To assess the perioperative management of haemostasis and transfusion practices in adult patients undergoing craniotomies.

MethodOnline questionnaire addressed to Spanish anaesthesiologists and promoted by the Neurosciences and Haemostasis, Transfusion Medicine and Fluid Therapy Sections of SEDAR. The questionnaire was sent by email and social media, and was active between June and October 2022.

ResultsWe obtained 155 responses from 67 centres; 59.4% perform >100 craniotomies per year. 61.7% were regularly involved in neuroanaesthesiology. Only 21.9% of respondents had pre-anaesthesia assessment performed by a member of that section, and in most of them (83.0%) the assessment was performed ≤3 weeks in advance. Of the respondents with Patient Blood Management programmes, 58.2% had no specific protocols for craniotomies. 90.3% reported that haemoconcentrates are systematically reserved. A lower platelet limit of 100,000/µL is considered acceptable by 76.8%. 99.4% of respondents discontinued antiplatelet medication based on half-life. Only 23.9% respondents routinely discontinued non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The transfusion threshold for haemoglobin during surgical bleeding was <10 g/dL in 18.7%, <9 g/dL in 38.1%, <8 g/dL in 38.7% and <7 g/dL in 4.5%.

ConclusionsPreoperative anaemia screening and treatment programmes are not implemented and blood product reserves are systematised in patients scheduled for craniotomy. Anti-aggregation therapy is discontinued according to the half-life of the drug without checking platelet functionality.

Conocer el manejo perioperatorio de la hemostasia y la práctica transfusional en pacientes adultos intervenidos de craneotomía.

MétodoCuestionario online dirigido a facultativos españoles de Anestesiología e impulsado por la Sección de Neurociencias y de Hemostasia, Medicina Transfusional y Fluidoterapia de la SEDAR. El cuestionario fue enviado por correo electrónico y redes sociales, y estuvo activo entre junio y octubre del 2022.

ResultadosObtuvimos 155 respuestas de 67 centros; el 59,4% realiza >100 craneotomías al año. Un 61,7% se dedicaba de forma habitual a la neuroanestesiología. Solo en un 21,9% la evaluación preanestésica es realizada por un miembro de esa sección, y en la mayoría de las respuestas (83,0%) la evaluación se realiza ≤3 semanas de antelación. De los encuestados que disponen de programas de Patient Blood Management, un 58,2% no tenían protocolos específicos para craneotomías. Un 90,3% reportó que se hace reserva de hemoconcentrados de forma sistemática. Un 76,8% considera aceptable un límite inferior de plaquetas de 100.000/µL. El 99,4 % de los encuestados suspendían la medicación antiplaquetaria basada en la vida media. Solo 23,9% encuestados interrumpían sistemáticamente los antiinflamatorios no esteroideos. El umbral transfusional de la hemoglobina durante el sangrado quirúrgico fue <10 g/dL en 18,7%, <9 g/dL en 38,1%, <8 g/dL en 38,7% y <7 g/dL en 4,5%.

ConclusionesNo se aplican programas de detección y tratamiento de la anemia preoperatoria y se sistematiza la reserva de hemoderivados en pacientes programados para craneotomía. Se suspende la terapia antiagregante según la vida media del fármaco sin comprobar la funcionalidad plaquetaria.

The management and control of intracranial bleeding is of vital importance in neurosurgery, and transfusion may be required to maintain cerebral oxygenation, promote homeostasis, and avoid consumptive coagulopathy. In addition to local measures, it may be necessary to administer coagulation factors, platelets and drugs such as desmopressin and antifibrinolytics to maintain haemostasis.1

For various reasons, there is as yet no consensus in the literature on which to base definitive evidence-based guidelines on transfusion practices during craniotomy. First, the balance between anaemia and coagulopathy creates a complex neuropathophysiology that is affected by both the type and location of the tumour or vascular lesion to be treated. It is also essential to bear in mind that transfusion of autologous or donor blood is highly restricted in patients with malignant tumours.2,3 Secondly, the increasing complexity of neurosurgical procedures, especially in patients with vascular malformations, increases the risk of bleeding. In addition to this, patients undergoing these procedures are increasingly older, more likely to present comorbidities and, in many cases, will be receiving anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet therapy that further complicate the clinical scenario. Finally, point-of-care testing (POCT) techniques such as thromboelastography (TEG) and platelet function analysis have recently been added to the existing arsenal of conventional coagulation laboratory tests. These technological innovations have added a new dimension to diagnosis and patient management.4

Routine clinical practice in neurosurgery varies considerably among anaesthesiologists in Spain, raising the need for a national survey to determine current trends in perioperative management and transfusion practices, the technology available for monitoring haemostasis, and the extent to which these factors have been protocolised in Spanish hospitals. The results of this survey will lay the foundation for improvements in patient blood management programmes for patients undergoing craniotomy.

