This paper examines the attitudes and perceptions of business and accounting students toward corporate social responsibility and sustainability and what are the main variables for explaining differences in such attitudes and perceptions. Secondly, we compare the results of our study with those of the previous literature to determine whether there are differences depending on cultural, socioeconomic and legal forces. To accomplish this task, a survey was administered to be fulfilled by Spanish business and accounting students. In total, we received 319 surveys duly responded. Our results show that business and accounting students surveyed in our research have manifested a greater concern for the social and environmental dimensions of the corporate social responsibility and sustainability term. Meanwhile students surveyed in previous studies showed a strong commitment to the economic dimension of the corporate social responsibility and sustainability concept. Such differences are supported by cultural, socioeconomic and legal forces as well as by the institutional commitment of the university.

Este artículo analiza las actitudes y percepciones de los alumnos de la rama empresarial y contable frente a la responsabilidad social corporativa y la sostenibilidad, y cuáles son las principales variables para explicar las diferencias en dichas actitudes y percepciones. Además, los resultados de este estudio se comparan con la bibliografía previa para establecer la influencia de factores culturales, legales y socioeconómicos en relación con la percepción de los alumnos. Para ello se administró una encuesta para ser cumplimentada por alumnos españoles del ámbito empresarial y contable. En total se recibieron 319 encuestas bien cumplimentadas. Los resultados del trabajo muestran que los alumnos encuestados en nuestro estudio mostraron mayor preocupación por los problemas sociales y medioambientales, mientras que los alumnos encuestados en estudios previos mostraron mayor preocupación por la dimensión económica de la responsabilidad social corporativa y la sostenibilidad. Estas diferencias pueden explicarse por factores culturales, socioeconómicos y legales, así como por el compromiso institucional de la universidad.

The proliferation of business scandals and bad management practices leading to a global financial crisis has called the attention to what is the role of business and accounting education in relation to the unethical conduct of corporate managers (Burchell, Murray, & Kennedy, 2015; Godemann, Haertle, Herzig, & Moon, 2014; Larrán, Andrades, & Muriel, 2015). Some researchers, such as Pfeffer and Fong (2004), have criticized business schools because management education has been traditionally structured toward emphasizing profit maximization. Ghoshal (2005), cited in Lämsä, Vehkapera, Puttonen, and Pesonen (2008, p. 45) sees “a problem with business schools in that they teach theories and models which emphasize shareholder value and the idea that firms need to compete not only with their competitors but also with their own stakeholders, such as their employees, customers, and suppliers”.

In this regard, some authors have pointed out that business schools should adopt a pivotal role on CSR and sustainability (CSRS) education because such institutions are responsible to produce future managers who have to act in a socially and ethically responsible way to avoid business leaders’ failings (Alonso-Almeida, Casani, & Rodríguez, 2015; Godemann et al., 2014). As a consequence, there has been an increasing concern for incorporating CSRS themes into the business and accounting curricula in recent years, either alone or embedded across different courses (Christensen, Peirce, Hartman, Hoffman, & Carrier, 2007; Navarro, 2008; Wright & Bennett, 2011).

This increased concern about the role of business schools on CSRS education has been discussed in the academic literature and different studies have been conducted to analyze the attitudes and perceptions1 of business students toward CSRS (Kolodinsky, Madden, Zisk, & Henkel, 2010). Some papers have been focused on CSR and ethics perception by business students (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Eweje & Brunton, 2010; Lämsä et al., 2008) while other researchers have analyzed attitudes and perceptions of students on sustainability (Emmanuel and Adams, 2011; Kagawa, 2007; Nejati & Nejati, 2013; Watson, Lozano, Noyes, & Rodgers, 2013). In spite of this, few papers to date have analyzed attitudes and perceptions of students toward CSR and sustainability in aggregate (Deutsch & Berenyi, 2016). Taking into the account the Spanish case, excepting some examples (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015), there is a lack of empirical studies that has examined CSRS perception of business students.

In view of the previous comments, the present paper examines the attitudes and perceptions of business (management and accounting) students toward CSRS in a Spanish public university as well as the main variables for explaining differences in such attitudes and perceptions. To accomplish this task, a survey was administered to be fulfilled by Spanish business students. In total, we received 319 surveys duly responded.

Unlike other studies, the main contribution of this research is the comparison of our results with the findings of the previous literature to determine whether the opinion of business and accounting students toward CSRS is affected by legal, socioeconomic and cultural forces. The rationale of this paper is justified by the following arguments: first, the literature has shown that university students’ perceptions represent a good indicator of their future academic and professional outcome (Del Campo, Navallas, & Camacho-Miñano, 2016; Lizzio, Wilson, & Simons, 2002). Therefore, the opinion of business and accounting students toward CSRS could be indicative of their future professional conduct; secondly, this paper focuses on discussing the attitudes and perceptions of business and accounting students toward CSRS in aggregate whereas the academic literature has examined it separately. For the purposes of our study, we have based on the paper by Montiel (2008) who stated that CSR and sustainability are converging topics and both concepts share environmental and social concerns; third, we have chosen the Spanish case because there is a lack of empirical research on this field excepting some cases (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015). Also, Spain is a major example of unethical conduct (corruption political and restructuring of financial system) as well as it has been reported that Spain is the leading country in environmental infractions in Europe (Fajardo, Fuentes, Ramos, & Verdu, 2015).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The second section provides a review of the literature. The research methodology adopted is described in the third section. The fourth section explains and analyses the results followed by the discussion and the implications for practice. Finally, the last section suggests the limitations and suggestions for further research.

Literature reviewTheoretical backgroundMany papers have reviewed the literature about the theoretical contributions to the definition of the CSR and sustainability term (Dahlsrud, 2008; Montiel, 2008; Orlitzky, Siegel, & Waldman, 2011). Such studies found that the multitude of definitions on CSR and sustainability creates confusion, uncertainty and inconsistencies in regards to how we can conceptualize such terms and concepts.

