Auditors’ professionalism has been criticized in recent years. Literature suggests that professionalism is decreasing due to the current audit market and the predominance of commercial goals.

ObjectivesThe main objective of this paper is to analyze auditors’ commitment to professionalism through two key professional values: public interest and independence enforcement. In addition, this study analyzes whether postgraduate students’ professional values differ from those of experienced auditors, and among auditors at different career stages. It also studies the influence of public interest commitment and independence enforcement on auditors’ ethical judgement.

MethodologyThe research methodology comprised a survey that was distributed among auditors as well as among students enrolled in a postgraduate degree in auditing.

122 responses from Spanish auditors and 55 responses from students in a postgraduate auditing course were obtained.

In order to test the hypothesis, ANOVA tests and a multiple regression analysis were conducted.

ResultsThe results of this paper reveal that students’ commitment to the public interest and independence enforcement was significantly higher than that of auditors, and that these professional values lowered as auditors gain experience. However, the findings also show that the auditors possess higher ethical judgement than students do. Further, the results reveal that these two values are predecessor of ethical judgement.

ConclusionThis study has practical implications for the improvement of ethical decision-making in auditing, as these results can assist with the proposal of measures that could apply to the education, recruitment, and professional development of auditors.

Los valores profesionales de los auditores han sido criticados en los últimos años. La bibliografía ha señalado que la profesionalidad de los auditores se ha reducido debido a la situación del mercado actual de la auditoría y al predominio de los objetivos comerciales frente a los profesionales.

ObjetivosEl objetivo principal de este artículo es analizar el compromiso de los auditores con la profesionalidad mediante dos valores profesionales fundamentales: el interés público y el compromiso con la independencia. Además, este artículo estudia si los valores profesionales de los estudiantes de posgrado de auditoría difieren de los valores de los auditores en ejercicio y si estos varían entre los auditores en diversos momentos de su carrera profesional. El estudio también pretende establecer la influencia del compromiso con el interés público y el compromiso con la independencia sobre el juicio ético de los auditores.

MetodologíaLa metodología utilizada consiste en una encuesta distribuida entre auditores en ejercicio y estudiantes de posgrado de auditoría. Se obtuvieron 122 respuestas de auditores españoles y 55 respuestas de estudiantes de posgrado de auditoría.

Para comprobar las hipótesis planteadas, se han llevado a cabo pruebas ANOVA y análisis de regresión múltiple.

ResultadosLos resultados de este artículo revelan que el compromiso con el interés público y con la independencia es mayor en el caso de los estudiantes que en el caso de los auditores. También muestran que estos valores profesionales se reducen con la experiencia. Sin embargo, los resultados también indican que los auditores poseen un juicio ético superior al de los estudiantes. Hay que destacar también que los resultados revelan que los valores profesionales en estudio, interés público e independencia, influyen considerablemente en el juicio ético.

ConclusionesEste estudio tiene implicaciones prácticas en la mejora de la toma de decisiones éticas en la auditoría de cuentas. Los resultados obtenidos pueden ayudar a la propuesta de medidas aplicables tanto en la educación como en la selección y desarrollo profesional de los auditores.

Audit failures associated with the corporate scandals of the beginning of the century, as well as the recent severe global financial crisis, have damaged the auditing profession's public image and confidence in its function. As some authors argue, audit firms’ culture has changed in recent years towards the increasing prioritization of business goals (Baker, 2014; Gendron, Suddaby, & Lam, 2006; Hanlon, 1996; Wyatt, 2004), although the idea of public interest is still formally displayed in the execution of their duties (Davenport & Dellaportas, 2009). As a result, audit failures have been attributed to a lack of professional identity and insufficient dedication to professional ideals on the part of auditors (Clikeman, Schwartz, & Lathan, 2001; Wyatt, 2004).

According to Samuel et al. (2009, p. 368) ‘trust in what accountants produce depends on the degree of trust in their person, and it is the professionalism of their conduct that engenders such trust’. The conception that an auditor forms about the profession to which he or she belongs and the implications of being part of it can influence the way in which he or she identifies, experiences, and responds to ethical dilemmas that are presented in the course of audit work (McPhail, 2006). Professionally committed accountants would be more responsible in advancing the profession's values, as well as in improving their own performance (Larson, 1977).

Although criticisms towards the profession are constant, few recent studies have addressed accountants’ professionalism (Bamber & Iyer, 2002). In this regard, some scholars (Carrington, Johansson, Johed, & Öhman, 2013; Suddaby, Gendron, & Lam, 2009) call for further research on the reasons why a shift from professional to commercial logic occurs in the accounting field. Suddaby et al. (2009) have tried to answer these questions by analysing the variation in professional values and attitudes across different practice areas and work contexts.

Most of the studies that have analyzed individuals’ professional commitment have measured commitment in terms of participation in, and attitude towards, professional institutions. These studies have not addressed the degree to which professional accountants accept and acknowledge the core professional values (Suddaby et al., 2009).

This study fills this gap in the literature by analysing auditors’ commitment to the accounting profession's central values. The study emphasizes the attitudinal characteristics of professionalism that influence accountants’ professional behaviour (Goetz, Morrow, & McElroy, 1991; Hall, 1968). It draws on ideas from the sociology of professions to explain the professional socialization that occurs in the auditing field. Accordingly, the present research focuses on key issues related to professionalism in the audit environment, such as public interest commitment and independence enforcement commitment.

Warren and Parker (2009) call for further research on the construction of the professional identity by younger professional accountants who are starting their careers. The accounting profession as well as academics have emphasized the need for accountants to develop professional values and internalize their professional responsibilities to society early in their careers, even before they enter the profession (Elias, 2006, 2008; Ferguson, Collison, Power, & Stevenson, 2011).

This study contributes to the accounting literature by studying the professional values of students in a postgraduate auditing course. In this sense, this study analyzes whether postgraduate students’ professional values differ from those of experienced auditors, and among auditors at different career stages.

The relationship between professional attitudes and the ethical decision-making process has been previously documented (Elias, 2006, 2008; Kaplan & Whitecotton, 2001; Lord & DeZoort, 2001). This paper studies the influence of public interest commitment and independence enforcement on auditors’ ethical judgement. At this respect, this research responds to calls from existing academic literature to analyze whether auditors’ commitment towards the public interest and independence enforcement are related to their ethical decisions (Alleyne, Hudaib, & Pike, 2013; Gendron et al., 2006; Suddaby et al., 2009).

The present research reveals, on one hand, that students’ commitment to the public interest and independence enforcement is significantly higher than auditors’ values. Moreover, these two professional values decrease as auditors gain experience. On the other hand, it reveals that auditors show higher ethical judgement than students do. Finally, the findings show the influence of public interest commitment and independence enforcement on ethical judgement.

