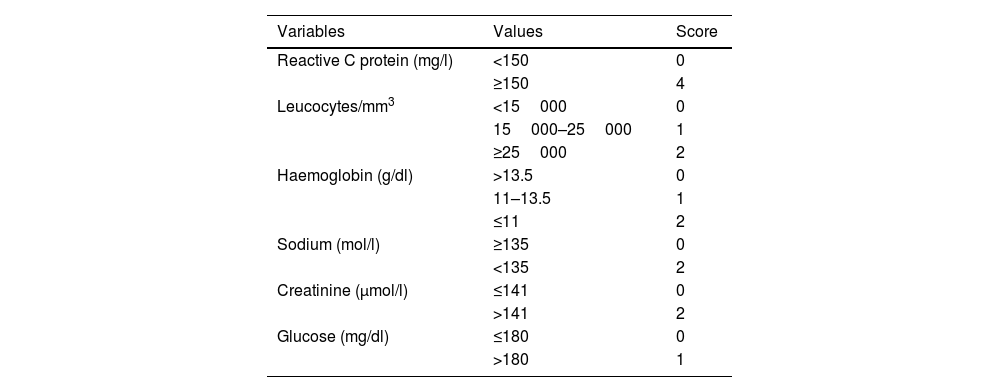

Establishing an early and accurate diagnosis of this necrotising infection is further hampered by the absence of an appropriate diagnostic tool that has demonstrated sufficient accuracy. The LRINEC scale is a multi-parametric tool based on 6 different analytical parameters (CRP, blood leukocytes, haemoglobin and serum levels of creatinine, sodium and glucose). It was developed with the aim of accurately discerning NF from other soft tissue infections in the ED, classifying the risk of necrotising infection as high, medium or low according to the values of each variable16 (Table 4). However, despite the extensive analysis of this tool in the literature, its usefulness has not been clearly demonstrated, with controversial results that question its diagnostic and prognostic accuracy.5,17–19

Scale Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotising Fasciitis (LRINEC).

| Variables | Values | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive C protein (mg/l) | <150 | 0 |

| ≥150 | 4 | |

| Leucocytes/mm3 | <15000 | 0 |

| 15000–25000 | 1 | |

| ≥25000 | 2 | |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | >13.5 | 0 |

| 11–13.5 | 1 | |

| ≤11 | 2 | |

| Sodium (mol/l) | ≥135 | 0 |

| <135 | 2 | |

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | ≤141 | 0 |

| >141 | 2 | |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | ≤180 | 0 |

| >180 | 1 |

LRINEC, low risk: <6 points; moderate risk: 6–7 points; high risk: ≥8 points.

In our series, of the 18 patients in whom the LRINEC could be calculated, 8 had a high risk (score ≥8), while up to 6 cases diagnosed with NF and with intraoperative confirmation had a low risk of developing the condition (score <6). Thus, in our study, the LRINEC scale has not been shown a priori to be an effective tool to be used alone as the only test to establish the diagnosis of NF, but as a complementary method to a high clinical suspicion reached in the emergency department by means of an accurate and thorough anamnesis and physical examination. In recent years, numerous studies have obtained similar results and have established conclusions comparable to this one.5,14,17,19

In this context, several authors have analysed the prognostic value of LRINEC in patients with a previous diagnosis of NF. Ballesteros-Betancourt et al.5 did not find a change in prognosis between medium and high levels of the LRINEC scale, although they did find a change in hospital stay, with the median number of days of hospital stay almost tripling in the group with higher values on the scale. Colak et al.20 also found that the mortality rate and the number of surgeries patients underwent were higher in the group with higher LRINEC values.

Similar findings were obtained by El-Menyar et al.,10 who observed a higher mortality and septic shock rate in patients with LRINEC ≥6, as well as a longer length of ICU stay and overall hospital stay. In addition, although they did not find differences in the number of surgeries performed in each group, patients with higher LRINEC values required a higher number of antibiotics to control the condition. The cut-off point value for predicting in-hospital mortality was 8 points on the LRINEC scale, although with moderate sensitivity and specificity values that need further evaluation.

Lau et al.21 evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of a clinical test performed in the emergency department, the finger test, in the detection of necrotising soft tissue infection. After application in the 35 patients in their series, the test showed a sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100%, with a specificity of 80% and an overall accuracy of 85.7%. Thus, the authors concluded that a negative finger test accurately ruled out necrotising infection and could avoid unnecessary aggressions in these patients, whereas a positive test required surgical intervention for examination and sampling.

Imaging tests are routinely performed in these patients as an additional diagnostic tool in emergency care. Plain radiography of the affected area is the first imaging test performed in most cases. In the early stages of the disease the findings are very similar to those identified in uncomplicated cellulitis, including thickening and increased tissue opacity. The presence of gas dissecting the deep fascial planes is a classic and quite specific sign of NF; however, it is only seen in a limited percentage of patients (estimated between 24.8% and 55%) and in advanced stages of the disease.8

CT is the main imaging modality in the management of this condition, given its wide availability and high spatial resolution compared to radiography or ultrasound. Thus, all patients included in our series underwent CT of the affected area prior to admission. Likewise, although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most sensitive test for the identification of soft tissue infection, CT is better at profiling the presence of gas in the tissues, and is more readily available and quicker to obtain than NMR.

