The short stature characteristic of patients with achondroplasia can negatively affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Lower limb lengthening reusing telescopic intramedullary nails (TIMNs) offers an alternative to external fixators, with the potential to enhance functionality, self-esteem, and HRQoL, while reducing complication risks, which this study aims to evaluate.

Materials and methodsThis retrospective study included nine patients with achondroplasia who underwent parallel transverse lengthening of femurs and/or tibias reusing a TIMN between 2015 and 2022. Functionality (Lower Extremity Functional Scale, LEFS), self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale), and HRQoL (Short Form-12, SF-12, and EuroQol VAS) were assessed preoperatively and at least two years post-surgery. Complications (Clavien–Dindo–Sink classification) and patient satisfaction were also recorded.

ResultsThe median age was 13.5 years (IQR: 12.5–17.1), with a significant height increase of +19.9cm (p<0.05). Improvements were significant in functionality (LEFS, +4.6 points; p<0.05), self-esteem (Rosenberg, +3.7 points; p<0.05), and HRQoL (SF-12 physical, +8.9 points; p<0.05; EQ-VAS, +20 points; p<0.05). A total of 22 complications were reported in 32 treated bones, most classified as grade 2 or 3B, with no significant correlation to outcomes in functionality, HRQoL, or self-esteem outcomes (p>0.05).

ConclusionsLower limb lengthening reusing TIMNs appears to improve functionality, HRQoL, and self-esteem in patients with achondroplasia compared to their preoperative status. High patient satisfaction and manageable complications were observed, with no negative impact on outcomes, laying the groundwork for future studies.

La talla baja característica de pacientes con acondroplasia puede afectar negativamente la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS). El alargamiento de miembros inferiores reutilizando clavos intramedulares telescópicos (CIMT) ofrece una alternativa a los fijadores externos, con el potencial de mejorar la funcionalidad, autoestima y CVRS, mientras reduce el riesgo de complicaciones, objetivo principal de este estudio.

Material y métodosEste estudio retrospectivo incluyó a 9 pacientes con acondroplasia que se sometieron a alargamiento paralelo transverso de fémures y/o tibias reutilizando un CIMT entre 2015 y 2022. Se evaluaron la funcionalidad (Escala de Función de Extremidad Inferior [LEFS]), la autoestima (Escala de Rosenberg) y la CVRS (Short Form 12 [SF-12] y EuroQol VAS) preoperatoriamente y al menos a los 2 años poscirugía. Además, se registraron las complicaciones (sistema Clavien-Dindo-Sink) y la satisfacción.

ResultadosLa mediana de edad fue de 13,5 años (RIC: 12,5-17,1), con un aumento significativo en la estatura de +19,9cm (p<0,05). Se observaron mejoras significativas en la funcionalidad (LEFS, +4,6 puntos; p<0,05), autoestima (Rosenberg, +3,7 puntos; p<0,05) y CVRS (SF-12 físico, +8,9 puntos; p<0,05; EQ-VAS, +20 puntos; p<0,05). En total, hubo 22 complicaciones en 32 huesos tratados, la mayoría clasificadas como grado 2 o 3B, sin correlación significativa con los resultados en funcionalidad, CVRS o autoestima (p>0,05).

ConclusionesEl alargamiento de miembros inferiores con CIMT parece mejorar la funcionalidad, CVRS y autoestima en pacientes con acondroplasia en comparación con su situación preoperatoria. La satisfacción es alta y las complicaciones son manejables, sin impacto negativo en los resultados, sentando las bases para futuros estudios.

Achondroplasia is the most common cause of non-lethal skeletal dysplasia, characterized by rhizomelic and disproportionate short stature. It is defined by short limbs, macrocephaly, and bone deformities, leading to significant functional and psychosocial complications.1 The average height of adults with achondroplasia—130cm in men and 124cm in women2— together with associated skeletal comorbidities, significantly impacts daily quality of life. It imposes physical and architectural barriers, hinders social integration, and affects self-esteem.3 In recent years, the development of medical treatments such as vosoritide has opened new possibilities for stimulating bone growth in these patients. Although data on its efficacy and safety with mid-term follow-up are available, its high cost, estimated at $320,000 annually (or $200,000 per centimetre of growth), limits accessibility and widespread use.4,5