The results of this study have important implications for professional organizations, audit firms, regulators, and universities. An analysis of the development of the professional's values along his or her career has practical contributions for the improvement of ethical decision-making in auditing. The results of this study were used to propose measures that could apply to the education, recruitment, and professional development of auditors.

Moreover, this research provides an understanding of the profile of future auditors and helps with the identification of gaps and deficiencies in their education and training. In order to enhance ethical behaviour, and consequently audit quality, one of the goals of the profession should be to attract the most talented members with respect to both technical expertise and professional values (Abdolmohammadi, Read, & Scarbrough, 2003; Cohen, Pant, & Sharp, 2001). This is necessary to improve the quality of audit services, as the values, ethics, and attitudes that these auditors exhibit when performing their activities are key elements of audit quality (IAASB, 2014).

Finally, this study broadens the knowledge of the accounting profession in institutional settings different to those commonly studied. In Spain, as in other code law countries, a high level of legalism characterizes professional regulation. The ethical guidelines in auditing have largely been stated through legal regulation, and are limited mainly to the provisions and incompatibilities regulated by law to preserve the auditor's independence.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the next section presents the background of the study and develops the hypotheses; the third section describes the research method; results are presented in the fourth section; and the final section provides the conclusions and limitations of the study and proposes directions for future research.

Theoretical background and hypothesesProfessional valuesThe discussion around professions and the professionalization process of different occupations has usually assumed that there are certain characteristics or attributes that are distinguishing features of professions. Some of the usually considered structural attributes of the professions include autonomous professional organization, specialist skills and knowledge, accreditation and a code of ethics (Cowton, 2009; Hall, 1968). According to Freidson (2001), these formal attributes establish the conditions by which it is possible to empirically determine whether a profession exists. However, at their root, other less tangible elements provide a basis for the institutions of professionalism. These elements are the claims, values, and ideas to which Freidson (2001) referred as ‘ideology’. Similarly, Hall (1968) claimed that, apart from the above-mentioned characteristics, professions also have some attitudinal attributes. According to the author, these attitudinal aspects reflect the manner in which professionals view their work, and are related to their behaviour. In this regard, there is a general agreement that the notion of professionalism extends beyond skill or knowledge to include values (Shaub & Braun, 2014).

Some studies have tried to understand auditors’ professional values and attitudes by analysing their professional commitment. According to Porter, Steers, Mowday, and Boulian (1974), professional commitment indicates a belief in the goals and values of the profession, a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the profession, and a desire to maintain membership of the profession. Suddaby et al. (2009) explored the degree of commitment to the core and ideal values of professional accountants in Canada. The authors concluded that the majority of accounting professionals are highly committed to their profession and that no inherent conflict between maintaining commitment to one's profession and to the employing organization was found. However, Gendron et al. (2006) offered another view: in a study carried out among chartered accountants in Canada, the authors concluded that the changes in the context of accounting work have eroded professional ethics.

Auditors’ professional values may vary over time, owing to the socialization processes that occur within the firms and the profession (Shafer, 2015). Academics (Gendron et al., 2006; Shafer, Lowe, & Fogarty, 2002; Suddaby et al., 2009) have shown a concern for how the current audit context, characterized by a non-professional environment that promotes the business of auditing, influences professional values and ethical standards.

In this regard, next section presents hypotheses with respect to the existence of differences in key professional values between students and auditors at different career stages. It also proposes hypotheses to test the relationship between key professional auditing values and ethical judgement.

HypothesesPublic interest commitmentThe concept of public interest is central to the accounting profession. However, very few studies have focused on developing an understanding thereof (Davenport & Dellaportas, 2009). Moreover, several authors argue that the degree to which auditors accept and acknowledge the core professional values has not been analyzed sufficiently (Suddaby et al., 2009). The ‘public interest’ has been defined as ‘the interests of third parties who rely on the opinions and advice delivered by the members of the accounting profession’ (Parker, 1987, p. 509).

In a study of Australian professional accountants, Davenport and Dellaportas (2009) examined their interpretation of the public interest. The authors found that the education process of accounting professionals appeared to be successful in transferring the meaning of the public interest. However, this training has not been as effective in guiding how the idea of the public interest should be applied in practice when conflicts of interest arise.

In this regard, it is important to acknowledge how those who are about to enter the profession understand the concept of the public interest. Accountants’ commitment to the profession is developed during a socialization process that occurs during formal education (Bline, Duchon, & Meixner, 1991; Clikeman et al., 2001; Cohen et al., 2001), and that continues throughout the career of the individual (Fogarty, 1992). Students in profession-related post-degree training are exposed to the values of the profession, such as serving the public interest and employing ethical behaviour (Scholarios, Lockyer, & Johnson, 2003). However, audit failures have been attributed to a lack of ethical behaviour, and the success of universities in enhancing the core values of the profession has therefore been questioned (Espinosa-Pike, 2001; Gonzalo Angulo, 2013; Helliar & Bebbington, 2004). Both students and auditors have had a formal accounting education. However, auditors’ attitudes towards the profession have also been formed by prior work experience and the organizational context in which they operate.

Several authors (Gendron et al., 2006; Shafer et al., 2002; Wyatt, 2004) argued that the shift in values related to the auditing context, namely from the public service ideal to a goal of profit maximization, may have had an influence on auditors’ attitudes towards the profession. Anderson-Gough, Grey, and Robson (2000) explored the process of socialization whereby auditors come to assume their professional identities, and the authors concluded that the client discourse is central to this process. According to these arguments, auditors will show a greater profit-oriented attitude than trainees will.

However, professional experience has been related to a higher professional commitment in the accounting field (Aranya, Pollock, & Amernic, 1981; Gendron et al., 2006; Goetz et al., 1991; Jeffrey, Weatherholt, & Lo, 1996). The basis for these results may be found in the literature of sociology of professions, which suggests that an individual's professional commitment develops during the process of socialization that starts when individuals enter such a profession (Larson, 1977; Jeffrey et al., 1996). The same arguments may apply to auditors’ commitment to core professional values, such as the service of public interest. In this regard, it could be expected that those auditors with extensive work experience will show a higher commitment to serving the public interest than students and less experienced auditors.

In order to advance the understanding of how the perception of public interest commitment evolves through the professional career, we present the following hypotheses:Hypothesis 1 Public interest commitment is statistically different between postgraduate students and auditors. There is a significant relationship between auditors’ rank and their public interest commitment.

