The evolution of blood saving programs to Patient Blood Management (PBM) represents a broader and more comprehensive approach to optimize the use of the patient's own blood, thus improving clinical outcomes and minimizing the risks associated with allogeneic blood transfusion with a holistic view of socio-economic sustainability.

Implementing the strategies of the three PBM pillars in any hospital center involves a transversal change throughout the organization in which it can be very useful to apply the strategy defined by Kotter at the business level for change management.

The support of renowned institutions such as the World Health Organization and the European Commission demonstrates the importance and urgency of implementing PBM programs, setting guidelines at an international level and supporting the adoption of effective strategies in the management of blood transfusion at a national and institutional level.

In Spain, we need to have health managers at both the Hospital Management level and the Regional Health Services and/or Ministry of Health that provide the necessary resources for its proper implementation in the health system from primary care to hospital care and also the resources for the timely evaluation of the results.

La evolución de los programas de ahorro de sangre al Patient Blood Management (PBM) representa un enfoque más amplio y completo para optimizar el uso de la sangre del propio paciente, mejorando así los resultados clínicos y minimizando los riesgos asociados con la transfusión de sangre alogénica con una visión holística de sostenibilidad socio-económica.

Implementar las estrategias de los tres pilares PBM en cualquier centro hospitalario supone un cambio transversal en toda la organización en el que puede ser de gran utilidad aplicar la estrategia definida por Kotter a nivel del mundo empresarial para la gestión del cambio.

El respaldo de instituciones de renombre como la Organización Mundial de la Salud y la Comisión Europea demuestra la importancia y urgencia de implementar programas de PBM, marcando pautas a nivel internacional y respaldando la adopción de estrategias eficaces en el manejo de la transfusión sanguínea a nivel nacional e institucional.

En España, necesitamos contar con gestores sanitarios tanto a nivel Dirección-Gerencia como de las Consejerías y/o Ministerio de Sanidad que proporcionen los recursos necesarios para su adecuada implementación en el sistema sanitario desde la atención primaria hasta la atención hospitalaria y también los recursos para la oportuna evaluación de los resultados.

Since the 1980s, blood saving programs have gradually but significantly been evolving towards Patient Blood Management (PBM),1 a comprehensive strategy that prioritizes patient well-being by optimising the management of their own blood.2,3 This marks a milestone in medicine by shifting the focus from merely reducing and optimising the use of allogeneic transfusions to a holistic, patient-centred approach that includes preoperative haemoglobin optimisation, minimizing blood loss, and maximising the patient’s physiological reserve.4

PBM is based on evidence-based medicine and provides a framework for clinical decision-making and establishing standards of care. Recent studies have shown that it significantly reduces the need for transfusions and their associated risks, and also reduces mortality, postoperative complications, and length of hospital stay, while improving the patient’s quality of life.1,5,6 The adoption of PBM is not only a clinical imperative but also a cost-saving strategy. By reducing the need for blood transfusions, PBM directly reduces the cost of purchasing and administering blood products, performing compatibility tests, and treating adverse reactions and administration errors. It also introduces indirect savings by reducing the incidence of moderate-to-severe complications, infections, and thrombosis,7 and the number of operations that need to be cancelled or rescheduled due to lack of blood components (a growing trend reported worldwide).1

This combination of savings and strong scientific evidence makes PBM a cost-effective, quality-based strategy that is needed now more than ever.4,8 Including PBM in current clinical practice promotes socioeconomic sustainability, improves clinical outcomes and patient safety, and consolidates the paradigm shift towards comprehensive patient blood care.9

