The business model concept is a common topic investigated in different fields of research. To participate to the debate around such concept in the accounting field, the objective of this paper is showing whether and how the voluntary disclosure of the non-mandatory IASB (2010) macro-components, that we consider the key elements of a business model of financial entities, increases the value relevance of accounting amounts. Analyzing a sample of 124 European financial entities over the period 2010–2013, the paper shows that the value relevance of accounting amounts of entities that provide a wide disclosure of their business model is higher than the one of entities that provide a limited disclosure of their business model. These findings not only shed lights about the importance of disclosing information relating to the business model to improve the usefulness of accounting amounts for investors’ strategies, but also have implication for regulators and standard setters that from results could learn the opportunity to make the disclosure of IASB (2010) compulsory for all the IAS/IFRS compliant entities.

El concepto de modelo de negocio es un tema de estudio frecuente en distintos campos de la investigación. Para participar en el debate en torno a dicho concepto en el ámbito de la contabilidad, el objetivo del presente artículo es mostrar si es posible y cómo la divulgación de los macrocomponentes no obligatorios de la IASB (2010), que consideramos elementos clave de un modelo de negocio para las entidades financieras, aumenta el valor de relevancia de las cantidades contables. Por medio del análisis de una muestra de 124 entidades financieras europeas en el periodo 2010-2013, el estudio muestra que la importancia al valor de las cantidades contables de las entidades que divulgan ampliamente su modelo de negocio es mayor que el de las entidades con una divulgación limitada de su modelo de negocio. Estos hallazgos no solo arrojan luz sobre la importancia de transmitir información relacionada con el modelo de negocio de cara a una mejora de la utilidad de los valores contables para las estrategias de los inversores, sino que tiene una implicación para los supervisores y organismos de normalización que podrían, a tenor de estos resultados, aprovechar la oportunidad de convertir la divulgación de la IASB (2010) en obligatoria para todas las entidades que cumplan con las normas IAS/IFRS.

In the last decade, the expression business model (BM) has been studied by so many scholars in both management and accounting studies that its concept cannot be grounded either in economics or in business studies (Teece, 2010). In addition to scholars, also several institutions, including international standard setters (e.g., the IASB and the FASB), national regulators (e.g., the UK Financial Reporting Council) and professional membership organizations (e.g. ICAEW) have manifested their research interests in the BM concept. Initially, the term was used with reference to the e-business context (Timmers, 1998) then it has been extended to all industries (Afuah & Tucci, 2001; Yip, 2004; Osterwalder, Pigneur, & Tucci, 2005; Shafer, Smith, & Linder, 2005; Richardson, 2008). Recently, the concept of the BM has begun to be applied also in the accounting field (ICAEW, 2010).

Motivated by Leisenring, Linsmeier, Schipper, and Trott (2012) and Brougham (2012, p. 345), according to whom “the use of the business model […] provides the most relevant information to users of the accounts”, the main objective of this paper is testing whether and how in financial entities, the disclosure in annual reports of the business model enhances the value relevance of accounting amounts. In the accounting literature (Barth, Beaver, & Landsman, 2001, p. 77), accounting amounts are value relevant if they are associated with stock prices, and value relevance research assesses how well accounting amounts reflect information used by investors (Mechelli & Cimini, 2014, p. 62).

According to our theoretical framework, the macro-components of the business model of financial entities are the five elements that the non-mandatory IASB (2010) “Management Commentary A framework for presentation” requires to disclose in § 24. They regard the nature of the business; the management's objectives and strategies for meeting those objectives; the entity's most significant resources, risks and relationships; the description of the results of operations and prospects; the critical performance measures and indicators that management uses to evaluate the entity's performance against stated objectives.

Despite the objective of IASB (2010) is to assist management in preparing useful management commentary that relates to financial statements prepared in accordance with IFRS (IASB, 2010, § 1), we focus on information disclosed in annual reports for twofold. First, because from Bravo (2016, p. 125) we learn that the annual report has been traditionally considered to be an influential source of information for investors (Lang & Lundholm, 1993; Marston & Shrives, 1991), highly correlated with other financial communications (Lang & Lundholm, 1993). Second because, collecting data, we found the common disclosure practice to include management commentary within the annual report and never in a separate document. Instead, our interest for financial entities is due to a peculiarity of such industry. Financial entities have to respect the capital agreements signed in Basel. In the regulation that introduced the rules of the third accord, we found that two of the five macro-components that the non-mandatory IASB (2010) requires to disclose (the risk and the critical performance measures) identify and should be coherent with the business model of financial entities. We learn this from the Capital Requirements Directive 2013/36/EU (hereby, CRD) and from the Capital Requirements Regulation 575/2013 (hereby, CRR) that introduced in the EU law the Basel III standards adopted by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.

The analysis of the literature and of the recent regulatory framework leads us to hypothesize that the voluntary disclosure of the five core-elements that the non-mandatory IASB (2010) requires to disclose increases the value relevance of accounting amounts.

To test this hypothesis, we analyze the annual reports of European financial entities that comply with the IASB standards and issued their consolidated accounts over the period 2010–2013. Methodologically, we use a price model (Ohlson, 1995) to assess the value relevance of accounting amounts. Results confirm our hypothesis. The value relevance of accounting amounts of entities that extensively disclosure their BM, complying with IASB (2010), is higher than the one of entities that provided a limited disclosure of their BM. We find these results both at an aggregate level, investigating the joint effect that the disclosure of all the macro-components of IASB (2010) has on the value relevance of accounting amounts, and at disaggregate level, that is, investigating separately the effect on the value relevance of the single variables that the non-mandatory IASB (2010) requires to disclose.

This paper contributes to the accounting literature because it provides the evidence that the voluntary disclosure of the macro-components of IASB (2010) makes accounting amounts more value relevant and so increases their usefulness for investors to predict the value of the firm. The contribution of the paper is also due to the evidence that each macro-component contributes in different manner to enhance the value relevance of accounting amounts.

Our results are of interest not only for researcher, but also for practitioners and standard setters. On the one hand, they highlight the importance of disclosing information relating to BM in order to improve the usefulness of accounting amounts. In this regard, the highest value relevance of accounting amounts of entities complying with the practice statement should give evidence on the opportunity to make such disclosure mandatory for all firms that are IFRSs compliant.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section “Literature review and hypothesis development” reviews the literature on the topics investigated and describes our research hypothesis. Section “Sample selection and research methodology” provides details about our sample selection strategy and our research design. The following Section “Empirical findings” presents our research results, while Section “Conclusion remarks” concludes the paper and contains a discussion of the implications, limitations and possible future developments of the study.

Literature review and hypothesis developmentIn this section, we reference the literature that helps us to formulate a research hypothesis about the desirable effects of the voluntary disclosure of the macro-components of IASB (2010) – that we consider elements of financial entities’ business model – on the value relevance of accounting amounts. To do so, first, we will show the reasons why, in financial entities, the macro-components of IASB (2010) could be considered the core elements of a business model. Second, we will focus on the relationship between voluntary disclosure of such macro-components and the value relevance of accounting amounts. Finally, to develop our research hypothesis, we will investigate the reasons why the voluntary disclosure of the business model's elements should enhance the value relevance of accounting amounts.

In the management and accounting literature, the debate around the elements that describe a business model of a company is still open. In this paper, we assume the five macro-components of IASB (2010) enough to identify the business model of financial entities, being perfectly aware that also other elements, not covered by IASB (2010), could be useful to describe a business model.