Literature has studied the relationship between professional attitudes and the ethical decision-making process (Elias, 2006, 2008; Kaplan & Whitecotton, 2001; Lord & DeZoort, 2001). The results of studies on this relationship reveal that greater professional commitment leads to more ethical decision-making. According to Mintz (2015), accountants’ commitment to protect the public interest is the foundation for making ethical judgements in accounting. In this regard, we expect that auditors who prioritize serving the public interest will consider it unethical to engage in any practice that is unacceptable according to the ethical standards of the profession. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:Hypothesis 3 There is a negative relationship between auditors’ and students’ commitment to the public interest and their ethical judgement.

Independence is typically described as the central value of the auditing profession (Suddaby et al., 2009). However, there is ongoing debate as to how audit regulation can influence auditors’ behaviours, and which standards are most effective in managing the risk that auditors conduct their work in a non-independent way.

Because of a number of accounting scandals, measures have been taken to enhance auditors’ independence, both in fact and appearance, such as the US Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002 or The Revised Eight Company Law Directive of 2006 in the European Union. A system of more stringent prohibitions and penalties has arisen, in which regulators take on more active roles (Humphrey, Moizer, & Turley, 2006). These regulatory efforts assume that auditors can principally remain free of conflicts of interest by avoiding certain relationships (Taylor, DeZoort, Munn, & Thomas, 2003). However, some authors maintain that independence is a state of mind, and that it is therefore not possible to regulate situations that threaten independence (Gaa, 2006; Humphrey et al., 2006). A study conducted by Beattie, Fearnley, and Hines (2013) in the UK found that audit partners perceive many aspects of the post-SOX regulatory regime to be compliance driven (i.e. rules-based), and to have little impact on real audit quality.

Gendron et al. (2006, p. 172) stated that ‘While auditor independence was once viewed mainly as a moral-ethical position, it is today increasingly seen as an object that can be regulated through standards promulgated in codes of ethics and/or government regulations, and checked upon and verified through reviews and inspections’. However, according to these authors, regulatory enforcement contrasts with the ideals of professionalism, which assume that professional ethics are grounded in the character of the individual, and thus that the regulation of ethics is largely unnecessary.

This study analyses auditors’ and postgraduate students’ commitment to independence enforcement, also examining how this differs. Gendron et al. (2006) introduced the concept of independence commitment, which has been employed in subsequent studies in the auditing field (Carrington et al., 2013; Suddaby et al., 2009). Gendron et al. (2006, p. 170) defined independence commitment as ‘the extent to which the individual accountant considers auditor independence as a key attribute of the profession, and believes that regulatory standards of auditor independence (issued by the profession and/or external regulatory agencies) should be rigorously binding and enforced in the public accounting domain’. According to these authors, auditors who are committed to independence should take a positive view on the regulation of professional accountants’ ethics through the formulation of independence standards and rigorous enforcement regimes.

The change in the values that govern the auditors’ work context, i.e. from the logic of professionalism to the logic of commercialism, may have affected auditors’ commitment to the core professional value of independence. As Suddaby et al. (2009) exposed, high-ranking auditors’ professional norms are becoming more subordinated to managerial concerns, and are therefore less likely to support a rigorous enforcement of independence. These authors did not find statistically significant differences regarding the rigour and enforcement of independence requirements between auditors in high and low ranks in the firm. Nevertheless, Carrington et al. (2013) reported that the length of employment in auditing was positively associated with auditors’ commitment to independence enforcement and, similarly, Gendron et al. (2006) found that older public accountants showed a higher independence commitment than youngsters. Gendron et al. (2006) concluded that at the time when older auditors entered the profession, ethical values such as the principle of independence were more inculcated than they are today. The commitment to independence may have been ingrained in their mind ever since they entered the profession.

It is important to note that, in common with other code law countries, national audit law has enforced independence provisions in the Spanish regulations. Moreover, the scarce education on ethics that auditors have received in Spain focused on teaching the audit law without stressing the ethical reasoning or the core principles that underlie those legal standards (Espinosa-Pike, 2001). This legalistic approach might be reflected in auditors’ greater need of, and support for, rigid regulation.

In order to understand auditors’ and students’ commitment towards independence enforcement, and to explore how this commitment evolved along the audit career, we present the following hypotheses:Hypothesis 4 Commitment to independence enforcement is statistically different between postgraduate students and auditors. There is a significant relationship between auditors’ rank and their commitment to independence enforcement.

Several authors (Alleyne et al., 2013; Gendron et al., 2006; Suddaby et al., 2009) have called for further research into the influence of auditors’ commitment to independence enforcement on auditors’ ethical decisions.

The Independence Enforcement variable employed in this study (i.e. the degree to which auditors accept the importance of the enforcement of independence requirements) contrasts with a principle-based approach to standards, that establishes higher principles that rely on the professional judgement of the auditor. Based on the scarce prior literature we cannot predict that auditors that view positively the regulation of independence though a rigorous enforcement regime will show higher ethical judgement that those auditors supporting principles based standards. Therefore, due to the lack of prior research into the effects of auditors’ attitudes towards independence enforcement on auditors’ ethical decision-making, we do not predict the direction of such effects. Instead, we present the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 6 There is a relationship between auditors’ and students’ attitudes towards independence enforcement and their ethical judgement.

As literature states (Emerson, Conroy, & Stanley, 2007; Holtbrügge, Baron, & Friedmann, 2015), ethical judgement is defined in this study as the extent to which individuals consider unethical practices to be unacceptable according to the ethical standards of the profession.

Moral psychologist Rest (1986) developed the Four Component Model, which tries to explain the elements of ethical action. He concluded that ethical action is the product of these psychological sub processes: moral sensitivity (recognition), moral judgement or reasoning, moral motivation, and moral character. According to Rest's Four Component Model (1986), moral judgement is the second step in the ethical decision-making process and refers to the ethical judgements that individuals make about the courses of action previously identified. According to this ethical decision model, the ethical evaluation of the action influences the behaviour.

Auditors may be more aware of the ethical dilemmas of the audit profession than students do, due the fact that they have been exposed to ethical dilemmas in the course of their job. As Glover, Bumpus, Sharp, and Munchus (2002) suggested, experienced professionals have encountered similar situations and may be more aware of what is acceptable behaviour. Further, auditors may be more aware of the negative consequences that unethical behaviour involves for audit quality and for the reputation of the audit profession and audit firms. In this regard, Cohen et al. (2001) found that the accounting professionals viewed some questionable actions significantly less ethical than the graduate students did.

Moreover, one of the most important findings of research into moral psychology is that age is a forerunner of moral development (Rest, 1986). According to the Theory of Cognitive Moral Development by Kohlberg (1984), age is a variable that may significantly influence the development of levels of moral reasoning among individuals. Similarly, Rest (1986) indicates that ethical reasoning increases with age and education. In the audit context, age is highly related to auditors’ length of work experience; therefore, following Kohlberg's theory (1984), experienced auditors would be showing higher ethical judgement abilities.