Regarding the concept of CSR, Carroll contributions’ (1979, 1999) are the most commonly referenced to define this term (Dahlsrud, 2008; Montiel, 2008). Such studies configured the CSR term as “the social responsibility of business encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time” (Carroll, 1979; p. 500, cited in Montiel, 2008; p. 252). Concerning the concept of sustainability, its starting point comes from the definition of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) on sustainable development in its 1987 report, known as “Our Common Future” (Montiel, 2008). In this report it is noted that sustainable development “is the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987; p. 43, cited in Montiel, 2008; p. 254). Since then, the definition of the sustainability concept has been linked to the argument that development should be sustainable, implying the satisfaction of economic, environmental and social aspects, also recognized under the triple bottom line approach (Bansal, 2005; Dahlsrud, 2008; Elkington, 1997).

Nowadays, there is a group of academics who point out that CSR and sustainability are converging terms (Montiel, 2008; Orlitzky et al., 2011). Montiel (2008) revealed in his review paper that both terms have similar perspectives concerning how the future should be configured and this is associated with the need to balance economic responsibilities with social and environmental aspects. Dahlsrud (2008) argued that a more in depth explanation of the CSR term requires combining social and environmental dimensions. So, the definition of CSR integrating the economic, social and environmental dimensions (Van Marrewijk, 2003) is inextricably linked to the triple bottom line perspective on the sustainability concept (Elkington, 1997) which suggests that both terms are converging (Montiel, 2008).

Adopting an institutional approach, many international policy documents to incentive the incorporation of CSRS in university education have been approved in the last years. Among other initiatives, we can cite the Principles for Responsible Management Education approved by the United Nations Global Compact in 2007. Its mission is to transform management education by means of socially responsible and sustainable principles to be adopted into business schools (Burchell et al., 2015). Another important declaration is the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD), officially approved for the period 2005–2014, and whose mission aims to emphasize that education must be a fundamental pillar for achieving sustainable development. In research, we can point several theoretical studies in regards to the incorporation of sustainability in universities, such as the paper by Lozano, Lukman, Lozano, Huisingh, and Lambrechts (2013) that examined eleven declarations for improving the context of education for sustainable development in universities.

Attitudes and perceptions of students toward CSRSThere is a vast body of empirical research that has discussed attitudes and perceptions of students toward CSRS which can be classified in two different groups (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Eweje & Brunton, 2010; Nejati & Nejati, 2013; Watson et al., 2013). One group consists of papers that examined the attitudes and perceptions of business students toward ethics and CSR and the potential variables for explaining differences in such perceptions and attitudes (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Elias, 2004; Eweje & Brunton, 2010; Lämsä et al., 2008). The second group of papers analyzed attitudes and perceptions of university students toward sustainability themes (Emanuel & Adams, 2011; Kagawa, 2007; Nejati & Nejati, 2013; Watson et al., 2013).

We can find some differences between both groups of papers; firstly, studies on ethics and CSR issues are based on examining perceptions of business students while studies on sustainability are addressed to analyze whole population of university students, excepting the paper by Watson et al. (2013) which was focused on engineering students; secondly, the first group of papers discusses the implications of stakeholder versus shareholder theory while the second group of studies is built on the triple bottom line approach; third, the first group examines the influence of certain variables for explaining some differences in perceptions and attitudes while the second group is more connected with the exploratory analysis of students’ perceptions. Except in some cases (Kagawa, 2007; Tuncer, 2008), the literature that examines attitudes and perceptions of students toward sustainability describes the demographic profile of the sample (age, gender or academic level variables) but it is not analyzed whether these variables explain differences in such attitudes and perceptions.

Focusing on the Spanish context, few studies to date have been carried out to examine business and accounting students’ perceptions in regards to CSRS. One of the most relevant contributions is the paper by Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015). They examined the attitudes and perceptions of undergraduate students of Business and Tourism degrees of a public university of Madrid toward CSR. They found that students were more concerned with the idea that companies are multi-objective institutions in which they have to satisfy needs of a broad number of stakeholders. Our paper, unlike that the study of Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015), aims to contribute to determining how legal, cultural and socioeconomic aspects can affect the opinion of business students toward CSRS. Likewise, our sample consists of students of management and accounting degrees instead of tourism and management. Another difference is that our approach considers CSRS as an aggregate construct instead of separate terms.

Influential variables and development of hypothesesThis paper is built according to the variables more commonly analyzed in the literature on CSR and ethics perception in business students and less employed by scholars on their studies about perceptions and attitudes toward sustainability. In particular, the variables selected for this study have been gender, educational level, academic major, and work experience (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Eweje & Brunton, 2010; Kagawa, 2007).

The gender variable has been widely analyzed to explain whether there are differences on the perceptions and attitudes of students toward CSRS (Elias, 2004; Kagawa, 2007; Lämsä et al., 2008; Ng & Burke, 2010). International research on CSR and ethics found that female students were more concerned with social and ethical issues compared to their male colleagues. Elias (2004) pointed out that female students showed a greater orientation toward the positive association between CSR and profitability in comparison with male students. Similar conclusions were reached by Lämsä et al. (2008), in whose paper was found that women business students were more positively associated to ethical, environmental and social aspects than their male colleagues. In the Spanish context, Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015) found that female business students were more engaged toward CSR issues than their male counterparts. Research based on sustainability issues has documented mixed results. Tuncer (2008) found that female Turkish university students from a broad range of academic disciplines were more sensitive toward sustainability compared to their male colleagues. Similar findings were reached by Ng and Burke (2010), whose study found a strong association between women and practices on sustainability in business. Nevertheless, Kagawa (2007) found that men students from all academic disciplines in the University of Plymouth were more concerned with sustainability than female students. In view of most of the findings of the literature, we can infer that female students are more strongly concerned with CSRS than their men counterparts. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 1 Attitudes and perceptions of female business students are more positively associated toward CSRS than their male colleagues.