Material and methodsMembers of the Neuroscience Division and the Haemostasis and the Transfusion Medicine and Fluid Therapy Division of the Spanish Society of Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR) developed a 43-item questionnaire to evaluate the perioperative management of haemostasis and current transfusion practices in adult patients undergoing craniotomy in hospitals across Spain (Appendix A).

The questionnaire was posted on social media (Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn) and sent by email to SEDAR members, the heads of anaesthesiology and neuroanaesthesia services between June and October 2022. Two promotional campaigns were launched, one in June and the other in September.

The target recipients were anaesthesiologists working in public or private hospitals in Spain where neurosurgical procedures are performed. All were asked to respond responded individually and anonymously. Before completing the questionnaire, respondents were asked to give their express consent to take part in the study.

The questionnaire contained different structural and organizational questions on the number of craniotomies performed per year in the hospital, the pre-anaesthesia visit, the assessment of preoperative haemostasis, the intraoperative monitoring of haemostasis and coagulation, and the use of drugs and blood-derivative before, during, and after surgery.

The questionnaire contained a mix of ratio scale, multiple choice, and open-ended questions. The internal validity was tested by the authors and the external validity was tested by 10 subjects who had not participated in the design of the questionnaire.

AnalysisThe responses were coded and a computerized database was created for the purpose of analysing the data on SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Only qualitative variables were analysed in this study. Frequency tables were used to perform the univariate analysis and the Chi-square statistical test was used for the bivariate analysis.