Nevertheless, in the review of the literature regarding auditors’ ethical reasoning, Jones, Massey, and Thorne (2003) reported mixed results with respect to the effect of age. Ponemon (1992) concluded that experience had a negative impact on the ethical judgement of accountants. This author discussed how the selection-socialization process that occurs within audit firms leads to the promotion of auditors who possess lower and more homogeneous levels of ethical reasoning.

The literature presents conflicting arguments regarding the differences in the ethical judgement of auditors in different career stages. In order to advance in our analysis we present the following hypotheses:Hypothesis 7 Ethical judgement is statistically different between postgraduate students and auditors. There is a significant relationship between auditors’ rank and their ethical judgement.

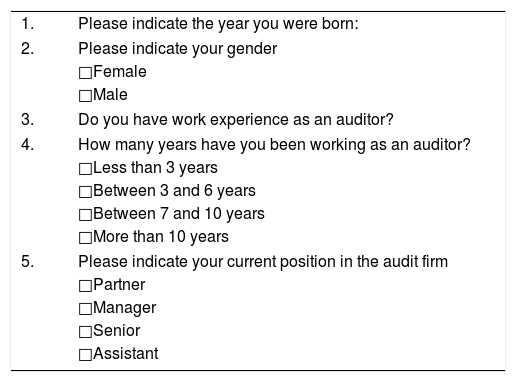

In order to address the research questions stated above, our research methodology comprised a survey that was distributed among auditors as well as among students enrolled in a postgraduate degree in auditing.

Before distributing the questionnaire (Appendix 1), a pilot test was carried out among auditors in a medium-sized audit firm. Additionally, the questionnaire was distributed to five academics that participated in a postgraduate auditing degree, and to two academics with experience as auditors. Minor changes were included in the questionnaire, as respondents to the pilot test did not exhibit comprehension difficulties.

Participation in the study was voluntary. Respondents were assured that the information would be used solely for the purpose of this study, and that this data collection process ensured their anonymity.

The survey was distributed in October 2012 among the members of one of the Spanish professional auditors’ bodies, comprised of auditors of small and medium-sized audit firms. The latter represent a considerable segment of the audit market in Spain: 98% of the Spanish audit firms are in this market segment, and represent over 30% of the total turnover (ICAC, 2016).

The professional organization informed its members about this study by means of a cover letter prepared by the authors explaining the purpose of the study, as well as a link through which the auditors could access the questionnaire. The responses were collected through online survey software.

The questionnaire was sent to the auditors twice. In total, 122 responses were obtained from auditors. In the first round, 80 individuals responded, while 42 responded in the second. To test for non-response bias, we compared the data of the first-round respondents with the data of the second-round respondents. The later respondents were considered as surrogates of non-respondents. No statistically significant differences were found between the responses of earlier and later respondents. Therefore, we concluded that no problems with respect to non-response bias existed.

The same survey questionnaire was distributed among students enrolled in a postgraduate degree in auditing from two Spanish universities. This degree is specifically directed at those interested in starting the auditing career. It provides the theoretical training of auditors, and validates the theoretical part of the examination that allows entry into the profession. Therefore, these students are potential recruits for audit firms. In total 55 responses were obtained from postgraduate students.

The questionnaire was distributed on site at the two universities one month after the ethical session had taken place. No statistically significant differences were found between the two universities.

Questionnaire and measurement of variablesThe first part of the questionnaire collected demographic data of respondents. Following this, the questionnaire included a series of close-ended questions concerning serving the public interest, ethical judgement, and independence enforcement.

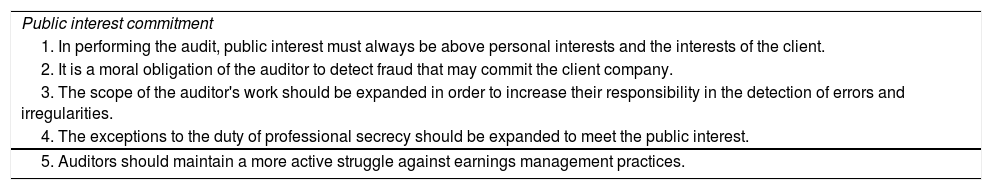

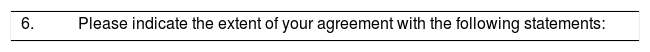

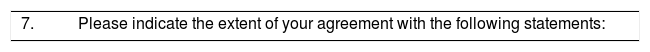

Public Interest Commitment. This measure was designed to assess the degree to which respondents believed that serving the public interest is auditors’ primary role, as well as their level of agreement with the duties that society expects from auditors, as is suggested by literature. Bobek, Hageman, and Radtke (2015) have measured public interest orientation with a single item, but as that construct might be ambiguous, we have taken their suggestion to develop it further and considered other items in addition to the public interest ideal (see Table 1). Our four additional statements were based on prior studies (Davenport & Dellaportas, 2009; Jenkins and Lowe, 2009). Participants had to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the five statements on a Likert scale, ranging from 1=completely disagree to 5=completely agree.

Measurement of independent variables.

| Public interest commitment |

| 1. In performing the audit, public interest must always be above personal interests and the interests of the client. |

| 2. It is a moral obligation of the auditor to detect fraud that may commit the client company. |

| 3. The scope of the auditor's work should be expanded in order to increase their responsibility in the detection of errors and irregularities. |

| 4. The exceptions to the duty of professional secrecy should be expanded to meet the public interest. |

| 5. Auditors should maintain a more active struggle against earnings management practices. |