Given these limitations, limb lengthening surgery remains a therapeutic option to increase height in patients with achondroplasia.6 This procedure provides a more functional height, and improved body proportionality, and may also enhance self-esteem and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), as reported by patients themselves.7,8 Several studies have shown that increased height facilitates mobility, reduces the need for physical adaptations, and promotes better social integration, thereby increasing personal and psychological satisfaction.9 The introduction of telescopic intramedullary nails (TIMNs) has revolutionised limb lengthening, offering significant advantages over traditional external fixators,10–12 such as a lower complication rate, greater patient comfort, and improved aesthetic perception, which translates into higher levels of satisfaction after surgery13-17. However, in patients with achondroplasia, whose bones are shorter, the use of TIMN is limited by their elongation capacity (maximum 5cm), which is insufficient for the growth needs of these patients.

In 2022, the first study documenting the use of TIMN for lower limb lengthening in patients with achondroplasia was published, employing an innovative strategy that involved reusing the same device to perform two sequential lengthenings. This technique has shown promising results in terms of local safety and efficacy.18 Nonetheless, questions remain regarding the functional impact of the procedure, as well as on quality of life, self-esteem, and patient satisfaction, which are the central objectives of this study.

MethodsThis retrospective study, conducted at a national paediatric orthopaedic referral centre, included all patients with achondroplasia who underwent bilateral transverse femoral and/or tibial lengthening by reusing a TIMN18 between 2015 and 2022. Approval was obtained from the centre's Ethics Committee (no. R-0001/22). Exclusion criteria were prior lengthening surgery on the same bone, bone deformities that prevented intramedullary nailing, and incomplete medical records.

Surgical intervention and lengthening protocolThe surgical procedure and lengthening protocol have been described previously.18 An initial lengthening of 5cm was performed, followed by reusing the same nail, unlocking it, rewinding it, and relocking it for a second lengthening of up to an additional 5cm, reaching a maximum total of 10cm per bone (Fig. 1). All surgical procedures were performed by a team specialised in extremity reconstructive surgery, composed of two highly experienced orthopaedic surgeons (JAH and CMG). During the lengthening process, patients were evaluated by rehabilitation specialists and received formal physical therapy. Additionally, they were advised to perform daily home mobility exercises for the hip, knee, and ankle, with the goal of preventing contractures and optimising functional outcomes. A total of 9 patients were included in the study group: 7 underwent bilateral lengthening of both segments (femurs and tibias), while 2 patients underwent bilateral femoral lengthening only. A total of 32 bones were treated: 4 isolated femurs and 28 combined bilateral femoral and tibial procedures (non-simultaneous). Additionally, 3 patients underwent humeral lengthening using an external fixator. However, these procedures were not included in this analysis. The minimum follow-up for all patients was 2 years after the last intervention.

Assessment of resultsPatients were evaluated preoperatively and at least two years after surgery. These evaluations were routinely performed in the clinics and included the following:

- •

Functionality was assessed using the Lower Extremity Function Scale (LEFS), which includes 20 questions on the ability to perform daily tasks.19

- •

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was used to measure patients’ positive and negative feelings about their self-image and self-competence.20

- •

HRQoL was measured using the Short Form 12 (SF-12) Health Survey,21 which measures the physical and mental components of health, as well as the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS)22 to measure perceived quality of life.

- •

Satisfaction was assessed using four qualitative questions, focusing on overall satisfaction with the procedure and results, willingness to undergo the procedure again, perceived improvement in quality of life, and recommending the procedure to other patients. Patients were also asked whether they were now able to perform activities that were previously impossible due to their height, or whether they performed them with greater ease.

Additionally, anthropometric data, including weight (kg), height (m), and body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) before and after lengthening, were recorded. Complications were classified according to the modified Clavien–Dindo–Sink (MCD) system for orthopaedic procedures.23

Statistical analysisAll data were statistically analysed using SPSS version 23 software (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous quantitative data were described as median and interquartile range (IQR), appropriate for small sample sizes, while categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage values. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare pre- and postoperative outcomes for functionality, HRQoL, self-esteem, and patient satisfaction. Likewise, the relationship between complications, classified according to the MCD system, and changes in the different assessment scales was assessed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. All tests were two-tailed, with a significance level set at p=.05.