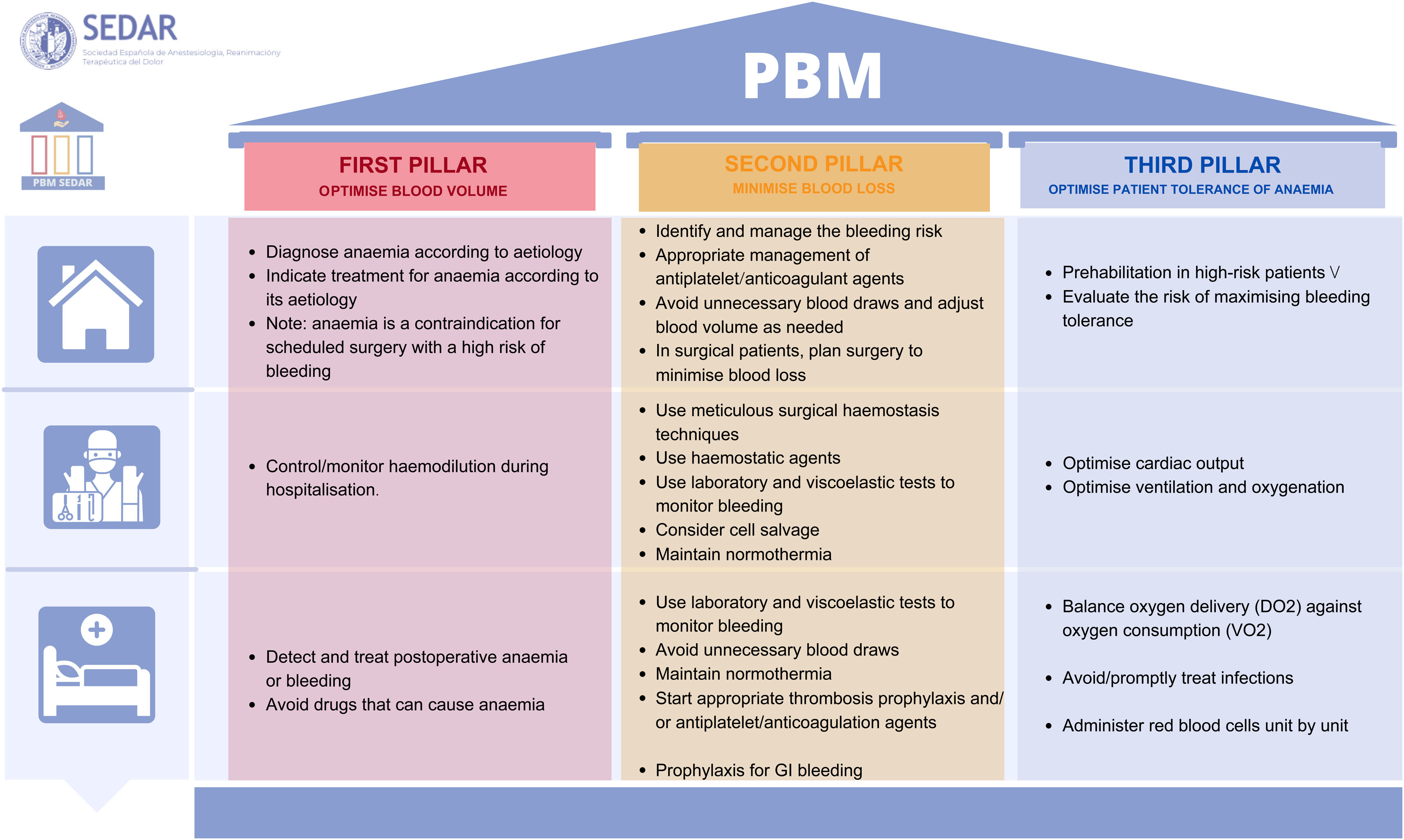

Institutional and expert recommendations regarding the implementation of PBM programsIn 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) called on countries worldwide to establish PBM programs.10 Despite this, implementation has been extremely patchy, and in 2022 the WHO again raised the need to urgently implement PBM11 (Fig. 1).

In 2017, the European Commission published a guidebook to help all EU Health Authorities build national PBM programs, emphasizing the need for national authorities to actively pursue the dissemination and implementation of PBM.12,13

In Spain, given the wide range of indications and uses of transfusion, a panel of experts from 6 scientific societies drew up the “Seville Document” on Alternatives to Allogeneic Blood Transfusion. This consensus document, first published in 2006 and updated in 2013,14 offered a series of GRADE-based recommendations to reduce the transfusion rate.