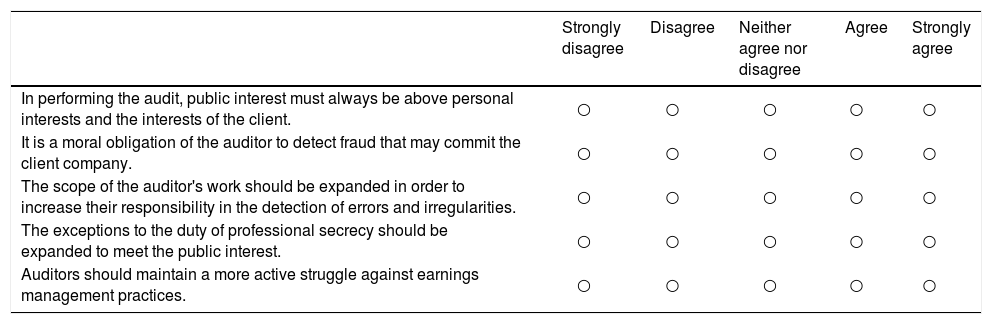

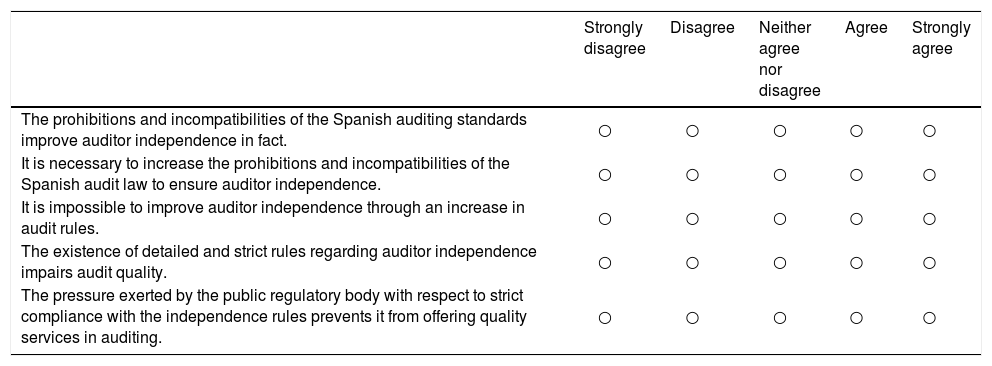

| Independence enforcement |

| 1. The prohibitions and incompatibilities of the Spanish auditing standards improve auditor independence in fact. |

| 2. It is necessary to increase the prohibitions and incompatibilities of the Spanish audit law to ensure auditor independence. |

| 3. It is impossible to improve auditor independence through an increase in audit rules.a |

| 4. The existence of detailed and strict rules regarding auditor independence impairs audit quality.a |

| 5. The pressure exerted by the public regulatory body with respect to strict compliance with the independence rules prevents it from offering quality services in auditing.a |

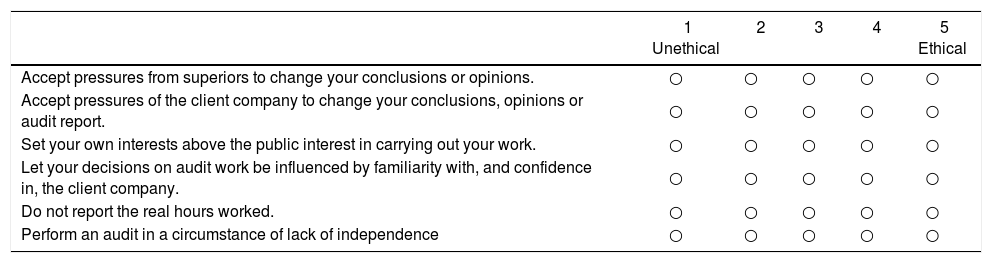

| Ethical judgement |

| 1. Accept pressures from superiors to change your conclusions or opinions. |

| 2. Accept pressures of the client company to change your conclusions, opinions or audit report. |

| 3. Set your own interests above the public interest in carrying out your work. |

| 4. Let your decisions on audit work be influenced by familiarity with, and confidence in, the client company. |

| 5. Do not report the real hours worked. |

| 6. Perform an audit in a circumstance of lack of independence. |

Independence Enforcement is designed to measure participants’ beliefs that regulatory standards of auditor independence should be rigorously enforced. The items that measure this variable were based on a study by Gendron et al. (2006), and were adapted for the Spanish regulatory environment (Table 1). Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with three statements related to independence requirements on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1=completely disagree to 5=completely agree.

Ethical Judgement. This variable refers to the acceptability, from an ethical point of view, of some of the questionable practices listed in Table 1. Respondents had to indicate the extent to which they would regard the six practices as ethical on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 is unethical and 5 is ethical. The extent to which respondents rated actions as ethical or unethical was used to measure ethical judgement in prior studies (Cohen, Pant, & Sharp, 1998; Conroy, Emerson, & Pons, 2010; Emerson et al., 2007; Espinosa-Pike & Barrainkua, 2016; Shafer & Simmons, 2011; Sweeney, Arnold, & Pierce, 2010).

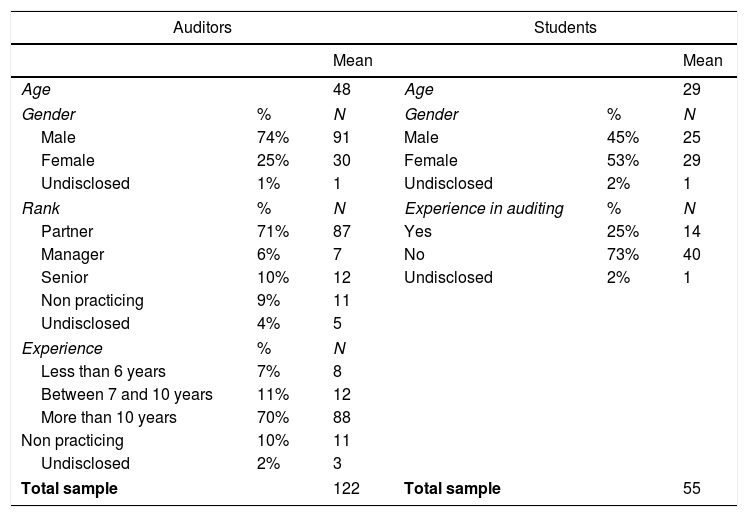

Demographic characteristics177 responses were included in this study, comprising 122 auditors and 55 students. Demographic details of the respondents are shown in Table 2.

Demographic data.

| Auditors | Students | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | ||||

| Age | 48 | Age | 29 | ||

| Gender | % | N | Gender | % | N |

| Male | 74% | 91 | Male | 45% | 25 |

| Female | 25% | 30 | Female | 53% | 29 |

| Undisclosed | 1% | 1 | Undisclosed | 2% | 1 |

| Rank | % | N | Experience in auditing | % | N |

| Partner | 71% | 87 | Yes | 25% | 14 |

| Manager | 6% | 7 | No | 73% | 40 |

| Senior | 10% | 12 | Undisclosed | 2% | 1 |

| Non practicing | 9% | 11 | |||

| Undisclosed | 4% | 5 | |||

| Experience | % | N | |||

| Less than 6 years | 7% | 8 | |||

| Between 7 and 10 years | 11% | 12 | |||

| More than 10 years | 70% | 88 | |||

| Non practicing | 10% | 11 | |||

| Undisclosed | 2% | 3 | |||

| Total sample | 122 | Total sample | 55 | ||

The average age of auditor respondents was 48. The majority of the auditors that participated in this study were male (74%), with female respondents representing a quarter of the total sample. The majority of the individuals in the sample (71%) were partners, and their experience in auditing was therefore in most of the cases over 7 years (81%). The long average duration of experience and the high rank of the participants explained the greater proportion of men in the sample. Career advancement in audit firms compromises personal lives, and this is generally a bigger deterrent to professional development in the case of women (Anderson-Gough et al., 2000; Fogarty, Parker, & Robinson, 1998; Krugman, 2000). This sample was therefore representative of the traditional pattern of the profession, and specifically of the Spanish auditing context (Carrera, Gutiérrez, & Carmona, 2001; Sierra Molina & Santa María Pérez, 2002).