The first macro-component required by IASB (2010) is a description of the nature of the business that, according to the Management Commentary practice statement, is useful to gain an understanding of the entity and of the external environment in which it operates (IASB, 2010, p. 12). In order to comply with such disclosure requirements, the narrative report should include several information that scholars and practitioners consider within the business model concept. These elements are the sector, the main markets and competitive position (ICAEW, 2010, p. 10), legal, regulatory and macro-economic environments (Chesbrough, 2003; Mitchell & Bruckner Coles, 2004; Chesbrough, 2006; Onetti, Zucchella, Jones, & McDougall-Covin, 2012), main products, services and distribution channels (Osterwalder, 2004), structure and how entity create value1 (Linder & Cantrell, 2001; Chesbrough, 2003; Morris, Schindehutte, & Allen, 2005; Shafer et al., 2005; Chesbrough, 2006; Lambert, 2008; Zott & Amit, 2008; Beattie & Smith, 2013; Nielsen, Fox, & Roslender, 2015). In this sense, in the accounting field, Cinquini & Tenucci (2011, p. 44) argue that, even if in the practice statement there is not a clear reference to the concept of BM, it is implied by the above mentioned aspect of the nature of the business.

Moving to the information regarding the objectives and strategies – the second macro-component of IASB (2010) – in the literature there is an open debate about their connection with BM. According to the large majority of scholars (Hamel, 2000; Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, 2002; Shafer et al., 2005; Zott & Amit, 2008), strategy is a core element of business model. Other scholars highlight that BM and strategy are different concepts and that strategy cannot be included between BM components (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2002; Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010).

After the nature of the business and the objective and strategies, the IASB (2010) asks entities to provide information about their resources, risks and relationships.

For resources, in the management field, we found that they are one of the four pillars, together with customer logic, strategy and network, which according to Hamel (2000) identifies a BM. Later, both Lambert (2008) and Richardson (2008) recognize a crucial role to resources in the value creation process that is a part of the nature of the business previously discussed. More recently, Onetti et al. (2012) argue that different BMs could be identified according to how resources are allocated to different activities the company is focused on and according to the relevance of such activities. Actually, they added (Onetti et al., 2012, p. 360) the primary BM decision refers to the broadness of the activities the company carries out.

For risk, this element has very strict relations with the BM between the elements of the third macro-components, especially in financial entities. To understand the motivations, we can look at the CRD and CRR that introduced in the EU law the Basel III standards adopted by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Introducing in their articles an explicit reference to the BMs of financial entities, the new banking regulation introduces the concept that different risk profiles are useful to identify different BMs. In particular, article 74 of CRD states that a strict relation between the risk-taking process and the BM of the entity exists. The article continues explaining that the governance arrangements (e.g., that include a clear organizational structure with well- defined, transparent and consistent lines of responsibility, effective processes to identify, manage, monitor and report the risks) shall be comprehensive and proportionate to the nature, scale and complexity of the risks inherent in the BM and the institution's activities. The same Directive, in article 76, requires that a risk committee shall review whether prices of liabilities and assets offered to clients take fully into account the institution's BM and risk strategy. Where prices do not properly reflect risks in accordance with the BM and risk strategy, the risk committee shall present a remedy plan to the management body. To strengthen our arguments that different risk profiles are useful to identify different BMs, we can also quote a document issued in 2013 by the financial stability board (hereby FSB) that aimed to facilitate the implementation of the Directive. In this document, the FSB asks to the single national regulators to issue a proper discipline about the risk appetite framework (hereby RAF). In accordance with the requirements of the Directive, the RAF should be institution-specific and should reflect its BM and organization, as well as to enable financial institutions to adapt to the changing economic and regulatory environment in order to manage new types of risk (FSB, 2013, p. 1). Not only in the regulatory framework, but also in the literature we can find evidence that the risk profile of the entities could provide useful information of the BM. In this regard, analyzing the European banking system, Ayadi, Arbak, & Pieter De Groen (2012) identify four different kinds of BMs (i.e., investment banks, retail-focused banks, retail-diversified banks, wholesale banks) that are different from each other depending on several characteristics. Among them, the different risk profile differentiates the various models. In particular, the scholars argue that banks that rely more on non-stable forms of funding and risky investments, such as wholesale and investment banks, tend to face greater estimated default risks and lower liquidity. The focused retail banks face comparable default risks, although these risks appear to be well shielded by relatively strong capital levels and limited liquidity mismatch risks, at least on average. The diversified retail banking model does well under most measures, with low default risks, an average level of capitalization and moderate liquidity risks (Ayadi et al., 2012, p. 29).

As to relationships, according to ICAEW (2010, p.10), the nature of relationships (ICAEW, 2010, p. 10) is one of the elements that more than other characterize a BM. Also the management literature (e.g., Hamel, 2000; Shafer et al., 2005; Mason & Spring, 2011) considers network connectedness a core element of the BM or, as Onetti et al. (2012, p. 359) argue, a comprehensive BM definition should include the networks of relationships with partners. We can add that, in the extent of which the increase of connectedness provides benefits to entities in terms of sharing and reducing the risk (Battiston, Gatti, Gallegati, Greenwald, & Stiglitz, 2012), the process of value creation is facilitated, compared with entities that decide to remain in a periphery not so much integrated with the core of the network (Cimini, 2015).

The last two macro- components that the IASB (2010) requires to disclose are the results and prospects and the critical performance measures and indicators. For results and prospects, entities should explain investors its achievements and its targets, including a clear description of the entity's financial and non-financial performance (IASB, 2010, p. 14). In this regard, Cinquini and Tenucci (2011, p. 53) explain that a BM should help in understanding how the important non-financial and financial variables are related to each other. In the literature, several scholars (Linder & Cantrell, 2001; Petrovic, Kittl, & Teksten, 2001) consider revenue model, that is how revenues are generated, a core element of a BM or one of its building blocks (Osterwalder, 2004). Analyzing financial entities, Van Ewijk and Arnold (2014) looking for the determinants of interest margins in the US commercial banking sector find a significant, positive relationship between a bank's business model, measured using a multi-dimensional proxy of relationship banking activity, and net interest margins. Also the European Banking Authority (EBA, 2014) consider data taken from the balance sheet and from profit and loss, including trends, useful for a business model analysis.

For performance measures and indicators, according to the practice statement, they should be measures that reflect the industry in which the entity operates (IASB, 2010, p. 15). Like risk, both the regulatory framework and the literature allow distinguishing different BMs. In the CRD, article 76 states that the BM determines the firm performance and that in determining the adequacy of the leverage ratio of institutions […], competent authorities shall take into account the BM of those institutions. In the literature, the aforementioned work of Zott and Amit (2008) finds that the BM is a determinant of the performance of the entity, measured by the market value. With specific reference to financial entities, also according to Ayadi et al. (2012), the BM is a determinant of the performance of the entity. In financial entities, indicators are those that reflect the industry in which the entity operates. Actually, according to the CRR and the CRD, financial entities calculate several indicators (ratios) that provide information about the capital adequacy of the entity. These indicators, for instance, control for the minimum prudential requirements, liquidity coverage ratio and net stable funding ratio and according to EBA (2014, p. 32) should reflect the institution's size, complexity, business model and risk profile and should cover geographies, sectors and markets where the institution operates.

Assumed the macro-components of non-mandatory IASB (2010) the key elements of a business model, we reference the literature about the relationship between voluntary disclosure and value relevance and we try to understand the reasons why investors place more weight on accounting amounts disclosed by entities that voluntary disclose information required by IASB (2010).

To do so, we quote those scholars (e.g., An, Davey, & Eggleton, 2011; Shehata, 2014; Motokawa, 2015) that ground voluntary disclosure in the positive accounting theory and in particular in agency theory, signaling theory and legitimacy theory.

For the agency theory, people within the firm act according to their self-interest (Watts & Zimmerman, 1978). The agency theory of Jensen and Meckling (1976) assumes the presence of such conflicting behaviors and theorizes a conflict between shareholders and managers. Voluntary disclosure, on the one hand, should reduce the agency costs due to information asymmetries between shareholders and managers (Motokawa, 2015). These costs, according to Johansson and Malmstrom (2013) lower thanks to the disclosure of information concerning the BM. Voluntary disclosure, on the other hand, should convince the external users that managers are acting in an optimal way (Watson, Shrives, & Marston, 2002). Both these effects make outsiders more confident in accounting amounts disclosed in annual reports that, thanks to voluntary disclosure, should increase their value relevance.