One of the Do not do recommendations included in the "Commitment to Quality in Scientific Societies in Spain" project promoted by the Spanish Society of Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation and Pain Therapy (SEDAR) was “Do not perform elective surgery in patients with anaemia at risk of bleeding until a diagnostic workup is performed and treatment is given”.15 Similarly, the Spanish Society of Haematology and Haemotherapy (SEHH) does not recommend “transfusing more packed red blood cells than necessary to relieve symptoms of anaemia or to return a patient to a safe range (7–8g/dl in stable non-cardiac patients), or transfusing packed concentrated red blood cells in unstable iron deficiency anaemia”.16 The Spanish Society of Intensive Care Medicine and Coronary Units (SEMICYUC) issued a similar statement recommending against “transfusing packed red blood cells in critically ill, haemodynamically stable, non-bleeding patients with organ dysfunction and with haemoglobin > 7g/dl”.17

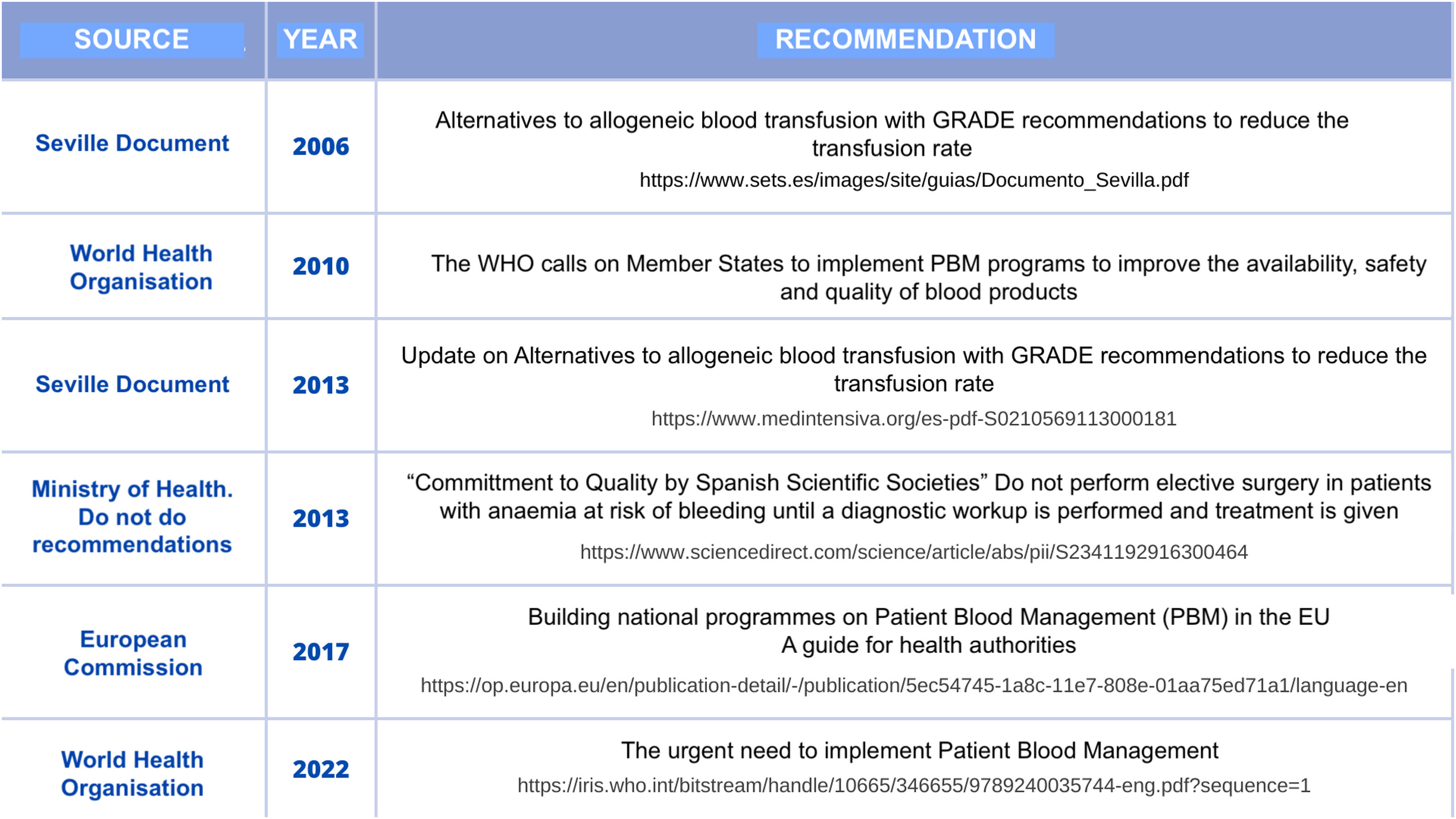

Key aspects of the PBM pillarsPBM programs are based on a combination of measures grouped into 3 pillars: optimise the patient’s own blood volume, minimise blood loss, and optimise the patient’s physiological tolerance of anaemia (avoid unnecessary blood transfusions) (Fig. 2). Although the literature abounds with recommendations on the use of perioperative PBM,18–20 these programs are not exclusive to surgery but can also be used in other departments treating patients with potential blood loss.21,22

In the first pillar, the first step is to diagnose, study, and treat anaemia according to its aetiology, with iron deficiency being the most frequent cause.19,20,23–26 In surgical patients, preoperative anaemia has been shown to increase both complications and perioperative mortality,25,27 and scheduled major surgery should be deferred until haemoglobin levels have been corrected. The risk of thrombosis must be weighed up against the risk of increased bleeding in each patient before discontinuing or replacing antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication and restarting it after the procedure.23,28,29 This information should be given to the patient using language they can easily understand.

In the second pillar, fluid overload should be avoided throughout the perioperative period to avoid haemodilution.18,20,23 It is also necessary to maintain optimal haemostasis (temperature, pH, calcium) to avoid excessive bleeding. Minimally invasive surgical techniques and topical haemostatics should be used when indicated. Likewise, prophylactic tranexamic acid has been shown to reduce bleeding, and is a simple and easily protocolised strategy.18–20,23,26–28