ResultsThe median age of patients at the time of the first intervention was 13.5 years (IQR: 12.5–17.1 years), with 4 female and 5 male patients. Following the procedures, a significant increase in both weight and height was observed (p<.05), with the height increase being more pronounced. As a result, the BMI did not show a statistically significant change (p>.05) (Table 1). The median follow-up from the first intervention was 6 years (IQR: 5.3–7.7 years). At the end of the follow-up, the median age of the patients was 21 years (IQR: 18.5–25.9 years).

Pre- and postoperative anthropometric results.

| Parameter | Pre- | Post- | Change | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 39.0 (30.2–51) | 48.0 (36–55) | +9.0 | <.05 |

| Height (m) | 121.0 (115–133) | 140.0 (134–157) | +19.0 | <.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 (20–38.5) | 24.5 (17.9–27.9) | −1.22 | >.05 |

Data are presented as median and interquartile range. Comparative analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

BMI: body mass index.

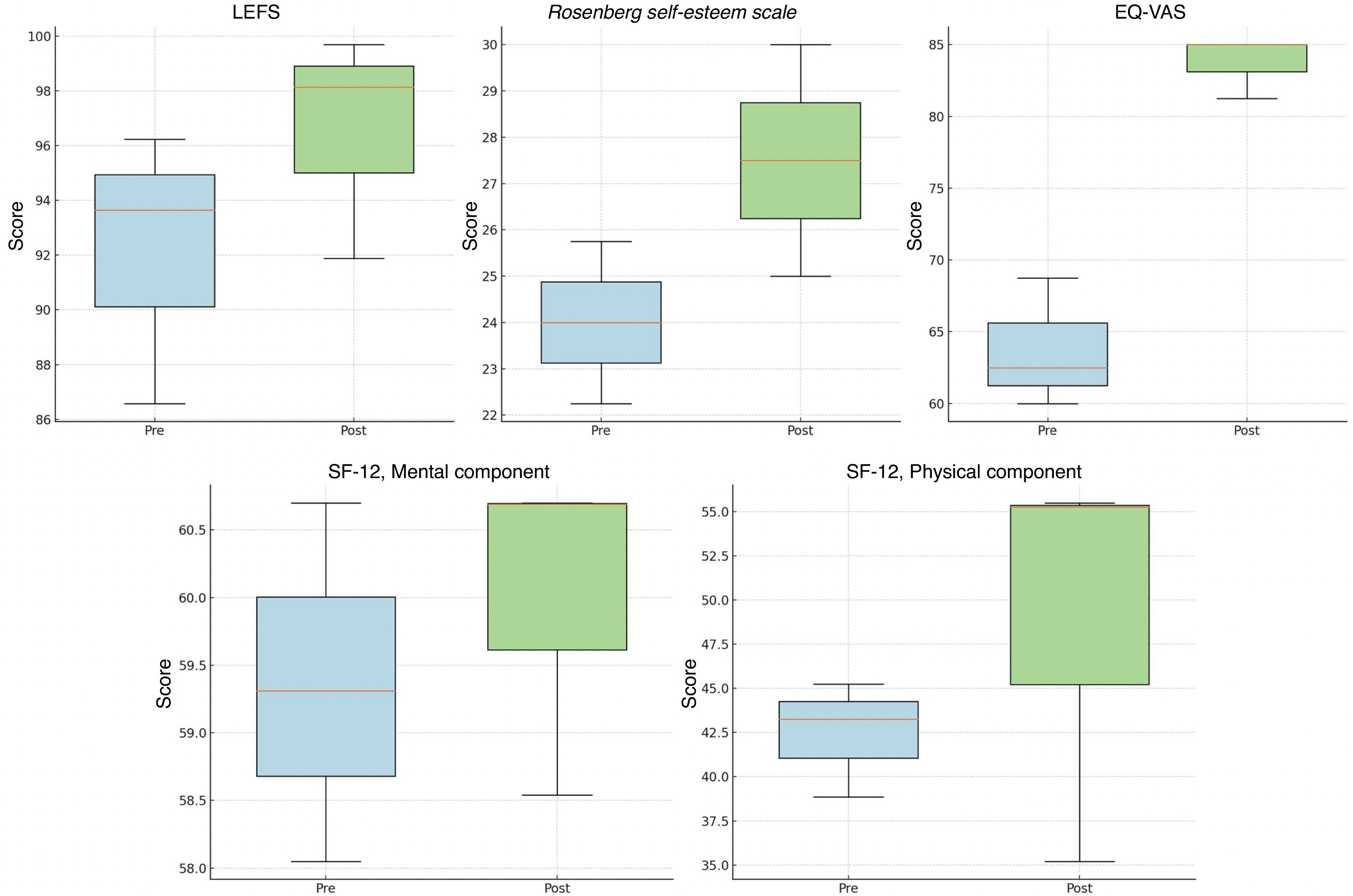

Significant improvements were observed in functionality, as assessed by the LEFS, after the procedure (p<.05) (Table 2, Fig. 2,). Self-esteem, assessed using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, also showed significant improvement, with an increase of 3.7 points (IQR: 2.0–4.0; p<.05) after the procedure (Table 2, Fig. 2). Similarly, HRQoL, measured using the SF-12 and the EQ-VAS, showed significant improvements. On the physical component of the SF-12, the median score increased by 8.9 points (IQR: 6.0–12.3; p<.05), whereas the mental component showed a modest change of .2 points (IQR: −.1 to 4.0; p>.05). The EQ-VAS score improved significantly by a median of 15 points (IQR: 10–20; p<.05) (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Results from the different functionality scales, HRQoL and self-esteem.

