In 2015, Spanish local governments began to apply a new accounting standard. The success achieved in its implementation is related with stimuli from outside the organization and with the institutional capacity – administrative and political – developed by it. Through an electronic questionnaire and several interviews carried out with municipal chief financial officers it has been shown that few actions to build the necessary institutional capacity were undertaken in the period prior to its implementation. The results show that the LGs did not attain the necessary institutional capacity and will have to continue allocating resources and time to improve it.

En 2015, los ayuntamientos españoles comenzaron a aplicar la nueva Instrucción de Contabilidad Pública Local. El éxito de su aplicación está relacionado tanto con los estímulos externos a la entidad como con la capacidad institucional (administrativa y política) desarrollada. Mediante un cuestionario electrónico y varias entrevistas a los interventores, se han identificado las acciones emprendidas en la etapa previa a la entrada en vigor de la norma, para lograr el desarrollo de la capacidad institucional necesaria. Los resultados muestran que el nivel alcanzado es mínimo y que los ayuntamientos deberán continuar destinando recursos y tiempo para mejorar el desarrollo de la capacidad institucional.

The adopting in 2010 of a new public accounting standard (hereafter, PAS), applicable to Spanish state public sector bodies, gave rise to a substantial modifying of the accounting model which reflected the legislative change that had already taken place in the Spanish private sector in 2007. An example of this is the supplying of management and financial information which enables administrators to make appropriate decisions and informs citizens of the result of the government teams’ management. This grants citizens the role of being one stakeholder more (Christianses & Van Peteghem, 2007). This reform means a step forward in the modernization process of the Spanish public administration which began in 1981.

A successful PAS implementation is crucial to attain other aims linked to new public management. This implementation is directly related to both the external stimuli which are brought to bear on the organization and the institutional capacity developed by it. This, in turn, is determined by the organization's capacity to interpret, understand and apply the principles and requirements included in the reform, the staff training and the availability of technical means (Covaleski & Dirsmith, 1988; Harun & Kamase, 2012; Powell & DiMaggio, 1991; Pozzoli & Ranucci, 2013). Anessi-Pessina, Nasi, and Steccolini (2008) show that in the case of Italian local governments, rational factors such as the size of the Local Government (hereafter, LG), dependence on the money market and the degree of complexity of the measures undertaken do not determine the applying of a new accruals-based accounting standard. However, they confirm that institutional factors, such as the CFOs’ perceptions and the geographical location, do condition this application. This is, moreover, consistent with the importance that those in charge give to enforcing the law. Likewise, they point out that it would be interesting to analyze the impact of other variables, such as competencies, skills, perceptions and managers’ and politicians’ resistance to change.

In this context, this study has as aim to determine if the obligatory application data of the new accounting instruction (hereafter, AI) the LGs have managed to develop the institutional capacity required to implement it successfully.

Empirical evidence has been obtained through electronic questionnaires and several interviews carried out with municipal CFO. The results obtained bring to light that at the date of the obligatory application of the AI the LGs did not attain the necessary institutional capacity and will have to continue allocating resources and time to improve it.

This work is pioneering because it identifies the main factors that influence the institutional capacity in Spanish LGs (the fifth largest country in European Union). So, the findings may provide a basis for other countries in the process of public sector accounting reform, to attempt to override the negative effects and enhance the positive factors identified in the study. It can specifically serve community countries as they currently are immersed in accounting reform processes of their respective public sectors in order to achieve a harmonization of information. The European Commission has proposed elaborating the European Public Sector Accounting Standards (hereafter, EPSAS) which take as an indisputable reference the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (hereafter, IPSAS) (Bergmann & Labaronne, 2013; Brusca & Gómez, 2013; Brusca & Martinez, 2016; Brusca, Montesinos, & Chow, 2013; European Commission, 2013).

This work has six sections. Following this introduction, there is a literature review of the supporting theoretical framework. After, the accounting reform process in Spanish LGs is described. Then, the aim and the methodology used are specified. The fifth section shows and analyzes the results obtained and the final section includes the conclusions.

Defining institutional capacityFrom the literature review it is noted that there is not a unique concept of institutional capacity. All the definitions or concepts can be grouped into four categories (Rosas, 2008; Rosas & Gil, 2013):

- (a)

Reported capacity, focused on means and administrative processes, adapted to the institution's potential to perform the tasks that they have been entrusted with (Nelissen, 2002). Oslak (2004), meanwhile, sees it as the availability and effective application of the material, technological and human resources which the State's administrative and productive apparatus has to manage the production of public value, overcoming its context's restrictions, conditions and threats. As a consequence, according to this author, the main factors which can influence institutional capacity are, among others, the quantity and quality of the human and material resources, the appropriateness of the participants’ individual capacities for the posts’ profiles and the assigning of tasks in the different management processes, and the stakeholders’ acceptance of the rules, subcultures and sanctions.

- (b)

Effective capacity, adapted to the action of a government. Repetto (2007) considers this to be the capacity of public management, alluding to those who are responsible for making policies, the means that they have to do so and which institutional rules they operate under.

- (c)

Capacity as a product, as the skills produced. Seen as the organization's skill to absorb responsibilities, carry out appropriate tasks effectively, efficiently and sustainably and strengthen its accountability (Burns, 2005; Grindle & Hilderbrand, 1995; Savitch, 1998).

- (d)

Capacity as process. Willems and Baumer (2003) define this as, on the one hand, the skill of governmental authorities to improve functions, solve problems and specify and achieve aims and, on the other hand, the ability to mobilize or adapt institutions to respond to a public problem. On the other hand, Chávez and Rayas (2006) associate this with the development of any institution's structure which enables it to take on its responsibilities in an orderly and coordinated way in the short, medium and long term.

As for its components, different authors (Alonso, 2007; Duque, 2012; Evans, 1996; Oslak & Orellana, 2001; Repetto, 2007; Tobelem, 1992) highlight:

- (a)

The administrative capacity, seen as the set of techno-bureaucratic skills required to achieve the official objectives. This is comprised of both the human resources and the organization itself.