Intra- and postoperative bleeding should be monitored using clinical and laboratory parameters, and haemostasis should be evaluated using viscoelastic tests, if available. All these recommendations should be used judiciously, avoiding unnecessary blood loss.18,20,23,26–28

Postoperative anaemia must be corrected using the most physiological approach possible by compensating for haematinic deficiencies caused by blood loss during surgery and optimising the patient's tolerance to anaemia (improving haemodynamics, oxygenation and managing pain). Restrictive transfusion thresholds should also be used, factoring the patient's clinical tolerance to anaemia and comorbidities into the decision to transfuse. When assessing the need for transfusion, other parameters in addition to haemoglobin levels must be considered (O2 consumption, mixed/central venous O2 saturation, lacticaemia, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, oxygenation, and even, in very specific situations, regional cerebral O2 saturation19,23,25–28,30–32)

In the third pillar, red blood cells should be administered unit by unit, evaluating the effect of the transfusion before deciding to administer the next unit (individualised transfusion).18,23,26–28,30–32

Specific measures that can improve the PBM culture in your hospitalImplementing PBM strategies in any hospital requires cross-cutting organisational changes because, as mentioned above, it involves introducing new procedures in several different specialties and in numerous scenarios. For this reason, the project should be presented to the hospital’s administrators, since their support will be essential to achieve a comprehensive change. It is essential to focus on the following key points8,19,33–35:

- -

Correcting anaemia, reducing bleeding, and avoiding unnecessary transfusions will not only reduce complications, but also improve clinical outcomes. These measures also cut costs and reduce the consumption of blood products, and therefore meet the criteria for a triple-aim project: better patient experience (satisfaction and quality), better clinical outcomes, and lower costs.9,36

- -

These strategies are part of the value-based healthcare framework, which aims to obtain the best, most cost-effective outcomes for both patients and the community while adhering to ethical standards.37