For signaling theory, since the Spence's (1973) seminal work on labor markets, the literature considers the voluntary disclosure of information useful to show to show that the company is better than the other companies in the market. According to Hussainey and Aal-Eisa (2009, p. 452), voluntary disclosure is an important mechanism for signaling future (positive) earnings for decline earnings growth firms. Instead, according to Verrecchia (1990), signals are fundamental to attract new investments and to enhance a favorable reputation. Always according to the work of Johansson and Malmstrom (2013, p. 243) mentioned above, BM information transparency acts as a signal as a powerful tool for convincing external providers of funds to finance the business. Instead, according to Mishra and Zachary (2015, p. 259), the entrepreneur may provide information about the resources (one of the macro-components of a BM) embedded in the entrepreneurial competence to signal their ability and quality to potential investors and strategic partners. Therefore, entities that use signals (e.g., voluntary disclosure) to attract new investments should be those that disclose accounting numbers of higher quality (e.g., more value relevant) compared with entities that do not use voluntary disclosure. Entities that use signals are those where funds are provided by outside shareholders (Nobes & Parker, 2010). Entities that do not need the use of signals are those where funds are provided by families, banks or governments that, acting as insider shareholders, can obtain direct information with limited or no need for public disclosure (Ali & Hwang, 2000, p. 4).

For legitimacy theory, it is centered on the notion of a contract or agreement between an enterprise and its constituents (Shocker & Sethi, 1974) and it is based on the premise that companies signal their legitimacy by disclosing certain information in the annual report (Watson et al., 2002, pp. 292–293). About this theory, we can read in Shehata (2014, p. 20) that company has no right to exist unless its values are being perceived as matching with that of the society at large where it operates (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975; Lindblom, 1994; Magness, 2006). With particular reference to the voluntary disclosure of BM, according to Snihur and Zott (2013) firms can strategically design (and advertise) the content, structure, and governance of their new BMs to selectively increase legitimacy with customers. Therefore, being legitimacy a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions (Suchman, 1995, p. 574), investors that have such perception – also thanks to voluntary disclosure of BM – should have more confidence with accounting amounts, that should be more value relevant compared with those disclosed by entities that are not legitimated by outsiders.

A few last remarks that go beyond the three disclosure theories described above and that convince us that the voluntary disclosure of the BM positively affects the value relevance of accounting amounts. Both the standard setter and scholars explain why the BM disclosure has such capability.

The IASB (2010) provides insights about the usefulness of information that it requires to disclose. For instance, entities that decide to voluntarily comply with this document have to disclose information useful to forecast future cash flows (e.g., §§ 9, 11, 15, 17, 18, 27, 35 and 36), to assess risks (e.g., §§ 18 and 31) the strategies to manage it (e.g., §§ 14a and 32), to appreciate tangible and intangible resources (e.g., §§ 10, 14b and 30). In many paragraphs (e.g., § 24) the document emphasizes its role as an instrument to “better understand” entity characteristics (such as the nature of business, entity's strategies, risks and resources) that are important when using accounting amounts to have information in order to asses firm value.

In the literature, several theoretical papers explain why disclosing the BM could be useful and allow investors to predict future earnings and cash flow.

Leisenring et al. (2012) state that BM accounting provides the most relevant information, because it “determines how value (that is, cash flows) will be realized from the item, and relevance is defined with reference to assessing those cash flows”. Brougham (2012) explained that “the use of the business model […] provides the most relevant information to users of the accounts”. To understand the reasons of these desirable effects, we recall that firms that voluntary disclose the BM information (to reduce information asymmetries, to provide signals to market and/or to legitimate itself), enrich the information environment2 of Collins and Kothari (1989, p. 145). It includes information available for investors to predict the future value of the firm that are able to affect positively the value relevance of accounting amounts. We can also recall that value relevance research are implemented with different models, most of which are derived from the Ohlson valuation model (Ohlson, 1995), that expresses the firm value (Pt) as a function of both earnings (xt) and book value (yt) and other information not yet reflected in accounting amounts (vt). Investors need such information that help them to better understand accounting amounts increasing their value relevance, particularly information useful to make reasonable belief about the persistence of earnings, the risks entities will face in the future, strategies entities have to counterbalance them, and so on. In other words, these information that are not required by any mandatory GAAP, in the extent of which are voluntary disclosed should increase the value relevance of accounting numbers because they increase the ability of investors in using them into valuation formulas because they allow making reasonable beliefs about parameters that affect firm value.

Therefore, assuming the macro-components of the non-mandatory IASB (2010) the core elements of a BM and that voluntary disclosure of the BM make accounting amounts more useful for investors to predict the firm value our research hypothesis is the following:H1 The voluntary disclosure of the core elements of the BM, identified by IASB (2010), makes accounting amounts more value relevant than those reported by entities that provide a limited disclosure of such elements.

The sample analyzed to verify our research hypothesis includes 124 financial entities that comply with the IASB standards and issue their consolidated accounts over the period 2010–2013 (496 firms-year observations). Our interest for financial entities is justified by the fact that in financial institutions some of the elements that the IASB (2010) requires to disclose (e.g., risk, critical performance measures) are archetypal of their BM in the light of the recent regulatory framework (e.g., CRD, RAF).

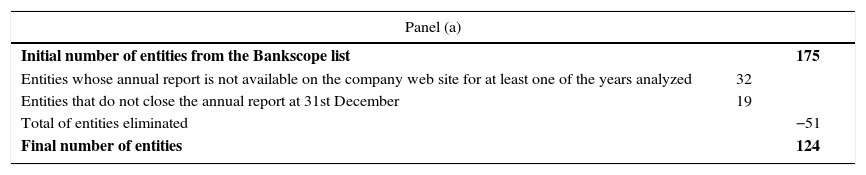

Entities included in the sample are listed in the 15 European countries belonging to the EU at the time of issuance of the Regulation 1606/2002 that introduced the IAS/IFRS in the European countries. Moving from an initial sample of 175 financial institutions, we exclude 51 entities arriving to our final sample of 124 entities. The following table summarizes our sample selection strategy (Table 1, Panel a) and their geographical distribution (Table 1, Panel b).

Sample selection strategy and geographical distribution of the entity analyzed.

| Panel (a) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Initial number of entities from the Bankscope list | 175 | |

| Entities whose annual report is not available on the company web site for at least one of the years analyzed | 32 | |

| Entities that do not close the annual report at 31st December | 19 | |

| Total of entities eliminated | −51 | |

| Final number of entities | 124 | |

| Panel (b) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Entities | Firm-year obs | Percent | Country | Entities | Firm-year obs | Percent |

| Austria | 7 | 28 | 5.7% | Ireland | 1 | 4 | 0.8% |

| Belgium | 3 | 12 | 2.4% | Luxemburg | 4 | 16 | 3.2% |

| Denmark | 7 | 28 | 5.7% | Netherland | 5 | 20 | 4.0% |

| Finland | 6 | 24 | 4.8% | Portugal | 5 | 20 | 4.0% |

| France | 13 | 52 | 10.5% | Spain | 7 | 28 | 5.7% |

| Germany | 13 | 52 | 10.5% | Sweden | 6 | 24 | 4.8% |

| Greece | 5 | 20 | 4.0% | United Kingdom | 18 | 72 | 14.5% |

| Italy | 24 | 96 | 19.4% | Total | 124 | 496 | 100% |

Table 1 (Panel a) suggests that we eliminated entities whose annual report was not available on the company web site in at least one of the years analyzed (n=32) in order to have the same number of observations over the period 2010–2013. In addition, coherently with several other research (e.g. Tsalavoutas, André, & Evans, 2012), we eliminated those whose fiscal year did not end at 31st December (n=19) in order to have accounting amounts, market data and disclosure practices at the same reporting date. Table 1 (Panel b) suggests that more than half of entities (54.9%) come from four countries: Italy (19.4%), UK (14.5%), Germany (10.5%) and France (10.5%).