Another interesting variable is the age of the students. Empirically, several studies have found that older business students have a high appreciation of CSRS in comparison with younger ones (Adkins & Radtke, 2004; Luthar & Karri, 2005). The paper by Lämsä et al. (2008) found that older and upper-level students rated positively some aspects associated with the economic and social responsibilities of a company compared to entry-level students. Also, Eweje and Brunton (2010) found that age variable explained differences in perceptions and attitudes on CSRS issues. They pointed out that older students tended to be more ethical than younger students. In view of such comments, we expect that older business students show a greater concern for CSRS issues. Then, we propose the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 2 Attitudes and perceptions of upper-level business students are more positively associated toward CSRS compared to entry-level students.

Different papers have employed the academic discipline as a potential variable for explaining differences in attitudes and perceptions of students toward CSRS (Ibrahim, 2012; Kagawa, 2007). In the context of sustainability, Kagawa (2007) found that students from disciplines related to social science, business and science were more engaged with the sustainability term compared to other disciplines such as health, humanities and education. Within the business discipline, some researchers have found that management students perceived that ethics and CSR were more important for their training compared to the opinion of finance and accounting students (Cagle & Baucus, 2006; O’Leary and Hannah, 2008). This may be supported by the fact that finance and accounting discipline is based on the principle of shareholder wealth maximization, which implies a greater emphasis on the economic dimension of the CSR. In this way, the following hypothesis is proposed:Hypothesis 3 Attitudes and perceptions of management students are more positively associated toward CSRS than finance and accounting students.

Finally, many researchers have argued that the length of working experience of students could affect their attitude and perception toward CSRS (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Eweje & Brunton, 2010). However, the literature has found mixed results. Ng and Burke (2010) found no relationship between working experience and CSR attitude and perception in students. They stratified the sample as follows: students working full-time, students working part-time, and students not working at all. Elias (2004) found that, before the bankruptcies, students with less work experience were more likely to change their attitudes and perceptions toward CSR. On the other hand, some authors found that, once students have extensive professional experience, differences tend to disappear (Luthar & Karri, 2005). In view of the inconclusive results of the literature, we propose the following hypothesis2:Hypothesis 4 Having job experience is a significant factor in relation to differences in attitudes and perceptions of business students toward CSRS.

We employed an adapted version of the original Aspen Institute questionnaire which was first conducted in 2001 under the name “Where will they lead” (Aspen Institute, 2001) and subsequently was repeated in 2003 and 2007. The original questionnaire was prepared by the Aspen Institute's Initiative for Social Innovation through Business with the aim of measuring MBA students’ perceptions with regard to the roles and responsibilities that companies have in society. The first questionnaire was administered to MBA students of different international business schools, majority from United States, Canada and United Kingdom. In research, some authors have used an adapted version of this questionnaire to analyze the attitudes and perceptions of business students toward CSR (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Lämsä et al., 2008).

The adaptation process of the questionnaire was performed according to the following steps (Arsalani, Fallahi-Khoshknab, Ghaffari, Josephson, & Lagerstrom, 2011). First, an expert panel method was employed to choose the questionnaire. This expert panel was composed by the three researchers of this paper and its main decision was to select the most appropriate instrument to be used according to the theoretical motivation of this study. For such reason, we assumed that the adaptation of the original version of the Aspen Institute questionnaire could be adequate. The reason is that the population to be surveyed is composed of students with similar CSRS knowledge that students surveyed in the prior literature that used this questionnaire. The second step was to translate the original Aspen Institute questionnaire from English to Spanish and this was carried out according to the method followed by previous researchers (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Harkness, 2003; Lämsä et al., 2008). As Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015, p. 6) noted, the adaptation of a “questionnaire previously developed in a foreign language is more time-saving than developing a brand new one”. The questionnaire was translated by one author of this research at the beginning of the design of the study. The first version of the translated questionnaire was reviewed in-depth by the other researchers to make corrections. The final version was accepted by all researchers after discussing about grammatical, technical and conceptual aspects in order to make the translation as clear as possible and without cultural ambiguities (Ferrer et al., 1996).

The selected and adapted instrument contained 21 items integrated in two main sections: (1) a first section dedicated to defining a well-run company, understood as a socially responsible and sustainable company and composed of 12 items; (2) a second section composed of 9 items and devoted to measure the primary responsibilities of a company in society. The last section contained qualitative information in which students filled in their personal profile. The responses to each item were recorded on a 10-point Likert scale (rating scales: 1=strongly disagree, 10=totally agree). Likert scales consist of close-ended questions which allow respondents to reflect how much they agree or disagree with a particular item (Dillman, 2000). Many studies that have examined attitudes and perceptions of students toward CSRS have been carried out through questionnaires based on Likert scales (Eweje & Brunton, 2010; Watson et al., 2013). Netemeyer, Bearden, and Sharma (2003) pointed out that one of the main advantages of Likert scales in comparison with dichotomous scales is that they tend to create more scale variance.

The third and final step was to perform a reliability analysis of the adapted instrument (Gallardo & Sanchez, 2014; Larrán, Herrera, Calzado, & Andrades, 2015). To do this, we used the homogeneity index of each item (Barbero, Vila, & Suárez, 2006; Lacave, Molina, Fernández, & Redondo, 2015). This index reveals the extent to which each item measures the same of the global instrument and it contributes to the internal consistency of the test (Barbero et al., 2006). The literature states that items with low homogeneity index (less than 0.2) can be removed from the instrument (Lacave et al., 2015). The homogeneity index (not reported in the text) of each item presented values above 0.20 which reflects that the instrument was reliable. Also, we performed the Cronbach's alpha to determine if the items were measuring the instrument in which they were integrated (Gallardo & Sanchez, 2014). In accordance with the literature, it is expected that an instrument is reliable when the value of Cronbach's alpha is higher than 0.7 (George & Mallery, 2003; Nunally, 1978). In our case, for the two measures in which was divided the questionnaire, the Cronbach's alpha presented values above 0.80 confirming their internal consistency.