Regarding the human factor, among other aspects they mention the number, variety and posts of civil servants; organizational and procedural factors which regulate aspects such as recruitment, promotion, salaries and ranking; human resources training; systems of awards and punishments; the individual capacity of the actors responsible for tasks in terms of information, motivation, knowledge/understanding and the skills required.

Concerning the organization, attention is paid to the availability of the financial resources necessary to carry out the tasks scheduled, to the organization's responsibilities, purposes and functions, to the structure and distribution of functions and responsibilities. Among other elements, the manner of organization, the legal authority to make other institutions comply with its programs, the management systems to improve the carrying out of tasks and specific functions, the intergovernmental relation, coordination and collaboration, the type and characteristics of the policies and programs which it designs and applies, as well the laws are also considered. This is directly related with the quantity and quality of the human and technical resources available (Duque, 2012).

- (b)

Political capacity. The political interaction which – structured in certain rules, standards and habits – the State's actors and the political system establish with the socio-economic sectors and those which operate in the international context. In this component stand out: (a) political participation, that is to say, who participate and how they do so; (b) negotiation, that is, the political will between the actors and their manner of negotiating; and (c) the power struggle, or to what extent the actors accept the existing distribution of power.

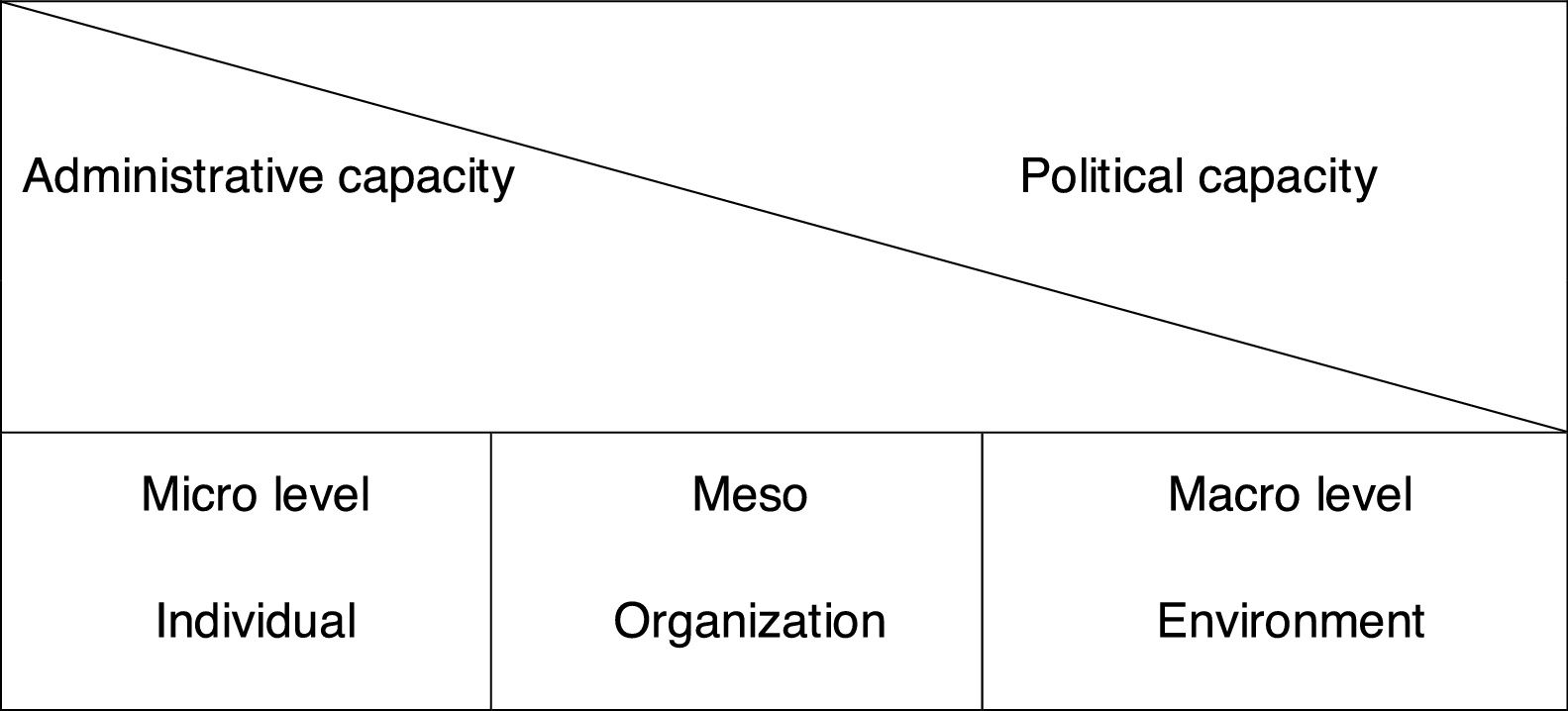

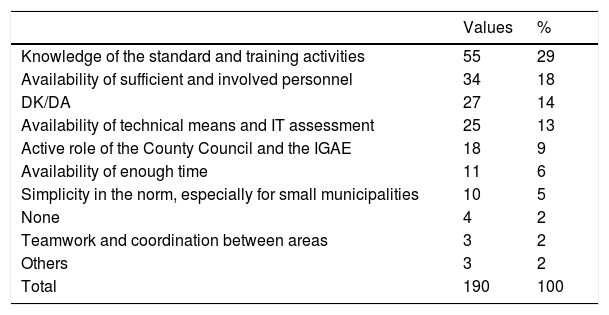

Both dimensions of institutional capacity are present, though with a different degree of intensity, at distinct infra- and extra-organizational levels (Forss & Venson, 2002; Willems & Baumer, 2003; Rosas, 2008).

As can be seen in Fig. 1, the micro level considers all those quantitative and qualitative variables which determine the performance of the staff within the organization (skills and aptitudes, degree of motivation, training levels, the existence of incentives, the staffing level necessary, etc.). At this level it is the administrative capacity which is mainly more present.

Nevertheless, no matter how decisive the human factor is to the success of any action or policy, its performances are not enough to achieve a relevant degree of institutional capacity. This level is therefore broadly related to the other levels.