MethodologyTo test our research hypothesis that the voluntary disclosure of the core elements of a BM positively affects the value relevance of accounting amounts, we follow a protocol with 3 steps.

First, we download from the Bankscope database an excel sheet with the list of financial entities listed on the EU stock markets and accounting amounts required to perform our value relevance study.

Second, we download from the company web sites all the available documents useful to find information that the IASB (2010) requires to disclose. Analysing these documents, we find that there are entities that provide such information in a specific chapter of the annual report (n=163); other entities provide information in an annual report without distinguishing a separate part (n=284); finally, there are entities that do not provide such information in any document (n=49)3. This is a reason that justifies our interest for annual report because entities provide information within the document and no in a separate one.

Third, we complete our database with several dummies that control for the presence or the absence in annual reports of information that IASB (2010) requires to disclose for each macro-component. In detail, for the nature of the business – the first macro-component of IASB (2010) operationalized in our database with the acronym NBit – we look for information that concern: the industry (nbiit); the main markets (nbmit); the competitive position (nbcit); the environment (nbeit); the product, services, processes and distribution (nbpit); the structure (nbstit); the value creation (nbvit). For the objective and strategies (OSit) the information the IASB (2010) requires to disclose that we look for in annual reports regard the market trends (osmit) and the threats and opportunities (ostit). For resources, risks and relationships, the IASB (2010) requires to disclose detailed information concerning the first category (the resources) and in particular the financing (refit), the human (rfhit) and the intellectual (rfiit) resources. We collected also two dummies to control for the presence of information concerning the risks (riit) and the relationships (rlit) that are particularly significant elements that characterize a BM of financial entities. Similarly, for results and prospects, we simply look for explanations of the performance of the entity during the period and at the end of that period (for results) and targets for financial and non-financial measures (for prospects). For the critical performance measurements – the last macro-component – we look for the financial ones (pmfit) the non-financial ones (pmnfit) and the comparative analyses (pmcit).

The dummies whose names are in capital letters, that identify the five macro-components that the IASB (2010) requires to disclose, are equal to 1 if entities provide information in annual reports for the majority of the elements that the IASB practice statement requires to disclose for each macro-components, information that we identified with dummies whose names are in small letters. Therefore, dummies whose names are in capital letters not only control for the presence or the absence of information disclosed in annual reports, but are a proxy of the quantity of information. In fact, taking NBit as example, entities that have NBit equal to 1 disclose more information related to the industry, the main markets, the competitive position, the environment, the product, services, processes and distribution, the structure and the value creation compared with entities that have NBit equal to 0.

Once operationalized our variables, to verify our research hypothesis, at an aggregate level, we build a composite indicator (BMit) that measures the degree of compliance with IASB (2010) whose five macro-components, according to our theoretical framework, constitute the core elements of the BM of financial entities.

The possible values that this metric could assume range from 0 to 1, being the row mean of 5 dummies identified by capital letters. So, to cluster entities in two groups, according to the quantity of information that each entity provides in annual reports, we generate a dummy variable dBMit splitting at the median, within every country and for each year, the metric BMit. Entities that have dBMit equal to 0 are those that provide a limited disclosure of their BMit. Otherwise, entities that have dBMit equal to 1 are those that provide more information of their BM. Because disclosure practices can vary across years and countries, the median has been computed for every year and country.

Once assessed BMit and dBMit, we implement our model to assess the value relevance of accounting amounts. In detail, we use the following specification that includes between regressors interaction terms to control for the difference in value relevance of accounting amounts depending on the magnitude of the BM disclosure:

where, MVit, refers to the market value of equity of the firm i at the time t. NIit, are the reported earnings of the firm i at the time t. BVit, is the book value of the firm i at the time t. dBMit is the dummy variable generated splitting at the median the variable BMit. Tt-1 and Cc-1 are dummy variables that control for the time and the country fixed-effects4 and avoid that omitted variables could bias our research results.The specification includes variables deflated by the market capitalization at the reporting date following the Easton and Sommers (2003) procedure and winsorised to mitigate the possible biases due to the scale effect.

Assuming as measure of value relevance the magnitude of the statistically significant regression coefficients (e.g., Van Cauwenberge & De Beelde, 2010), those of Eq. (1) have a key role to test our hypothesis. In particular:

- •

α0 is the intercept of the regression line for entities that poorly comply with IASB (2010) and so provide a limited disclosure of the five macro-components.

- •

α1 is a measure of value relevance of earnings disclosed by entities that provide a limited disclosure of their BM;

- •

α2 is a measure of value relevance of book value disclosed by those entities that provide a limited disclosure of their BM;

- •

α3 measures the difference between the intercepts of the observations that provide a wide and a limited disclosure of their BM. Therefore, the sum of α0 and α3 is the intercept of entities that provide a wide disclosure of their BM;

- •

α4 measures the difference of the value relevance of earnings reported by entities that extensively and poorly disclose their BM. Consequently, α1+α4 is a measure of value relevance of earnings disclosed in annual reports of those entities that provide a wide disclosure of their BM.

- •

α5 measures the difference of the value relevance of book value of entities that extensively and poorly disclose their BM. Consequently, α2+α5 is a measure of value relevance of book value disclosed in annual reports of those entities that provide a wide disclosure of their BM.

Our research hypothesis is validated if α1+α4 is greater than α1. In this case, the reported earnings of entities that provide a wide disclosure of the core elements of the BM, required by the IASB (2010) practice statement, are more value relevant than those disclosed by entities that provide a limited disclosure. Correspondingly, if α2+α5 is greater than α2, the reported book value of entities that provide a wide disclosure of their BM is more value relevant than the one disclosed by entities that provide a limited voluntary disclosure of their BM. This is possible if the regression coefficients α4 and α5 are statistically significant and have a positive sign.

After the analysis at aggregate level, we verify whether, also at a disaggregate level, our research hypothesis continues to be validated. In detail, we test whether and how the disclosure of the single five macro-components of IASB (2010) positively affects the value relevance of accounting amounts. In fact, being quite different in nature, we expect to find a different capability of such macro-components to increase the value relevance of accounting amounts. This analysis, in the extent of which continues to validate the expected findings described above, provides a first clue of what elements of BM are more able to positively affect the VR of accounting amounts. To avoid problems of multicollinearity5, we will not use a single equation, but the following five specifications of the price model:

where NBit, is a dummy variable that controls for the disclosure of information regarding the nature of the business; OSit, is a dummy variable that controls for the disclosure of information regarding the organization and strategy; RRRit, is a dummy variable that controls for the disclosure of information regarding the resources, the risks and the relationships. RRR is the row mean of three dummies that regard the entities’ resources, risks and relationships6; ROit is a dummy variable that controls for the disclosure of information regarding results and prospects; PMit is a dummy variable that controls for the disclosure of information regarding the performance measures.All the specifications that we use to test our hypothesis, both at an aggregate and disaggregate level, have common characteristics regarding the operationalization of the variables and of the interpretation of the regression coefficients.

In the last part of our paper, we perform some sensitivity analyses to validate the robustness of findings. The first and the second one re-estimate Eqs. (1)–(6) with different metrics that control for information disclosed according to the requirement of IASB (2010) due to the importance of the design of indexes that measure disclosure of information (Bravo, Navarro, & Trombetta, 2009).

In our first test, we regress MV on NI, BV and their interactions with a coverage index, that we calculate at firm-level scaling the number of items disclosed by the company and the total number of possible items. At an aggregate level the items are 18 (nbiit; nbmit; nbcit; nbeit; nbpit; nbstit; nbvit; osmit; ostit; refit; rfhit; rfiit; riit; rlit; roit; pmfit; pmnfit; pmcit). At a disaggregate level their number changes according to the requirement of the Practice statement (7 items for the nature of the business; 2 for organization and strategy; 5 for resources, the risks and the relationships; 1 for results and prospects and 3 for the performance measures).

