Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934), a distinguished histologist and Nobel Laureate in Physiology or Medicine in 1906, is considered the father of Neuroscience. However, his legacy also extended to the study of various tissues, including hyaline cartilage, an area in which he was a pioneer. Throughout his work Elements of Normal Histology and Micrographic Technique, Cajal developed fundamental concepts that, when reviewed in light of molecular biology, resonate with current ideas about cellular communication and macromolecular interactions. In particular, his observations on hyaline cartilage, such as stellate chondrocytes, were largely overlooked in the scientific literature until today. In this paper, four hypotheses based on his discoveries are proposed: the architecture of chondrocyte columns, the role of the perichondrium in endochondral ossification, cartilage nutrition, and the role of the Golgi apparatus in the resting zone. Nearly a century later, research on hyaline cartilage continues to confirm Cajal's pioneering ideas.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934), destacado histólogo y Premio Nobel de Medicina en 1906, es considerado el padre de la Neurociencia. Sin embargo, su legado abarcó también el estudio de diversos tejidos, incluido el cartílago hialino, área en la que fue pionero. A lo largo de su obra Elementos de Histología Normal y de Técnica Micrográfica, Cajal desarrolló conceptos fundamentales que, al ser revisados a la luz de la biología molecular, resuenan con ideas actuales sobre el diálogo celular y la interacción de macromoléculas. En particular, sus observaciones sobre el cartílago hialino, como las células cartilaginosas estrelladas, fueron prácticamente ignoradas en la literatura científica hasta hoy. En este trabajo, se plantean 4 hipótesis basadas en sus descubrimientos: la arquitectura de las columnas de condrocitos, la función del pericondrio en la osificación endocondral, la nutrición del cartílago y el rol del aparato de Golgi en la zona de reposo. Casi un siglo después, las investigaciones sobre el cartílago hialino continúan confirmando las ideas pioneras de Cajal.

The aim of this work is to shed light on Cajal's histological observations concerning the cartilaginous growth plate, which, until now, have not been reported in the scientific literature. His work poses questions that continue to remain valid even until the present time, and that we them in the form of four hypotheses in italics. Writing about a scientific hypothesis necessarily entails certain complications.1 The first has to do with the characteristic of the hypothesis; in our case, it is a matter of presenting an author's contribution, specifically, that of Cajal. The second complication consists of describing the hypothesis in question; in our case, the classical structure is irrelevant; we have merely to present the topic that Cajal expounds with respect to a given subject. The third is the narrative; inasmuch as Cajal's works are not readily accessible, we have copied the texts that define the appropriate topic. The fourth concerns the contributions made by other authors, which have been reduced to providing the specific information corresponding to the topic under consideration.

To present the hypotheses, it would be inappropriate to develop their structure, describe the methods of verification or design as they pertinent to each one, or to evaluate them. These hypotheses are introduced based on Cajal's texts. The working method has consisted of reviewing the texts that are quoted and presenting his observations. Inasmuch as the hypotheses are based on claims or on some statement or of a previous idea, we take the bibliographical contributions as arguments that justify the hypothesis put forth.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, histologist, studied all the tissues, including bone and cartilage in several different categories of living beings or taxa, in the various types of species, genera, families, both during the embryonic stage, as well as during different postnatal ages.2 In his textbook Elementos de Histología Normal y de Técnica Micrográfica [Elements of Normal Histology and Micrographic Technique], he described these tissues and, more specifically bone and cartilage, which comprise the focus of this work. From the very first edition of this textbook published in 1885, it has been published in successive editions and with [the author's] own contributions that are not repeated from one edition to the next over the course of 30 years.3–9

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, histologist and Nobel Prize laurate in Physiology or Medicine in 1906 regarded as the founder of current neuroscience. To understand Cajal's thinking and work, it is necessary to know the scientific environment of his time. For this, it is advisable to read the article by P. García-Barreno and J.F. Santarén.10 In order to comprehend Cajal's thinking and work, albeit succinctly, it is reflected in the report that Holmgren submitted to the Nobel Prize Committee.11 Following the work by G. Grant: “The comprehensive reports by Emil Holmgren in 1906 consisted of nearly 50 type-written pages and were based on a careful and extensive analysis of the merits of the two candidates, …” Cajal and Golgi. In Holmgren's conclusion concerning Cajal, he writes: “Cajal had made such important discoveries and had correctly interpreted his findings that they had been substantiated by others,” and concluded that “Cajal should receive the prize.” He then goes on to inform the prize committee that (translation from Swedish by G.G.): “Cajal has not served science by singular corrections of observations by others, or by adding here and there an important observation to our stock of knowledge, but it is he who has built almost the whole framework of our structure of thinking …”.11 It seems that in awarding of the Nobel Prize, Cajal's epistemological contributions were valued, as well as his histological contributions.