| Pre- | Post- | Cambio | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEFS | 85 (51.2–96.3) | 97.5 (58.8–100) | +4.6 | <.05 |

| Rosenberg self-esteem scale | 22 (22–26) | 25 (24–30) | +3.7 | <.05 |

| SF-12, physical component | 37.5 (28.7–46.3) | 46.3 (35.2–55.5) | +8.9 | <.05 |

| SF-12, mental component | 55.5 (55.3–60.5) | 60.7 (57.8–62.4) | +.2 | >.05 |

| EQ-VAS | 60 (60–70) | 80 (65–85) | +15 | <.05 |

Data are presented as median and interquartile range. Comparative analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

HRQoL: health-related quality of life; EQ-VAS: Euroqol Visual Analogue Scale; LEFS: Lower Extremity Function Scale; SF-12: Short Form 12.

Overall patient satisfaction was high across all dimensions assessed. All indicated that they would be willing to undergo the procedure again and would recommend it to other patients in similar circumstances. Furthermore, all participants reported a significant improvement in their quality of life after lower limb lengthening. The activities they reported being easier to perform included reaching for objects on high shelves, asking for information at counters, climbing high curbs more easily, riding a bicycle, driving, and participating in sports such as basketball or volleyball. They also mentioned improvements in household tasks, such as accessing high cabinets and using previously inaccessible appliances, such as the microwave or the top shelves of the refrigerator.