In the second test, accounting amounts of the price model interact with dBMit calculated after having ranked entities according to the quantity of information disclosed in annual report. For each macro-component that the IASB (2010) requires to disclose, we rank the entities analyzed depending on information disclosed in annual report complying with the practice statement requirements. In this test, we control for the quantity of information depending on the number of dummies (whose name is in small letters) that have values equal to 1. Entities that detail each macro-components with the information required by the IASB (2010) occupies the top of the rank. Otherwise, entities that provide less information are at the bottom of the rank. In this test, BMit is the row mean of the five ranks. For dBM, it is calculated splitting at the median, within every country and for each year, the metric BMit. Entities that have dBMit equal to zero are those that provide a limited disclosure of their BMit. Otherwise, entities that have dBMit equal to one are those that extensively disclose the information of their BM required by the non-mandatory IASB (2010) practice statement. We did this test to control not only for the quantity of information provided by the single entitites, but – thanks to the use of a rank – taking into account the information also provided by the other entities. In fact, while in the main analysis dBMit controls for the quantity of information provided in annual reports without considering the information provided by the other entities, in this sensitivity dBMit controls for quantity of information taking also into account the information that the other entities provide in annual report. The same exercise is repeated at disaggregate level when we have variables that allow us to build a rank for each macro-component.

In the third test, we verify whether the presence of financial entities listed in U.K., which are obliged to disclose their BM by national law, biases our conclusions.

In the final test, we look forward firm characteristics that could have been driven our research results, such as the size or the regulatory capital of the entity.

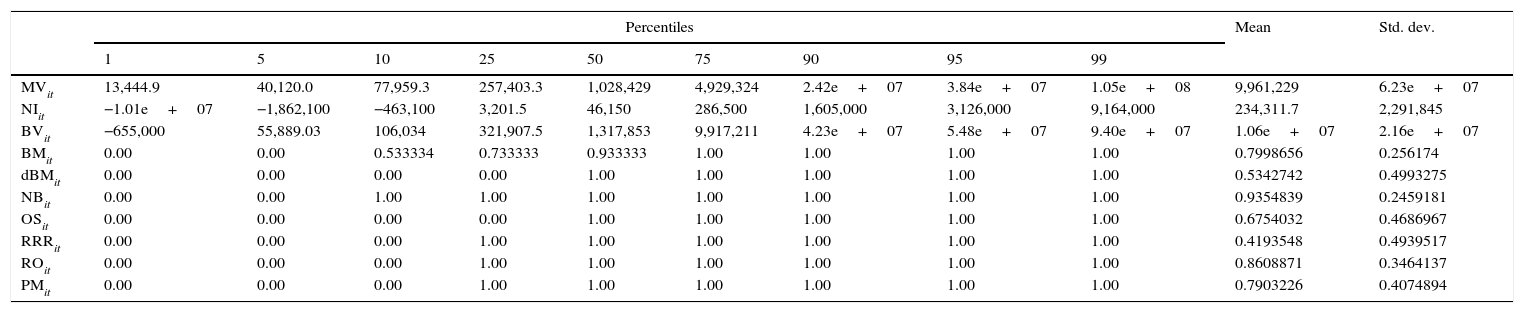

Empirical findingsDescriptive statisticsTables 2 and 3 summarize the main descriptive statistics (percentiles, means, standard deviations and correlation coefficients) of both the dependent and the independent variables used to estimate Eqs (1)–(6). At first glance, the values of the median and the mean of such variables – that seem quite different from each other probably due to the presence of outliers – justified the decision to deflate and winsorise variables to avoid biases to research results.

Descriptive statistics.

| Percentiles | Mean | Std. dev. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 10 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 90 | 95 | 99 | |||

| MVit | 13,444.9 | 40,120.0 | 77,959.3 | 257,403.3 | 1,028,429 | 4,929,324 | 2.42e+07 | 3.84e+07 | 1.05e+08 | 9,961,229 | 6.23e+07 |

| NIit | −1.01e+07 | −1,862,100 | −463,100 | 3,201.5 | 46,150 | 286,500 | 1,605,000 | 3,126,000 | 9,164,000 | 234,311.7 | 2,291,845 |

| BVit | −655,000 | 55,889.03 | 106,034 | 321,907.5 | 1,317,853 | 9,917,211 | 4.23e+07 | 5.48e+07 | 9.40e+07 | 1.06e+07 | 2.16e+07 |

| BMit | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.533334 | 0.733333 | 0.933333 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.7998656 | 0.256174 |

| dBMit | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.5342742 | 0.4993275 |

| NBit | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.9354839 | 0.2459181 |

| OSit | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.6754032 | 0.4686967 |

| RRRit | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.4193548 | 0.4939517 |

| ROit | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.8608871 | 0.3464137 |

| PMit | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.7903226 | 0.4074894 |

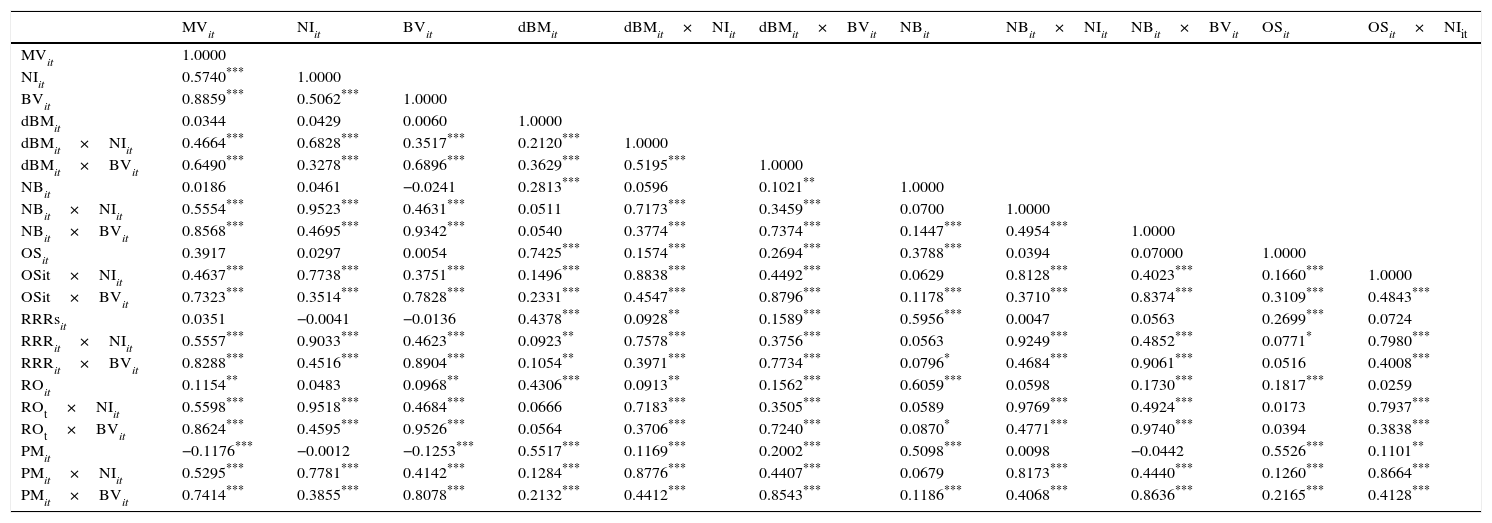

Correlation matrix.