Data collection processThe adapted version of the original Aspen Institute questionnaire was distributed to business students enrolled in the two undergraduate degrees offered by the Faculty of Economics and Business of the University of Cadiz (Spain): Business Administration and Finance and Accounting. The process of data collection was carried out on a similar basis than the method followed by previous researchers (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Lämsä et al., 2008). Before starting the fulfillment of the questionnaire, the researchers made a brief explanation about the aims of the research and they asked the respondents if they understood the questions included in the questionnaire. None of the respondents manifested difficulties to understand the content of the questionnaire. Also, the researchers commented to the students that the data collected from their responses would be confidential and only used for purposes of research. After that, students started to fulfill the questionnaire. Regarding the process of data collection, the researchers followed the major principles associated with university ethical guidelines.

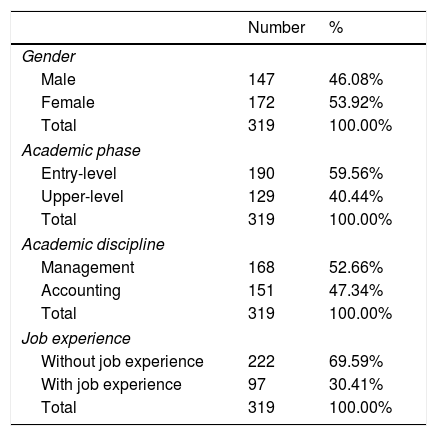

To obtain a comprehensive picture about the attitudes and perceptions of business and accounting students toward CSRS, the sample consisted of students in two different periods of their studies: entry-level and upper-level. This selection process has been widely used in the literature (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Eweje & Brunton, 2010; Lämsä et al., 2008). “Entry-level” consisted of students that were studying for the first year of their undergraduate degree while “Upper-level” consisted of all other students (Wong, Long, & Elankumaran, 2010). In addition, we have to point out that there was no student enrolled in a specific stand-alone course on CSRS. In sum, we received a total of 319 responses. Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the students who filled the questionnaire. Concerning the gender variable, the proportion of responses was quite similar with a slight higher participation of female students (53.92%). This pattern was similar in regards to the academic major variable in whose case the proportion of responses was slightly higher for students enrolled in business and management degrees (52.66%). Regarding the other demographic variables, we received a greater proportion of questionnaires completed by entry-level students (59.56%) and students without job experience (69.59%).

Demographic profile of the sample.

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 147 | 46.08% |

| Female | 172 | 53.92% |

| Total | 319 | 100.00% |

| Academic phase | ||

| Entry-level | 190 | 59.56% |

| Upper-level | 129 | 40.44% |

| Total | 319 | 100.00% |

| Academic discipline | ||

| Management | 168 | 52.66% |

| Accounting | 151 | 47.34% |

| Total | 319 | 100.00% |

| Job experience | ||

| Without job experience | 222 | 69.59% |

| With job experience | 97 | 30.41% |

| Total | 319 | 100.00% |

The data were collected during the period from May to September 2015. Due to the short period of time to collect the data, we assumed that responses would not be affected by variables which may change over time. Once the respondents completed the questionnaire on an anonymous way, the data were coded in an Excel database and then the data were processed statistically using the software SPSS v.19, property of IBM (New York, USA).

Statistical data treatment and measuresIn first place, we conducted the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test. Results showed that all variables were not based on a normal population (not reported). For such reason, we performed a logit regression model whose statistical method is characterized because the dependent variable is categorical (Dayton, 1992). For our study, the dependent variable was measured as the mean value (arithmetic mean) of each of the two constructs that make up the instrument: a well-run company and primary responsibilities of a company in society. This was calculated as the sum of the values rated by all students surveyed divided by the total of items that integrate each measure (12 and 9 respectively) multiplied by the total of responses received (319). After that, we categorized the dependent variable in the following way: 1 when for each case the mean value of each student is greater than the overall mean value and 0 otherwise. The independent variables were coded as follows: gender (0 men and 1 women), academic phase (0 entry-level students, 1 upper-level students), academic discipline (0 business and management undergraduate degree, 1 finance and accounting undergraduate degree), and job experience (0 students without job experience, 1 students with job experience).