The meso level is centered on the organization and, therefore, its management capacity. It will be directly related with the existence of clear and compatible missions, the provision of the necessary material resources, the development of management techniques appropriate to achieve the aims, leadership, organizational culture, communication and coordination systems, the managerial structures, etc. At this level the two dimensions are present, but the administrative capacity is more relevant.

Notwithstanding, the organization's performance depends not only on the individual but also on the country's institutional context. This is why this level is directly related with the macro level. The latter refers to the institutions and the economic, political and social environment within which the public sector is framed. The activities associated with this level are linked with the rules of the game of the economic and political system which governs the sector, legal and political changes, constitutional reform, and so forth.

At the macro level the political capacity is primarily present, but there also exists, though less relevant, the administrative capacity, given that the human resources and organizations are embedded in a broader institutional context (Rosas, 2008).

The analysis of the public sector's institutional capacity begins at the level of the individual. However, what happens there is clearly influenced by the other levels, in the same way as the administrative capacity is plainly influenced by politics and vice versa (Rosas & Gil, 2013).

It is therefore concluded that institutional capacity depends not only on there being coherent administrative organizations and experts who are prepared and motivated (administrative capacity), but also on the performance and engagement of the socio-political actors involved (political capacity). In this regard, this study agrees with Rosas (2008) that administrative capacity and political capacity are the cornerstones upon which institutional capacity is structured. This is why any evaluation of it must take into account these two components.

For the goal of this study, Oslak's (2004) definition of institutional capacity has been accepted, seeing it as the availability and effective application of the human, material and technological resources that the LG has to apply the new AI in both its administrative and political aspects, and the focus is mainly on the level of the individual and the organization.

Spanish public accounting process reformA new accounting reform process of the Spanish public sector was begun in 2010. Spain has adopted the international standards within its government accounting by means of approving a new PAS. This reform has been mainly aimed at achieving three objectives (Bergmann & Labaronne, 2013; Brusca & Gómez, 2013; Brusca & Martinez, 2016; Brusca & Montesinos, 2012; Brusca et al., 2013; Pérez, 2007, 2011):

- •

To attain accounting harmonization at different levels: (i) fostering a bridging of the gap with the private sector accounting standard, (ii) trying to achieve a homogenization of all the Spanish public administration's accounting systems both among each other and (iii) with international accounting standards. In this way, a harmonization of both IFRS elaborated by International Accounting Standard Board and the IPSAS elaborated by the International Public Sector Accounting Standard Board. IPSAS are currently the most important reference framework when different countries undertake accounting reforms. Harmonization is an essential requirement for achieving the necessary transparency and thus the market confidence, strengthening in this way citizens’ confidence in public administration and enhancing the comparability.

- •

To modernize governmental accounting and to improve the usefulness of the accounting information for management decision making, to ensure that the accounting reports obtained really serve to satisfy the users’ needs.

- •

To generalize the use of computerized and telematic means in accounting procedures.

- •

Several innovations have been introduced by the new PAS:

- -

The incorporation of a conceptual framework.

- -

New valuation criteria are introduced (market value, replacement cost, use value, amortized cost, among others).

- -

The statement of cash flows and the statement of changes in equity are included.

- -

The content of the Notes is expanded (financial ratios, budget ratios and public services cost information).

- -

These new procedures, criteria and accounting statements required a significant increase in the degree of technical complexity necessary to elaborate accounting information. The adoption of new accounting standard requires resources – investments in information technology systems and training- and political support (PwC, 2014).

All this reform process of the public accounting system can be equated with a process of geological sedimentation, in that the new laws modify and improve the existing ones but do not replace them completely (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011).

The legislator has opted to harmonize over time the accounting standard of all the bodies which make up the Spanish public sector in order to favor the comparability of the financial states in their different geographical areas.1 A gradual system was chosen to implement this reform. Thus, in 2010 the public accounting standard applicable to the General Administration of the State were adopted and, later, standards of development and application adapted to the different institutions – the AI – were drawn up. The AI is a detailed development of the content of the PAS. There are not significant changes between one text and the other.

Moreover, in Spain, unlike other countries (Pozzoli & Ranucci, 2013), the implementation has generally been carried out without performing prior pilot experiences. These could have detected the defects and benefits of the new regulation, reduced the resistance to change, and so forth.

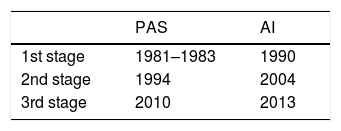

Centering on local governments, three AI have been adopted over time (in 1990, 2004 and the last in 2013 which came into force January 1st, 2015).

Comparing the years of adopting the PAS and the corresponding local AI, it is noted that there was a minimum of 5 years between the two dates (Table 1).

Taking into account the time gap that there had been in previous reforms between the publication of the PAS and that of the AI, the local authorities should have known that in the short to medium term their specific accounting standards were going to be modified and, as a consequence, in this period they ought to have undertaken the necessary actions to build the institutional capacity needed to successfully implement them.

Research questions and methodologyThe research analyzes the case of AI reform implementation in the Spanish LGs and tries to determine if the LGs have attained the institutional capacity required to successfully implement the new AI before January 1st, 2015.

The research questions have been determined on the basis of the elements identified by Oslak (2004) to define the institutional capacity at micro and meso levels and especially focusing them on their administrative aspect:

- •

Do the LGs have the necessary personnel resources to successfully tackle the implementation of the new AI?

- •

Has the staff been acquiring enough training to get to know the new AI prior to its application?

- •

Do the LGs have sufficient technical resources (software) to start implementing AI?

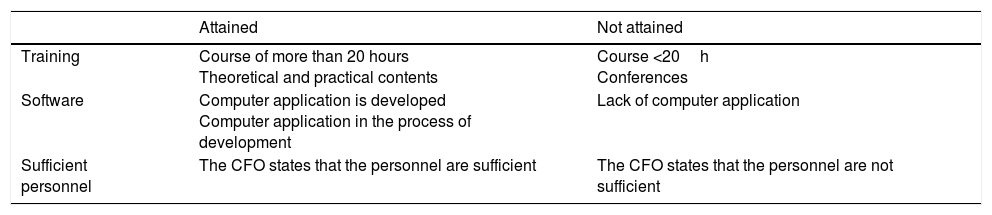

The necessary institutional capacity is reached when the answer to the three issues is affirmative. Table 2 shows the conditions established to consider the meaning of the answers to the previous questions.