| MVit | NIit | BVit | dBMit | dBMit×NIit | dBMit×BVit | NBit | NBit×NIit | NBit×BVit | OSit | OSit×NIit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVit | 1.0000 | ||||||||||

| NIit | 0.5740*** | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| BVit | 0.8859*** | 0.5062*** | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| dBMit | 0.0344 | 0.0429 | 0.0060 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| dBMit×NIit | 0.4664*** | 0.6828*** | 0.3517*** | 0.2120*** | 1.0000 | ||||||

| dBMit×BVit | 0.6490*** | 0.3278*** | 0.6896*** | 0.3629*** | 0.5195*** | 1.0000 | |||||

| NBit | 0.0186 | 0.0461 | −0.0241 | 0.2813*** | 0.0596 | 0.1021** | 1.0000 | ||||

| NBit×NIit | 0.5554*** | 0.9523*** | 0.4631*** | 0.0511 | 0.7173*** | 0.3459*** | 0.0700 | 1.0000 | |||

| NBit×BVit | 0.8568*** | 0.4695*** | 0.9342*** | 0.0540 | 0.3774*** | 0.7374*** | 0.1447*** | 0.4954*** | 1.0000 | ||

| OSit | 0.3917 | 0.0297 | 0.0054 | 0.7425*** | 0.1574*** | 0.2694*** | 0.3788*** | 0.0394 | 0.07000 | 1.0000 | |

| OSit×NIit | 0.4637*** | 0.7738*** | 0.3751*** | 0.1496*** | 0.8838*** | 0.4492*** | 0.0629 | 0.8128*** | 0.4023*** | 0.1660*** | 1.0000 |

| OSit×BVit | 0.7323*** | 0.3514*** | 0.7828*** | 0.2331*** | 0.4547*** | 0.8796*** | 0.1178*** | 0.3710*** | 0.8374*** | 0.3109*** | 0.4843*** |

| RRRsit | 0.0351 | −0.0041 | −0.0136 | 0.4378*** | 0.0928** | 0.1589*** | 0.5956*** | 0.0047 | 0.0563 | 0.2699*** | 0.0724 |

| RRRit×NIit | 0.5557*** | 0.9033*** | 0.4623*** | 0.0923** | 0.7578*** | 0.3756*** | 0.0563 | 0.9249*** | 0.4852*** | 0.0771* | 0.7980*** |

| RRRit×BVit | 0.8288*** | 0.4516*** | 0.8904*** | 0.1054** | 0.3971*** | 0.7734*** | 0.0796* | 0.4684*** | 0.9061*** | 0.0516 | 0.4008*** |

| ROit | 0.1154** | 0.0483 | 0.0968** | 0.4306*** | 0.0913** | 0.1562*** | 0.6059*** | 0.0598 | 0.1730*** | 0.1817*** | 0.0259 |

| ROt×NIit | 0.5598*** | 0.9518*** | 0.4684*** | 0.0666 | 0.7183*** | 0.3505*** | 0.0589 | 0.9769*** | 0.4924*** | 0.0173 | 0.7937*** |

| ROt×BVit | 0.8624*** | 0.4595*** | 0.9526*** | 0.0564 | 0.3706*** | 0.7240*** | 0.0870* | 0.4771*** | 0.9740*** | 0.0394 | 0.3838*** |

| PMit | −0.1176*** | −0.0012 | −0.1253*** | 0.5517*** | 0.1169*** | 0.2002*** | 0.5098*** | 0.0098 | −0.0442 | 0.5526*** | 0.1101** |

| PMit×NIit | 0.5295*** | 0.7781*** | 0.4142*** | 0.1284*** | 0.8776*** | 0.4407*** | 0.0679 | 0.8173*** | 0.4440*** | 0.1260*** | 0.8664*** |

| PMit×BVit | 0.7414*** | 0.3855*** | 0.8078*** | 0.2132*** | 0.4412*** | 0.8543*** | 0.1186*** | 0.4068*** | 0.8636*** | 0.2165*** | 0.4128*** |

| OSit×BVit | RRRit | RRRit×NIit | RRRit×BVit | ROit | ROit×NIit | ROit×BVit | PMit | PMit×NIit | PMit×BVit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSit×BVit | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| RRRsit | 0.0568 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| RRRit×NIit | 0.3830*** | 0.0990** | 1.0000 | |||||||

| RRRit×BVit | 0.7394*** | 0.2115*** | 0.5167*** | 1.0000 | ||||||

| ROit | 0.1286*** | 0.4845*** | 0.0408 | 0.1656*** | 1.0000 | |||||

| ROit×NIit | 0.3659*** | −0.0080 | 0.9320*** | 0.4731*** | 0.1010** | 1.0000 | ||||

| ROit×BVit | 0.8135*** | 0.0607 | 0.4750*** | 0.9279*** | 0.2158*** | 0.4911*** | 1.0000 | |||

| PMit | 0.1513*** | 0.4117*** | 0.0617 | −0.0556 | 0.2509*** | −0.0115 | −0.0765* | 1.0000 | ||

| PMit×NIit | 0.4161*** | 0.0800* | 0.8036*** | 0.4444*** | 0.0334 | 0.7985*** | 0.4247*** | 0.1332*** | 1.0000 | |

| PMit×BVit | 0.8965*** | 0.0605 | 0.4210*** | 0.7696*** | 0.1305*** | 0.4018*** | 0.8395*** | 0.2327*** | 0.5179*** | 1.0000 |

The analysis of the market value, the dependent variable of our models, highlights only positive observations being this variable positive skewed. For independent variables, net income and book value of equity, descriptive statistics highlights positive observation at least at 75% (for net income) and at 95% (for book value of equity) of cases. As regards the mean value and standard deviation of data collected, we find that the mean value of net income is between the 50th and 75th percentile. The one of book value of equity is between the 75th and 90th percentile.

As to BMit, we note that at least 5% of entities does not comply with IASB (2010) and gives no information about the BM; at least 25% of entities extensively comply with IASB (2010) and, according to our framework, gives an extensively disclosure of their BM; other entities partially comply with IASB (2010) that gives some information about their BM.

Moving to the five dummy variables that control for the presence of information required by IASB (2010) we find that, within the macro-components as defined above, at least 90% of entities of our sample give information about the nature of the business. For what concerns the information about Performance measures, Results and prospects and Resources, risks and relationships, at least 75% of entities are compliant with IASB (2010) requirement. Finally, the disclosure about objectives and strategies is given by at least 50% of entities included in our sample.

For the correlation coefficients, as reported in Table 3, we find many positive correlations, statistically significant at 1%. Statistics not tabulated in the table show that despite the high correlation between the independent variables, our results are not biased by multicollinearity being the mean value of variance inflation factor (VIF) of our specifications lower that the level of VIF that the econometric literature (Greene, 2003) considers acceptable to run regression without multicollinearity problems.

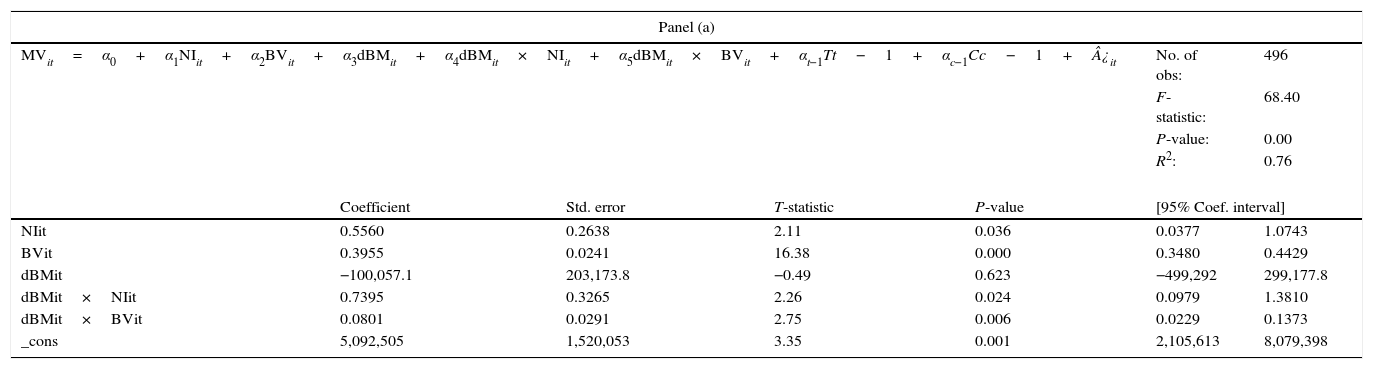

ResultsTable 4 discloses the output of the regression model with interaction terms that we used to test our research hypothesis.