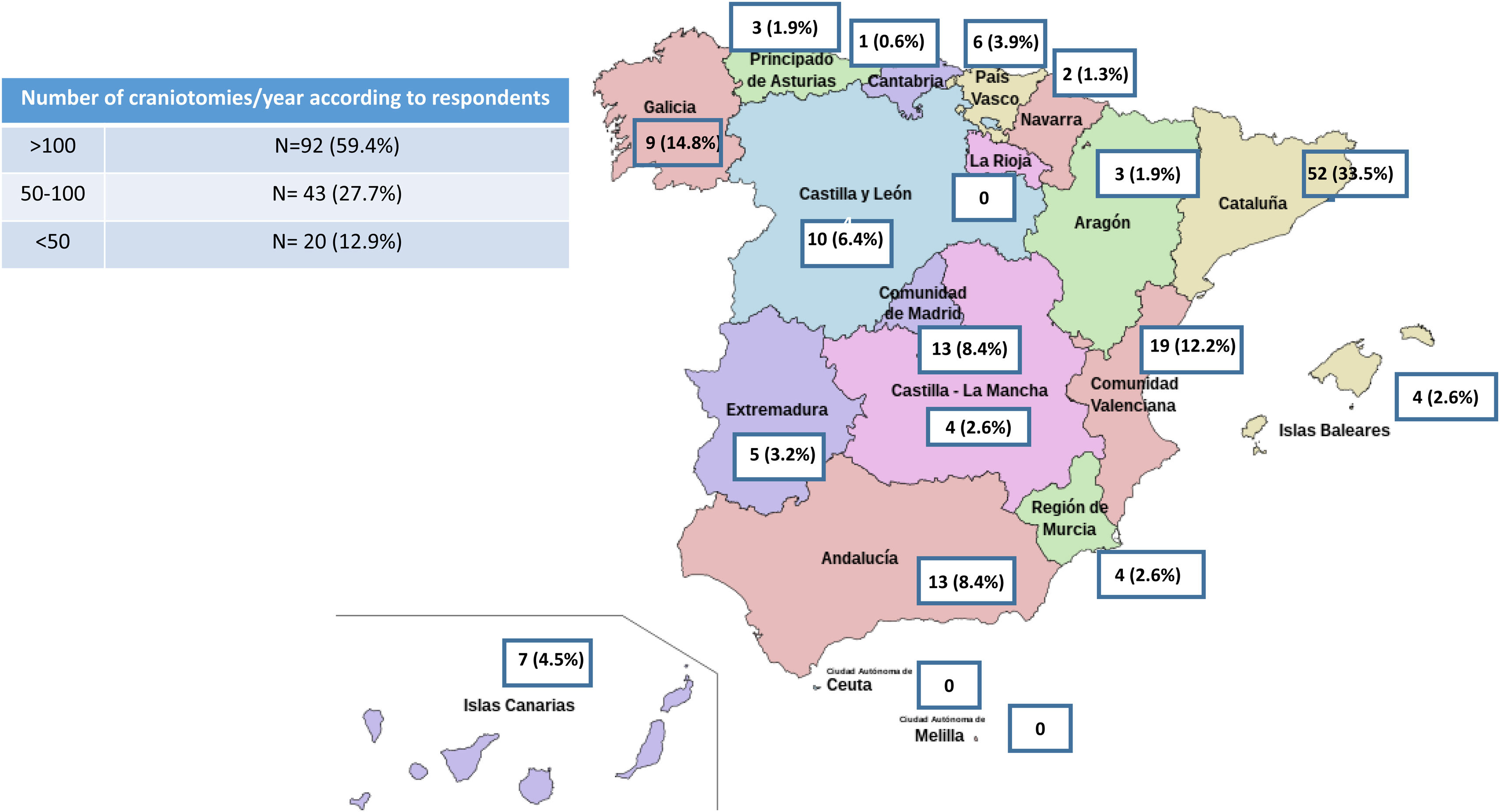

ResultsA total of 155 responses were obtained from 67 health centres (in 29 cases more than one questionnaire was returned from the same centre) in 16 autonomous communities. The results of the survey are shown in Appendix B. Over half (61.7%) of the anaesthesiologists polled regularly work in neuroanaesthesiology 59.4% performed more than 100 craniotomies per year in their hospital, 27.7% performed between 50 and 100 craniotomies per year, and 12.9% performed fewer than 50 craniotomies per year (Fig. 1).

Preoperative periodOnly 21.9% of respondents replied that a member of the neuroanaesthesia team performed the preoperative assessment. In most cases (83.0%), the interval between the preoperative assessment and surgery was 3 weeks. Only 38.7% of respondents asked questions about bleeding abnormalities during the pre-anaesthesia assessment. In 65.6% of cases, estimated blood loss was noted on the surgery request form. Nearly all (90.3%) respondents replied that blood was routinely pre-ordered in their hospital; in 67.1% of cases, this was done by the neurosurgeon. In most cases (80.5%), two bags of red blood cell were ordered

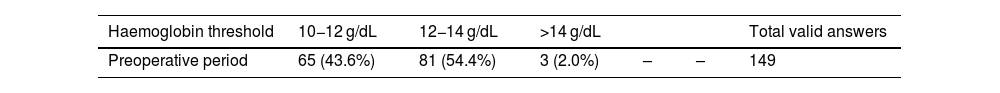

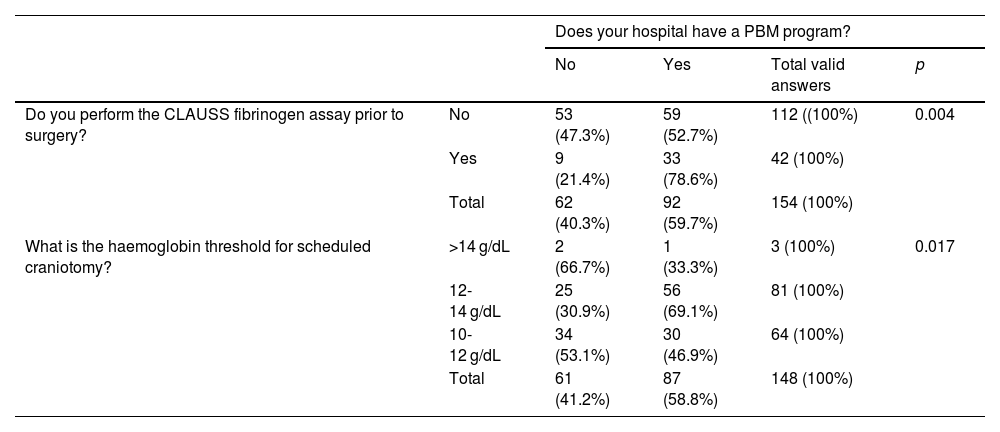

PBM programmes were used by 59.7% of respondents; however, the majority responded that there was no protocol for this type of intervention (58.2%). The haemoglobin (Hb), platelet, and fibrinogen levels accepted by respondents prior to a scheduled craniotomy are shown in Table 1. In hospitals with a PBM program, the acceptable Hb range for scheduled craniotomies was predominantly 10 −12 g/dL (30.9% vs 69.1%; p = 0.017). A total of 72.9% of respondents do not take into account the Clauss fibrinogen level prior to surgery (Table 2).