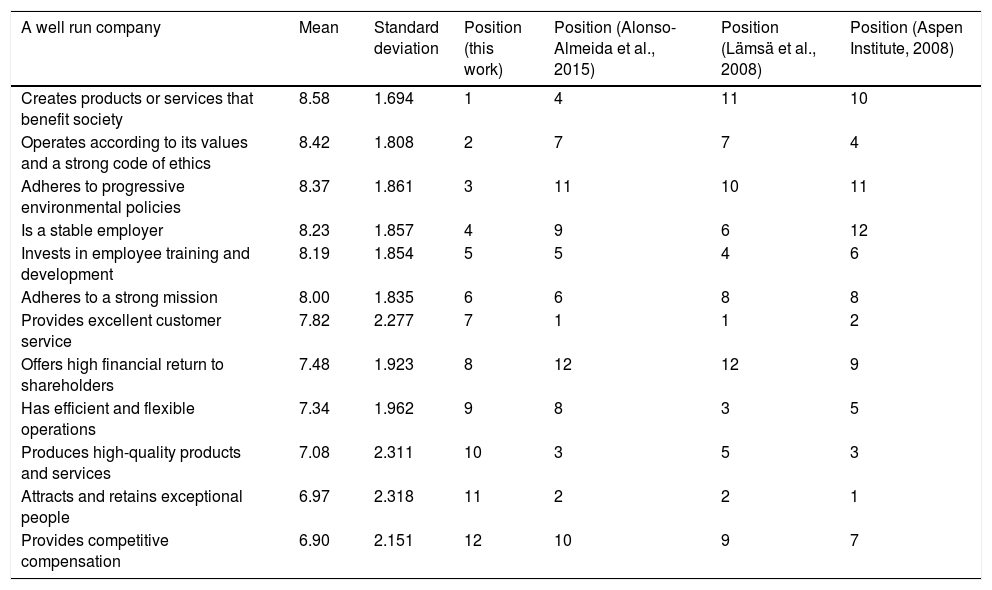

ResultsDescriptive analysisTable 2 shows the attitudes and perceptions of management and accounting students who filled the questionnaire concerning how they set up a well-run company. Firstly, all the items have been assessed over the median value (5) of the ten-point scale and standard deviation values have been relatively low (less than 2.5), which suggests that the responses have had little variability. In more detail, all the items have received a score between 6.90 and 8.58 and this could suggest that management and accounting students have showed a strong concern about CSRS issues of companies. In top positions, the three most important aspects of a well-run company for students surveyed are: (1) creates products or services that benefit society, mean 8.58; (2) operates according to its values and a strong code of ethics, mean 8.42; (3) adheres to progressive environmental policies, mean 8.37. In last positions, the less important aspects of a well-run company for students who filled the questionnaire are: (10) produces high-quality products and services, mean 7.08; (11) attracts and retains exceptional people, mean 6.97; and (12) provides competitive compensation, mean 6.90.

Descriptive analysis of a well-run company: comparison with previous studies.

| A well run company | Mean | Standard deviation | Position (this work) | Position (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015) | Position (Lämsä et al., 2008) | Position (Aspen Institute, 2008) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creates products or services that benefit society | 8.58 | 1.694 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 10 |

| Operates according to its values and a strong code of ethics | 8.42 | 1.808 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 4 |

| Adheres to progressive environmental policies | 8.37 | 1.861 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 11 |

| Is a stable employer | 8.23 | 1.857 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 12 |

| Invests in employee training and development | 8.19 | 1.854 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| Adheres to a strong mission | 8.00 | 1.835 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Provides excellent customer service | 7.82 | 2.277 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Offers high financial return to shareholders | 7.48 | 1.923 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 9 |

| Has efficient and flexible operations | 7.34 | 1.962 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Produces high-quality products and services | 7.08 | 2.311 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Attracts and retains exceptional people | 6.97 | 2.318 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Provides competitive compensation | 6.90 | 2.151 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 7 |

Table 2 also compares the results of this study with those of the literature. While a direct comparison between studies cannot be made accurately due sample size and populations are different, this study provides a comparison with those papers whose data collection method was based on an adapted version from the original Aspen Institute questionnaire (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Aspen Institute, 2008; Lämsä et al., 2008). In this sense, we have to note that although there are not many differences in the mean values of each of the items in our paper (8.58–6.90), the main interest of this comparison is to establish a comparative ranking that allows extracting similarities or differences. Our approach is to provide an exploratory analysis of the data comparing with previous studies rather than deepen in explaining the differences in the mean values of each of the items. The paper by Lämsä et al. (2008) consisted of a sample of 217 students enrolled in master's degree in business at two Finnish universities. The survey was performed during the period from 2003 to 2006. Concerning the demographic profile of the sample, 53% of the questionnaires were filled by students beginning their master degree while 47% of the questionnaires were completed by students close to finishing their studies. There was a greater proportion of responses by women students (56%) and 33% of the questionnaires were filled by students without professional experience. In 2008, the Aspen Institute Center for Business Education went out to 15 business schools from United States to survey MBA students about their attitudes and perceptions toward issues in business and society. The demographic profile of the sample showed a greater proportion of responses of men students (65%) and responses of students who had started their master in MBA (55%), followed by students were halfway through the program (37%). Finally, the sample of Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015) consisted of students enrolled in Business Administration and Tourism degrees at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration of the Autonomous University of Madrid (Spain). These researchers performed their study in November 2010. The demographic profile of the sample showed a greater proportion of responses by women (65.2%), entry-level students (58.1%) and students with some kind of job experience (59.6%)

In view of the data contained in Table 2, we can appreciate important differences among these studies in relation to the responses ranked in top and down positions. Our findings show that management and accounting students have rated the item Adheres to progressive environmental policies (8.37) as the third most important aspect of a well-run company. Nevertheless, students surveyed in the other three studies rated this item in last positions. Secondly, our study reveals that management and accounting students have rated the item Creates products or services that benefit society (8.58) as the most important aspect of a well-run company. Also, this item received the fourth highest rating for students sampled in the paper by Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015). Conversely, students sampled in the Aspen Survey (2008) and by Lämsä et al. (2008) rated this item in last places. Third, our study show that management and accounting students have rated the item Operates according to its values and a strong code of ethics (8.42) as the second most relevant issue of a well-run company. Meanwhile, students sampled in the other papers rated this item in an intermediate position. On the other hand, we found that management and accounting students have rated the items Produces high-quality products and services (7.08) and Attracts and retains exceptional people (6.97) in down positions. Nevertheless, both items were rated by students sampled in the other studies in top positions. Similarly, in our study, the item Provides excellent customer service (7.82) is listed in the seventh place according to the attitudes and perceptions of management and accounting students. Meanwhile, this item was rated as one of the most important aspects of a well-run company by students sampled in the previous studies. In view of the previous comments, there are many important differences concerning the definition of a well-run company. Students sampled in our study are strongly concerned with environmental and social dimensions of the CSRS term while students who were sampled in the other studies were more positioned toward a view based on the economic responsibilities of a company, explained by their greater orientation toward customer and employees dimensions.