Requirements to attain institutional capacity.

| Attained | Not attained | |

|---|---|---|

| Training | Course of more than 20 hours Theoretical and practical contents | Course <20h Conferences |

| Software | Computer application is developed Computer application in the process of development | Lack of computer application |

| Sufficient personnel | The CFO states that the personnel are sufficient | The CFO states that the personnel are not sufficient |

To answer these questions, it was decided to conduct descriptive and exploratory field research.

The information necessary to answer the research questions was obtained by combining two data collection methods – personal interviews and a questionnaire:

- (a)

Questionnaire. Between October 2014 and January 2015 the questionnaire was electronically disseminated among the CFOs of approximately 3000 municipalities, (we have not excluded any municipality by inhabitant criteria). 24 closed-open questions were structured in five blocks: (i) demographic profile; (ii) training received concerning accounting reform; (iii) opinions on main problems and benefits of the accounting standard; (iv) human and technical resources level available for implementing, and (v) involvement and support of politicians. The questionnaire was sent twice with the purpose of increasing the response level. The level of valid responses was 5.5%.

- (b)

Interviews. To capture the views of the people who have implemented the AI in the LGs, semi-structured interviews were undertaken between December 2014 and January 2015.2 These interviews were held with 20 CFOs in ten municipalities. As for the size of the LGs – a variable which conditions the complexity and the AI to apply – two local authorities with a population over 600,000 inhabitants were selected, another two with a population of about 100,000 inhabitants and six whose population was between 20,000 and 50,000 inhabitants. The interviews were not recorded and took place in the different LGs. Two members of the research team and the CFOs were always present. They lasted two hours on average. The authors used open-ended questions as guidance for discussion with the participants, but the interviewers were allowed to speak freely. The aim of the interviews was to go more deeply into the previous phases’ findings: (i) the main advantages and inconveniences that the CFOs have remarked in the new AI; (ii) the level of involvement and institutional and political support for the provision of the technical, human and training techniques necessary to guarantee the success of the implementation of the AI; and (iii) the actions carried out to train the staff in charge of its application.

About a week after each interview, the different members of the work team attending wrote up their conclusions and these were pooled. The document which gathers all the impressions and conclusions of the different interviewers was emailed to the respondents for them to nuance their statements and complete the information.

Techniques of statistical data analysis have been applied:

- •

Frequency tables have been used to study the answers to the questionnaires.

- •

Contingency tables have been developed to evaluate the relationship between the variables analyzed.