Haemoglobin, platelet and fibrinogen level thresholds in the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative periods.

| Haemoglobin threshold | 10−12 g/dL | 12−14 g/dL | >14 g/dL | Total valid answers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative period | 65 (43.6%) | 81 (54.4%) | 3 (2.0%) | – | – | 149 |

| Transfusion threshold | <7 g/dL | <8 g/dL | <9 g/dL | <10 g/dL | Total valid answers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative period | 7 (4.5%) | 60 (38.7%) | 59 (38.1%) | 29 (18.7%) | – | 155 |

| Postoperative period | 6 (3.9%) | 72 (46.8%) | 52 (33.8%) | 24 (15.6%) | – | 154 |

| Platelets | >150,000/µL | >100,000/µL | >70,000/µL | >50,000/µL | Rotem | Total valid answers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative period | – | 119 (76.8%) | 32 (20.6%) | 4 (2.6%) | – | 155 |

| Preoperative (Antiplatelet + urgent) | – | 119 (77.8%) | 27 (17.6%) | 7 (4.6%) | – | 153 |

| Intraoperative perioda | 1 (0.6%) | 78 (50.7%) | 46 (29.9%) | 11 (7.1%) | 62 (40.3%) | 154 |

| Postoperative period | 2 (1.3%) | 68 (44.2%) | 61 (39.6%) | 23 (14.9%) | – | 154 |

| Fibrinogen | >2.5 g/L | >2.0 g/L | >1.5 g/L | Rotem | Total valid answers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative period | 17 (11.3%) | 97 (64.2%) | 37 (24.5%) | – | – | 151 |

| Intraoperative perioda | 9 (5.8%) | 60 (40.0%) | 55 (35.7%) | 87 (56.5%) | – | 154 |

| Postoperative period | 4 (2.6%) | 71 (47.0%) | 76 (50.4%) | – | – | 151 |

Availability of patient blood management programs and the haemoglobin threshold for scheduled craniotomy.

| Does your hospital have a PBM program? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total valid answers | p | ||

| Do you perform the CLAUSS fibrinogen assay prior to surgery? | No | 53 (47.3%) | 59 (52.7%) | 112 ((100%) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 9 (21.4%) | 33 (78.6%) | 42 (100%) | ||

| Total | 62 (40.3%) | 92 (59.7%) | 154 (100%) | ||

| What is the haemoglobin threshold for scheduled craniotomy? | >14 g/dL | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (100%) | 0.017 |