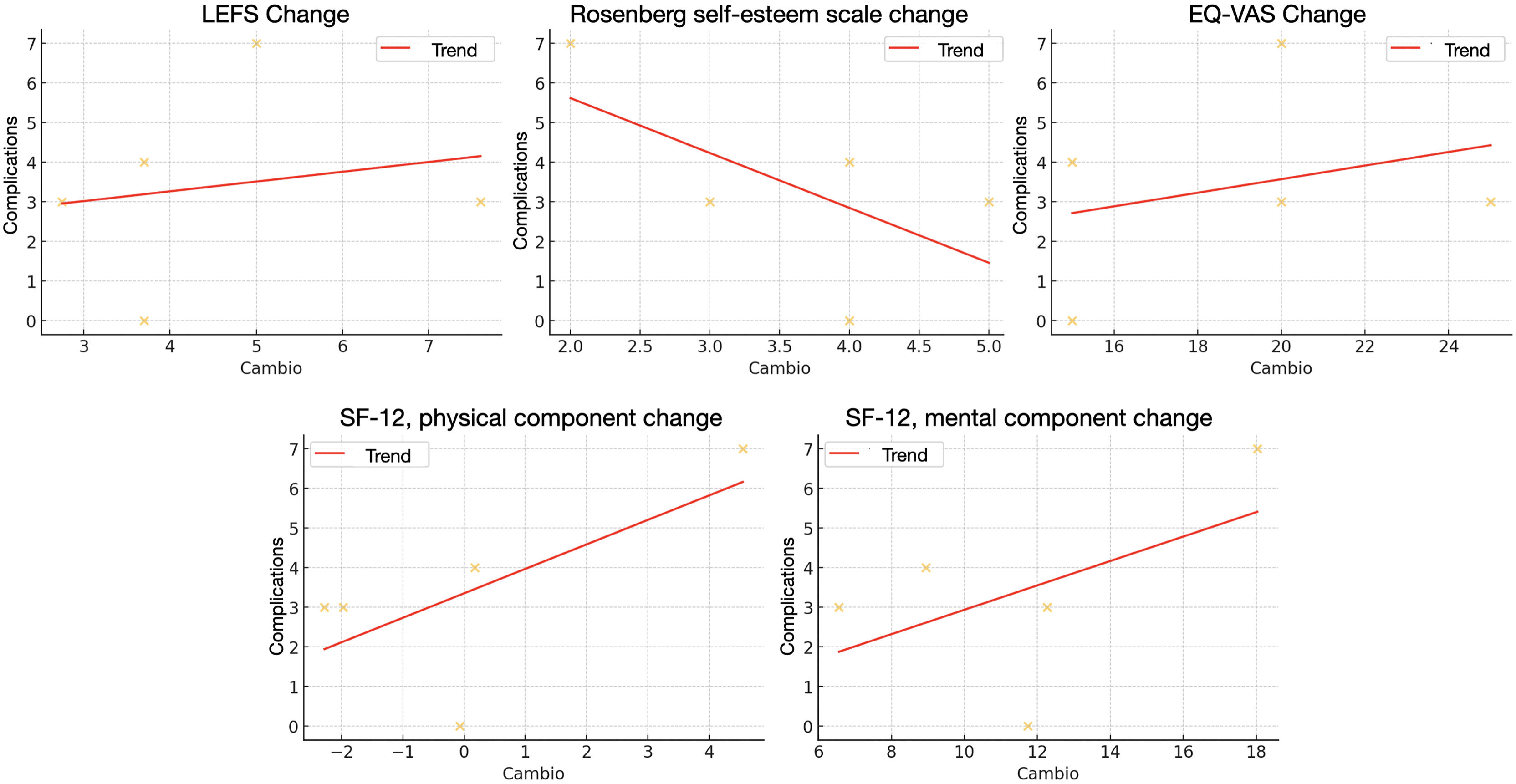

ComplicationsA total of 26 complications were recorded in the 32 bones that underwent lengthening, representing a complication rate of 81.3%. Since 8 bones presented more than one complication, 53.1% of the bones suffered at least one complication. Of these, 5 were grade 1, 11 were grade 2, and 10 were grade 3B, with no grade 4 or 5 complications reported (Appendix B, Supplementary Table 1). No significant correlation was found between the occurrence of complications and changes in functionality, HRQoL, or self-esteem 2 years after the procedure (Table 3, Fig. 3). This suggests that, despite complications, patients did not experience a significant negative impact on their final outcomes.

Correlation between the scales of results and the complications.

| Correlation | p | |

|---|---|---|

| LEFS Change | .19 | .77 |

| Rosenberg self-esteem scale change | −.63 | .26 |

| SF-12, physical component change | .53 | .36 |

| SF-12, mental component change | .67 | .21 |

| EQ-VAS change | .29 | .64 |

Analysis performed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. A value of 1 indicates a perfect positive correlation, −1 indicates a perfect negative correlation, and 0 indicates no linear correlation.

EQ-VAS: Euroqol Visual Analogue Scale; LEFS: Lower Extremity Function Scale; SF-12: Short Form 12.

The results of this study demonstrate that lower limb lengthening with TIMN in patients with achondroplasia appears to improve functionality, self-esteem, and HRQoL in the medium term, with manageable complications that did not negatively impact outcomes. This is the first study to document these benefits using TIMN instead of external fixators, providing initial evidence and establishing a foundation for future studies.