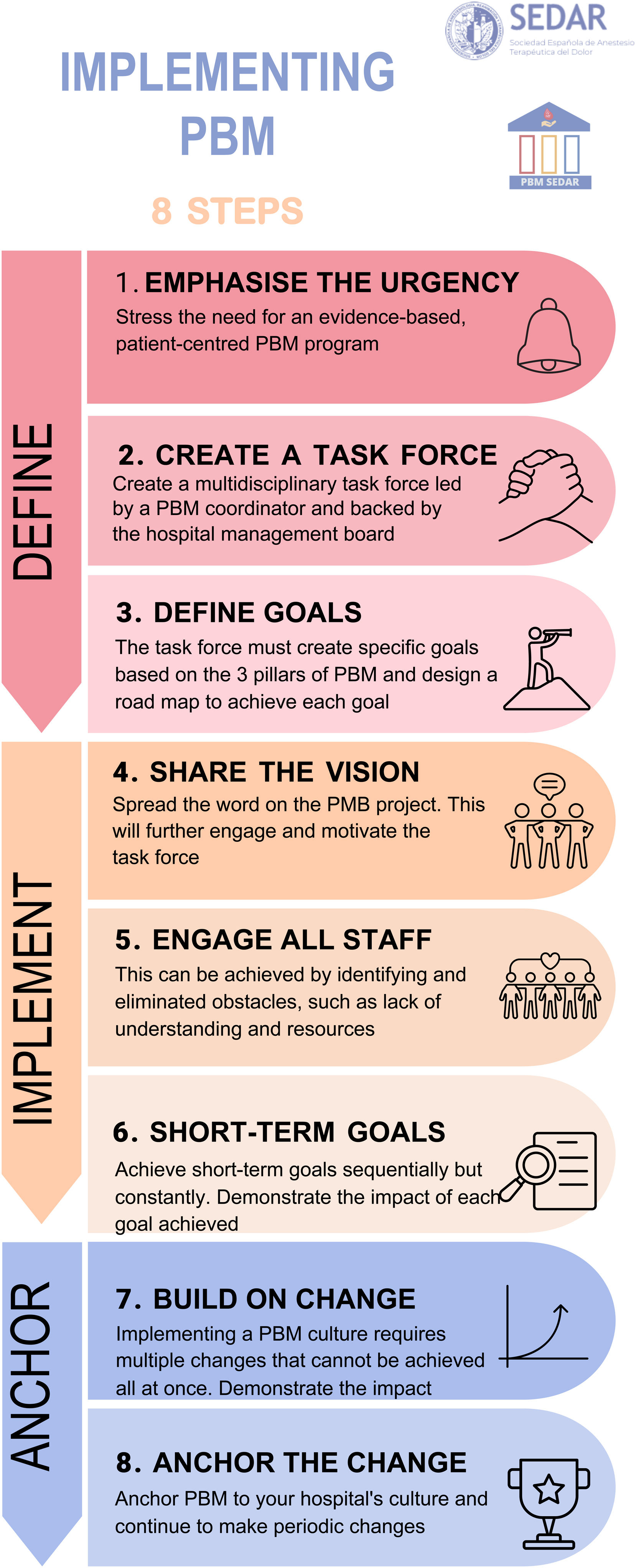

Kotter’s 8-step model for corporate change management can be useful to implement a PBM program.13 We have adapted this model to the healthcare setting, and put forward the following suggestions for implementing PBM in a hospital (Fig. 3).

Emphasize the urgency of establishing an evidence-based, patient-centred PBM programThe first step in implementing PBM in our hospitals is to stress the importance and need for this approach, highlight its benefits, such as lower morbidity and mortality, improved quality of life, and savings in healthcare resources, and detail the positive outcomes achieved by other hospitals that have already adopted PBM.

Create a task forceIt is important to create a PBM task force made up of different specialists (anaesthesiologists, surgeons, haematologist, transfusion specialists, primary care doctors, pharmacists, nurses, etc.). These specialists must form a strong, tightly knit group led by a PBM coordinator supported by the hospital’s administrators.38

Define specific goalsThe task force will need to define specific goals derived from the 3 pillars of PBM and create a roadmap based on the needs, infrastructure and resources (material and human) in each hospital or health centre.19,39

This roadmap could also include continuing training for both health professionals and users, action protocols tailored to the characteristics of each hospital, key performance indicators, and benchmarking and reporting for team members.40

Share the visionAll change projects need to be disseminated both internally and externally, and the key players in this process will be the hospital’s public relations or communications department. Several communication channels are available: multidisciplinary clinical sessions, computer screensavers, posters, social networks, email updates, etc. It is also important to engage patients in the PBM strategy by means of animated educational tools, if possible.41

Engage all staff members and remove obstaclesTwo of the main barriers to implementing PBM are resistance to change - no doubt due to lack of information, and lack of resources.

One strategy is to organise continuing training courses to improve knowledge of PBM strategies. It can also be useful to create and disseminate internal protocols, posters, infographics, pocket or online guidelines, intranet information, checklists, etc., as well as electronic aids (transfusion apps, for example).39,42,43 This material will make it easier for all stakeholders involved to abandon antiquated and possibly unsuitable practices in favour of PBM recommendations.

To tackle the issue of shortage of human and/or material resources, it is important to highlight that the initial investment required to implement a PBM program will pay ample dividends down the line, as reported in many studies.8 Ideally, we should be able to find examples of this in our own hospital. From this point on, we need to specify the real needs identified in the program and maximise these resources.

Create short-term goalsImplementing the PBM culture involves multiple changes. It is unrealistic to think we can make all these changes at once, but we cannot accept half measures. This is why it is so important to define a series of short, medium and long-term goals, and draw up a roadmap to achieve each of them sequentially.42 A specific example is the synergy created by ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) and PBM programs in the framework of perioperative medicine. Various clinical practice guidelines recommend Integrating PBM recommendations into ERAS protocols to improve implementation. One of the first such guidelines to make this recommendation was the Clinical pathway for intensified recovery in adult surgery (RICA, in its Spanish acronym) developed in Spain.44–46

Combining ERAS and PBM will also increase the number of stakeholders, thereby extending dissemination of the program.

Build on changeThis follows on from the foregoing point, insofar as settling for a single goal will not bring about change; several goals should be defined and achieved sequentially. Each goal achieved will reduce the number of potential obstacles, since the change itself will build momentum and create a growing number of loyal, motivated staff members.

Anchor PBM to your hospital’s cultureAs your goals are achieved, the day will come when the switch to PBM is consolidated in your hospital. However, you will have to continue to apply pressure to maintain this paradigm shift. This means moving forward with the task force to ensure that the new strategies introduced continue to be relevant. Hence the importance of creating a coalition and using motivational strategies to ensure long-lasting change.47

Engaging with the public administration to improve implementation of PBM in the health system (primary and secondary care). Experience in SpainHaving understood the advantages48 of PBM, the obligation to implement these programs in both primary and secondary care, and the need for all specialties to adopt one or more of the 3 pillars of PBM, we face the challenge of securing the resources needed to achieve this goal. This brings us to the question of “how”.

The Australian experience 49 has shown that engaging the Australian Government in the project was key to the success of the program. For this reason, several autonomous regions in Spain, such as the Madrid, Navarra and Catalonia, have decided to involve hospital administrators, regional health departments, the Ministry of Health and various scientific societies in their projects.50,51

The approach to implementing PBM programs in Spanish hospitals varies considerably.52 At the management level, implementation depends on the receptivity of hospital administrators. Regarding the Public Administration, establishing contact is difficult or even impossible, so novel and innovative routes must be found. For example, a consultancy firm can act as a go-between to both explain the importance of the PBM project and to obtain the necessary resources for its development.53

One of the first steps is to nominate a PBM coordinator54 in each public hospital. This is an official position, similar to that of a Transplant Coordinator, and is recognised as such by the corresponding regional health authority, thus freeing the nominee from other duties to enable them to lead the project effectively. For example, the PBM Coordinators in the Autonomous Community of Madrid (CAM) have decided to perform a preliminary analysis of the existing PBM infrastructure in the region's public hospitals. This project involves evaluating the resources available in each hospital to establish a comprehensive anaemia optimization consultation that would also treat post-critical and emergency cases. The group aims to design an anaemia consultation model suitable for all hospitals that the CAM regional health authority can then offer to each hospital administrator as the first step towards standardising PBM in all hospitals in the CAM.

Results of implementing PBM programs in SpainIn Spain, various task forces have worked on implementing PBM programs. Their efforts have mainly been focussed on Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology departments. In their report on their experience blood-saving programs, Albinarrete et al. showed that this approach reduced transfusion needs in both hip (47.6% in 2006 and 30.6% in 2011) and knee (33.6% in 2011 and 16.2% in 2011) replacement surgery.55 They also observed a reduction in the average length of stay, although the authors could not definitely attribute this to the blood-saving programs.

Recently, other groups have shown that preoperative haemoglobin ≥ 14g/dl is associated with a lower risk of postoperative complications in patients undergoing primary hip and knee replacement surgery.56 Other groups have studied the effect that improving postoperative anaemia has on transfusion requirements in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery,57 while other have analysed the impact of PBM protocols on transfusion requirements in patients undergoing cardiac58 and gastric cancer surgery.59,60

Another important multicentre, evidence- and value-based initiative has been the development of the Maturity Assessment Model of Patient Blood Management (MAPBM, https://mapbm.org/home/es),40 a program developed by a multidisciplinary group of experts from different fields (anaesthesiology, haematology, health economics, outcomes research, clinical management, and healthcare information systems) that has been introduced in more than 60 hospitals in Spain. The MAPBM program measures and compares various indicators among hospitals to evaluate the degree of implementation of the PBM mainly in surgical scenarios (knee arthroplasty, hip arthroplasty, open and laparoscopic colorectal surgery, cardiac valve surgery, femur fracture, and hysterectomy). The program establishes benchmarks to measure intra- and inter-hospital deployment of PBM53 and PBM support tools, such as an annual report that assesses the degree of maturity using a PBM matrix (Supplementary Material).

In line with the Donabedian framework, the model identifies structure, process and outcomes as the 3 main dimensions that can be graded to measure the progress of a PBM.53 Structure indicators include all the relatively stable material and organizational attributes, as well as available human and financial resources. Process indicators measure perioperative activities included in the 3 pillars of the PBM. The outcome indicators measure healthcare in terms of the transfusion rate, complications, and hospital length of stay (Supplementary Material).

A recent study evaluated the impact of the application of the MAPBM tool on a total of 8080 surgeries (3780 pre-PBM and 4,300 post-PBM). In the pre-PBM cohort, 0.2% of patient received iron to correct anaemia vs 2.7% in the post-PBM. The transfusion rate was 46.7% in the pre-PBM cohort and 37.6% in the post-PBM group. Implementation of PBM was associated with a lower perioperative red blood cell transfusion rate (OR: 0.68 [CI 95%: 0.63−0.75]). Length of hospital stay fell from 13.6 days to 11.6 days after PBM implementation.61 Other studies have revealed suboptimal adherence by hospitals to blood management recommendations in patients undergoing total knee and hip arthroplasty.62 Considerable differences were observed between hospitals in the implementation of PBM protocols. Quality indicators and composite scores could be valuable tools to monitor and compare patient blood management. Reporting and measuring quality of care plays a key role in closing the gap between evidence-based practices and their real-world implementation. The MAPBM is expected to be a useful tool that allows healthcare organizations to not only measure PBM practices, but also to implement these programs and ensure that their protocols comply with PBM recommendations, thereby improving patient safety and outcomes.40

Conclusions and call to actionThere is a pressing need for immediate, effective PBM programs in Spain1 to comply with the 4 Ps of modern medicine: preventive, predictive, personalized, and participatory. It is also essential to adhere to the key pillars of PBM: scientific evidence, equal access, economic efficiency, and ecological sustainability (the 4 Es).

There is evidence that these programs not only significantly improve clinical outcomes, but also optimize the use of healthcare resources and promote a more equitable and sustainable healthcare system.

PBM must be implemented now; it is an urgent need for the present and an unavoidable commitment for the future.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interestAAM has received honoraria from Menarini for conferences outside the scope of this study. MBL has received honoraria from CSL Behring for educational conferences.

EMA, RDA, AMMSP, AP, SAL, IF, MQD, GY, MJC have no conflicts of interest to declare.