SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination have prompted extensive research into the potential of this virus to induce autoimmunity and, in certain cases, contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases. However, the presence of latent autoimmunity and their role in the transition to overt autoimmune conditions remain poorly understood.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the prevalence of latent autoimmunity among healthcare workers (HCWs) with natural, vaccine-induced, and hybrid immunity to SARS-CoV-2.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a prospective observational study with 50 HCWs to assess the presence of latent rheumatic, thyroid, and phospholipid autoimmunity. Participants comprised HCWs with no previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or those who had undergone natural infection and subsequently received a COVID-19 booster vaccination.

ResultsThe evaluation of 25 autoantibodies associated with latent rheumatic, thyroid, and phospholipid autoimmunity revealed no statistically significant differences among the studied groups.

ConclusionsNatural infection with SARS-CoV-2, vaccination, or hybrid immunity against this virus was not associated with the development of new-onset latent autoimmunity.

La infección por SARS-CoV-2 y la vacunación contra el COVID-19 han impulsado una extensa investigación sobre el potencial de este virus para inducir autoinmunidad y, en ciertos casos, contribuir al desarrollo de enfermedades autoinmunes. Sin embargo, la presencia de autoinmunidad latente y su papel en la transición hacia condiciones autoinmunes manifiestas siguen siendo poco comprendidos.

ObjetivoEvaluar la prevalencia de autoinmunidad latente en trabajadores de la salud (TDS) con inmunidad natural, inducida por vacunación e híbrida al SARS-CoV-2.

Materiales y métodosRealizamos un estudio observacional prospectivo con 50 TDS para evaluar la presencia de autoinmunidad latente reumática, tiroidea y de fosfolípidos. Los participantes fueron TDS sin exposición previa a SARS-CoV-2, o que habían experimentado una infección natural seguida de una vacunación de refuerzo contra COVID-19.

ResultadosLa evaluación de 25 autoanticuerpos asociados con autoinmunidad reumática, tiroidea y de fosfolípidos no reveló diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los grupos estudiados.

ConclusionesLa infección natural por SARS-CoV-2, la vacunación o la inmunidad híbrida contra este virus no se asociaron con el desarrollo de autoinmunidad latente.

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has had a profound impact on global health, leading to significant morbidity and mortality [1]. SARS-CoV-2 infection can result in a wide range of clinical outcomes, from asymptomatic or mild symptoms to severe complications and death. Although the initial focus was on the acute respiratory and systemic effects of COVID-19, growing evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 can also trigger autoimmune responses. Several immunological mechanisms, including molecular mimicry, epitope spreading, and bystander activation, have been implicated in the development of autoimmunity following SARS-CoV-2 infection, leading to the breakdown of self-tolerance and the development of autoimmune diseases (ADs) [2,3]. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 infection induces hyperinflammation through cytokines storm and immune cell dysfunction (including macrophages, neutrophils, T and B cells, among others), which can contribute to tissue damage and the initiation of autoimmune processes [3]. These responses may manifest as new-onset ADs or exacerbate pre-existing autoimmune conditions, raising questions about the long-term immunological consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 have been crucial in controlling the COVID-19 pandemic. Some studies report de novo ADs after vaccination [4,5], but others suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection increases AD risk, which vaccination may mitigate [6].

After SARS-CoV-2 infection, latent autoimmunity has been described, characterized by the presence of autoantibodies without clinical manifestations of ADs [7–9]. This preclinical phase of autoimmunity poses a risk for the future development of clinically significant ADs.

In this context, our study aims to evaluate latent autoimmunity in healthcare workers (HCWs) who have experienced COVID-19 (natural infection), received mRNA booster vaccines (induced immunity), or both (hybrid immunity). Understanding latent autoimmunity in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination is crucial for optimizing public health strategies and ensuring long-term health outcomes.

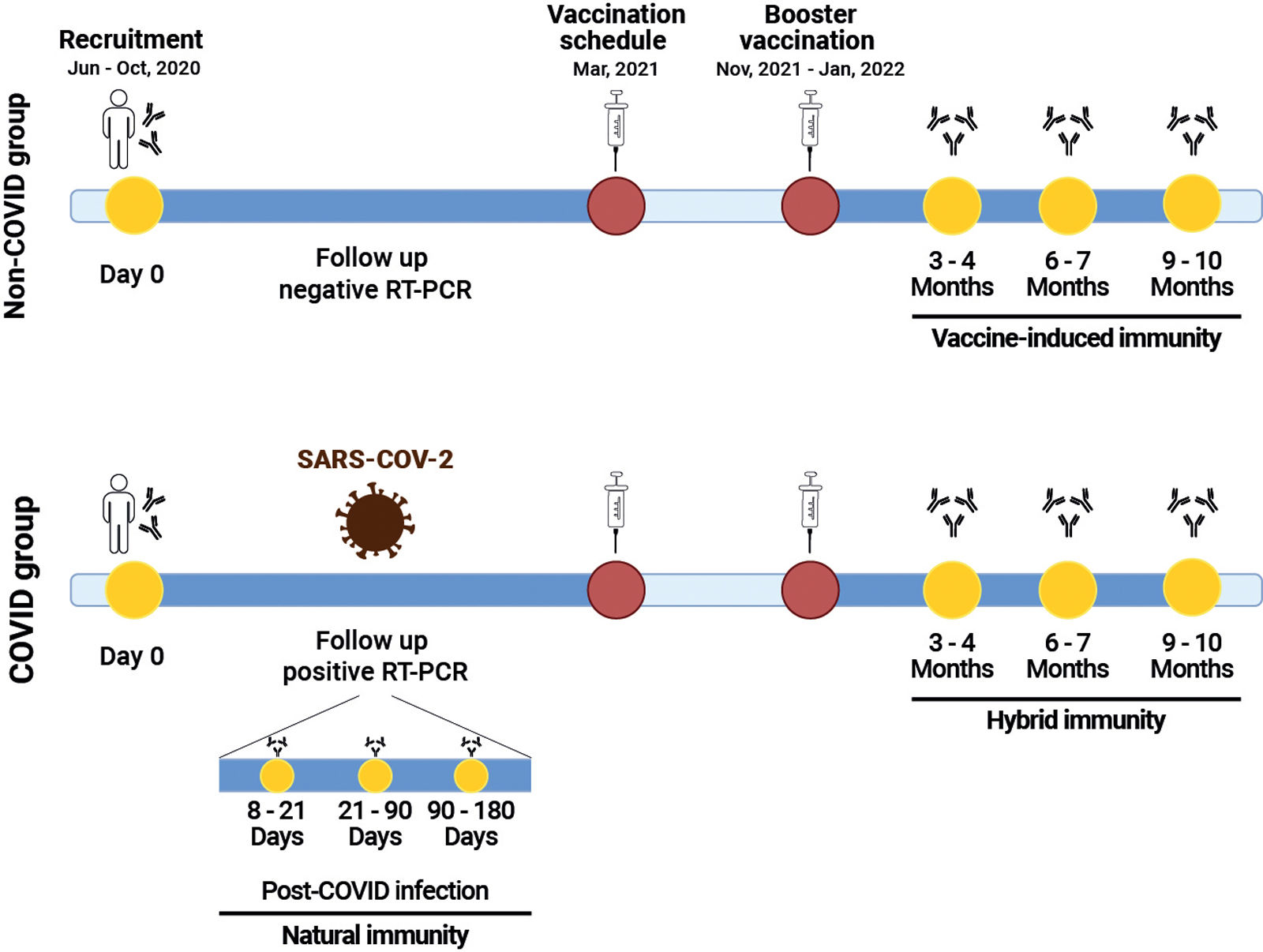

Materials and methodsWe conducted an observational prospective cohort study, including 50 HCWs without prior or current evidence of overt autoimmunity, as determined through self-report and verification of their electronic medical records at baseline. The study was carried out at the high complexity center, University Hospital Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, in Colombia and included participants with administrative roles, direct patient contact, and blended responsibilities. This study was approved by the Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá Ethics Committee (CCEI-12183-2020 and CCEI-13882-2022). The participants were recruited between June and October 2020 and were followed until October 2022. Participants were divided into two groups based on SARS-CoV-2 infection status, confirmed by RT-PCR: (1) The non-COVID group, comprising participants without SARS-CoV-2 infection (n:17) and (2) the COVID group, consisting participants with SARS-CoV-2 positivity during the follow-up period (n:33). Both groups received a primary vaccination schedule with two doses of BNT162b2 (completed in March 2021) and then a booster dose of mRNA-1273 (between November 2021 and January 2022) (Fig. 1). Medical records were reviewed using a questionnaire designed to gather sociodemographic information, clinical characteristics and symptoms, both at study entry and during follow-up. A total of 184 serum samples corresponding to non-COVID, pre-COVID, 8–21, 22–90- and 91–180 days post-infection, and post-boost vaccination were evaluated. We assessed a panel of 8 autoantibodies, including IgM rheumatoid factor (RF), IgG anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide third generation (CCP3), IgM and IgG anti-cardiolipin antibodies (ACAs), IgM and IgG anti-β2 glycoprotein-1 (β2GP1) antibodies, IgG anti-thyroglobulin (Tg) antibodies and anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies by enzyme-linked-immunosorbent assay-ELISA (Werfen, Barcelona-Spain) and other 17 autoantibodies including anti-dsDNA, anti-AMA M2, anti-CENPB, anti-Histones, anti-Jo1, anti-Ku, anti-Mi2, anti-nucleosomes, anti-PCNA, anti-PM-Scl, anti-P0 (RPP), anti-Scl70, anti-SmD1, anti-SS-A/Ro52, anti-SS-A/Ro60, anti-SS-B/La, and anti-U1-SnRNP were evaluated by IMTEC-ANA-LIA Maxx (Human diagnostics, Magdeburg-Germany). In addition, human IgG antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 were detected using a Euroimmun ELISA kit (Euroimmun, Lübeck-Germany). Univariate descriptive statistics were performed. Categorical variables were analyzed using frequencies, and continuous quantitative variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). The Mann–Whitney U-test or Fisher exact tests were used based on the results. None of the included parameters were subjected to statistical transformation, normalization, or data imputation. The analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2 with the Arsenal package.

Study timeline. Participants were recruited between June and October 2020 and followed until October 2022. They were classified into two groups based on SARS-CoV-2 infection status: the non-COVID group and the COVID group. Both groups received a primary vaccination schedule with two doses of BNT162b2, completed, followed by a booster dose of mRNA-1273. The presence of autoantibodies was assessed at the time points indicated in yellow.

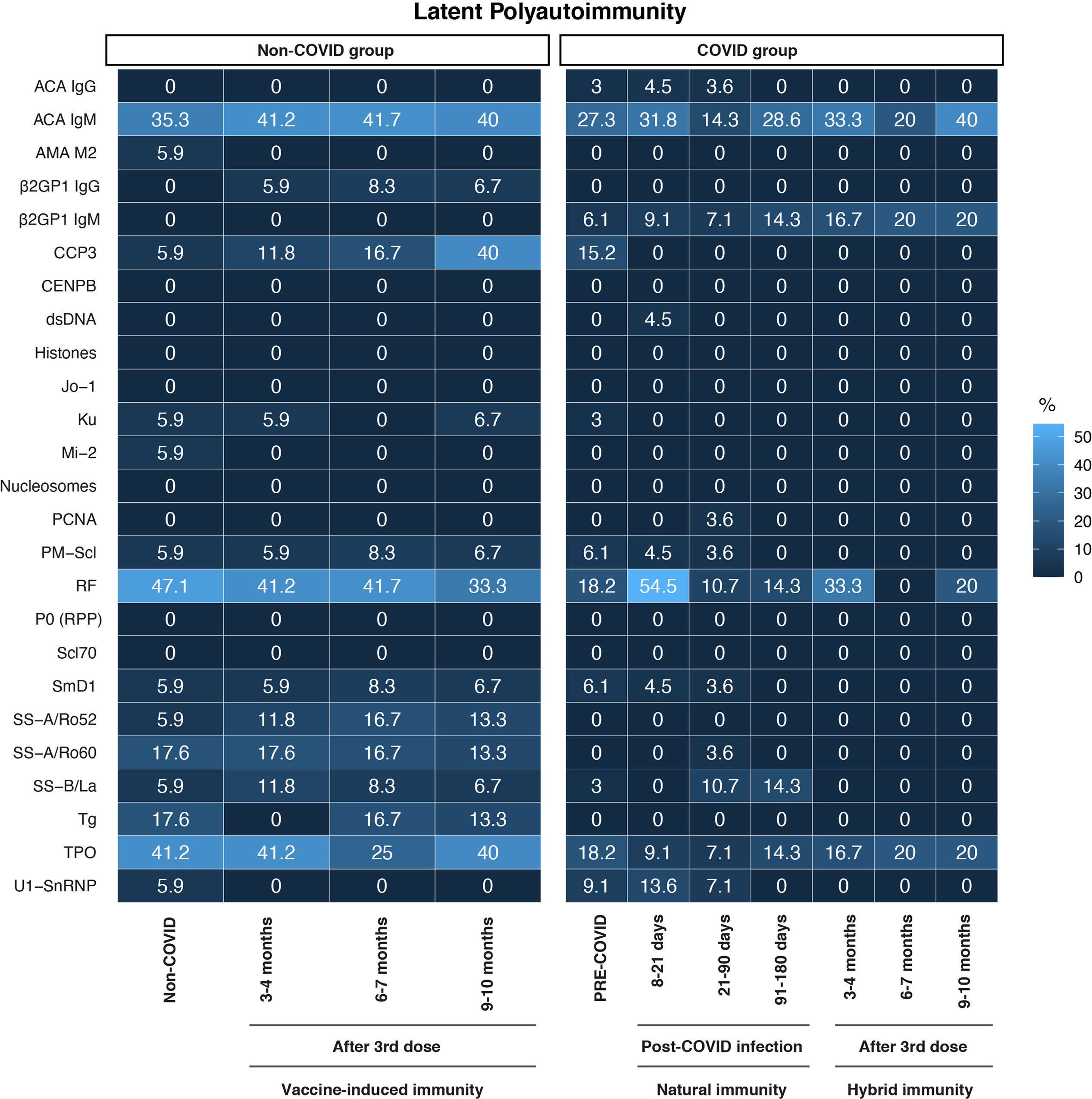

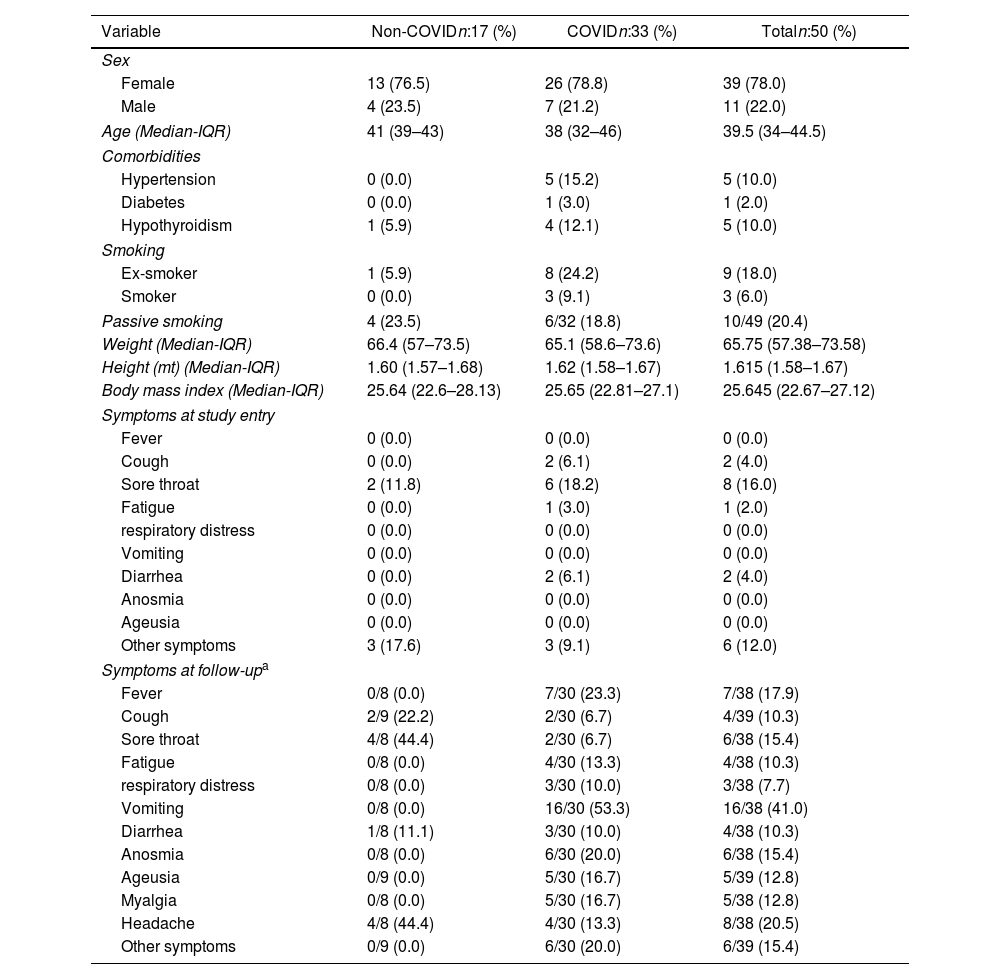

General characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. At the start of the study, all participants in the non-COVID and the pre-COVID groups were negative for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR and for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies by ELISA. Most of the participants were women (n:39, 78%), with a median age of 39.5 years. Most workers had patient-facing roles (63.8%), followed by administrative roles (19.1%), and blended roles (17%). Hypertension, hypothyroidism, and diabetes were the most frequently reported comorbidities. In contrast, none of the participants reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, asthma, immunosuppression, or cancer among the evaluated comorbidities. Throughout both the initial assessment and follow-up, sore throat, vomiting, headache, fever, and anosmia emerged as the predominant symptoms within the cohort (Table 1). Frequencies of autoantibodies in HCWs are shown in Fig. 2. The assessment of the presence of the 25 autoantibodies associated with latent rheumatic, thyroid, and phospholipid autoimmunity, did not yield significant differences between the studied groups (Fisher's exact test, P>0.050). A discernible trend emerged, indicating heightened occurrences of anti-CCP3 antibody positivity (40%) within the non-COVID group after seven months of booster vaccination, along with an elevation in RF antibody levels (54.5%) among participants infected within an 8–21-day timeframe post-infection. Natural infection with SARS-CoV-2, vaccination, or hybrid immunity against this virus was not associated with the development of new-onset latent autoimmunity in this population. Interestingly, anti-TPO and IgM ACAs exhibited a high prevalence across all studied groups, regardless of their subdivision, compared to the other autoantibodies evaluated.

General characteristics of 50 HCWs categorized into two groups based on their COVID-19 history.

| Variable | Non-COVIDn:17 (%) | COVIDn:33 (%) | Totaln:50 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 13 (76.5) | 26 (78.8) | 39 (78.0) |

| Male | 4 (23.5) | 7 (21.2) | 11 (22.0) |

| Age (Median-IQR) | 41 (39–43) | 38 (32–46) | 39.5 (34–44.5) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 0 (0.0) | 5 (15.2) | 5 (10.0) |

| Diabetes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 (5.9) | 4 (12.1) | 5 (10.0) |

| Smoking | |||

| Ex-smoker | 1 (5.9) | 8 (24.2) | 9 (18.0) |

| Smoker | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.1) | 3 (6.0) |

| Passive smoking | 4 (23.5) | 6/32 (18.8) | 10/49 (20.4) |

| Weight (Median-IQR) | 66.4 (57–73.5) | 65.1 (58.6–73.6) | 65.75 (57.38–73.58) |

| Height (mt) (Median-IQR) | 1.60 (1.57–1.68) | 1.62 (1.58–1.67) | 1.615 (1.58–1.67) |

| Body mass index (Median-IQR) | 25.64 (22.6–28.13) | 25.65 (22.81–27.1) | 25.645 (22.67–27.12) |

| Symptoms at study entry | |||

| Fever | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cough | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.1) | 2 (4.0) |

| Sore throat | 2 (11.8) | 6 (18.2) | 8 (16.0) |

| Fatigue | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| respiratory distress | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vomiting | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.1) | 2 (4.0) |

| Anosmia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ageusia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other symptoms | 3 (17.6) | 3 (9.1) | 6 (12.0) |

| Symptoms at follow-upa | |||

| Fever | 0/8 (0.0) | 7/30 (23.3) | 7/38 (17.9) |

| Cough | 2/9 (22.2) | 2/30 (6.7) | 4/39 (10.3) |

| Sore throat | 4/8 (44.4) | 2/30 (6.7) | 6/38 (15.4) |

| Fatigue | 0/8 (0.0) | 4/30 (13.3) | 4/38 (10.3) |

| respiratory distress | 0/8 (0.0) | 3/30 (10.0) | 3/38 (7.7) |

| Vomiting | 0/8 (0.0) | 16/30 (53.3) | 16/38 (41.0) |

| Diarrhea | 1/8 (11.1) | 3/30 (10.0) | 4/38 (10.3) |

| Anosmia | 0/8 (0.0) | 6/30 (20.0) | 6/38 (15.4) |

| Ageusia | 0/9 (0.0) | 5/30 (16.7) | 5/39 (12.8) |

| Myalgia | 0/8 (0.0) | 5/30 (16.7) | 5/38 (12.8) |

| Headache | 4/8 (44.4) | 4/30 (13.3) | 8/38 (20.5) |

| Other symptoms | 0/9 (0.0) | 6/30 (20.0) | 6/39 (15.4) |

Heatmap of autoantibody frequency. Frequency of autoantibodies in HCWs without a history of COVID-19 infection and those with COVID-19 during the study. Both groups received two doses of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine and a booster of mRNA-1273. Non-COVID Group (n:17) after 2-months (n:17), 4 months (n:12) and 7 months (n:15) post-boost. COVID group: pre-COVID (n:33), 8–21 days (n:22), 21–90 days (n:28), 91–180 days (n:7) post-infection, and after 3–4 months (n:6), 6–7 months (n:5) and 9–10 months (n:5) post-boost. Differences in positivity among the autoantibodies were evaluated by Fisher's exact test. No statistically significant differences were observed.

The lack of autoantibodies after vaccination and/or COVID-19 infection could be associated with HCWs exhibiting mild symptoms of COVID-19. Clinical profiling of positive cases among HCWs from the same institution revealed that 82% were classified as mild disease [10]. In contrast, latent autoimmunity is mainly observed in patients with severe COVID-19 without evidence of overt autoimmunity [7]. For instance, a diverse range of autoantibodies has been identified in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, including antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-TPO antibodies, RF, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, ACAs, and anti-β2GP1 antibodies. Additionally, autoantibodies targeting immunomodulatory proteins, such as cytokines, chemokines, complement components, and cell surface proteins, have also been detected. These autoantibodies have been associated with the severity of COVID-19 and long COVID [7,9]. These newly induced autoantibodies are triggered by severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, suggesting that mechanisms such as molecular mimicry [11], epitope spreading [12] and a robust inflammatory response may contribute to a breakdown in immune tolerance and activation of extrafollicular B cells producing autoantibodies [13].

A study conducted in HCWs found that common autoantibodies (i.e., anti-MPO, anti-PR3, anti-CCP, anti-β2GPI, ACA, ASMA), showed a slight increase when comparing the period before vaccine inoculation with the period after receiving two doses of mRNA vaccines (mRNA BNT162b2 and mRNA 1273), although this increase was not statistically significant. Studies have shown that ANAs are increased after mRNA vaccination correlating directly with the number of vaccine doses. However, their pattern distribution and titers were not statistically significant [14]. The first study that reported the presence of ANAs after COVID-19 was Zhou et al. [15], who showed its presence in 50% of the severe and critical forms of COVID-19. Moreover, other authors have found that patients with positive ANAs are more likely to develop critical illness [7]. While autoantibodies may contribute to the development of severe disease, they are not the sole determining factor. Other variables, such as age, sex, ethnicity, obesity, and pre-existing conditions, also play a critical role in disease severity [16]. The development of ANAs in COVID-19 patients involves mechanisms similar to those seen in systemic lupus erythematosus, particularly the activation of TLR7, TLR9, and B cells through the extrafollicular pathway [17]. The correlation among ANAs, COVID-19 severity, and the occurrence of long COVID emphasizes the important role of ANAs in COVID-19 [18]. All these results strengthen the absence of ANAs in our cohort.

Since anti-CCP and RF antibodies showed the only upward trends after vaccination and infection, respectively, albeit without significance in our cohort, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) could potentially develop in these individuals in the future. However, previous studies have shown that positive cases of anti-CCP antibodies are higher in severe COVID-19 compared to mild patients [18]. Additionally, elevated levels of RF have been reported in severe cases, in contrast to moderate and asymptomatic forms of the disease [19]. Furthermore, other studies have shown no association between COVID-19 illness and the subsequent development of RA-related autoimmunity, nor the emergence of RA signs or symptoms in at-risk individuals [20]. Consistent with our results, levels of anti-CCP and RF antibodies did not show significant changes after COVID-19 vaccination in HCW from Italy [14]. However, a few case reports have described new-onset seropositive RA following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination [21,22]. The development of RA, along with the production of anti-CCP and RF antibodies, is influenced by various factors. These include genetic components, such as the shared epitope, specific HLA-DRB1 alleles, and polymorphisms in peptidyl arginine deiminase 4, as well as environmental factors like smoking. Consequently, the presence of anti-CCP antibodies in COVID-19 patients may predict the potential development of RA, particularly in individuals with a genetic predisposition, including those carrying specific HLA-DRB1 alleles [23]. Moreover, the persistent inflammation and hyper-activation of the immune system with other predisposing conditions, such as age, comorbidities, and genetic factors could play an important role in the emergence of latent autoimmunity that through years could evolve to overt autoimmunity. On the other hand, we observed elevated levels of anti-TPO antibodies in the evaluated groups, indicating that latent thyroid autoimmunity is not uncommon in our population. A study conducted by Rodríguez et al [24]. reported that 15.3% of individuals exhibited this condition without clinical manifestations, consistent with findings from other countries, where prevalence rates reach up to 26.4%. In addition, most studies report a prevalence of ACAs of any isotype below 10%, except in studies involving individuals at the extremes of life [25]. ACA levels can transiently increase during various infections [26]. Notably, all participants in this study were HCWs who, despite testing negative for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of enrollment, were frequently exposed to a wide range of pathogens due to the nature of their profession. However, when comparing the prevalence of ACAs before and after vaccination, no significant changes were observed. This finding is consistent with a previous study on staff members, which reported no alterations in anti-phospholipid antibody titers following the administration of BNT162b2 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [27]. However, the evaluation of these autoantibodies is important because they represent a significant risk factor for the development of ADs.

The limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Autoimmunity was assessed through self-report and further verification of the participant's electronic medical records. This approach prioritized specificity over sensitivity, which may have led to underreporting, particularly among individuals who avoid seeking medical attention or those with symptoms suggestive of autoimmunity but without a confirmed diagnosis. Additionally, variability in the prevalence of certain autoantibodies was observed among the studied groups, despite the absence of statistically significant differences. This fluctuation may be attributed to the sample size of each group and changes in participant composition over time. Future studies with larger, longitudinally consistent cohorts are needed to better assess the stability and clinical relevance of latent autoimmunity prevalence in this context.

Further research is necessary to elucidate the link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination with the development of latent and overt autoimmunity. Moreover, our results confirm the safety of COVID-19 vaccines, as well as suggest specific health conditions in reported cases of autoimmunity after COVID-19 vaccination.

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization and study design: DMM, YA-A, CR-S. Participant inclusion and clinical data collection: NC and JQ. Experimental procedures: DMM, YA-A, CR-S. Statistical analysis: MR. All authors contributed to the writing, review, and/or editing of the manuscript prior to submission. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical considerationsThis study involves human participants and has been approved by the Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá Ethics Committee (CCEI-12183-2020 and CCEI-13882-2022). Participants provided their informed consent before participating in the study.

FundingThis work was supported by Universidad del Rosario ABN-011 and Universidad de los Andes – Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, Colombia.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

To all HCWs who accepted to participate in this study.