Lower limb lengthening with TIMN appears to improve patients’ functional capacity, as measured by the LEFS scale, facilitating daily activities with fewer adaptations. Previous studies have shown that greater height reduces physical barriers such as reaching high objects or walking long distances unaided.8,24 Our patients also reported improvements in activities such as cycling, stepping up on curbs, or driving. This increase in height, by facilitating previously difficult or impossible activities, contributed to greater independence and participation in social activities.25,26

HRQoL also improved significantly in our study, as physical and psychological barriers to daily living were reduced. Previous studies maintain that limb lengthening improves HRQoL in patients with achondroplasia7,8,27 and that taller stature correlates with better HRQoL.28 Increased height facilitates social integration and decreases the need for adaptations, allowing for fuller participation in environments designed for average-height individuals.8,26 Validated questionnaires show that patients who undergo surgery report significantly higher HRQoL scores than those who do not, and compared to their own preoperative scores.24,26

Furthermore, increased height has a positive impact on self-image, improving confidence and reducing the perceived difference from peers, which facilitates greater social acceptance. Studies have shown that patients with increased height experience improvements in self-esteem as visible differences with average-height individuals are reduced.7,29 Reducing the perception of difference facilitates more natural social integration, reduces feelings of insecurity, and mitigates the stigma associated with short stature.8 Notably, this benefit is not limited to lower limbs, as significant improvements in self-esteem have also been observed after upper limb lengthening.30

TIMN lengthening is associated with greater satisfaction compared to external fixators, as its reduced visibility reduces emotional and social stress, improving emotional well-being and increasing satisfaction with the procedure.15 Furthermore, the absence of pins that pierce the skin and muscles reduces the risk of infection and pain with mobilisation, facilitating more comfortable and effective rehabilitation and resulting in improved ranges of motion.17,31 Overall, patients who undergo TIMN lengthening report a more positive experience and more satisfactory long-term results.15

Several studies have shown that TIMN lengthening reduces the risk of complications in non-achondroplastic populations.16,17 In our study, although complications were observed in 53.1% of the 32 lengthened segments, most were manageable and did not affect mid-term functionality or HRQoL. No patients presented superficial or deep infections, skin problems, or clinically relevant length discrepancies, which contrasts with previous studies with external fixators, where these complications are more frequent and negatively affect HRQoL, postoperative satisfaction, and increase hospital readmissions.32,33 In our series, one fracture was recorded upon nail removal, treated with re-nailing. Fractures of regenerated bone are more common with external fixators,34,35 and some authors recommend using prophylactic intramedullary nails after external fixator removal.36 The lower incidence of fractures with TIMN is attributed to the greater stability and alignment it provides, in addition to the comfort and less invasiveness that allow the device to remain in place during healing, reducing the risk of fractures.

Our study has some limitations. The small sample size limits generalizability to the entire achondroplasia population. Furthermore, the retrospective design introduces potential biases in data collection, and the lack of a control group limits comparisons with other treatment approaches, such as external fixators or non-lengthening. We did not perform a detailed analysis of anthropometric variables (e.g., body proportionality indicators or skeletal comorbidities), nor did we stratify height, weight, and BMI into standard deviations specific to achondroplasia. This may have provided more context and improved data interpretation. Furthermore, the use of generic questionnaires not specific to the achondroplasia population is another limitation, so the findings should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the 2-year follow-up period may not be sufficient to fully assess long-term complications or the sustainability of improvements in functionality, HRQoL, and self-esteem. These limitations highlight the need for prospective studies with a larger cohort, specific tools for the achondroplastic population37 and longer-term follow-up to confirm these results and explore the long-term impact of these procedures.

ConclusionsLower limb lengthening with TIMN in patients with achondroplasia appears to improve functionality, HRQoL, and self-esteem compared to the preoperative situation. Satisfaction is high, and complications are manageable, with no negative impact on outcomes, underscoring the safety and efficacy of TIMN as a technique for lower limb lengthening in these patients.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

AuthorshipSubstantial contributions to the conception or design of the study; or to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for it: MGO, JAH, CMG, JGF, RMEG, APQ.

Drafting the study or revising it critically for important intellectual content: MGO, JAH, CMG, JGF, RMEG, APQ.

Final approval of the version to be published: MGO, JAH, CMG, JGF, RMEG, APQ.

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the study, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: MGO, JAH, CMG, JGF, RMEG, APQ.

Informed consentAll the participants gave their informed consent prior to study participation.

Ethical approvalInstitutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study (no. R-0001/22). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

FundingThis project received financial support from the Alonso Family Foundation and the SECOT Foundation, which significantly contributed to the development of this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article to declare.

We sincerely thank the Alonso Family Foundation and the SECOT Foundation for their help and support in the development of this study. We would also like to thank the patients and their families for their collaboration in the functionality and quality of life assessments performed during follow-up.