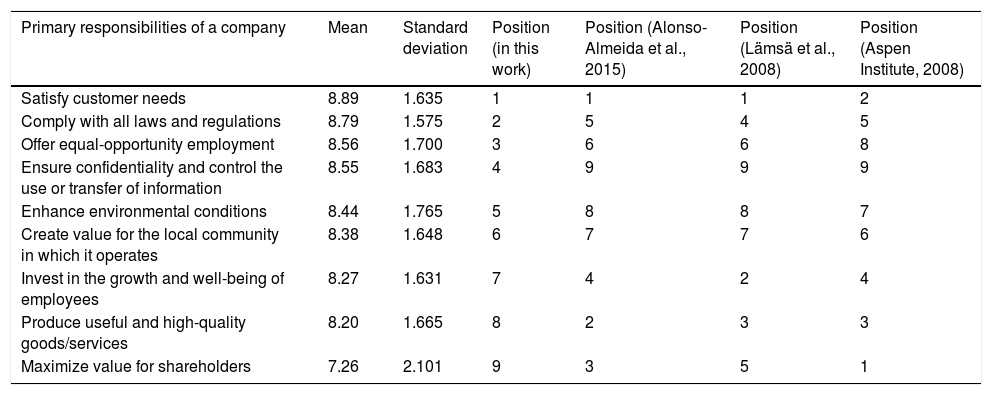

Focusing on the primary responsibilities of companies, Table 3 reveals that students have asserted that the top three responsibilities of a company are: Satisfy customer needs (mean 8.89), Comply with all laws and regulations (mean 8.79), and Offer equal-opportunity employment (mean 8.56). The mean values of all items are in a range between 7.26 and 8.89, which suggest that students have rated these items as relevant responsibilities and obligations of a company. In last positions, students sampled in our study have rated as the less important responsibilities of companies the following items: Invest in the growth and well-being of employees, mean 8.27; Produce useful and high-quality goods/services, mean 8.20; and Maximize value for shareholders, mean 7.26.

Descriptive analysis of primary responsibilities of a company: Comparison with previous studies.

| Primary responsibilities of a company | Mean | Standard deviation | Position (in this work) | Position (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015) | Position (Lämsä et al., 2008) | Position (Aspen Institute, 2008) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfy customer needs | 8.89 | 1.635 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Comply with all laws and regulations | 8.79 | 1.575 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Offer equal-opportunity employment | 8.56 | 1.700 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Ensure confidentiality and control the use or transfer of information | 8.55 | 1.683 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Enhance environmental conditions | 8.44 | 1.765 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Create value for the local community in which it operates | 8.38 | 1.648 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Invest in the growth and well-being of employees | 8.27 | 1.631 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Produce useful and high-quality goods/services | 8.20 | 1.665 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Maximize value for shareholders | 7.26 | 2.101 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

Comparatively, three of the four most important responsibilities rated by students sampled in our study received down marks by students surveyed in the other studies (excepting the item Satisfy customer needs). On the other hand, students sampled in our study have rated in last positions some items that received top marks by students sampled in the previous studies. Findings from this section reveal similar conclusions than in the analysis of a well-run company. Thus, management and accounting students sampled in our study are strongly concerned with corporate governance principles, such as accountability, transparency, complies and regulations. In another way, students sampled in our study have not showed a strong orientation toward the economic dimension of the CSRS term, which is oriented to maximize customer and shareholders needs.

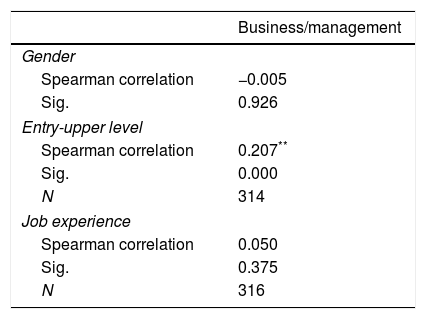

Statistical analysisTable 4 reports the Spearman correlation coefficients among our set of independent variables. We can appreciate that there is a statistical correlation at the 1% level among entry/upper level and business/management degree variables. Nevertheless, none of the variance inflation factors – not reported – exceed the critical value of 10. Thus, it can be said that multicollinearity is not a serious problem in the present study.

Spearman correlation coefficients.

| Business/management | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Spearman correlation | −0.005 |

| Sig. | 0.926 |

| Entry-upper level | |

| Spearman correlation | 0.207** |

| Sig. | 0.000 |

| N | 314 |

| Job experience | |

| Spearman correlation | 0.050 |

| Sig. | 0.375 |

| N | 316 |

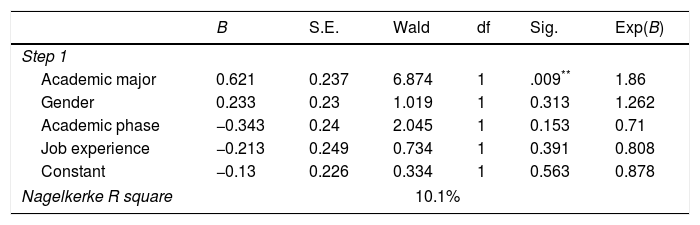

Tables 5 and 6 show the results of regressing the independent variables depending on the two logit models proposed. For the first model, which is focused on determining how the different independent variables can affect the definition of a well run company, results reveal that all variables explain only the 4.0% of the variation of the dependent variable. In spite of this, previous researchers obtained a low R square in their logit regression models (Larrán, Andrades, et al., 2015). Table 5 shows that the most influential variable for explaining the definition of a well run company is academic major. Contrary with our initial expectation, the positive standardized regression coefficient states that accounting and finance students are more strongly engaged with CSRS compared to business and management students. Taking into account the other variables, no statistically significant differences have been found to explain the commitment toward CSRS. Nevertheless, and according to gender variable, the positive coefficient shows that female students are more concerned with CSRS than their male colleagues. Likewise, and based on the negative standardized regression coefficient, we have found that entry-level students and students without job experience have a high appreciation of CSRS compared to others.