- •

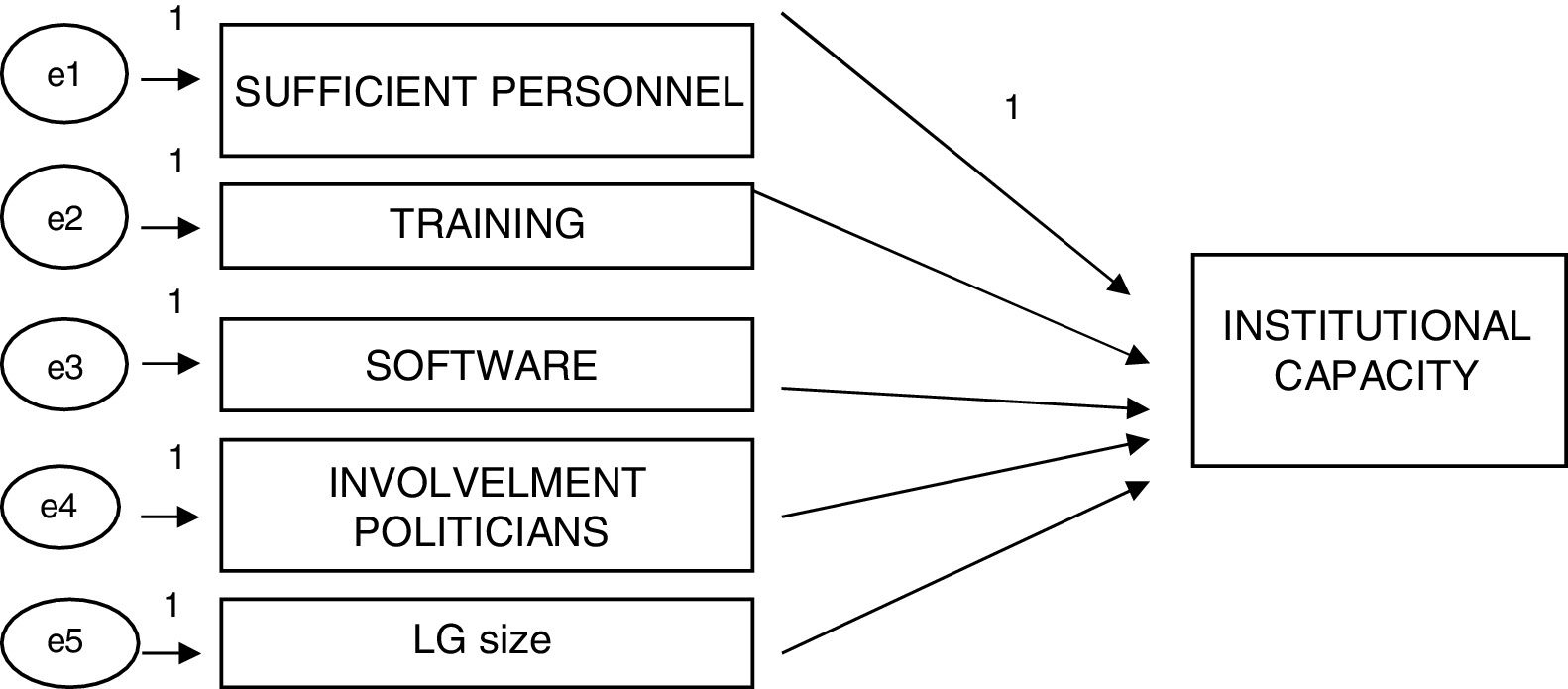

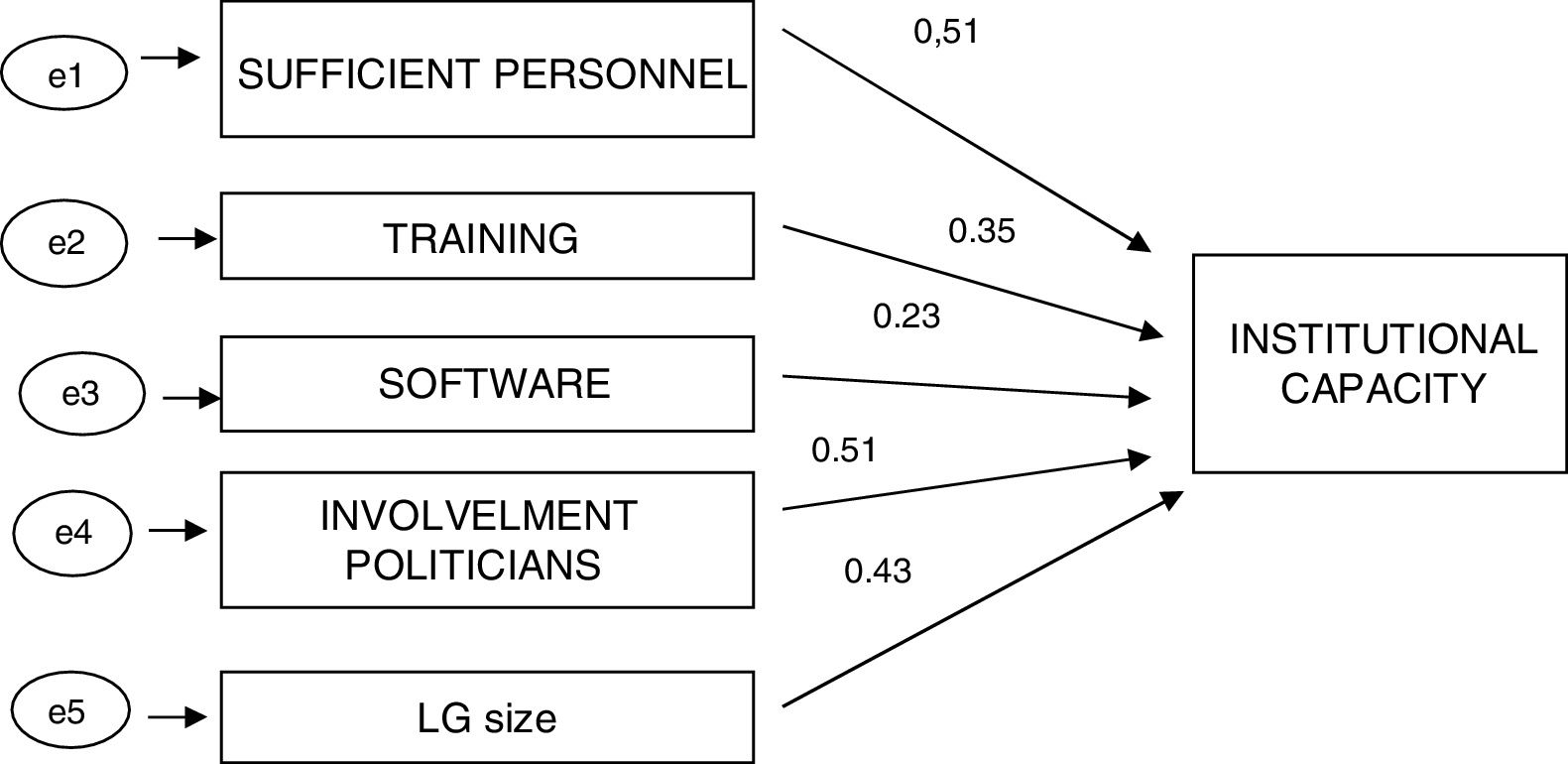

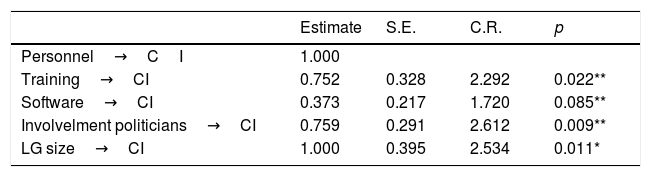

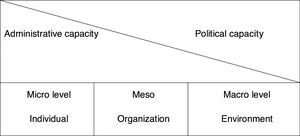

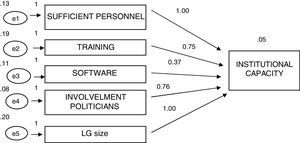

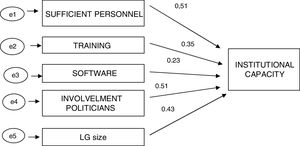

On the one hand, to test the model and determine the degree of influence of each independent variable in achieving institutional capacity a confirmatory factor analysis has been applied using covariance based structural equations modeling (Brown, 2015). As a result of the descriptive analysis carried out, in this model two additional variables have been incorporated to those considered by Oslak (2004) as determinants of the institutional capacity: the involvement of the politicians and the size of the local government (see Fig. 2).

The software used was AMOS.