The mean average age of student respondents was 29 years. It is noteworthy that females represented over half of the students (53%). This reflected that there is an increase in the proportion of women starting audit careers (Cohen et al., 1998). Finally, only 14 out of 55 students had experience in auditing. The length of experience of these students was less than two years for all the cases.

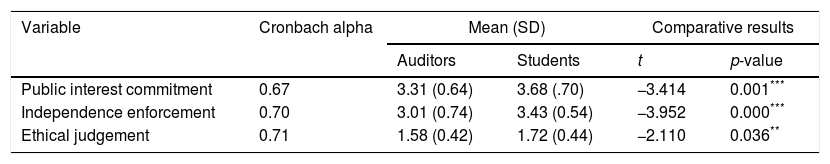

ResultsDescriptive results and ANOVA and t-test resultsFirstly, descriptive results of the constructs for each variable were presented for both auditors and students. These variables were measured by combining the responses to the statements shown in Table 1. Cronbach's alpha for the variables employed is over 0.70 (Table 3), except for public interest, which is near this value. The scales therefore showed sufficient internal reliability. The differences between auditors’ and students’ responses, as well as the differences among auditors’ responses at different career stages, were tested using t-tests and ANOVA tests. The assumption of normality of the dependent variable as well as the assumption of homogeneity of variance was met.

Descriptive statistics and comparative results for dependent variables.

Table 3 shows Cronbach's alpha for each construct, the descriptive statistics, and the t-tests results.

With regard to the variable Public Interest Commitment, the mean scores displayed in Table 3 suggest that Spanish auditors and students understood the role of auditors as serving the public interest, as well as the necessity of preserving this above all other interests. Moreover, Table 3 shows that both auditors and students generally agreed with the notion that the prohibitions improved independence in fact. Therefore, these results suggest that the respondents supported the role of legal regulation and public oversight to sustain the quality of audit services. It seems that both auditors and postgraduate students have internalized the regulatory efforts to improve auditors’ behaviours by focusing on the rigorous enforcement of independence rules. Further, the low score of the variable Ethical Judgement shows that both auditors and students considered the exposed situations to be unethical.

The differences between auditors and students were tested using t-tests. Results revealed that significant differences existed between auditors and students for the three variables under study (p<0.05). Therefore, Hypotheses 1, 4 and 7 were supported. First, the agreement reported by students regarding the role of auditors in serving the public interest is significantly higher than the agreement reported by auditors. Second, students showed a higher commitment to independence enforcement than auditors did. In this regard, they perceived the need to establish rules to safeguard independence to a greater extent than auditors did. This difference is statistically significant. Finally, auditors showed higher ethical judgement than students did, since they generally considered the questionable practices as less ethical.

In order to advance beyond an understanding of the differences between those in the profession and the future professionals, we also defined a goal of exploring how the perceptions varied throughout the professional career.

In an audit career, the length of experience and the position in the firm are closely related, as promotion depends largely on seniority. As indicated by the demographic variables, auditors involved in this study had extensive experience, and the majority of them therefore held high positions within the audit firm. To analyze if the professional values varied from the very beginning of their career until they become experienced auditors, we segregated the sample of the auditors into two categories: partners and non-partners. Accordingly, we conducted an analysis of variance test comparing students, non-partners, and partners. Due to the fact that 14 students had auditing practice (Table 2), we conducted two ANOVA tests. First, we considered students working in audit firms in the same category as auditors not holding partner positions (non-partners). Then, in a second test, these students were considered together with the rest of students in the postgraduate degree.

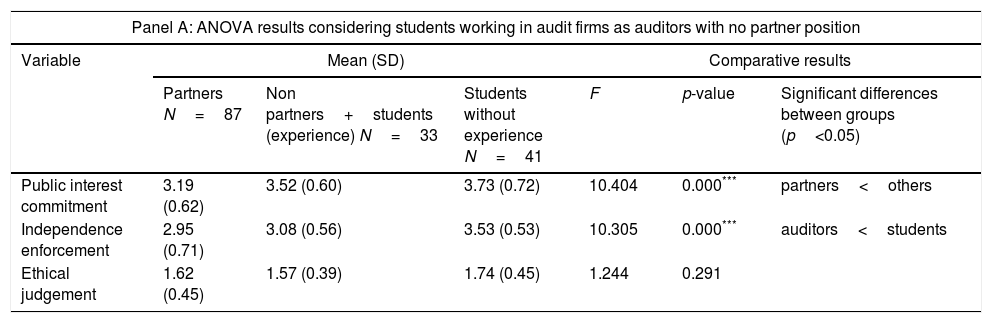

Results of the ANOVA test for the five dimensions are shown in Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and comparative results by auditors’ rank.

| Panel A: ANOVA results considering students working in audit firms as auditors with no partner position | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Comparative results | ||||

| Partners N=87 | Non partners+students (experience) N=33 | Students without experience N=41 | F | p-value | Significant differences between groups (p<0.05) | |

| Public interest commitment | 3.19 (0.62) | 3.52 (0.60) | 3.73 (0.72) | 10.404 | 0.000*** | partners<others |

| Independence enforcement | 2.95 (0.71) | 3.08 (0.56) | 3.53 (0.53) | 10.305 | 0.000*** | auditors<students |

| Ethical judgement | 1.62 (0.45) | 1.57 (0.39) | 1.74 (0.45) | 1.244 | 0.291 | |

| Panel B: ANOVA results considering all postgraduate students in the same category | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Comparative results | ||||

| Partners N=87 | Non partners N=19 | Students N=55 | F | p-value | Significant differences between groups (p<0.05) | |

| Public interest commitment | 3.19 (0.62) | 3.51 (0.59) | 3.68 (0.70) | 9.875 | 0.000*** | partners<students |

| Independence enforcement | 2.95 (0.71) | 3.03 (0.61) | 3.43 (0.54) | 8.125 | 0.000*** | auditors<students |

| Ethical judgement | 1.62 (0.45) | 1.48 (0.35) | 1.72 (0.44) | 2.581 | 0.079* | |

First, ANOVA results show that the responses to the perception on serving the public interest and independence enforcement were statistically different when considering experience in auditing or rank in the firm. Therefore, Hypotheses 2 and 5 were supported. Tukey's pairwise comparison was used to determine which firm categories were statistically different from each other. The results of the test (Table 4) indicate that auditors in partner positions showed less commitment to serving the public interest than the less experienced auditors and students. Further, students with no auditing experience revealed a greater commitment to independence regulation than the other categories. Overall, the same results were obtained when all postgraduate students were considered in the same category (Table 4, Panel B).

