The dynamics of the global business environment have led to changes in the skills required by accountants in order to add value for their clients. Consequently, there is a growing pressure on accounting educators to design and implement educational programmes that could contribute to the development of the relevant skills. In such a context, it is possible that some characteristics of students (for example communication apprehension, ambiguity tolerance, or learning styles) could be constraints on both skills development and pedagogical change. Previous studies have reported that accounting students tend to have higher levels of the constraining characteristics than students from other disciplines. However, previous research has not considered the extent to which those characteristics are inter-related or have possible synergistic effects in accounting students. The results of this study, based on a sample of accounting students, indicate that those relationships exist. The patterns of correlations are indicative of the constraints that an accounting educator must overcome to effectively develop certain skills. Implications of the results are discussed.

Las dinámicas del entorno empresarial globalizado ha llevado a cambios en las capacidades necesarias para que los contables puedan añadir valour a sus clientes; lo que ha motivado una presión creciente en los docentes de contabilidad para que diseñen e implementen programas que contribuyan al desarrollo de las competencias clave. En este contexto es posible que alguna de las características de nuestros alumnos actúen como limitadores del cambio pedagógico y del desarrollo de capacidades; como la aprensión comunicativa, la tolerancia a la ambigüedad o determinados estilos de aprendizaje. Los resultados de estudios previos indican que los estudiantes de contabilidad suelen presentar niveles más altos en las características que actúan como limitadores, en comparación con otros estudiantes de áreas afines. En este contexto, una cuestión clave es si estas características están interrelacionadas causando un efecto sinérgico. Los resultados obtenidos con una muestra de estudiantes de contabilidad indican que estas relaciones existen. Los patrones de correlaciones encontrados son indicativos de las limitaciones que un docente de contabilidad afronta para desarrollar las capacidades clave. Las implicaciones de estos resultados se discuten aportando líneas de actuación.

As Jackling and De Lange (2009) highlight, the context and dynamics of the global business environment has resulted in changes in the skills required by accountants in order to add value for their clients. This is a global phenomenon: the same basic skills are considered essential for all graduates: communication, team-working and problem solving (e.g. OECD, 2011; Precision Consultancy, 2007; UKCES, 2009). Also, learning to learn and a commitment to lifelong learning are considered as integral aspects of being a professional in a constantly changing work environment (IFAC, 2010, p. 15).

Employers of accountants and accounting professional bodies have expressed the view that there exists a clear necessity to improve the professional skills of potential, new and established members of the accounting profession. Therefore there is a growing pressure on accounting educators to design and implement educational programmes that could contribute to the development of the relevant competences (Bonk & Smith, 1998; Gammie & Joyce, 2009). Moreover, in the European context the integration of the European Higher Education Area promotes a competence-based system which encourages students to take a much more active role in their own learning and educators to use relevant active pedagogical methods (Arquero & Tejero, 2011). It also adds regulatory pressure for the implementation of the changes (Gonzalez et al., 2014).

It is worrying that professional skills are still not being fully developed despite professional bodies, employers and academic researchers raising concerns for over a quarter of a century. Attempts had been made to develop the skills but they had been ineffective. So, what is preventing the success of the attempts to improve communication skills? An important insight is was given by Stanga and Ladd (1990) and Ruchala and Hill (1994) who stated that despite the importance of professional skills, relatively little was known about the barriers that accounting students and professional accountants face when attempting to develop their professional skills.

In such a context it is possible that some characteristics of students could be constraints on both skills development and pedagogical change: communication apprehension (CA), ambiguity tolerance (AT) or learning styles and preferences (e.g. Arquero & Tejero, 2009; Arquero & Tejero, 2011; Yazici, 2005; Zhang, 2002). This is the case in our area, where previous studies indicated that accounting students tend to (i) present higher levels of those constraining characteristics in comparison with their colleagues from other vocational areas (e.g. Arquero & Tejero, 2009; Lamberton, Fedorowicz, & Roohani, 2005 for ambiguity tolerance or Joyce, Hassall, Arquero, & Donoso, 2006; Ameen et al., 2010 for communication apprehension) or (ii) a combination of learning preferences that could hamper the implementation of pedagogical innovations (e.g. Arquero & Tejero, 2011).

Furthermore, there are studies that reveal some connections between those characteristics (e.g. Bourhis & Stubbs, 1991: communication apprehension-learning preferences; Comadena, 1984, communication apprehension-ambiguity tolerance) and suggest a possible synergistic effect. However, we are not aware of any research paper that studies the relationship of these characteristics in the accounting domain. Importantly Triki, Nicholls, Wegener, Bay, and Cook (2012) suggest that accounting students and accounting education could be essentially different from other types of students and their discipline education, and thus the findings for accounting education could simply be different. Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to analyse the potential relationships between two personality traits (communication apprehension and ambiguity tolerance) and relevant learning styles. The potential implications of the analysis of the results for accounting education will then be discussed.

The structure of the paper is as follows. The second section is a brief literature review of skills requirements in our area and the role of AT, AC and learning styles as potential constraints for skills development. The third section sets out the objectives and research questions, followed by a methodology section where the sample, procedure, instruments and variables used are presented. Finally, the paper draws to a close with the results section followed by a discussion of their implications.

Literature reviewSkills requirementsThere are clear indications that an expectations gap exists between the perceived needs of employers and their perceptions of the employability of graduates (Azevedo, Apfelthaler, & Hurst, 2012). This is the case both in general and specifically in the case of accounting graduates (Jackling & De Lange, 2009; Bui & Porter, 2010). There is a long history of debate concerning the specific profile of skills required to be developed by accounting graduates; starting in the USA (AICPA, 1987, 1988, 1992, 1999; AAA, 1986; Arthur Andersen and Co et al., 1989; AECC, 1990; Albrecht & Sack, 2000) but becoming global (Common Content Project, 2011; IFAC, 1994, 2010; IAESB, 2014; QAA, 2007; UNCTAD, 1998). Central to this debate is the balance between technical accounting and business knowledge, and also personal skills and qualities (Crawford, Helliar, & Monk, 2011). Personal skills such as communication, teamwork, time management and problem solving enable technical accounting content to be exercised in the relevant context and are necessary to achieve competences (IFAC, 2010). However, there is a consensus between employers and academics that the required personal skills and qualities are in many instances not being exhibited (Jackling & De Lange, 2009). A further concern is the ability of students to adapt and develop the required skills given the current pedagogy. Consequently a different approach from both academics and students may be needed. The traditional approach, which tends to focus on intellectual skills framed by the required technical knowledge, may need to be broadened to incorporate a specific focus on the application of knowledge and thereby enabling the development of problem solving abilities. Furthermore, this needs to be combined with the development of wider vocational skills consistent with the changing business environment in which accountants now operate (Jones, 2010; Wells, Gerbic, Kranenburg, & Bygrave, 2009).