| 12-14 g/dL | 25 (30.9%) | 56 (69.1%) | 81 (100%) | ||

| 10-12 g/dL | 34 (53.1%) | 30 (46.9%) | 64 (100%) | ||

| Total | 61 (41.2%) | 87 (58.8%) | 148 (100%) | ||

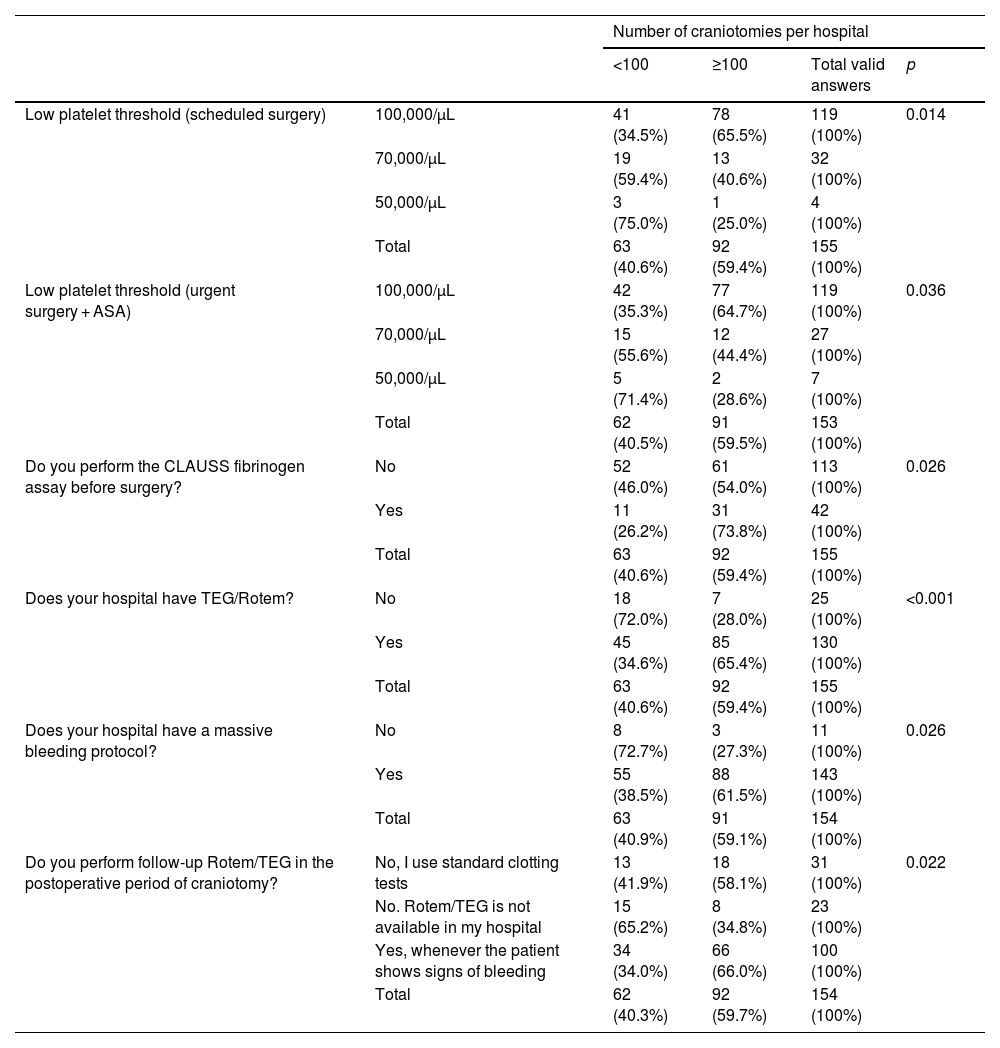

In hospitals that performed more than 100 craniotomies per year compared to those with fewer than 100 craniotomies per year, the acceptable platelet ranges for a scheduled intervention were higher (34.5% vs 65.5%; p = 0.014), pre-intervention fibrinogen was more frequently measured (54.0% vs 73.8%; p = 0.026), thromboelastometry (ROTEM)/thromboelastography (TEG) was more frequently available (28.0% vs 65.4%; p < 0.001), and massive bleeding protocols were more frequently in place (27.3% vs 61.5%; p = 0.026) (Table 3).

Volume of craniotomies performed (hospitals performing < 100 vs ≥ 100), platelet threshold for scheduled surgery, preoperative fibrinogen assay, availability of Rotem/TEG, availability of a massive blood transfusion protocol, use of Rotem/TEG in the postoperative period.

| Number of craniotomies per hospital | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <100 | ≥100 | Total valid answers | p | ||

| Low platelet threshold (scheduled surgery) | 100,000/µL | 41 (34.5%) | 78 (65.5%) | 119 (100%) | 0.014 |

| 70,000/µL | 19 (59.4%) | 13 (40.6%) | 32 (100%) | ||

| 50,000/µL | 3 (75.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 4 (100%) | ||

| Total | 63 (40.6%) | 92 (59.4%) | 155 (100%) | ||

| Low platelet threshold (urgent surgery + ASA) | 100,000/µL | 42 (35.3%) | 77 (64.7%) | 119 (100%) | 0.036 |

| 70,000/µL | 15 (55.6%) | 12 (44.4%) | 27 (100%) | ||

| 50,000/µL | 5 (71.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 7 (100%) | ||

| Total | 62 (40.5%) | 91 (59.5%) | 153 (100%) | ||

| Do you perform the CLAUSS fibrinogen assay before surgery? | No | 52 (46.0%) | 61 (54.0%) | 113 (100%) | 0.026 |

| Yes | 11 (26.2%) | 31 (73.8%) | 42 (100%) | ||

| Total | 63 (40.6%) | 92 (59.4%) | 155 (100%) | ||

| Does your hospital have TEG/Rotem? | No | 18 (72.0%) | 7 (28.0%) | 25 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 45 (34.6%) | 85 (65.4%) | 130 (100%) | ||

| Total | 63 (40.6%) | 92 (59.4%) | 155 (100%) | ||

| Does your hospital have a massive bleeding protocol? | No | 8 (72.7%) | 3 (27.3%) | 11 (100%) | 0.026 |

| Yes | 55 (38.5%) | 88 (61.5%) | 143 (100%) | ||

| Total | 63 (40.9%) | 91 (59.1%) | 154 (100%) | ||

| Do you perform follow-up Rotem/TEG in the postoperative period of craniotomy? | No, I use standard clotting tests | 13 (41.9%) | 18 (58.1%) | 31 (100%) | 0.022 |

| No. Rotem/TEG is not available in my hospital | 15 (65.2%) | 8 (34.8%) | 23 (100%) | ||

| Yes, whenever the patient shows signs of bleeding | 34 (34.0%) | 66 (66.0%) | 100 (100%) | ||

| Total | 62 (40.3%) | 92 (59.7%) | 154 (100%) | ||

Nearly all (99.4%) respondents reported that the antiplatelet interruption interval was calculated on the basis of the drug's half-life and the last dose, without performing any specific test (point-of-care testing such as VerifyNow™). Regarding anti-inflammatories, 35.2% interrupted them on a case by case basis, and 40.8% never interrupted them. The strategy in patients undergoing urgent craniotomy under treatment with antiplatelet agents varied considerably, although the most prevalent practice (32.7% of respondents) was prophylactic administration of platelets if the preoperative count was below 100,000/µL (Appendix B).