Logit regression results of a well run company.

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Academic major | 0.621 | 0.237 | 6.874 | 1 | .009** | 1.86 |

| Gender | 0.233 | 0.23 | 1.019 | 1 | 0.313 | 1.262 |

| Academic phase | −0.343 | 0.24 | 2.045 | 1 | 0.153 | 0.71 |

| Job experience | −0.213 | 0.249 | 0.734 | 1 | 0.391 | 0.808 |

| Constant | −0.13 | 0.226 | 0.334 | 1 | 0.563 | 0.878 |

| Nagelkerke R square | 10.1% | |||||

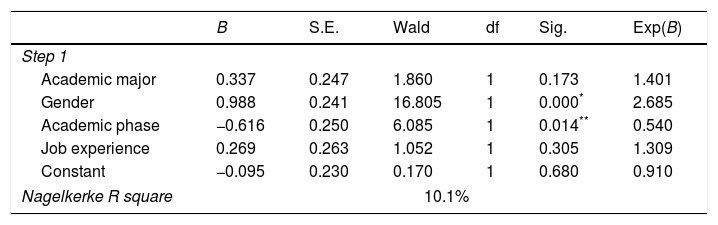

Logit regression results of primary responsibilities of a company.

Focusing on the second model, the independent variables explain the 10.1% of the variation of the primary responsibilities variable. Results contained in Table 6 allow us to appreciate that the most significant variables for explaining the primary responsibilities of a company in society are gender and academic phase. With regard to the gender variable, and consistent with our expectation, the positive standardized regression coefficient show that female students are more concerned with the commitment toward CSRS. In relation to the academic phase, the negative coefficient leads to point out that entry-level students have shown a strong concern for CSRS issues compared to their upper-level students. This statistical result is contrary with our expectation. The other independent variables have not been statistically significant for explaining whether such factors affect the commitment toward CSRS. In spite of this, the positive coefficient states that accounting and finance students have a high perception of CSRS as well as those students with job experience compared to others. In view of the above, we totally reject Hypotheses 2, 3 and 4 and Hypothesis 1 is partially supported.

Discussion and implications for future research and practiceResults show that, for Spanish business and accounting students surveyed, a well run company could be defined as one that manifests its social and environmental commitment as well as being transparent and accountable to society. Likewise, they stated that the main social responsibilities for a company are strongly associated with the need to satisfy the needs and expectations of stakeholders as well as to comply with regulations.

This seems to suggest that future Spanish business and accounting managers are better suited to the stakeholder theory than the shareholder approach. Benn et al., (2006, p. 157) made the following reflection: “How does Milton Friedman's statement of 30 years ago stand up today? One result of the breaking down of organizational barriers in contemporary conditions of the global economy is a new awareness by management that the firm needs to respond in ethical terms to both primary and secondary stakeholders”. These authors stated that corporations worldwide are suffering an important crisis in confidence and credibility and this implies the need to introduce some changes through the adoption of environmental and social practices. Based on the theoretical implications of this theory, the implementation of CSRS practices into the corporate strategy of companies requires identifying the expectations and needs of different stakeholders (Reverte, 2009; Rodríguez-Bolívar, Garde-Sánchez, & López-Hernández, 2015). In the same vein, Bansal (2005) pointed out that the creation of products or services that benefits to the society could help companies to build a sustainable competitive advantage over time.

Empirically, the findings have shown that gender, academic major and academic phase are the most influential variables associated with the attitudes and perceptions of Spanish business and accounting students toward CSRS. Results have revealed that accounting students have a high appreciation of what could be defined as a well-run company in comparison with their business and management colleagues. This is contrary to our expectation and this could be explained by the greater concern for the economic dimension of CSRS by accounting students. We also found that female students are more concerned with the social role of companies than their male counterparts. This is relevant for the Spanish context due to the general situation of women within senior management teams of enterprises. Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015), citing the data from the National Statistics Institute (2011), noted that only 33.27% of top managers in companies are women. This data could reveal that more women in top management positions could imply a greater CSRS engagement in organizations. Also, entry-level students have shown a greater concern for the role and responsibility of companies in society compared to upper-level students. Concerning the other variables, we have not found statistically significant differences for explaining attitudes and perceptions of students toward CSRS.

Another relevant contribution of this study is the presence of differences between our results and those of the academic literature in regards to the position of each item used to measure a well-run company and the primary responsibilities of companies. Comparatively, we have found that business and accounting students surveyed in our research have manifested a greater concern for the social and environmental dimensions of the CSRS, while students surveyed in previous studies showed a strong commitment to the economic dimension of the CSRS. Such differences are supported by cultural, socioeconomic and legal forces as well as the institutional leadership exerted by the university.

First, the cultural context could explain differences in attitudes and perceptions of what could be defined as corporate responsibility in society. In such case, our results have shown that Spanish students surveyed in our paper configured the item maximize value for shareholders as the less important social responsibility of a company. Meanwhile, US students surveyed in the Aspen Institute questionnaire (2008) appreciated this item as the main responsibility of a company in society. This could be in response to the fact that Spain, framed within the welfare society in Europe, has configured the stakeholder approach as the most relevant way of doing business while US is more favorable to the shareholder view (Lämsä et al., 2008). Different researchers have stated the presence of important cultural differences between the US and Europe (Moon & Orlitzky, 2011). In spite of sharing certain aspects in their economic systems, US is built on the origins of the liberal market economy while Europe is more associated with the features of the coordinated market economy (Moon & Orlitzky, 2011). Matten and Moon (2008) examined that the institutional framework of different countries could affect the orientation toward CSRS. They stated that (p. 408) “there is a much stronger American ethic of stewardship and of “giving back” to society…This contrasts with the greater European cultural reliance on representative organizations, be they political parties, unions, employers’ associations, or churches, and the state”.