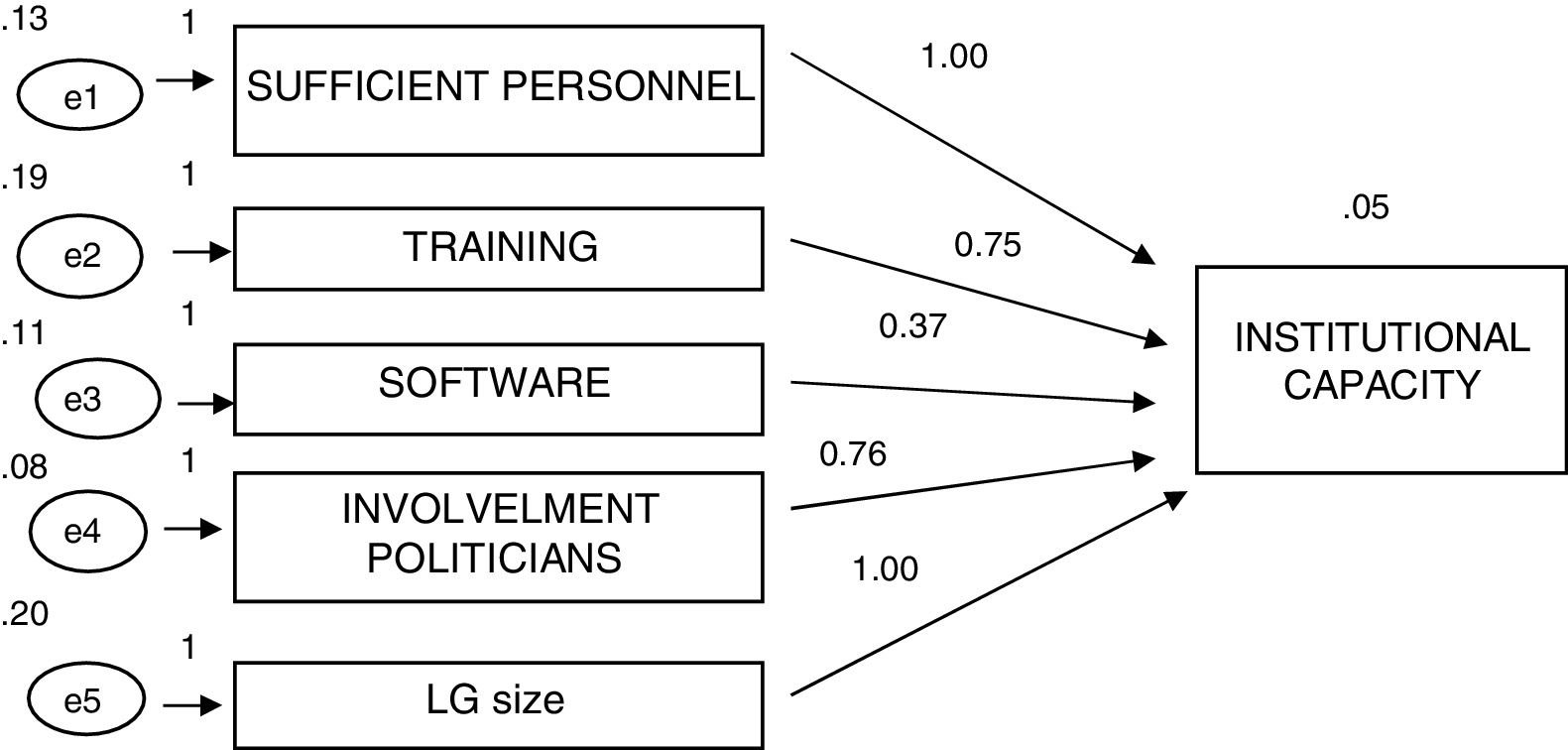

The global fit of the model is significant (Chi-squared=6.752 and p-value=0.240, over 0.05).3

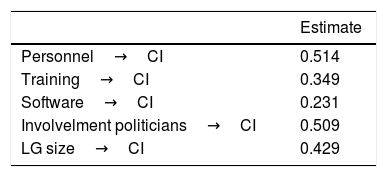

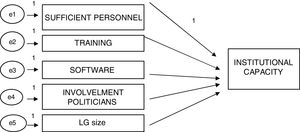

On the other hand, we have carried out non-standardized estimations of the model (see Fig. 3 and Table 6) and it has also been adjusted with standardized estimations (see Fig. 4 and Table 7).

Taking into account the demographic profile of the sample, it is noted that 54% of the answers come from LGs whose population is less than 5000 inhabitants. Therefore, for the analysis of the data we have decided to group the answers into two groups: small LGs (<5000 inhabitants) and large LGs (>5000 inhabitants).

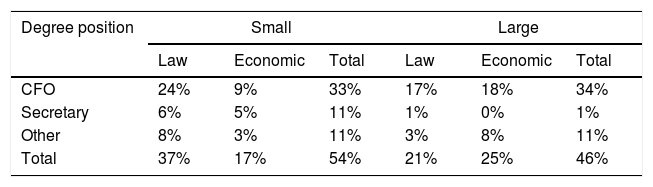

Analysis of the resultsAs to the professional profile of the respondents, almost 67% of them are in charge of CFOs and are mostly law graduates (barely 42% are graduates in Economics or Political Administration). The profiles of the ten people interviewed are almost identical in that they are law graduates and have been financial controllers for a minimum of 10 years (Table 3).

Three variables have been taken into account to measure the IC: human resources, training and technical resources (software). In this section we first carry out a description of the answers obtained in the questionnaires and in the interviews and, second, based on the conditions established in the methodology, we answer the research questions.

Human resourcesVarious authors (Alonso, 2007; Duque, 2012; Evans, 1996; Oslak & Orellana, 2001; Repetto, 2007; Tobelem, 1992) indicate having available the appropriate number of people as a necessary condition to achieve the institutional capacity.

Regarding the number of people who are part of the intervention area, 78% of the cases confirmed the lack of human resources to be able to successfully undertake the implementation of the accounting reform. It must be emphasized how in the small LGs, 87% consider that the personnel resources available are insufficient; this percentage drops to 54% in the larger LGs.

In the semi-structured interviews, it was stated that the work load had multiplied in recent years as a consequence of applying the Budgetary Stability Law (2012), the Transparency Law (2013) and the information demands required by the European System of Accounts (SEC2010).

TrainingThe human factor obviously does not only have a quantitative component but also one that is qualitative (Duque, 2012). This refers to education – both what the workers themselves have and that which they specifically obtain about the accounting reform. The adoption of new accounting standard requires training (PwC, 2014). Regarding the activities carried out to raise the degree of knowledge about the standard and due to the imminent entry into force of the new AI, a general increase of interest shown by those in charge of the financial control of Spanish LGs was noted. 72% state that they have received some kind of training. Those who have not had training are mainly (95%) from small LGs.