Successful reversal of anticoagulants before scheduled surgery was confirmed by determining the drug half-life in 51.6% of cases, and by INR in 86.5%. Only 7.1% of respondents performed the anti-Xa assay, which evaluates the activity of seraum FXa inhibitors (new anticoagulants).

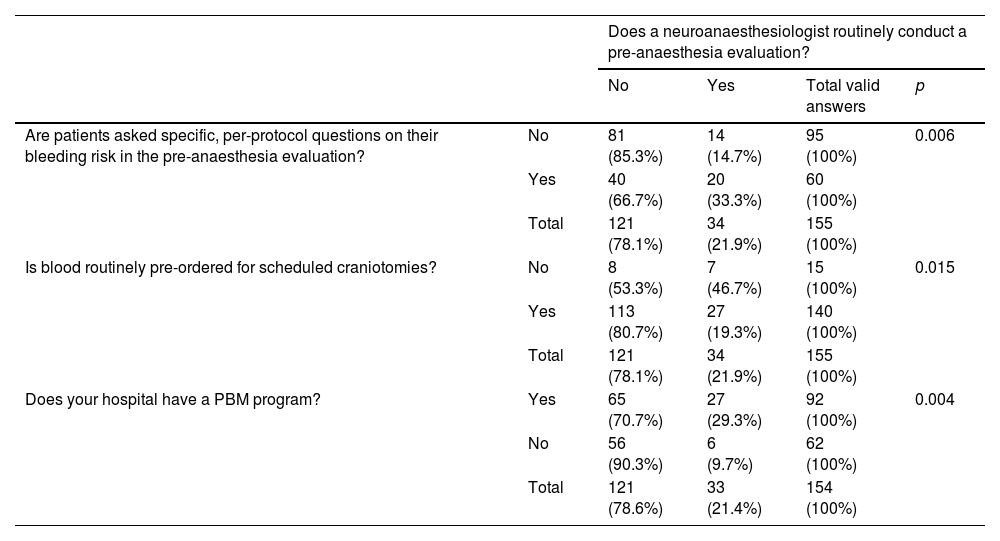

In hospitals in which a member of the neuroanaesthesia team performed the pre-anaesthesia evaluation, a significantly higher percentage of patients were asked specific questions to rule out an unknown coagulation disorder compared with hospitals in which team members did not evaluate perform the pre-anaesthesia assessment (33.3% vs 14.7% p = 0.006). Differences in routine pre-ordering of blood were also observed (19.3% vs 46.7% p = 0.015) (Table 4).

Pre-anaesthesia evaluation conducted by a neuroanaesthesiologist and per protocol. questions on bleeding risk, routine pre-ordering of blood, and availability of a PBM protocol.

| Does a neuroanaesthesiologist routinely conduct a pre-anaesthesia evaluation? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total valid answers | p | ||

| Are patients asked specific, per-protocol questions on their bleeding risk in the pre-anaesthesia evaluation? | No | 81 (85.3%) | 14 (14.7%) | 95 (100%) | 0.006 |

| Yes | 40 (66.7%) | 20 (33.3%) | 60 (100%) | ||

| Total | 121 (78.1%) | 34 (21.9%) | 155 (100%) | ||

| Is blood routinely pre-ordered for scheduled craniotomies? | No | 8 (53.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | 15 (100%) | 0.015 |

| Yes | 113 (80.7%) | 27 (19.3%) | 140 (100%) | ||

| Total | 121 (78.1%) | 34 (21.9%) | 155 (100%) | ||

| Does your hospital have a PBM program? | Yes | 65 (70.7%) | 27 (29.3%) | 92 (100%) | 0.004 |

| No | 56 (90.3%) | 6 (9.7%) | 62 (100%) | ||

| Total | 121 (78.6%) | 33 (21.4%) | 154 (100%) | ||

Most (77.3%) respondents stated that the bleeding risk is read out loud during the Surgical Safety Checklist. Most respondents checked the availability of blood bags before inducing anaesthesia in patient at high risk of bleeding (appendix B).

The Hb, platelet, and fibrinogen thresholds for transfusion during intraoperative bleeding are shown in Table 2. Nearly all (92.9%) respondents replied that their hospital had a massive bleeding protocol. Most (91.0%) were unaware of the incidence of intraoperative transfusion for craniotomies in their hospital, and in many hospitals (62.6%) cell savers are not available. Most respondents stated that ROTEM/TEG was available in the surgical suite, and 69.5% administer tranexamic acid in persistent or difficult-to-control bleeding, regardless of the results of thromboelastometry. Most respondents (73.5%) follow a permissive hypotension strategy in patients with persistent or difficult-to-control bleeding, although they were not asked to describe the exact strategy used. Among respondents using permissive hypotension, 78.9% replied that they determined the acceptable limit on a case by case basis. Intraoperatively, continuous core temperature was routinely monitored by most respondents (Appendix B).