Various reports and academic research on the changes required to meet the needs of employers have identified several key areas:

- •

Intellectual skills (problem solving and decision making)

- •

Technical and functional skills (mainly technical content)

- •

Personal skills (including ability to adapt to change and lifelong learning)

- •

Interpersonal and communication skills (work with others, integrate in teams and communicate effectively)

- •

Organisational and business management skills

These skills are similar to those stipulated by IFAC (2010) and IAESB (2014) as being necessary requisites in a programme of professional accounting education (IES3).

Although a set of these skills (personal, intellectual and interpersonal) and a high level of technical expertise are needed to be successful in the workplace (Wells et al., 2009) there seems to be a higher importance placed on communications skills. For example, Jackling and De Lange (2009) asked accounting graduates to nominate the most important skills for progression. Communication was ranked first, followed by problem solving, with technical skills ranking fifth. Similarly, the practitioners in the study by Crawford et al. (2011) thought that all listed skills (based on QAA, 2007 statement) were important, but a ranking of their importance showed that analytical skills, presentation skills and written communication skills were the most important. The same study asked which generic skills students should gain at university and which skills employers believed should be prioritised. The same three skills (analytical, oral and written communication) were identified as the top three. This does not just apply to big firms; employers from medium and small firms emphasised the importance of communication skills (Bui & Porter, 2010).

The above recent results are consistent with earlier literature (for instance, Ingram & Frazier, 1980; Novin, Pearson, & Senge, 1990; Novin & Tucker; 1993 in the USA) and are recognised throughout the world, for example Diamond (2005) in the USA, Hassall, Joyce, Arquero, and Donoso (2005) and Arquero et al. (2001, 2007) in a European context, Kavanagh and Drennan (2008), De Lange, Jackling, and Gut (2006) from an Australian perspective and Gray (2010) and Gray and Murray (2011) from New Zealand.

An interesting argument by Jones (2010) emphasise that generic skills are organic interconnected networks rather than discrete skills. In other words she notes that it is very difficult to disentangle meaningfully critical-thinking from problem-solving, from analysis and from the communication of those ideas. Therefore, as Jones (2010) points to necessary identification of the potential barriers to the teaching of generic attributes there seems to be a reason to examine these interconnected barriers with an emphasis on the key attribute of communication.

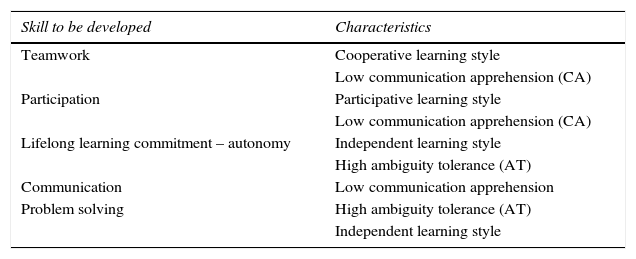

ConstraintsThere is a clear demand for accounting educators to focus on the development of professional skills in the development of future accountants. Past attempts had been relatively unsuccessful in remedying this perceived need. The question that needs to be addressed is what might be preventing the success of the attempts to improve communication skills. In this context, certain characteristics (see Table 1) could act as constraints for both skills development and pedagogical change.

Characteristics needed to develop skills.

| Skill to be developed | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Teamwork | Cooperative learning style |

| Low communication apprehension (CA) | |

| Participation | Participative learning style |

| Low communication apprehension (CA) | |

| Lifelong learning commitment – autonomy | Independent learning style |

| High ambiguity tolerance (AT) | |

| Communication | Low communication apprehension |

| Problem solving | High ambiguity tolerance (AT) |

| Independent learning style |

Communication apprehension (CA) was defined by McCroskey (1984: 78) as “an individual's level of fear and anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person”. Consequently CA and may form a barrier that stops the development of students’ communication skills. Anxiety can in many instances prevent successful performance and over time may form a barrier to future performance and development (Hassall, Arquero, Joyce, & Gonzalez, 2013). Accordingly, high CA is generally associated with low communication performance (e.g. Byrne, Flood, & Shanahan, 2012; Daly et al., 1997; O’Mara, Allen, Long, & Judd, 1996). More recently, Marshall and Varnon (2009) reported this negative relationship amongst accounting majors.

CA is not only associated with low communication performance. As evidenced by Spitzberg and Cupach (1984) and Allen and Bourhis (1996), techniques aimed at the development of communication skills will not resolve CA and if an individual has a high level of CA the techniques may be ineffective and consequently improved communication performance will not occur. Marshall and Varnon (2009) highlighted that a greater insistence of participation in “standard” communication training serves to validate the fears of high CA accounting students and therefore not only fails to improve communication skills, but negatively affects communication performance.

A cause of concern for accounting educators is the evidence that accounting students tend to have higher levels of CA than students from other vocational areas. This observation has been a constant finding originating in the early studies made in the USA (e.g. Stanga & Ladd, 1990; Simons, Higgins, & Lowe, 1995) and continuing through to the more recent research developed in other countries: UK and Spain (Hassall, Joyce, Ottewill, Arquero, & Donoso, 2000; Arquero, Donoso, Hassall, & Joyce, 2007), Ireland (Byrne, Flood, & Shanahan, 2009), New Zealand (Gardner, Milne, Stringer, & Whiting, 2005) and Canada (Aly & Islam, 2003). Furthermore, Joyce et al. (2006) and Ameen et al. (2010) provide evidence that students who have chosen to join accounting courses have above average levels of CA. This suggests that there is a mismatch between the students’ perceptions of what skills they require and those that will be needed in their chosen vocational area.

