Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Autoimmune Diseases

Más datosThis article will mention the essential aspects of managing ILD associated with systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inflammatory myopathies (IIM). The prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) has recently improved because of tighter control of RA disease activity. This article presents recent evidence of the effect of methotrexate on RA-ILD, which is associated with a better prognosis. The available alternatives include the use of anti-fibrotic drugs. In managing interstitial lung disease related to anti-synthetase syndrome (ASSD-ILD) and anti-MDA5-associated ILD, immunosuppression and anti-fibrotic drug regimens are relevant aspects mentioned.

Este artículo señala los aspectos esenciales del manejo de la enfermedad pulmonar intersticial (EPI) asociada con algunas enfermedades autoinmunes sistémicas, como la EPI asociada con la artritis reumatoide (AR) y las miopatías inflamatorias (MI). El pronóstico de la enfermedad pulmonar intersticial asociada con la artritis reumatoide (EPI-AR) ha mejorado recientemente, debido a un control más estricto de la actividad de la AR. El artículo presenta evidencia reciente del efecto del metotrexato en la EPI-AR, que se asocia con un mejor pronóstico. Las alternativas disponibles incluyen el uso de fármacos antifibrosantes. En el manejo de la enfermedad pulmonar intersticial asociada con el síndrome anti sintetasa (EPI-SAS), así como en la EPI asociada con el anticuerpo anti MDA5, se menciona el uso de fármacos inmunosupresores y antifibrosantes.

In this article, we will mention the essential aspects in the management of ILD associated with some systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inflammatory myopathies (IM), always supported with the best available evidence, and mention aspects that, based on the experience gained, are relevant to us in the management of these conditions.

Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD)The first step in adequately treating a patient with RA-ILD is proper diagnosis. A multidisciplinary evaluation should be performed1 between the rheumatology team, pulmonology, and experts in the interpretation of imaging studies and pulmonary pathology, to classify the pattern of lung damage according to ATS/ERS recommendations.2 It is essential to define whether the patient has an interstitial pulmonary process or any differential diagnoses that may confuse the diagnosis. The above is easy to write but challenging to execute in practice, as it requires medical personnel with experience evaluating ILD. Referral to a center specialized in caring for this group of patients should always be considered.

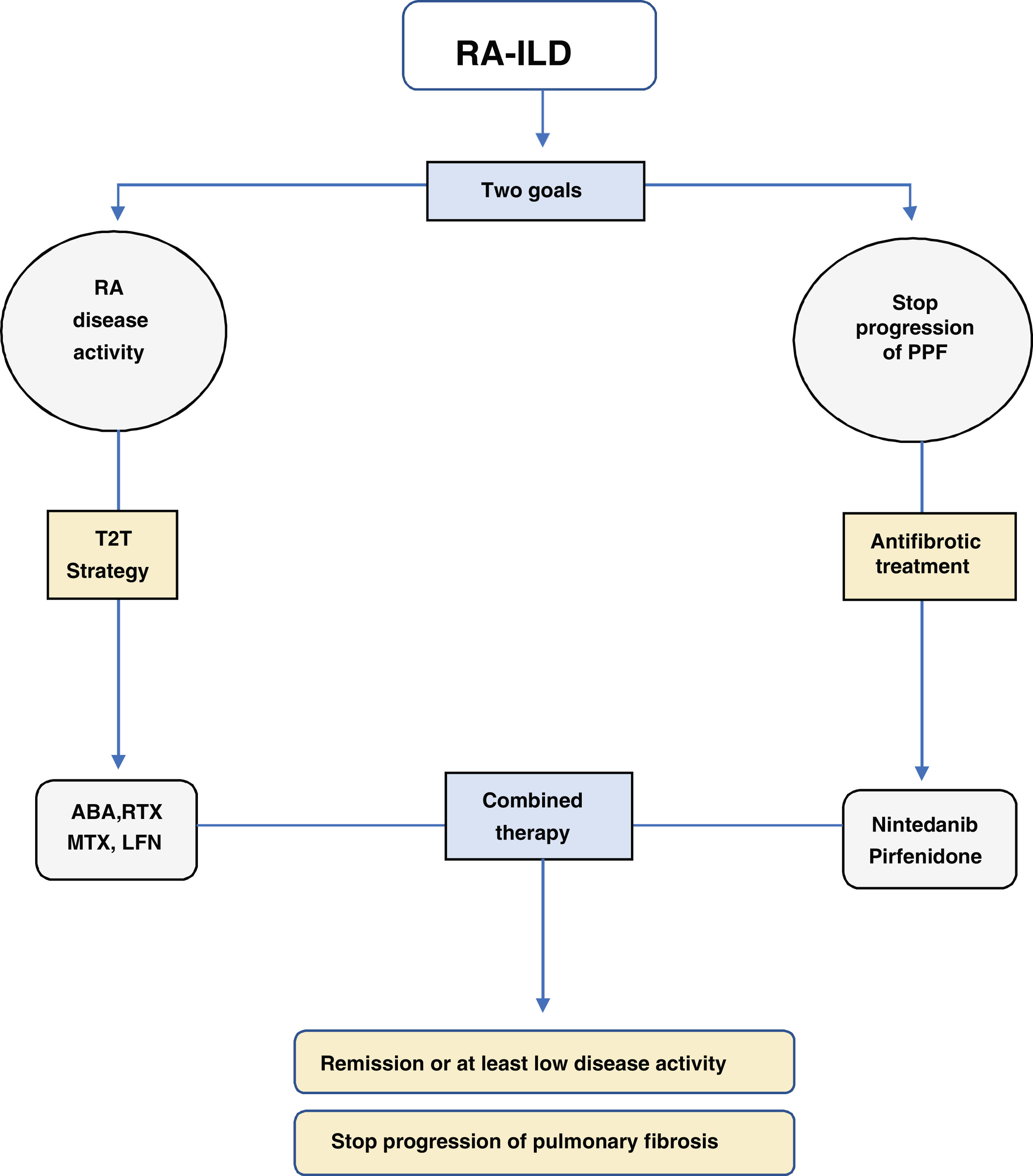

Once the diagnosis of ILD has been confirmed and classified according to the pattern of damage, two fundamental pillars should be considered in the management of RA-ILD (Fig. 1):

- 1.

Strict control of RA disease activity

- 2.

Treatment with anti-fibrotic drugs

One of the most important developments is that high RA activity has been associated with mortality in RA-ILD.3,4 Practically all the recently published RA-ILD cohorts have reported an increase in survival, going from a median survival of 3.2 years5–7 to a median survival of about eight years.8–10 In other words, tight control of RA activity has increased survival; therefore, the first step in treating a patient with RA-ILD is to carry out a strategy with the target of remission of RA disease activity, the so-called treat-to-target (T2T) strategy.11

What drugs are used to treat RA activity?Due to the risk of so-called methotrexate (MTX) pneumonitis, it has been proposed to use another conventional disease-modifying drug, when possible, in treating patients with RA-ILD.1 This strategy ignores recent evidence. All the papers published in recent years describe a protective effect for the survival of patients treated with methotrexate compared to those who did not receive this drug.9,12,13 The effect of MTX is not limited to a better prognosis in survival but is also strongly associated with the protection of lung function, being a factor associated with a lower risk of lung disease progression (OR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.09–0.76).12 Recently, Chang et al. confirmed that not receiving methotrexate is strongly associated with the risk of rapid lung disease progression or death (RR: 8.07, 95% CI: 1.82–35.77).13 Some would argue that MTX may give a risk of MTX pneumonitis, an idiosyncratic reaction to the drug. Sparks et al.14 reported a risk of 0.003 for possible methotrexate pneumonitis in subjects without RA and a high risk for cardiovascular disease treated with methotrexate. Two authors of this article (MM & JRS) have collaborated for 17 years at a national referral center of pulmonary disease, where we evaluated multiple cases of possible pneumonitis due to MTX without being able to diagnose a single definitive case of pneumonitis due to this drug. On the other hand, in a socioeconomic environment with limited access to biological or synthetic disease modifiers, MTX is a feasible option to treat RA activity in patients with RA-ILD. Therefore, recommending not to use a drug associated with a better prognosis in survival for fear of a less than 1% risk for MTX pneumonitis is entirely wrong. In our institution, MTX is always part of the initial management of all patients with RA-ILD.

There are other therapeutic options besides MTXBefore considering which biologic or synthetic DMARD to use, including MTX, it should be clear that the real goal is to achieve remission of RA following a T2T strategy. It is essential to mention that in case the clinician responsible for treating the patient with RA-ILD does not feel comfortable initiating MTX, other options are available. Among the therapeutic options, we have leflunomide (LFN)15 and biological agents such as rituximab (RTX) and abatacept (ABA). In the case of LFN, our usual practice is to initiate combined treatment with MTX and LFN, together with a variable dose of prednisone, between 10mg/day and never more than 50mg/day with a stepwise reduction of the PDN dose. Regarding the use of biological agents, there is experience with ABA16–18 either as monotherapy, in combination with MTX, or combination with other synthetic DMARDs. These studies are retrospective in nature and merely descriptive. Based on these studies, it has been proposed that ABA is an effective and safe option for treating RA-ILD. RTX is also recommended as a therapeutic option in RA-ILD.19–21 In our experience, both biologics are suitable options for managing patients with RA-ILD; there are small case series in which treatment with tocilizumab (TCB) is described with apparent control of both RA disease activity and lung function.22 Jak inhibitors have also been used to manage RA-ILD.23,24 Experience is limited, but interestingly, tofacitinib has been consistently associated with a lower incidence of RA-ILD.25,26 Therefore, evaluating the safety and efficacy of this drug in RA-ILD in clinical trials seems relevant.

According to some experts, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) has a role in managing RA-ILD.27,28 There is even information that MMF may be associated with lower mortality.10 In our center, we do not use it; in direct conversations with some who propose that MMF may be effective, we know they use it with synthetic DMARDs or biologics.

Which drugs are not to use in the management of RA-ILD?Azathioprine and cyclophosphamide are contraindicated in the management of RA-ILD. In the current era, neither drug has a role in managing the inflammatory joint disease of RA, and are associated with increased mortality from pulmonary causes in this group of patients.10 There is reasonable doubt whether anti-TNF-alpha drugs are associated with a worse prognosis in RA-ILD.10 Our position is to adopt a pragmatic approach. If a decision is about to escalate treatment in a patient with RA-ILD according to a T2T strategy, we prefer ABA or RTX rather than an anti-TNF-alpha. Suppose the patient is already on treatment with an anti-TNF alpha, has no evidence of pulmonary deterioration, and has achieved adequate control of RA activity: in that case, we do not make any therapeutic modification.

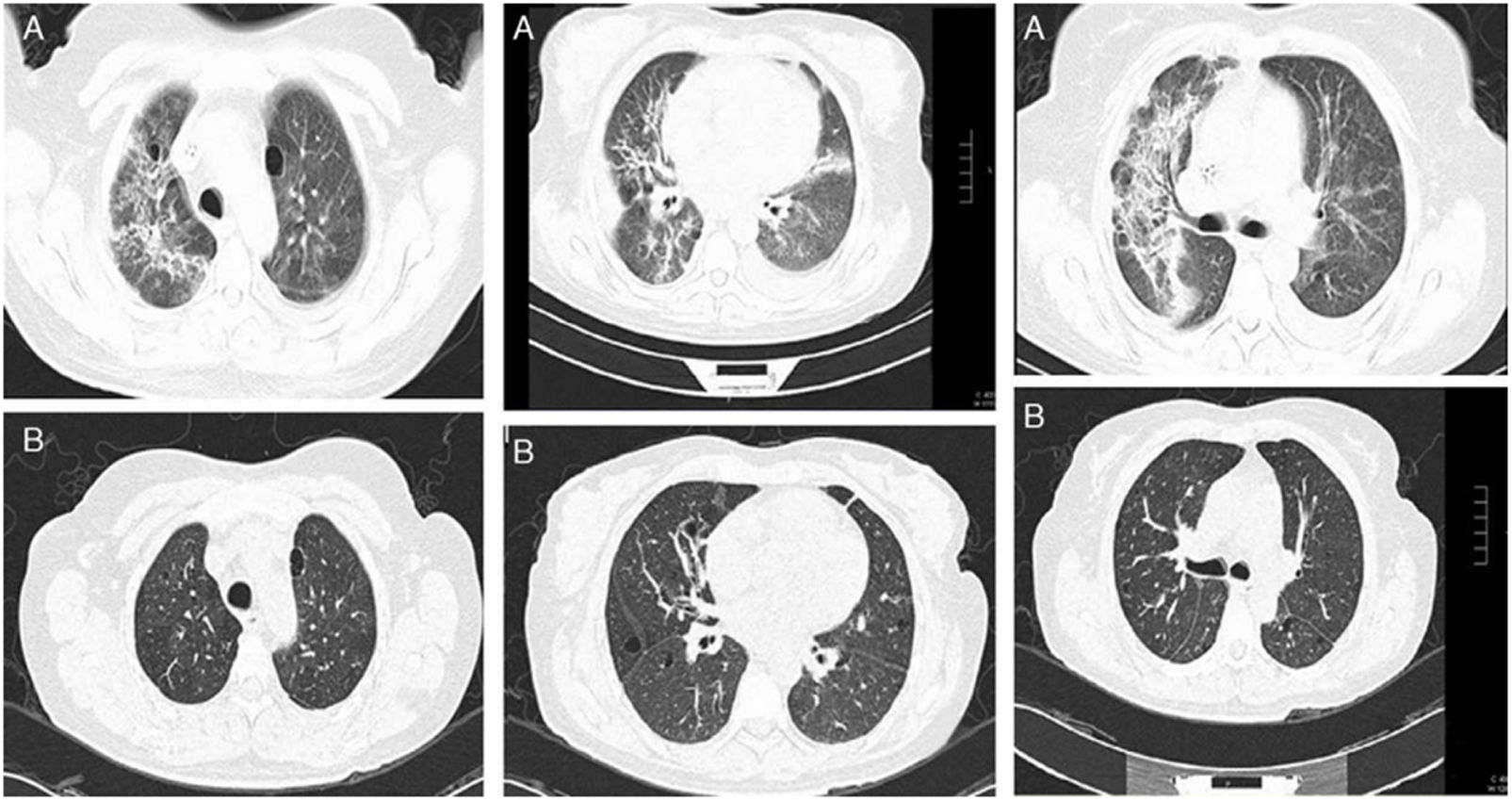

Use of glucocorticoids in RA-ILDThe inflammation at the pulmonary level correlates with the ground-glass image on high-resolution chest tomography (HRCT) and may improve with glucocorticoids.29 Our working group described that patient with RA-ILD treated with glucocorticoids at a maximum daily dose of 50mg prednisone/day, together with DMARDs,29 can improve in observed forced vital capacity (FVC) at six months after initiation of treatment, with up to 15% absolute difference. This improvement correlates with decreased ground glass and consolidations observed on HRCT29 (Fig. 2). However, this improvement is not observed in fibrosing patterns; on the contrary, patients with RA-ILD with usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) or fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) patterns may have a behavior of ILD, such as progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF).2,30

(A) Baseline HRCT of a patient with RA-ILD, showing perivascular and randomly distributed cysts, with ground-glass opacities and areas of pulmonary consolidation with bronchocentric thickening of the interstitium. (B) HRCT one year after starting treatment with prednisone and methotrexate. A significant decrease in ground glass, resolution of the consolidation areas and bronchocentric thickening of the pulmonary interstitium.

Image from Rojas-Serrano J, González-Velásquez E, Mejía M, Sánchez-Rodríguez A, Carrillo G. Interstitial lung disease related to rheumatoid arthritis: evolution after treatment. Reumatologia Clinica. 2012;8:68–71.

In practice, it is advisable to discuss with the imaging expert the degree of extension of the findings on HRCT compatible with inflammation and decide on treatment with glucocorticoid based on that. If the extension is greater than 20% according to the Goh scale, there is no doubt that prednisone with a maximum dose of 50mg/day may benefit the patient. In case of a lesser extent, a dose between 20 to 50mg of prednisone per day should be decided on a case-by-case basis. Generally, the initial dose is maintained for 4–6 weeks, and then a gradual decrease of the glucocorticoid dose is initiated. In office visits and daily consultations, a frequent comment that one of the authors (JRS) makes to the medical team is that he has never regretted prescribing or increasing the prednisone dose in a patient with RA-ILD. Still, he has occasionally questioned whether to decrease or discontinue the dose. Recently, a literature citation that justify that comment was published. Chang et al.13 reported that glucocorticoid use is strongly associated with protection against lung disease progression and/or death (RR: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.09–0.81). One explanation is that despite the adverse effects associated with glucocorticoid therapy, judicious use of glucocorticoids in a patient with RA-ILD contributes to tighter control of RA activity, reflected in the decreased inflammatory process in the lungs.

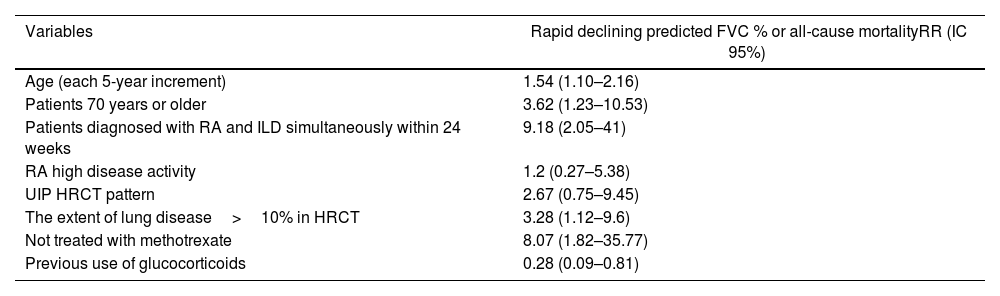

Treatment with anti-fibrotic drugsRA-ILD can behave like progressive PPF. Recently, Chang et al.13 reported that 64% of patients with RA-ILD have progression of ILD during a 3-year follow-up period. In addition, they described risk factors associated with rapid progression of ILD and/or mortality (Table 1). Briefly, these are older age, simultaneous diagnosis of RA and ILD, an extension of ≥10% of ILD on high-resolution chest CT (HRCT), and not having received methotrexate (RR: 8.07, 95% CI: 1.82–35.77). Finally, the use of glucocorticoids was associated with protection against the progression of ILD (RR: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.09–0.81).

Risk factors for rapid PPF in RA-ILD patients.

| Variables | Rapid declining predicted FVC % or all-cause mortalityRR (IC 95%) |

|---|---|

| Age (each 5-year increment) | 1.54 (1.10–2.16) |

| Patients 70 years or older | 3.62 (1.23–10.53) |

| Patients diagnosed with RA and ILD simultaneously within 24 weeks | 9.18 (2.05–41) |

| RA high disease activity | 1.2 (0.27–5.38) |

| UIP HRCT pattern | 2.67 (0.75–9.45) |

| The extent of lung disease>10% in HRCT | 3.28 (1.12–9.6) |

| Not treated with methotrexate | 8.07 (1.82–35.77) |

| Previous use of glucocorticoids | 0.28 (0.09–0.81) |

The concept of PPF has revolutionized the treatment of fibrosing ILD other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). We now know that administering an antifibrotic drug (nintedanib) in a heterogeneous group of subjects with PPF, which included subjects with RA-ILD, can delay the progression of PPF regardless of the etiological process that caused the PPF.31–33 Importantly, nintedanib has a number needed to treat of 7 to prevent progression or death across the entire spectrum of PPF.32 Pirfenidone has been evaluated as an antifibrotic drug for treating RA-ILD.34 Although the clinical trial had to be stopped due to slow recruitment, the results suggest that pirfenidone may delay the progression of RA-ILD. Therefore, antifibrotic therapy should be considered in RA-ILD patients, especially in subjects with documented progression and with risk factors for rapid progression or death (Table 1).

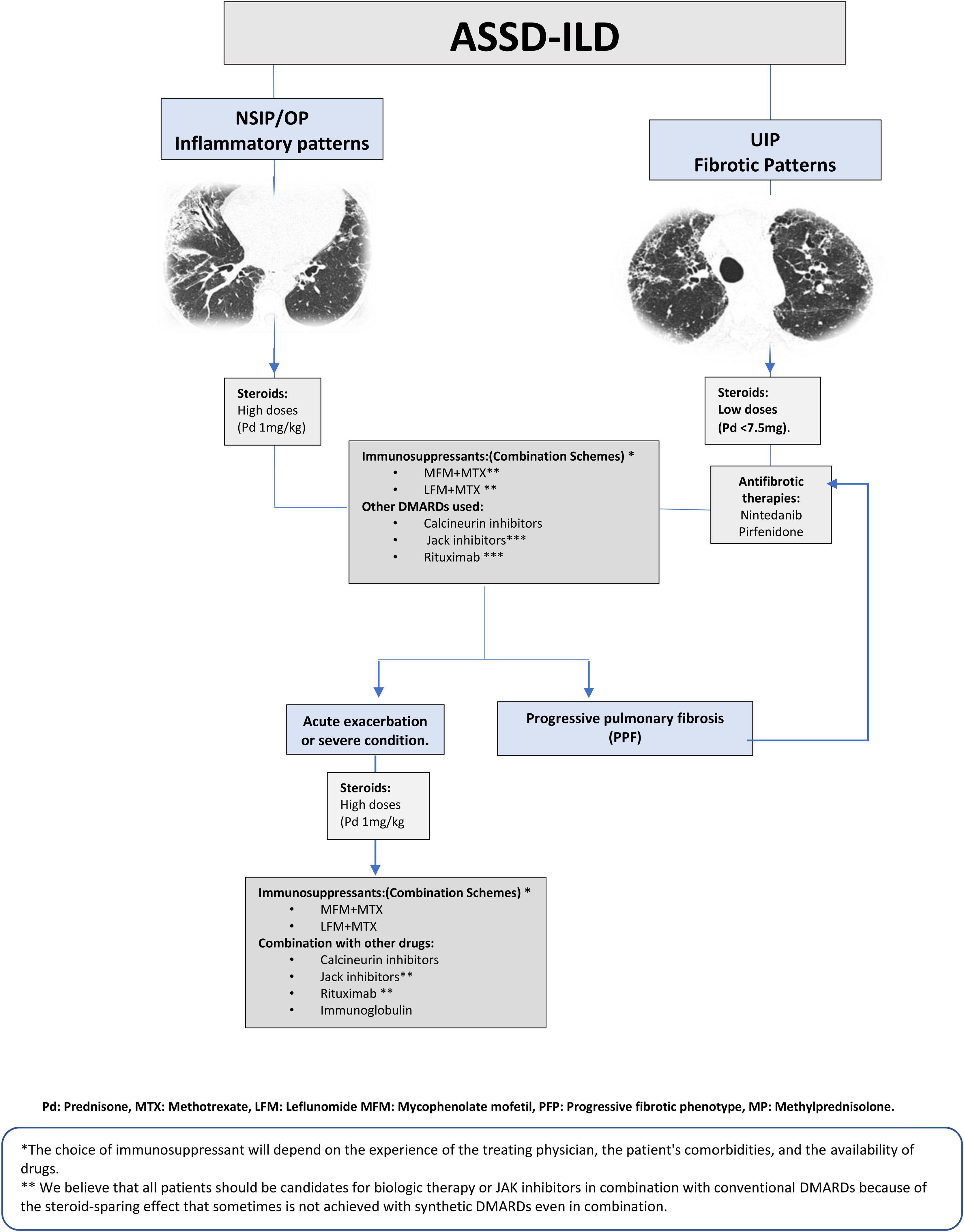

Treatment of IIM-ILDTreatment of interstitial lung disease related to anti-synthetase syndrome (ASSD-ILD)Any adequate treatment begins with a correct diagnosis. However, in anti-synthetase syndrome (ASSD), there is a very confusing element from a rheumatological point of view: many patients do not have muscular or articular manifestations. And to make matters worse, the antibody patterns associated with the worst prognosis, such as PL7 and PL12, are the ones with the lowest prevalence of these clinical signs.35,36 Therefore, our first practical recommendation is that every patient with a NSIP with or without organizing pneumonia (OP), positive to anti-synthetase autoantibodies (ASAB), should be treated as ASSD despite not meeting the criteria for an inflammatory myopathy, This recommendation is based on the fact that 85% of patients with an ASAB-associated ILD have a NSIP or NSIP/OP pattern, and 76% have improvement or stability pulmonary function with prednisone treatments along with immunosuppressants.37 However, about 15% of subjects with ASAB-positive ILD have an HRCT pattern compatible with UIP and may have a course of PPF.37

In the setting, multiple drugs have been reported to have a beneficial effect on lung disease progression, and these reports are congruent with our clinical experience.38,39 However, we do not want to neglect to mention that these drugs are generally used in combination. For example, MMF is reported to be effective, but when reading the document carefully, one notes that this drug was added to a background scheme.40,41 Taking the above into account, we initiate in patients with ASSD-ILD a combined strategy, which in most of them includes prednisone with doses no higher than 50mg/day and methotrexate 12.5mg per week, and leflunomide 100mg weekly cumulative dose.37 The prednisone dose is maintained for six weeks to initiate a tapering schedule; upon reaching an amount of 10mg per day, the tapering is much slower and monitored for signs of relapse. A valuable clinical data is to watch for the presence of the mechanic's hands or hiker's feet signs. These correlate with ASSD activity at the pulmonary level, and their presence may indicate a relapse of lung disease. Several questions must be answered in treating patients with ASSD-ILD: which scheme is the most effective and safe, and are all candidates for rituximab or Jak inhibitors as a first therapeutic option? These questions should be answered in clinical trials once we have a validated classification system for ASSD. However, 24% of patients with ASSD-ILD have disease progression.37 The risk factors associated with PPF are older age at diagnosis, UIP pattern, and greater severity of lung disease, as reflected in spirometry and DLCO results. Another factor associated with progression is the presence of traction bronchiectasis in the middle lobe, which reflects a fibrotic component.37,42 In our experience, patients with UIP patterns that progress have a rapidly progressive feature, so we suggest starting treatment with anti-fibrotic drugs as soon as possible. The general treatment scheme is presented in Fig. 3.

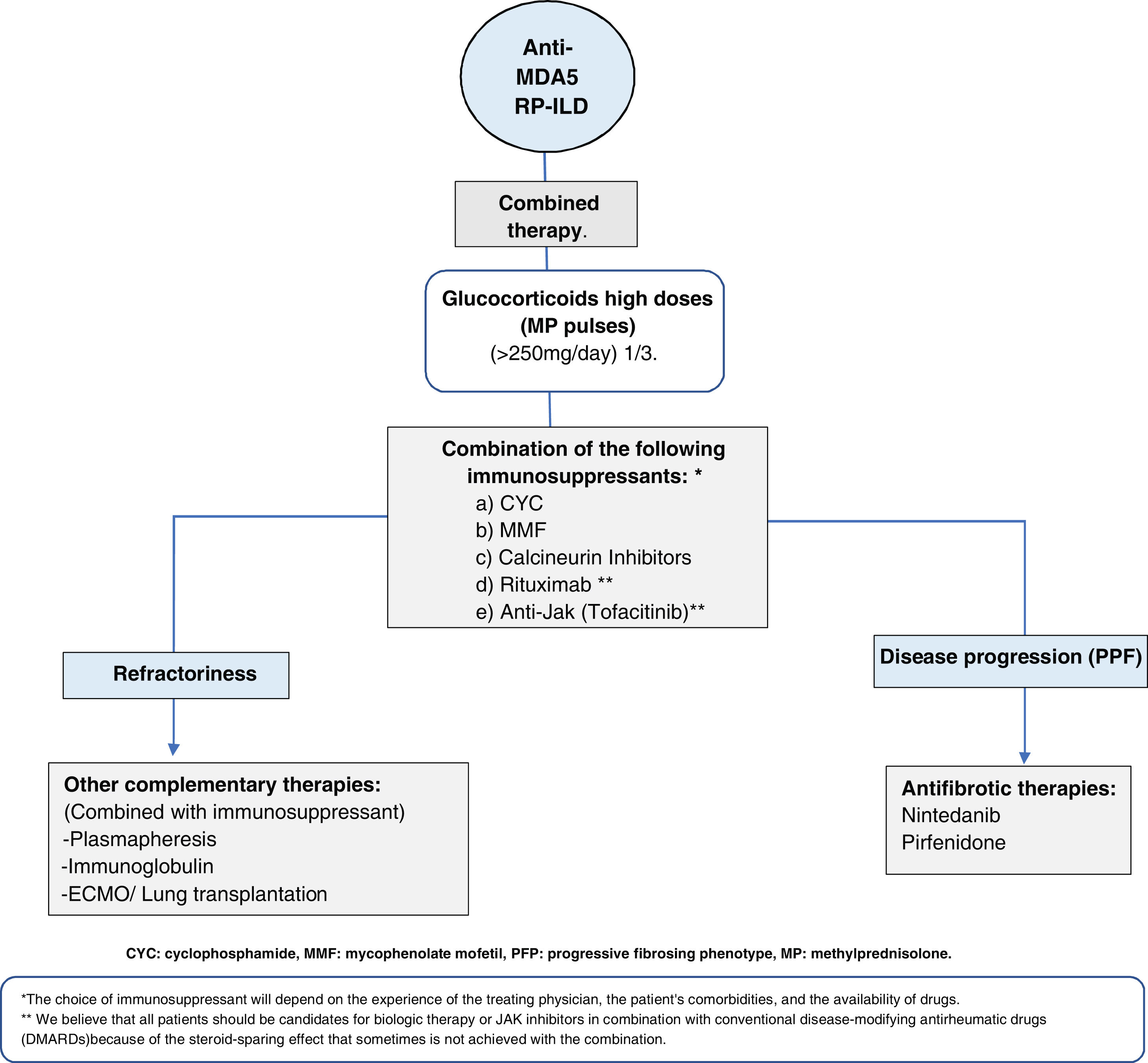

Anti-MDA5-positive dermatomyositis associated with interstitial lung disease (MDA5-ILD)This entity is considered a therapeutic challenge because of its poor response to treatment and high mortality, reported from 33 to 66% in the first six months after diagnosis.43,44 Therefore, timely diagnosis and early initiation of aggressive immunosuppressive therapy are essential. MDA5-ILD patients are at high risk of rapidly progressive lung disease (RP-ILD), which may present complications with increased mortality, such as pneumo-mediastinum. It has been estimated that 40 to 60% of patients with MDA5+-ILD have this behavior.44,45 The variables associated with a higher risk of RP-ILD are cutaneous manifestations, high titers of anti-MDA5 levels, and a more significant extension of pulmonary disease.46

What would be the best therapeutic plan for these patients? One of the best-described and evaluated schemes is triple immunosuppressive therapy combined with high-dose glucocorticoids as soon as possible47 (Fig. 4). It is important to emphasize that in the early stages of the disease, there is diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), evidenced in high-resolution tomography (HRCT) as ground glass opacities with a patchy distribution. At this stage, the initiation of effective therapy could modify the rapidly progressive course. If this first phase is not adequately treated, a second phase characterized by respiratory deterioration, the increased extent of lung damage on HRCT, and refractoriness to treatment may occur, being the only option ECMO as a bridge to lung transplantation.45,48,49 It has been reported that they may have a progressive fibrosing evolution in the first two months after diagnosis, with the appearance of reticulations and distortion of the architecture in HRCT, which leads to an irreversible loss of lung volume, requiring anti-fibrotic therapy adjuvant to immunosuppressive treatment from the first months of diagnosis.44 In addition to the triple immunosuppressive scheme, other schemes have been described using, for example, Jak inhibitors.50–52Fig. 4 describes some schemes used in this entity.

ConclusionsAlthough no clinical trials have rigorously evaluated therapeutic regimens in RA-ILD, ASSD-ILD, and MDA5+ILD, based on existing descriptive and cohort studies, a therapeutic approach that combines reduction of the inflammatory burden of the underlying disease with disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, including methotrexate especially in management of rheumatoid arthritis, with antifibrotic agents in patients who have a progressive fibrosing lung disease phenotype has led to lessening of the burden of the associated lung disease.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interest- •

Jorge Rojas Serrano declares having received fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squib for conferences and consultancies; he has received funds from Pfizer for research projects proposed by the researcher.

- •

Mayra Mejía reports having received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim for conferences and consultancies.

- •

Daphne Rivero-Gallegos has nothing to declare.