Postoperative periodThe transfusion thresholds for Hb, platelets and fibrinogen in the postoperative period of craniotomy in a stable patient are shown in Table 1. Most respondents do not routinely correct postoperative prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), or INR levels, and most would also consider performing Rotem/TEG in the postoperative period of craniotomy if there are signs of bleeding (Appendix B).

Only 10.4% of respondents did not use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) for postoperative pain management (metamizole was considered an NSAID). The drug combinations most frequently used were: paracetamol, metamizole and opioids/opiates (44.8%); paracetamol, metamizole, dexketoprofen and opioids/opiates (16.9%); paracetamol, dexketoprofen and opioids/opiates (10.4%); paracetamol and opioids/opiates (7.8%); and paracetamol, metamizole and dexketoprofen (7.8%) (Appendix B).

DiscussionMost of the anaesthesiologists that responded to our questionnaire work in the hospitals that perform the highest percentage of craniotomies per year. These hospitals have more resources (thromboelastrography and massive bleeding protocols), perform preoperative fibrinogen tests more often, and establish acceptable platelet levels for the intervention. Nevertheless, most anaesthesiologists do not follow pre-craniotomy protocols for detecting and treating anaemia, despite the existence of a PBM program. This may be due to the short interval between the pre-anaesthesia consultation and surgery, and to the persistence of traditional, non-evidence-based practices.

Preoperative Hb is the main factor that determines the need for perioperative transfusion6 and is an independent factor for post-surgical morbidity and mortality.5,6 The incidence of anaemia in patients scheduled for craniotomy depends on the population and the type of surgery. Data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in North America show that the incidence of severe to moderate anaemia (haematocrit less than 26% and between 26% and 30%, respectively) in elective cranial surgery patients is 2.7%.7,8 The number of patients with anaemia that undergo cranial surgery in Spain has yet to be determined. According to current evidence,6,8–10 if the interval between the pre-anaesthesia consultation and surgery is long enough, or if anaemia is detected early enough, steps should always be taken to correct iron levels.

The transfusion rate in neurosurgery is low (around 2%), and has been the focus of a number of cost-benefit studies.11 In Spain, a retrospective single-centre study performed between 2008 and 2018 showed that cross-matching and pre-ordering red blood cells that are eventually not used in patients scheduled for tumour craniotomy costs health services $138,585.2.12 In the meta-analysis published by Rail et al.13 risk factors for transfusion in brain tumour surgery were greater age, high anaesthesia risk score (ASA III or IV), and comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease.

The practice of pre-ordering 1–2 bags of red blood cells prior to major neurosurgery is widely reported in the literature,11 and as our survey shows, one that also persists in Spain. The wisdom of this traditional practice has started to be questioned, and experts now recommend only pre-ordering blood on the basis of the patient’s characteristics (high risk)19 and the type of surgery scheduled.14 According to our survey, blood is pre-ordered by the neurosurgery team in 67.1% of cases. In order to pre-order blood in selected patients, it is essential to note the expected blood loss in the surgery request form. According to our survey, only 65.6% of respondents included an estimation of bleeding in the surgical request form, a finding that underlines the importance of effective communication between neurosurgeons and anaesthesiologists.

In the subanalysis of cases in which a member of the neuroanaesthesia team evaluated the patient prior to the intervention, patients were asked specific questions to rule out a coagulation disorder. This directed history-taking is very important, because the patient's clinical and family history can reveal information that would lead the clinician to suspect the presence of hereditary or acquired blood dyscrasia, and a report of spontaneous or injury-related bleeding can lead the clinician to suspect either a mild or serious disorder.15

The management of antiplatelet and anti-inflammatory drugs is still widely debated. All respondents base the interruption of antiplatelet medication on the drug's half-life and the last dose, as indicated in clinical guidelines. Most respondents do not interrupt anti-inflammatory drugs. The preoperative use of NSAIDs has been associated with intracranial bleeding in 1.1% of patients due to their antiplatelet effect.16 Despite this, intraoperative administration of NSAIDs has not been shown to increase the incidence of complications such as post-operative bleeding, kidney failure or ulcers.17,18 In their recent systematic review, Mestdagh et al.19 indicate that NSAIDs should be included in the postoperative analgesic regimen for craniotomy.

Maintaining a perioperative platelets >100,000/µL is standard practice in patients undergoing elective neurosurgical surgery, and this transfusion threshold is also accepted by 76.8% of anaesthesiologists replying to our questionnaire. The same platelet threshold was also applicable to patients previously treated with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), according to 77.8% of respondents. Guidelines on platelet transfusion thresholds in neurosurgery are based on weak clinical evidence and expert opinion. Nevertheless, the recommendation to maintain platelets at >100,000/mL before scheduled neurosurgery is well established and is unlikely to be revised due to the mortality and morbidity associated with an increased risk of bleeding in this patient population.20 Intraoperative platelet transfusion may be useful in non-thrombocytopenic patients being treated for known platelet dysfunction and in patients being treated with clopidogrel or ASA, regardless of platelet count.21

Clinical practice in patients undergoing urgent surgery and taking antiplatelet agents varies considerably. Platelet transfusion has been suggested in patients with ASA- and P2Y12 receptor inhibitor-associated intracranial haemorrhage scheduled for a neurosurgical procedure (conditional recommendation, moderate evidence).22 A retrospective study in 538 patients with nontraumatic intracranial haemorrhage showed that platelet transfusion in patients taking antiplatelet therapy was not associated with worse outcomes after adjusting for haematoma expansion. However, in the unmatched cohort, patients who received platelet transfusions were more likely to deteriorate, undergo surgical intervention during their hospital stay, be discharged with a worse modified Rankin Scale score, or die.23

Although, ideally, the possibility of bleeding should be announced verbally when going through the surgical checklist in all patients, in our survey compliance was around 93.5%. Identifying patients at high risk of bleeding before surgery allows the team to implement multidisciplinary measures, such as preoperative embolization of larger vessels, optimization of Hb levels, non-invasive Hb monitoring (SpHb), cannulation of large vessels, and avoid the lethal triad/pentad (hypothermia, acidosis, coagulopathy, tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion and hyperglycaemia) by administering warmed fluids/blood products and even placing blood in a refrigerator near the operating room.24

During persistent or difficult-to-control bleeding, more than half of all respondents would consider following viscoelastic testing algorithms, which have proven useful in guiding transfusion strategies in trauma patients and in elective major surgery.4 Nevertheless, the usefulness of transcranial cerebral oximetry and tissue oxygen pressure (PtiO2) to guide blood transfusion25 and viscoelastic tests to guide the transfusion of blood products in neurosurgery patients has yet to be confirmed, and there is no definitive evidence that they improve neurological outcomes26

In our survey, 81.3% of respondents used a transfusion threshold of 7−9 g/dL, a figure that appears to be consistent with current evidence. According to Rail et al.,13 an Hb threshold of 8 g/dL may be safe in patients undergoing tumour surgery, and up to 10 g/dL should be considered in patients who may present an intraoperative haemodynamic challenge (symptomatic anaemia, active bleeding, patients with previous cardiovascular disease). In the largest retrospective analysis of brain tumour surgery published so far,27 the authors found no differences in morbidity and mortality between patients assigned to a restrictive (Hb <8 g/dL) and liberal (Hb 8−10 g/dL) transfusion strategy.

Finally, the ideal intraoperative blood pressure is hard to define, and the threshold should be based on each patient’s usual blood pressure levels. Some authors have suggested a new approach involving adjusting mean blood pressure targets on the basis on each patient’s cerebral autoregulation.28 In their review, Iturri et al. individualised optimal arterial pressure levels (mean and systolic) to be maintained perioperatively according to the type of underlying brain pathology (cranial trauma, aneurysm, arteriovenous malformations, tumours), arguing that the differences in their pathophysiological characteristics make it impossible to make general recommendations.29

LimitationsThe limitations of this study include, firstly, the absence of sampling, since the survey was sent via email and posted on social media by SEDAR. Due to the survey method used, the possibility that some respondents completed the questionnaire several times cannot be ruled out, and the method of dissemination could have introduced an element of selection bias, so our sample is not wholly representative of the population of neuroanaesthesiolgists in Spain. However, to our knowledge, this is the first published survey on bleeding in neurosurgery that encompasses the entire perioperative period, and the high volume of participation adds weight to our results. Nevertheless, the survey was conducted using self-administered questionnaires, which may reduce the reproducibility of the study.

Future lines of research could specifically address the use of NSAIDs in the postoperative period, platelet transfusion based on the results of specific tests, and the use of ROTEM to correct preoperative coagulation disorders and to guide the treatment of intraoperative haemorrhage.

ConclusionsPreoperative Hb is not routinely optimised before elective craniotomy, probably due to the short interval between the preoperative assessment and surgery. Despite the low transfusion rate reported in the literature, most respondents routinely pre-order 2 bags of red blood cells, even though this practice is not based on objective criteria or predictive models. The use of viscoelastic testing algorithms to guide transfusion therapy is becoming more widespread. This survey gives insight into standard practice in Spain, and could be a starting point for introducing evidence-based, more cost-effective protocols.

FundingThis study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.