Results (main analysis – Eq. (1)).

| Panel (a) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVit=α0+α1NIit+α2BVit+α3dBMit+α4dBMit×NIit+α5dBMit×BVit+αt−1Tt−1+αc−1Cc−1+¿it | No. of obs: | 496 | ||||

| F-statistic: | 68.40 | |||||

| P-value: | 0.00 | |||||

| R2: | 0.76 | |||||

| Coefficient | Std. error | T-statistic | P-value | [95% Coef. interval] | ||

| NIit | 0.5560 | 0.2638 | 2.11 | 0.036 | 0.0377 | 1.0743 |

| BVit | 0.3955 | 0.0241 | 16.38 | 0.000 | 0.3480 | 0.4429 |

| dBMit | −100,057.1 | 203,173.8 | −0.49 | 0.623 | −499,292 | 299,177.8 |

| dBMit×NIit | 0.7395 | 0.3265 | 2.26 | 0.024 | 0.0979 | 1.3810 |

| dBMit×BVit | 0.0801 | 0.0291 | 2.75 | 0.006 | 0.0229 | 0.1373 |

| _cons | 5,092,505 | 1,520,053 | 3.35 | 0.001 | 2,105,613 | 8,079,398 |

| Panel (b) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eq. (2) | Eq. (3) | Eq. (4) | Eq. (5) | Eq. (6) | ||||||

| No. of obs: | 496 | 496 | 496 | 496 | 496 | |||||

| F-statistic: | 129.95 | 69.10 | 70.86 | 68.23 | 68.11 | |||||

| P-value: | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||

| R2: | 0.8580 | 0.7627 | 0.7672 | 0.7604 | 0.7601 | |||||

| Coeff. | P | Coeff. | P | Coeff. | P | Coeff. | P | Coeff. | P | |

| NIit | 0.5807 | 0.38 | 0.4934 | 0.04 | 0.2716 | 0.83 | 0.4564 | 0.08 | 0.2938 | 0.69 |

| BVit | 0.4202 | 0.00 | 0.4008 | 0.00 | 0.3466 | 0.00 | 0.4054 | 0.00 | 0.4280 | 0.00 |

| NBit | −872,143 | 0.22 | ||||||||

| NBit×NIit | 1.2852 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| NBit×BVit | 0.0845 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| OSit | −226,532 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| OSit×NIit | 1.0200 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| OSit×BVit | 0.0712 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| RRRit | −309,908 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| RRRit×NIit | 1.0433 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| RRRit×BVit | 0.1245 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| ROit | −371,253 | 0.22 | ||||||||

| ROit×NIit | 1.0221 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| ROit×BVit | 0.0592 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| PMit | −905,241 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| PMit×NIit | 1.6130 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| PMit×BVit | 0.0744 | 0.17 | ||||||||

| _cons | 4.92e+06 | 0.00 | −9.87e+08 | 0.00 | 2.74e+06 | 0.00 | 2.41e+06 | 0.00 | 1.92e+06 | 0.00 |

Table 4 (Panel a) shows that the coefficient of earnings (NIit) disclosed by entities that provided a limited disclosure of their BM is 0.5560. The interaction term (dBM×NI) is positive (0.7395) and statistically significant at 5%. This suggests that the regression coefficient (and so the value relevance) of earnings, disclosed by entities that provided a wide disclosure of their BM, is higher (1.2955, equal to the sum of the coefficient of NI and dBM×NI) and statistically different from the one of earnings disclosed by entities that provided a limited disclosure of their BM. Results not tabulated in the table show also that running regression above the cluster of entities that provided a wide disclosure of their BM, we found that such coefficient is statistically significant at 1%.

Similarly, the coefficient of book value (BVit) disclosed by entities that provided a limited disclosure of their BM is 0.3955. Similarly to the interaction term of net income, also the interaction term of book value (dBM×BV) is positive (0.0801) and statistically significant at 1%. This suggests that also the coefficient of book value disclosed by entities that provided a wide disclosure of their BM is higher (0.4756, equal to the sum of the coefficient of BV and dBM×BV) and statistically different from the value relevance of book value disclosed by the other group of entities. Also in this case, results not tabulated in the table show also that running regression above the cluster of entities that provided a wide disclosure of their BM, we found that such coefficient is statistically significant at 1%.

Table 4 (Panel b) shows findings of disaggregate level analysis where we investigate whether and in what extent the disclosure of the single macro-components of the IASB (2010) has the same capability to positively affect the value relevance of accounting amounts. Results confirm our research hypothesis and lead us to highlight some interesting implications.

For what concern NBit, the voluntary disclosure of the nature of the business has positive effects on value relevance of accounting amounts and enhances the value relevance of earnings and book value; in fact, the regression coefficients of the interaction terms are positive and statistically significant at 10% and 5%, respectively.

The disclosure of information related to OSit, RRRit and ROit produces common effects on the value relevance of earnings being the coefficients of interaction terms statistically significant at 1%. Instead, the effect on book value of equity is different being the coefficient of the interaction term significant at 5% for OSit, at 1% for RRRit and at 10% for ROit.

Finally, for PMit, we found that while the value relevance of earnings increases when entities provide the voluntary disclosure of results and prospects (dBM×NIit is positive and statistically significant), our results show that the voluntary disclosure of such information does not change the value relevance of book value of equity, being the interaction term PMit×BVit not statistically significant (p-value=17%).

Findings achieved in our sensitivity analyses continue to validate our hypothesis.

In the first and in the second test, we verify whether methodological choices behind the construction of the disclosure index used in the main analysis affect our research results.

In the first sensitivity, a coverage index and its interactions with accounting amounts (NI and BV) is used to test the robustness of our findings. At an aggregate level, such interactions are positive (+2.85 for NI and +0.14 for BV) and statistically significant at 1% validating our conclusion that there is a statistically significant difference between entities that disclose and that do not disclose information regarding their BM and that the more entities disclose such information the higher accounting amounts are value relevant. At a disaggregate level, results lead to the same conclusions except for the interactions between the coverage index calculated for the second macro-component (organization and strategy) that is not statically significant.

In the second sensitivity, we calculate BM as a row mean of a rank. Using a specification with interaction terms similar to the one of equation (1), findings validate our research hypothesis. The coefficients of earnings and book value of entities that provide a wide disclosure of their BM are positive, statistically significant and higher than the coefficients of entities that provide a limited disclosure of their BM. For earnings, while entities that extensively comply with IASB (2010) have a regression coefficients of 1.45, for book value, the coefficient is equal to 0.47. In entities that poorly comply with IASB (2010), the regression coefficient of earnings is 0.71 and the one of book value is 0.42. The same exercise did at disaggregate level validate findings achieved in the main analysis.

In the third test, we verify whether the presence of financial entities listed in U.K., which are obliged to disclose their BM by national law, biases our conclusions. Running regressions on a sample of 424 firm-year observations, our hypothesis is validated. Both earnings and book value increase their value relevance both at an aggregate and at a disaggregate level in entities that disclose the macro-components of IASB (2010).

In the final test, we look forward firm characteristics that could have been driven our research results, such as the size or the regulatory capital of the entity. Using total assets and the total regulatory capital as proxies of such characteristics, a hierarchical cluster analysis suggested us that the 124 entities analyzed cannot be clustered in different groups, because they are not statistically different from each other in terms of total asset and regulatory capital. Actually, the entities analyzed are listed in European countries, belong to the same sector and are characterized by a high level of transparency; such transparency allowed us to collect data from the documents published on the companies web site of the entities analyzed. The cluster analysis splits them in different groups, but over 90% of the entities belongs to the same group. This does not allow us to re-run our regressions above different clusters and provides evidence that being the entities analyzed very similar from each other, we could be quite confident that is the BM disclosure (and not other characteristics) to positively affect the value relevance of accounting amounts.