In most cases this training has been due to the initiative and convening power of the provincial councils and to COSITAL. Few initiatives have come at the request of the LG itself.

The training has mainly been courses (80%). Some were over 20h (35%), others between 10 and 20h (25%) and others less than 10h (15%). Most of them were theoretical presentations by teachers with some practical examples.

Technical resources (software)In the age of information and electronic administration, all the process of developing a LG's accountability is computerized. This is why one of the key variables in order to guarantee success when implementing a new standard is to have a computer application adapted to the new framework (Oslak, 2004; PwC, 2014). In this instance, in 27% of the cases it has been completely adapted and in 59% of them it is being adapted. Given the application's new configuration and the conceptual changes introduced by the AI, making a technical consulting service available for the financial controllers to solve whatever doubts and problems which may arise when putting it into practice seems obvious. Nevertheless, the respondents also mention problems linked to adapting the computer application.

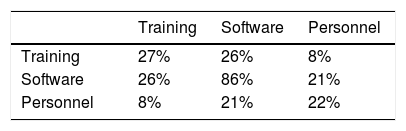

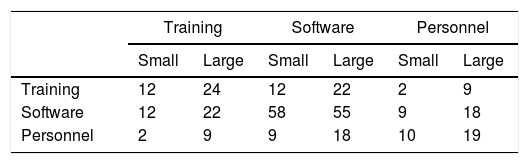

Taking into account the answers obtained and the conditions established in previous sections to consider that, in January 2015, each of the requirements has been complied with, it is noted that, in an individualized manner, the requirement which is broadly complied with by the LGs is having available the software (86%). However, the training necessary only reaches 27% and has sufficient human resources only in 22% (see Table 4).

As to the LGs which manage to affirmatively answer the three questions, only 10 do so, hardly 7.63% of the sample.

Linking these data with the size (see Table 5), it is noted that both the availability of personnel and training are conditioned by the size of the LG. Furthermore, in both cases a positive relation is seen between size and complying with the requirement (a greater degree of compliance is concentrated in the larger LGs). Yet the data show that in the development of the computer application the size of the LG does not condition the results. For the large LGs the application has already been developed in 95% of the cases and in 84% of those which have a smaller population. One of the reasons which explains this situation is that the small LGs, although they do not have the economic resources in their budget they do have the support of the County Councils.

Lastly, those LGs which have managed to attain an acceptable degree of development of the AI have been mainly – 80% – large LGs (see Table 5).

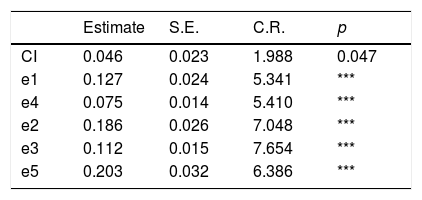

These results are consistent with the perceptions that the CFOs have expressed in the personal interviews. In this sense, it is worth mentioning that almost all the respondents make it clear that the key variables which will condition the development of institutional/administrative capacity to apply the new AI are, among others, (see Table 9): having enough staff, their training, the knowledge of the standard and their involvement in the process de elaborating the standard, as well as the availability of technical resources and the collaboration of the County councils and the General Intervention of the State Administration are the main factors identified.

In the personal interviews, of all these variables, the extreme importance of having a good IT solution was stressed. In this regard, one of the people interviewed pointed out that “if the IT program works, there won’t be problems, and applying the standard will be a success”.

In spite of what has been noted, the CFOs consider that when initially applying the AI these conditions do not exist, given that an excessive current workload stemming from the lack of technical and human resources and time; the shortage of training and, therefore, of knowledge; the standard's complexity and not having an up-to-date computer application sufficiently in advance in order to get familiarized with it.

They show relatively low levels of satisfaction about the training received, both concerning its usefulness to understand and learn the standard, and about the material received and the length of the different training schemes. In fact, some financial controllers indicated in the interviews that to cover these gaps they have informally created a network of colleagues of LGs from all parts of the country which enables them to share course materials that some of them have obtained, raise doubts and solve problems.

As to the standard's content, the perception is that the new standard's framework is very complex, that it does not consider the specificities of small LGs and that it does not link its economic concepts with its legal concepts. Thus, in the design and implementation of a new accounting system the organizational actors involved are influenced by past routines (Carpenter & Feroz, 2001). This represents the configuration of power relationships. If the new system means an important change in the standards, differing from the existing values, resistance to change is guaranteed (Burns & Scapens, 2000; Ter Bogt & Van Helden, 2000; Reginato, Fadda, & Pavan, 2010). In this sense, the respondents and those interviewed have not felt themselves to be active participants in the reform process. This has been carried out through a top-down model which has not counted on their opinions, though they are the main group/stakeholders affected by it.

Yet there is moreover a generalized feeling that they have not been properly informed of the reasons for and the advantages of the change, and about the problems that they may come across. Also, ignorance of the standard's content has had a negative impact on the understanding of the reform's values and aims. This has conditioned the expectations about the usefulness of the new accounting system and, in the end, its application and success (Harun & Kamase, 2012). All this leads them to be rather skeptical about the usefulness and the success of implementing the new standard – on a 0–5 scale, the average of their responses is about 2.6 points.

There is evidence in the personal interviews that the financial control staff feel discouraged about the usefulness of the accounting information for stakeholders, specifically for politicians. Thus, they state that “when after all the work done, the annual accounts are submitted for analysis and approval, either to the City Council or to the special accounts commissions, they will only look at the budgetary information, neglecting what has to do with economics and assets. All this leads us to wonder why so much reform, so much effort and work if, in the end, it's useless, at least at the municipal level”.

Unlike other cases, such as that of Italy (Salvatore & Del Gesso, 2013), the absence of a period of adaptation and of a pilot project which would have enabled the detecting of flaws and the standard to be improved has been noted. It is observed how all these problems are more relevant for the LGs which have a lower population.

Institutional capacity depends not only on administrative capacity, but also on the socio-political actors actively participating in the process and making timely decisions to favor the provision and adequacy of resources for the new needs (political capacity) (Rosas & Gil, 2013). Therefore, a key factor that conditions success of applying the accounting reform is the necessary collaboration between two working logics that cohabit in LGs – politicians and CFO – which in many cases have conflicting interests (Covaleski & Dirsmith, 1988; Duque, 2012; Harun & Kamase, 2012; Powell & DiMaggio, 1991; Pozzoli & Ranucci, 2013). So, regards the involvement of politicians, the results show that most politicians do not consider the accounting reform to be an interesting topic. 92.37% have not even been interested and/or have not been involved. There are no significant differences by size of the LG. Yet politicians are the ones who draw up the budget and, for that matter, the budgetary provision to finance the training of personnel and the availability of means. In this respect, those interviewed point out that they have continuously had a negative response from political decision makers to the financial controllers’ calls for funds to cover the costs of training and increasing the workforce. This is why one person interviewed indicated to us that “when we have to spend so much time and effort, often without support or backing, we feel the loneliness of the long-distance runner”. In this sense, these results are even more disappointing than those obtained by Reginato et al. (2010) in the case of the accounting reform of Italian LGs, which put this lack of involvement at 72%.

The results obtained highlight a positive relation between the independent variables identified in the model and institutional capacity (see Table 6). Of all of them, it is the size of the LG which has the least significance. On the other hand, as to the relevance of each of the variables to achieve IC (see Table 7), in first place, with an almost equal weight, are the number of people who will work in the application of the AI and the involvement of the politicians. Meanwhile, the availability of the software is relegated to the last place (Table 8).

Regression weights.

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel→CI | 1.000 | |||

| Training→CI | 0.752 | 0.328 | 2.292 | 0.022** |

| Software→CI | 0.373 | 0.217 | 1.720 | 0.085** |

| Involvelment politicians→CI | 0.759 | 0.291 | 2.612 | 0.009** |

| LG size→CI | 1.000 | 0.395 | 2.534 | 0.011* |

Note: Asterisks denote statistical significance * for p-value <0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

Key success variables (*).

| Values | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of the standard and training activities | 55 | 29 |

| Availability of sufficient and involved personnel | 34 | 18 |

| DK/DA | 27 | 14 |

| Availability of technical means and IT assessment | 25 | 13 |

| Active role of the County Council and the IGAE | 18 | 9 |

| Availability of enough time | 11 | 6 |

| Simplicity in the norm, especially for small municipalities | 10 | 5 |

| None | 4 | 2 |

| Teamwork and coordination between areas | 3 | 2 |

| Others | 3 | 2 |

| Total | 190 | 100 |

Note: (*) more than one option can be chosen.

The reform process of the accounting system of the Spanish public sector's local authorities has been analyzed. The adoption of new accounting standard require resources -investments in information technology systems and training- and political support (PwC, 2014). These factors determine the institutional capacity in both its administrative and political aspects (Oslak, 2004).

This study's aim is to determine if the LGs have managed to develop the institutional capacity required to successfully implement the new AI before January 1st, 2015.

The findings may provide a basis for other countries, in general, and for the countries of the European Union particular, in the process of public sector accounting reform, to attempt to override the negative effects and enhance the positive factors identified in the study. Moreover, this work has verified the influence of the variables analyzed in the literature in the achievement of institutional capacity in Spanish LGs. The model proposed, having been tested and validated, may serve as a reference for further research.

As in previous reforms, there has been a significant time lapse of 5 years in this one between the adopting of the PAS and the AI applicable to LGs. The changes and the novelties introduced are significant, meaning an alteration of the existing routines. In spite of this, unlike other cases, such as that of Italy (Salvatore & Del Gesso, 2013), in the Spanish case a top-down process has been followed, pilot experiences to detect problems have not been developed, nor has the active participation of the financial controllers been counted on in the standard's elaboration committees, nor have important actions been taken and implemented to develop the necessary institutional capacity.

Among the factors which determine this institutional capacity in both its administrative and political aspects, and in line with Oslak's (2004) conception, the quantity of human resources, the training received concerning the new standard and the availability of the computer resources must be highlighted.

As to the quantity of human resources, the need to increase the number of people who work in the financial control area has been apparent, especially in the small LGs. The results show that it is the main determinant variable of IC. On the other hand, the ability of the human factor is one of the most relevant variables which determine an organization's administrative capacity at the micro and meso levels (Duque, 2012). This ability is developed through the knowledge and training received about the new AI. In the Spanish case, the level of training received before the coming into force of the AI has been poor – and worse in the small LGs – both in the length of the courses and their contents. The model has highlighted that of the five variables considered as determinants of IC, training is in third place.

The results show that the variable software is the one which has the least relevance in building IC, which contrasts with the opinion given by the CFOs in the personal interviews.

Institutional capacity refers both to administrative capacity and political capacity. This is achieved when socio-political actors actively participate in the process and making timely decisions to favor the provision and adequacy of resources for the new needs (Rosas & Gil, 2013). This study has revealed a low participation and involvement of politicians in the process of developing institutional capacity and adopting measures which contribute to it, in spite of its having been shown that this is, along with the availability of personnel, the factor which most contributes to achieving IC.

Taking this into account, the results obtained bring to light that at the date of the obligatory application of the AI the LGs had only managed to have in place the software. However, they do not have enough personnel or the current workers have not received the training necessary to understand and know the content of the new AI. It is therefore concluded that the LGs did not attain the necessary institutional capacity and will have to continue allocating resources and time to improve it.

Taking this into account, the results coincide with those of Harun and Kamase (2012), as the gap between “accounting reform” and the deficient institutional capacity is considerable. When adapting a new accounting system, the policies have failed to recognize or identify the shortage of trained personnel and the existence of problems in its implementation. To sum up, a lack of interest and promptness has been observed both in terms of training and the new standard's implementation.

Lastly, given that an important number of factors play a decisive role in the process of implementing an accounting change in LGs, that this is not only a technical matter (Ter Bogt & Van Helden, 2000) and that these factors can determine the institutional capacity (Harun & Kamase, 2012), the degree of success of applying the accounting reform will be analyzed in later studies.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors are grateful to María Dolores Pérez Hidalgo for her comments.

In Spain there are different territorial administrations: the general government administration; the administration of autonomous communities; and that of local authorities.