Radiographic findings in cases of FN are similar to those seen in cellulitis, but with greater extent and severity, affecting deeper structures. A very specific hallmark finding of this necrotising infection is the presence of gas in deep subfascial planes, indicative of the presence of anaerobic organisms in the affected area. However, despite its high specificity, this finding is not present in all cases (it is only found in approximately 55% of cases) and its absence does not rule out the diagnosis if clinical suspicion is very high.

Other common features observed in this condition include dermal thickening, as well as thickening of the affected fascia, the presence of collections along the fascial plane with possible extension of oedema to the intermuscular plane, increased soft tissue attenuation, as well as lack of contrast uptake in the fascia (a finding indicative of necrosis).8,9,22,23

From a microbiological point of view, consistent with other published series,2,10,15 the most frequently identified microorganisms in our study were Streptococcus spp. (the main one being Streptococcus pyogenes) and enterobacteria. This is clearly related to the normal flora of the skin, which, through trauma, punctures or wounds, can penetrate into the deep tissues and cause soft tissue infection.2

While Streptococcus pyogenes is an important microorganism in the aetiology of this condition (especially in healthy individuals), in recent years there has been an increasing trend towards a higher prevalence of necrotising soft tissue infections caused by non-group A streptococci, particularly in immunocompromised individuals (diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, cancer, etc.).11,15 In our series, three cases of non-group A streptococci were identified, two of the hosts being insulin-dependent diabetics.

On the other hand, negative cultures (either blood cultures or intraoperative tissue samples) do not rule out the diagnosis of NF.24 In a sample of 89 patients with this pathology, Wong et al.,15 obtained negative results in 18% of cases. The authors attributed this to the introduction of empirical broad-spectrum antibiotherapy in primary care prior to sampling, which would reduce the bacterial load but would have little impact on the evolution of the primary pathology. In our series, no microorganism was detected in five patients (23.81%). However, in two of these cases the patients died so early after the first surgery that the samples obtained were not analysed and therefore no definitive results were obtained. This could represent a bias, as the above data could be overestimated with respect to reality.

Aggressive and early surgical debridement remains the cornerstone of the treatment of this pathology, with the aim of removing as much necrotic tissue as possible, including, in addition to the affected fascia, muscle, subcutaneous cellular tissue and even skin if necessary.14,15,25–27 Wong et al.15 observed in their study that a delay of more than 24h from the time of diagnosis to surgical debridement was an independent risk factor for death from this pathology.

The definitive diagnosis of NF is determined by the combination of a number of intraoperative findings (including necrotic subcutaneous tissue, absence of fascial bleeding or the presence of a purulent and often malodorous exudate throughout the fascial plane) together with histopathological examination of specimens obtained during surgical debridement. Distinctive findings of necrotising infection are the presence of necrosis of the superficial fascia, together with thrombosis of the microvasculature, fascial oedema and a polymorphonuclear infiltrate of the fascia and deep dermis.15,21,24 In our series, no intraoperative biopsy was performed in any patient, only multiple samples were taken for microbiological study.

Despite advances in surgical, antibiotic and ICU management, mortality rates in NF continue to be very high, with figures of around 30%, with some series reporting rates of over 50%.7,28 These findings coincide with those obtained in our study, in which mortality associated with this pathology was 47.62% (10 patients). The death of these patients is usually due to septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation and/or associated multi-organ failure, hence the importance of an early and accurate diagnosis that allows the establishment of appropriate antibiotic treatment and aggressive surgical debridement.14

When comparing the characteristics of the living and deceased patients in our series at the time of data collection, it is noteworthy that both age and the frequency of oncological processes were higher in the second group. Although we have not been able to establish a statistical association between these variables and mortality due to FN, we can generate the hypothesis that advanced age and suffering an oncological condition worsen the prognosis of those patients diagnosed with this pathology, and further studies are needed to analyse this relationship. On the other hand, the length of hospital stay and the number of operations undergone by non-deceased patients were higher. This is a logical finding, given that the patients who survived required more care to control their condition and to recover completely.

Our study has several limitations. The first of these stems from the retrospective nature of the study, which may have led to a loss or lack of clinical and/or analytical data collection, and we must assume that the lack of any of the data collected is due to the absence of documentation at the time of patient care. A prospective design would make such data collection more reliable, although it would possibly be difficult to design a single-centre design, given the low prevalence of this pathology. On the other hand, by using the exact diagnostic criterion “necrotising fasciitis” for the case search, there is a possibility of not having included patients with necrotising soft tissue infections who had not been admitted and/or discharged with the coded diagnosis of “necrotising fasciitis”. This could have led to a lack of data collection and thus to a lack of accuracy in the findings of our study. Finally, this is a single-centre study, and the low sample size makes it difficult to draw meaningful statistical conclusions, allowing only a description and hypothesis generation for larger studies.

ConclusionsThis study shows that, despite being a rare condition, FN is a very aggressive pathology with a high associated mortality rate, especially in immunocompromised patients. The trend observed in this series suggests that advanced age and having an oncological condition are potential factors of worse prognosis in patients with this condition, and further studies are needed to analyse this relationship and establish prognostic variables.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence V (case series).

FundingThis research did not receive any specific funding from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or not-for-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.