Epistemological contributes with respect to the theoretical foundations of histology by CajalGiven that orthopaedic surgery and traumatology comprise part of the science, we offer a glimpse of the epistemology that Cajal depicts in the prologue and in the first chapter of his magnun opus Textura del Sistema Nervioso del Hombre y de los Vertebrados [Texture of the Nervous System of Man and the Vertebrates].12 The ideas he presents pertain to the nervous system; nevertheless, they can also be applied to the study of bone and cartilage.

“The current phase of microscopic anatomy is one of renewal, from the dual perspective of fact and doctrine, it has given way to other more satisfactory interpretations, although we have also endeavoured to produce, insofar as possible, theoretical science at the present time, in histology, above all, it is impossible to disentangle the static from the dynamic. Thus, the reason for the form lies entirely in the present or past function. As for the future, the significance of a fact pertaining to structure will only be sufficiently clarified when it can answer these three questions: What useful function does this arrangement carry out in the organism? What is the mechanism of this function? By means of what chemical/mechanical processes has it become what it is in the course of the ontogenetic and phylogenic historical series?” He later goes on to offer a teleological vision of an organic system in which functional solidarity between tissues will play a major role in development.12 Cajal's thinking resonates with today's epistemology.13,14

Functional solidarity among the tissues and their involvement in the research of bone and bone and cartilage at the present time. Cajal writes: “each cell, differentiated and dedicated to a particular task, does not suffice by itself, and requires the complementary function of the companion corpuscles (cells) the membrane would have as its destination the reception of the impressions and their transmission” [sic].12 This conceptual insight by Cajal entails a relationship between tissues that will be described years later by E. Zwilling as the ectoderm/mesoderm interaction.15,16 E. Zwilling first demonstrates that the exchange between the ectoderm and mesoderm makes the development of the limb possible, with an important participation of the mesoderm.15,16 Later on, M. Gumpel-Pinot researches the ectoderm/mesoderm interaction in chondrogenesis in the chick embryo, using co-cultures and electron microscopy.17

E.D. Hay (1958) posits a new paradigm for the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT).18 The author reports that, unlike epithelial cells, mesenchymal cells have the ability to invade and migrate through the extracellular matrix, accompanying significant changes [sic]. This enables her to speculate as to the possible functional relevance of the structural changes that occur in the organelles during the course of differentiation of cartilage cells in limb regeneration.18,19

EMT transition is a biological process that enables an epithelial cell, which normally interacts with the basement membrane through its basement surface, to undergo a series of biochemical changes that allow it to adopt a mesenchymal cell phenotype, including increased migratory capacity, invasiveness, high resistance to apoptosis, and markedly increased production of EMT components.20 Completion of the EMT process is signalled by degradation of the underlying basement membrane and the formation of a mesenchymal cell that can migrate away from the epithelial layer in which it originated.20 Today, the study of these paradigms has moved from developmental embryology to molecular biology, including bone and cartilage.21,22

Presentation of the hypotheses regarding the architecture and function of the growth plate according to CajalHypothesis 1. The formation of columns of the growth plate is not a primary process, but rather a circumstantial process due to the mechanical effect of the perichondriumAccording to Cajal (1928), the architecture of the growth plate in mammalian vertebrates can be interpreted from two perspectives: one, depending on the cells’ arrangement; another, as a function of the mechanism of ossification.9

In the arrangement of cells, the process of chondrocyte division and stacking requires the movement of chondrocytes, as postulated by G.S. Dodds.23 Later on, T.I. Morales describes the rotational and sliding movements of chondrocytes in the stacking of cells in the extracellular matrix of the growth plate (Figs. 1–6).24

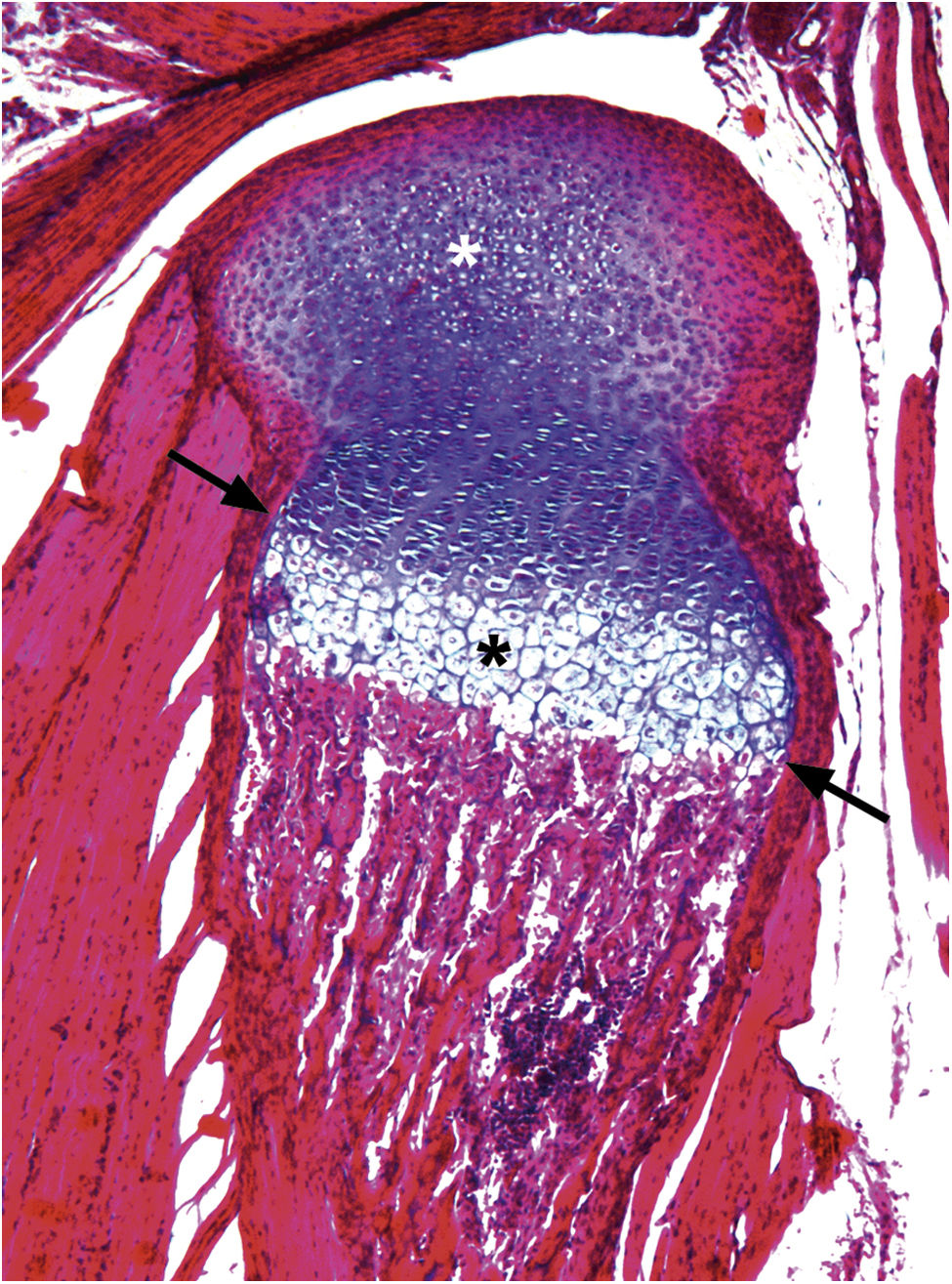

Chondroepiphysis. Sagittal section of a 5-day-old mouse tibia. R. Virchow and A. von Kölliker, contemporaries of Cajal, describe the presence of hyaline tissue at the ends of the long bones. Cajal (1889) describes the presence of tissue capsules with sphere-like, egg-shaped, and crescent-shaped cells or isogenic groups (white asterisk). The cells in these clusters can rotate in a distinct plane during their division and are distributed in columns (Cajal, 1928). At this stage, the most distal cells can be seen to be hypertrophic (black asterisk). At the periphery of the latter cells Cajal describes a perichondral bone cuff (black arrow) (paraffin section 5μm, H&E 4×).

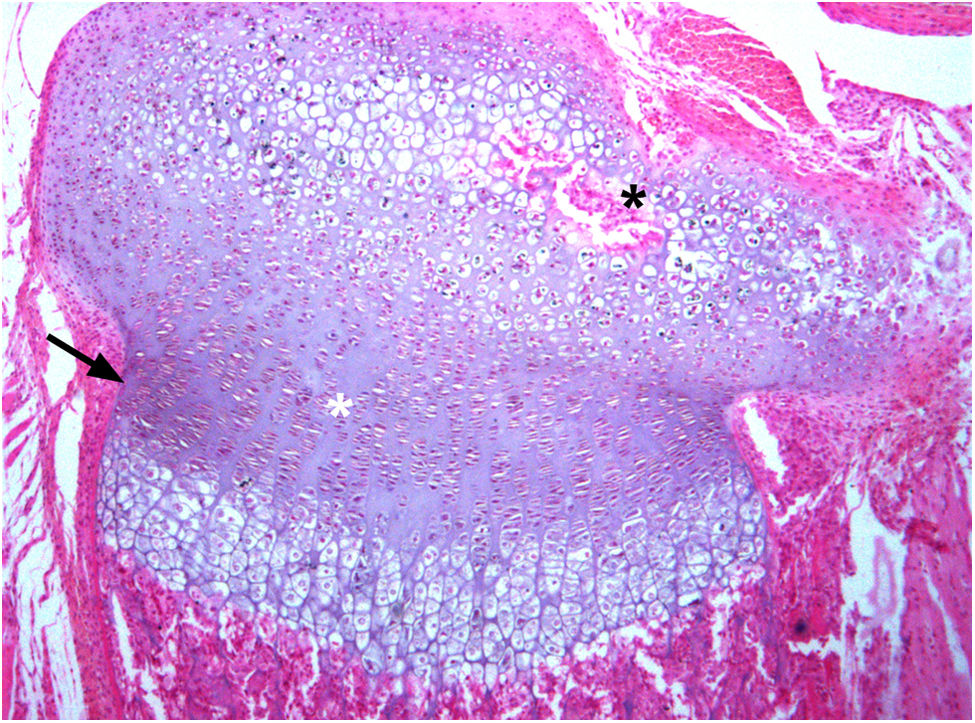

Chondroepiphysis. Frontal section of the tibia of a 15-day-old Wistar rat. Chondroepiphysis development reveals chondral canals (black asterisk) that participate in the formation of the secondary ossification centre. Isogenic clusters can be observed without a specific order (white asterisk). At the periphery of the growth plate, Cajal (1928) describes a bony cuff, today known as the ring of Ranvier (black arrow) (5μm paraffin section, H&E 4×).

Growth plate. Frontal section of the tibia of a 6-week-old Wistar rat. In the continuous development of the chondroepiphysis, a hyaline cartilage structure is clearly visible and in which Cajal (1889) writes about cells in different phases of growth: proliferating, serial cells, atrophied cells, and large chondroplasm, etc. Years later, in the 20th century, this group of cells will become known as the growth plate, and three zones are described: the reserve or resting zone (zr), the proliferative zone (zp), and the hypertrophic zone (zh). T.I. Morales (2007) outlines the process of cell rotation in the isogenic groups of the growth plate and the formation of columns of cells, and establishes a formal connection between both processes (paraffin section 5μm, H&E 10×).

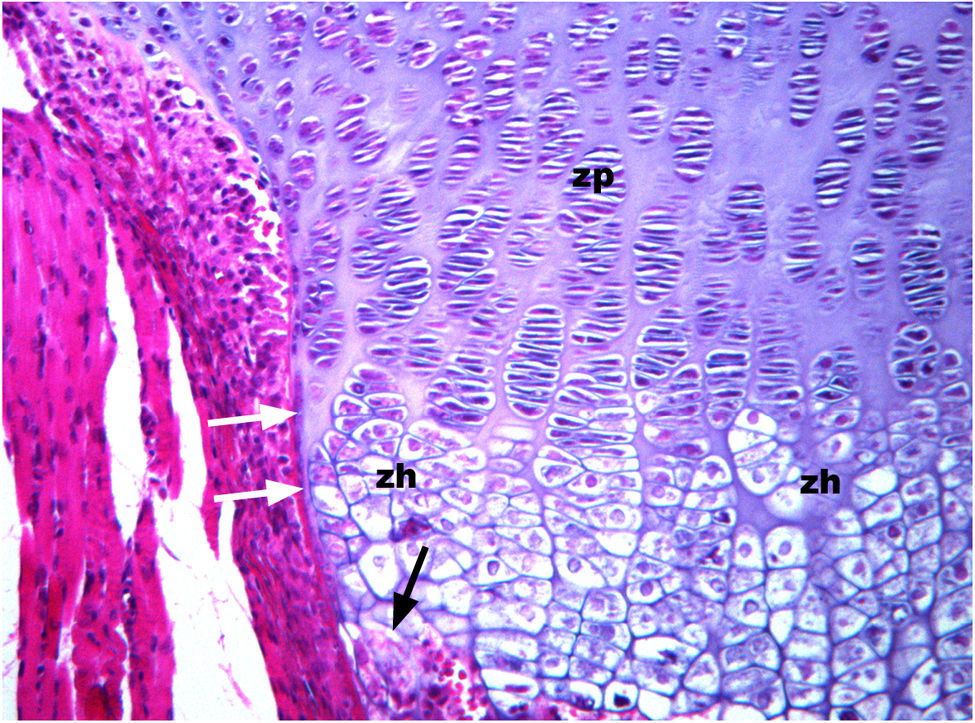

Frontal section of the bony sheath or ring of Ranvier and perichondrium in a 4-week-old Wistar rat. A discrete lamina of the bone sheath can be seen (white arrows). In the growth plate, the cells are arranged in columns, particularly in the proliferative zone (zp). However, in the hypertrophic zone (zh), the order of column formation appears to be discretely distorted. For Cajal, the formation of columns in the growth plate, unlike the columns of the clusters of cells is due to the inability of the cartilage to stretch because of the presence of the perichondral bone sheath. As for the process of endochondral ossification, Cajal (1928) states that it is put into motion by the penetration of mesenchymal cells (future transformation into osteoblasts) coming from the perichondrium into the lacuna of the hypertrophic zone in which the cell of the cartilage dies. In the image (black arrows) one can speculate as to how some cells and bone marrow elements invade empty lacunae (paraffin slice 5μm, H&E 10×).

Frontal section of the epiphysis of a 2-month-old Wistar rat. This histological preparation is presented to illustrate a function of the upper part of the growth plate. The scientific bibliography locates the resting or reserve zone (zr) in this region in the upper part of the growth plate. The resting zone is the subject of debate in the literature (M. Kazemi and J.L. Williams, 2021). Nevertheless, A.W. Ham (1954) states that this zone plays no part in the growth of the growth plate and that the junction of the growth plate does indeed take part in attaching the growth plate to the epiphyseal bone by means of bony bridges. In Figs. 5 and 6, basophilic structures (black arrows) can be seen in the resting zone (zr) in the form of columns that rise and join with eosinophilic or pinkish structures (red arrows) that correspond to the epiphyseal bone (he). This observation reveals the presence of chondro-osseous columns that connect the reserve zone with the epiphyseal bone. Technical notes: These sections have been stained using Wollbach's Giemsa stain technique. This technique is not applicable for cartilage studies. In hyaline cartilage, because of the presence of acid glycosaminoglycans and trace elements, metachromasia occurs, which can be seen by the purple colour of the growth plate. Even with the artefact, the preparation has been recovered from our histotheque because of the value of the observation (paraffin sections, 5μm, Wollbach's Giemsa stain, 4×).

Frontal section of the epiphysis of a 2-month-old Wistar rat. This histological preparation is provided to depict a function of the upper part of the growth plate. In this region, the scientific literature locates in the upper part of the growth plate the resting or reserve zone (zr). The resting zone is the subject of debate in the literature (M. Kazemi and J.L. Williams, 2021). Nonetheless, A.W. Ham (1954) states that this zone plays no role in the growth of the growth plate, and that the attachment of the growth plate to the epiphyseal bone by means of bony bridges does play a role. In Figs. 5 and 6, basophilic structures (black arrows) can be observed in the resting zone (zr) in the form of columns that emerge and link up with eosinophilic or pinkish structures (red arrows) that correspond to the epiphyseal bone (he). This observation demonstrates the presence of chondro-osseous columns that join the reserve zone with the epiphyseal bone. Technical notes: These sections have been stained with Wollbach's Giemsa stain technique. This technique is not applicable for cartilage studies. In hyaline cartilage, metachromasia occurs thanks to the presence of acid glycosaminoglycans and trace elements, which can be seen by the purple colour of the growth plate. Even with the artefact, the preparation has been recovered from our histotheque because of the value of the observation (paraffin sections 5μm, Wollbach's Giemsa stain, 4×).

Previously, R. Virchow had contributed that “the cartilage (of the growth plate) prepares for ossification from cells that increase in size, that divide rapidly and appear in large clusters; the cells lay down septa between them, which serve as an envelope. These capsules contain cells that divide and clusters of giant cells will appear, and a proliferating cartilage is produced. The cells that arise from this excessive proliferation are the ones that develop into the longitudinal axis of the bone. The cartilage then transforms into bone marrow. The second series of transformations occurs in the axial length of the cylinder, in the long bones, it is made up of bone”25 (Virchow R, 1858. Lecture XVIII, 395–426, plate on p. 411–418). R. Virchow, apropos the diagram of the growth plate, refers, in his book, to the work of A. von Kölliker (1854).26 A. von Kölliker writes that “The size and the way in which the cells of the growth plate are grouped together vary according to age and situation. As for the former (age), during embryonic life they are constantly increasing, while after birth, they appear to retain a uniform size; and with respect to the latter (situation), it can be established as a law that when the ossification of the cartilage proceeds in only one direction, the cells, at the bony edge, are arranged in rows.”26

Beginning with the studies performed by G.S. Dodds23 and by A.W. Ham27 and up to the present time,28 the criterion chosen to read the architecture of the growth plate in vertebrates has been the arrangement of the cells in columns and the criteria to define endochondral ossification are maintained.

In 1889, Cajal describes the four zones of the growth plate: the proliferative zone, which is here the first signals appear that portends the impending ossification of the cartilage in the form of a slight increase in cell volume; the serial zone; the zone of large chondroplasms; and the zone of primordial medullary spaces, in which he describes the presence of osteoblasts and osteoclasts next to a capillary.3 He also cites the presence of the perichondrium.3

Cajal details that two different processes take place within the growth plate: a) the growth processes that the chondrocytes are in charge of and b) the process of ossification that is the domain of the perichondrium (p. 383–386).9

Insofar as the plate growth process is concerned, Cajal asserts that: “[It] begins with the increased volume of the cartilage cells, as well as by the speed with which they divide”. He adds that, “as a result of the because of the lack of extensibility of the cartilage due to the perichondral bone mantle, the cell families resulting from proliferation are arranged in series or rows that run parallel and perpendicular to the plane of ossification.” (p. 386).9 Moreover, Cajal provides this description by means of figure 248, i.e. a photomicrograph of a histological section of the chondroepiphysis, in which clusters of cartilage cells with no discernible alignment can be seen in some areas; the process of ossification has begun in the metaphyseal zone; and two drawings, and Figures 249 and 250, which depict a growth plate with stacked cells, in which the process of ossification is reflected. Cajal's description indicates that the ossification process begins before the microanatomy of the growth plate begins to be structured, as is typically portrayed, in which the presence of columns of chondrocytes is described given the inability of the cartilage to extend because of the perichondral bone sleeve; the cell families that result from proliferation, are arranged in series or rows that run parallel and perpendicular to the plane of ossification.9

Cajal points out that because the perichondral bone sleeve renders the cartilage inextensible, the proliferating cell families are arranged in series or rows parallel and perpendicular to the plane of ossification 9 (p. 386). This leads to the interpretation that the formation of columns is not a primary and necessary process, but rather a circumstantial process due to a secondary mechanical effect of the perichondrium.

More recently, the paradigm of the chondrocytes arranged in the form of columns in the growth plate has been called into question.29 These authors report that in the mammalian cartilage growth plate, most of the cells (of the growth plate) failed to display the typical stacking pattern associated with column formation, which implies an incomplete rotation of the plane of division. Analyses of growth plates from postnatal mice revealed complex columns, comprised of ordered and disordered stacks of cells, that most of the cells lacked the typical stacking pattern associated with column formation, thereby suggesting an incomplete rotation of the plane of division (of the cells).29

Hypothesis 2. Endochondral ossification of the growth plate originates from the cells of the perichondriumCajal distinguishes between two types of ossification; i.e. ossification at the expense of fibrous tissue or primary ossification, and endochondral ossification or secondary ossification. In the case of endochondral ossification, bony tissue is produced by the perichondrium (p. 381–382).9 Cajal notes that the osteogenic process does not take place simultaneously throughout the entire thickness of each cartilage in the embryonic skeleton. The section of bone at a given point of ossification shows that bone is formed at the expense of perichondrium almost simultaneously, thus creating a sort of sleeve (p. 385). The capacity of the periosteum/perichondrium to lead to the appearance of the osteoblast was described by R. Virchow (1858)25 and A. von Kölliker (1854).26

With regard to the process of ossification by the perichondrium, Cajal notes that, “The deeper cells take on a polyhedral shape and adhere to the cartilage, constituting a continuous layer of periosteal osteoblasts. These osteoblasts extend into the cartilage and soon secrete a fundamental material that is akin to salts, and in which they become successively sandwiched, as in endochondral formation. Several layers of bone matter are consequently built up, in which there are cavernous spaces that communicate with the periosteum and in which capillaries and a layer of active osteoblasts are lodged.” (p. 383–384).9

During the previous phase, “a vessel penetrates from the perichondrium, accompanied by a rich entourage of embryonic connective corpuscles; its branches invade the area of the large chondroplasms, absorbing the intercavitary septa and destroying the degenerated cartilaginous cells” (p. 367–368).9 “In each medullary lacuna there is a capillary loop and a conglomerate of tiny polyhedral, fusiform or triangular corpuscles that fill the entire bone carved out in the cartilaginous base material. Among these corpuscles, which are conjunctival cells from the perichondrium. The virtue these corpuscles have of secreting the intercellular substance of the bone has earned them the name of osteoblasts.” (p. 388).9

At present, following the classical paradigm of the onset of endochondral ossification described by GS. Dodds23 and A.W. Ham,27 some authors uphold the traditional paradigm and propose that the hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiates to become an osteoblast.30 Meanwhile, there are others who posit that the hypertrophic chondrocyte signals to the perichondrium so that it differentiates into an osteoblast31 and still others claim that some perichondrial cells adjacent to the growth plate are “borderline” chondrocytes, that are capable of producing osteoblasts.32

Hypothesis 3. The growth plate is nourished by branched, plexiform fibresFrom 1886 to 1887 and later on, Ramón y Cajal studies the nutrition of cartilage in mammals, cartilaginous fish (devilfish), cephalopods (cuttlefish).33 Cajal, aware that cartilage contains no blood capillaries, contributes the conversation as to the presence of ducts or ductules, according to some, or the presence of fibres and fibrils according to others. Cajal's research demonstrates the presence of permeable fibres that start at the periphery in the perichondrium and lead to the cell capsules.33 In 1921 A-B, Cajal describes these processes more notably7 and later goes on to describe the presence of chondrogenic fibres, fibroid plates, and permeable fibres, or Budge's ducts, in preparations of the cartilage (p. 395).8

In the section dedicated to Cartilaginous Tissue, Cajal describes hyaline cartilage nutrition, typical of the cartilage that comprises the growth plate (p. 357–372),9 “The lack of vessels in the cartilage tissue undoubtedly confounds its nutrition, albeit rather lacking in its intensity. In sections of young cartilage, the basic material is crossed in certain places by relatively dense, small bundles, that we shall call permeable fibres, in allusion to their probable function. If we examine the peripheral layer of a piece of cartilage of the rib, these fibres appear to be arranged radially, beginning from the perichondrium and moving inwards to terminate in the thickness of the first capsules; in the central areas, their orientation is quite different, given that the permeable fibres form bundles which, radiating from a single capsule, extend into those of the neighbouring elements (p. 365–366).9The central branched, plexiform fibres are permeable and are capable of facilitating the diffusion of the nutritional juices”.33

R.M. Williams et al. (2007) explore solute transport in the growth plate. What is initially observed is that the tracer/florescence enters the growth plate by three routes: vessels on the epiphyseal side, vessels on the metaphyseal side, and a vascular plexus surrounding the growth plate. The first observation is that the diffusion coefficient is five times greater in the centre of the cartilage than at either edge of the chondro-osseous junction. They first describe a centripetal flow which is followed by a centrifugal flow towards the perichondrium. Blood flow is thought to be accompanied by the signalling molecules.34

From the previous paragraphs, it is clear that Cajal describes a morphological structure, fibres that stain silver without being able to rule out the possibility of a duct, which originates in the perichondrium and reaches the cell capsules.33 R.M. Williams et al. report the presence of flow that spreads between the capsules, forming a plexus between the chondrocytes, and which also arises in the perichondrium, a centripetal movement, and after spreading, a centrifugal movement towards the perichondrium is likewise described.34 Inasmuch as a two-way dialogue is established between the perichondrium and the cartilage, involving different types of signalling molecules,35 this leads us to understand that there must be two different plexuses or ducts, that join the growth plate with the perichondrium; nevertheless, these have not been described.

R. Virchow depicts a similarity between the cells and tissue of the cartilage and those of plants (Lecture I, p. 1–23)25 and, in particular, a resemblance between the cartilage of the growth plate and plant tissue, due to the distinctiveness of the faster growth of its cells (Lecture 3 XVIII, p. 35–426).25 R. Virchow's analogy between cells, tissues, and tissue function between cartilage and plant tissue suggests that the vascular tissue that serves as the source of their nutrition can also be included in this similarity. The vascularisation of plant tissues is the subject of current studies,36,37 and it is not uncommon for the description of plant vessels to be accompanied by the presence of fibres whose function has yet to be well defined.36 Plant tissue vessels exhibit one attribute, which is not described in animal tissue; specifically, during plant vascular development, individual cells fuse to create linear chains; following fusion and the formation of a secondary cell wall, these elements lose their nucleus and cell content, leaving a hollow space, a dead and finite capillary (the vessel).38 There are reports of perforations in the wall of these vessels.39 We could hypothesise that there is a vascular tissue inside the cartilage that is analogous to the plant vessel that comprises a plexus with a defined morphological structure that, in some way, can be similar to the previously described vascular pattern.

Hypothesis 4. From Cajal's work, after the study of the Golgi apparatus in the chondrocytes of the resting zone, it is possible to argue that the resting zone is not involved in the process of endochondral ossification of the growth plate9In 1921 A-B, Cajal describes two types of cells in the top part of the growth plate; one type beside the superior edge of the growth plate, consisting of small cells, some of which are isolated, while others are grouped into twos; the other type appear closer to the proliferative zone. In the latter and for the first time, he describes the Golgi apparatus in chondrocytes, although he only describes the division of the Golgi apparatus in the cells that divide in the proliferative zone.7,8

Cajal describes the presence of small cells – chondrocytes – poorly grouped, including two or three cells per group, not arranged in rows or columns, containing a small Golgi apparatus, and exhibiting no division activity. These cells along the upper edge of the growth plate are located on the first columns of the proliferative zone. This zone is described in the literature as the resting zone or reserve zone, and it is widely believed that the chondrocytes in this zone proliferate, differentiate, and become hypertrophic chondrocytes.30

In the proliferative zone, the Golgi apparatus is small and dense and also divides in each cell partition. Cajal associates the division of the Golgi apparatus with the division of the chondrocyte de la growth plate.9

In the zone of the serial cells, “The cells of each group flatten and approach each other face to face, becoming larger as they progress closer to the next zone. The Golgi apparatus gradually becomes more robust and tends to be located on one side or at the protoplasmic tip of the chondroblast. When it contains two nuclei, the Golgi apparatus is located between these two nuclei, forming a sort of equatorial plate. Finally, the protoplasm sets vacuole formation in motion” (p. 386).9

As regards the Golgi apparatus in the final phase, “Note that as we advance closer to the medullary spaces, the reticulum hypertrophies, its cords thicken and lengthen, spreading over a considerable area of the soma and encircling the central nuclear organ; finally, at the level of the last colossal chondroplasm, the Golgi network shrinks and fragments, apparently destroying itself” (p. 387).9

E.D. Hay notes the presence of the Golgi apparatus in the chondrocytes and, inasmuch as the Golgi undergoes a series of changes during the growth process and the differentiation of the cells pertaining to the growth plate.18

Cajal documents the presence of the Golgi apparatus, lacking division activity, within the chondrocytes located above the chondrocytes situated on the upper margin of the growth plate, coinciding with the first columns of the proliferative zone, and does not indicate any activity of cell division or of the Golgi apparatus in the resting zone,9 although it is now widely accepted that cell division does take place in the resting zone,30 based on an early work in which he identified the Golgi apparatus with a lectin, indicating the absence of Golgi marking in the reserve zone.40 Later, using the same methodology, he suggests that it is possible that the reserve zone is not directly involved in endochondral ossification, but may have a structural function in the cartilage in the growth plate.41

In this regard, in the contributions of R.M. Williams et al., the description of the resting or reserve zone34 is of particular interest. These authors report large radial/transverse fibres that attach the perichondrium to the epiphyseal bone; compared to the proliferative zone, in which the intrafibrillar volume fraction is minimal in comparison to the other zones of the growth plate. In contrast, the matrix of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the growth plate is relatively loose and permissive, facilitaing access to autocrine interactions between chondrocytes and paracrine interactions between chondrocytes and cells residing within the perichondrium.34 Currently, following the description of a number of functional and morphological inconsistencies described in the reserve or resting zone, it has been suggested that the microstructure of this region requires further study. In this regard, in the contributions of R.M. Williams et al., the description of the resting or reserve zone34 is striking. These authors describe large radial/transverse fibres that fix the perichondrium in the epiphyseal bone; compared to the proliferation zone, in which the intrafibrillar volume fraction is minimal compared to the other zones of the growth plate. In contrast, the matrix of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the growth plate is relatively loose and permissive, allowing access to autocrine interactions between chondrocytes and paracrine interactions between chondrocytes and cells resident in the perichondrium.34 Currently, following a number of functional and morphological inconsistencies described in the reserve or resting zone, it is suggested that the microstructure of this region needs to be studied.42

With these observations we present a succinct description of Ramón y Cajal's contributions to the study of the growth plate, with the evidence that he leaves certain unresolved questions, which deserve to be explored and included in our scientific heritage.

Conclusion- –

Hypothesis 1. The formation of columns of the growth plate is not a primary process, but rather a circumstantial process due to the mechanical effect of the perichondrium.

- –

Hypothesis 2. Endochondral ossification of the growth plate originates from the cells of the perichondrium.

- –

Hypothesis 3. The growth plate is nourished by branched, plexiform fibres.

- –

Hypothesis 4. From Cajal's work, after the study of the Golgi apparatus in the chondrocytes of the resting zone, it is possible to argue that the resting zone is not involved in the process of endochondral ossification of the growth plate.

Level of evidence I.

Ethical considerationsThis work entails no ethical considerations given that it is a bibliographic review.

FundingThis work was carried out at Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM), Ramón y Cajal Historical Archive, Medicine Library.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank José Antonio Moraleda Sobrino and María Candelas Gil Carballo, Library, Campus of Medicine, UAM and Antonio González Luengo, Technical Service. UAM.