Additionally, t-tests were conducted to compare auditors in partner versus non-partner positions. Results revealed statistically significant differences for the variable Public Interest Commitment, showing that partners were less committed to serving the public interest than non-partners. These results are in line with ANOVA results in Table 4.

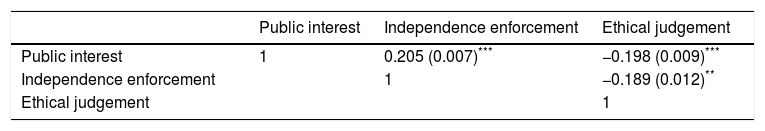

Correlation analysisThe exploratory study aimed to investigate the relationship between the variables under study. Accordingly, a correlation analysis was conducted. The results are presented in Table 5.

The correlation matrix shows a significant positive relationship between Public Interest Commitment and Independence Enforcement, indicating that auditors and students who showed a strong public interest commitment also exposed a high commitment to independence enforcement. Further, the significant negative relationship between Public Interest Commitment and Ethical Judgement reveals that those auditors who saw their role as serving the public interest considered the questionable practices as being less ethically acceptable.

The variable Ethical Judgement is negatively related to individuals’ commitment to independence enforcement, which indicates that those who believed that independence should be rigorously enforced, accepted to a lesser extent the questionable practices.

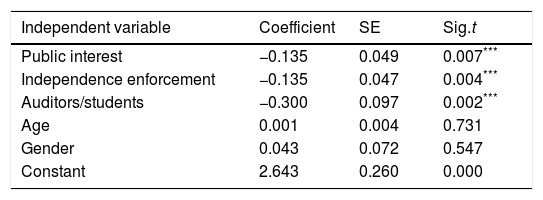

Multiple regression analysisIn order to test the effect of Public Interest Commitment and Independence Enforcement on auditors’ and students’ ethical judgement, a multiple regression analysis was carried out with Ethical Judgement as the dependent variable. This variable refers to the acceptability, from an ethical point of view, of the questionable practices listed in Table 1. In the regression model, we also test if auditors’ ethical judgement differs from those of students by including a dummy variable that takes 1 if the individual is an auditor and 0 otherwise.

The literature regarding auditors’ ethical decision-making has analyzed the influence of individuals’ gender and age on ethical decision-making (Ford & Richardson, 1994; Jones et al., 2003; O’Fallon & Butterfield, 2005). Moreover, the proportion of women in the sample of students was significantly higher than the proportion in the sample of auditors. The mean age of the respondents was higher for auditors than for students. These variables may have an influence in the results obtained so far. Therefore, in the regression model employed to test the hypothesis, we controlled for individual differences in terms of age and gender. The results are shown in Table 6.

Regression results for the model, with dependent variable ethical judgement.

| Independent variable | Coefficient | SE | Sig.t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public interest | −0.135 | 0.049 | 0.007*** |

| Independence enforcement | −0.135 | 0.047 | 0.004*** |

| Auditors/students | −0.300 | 0.097 | 0.002*** |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.731 |

| Gender | 0.043 | 0.072 | 0.547 |

| Constant | 2.643 | 0.260 | 0.000 |

Adj. R2=0.104; F=4.918; p=0.000.

The compliance with key assumptions (linearity between the dependent and independent variables, constant variance of the errors, and normality of the error distribution) was confirmed by using appropriate tests. The assumption of independence of errors is not significant for the purpose of this study, as there is no time series analysis involved.

The multiple regression is significant at the 0.01 level and has an explanatory power of 0.104. The results of the regression support H3, confirming the relationship between individuals public interest commitment and ethical judgement. The negative coefficient of the independent variable means that individuals who show higher commitment to the public interest consider the exposed situations to be less ethical. This means that the higher the public interest commitment, less acceptable they consider the questionable practices, and in this sense, higher is their ethical judgement.Hypothesis 6 Proposes the relationship between independence enforcement and ethical judgement is also supported. The negative coefficient of the independent variable means that individuals who show greater support for rigid independence standards and enforcement considered the exposed situations to be less ethical, so they present a higher ethical judgement.

It is important to note that the multiple regression results support the findings obtained in the independence tests presented previously in which auditors showed higher ethical judgement than students ethical judgement. Age and gender have no significant relationship with ethical judgement, as the regression results were the same when these control variables were excluded from the model.

Conclusions and implicationsThis paper advances in the study of auditors and students core professional values related to auditing such as commitment to public interest and independence enforcement. It analyses whether postgraduate students’ professional values differed from those of the auditors, and among auditors’ at different career stages. It also advances in the relationship between these two core auditing professional values and individual ethical judgement and in the existence of differences among the ethical judgement of postgraduate students and auditors.

Results reveal that the students’ commitment to serving the public interest was significantly higher than that of the auditors. Additionally, this public interest commitment decreased as auditors gained experience. The students’ higher commitment to public interest may signal the concern showed by academics regarding the commercialization of the profession. The current auditing context, in which the ‘business of auditing’ is emphasized, may damage the notion of the public service ideal.

With respect to the second core professional value under study: independence enforcement, the results reveal that students showed higher commitment to independence enforcement than auditors did. Further, the commitment to independence enforcement decreased as auditors gained experience. This result suggests that students perceived the need to establish rules to safeguard independence to a greater extent than auditors did. Further, auditors, as they gain experience, may have greater confidence in their own judgement and feel less comfortable with detailed independence rules that limit their professional judgement. In contrast, students may feel more confident following strictly the detailed rules.

Findings of this study reveal that postgraduate students show a high commitment to professional values such as public interest and independence enforcement. These results suggest that students in the postgraduate auditing course have adopted the beliefs and attitudes of the profession. These results are in agreement with previous research (Bamber & Iyer, 2002; Elias, 2006) that suggests that accountants develop a professional identification and adopt the profession's values before starting the professional career.

These findings are encouraging, as they suggest that the audit profession attracts individuals with high professional responsibility. However, the negative influence of experience on auditors’ commitment to the public interest and independence enforcement suggests that it is not enough to include ethical training in higher education; ethical training with an emphasis on professional responsibility should also be the target of auditors’ continuous professional development.