The socioeconomic context is another factor that could explain differences in attitudes and perceptions of what could be configured as a well run company and the primary responsibilities of a company (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Kujala, 2010). Our questionnaire was administered in 2015 while the other studies were performed in the period from 2003–2010. The recent economic crisis, with more noticeable effects in the Spanish context, as well as the numerous and recent cases of frauds and corruptions in Spain have led to an increasing concern for accountability and corporate governance principles. Hence, the current socioeconomic context could explain the fact that Spanish business and accounting students have appreciated that a socially responsible and sustainable company has to be accountable to the society as well as has to implement environmental policies, create benefits to society and complying with regulations.

The legal framework could be added as a factor to explain differences in attitudes and perceptions of students toward CSRS (Matten & Moon, 2008). Taking a comparative view between the US and Europe, there has been a set of governmental initiatives aimed at fostering CSRS practices in Europe, which is understood as an implicit element of the institutional framework. Meanwhile, US is more favorable to applying explicit strategies of CSRS. In this regard, institutions such as the United Nations (UN), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the International Labor Organization (ILO), and the Global Reporting Initiative have developed different codified norms and regulations on the context of CSRS such as the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD), also known as “Rio+20 which derived in the Report of the UNCSD (Matten & Moon, 2008; United Nations, 2012). In addition to the current socio-economic context in Spain, there has been a legal enforcement to promote transparency and CSRS of public and private corporations (Reverte, 2015). Among such initiatives, the Spanish government created the Law 2/2011 on Sustainable Economy whose main aim was to incorporate structural reforms to create a sustainable economy (Spanish Parliament, 2011). In 2013, the Spanish government approved the Law 19/2013 on Transparency and Good Governance whose main goal is to require to public organizations to report about their institutional and economic affairs to ensure transparency (Spanish Parliament, 2013). One year later, the Spanish government approved another important regulation called “Spanish strategy on companies’ CSR practices 2014–2020” (Spanish Ministry of Employment and Social Security, 2014). The main goal of this Strategy is “to support the development of responsible practices in the public and private sectors in order that they become a significant driver of the country's competitiveness and its transformation towards a more productive, sustainable and inclusive society”.

Finally, another potential factor for explaining differences between the results of our study and those of the literature is the institutional commitment exerted by the University of Cadiz (Ferrer-Balas et al., 2008). The implementation of norms, rules, values resulting in mandatory and voluntary requirements for the University of Cadiz could lead to adopting CSRS from an implicit approach (Matten & Moon, 2008). In such regard, this university declared their environmental policy in 2006. This policy was guided by the DESD and by the Working Group on Environmental Quality and Sustainable Development set up by the Conference of Rectors of Spanish Universities (CRUE). Also, the University of Cadiz has published a total of seven sustainability reports (period from 2008 to 2014) in the GRI sustainability database which suggests their leading role in sustainability reporting. Adopting a view based on management, this university implemented its “Comprehensive Sustainability Plan” which allowed the certification of an “Environmental Management System”, obtaining certification UNE-EN ISO 14001:2004 in 2011. More recently, the University of Cadiz created the Office Vice Chancellor for Social Responsibility in 2013 whose aim is to respond to the proliferating public concern for a sustainable and socially responsible university. Also, the Faculty of Economics and Business is a signatory of the United Nations Global Compact, an initiative for organizations committed to aligning their operations with ten universally accepted principles in regards to environment, labor, anti-corruption and human rights.

This paper has some important implications and recommendations for practice. In view of the results, business and accounting students could be claiming a greater incorporation of CSRS themes into the university curricula in relation to how they perceive a well run company and what are their main responsibilities in society. Such attitudes and perceptions could be in response to the current socioeconomic context characterized by proliferating corruption cases and financial scandals which suggests a limited training on CSRS by business managers. In this regard, the academic literature has found that the extent to which business schools are offering CSRS education is still underdeveloped (Matten & Moon, 2004; Moon & Orlitzky, 2011; Setó-Pamies, Domingo-Vernis, & Rabassa-Figueras, 2011). Hence, business schools are called to expanding their training orientation toward ethical, social and environmental themes.

Another potential implication and recommendation for future is that university leaders and members of senior management teams have to be engaged with CSRS by signing declarations, implementing policies and strategies or by the creation of research networks on CSRS. This could help to build an institutional climate that incentives the integration of CSRS themes into different areas of the university, such as education. Different authors have revealed that the lack of support from senior managers of universities could hamper the incorporation of CSRS at universities (Ferrer-Balas et al., 2008; Velásquez et al., 2005).

Limitations and further researchAny paper has its limitations. The comparison with the literature has been made in a context in which the economic climate has changed and this has supposed the approval of new legislation on CSRS. Results could be biased by such differences in the socioeconomic context as well as the new legal framework. Therefore, future research could be addressed to perform a cross-cultural study to examine whether the attitudes and perceptions of business students toward CSRS is determined by cultural and legal aspects. Also, this study is not longitudinal so it would be interesting to make an overtime analysis taking as a reference the attitudes and perceptions of entry-level students who filled the questionnaire in this study. By means of surveying the same group of students in a period of several years, we would appreciate whether their attitudes and perceptions have changed. Another potential limitation of the study is that the questionnaire was only administered to business and accounting students that are enrolled in the Campus of Cadiz. The Faculty of Economics and Business also offer its business and management degree in Jerez and Algeciras. Therefore, it could be interesting to extend the scope of the paper to the other campuses to determine whether the geographical area is a potential explanatory factor. Likewise, the next step to the previous would be to expand this study to students from other academic disciplines of the University of Cadiz. In depth, it could be interesting to compare the attitudes and perceptions of students from business, science, and engineering toward CSRS.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

The literature uses both terms interchangeably to analyze the opinion and understanding of students toward CSR and sustainability.

Experience variable has been coded as job experience because our sample consists of undergraduate students and this could imply that they may have had any job but their working experience could be reduced.