Ambiguity tolerance“Ambiguity” is the perceived absence of the information that is needed to understand a situation and to make choices with predictable outcomes (Arquero & Tejero, 2009). In a situation that demands evaluation or choice, the perceived presence of ambiguity is threatening and presents a cognitive challenge in the form of desired but absent or inaccessible information. Consequently, ambiguity could be a barrier that hampers decision making and prediction (McLain, 2009). Intolerance of ambiguity is the aversion to this lack of information, whereas ambiguity tolerance (AT) is the degree of acceptance of, or even attraction to, this lack of information (Arquero & Mclain 2010).

The relevance of ambiguity (and AT) in accounting was pointed out by Harding and Ren (2007): accounting is inherently related to judgement, which could itself be described as decision making in the face of ambiguity. In this line, the last revision of the IES 3 (IAESB, 2014) highlights the importance of ambiguity in defining the level of proficiency for accounting students.

A review of the literature (Arquero & Tejero, 2009) of the impact of ambiguity tolerance on problem solving and decision making highlighted that AT is a key trait. High AT students perform better than their peers with low AT in complex scenarios (e.g. Ebeling & Spear, 1980; Yurtsever, 2001). Low AT individuals not only have a lower performance (Banning, 2003) they also present lower levels of confidence in the decisions they made (e.g. Gul, 1986; Ghosh & Ray, 1997), tend to perceive higher levels of risk (e.g. Tsui, 1993; Wright & Davidson, 2000), underscore positive performance evidence (Liedtka, Church, & Ray, 2008) or focus on unfavourable outcomes (Lowe & Reckers, 1997). At an organisational level these differences could ultimately affect the performance (Westerberg, Singh, & Hackner, 1997) and the ability of an organisation to adapt to change (Judge, Thoreson, Pucik, & Welbourne, 1999; Walker, Armenakis, & Bernerth, 2007).

Again there is a mismatch: the profiles of accounting students do not match the characteristics of those needed to manage unexpected, ambiguous situations and problems. Amernic and Beechy (1984) drawing on work by Holland (1973) and Amernic et al. (1979) point out that, in general terms, the profiles of accounting professionals and students are of a ‘conventional type’. Holland (1973) describes ‘conventional type’ individuals as being characterised by their preference for activities that entail ordered and systematic manipulation of quantitative data and by an aversion to ambiguous, exploratory or unsystematic activities. Wang and Chan (1995) indicate that the preference for quantitative data by low AT individuals could be explained in the following terms: reducing a complex situation to hard (quantitative) data may lead AT individuals to perceive the problem or environment as less ambiguous than it really is.

Research indicates that this is a global phenomenon. Irrespective of their country of origin, accounting students tend to have lower levels of ambiguity tolerance than other students (Arquero & Tejero, 2009; Lamberton et al., 2005) and also have lower levels when compared to their respective national norms (e.g. Elias, 1999).

Learning stylesAmong the most publicised objectives of the Bologna process the Ministerio de Educación highlights the new pedagogic approach that “could transform our educational system based on teaching into one based on learning”. This change requires three prerequisites (MEC, 2005):

- -

Higher autonomy and involvement of students in their learning process.

- -

The use of active pedagogical methods including team work.

- -

The role of the teaching staff as a manager of challenging learning environments.

As Arquero and Tejero (2011) noted, students are supposed to have a higher level of independence and responsibility to design their own curriculum and to obtain the maximum benefit from the resources and activities at their disposal, but in order to make the best use of those resources, students should be able to be active participants, to be independent learners and to collaborate with other students by working in teams.

Commitment to lifelong learning and problem solving skills, key skills stressed in employability reports and specifically in accounting statements, require students to be independent learners. Teamwork is another key skill for employability that requires current students (future professionals) to be collaborative learners.

Unfortunately, recent results (Arquero & Tejero, 2011) show that accounting students, when compared to students on other social sciences degrees, are less independent and more dependent. This provides a warning that accounting students will experience more difficulties when working and learning in an autonomous way than other students. A further concern is that whilst students from other disciplines tend to score higher in ‘participant style’ as they become older, accounting students tend to develop lower scores. Accounting students in contrast to other students (see also Grasha, 1996) felt less comfortable collaborating with their peers in projects, groups discussions etc., as they became older.

Connections between characteristicsIf the results reviewed above are a cause of concern when studied in isolation, this concern grows when connections between the characteristics are studied. These connections could be explained though Curry's Onion Model (1983). Individual difference constructs could be place in a layered model (Sadler-Smith, 2001) where the core consists of the central personality dimensions (more stable) passing outward to more context-dependent and less fixed constructs (cognitive style, learning style, learning preferences). As Duff, Dobie, and Guo (2008) highlight, the learning behaviour is fundamentally controlled by the central personality dimensions. Therefore, stable traits such as CA and AT (Inner personality dimensions) affect, along with contextual factors, the learning styles and preferences.

Some research papers have studied relationships between these personal characteristics. An early study by McCroskey, Daly, and Sorensen (1976) found correlation between CA levels and intolerance of ambiguity levels. Comadena (1984) investigated the relationship between CA and performance in brainstorming groups and found that individuals with low levels of CA were more likely to be high producers of ideas, perceive the act of brainstorming more positively, and demonstrate higher ambiguity tolerance than those amongst their peers who had high CA. Specifically focusing on accounting students, Elias (1999) reported higher levels of CA and lower levels of AT in accounting students in comparison with other students and national norms.

Regarding learning styles, Opt and Loffredo (2000) found correlations between differences in Myers-Briggs personality type preferences and CA levels. Russ (2012) highlights a consistent finding across studies investigating the relationship between CA and learning mode preferences: students with low CA demonstrate a preference for the active experimentation learning mode (Bourhis & Berquist, 1990; Dwyer, 1998; Johnson, 2003). This finding suggests that students who feel comfortable communicating in various contexts prefer learning by doing (in line with the active pedagogy proposed to develop competencies), whereas students with high CA demonstrate a preference for the reflective observation learning mode (Dwyer, 1998; Russ, 2012).

Allen et al. (1987) found negative correlations between CA and independent and collaborative styles. Bourhis and Stubbs (1991) found a significant relationship among levels of CA and learning style (CA was correlated positively with an avoidant style and negatively with independent, collaborative and participant styles). Allen, Long, O’Mara, and Judd (2007) again found similar patterns of correlations when reporting significant negative relationships between CA and independent and collaborative styles.

Dobos (1996) analysed the relationship between CA and affective responses to collaborative learning. The main finding of the analysis was that individuals with low CA associated collaborative learning with above-average communication satisfaction, greater participation activity, higher fulfilment of expectations, and below average anxiety.

Purpose and research questionsThe preceding review identifies a perceived gap in the development of, among others, communication, problem solving and teamwork skills. Universities are under pressure from stakeholders and institutional contexts (González, Arquero, & Hassall, 2014) to change their pedagogy to a more active one whereby students are more autonomous and involved in their own learning process. However certain personal characteristics of the students could act as constraints for both the skills development and the pedagogical change. Relevant literature highlighted that students in the accounting area tend to present inadequate profiles in some of these relevant characteristics (e.g. higher levels of CA and lower levels of AT) and that the characteristics could be inter-related. Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to analyse the potential relationships between two relevant personality traits in this context: communication apprehension and ambiguity tolerance and relevant learning styles. This objective leads to the following research questions

RQ1: Are there significant relationship between the personality traits and learning styles?

RQ1a: Is there a significant relationship between CA and learning styles?

RQ1b: Is there a significant relationship between AT and learning styles?

RQ2: Are there significant relationship between the personality traits (CA and AT)?

MethodologySample and procedureFor convenience the sample of students used for this study were all drawn from undergraduate courses in accounting at the Sheffield Hallam University. A total of 300 students (all the students enrolled on these courses) participated. The questionnaires were distributed during class time. Although participation was voluntary, no students refused to complete the questionnaire. Therefore the impact of non-response can be ignored. A member of the research team gave a brief presentation of the project, highlighting the importance of sincere answers, assuring the confidentiality of the data gathered and that the data would be only used in an aggregated way and for research purposes only. The questionnaires included statements telling respondents that there were no right or wrong answers.

Approximately 69% of the sample was female. The ages of the students ranged from 20 to 28 years, with an average age of 22.5 years and a standard deviation of 0.99 years.

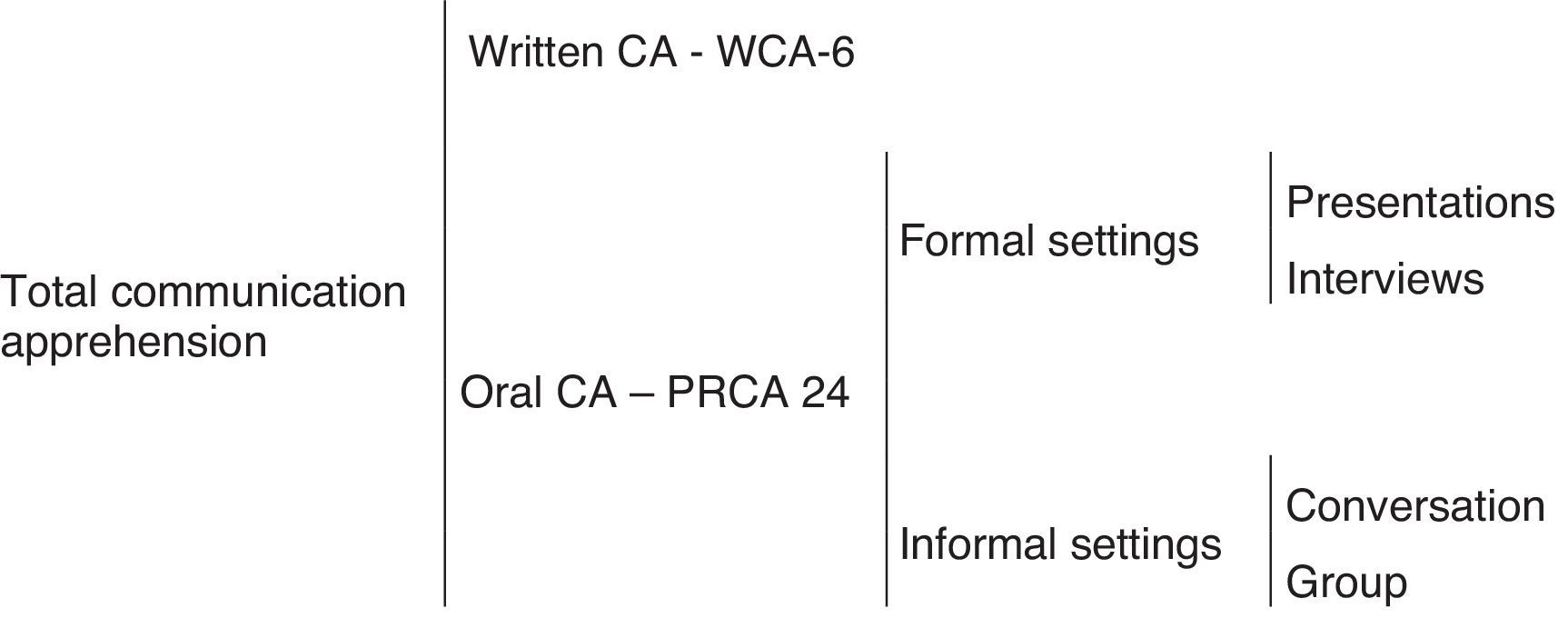

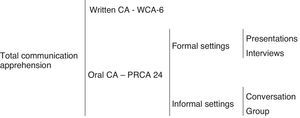

Instruments1Communication apprehensionAn instrument consisting of two questionnaires were completed by each student to measure CA (Fig. 1). The first questionnaire is the adaptation by Hassall et al. (2000) of the Personal Report of Communication Apprehension (PRCA-24) developed by McCroskey (1984, 2006) to measure oral communication apprehension. The PRCA-24 consist of 24 items about communication in four contexts: formal settings (represented and explained as interview and presentation situations), and informal settings (represented and explained as conversation and group discussion situations). The only modifications introduced by Hassall et al. (2000) from the original instrument were two word changes: “interview” in place of “meetings”, and the “presentations” in place of “public speaking”. This adaptation has been used in several research papers (e.g. Arquero et al., 2007; Gardner et al., 2005; Joyce et al., 2006), reporting a robust and reliable set of results for the instrument. Further information on psychometric characteristics of the original PRCA-24 can be found in Leary (1991).

To measure written communication apprehension the instrument used is the WCA-6 (Arquero et al., 2012). The WCA-6 is a reduced version (6 items) of the WCA-24 (Hassall et al., 2000) an adaptation to university students of the Writing Apprehension Test (WAT, Daly & Miller, 1975). As Shanahan (2011) highlights, the original WAT questionnaire was more appropriate to English composition programmes and therefore, Hassall et al. (2000) altered some of the wording (e.g. “composition” was changed to “essays” or “written work”), removed four statements and inserted two new ones.

The statements in both questionnaires are to be answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”) and a higher score indicates higher level of CA.

Ambiguity toleranceFrom the first conceptualization of the trait called intolerance of ambiguity by Frenkel-Brunswik around the end of the 1940s, various authors (e.g., Bhushan & Amal, 1986; Budner, 1962; Kischkel, 1984; McDonald, 1970; Rydell & Rosen, 1966) followed her conceptual definition in order to develop instruments to measure it (Arquero & Mclain, 2010). However, despite the continued interest in AT the reliability and validity of the most frequently used measures is poor (v.g. Furnham, 1994; Kirton, 1981; Lange and Houran, 1999; Ray, 1988) and some of these measures lack a theoretical structure that is consistent with information theory, especially with regard to the nature of ambiguity and information (see Furnham & Ribchester, 1995).

To overcome the psychometric shortages of many of these instruments, McLain (1993) developed the Multiple Stimulus Types Ambiguity Tolerance scale (a 22-item instrument) and later proposed a shorter version (MSTAT II; McLain, 2009) that kept adequate standards of reliability and validity. The shorter version can be used in conjunction with other instruments without causing cognitive fatigue (Arquero & Mclain, 2010).

In this study the MSTAT II was used without further modifications. This instrument consists of 13 statements covering the range of ambiguous situations proposed by Budner (1962) (insoluble stimuli, novel stimuli, complex stimuli items, uncertain stimuli, generally ambiguous stimuli) to be rated on a Likert-type format with 5 alternatives, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score indicates higher level of ambiguity tolerance.

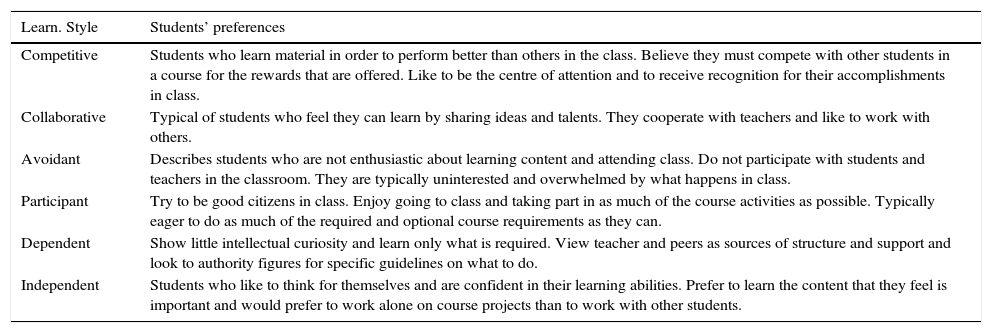

Learning stylesFrom the wide range of learning styles questionnaires available (see Cassidy (2004) for a review and classification) the only one that allowed relevant preferences to be captured (collaborative, dependent-independent, etc. styles) was the Grasha-Reichmann Student Learning Style Scale (Grasha, 1996).2 This inventory consists of 60 items (10 per style), to be answered on a 5 points Likert scale (ranging from 1 for total disagreement to 5 for total agreement, with 3 being the neutral opinion). The opinions captured provide measures on six scales (Table 2) that according to Cassidy (2004) focus on learning preferences and incorporate the belief that style is, to some degree, fluid and will alter according to the learning context. A higher score in each of the measures obtained indicates a higher preference for this style.

GRLSS Learning styles and students’ preferences.

| Learn. Style | Students’ preferences |

|---|---|

| Competitive | Students who learn material in order to perform better than others in the class. Believe they must compete with other students in a course for the rewards that are offered. Like to be the centre of attention and to receive recognition for their accomplishments in class. |

| Collaborative | Typical of students who feel they can learn by sharing ideas and talents. They cooperate with teachers and like to work with others. |

| Avoidant | Describes students who are not enthusiastic about learning content and attending class. Do not participate with students and teachers in the classroom. They are typically uninterested and overwhelmed by what happens in class. |

| Participant | Try to be good citizens in class. Enjoy going to class and taking part in as much of the course activities as possible. Typically eager to do as much of the required and optional course requirements as they can. |

| Dependent | Show little intellectual curiosity and learn only what is required. View teacher and peers as sources of structure and support and look to authority figures for specific guidelines on what to do. |

| Independent | Students who like to think for themselves and are confident in their learning abilities. Prefer to learn the content that they feel is important and would prefer to work alone on course projects than to work with other students. |

In accordance with Grasha (1996), with the exception of the participant-avoidant scale which presents very high negative correlation coefficients, these measures should not be seen as bipolar dimensions.

The relevance of this instrument can be derived from the view that in order for pedagogical changes to be successful it is necessary for students to become participative, collaborative and to some extent, independent. In contrast, highly dependent, avoidant, or highly competitive students do not present the necessary attitudes for the required pedagogical changes to work properly. Also, to develop lifelong learning skills students are required to present a ‘low dependent’ profile, and team working requires a high collaborative style.

Composite measuresIn order to make results easier to interpret Kusurkar, Ten Cate, Vos, Westers, and Croiset (2013) obtained and used in their paper the composite variables good study strategy (that summarised the scores obtained for approaches to study, also used in Arquero, Fernández-Polvillo, Hassall, & Joyce, 2015) and quality of motivation (that condensed the self-determination measures into one score). For the same purposes, Kizilgunes, Tekkaya, and Sungur (2009) also defined a composite measure of learning approaches. In a similar way, two composite measures were calculated here: good learning style (GLS) was calculated by adding the scores obtained in independent, participant and collaborative styles and subtracting the scores for dependent and avoidant styles. Also, a global CA score (GCA) was calculated as the addition of the OCA and WCA scores (both OCA and WCA were re-expressed in the same scale in order to have the same weight in the resulting variable).

ResultsReliabilityPrevious studies provide evidence of acceptable reliability for CA and AT scales in English language samples. Hassall, Arquero, Joyce, and Gonzalez (2013) report Cronbach's values for the same CA scales used in this paper ranging from 0.73 for the WCA-6 to 0.85 for the presentation scale. For AT scale, McLain (2009) reports internal reliability (Cronbach's α) over 0.80.

The published evidence on the reliability of the GRLSS scales is less clear. The internal reliability measures provided by Yazici (2005) for a sample of higher education students in business-related subjects ranged from 0.73 to 0.89. However, Ferrari et al. (1996) indicated that the Participative, Avoidant, and Collaborative scales showed acceptable internal consistency, but the Dependent, Independent, and Competitive scales did not (both studies using Cronbachs’ alpha).

Despite its widespread use, there are critical voices on the use of Cronbach's alpha: Raykov states that is in general a mis-estimator of scale reliability at the population level (Raykov, 2001; Raykov, 2004), and Shevlin, Miles, Davies, and Walker (2000) highlight that it is influenced by factors other than the reliability of the items that comprise a scale. Therefore, in this study we are using an alternative measure: the composite reliability (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Our data provided composite reliability scores ranging from 0.83 (WCA-6) to 0.91 (conversation) for CA scales and 0.78 for AT, with all of them above the cut-off point of 0.7. However, three scales included in the GRLSS gave composite reliability scores around 0.6: avoidant, participative and collaborative.

In order to solve this problem, item-factor loadings were examined. Four items for each scale (those with lowest item-factor loadings) were discarded.3 The resulting scales presented the following composite reliability scores: dependent, 0.82; competitive, 0.81; collaborative, 0.75; independent, 0.73; participant, 0.71 and avoidant, 0.67. The reliability of the avoidant scale can be considered low if used for individual diagnosis purposes, but it is acceptable for group level, educational studies (Kizilgunes et al., 2009).

A complementary cross factor loading analysis indicated that no item presented higher loadings in other scales than in its own construct.

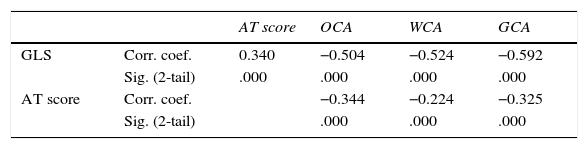

Relationships at a global levelThe analysis of the correlations between the composite variables allows obtaining a global view of the relationships (see Table 3).

Students presenting characteristics that could be labelled as ‘good learning styles’ tend to present lower scores in communication apprehension at a global level (correlation GLS-GCA, −0.59, p<1%) and in any of the main communication contexts (writing: correlation GLS-NWCA, −0.52, p<1% and oral contexts: correlation GLS-OCA, −0.504, p<1%), and are more tolerant to ambiguity (correlation GLS-AT, 0.34, p<1%). Therefore, at an aggregated level, the answers to RQ1a and RQ1b are, yes: both inner personality traits seem to have a significant relationship with learning preferences strengthening desirable (low CA, high AT→high GLS) or constraining (high CA, low AT→high GLS) profiles.

The second research questions focused on the relationships between traits. The results indicate that ambiguity tolerance and communication apprehension are inter-related (all the correlations are negative and significant at 1% level) mainly due to oral CA (correlation: −0.344, p<1%). However, although weaker, the relationship WCA–AT (−.224, p<1%) is also significant.

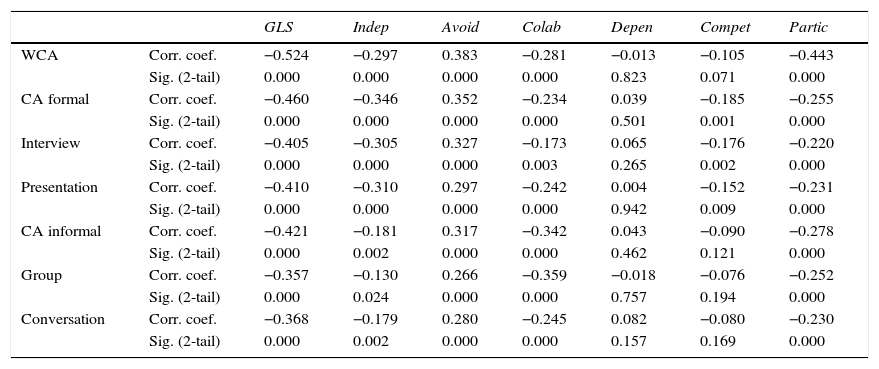

RQ1a: Relationships learning styles – CAAnalysing in more detail the relationships between the different learning styles and the CA subscales, a pattern that is consistent with previous research findings arises. All CA constructs (oral and written) present significant negative correlations with independent, collaborative and participant styles of learning and positive correlations with the avoidant style (Table 4).

Correlations (Pearson): CA and learning styles.

| GLS | Indep | Avoid | Colab | Depen | Compet | Partic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WCA | Corr. coef. | −0.524 | −0.297 | 0.383 | −0.281 | −0.013 | −0.105 | −0.443 |

| Sig. (2-tail) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.823 | 0.071 | 0.000 | |

| CA formal | Corr. coef. | −0.460 | −0.346 | 0.352 | −0.234 | 0.039 | −0.185 | −0.255 |

| Sig. (2-tail) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.501 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| Interview | Corr. coef. | −0.405 | −0.305 | 0.327 | −0.173 | 0.065 | −0.176 | −0.220 |

| Sig. (2-tail) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.265 | 0.002 | 0.000 | |

| Presentation | Corr. coef. | −0.410 | −0.310 | 0.297 | −0.242 | 0.004 | −0.152 | −0.231 |

| Sig. (2-tail) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.942 | 0.009 | 0.000 | |

| CA informal | Corr. coef. | −0.421 | −0.181 | 0.317 | −0.342 | 0.043 | −0.090 | −0.278 |

| Sig. (2-tail) | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.462 | 0.121 | 0.000 | |

| Group | Corr. coef. | −0.357 | −0.130 | 0.266 | −0.359 | −0.018 | −0.076 | −0.252 |

| Sig. (2-tail) | 0.000 | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.757 | 0.194 | 0.000 | |

| Conversation | Corr. coef. | −0.368 | −0.179 | 0.280 | −0.245 | 0.082 | −0.080 | −0.230 |

| Sig. (2-tail) | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.157 | 0.169 | 0.000 |

It should be noted that the largest positive coefficients correspond to the relationship between avoidant and oral CA in formal contexts and avoidant and writing CA. This means that individuals with high CA in writing and oral communication in formal contexts tend to adopt an avoidant learning style. Contrariwise, all CA measures are negatively correlated with participant style (the largest negative coefficient corresponds to the relationship between participant style and writing CA) and collaborative style.

The negative correlation between the collaborative style of learning and CA in informal contexts (mainly group CA) is consistent with the characteristics of collaborative students who have a preference for working with others in small groups and feel they can learn by sharing ideas and abilities (Arquero & Tejero, 2011).

Therefore, as an answer to RQ1, CA appears to have an influence in key learning styles: high CA seems to be associated with an avoidant style and also negatively affects independence, participation and collaboration of students in the learning process. Only dependent style, as defined in the GRLSS, seems to be not related to CA.

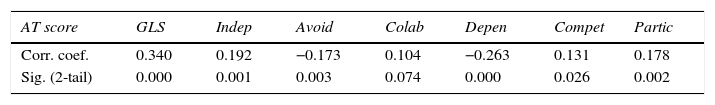

RQ1b: Relationships learning styles – ATA detailed analysis of the relationships between AT and learning preferences indicated that all the correlations are significant although AT is more strongly related to dependent/independent styles (Table 5). Students with high AT tend to be more independent and less dependent than their low AT colleagues. This influence of AT is consistent with the definition of such styles. Dependent students show little intellectual curiosity and learn only what is required for the prevalent task. They look to authority figures for specific guidelines on what to do, and view teachers and peers as sources of structure and support. Conversely independent students like to think for themselves, are confident in their learning abilities and like a maximum amount of choice and flexibility and a minimum of structure and form in their learning environment (Arquero & Tejero, 2011).

Another significant correlations appear between AT and learning styles: negative with avoidant style (−0.173, p<1%) and positive with participant (0.178, p<1%) and competitive (0.131, p<5%).

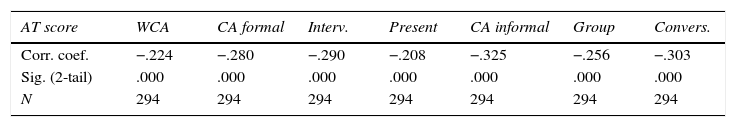

RQ2: Relationships AT and CAResults presented in Table 6 show that there is a significant negative correlation between AT and all CA constructs. This is consistent with previous studies using other instrument to measure AT (e.g. Elias, 1999 using McDonald's AT20).

The stronger relationships appear between AT and CA in informal settings and is mainly due to the responses to the situations involving “conversation”. The more formal CA subscales (e.g. writing CA and presentation) appear to be less strongly connected to AT although the stronger correlation in formal situations is “interview”. It seems that conversations and interview settings are perceived as allowing opportunities for unexpected ambiguous situations that need immediate responses to arise.

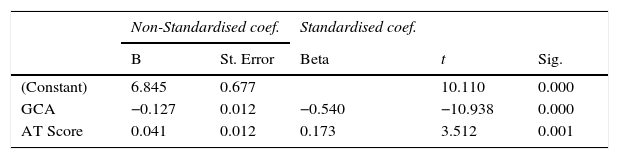

Complementary analysis: linear regressionGiven the relationships between the three groups of key variables a complementary regression analysis was performed. Following the argument of Duff et al. (2008), learning behaviour (the dependent variable in the model) is controlled by the central personality dimensions AT and CA (independent variables in the model).

The results (Table 7) suggest that both AC and AT have a significant influence on learning preferences. As expected, the effect of AC in GLS is negative, higher levels of apprehension result in lower scores in good learning style (standardised coefficient=−0.54; P<1%) and the effect of AT is positive, higher scores in ambiguity tolerance result in higher scores in GLS, although weaker than the former (standardised coefficient=0.17; P<1%).

DiscussionIt is clear that pressure is being exerted by the needs of employers and the educational changes being promoted in European universities for greater emphasis to be placed on the development of skills. Knowledge and technical ability must be supported by communication, interpersonal and problem solving skills, and the abilities to adapt to change and self-learn if students are to be equipped to enter the work place.

Specifically in accounting, in all relevant stakeholders statements from the Bedford Report (AAA, 1986) to the last revision of the IES3 (IAESB, 2014), there has been an acceptance that accounting courses should aim to develop the students’ capacities for analysis, synthesis, problem solving and communication. This has subsequently been interpreted as indicating that students should actively participate in their learning. Concern has also been expressed that contrary to the real world context in which accountants operate, accounting problems are presented to students as being well structured and well defined (Sterling, 1980; Mayer-Sommer, 1990). In this line, Albrecht and Sack (2000) note a reluctance to use creative types of learning such as team work, case analysis and oral presentations. Their specific recommendation was “it is time that we in accounting education, move away from our reliance on lecture and move towards teaching approaches that convey critical knowledge, skills and abilities” (p.64) This instruction specified cases that would teach dealing with uncertainty and analytical skills, oral and written communication assignments, some elements of group work to teach leadership and working together, and role play to teach negotiation.

However, many students (particularly accounting students) possess characteristics that suggest it would be difficult for them to develop such skills. Previous studies indicate that accounting students have higher levels of communication apprehension, lower levels of ambiguity tolerance, are more dependent and more avoidant than their colleagues studying other disciplines. Individually, each one of these characteristics is a cause for concern. A major concern is if there are associations between the characteristics; such inter-relationships could confirm and consolidate the problems. If there are associations between the characteristics the problems could grow.

These connections could be supported through Curry's Onion Model (1983), AT and CA are stable personality traits (inner personality dimensions) that affect, along with contextual factors, the learning styles and preferences. In this line, the objective of this paper was to investigate to what extent there are associations between characteristics such as CA, learning styles and ambiguity tolerance.

Our results show that these relationships exist. High CA students tend to be less independent, more avoidant, less collaborative and less participant. AT appears to be negatively correlated with CA and dependent style. All of these are characteristics that are associated with constraints for the inclusion of active pedagogy and, analysed in conjunction with reported profiles of accounting students in these relevant characteristics, suggest that some accounting students tend to fail in more than one at the same time. These results are indicative of the tough constraints that an accounting educator could face when trying to effectively develop desired skills with certain students.

Recently Craig and McKinney (2010) reported positive results in a programme of writing skills development, and Rae and Sands (2013) by managing classroom layout increased the amount of one-to-one communication between the tutors and the students, eventually breaking down the communication barriers caused by student apprehension. Also Fortin and Legault (2010) indicated a perceived improvement in skills development by using a mixed teaching approach. More focused on AT, Banning (2003) reported improvements on AT levels by using the case method with management students. However, as a matter of concern, Triki et al. (2012) found that AT and external locus of control appear to be negatively connected with performance suggesting a lack of alignment between the reward mechanism for student performance and the profession's stated competences.

These results, among others support a first line of action: implementing methodologies that could help developing such skills and reduce CA and AT. Given the results by Triki et al. (2012) an institutional commitment to skills development in a coordinated (along all courses and subjects) and coherent (objectives – methodology – assessment system) manner; creating (Byrne et al., 2012) a non-threatening, supportive classroom environment is needed.

However, it is necessary to take into account that for highly apprehensive individuals (higher levels of CA and lower levels of AT) anxiety forms a barrier that impedes development (Hassall et al., 2013a). In this line, the results of Marshall and Varnon (2009) indicated that methodologies that could help low CA students to develop communications skills negatively affect the communication performance of high CA students. Traits are assumed to be more invariable and to play a dominant role in the determination of behaviour, including learning, (Boekaerts, 2000, p. 416) and therefore some methodologies that reported good results will not succeed if used with those highly apprehensive students.

Daly and McCroskey (1975) highlighted the significant relationship between ambiguity tolerance, communication apprehension and the perceived desirability of certain professions. They stated that individuals with higher than average levels of CA or low levels of AT can be attracted towards vocations and professions that they perceive as needing relatively low levels of communication skills or where problems are not complex. There is research evidence that suggests that accounting is in certain instances being chosen as a career because it is perceived as having a low need for communication skills or is being seen as technical and routine. Also research has identified the high prevalence of conventional type (systematic, neat, low AT) in accounting professionals and students. In this line, Byrne and Willis (2005) reported that secondary school students perceived accounting as boring, definite, precise and compliance driven. Also, Bui and Porter (2010) point to the students’ perceptions of accountants, accounting work, and accounting courses as a contributor to the skills gap; and recent findings by Sin, Reid, and Jones (2012) show great variations in students’ awareness of the functional and human aspects of accounting work, ranging from seeing accounting work as being predominantly technical and routine to having a keen awareness of the more complex aspects of contemporary accounting work including its ethical aspects. Thus, at least for some students a mental picture exists of what a ‘stereotypical accountant’ is and the types of tasks they perform as a professional, fostered in some extent by the image exhibited in adverts (Baldvinsdottir, Burns, Nørreklit, & Scapens, 2009), films (Beard, 1994) or even jokes (Bougen, 1994) that clearly diverge from the professional profile needed to succeed in the 21st century. Such perceptions associated to the stereotypical accountant may discourage bright, creative students from pursuing accounting degrees (Cory, 1992) and joining the profession (Saemann & Crooker, 1999).

These results point to the second line of action: relevant stakeholders must make efforts to better explain the tasks a professional accountant must perform and the skills required for a successful career to the relevant audiences (pre-university students, career advisors, counsellors, parents, etc.). Thereby future students could become aware of what it is expected from them in their professional career before enrolling or majoring in accounting degrees. In this line, Cernusca and Balaciu (2015) highlight that professional bodies have a crucial role in permanently contributing to the improvement of the image of the accounting profession. The role of first courses in accounting is also key in this line of action (e.g. Geiger & Ogilby, 2000; Jackling, 2002; Mladenovic, 2000 or Saemann & Crooker, 1999) at least by not reinforcing negative stereotypes and fostering a closer relationship between the learning process and “real” practice (e.g. via placements: Paisey & Paisey, 2010; Wells et al., 2009 or work-based learning: Falconer & Pettigrew, 2003).

Some authors suggest a third line of action (in our opinion to be applied in the short-term and in addition to the other two actions): actively looking for students with the desired profile and filtering at entry level those students that present characteristics that are thought to constrain the development of the desired skills. Correspondingly, Triki et al. (2012) point to the active recruitment efforts and results in Bui and Porter (2010) which raise the negative role of entry criteria (imposed by universities) that permit students with insufficient ability to enrol on accounting programmes.

Any efforts to change the image of accounting will probably take several years to establish the revised view with vocational decision makers and their influencers. The accounting profession needs to make all possible efforts to promote this change in image. In the short and medium term further research needs to be focused on how accounting educators can encourage change in current students in the areas of communication apprehension and ambiguity tolerance to promote specific learning styles and facilitate the implementation and success of appropriate pedagogy.

Limitations and future developmentsResults have been obtained from one UK University. Therefore, in order to obtain more generalisable results data from other Universities and countries is needed.

Given the possible link between preconceptions about accounting and accountants work (accounting stereotypes), students profiles (in terms of CA, AT and styles) and the decision of pursuing an accounting career, a future line of research is to focus on entry level students in accounting and alternative (e.g. business) degrees to examine whether there is a self selection bias due to misconceptions about accounting tasks and skills requirements.

Another future line of research could focus on the relationship between the studied factors and the academic progression of students, not only in terms of performance but also in terms of dropout. A longitudinal study, focusing on more complex subjects, could give insight in this aspect.

FundingProject partly financed by SEJ 130 research group (PAIDI, Junta de Andalucía).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to acknowledge the helpful comments received in the International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation and in the BAFA Accounting Education SIG Annual Conference.

No modifications were introduced in any questionnaire for the present study from the original referenced instruments. All instruments are available on request from the authors and from the original sources.

Contrariwise to, for instance, ambiguity tolerance inventories, which measure the same construct; learning styles inventories focus on very different aspects of the learning, cognitive, study, etc. processes. In accounting education research, Students Approaches to Learning framework (and related inventories, such as SPQ, ASSIST, RASI, etc. measuring deep – surface and achieving approaches) has been widely used. Kolb's experiential learning theory (and related inventories, that measure preferences in terms of experiencing, reflecting, thinking, and acting) also has predicament in our area, but the aspects measured by these, and other, inventories do not allow measuring some characteristics that are relevant for the present study.

Resulting scales are composed as follows. Independent: items 07, 19, 25, 31, 37, 55; avoidant: items 08, 26, 32, 38, 44, 50; collaborative: items 03, 09, 21, 39, 51, 57; dependent: items 04, 16, 22, 34, 52, 58; competitive: items 05, 11, 17, 29, 41, 47 and participant: items 12, 18, 30, 42, 48, 60.