DiscussionThe magnitude of the regression coefficients disclosed in Table 4 validates, at an aggregate and disaggregate level, our hypothesis that accounting amounts are more value relevant in entities that extensively comply with IASB (2010) and so provide a wide disclosure of their BMs, compared with entities that provide a limited disclosure of their BM. The increase of the value relevance made accounting amounts more useful and reliable (Barth et al., 2001). This is probably due to the desirable effects of the voluntary disclosure of the elements that IASB (2010) requires to disclose, that is, the reduction of agency costs (Johansson & Malmstrom, 2013), the signal as a powerful tool for convincing external providers of funds to finance the business (Johansson & Malmstrom, 2013; Mishra & Zachary, 2015) and, last but not least, the selectively increase of legitimacy with customers (Snihur & Zott, 2013).

Interesting insight comes from the analysis at disaggregate level from which we learn that the voluntary disclosure of the single IASB (2010) macro-components positively affects the value relevance of accounting amounts. Respect to the aggregate level, the disaggregate analysis shows that the disclosure of information related to each macro-component affects in different manner the value relevance of accounting amounts. In fact, the value relevance of earnings seems to benefit more than book value of equity of the voluntary disclosure of the IASB (2010) macro-components that, according to our theoretical framework identify the key elements of the financial entities’ BM. It is very interesting the findings that the single macro-components are more able to positively affect the value relevance of earnings and that the third macro-component resources, risk and relationships is the one where both the interaction terms (RRR×NI and RRR×BV) are statistically significant at 1% level. The major ability to positively affect the earnings coefficient is probably due to the fact that the voluntary disclosure of the BM facilitates investors to interpret all the information useful to assess the firm value. Because the earnings variables have a key role in determining such value, their value relevance improves when entity discloses information that regard its BM. The significance of the interaction terms suggests a strong difference between the value relevance of accounting amounts disclosed in annual reports of entity that disclose information regarding the resources, the risks and the relationships.

From the first two sensitivity analyses, we learn that also using different design for our disclosure indexes, the research hypothesis continues to be validated. In the first test using a coverage index and in the second one also controlling for information provided by other entities (e.g., with the use of a rank). As far we are concerned, both the coverage index and the choice to rank entities according to the information regarding the elements that the Practice statement requires to disclose for each macro-component are two possible manners to control for quantity of information disclosed in annual report.

From the other tests we learn that the presence in the sample of entities listed in UK does not bias research results and that is the BM and no other firms’ characteristics to drive research results.

Conclusion remarksOver time, the BM concept, initially related only with internet companies, has drawn a growing attention of academics – involved in different fields of research – regulators and practitioners. Despite the importance of BM topics in the literature, a generally accepted definition of what is BM still lacks. Moving from the interest around this topic, in this paper, we investigated the usefulness of its disclosure in increasing the value relevance of accounting amounts. To do so, in the second section of this work, we quoted several research that strengthen our argument that the disclosure required by the non-mandatory “Management Commentary Practice Statement” (IASB, 2010) sheds lights on the entities’ BM. Actually, the elements that the standard setter asks to disclose, in the annual report or in a separate management commentary, not only facilitate investors in using accounting amounts to assess the firm value, but could be also considered an archetypal of the BM of firms, in particular, those belonging to the financial sector, being aware that also other elements, not covered by IASB (2010), could be useful to describe a BM.

Entities that comply with IASB (2010) and provide a wide disclosure of their BM disclose more value relevant accounting amounts compared with entities that do not comply with IASB (2010) and so that provide a limited disclosure of their BM.

Taking into account the strict relation of some macro-elements of IASB (2010) with certain financial institution peculiarities, we test such hypothesis by having as a reference a sample of 124 financial intermediaries listed in the EU over the period 2010–2013. Using a price model, we assess and compare the value relevance of accounting amounts and we found that those disclosed by entities that extensively comply with IASB (2010) are more value relevant than the ones that poorly comply with the same document. Our findings, included those of several sensitivity analyses, validate our research hypothesis and confirm the opportunity for investors to find in annual report or in a separate management commentary information that regards the BM of the company.

Such results have implications for European regulators interested for different motivations in financial entities. In particular, they could be useful for the EBA (the authority that maintains financial stability in the EU and safeguards the integrity, efficiency and orderly functioning of the banking sector) and the IASB (a standard setter that issues accounting standards that bring transparency, accountability and efficiency to financial markets around the world). These institutions have different aims but they have in common the interest toward the BM concept. On the one side, EBA during its monitoring activity has to verify if the risk-taking process, the governance arrangements, the prices of assets and liabilities offered to clients, the firm performance and the adequacy of the leverage ratio are coherent with the BM of the entity. On the other side, the IASB is aware that the accounting policies for financial instruments will be influenced by the BM as of 1st January 2018 with the IFRS 9 first-time adoption. From this paper, they can learn which are the macro-components useful to identify a BM in financial entities. In our opinion, the knowledge of such macro-components will help them in their different activities that justify their common interest toward the BM concept. In addition, from this paper, they can learn that the disclosure of such elements enhances the value relevance of accounting amounts. This is important not only for IASB but also for the EBA that has a strong interest in promoting sound and high quality accounting and disclosure standards for the banking and financial industry, as well as transparent and comparable financial statements that strengthen market discipline.

Despite the theoretical contribution of the paper and its implications for standard setters discussed in the introduction of this work, a possible limitation of this study is that the research controls for quantity and not for the quality of the BM disclosure. In previous disclosure studies there is consensus that the quantity and the quality of accounting information are very different concepts and that the informativenes of disclosure is not necessarily related to the amount of information but to its quality (Beattie et al., 2004; Beretta & Bozzolan, 2004). Nevertheless, we can read in Beretta and Bozzolan (2004) that it is generally assumed that the quantity of information has an implication in determining its quality and so that quantity measures are often used as proxy for disclosure quality. Our study try to control for the quantity of information disclosed about the BM observing if entities disclose the majority of the elements that characterize each of the single macro-components (in the main analysis) and through a coverage index and a rank (in sensitivity analyses). Future research could control in different manner the quantity of information disclosed in annual reports, for instance using textual analysis based on the number of sentences within an individual annual report, which contain this information (Bravo, 2016).

Another possible limitation of the paper is the number of observations available for each country. The absence of any database that could provide all the data required to test the research hypotheses led to hand-collect data from the documents available on the company web sites of the entities analyzed. This manner of collecting data could produce a potential bias to the inference due to significant differences as to the number of entities analyzed for each country. However, the methodological choice to consider entities that belong to the same industry, i.e., the financial sector, listed in the European countries and that are subject not only to a common set of accounting standards, but also to the same regulatory framework should alleviate potential biases.

For the future development of this research, scholars could investigate if also other macro- components of the BM have the same capability with respect to the ones required by IASB (2010). As further future development, once the modern database will allow doing this research with more facility, scholars could test our research hypothesis analyzing entities that also belong to other industries. This will reinforce our arguments in favor of the BM disclosure and could lead standard setters to issue a new accounting standard that will require such disclosure.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The value creation is very significant for “The UK Corporate Governance Code” issued by the UK Financial Reporting Council. In fact, the document defined the BM as the basis on which the company generates or preserves value over the long term.

According to these scholars, the information environment concept is very broad and includes government reports on macroeconomic conditions, industry reports and trade association publications, firm-specific news in the financial press and reports issued by analysts and brokerage houses in addition to accounting reports, and vertical and intra-industry information transfers via sales industry reports.

The number of firm-year observations in brackets shows that companies were not necessarily consistent in their disclosure practices over time (Camfferman, 1997; Jones et al., 1998) validating findings achieved by academics that deal with voluntary disclosure practices. In detail, entities that one year disclose the IASB (2010) requirements in the annual report, the subsequent year report them in a separate documents.

The decision to include fixed effects is the result of test statistics that show how they are better than random effects.

A single equation with dummies and interaction terms between all the macro-components of the IASB (2010) and accounting variables (earnings and book value) has a mean VIF over 20, which the econometric literature (Greene, 2003, p. 58) considers the maximum acceptable to run regression without multicollinearity problems.

For the third macro-component of IASB (2010), we collected three different dummies to distinguish the three elements that, together with the nature of the business, in our opinion identify more than the other ones the business model of financial intermediaries.