Another interesting result is that auditors showed higher ethical judgement than postgraduate students did. Auditors considered the questionable practices as less ethical than students did. A possible explanation for this result could be that auditors may have experienced similar ethical dilemmas in the course of their job, and may therefore be more aware of which should be the acceptable behaviour. Further, auditors are probably more conscious of the negative consequences of behaving in an unethical manner derived from the litigation and reputational risk for both audit firms and auditors themselves.

Our results do not support a negative effect of individuals’ experience on their ethical judgement. On the contrary, the results of this paper support Rest's (1986) theory where ethical judgement increases with experience and age.

It is also noteworthy that the correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between the variables under study. Auditors and students who showed a strong public interest commitment also exposed a high commitment to independence enforcement. These findings may reflect cultural features. In Spain, like in other European continental countries, the regulatory structure is based on the civil code. In such countries, the ethical guidelines for auditing have traditionally been established by legal regulations, and auditors may therefore equate meeting the public interest with strict compliance with legal standards. This would be in line with prior research into code-law jurisdictions (Gendron et al., 2006), and reflects the strong rule-orientation of Spanish auditors that was highlighted in previous studies (Espinosa-Pike, 2001).

Further, the regression analysis revealed the influence of auditors’ core professional values on ethical judgement. Auditors and students that showed a high public interest commitment and a high commitment to independence enforcement, also showed higher ethical judgement. Therefore, as suggested by prior literature (Elias, 2006; Jeffrey et al., 1996; Kaplan & Whitecotton, 2001; Lord & DeZoort, 2001), the extent to which individuals believed in the goals of the profession and were willing to exert effort in achieving them, was related to their ethical judgement. These findings reinforced the relevance of fostering the professional values in all stages of career development. Accordingly, our results support the proposals of academics and professional organizations (IAESB, 2014; Shaub & Braun, 2014) who suggest that ethical training programs with an emphasis on the values and responsibilities that distinguish the audit profession should be effective in fostering ethical decision-making.

The results of this study have important implications for professional organizations, audit firms, regulators, and universities. The values, ethics, and attitudes that the auditors bring to their work are key elements for audit quality (IAASB, 2014). Consequently, all of these agents should take the challenge of raising the ethical reasoning abilities of auditors, as well as of strengthening their professional responsibility to the public interest.

Professional organizations have the challenge to implement effective auditors’ continuous professional development programs focused on fostering the public interest ideal. However, not only professional organizations have a responsibility in doing that, audit firms play a key role in strengthening auditors’ values. An ethical climate within the audit firm that fosters professional values is fundamental for keeping high professional values in all stages of the professional life.

Our results suggest that Universities are doing their job in insufflating core professional values in auditing postgraduate students. Therefore, these results support the way Universities are training future professional accountants.

One limitation of this study is that, although several measures were taken to mitigate the social desirability problem (i.e. ensuring anonymity and on-line survey addressed directly to the authors), auditors may have answered in a socially desirable way and the results may have been affected by this bias.

Further, this research has been conducted in Spain. Therefore a geographic limitation may exist. The professional attitudes and perceptions of Spanish auditors may differ from those of auditors working in other cultural contexts. As it has been remarked previously, Spain is a civil code country where independence enforcement may have a different meaning to other common law countries and may not be related in the same way to ethical judgement.

Another limitation of this study refers to its cross-sectional design. A comparison between auditors in different ranks within the firms and students was taken as a proxy of the evolution of the attitudes of the auditors. In this regard, the research on the evolution of the core professional values in auditing would benefit from longitudinal studies. Future studies could extend, via qualitative and quantitative research, the socialization process that occurs within the audit firms and the auditing profession. This line of research would also extend our knowledge of the evolution of the professional and organizational identification of auditors as they advance in their professional careers. Such longitudinal studies could start by exploring the beliefs of students who have an objective of entering an audit firm, and by tracking those individuals as they gain experience in auditing.

In addition, the data gathered through the questionnaire is another limitation of this study. The questionnaire was sent only to auditors members of one of the Spanish professional auditors’ bodies, comprised of auditors of small and medium-sized audit firms leaving aside auditors of the other professional bodies in Spain. Consequently, the perceptions of auditors in the Big Four audit firms are not gathered in this study. In this regard, opportunities for future research emerge from extending the sample and analyses to auditors in the Big Four audit firms.

In future studies it would also be of great interest to investigate the effect of variables related to the characteristics of audit firms (such as size, ethical climate or nationality) on auditors’ professional values, such as public interest commitment and independence enforcement. In addition, it would be interesting to advance in the study of the effect of auditors’ professional and organizational commitment on auditors’ public interest commitment and independence enforcement. Further, there is a need for more studies that analyze how these professional values influence behavioural outcomes, such as auditor's ethical decision-making, turnover intention or dysfunctional behaviours. At this respect, future research that analyze the impact of auditors’ attitudes towards the core values of the profession on their ethical decisions would allow a greater understanding of the behavioural patterns of these professionals.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

| 1. | Please indicate the year you were born: |

| 2. | Please indicate your gender |

| □Female | |

| □Male | |

| 3. | Do you have work experience as an auditor? |

| 4. | How many years have you been working as an auditor? |

| □Less than 3 years | |

| □Between 3 and 6 years | |

| □Between 7 and 10 years | |

| □More than 10 years | |

| 5. | Please indicate your current position in the audit firm |

| □Partner | |

| □Manager | |

| □Senior | |

| □Assistant | |

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In performing the audit, public interest must always be above personal interests and the interests of the client. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It is a moral obligation of the auditor to detect fraud that may commit the client company. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The scope of the auditor's work should be expanded in order to increase their responsibility in the detection of errors and irregularities. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The exceptions to the duty of professional secrecy should be expanded to meet the public interest. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Auditors should maintain a more active struggle against earnings management practices. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The prohibitions and incompatibilities of the Spanish auditing standards improve auditor independence in fact. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It is necessary to increase the prohibitions and incompatibilities of the Spanish audit law to ensure auditor independence. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It is impossible to improve auditor independence through an increase in audit rules. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The existence of detailed and strict rules regarding auditor independence impairs audit quality. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The pressure exerted by the public regulatory body with respect to strict compliance with the independence rules prevents it from offering quality services in auditing. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| 1 Unethical | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 Ethical | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accept pressures from superiors to change your conclusions or opinions. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Accept pressures of the client company to change your conclusions, opinions or audit report. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Set your own interests above the public interest in carrying out your work. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Let your decisions on audit work be influenced by familiarity with, and confidence in, the client company. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Do not report the real hours worked. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Perform an audit in a circumstance of lack of independence | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |