Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in young people from urban neighbourhoods in Latin America (OLA)

Más datosMental disorders, including depression and anxiety, present a substantial burden for adolescents and young adults in Latin America, where socio-economic challenges hinder recovery. Perceived social support (PSS) is a potential protective factor, yet its role in the recovery of common mental disorders in this population is underexplored.

MethodsA prospective cohort study (2021–2024) followed adolescents (15–16 years) and young adults (20–24 years) in disadvantaged neighborhoods of Bogotá, Buenos Aires, and Lima. Depression and anxiety symptoms (PHQ-8, GAD-7) and PSS (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support) were assessed at baseline, 12, and 24 months. A longitudinal multivariable model using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) examined associations between PSS and recovery, adjusting for sociodemographic and psychosocial factors.

ResultsAmong 1437 participants, 70.5% completed the 24-month follow-up. Higher PSS was associated with greater recovery. Recovery for depressive and anxiety symptoms was statistically significantly higher among participants reporting medium (adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR): 2.77; 95% CI: 1.70–4.51) and high (aOR: 5.05; 95% CI: 3.03–8.43) levels of total PSS compared with those with low PSS. Support from family and friends were both statistically significantly associated with recovery. After adjustment, the odds of recovery were elevated for people with medium (aOR: 2.58; 95% CI: 1.71–3.89) and high (aOR: 3.13; 95% CI: 2.06–4.74) levels of support from friends. Interaction analyses revealed that age, resilience and employment modified these associations; with stronger effects in younger participants (15–16 vs. 20–24 years), those employed, and those with high levels of resilience (≥28).

ConclusionSocial support, especially from family and friends, enhances recovery from depression and anxiety, with resilience, employment and age modulating these effects. Strengthening support networks and resilience-building interventions may improve mental health outcomes in vulnerable youth.

Los trastornos mentales, como la depresión y la ansiedad, representan una carga significativa para los adolescentes y adultos jóvenes en América Latina, donde los desafíos socioeconómicos dificultan la recuperación. El apoyo social percibido (ASP) es un potencial factor protector; sin embargo, su papel en la recuperación de los trastornos mentales más comunes en esta población ha sido poco explorado.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio de cohorte prospectivo (2021-2024) con adolescentes (15-16 años) y adultos jóvenes (20-24 años) de barrios desfavorecidos en Bogotá, Buenos Aires y Lima. Se evaluaron los síntomas de depresión y ansiedad mediante el PHQ-8 y el GAD-7, así como el ASP a través de la Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido al inicio del estudio, a los 12 y 24 meses. Se empleó un modelo multivariable longitudinal con Ecuaciones de Estimación Generalizada para analizar la asociación entre el ASP y la recuperación, ajustando por factores sociodemográficos y psicosociales.

ResultadosDe los 1.437 participantes, el 70,5% completó el seguimiento de 24 meses. Un mayor ASP se asoció con una mayor recuperación de los síntomas depresivos y ansiosos. En comparación con los participantes con bajos niveles de ASP, aquellos con niveles medios (ORa: 2,77; IC 95%: 1,70-4,51) y altos (ORa: 5,05; IC 95%: 3,03-8,43) mostraron una recuperación significativamente mayor. El apoyo familiar y de amigos se asoció de manera significativa con la recuperación. En particular, el apoyo de amigos se relacionó con mayores probabilidades de recuperación en personas con niveles medios (aOR: 2,58; IC 95%: 1,71-3,89) y altos (aOR: 3,13; IC 95%: 2,06-4,74). Los análisis de interacción indicaron que la edad, la resiliencia y el empleo modificaban estas asociaciones, con efectos más pronunciados en los participantes más jóvenes (15-16 vs. 20-24 años), aquellos con empleo y quienes presentaban altos niveles de resiliencia (≥ 28).

ConclusiónEl apoyo social, particularmente de familiares y amigos, favorece la recuperación de la depresión y la ansiedad. Además, la resiliencia, el empleo y la edad modulan estos efectos. Fortalecer las redes de apoyo e implementar intervenciones dirigidas a aumentar la resiliencia podría mejorar los resultados de salud mental en los jóvenes.

Mental disorders have become a significant and global health burden in recent years.1 Recent research has revealed a stark increase in mental health problems for children and young people, with 48.5% of all mental health disorders beginning before 18 years old,2 and concerning trends in the prevalence and impact amongst young people over the last decade.3,4 According to the World Health Organization, one in seven adolescents aged 10–19 experiences a mental disorder, contributing to 13% of the global disease burden in this age group.5 The most common mental disorders among adolescents are depression and anxiety.6,7 These conditions have long-lasting effects, often carrying over into adulthood, where they impair both physical and mental health and limit opportunities for achieving fulfilling lives.8

In South American countries, the prevalence of depression and anxiety among young people is a growing concern, exacerbated by socio-economic challenges and cultural factors.9 Approximately 16 million adolescents in the region live with mental disorders, with estimates indicating that between 17% and 26% of youth experience symptoms of depression or anxiety, depending on the country.10 Factors like poverty, violence, and limited access to mental health and social services often exacerbate these mental health issues, making recovery more challenging.11,12 Despite these adversities, many young people use different resilience strategies and draw on different forms of perceived social support to cope with their mental distress.13 In particular, emotional support from family and friends plays a crucial role in fostering resilience and recovery, as strong social connections can provide encouragement and practical assistance during difficult times.13,14 However, cultural stigma surrounding mental health amongst young people in South America often prevents open discussions about these issues, leading to underreporting and inadequate treatment for those in need.15

Social support is believed to safeguard mental health by providing networks of trust that can provide direct emotional, psychological, and practical resources and by acting as a buffer against stressful situations indirectly.16 Social support encompasses various dimensions, including emotional support (such as offering encouragement), practical help (like assisting with household chores), and informational aid (for instance, informing someone about a job opening) received from others.17 Several studies show that individuals with strong social support networks experience reduced levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, highlighting the vital role these connections play in promoting psychological well-being.18–20

To the best of our knowledge, no longitudinal study has been conducted to examine the association between perceived social support and the recovery or persistence of depression and anxiety in adolescents and young adults in Latin America. Most existing research has focused on cross-sectional analyses, limiting our understanding of how social support influences mental health outcomes over time.21 In a previous study, we found an association between medium and high levels of perceived social support and reduced anxiety and depression symptoms at baseline.22 Here, we examine the role of perceived social support in the recovery from depressive and anxiety symptoms from baseline until 24 months among adolescents and young adults in three Latin American cities: Bogotá (Colombia), Buenos Aires (Argentina), and Lima (Peru).

Our main research question was whether perceived social support from friends, family and significant others was longitudinally associated with recovery from depression over 24 months. We hypothesized that participants with strong perceived social support would have higher odds of recovery compared to those with weaker or no perceived social support.

MethodsStudy designThis is a prospective longitudinal cohort study conducted between April 2021 and July 2024 as part of the “Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in adolescents and young adults living in neighborhoods in Latin America (OLA)” Research Program.23 In this study, adolescents and young adults who met cut-offs for clinically-relevant symptoms of depression and anxiety at baseline were followed-up to assess recovery at 12 and 24 months.

SettingThis study was carried out in Bogotá (Colombia), Buenos Aires (Argentina), and Lima (Peru). Participant recruitment for baseline assessments occurred between April 2021 and November 2022, with 12-month follow-ups conducted from May 2022 to November 2023, and 24-month follow-ups taking place from June 2023 to July 2024.

ParticipantsAt baseline, we recruited two groups of young people—adolescents (aged 15–16) and young adults (aged 20–24)—from the most disadvantaged 50% of neighborhoods in each city, according to a predefined sampling strategy23 using the Human Development Index24 in Bogotá and Lima, and the Unsatisfied Basic Needs Index in Buenos Aires. Participants were invited through educational institutions and community organizations to take part in the study. Our exclusion criteria were: (1) a diagnosis of a serious mental disorder (such as psychosis, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia), (2) a diagnosis of intellectual disability, (3) illiteracy, and (4) inability to provide informed consent for young adults or assent for adolescents. For the remaining participants, we assessed levels of anxiety and depression at baseline using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8), respectively.25,26 Participants who scored 10 or more on either scale were defined as having clinically relevant symptomatology consistent with a diagnosable disorder, while those who scored less than 10 were considered controls. In the present study, only those with clinically relevant symptomatology at baseline were followed-up longitudinally. The study's context, details and procedures have been published elsewhere.27

OutcomeTo assess symptoms of anxiety and depression at 12 and 24 months, participants completed the GAD-7 and PHQ-825,26 again. Symptomatic recovery was determined dichotomously based on GAD and PHQ scores: recovery was defined as a score less than 10, while non-recovery was defined as a score of 10 or more.

ExposurePerceived social support was assessed using the self-reported 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support,28 which evaluates support from three sources: family, friends, and significant others. Each subscale comprises four items, rated on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In this study, the score for each subscale was calculated as the mean of the participant's responses to the four items. The overall scale score was derived from the mean of all 12 items. Scores were categorized into low (1–2.9), moderate (3–5), and high (5.1–7) levels of perceived support.28

ConfoundersWe included the following confounding variables: baseline symptom severity (one variable: GAD score ≥15 and another variable: PHQ-8 score ≥15), age at baseline (categorized as adolescents aged 15–16 years and young adults aged 20–24 years), marital status (single/not single), current employment status (yes/no), and history of mental health problems. The latter was assessed at baseline focusing on low mood (defined as feelings of sadness that are more intense than usual and persist for more than 30 consecutive days) and anxiety (defined as feelings of distress that are more intense than usual and persist for more than 30 consecutive days). Resilience was measured using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10).29 The cut-off points used to define low (≤21), medium22–27 and high (≥28) resilience were not based on previously validated thresholds. Instead, they were defined specifically for this study based on the distribution of resilience scores in our sample, with the highest tertile representing high resilience. This exploratory approach was intended to facilitate the interpretation of the interaction analyses, although we acknowledge that the choice of thresholds was arbitrary. Engagement with social media was assessed using an adapted version of the Multidimensional Facebook Intensity Scale.30 Additionally, a life events questionnaire, adapted from the Adolescent Appropriate Life Events Scale,31 was included. Finally, self-developed scales were used to measure engagement in sports and arts activities over the past 30 days.

Data analysisDescriptive analysisDescriptive analyses were conducted using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, as well as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for discrete numerical variables according to the follow-up time points. Subsequently, a stratified analysis was performed on anxiety and depression symptoms, assessed through GAD-7 and PHQ-8 scores, based on the different subscales of perceived social support (family support, friend support, and significant other support).

Multivariable analysisTo evaluate the association between social support subscales and the recovery from depression and anxiety, longitudinal models were constructed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) Logistic Regression. For each PSS definition, we ran both a univariable model and a multivariable model, adjusted for baseline social support dimensions, baseline symptoms severity, age at baseline, history of mental health problems, marital status, current employment, resilience, engagement in sports and arts activities over the past 30 days, life events experienced in recent years, and social media usage scores. Odds ratios (ORs) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated.

Interactions between social support subscales and sociodemographic variables—such as age, marital status, current employment, and resilience—were examined in a multivariable model to identify potential effect modifiers in the relationship between social support and recovery. The relevance of these interactions was assessed based on the interpretation of confidence intervals using Wald test and their alignment with the study's research question.

Since the missing values for the variables considered in the analysis did not exceed 5%, no data imputation was performed (see Annex 3). This proportion falls below the widely accepted threshold in methodological literature, which considers less than 5% missing data to represent a minimal loss. In such cases, the potential impact on estimates is generally limited, and the need for imputation becomes debatable. In fact, performing imputation when missingness is low may introduce unnecessary analytical complexity and potentially increase uncertainty. Data processing and statistical analyses were conducted in R via the RStudio interface.32,33

EthicsThe study protocol for the OLA project and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Buenos Aires on (02-10-2020), of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana on November 20, 2020 (FM-CIE-1138-20), and of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia on November 16, 2020 (Constancia 581-33-20). In addition, it was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Queen Mary University of London on November 16, 2020 (QMERC2020/02).

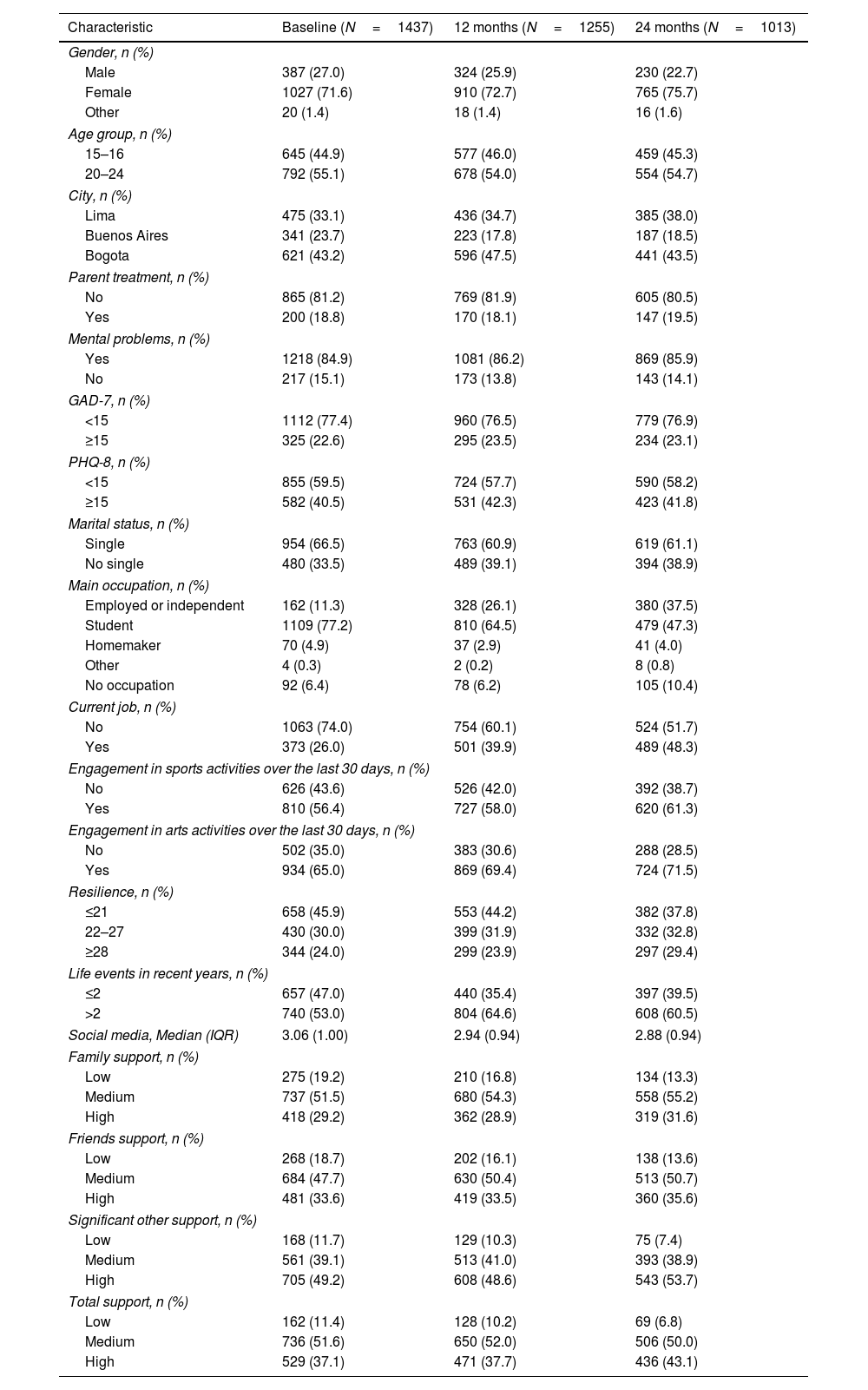

ResultsSample descriptionTable 1 provides a summary of the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants at baseline (N=1437), 12 months (N=1255; 87.3%), and 24 months (N=1013; 70.5%). The gender distribution showed that the majority of participants were female across all time points, increasing from 71.6% at baseline to 75.7% at 24 months, while males were more likely to be lost to follow-up (decreasing from 27.0% to 22.7%) over the same period. A small percentage (1.4–1.6%) identified as “Other” genders. Participants aged 20–24 years represented the largest age group, constituting 55.1% at baseline, with similar distributions observed at 12 and 24 months. Regarding baseline symptom severity, 22.6% had a GAD-7 score ≥15, while 40.5% had a PHQ-8 score ≥15. Engagement in sports and arts activities over the past 30 days showed an increasing trend in participation over time. At baseline, 56.4% participated in sports, rising to 58.0% at 12 months and 61.3% at 24 months. Similarly, arts participation increased from 65.0% at baseline to 69.4% at 12 months and 71.5% at 24 months. Resilience levels also changed over time, with the proportion of participants with low resilience (≤21) decreasing from 45.9% at baseline to 44.2% at 12 months and 37.8% at 24 months. Social support levels showed some variations across different time points. High family support was reported by 29.2% at baseline, 28.9% at 12 months, and 31.6% at 24 months. High friend support was reported by 33.6% at baseline, 33.5% at 12 months, and 35.6% at 24 months. High support from a significant other was reported by 49.2% at baseline, slightly decreasing to 48.6% at 12 months, before rising to 53.7% at 24 months.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants at baseline and during follow-up.

| Characteristic | Baseline (N=1437) | 12 months (N=1255) | 24 months (N=1013) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 387 (27.0) | 324 (25.9) | 230 (22.7) |

| Female | 1027 (71.6) | 910 (72.7) | 765 (75.7) |

| Other | 20 (1.4) | 18 (1.4) | 16 (1.6) |

| Age group, n (%) | |||

| 15–16 | 645 (44.9) | 577 (46.0) | 459 (45.3) |

| 20–24 | 792 (55.1) | 678 (54.0) | 554 (54.7) |

| City, n (%) | |||

| Lima | 475 (33.1) | 436 (34.7) | 385 (38.0) |

| Buenos Aires | 341 (23.7) | 223 (17.8) | 187 (18.5) |

| Bogota | 621 (43.2) | 596 (47.5) | 441 (43.5) |

| Parent treatment, n (%) | |||

| No | 865 (81.2) | 769 (81.9) | 605 (80.5) |

| Yes | 200 (18.8) | 170 (18.1) | 147 (19.5) |

| Mental problems, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 1218 (84.9) | 1081 (86.2) | 869 (85.9) |

| No | 217 (15.1) | 173 (13.8) | 143 (14.1) |

| GAD-7, n (%) | |||

| <15 | 1112 (77.4) | 960 (76.5) | 779 (76.9) |

| ≥15 | 325 (22.6) | 295 (23.5) | 234 (23.1) |

| PHQ-8, n (%) | |||

| <15 | 855 (59.5) | 724 (57.7) | 590 (58.2) |

| ≥15 | 582 (40.5) | 531 (42.3) | 423 (41.8) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 954 (66.5) | 763 (60.9) | 619 (61.1) |

| No single | 480 (33.5) | 489 (39.1) | 394 (38.9) |

| Main occupation, n (%) | |||

| Employed or independent | 162 (11.3) | 328 (26.1) | 380 (37.5) |

| Student | 1109 (77.2) | 810 (64.5) | 479 (47.3) |

| Homemaker | 70 (4.9) | 37 (2.9) | 41 (4.0) |

| Other | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 8 (0.8) |

| No occupation | 92 (6.4) | 78 (6.2) | 105 (10.4) |

| Current job, n (%) | |||

| No | 1063 (74.0) | 754 (60.1) | 524 (51.7) |

| Yes | 373 (26.0) | 501 (39.9) | 489 (48.3) |

| Engagement in sports activities over the last 30 days, n (%) | |||

| No | 626 (43.6) | 526 (42.0) | 392 (38.7) |

| Yes | 810 (56.4) | 727 (58.0) | 620 (61.3) |

| Engagement in arts activities over the last 30 days, n (%) | |||

| No | 502 (35.0) | 383 (30.6) | 288 (28.5) |

| Yes | 934 (65.0) | 869 (69.4) | 724 (71.5) |

| Resilience, n (%) | |||

| ≤21 | 658 (45.9) | 553 (44.2) | 382 (37.8) |

| 22–27 | 430 (30.0) | 399 (31.9) | 332 (32.8) |

| ≥28 | 344 (24.0) | 299 (23.9) | 297 (29.4) |

| Life events in recent years, n (%) | |||

| ≤2 | 657 (47.0) | 440 (35.4) | 397 (39.5) |

| >2 | 740 (53.0) | 804 (64.6) | 608 (60.5) |

| Social media, Median (IQR) | 3.06 (1.00) | 2.94 (0.94) | 2.88 (0.94) |

| Family support, n (%) | |||

| Low | 275 (19.2) | 210 (16.8) | 134 (13.3) |

| Medium | 737 (51.5) | 680 (54.3) | 558 (55.2) |

| High | 418 (29.2) | 362 (28.9) | 319 (31.6) |

| Friends support, n (%) | |||

| Low | 268 (18.7) | 202 (16.1) | 138 (13.6) |

| Medium | 684 (47.7) | 630 (50.4) | 513 (50.7) |

| High | 481 (33.6) | 419 (33.5) | 360 (35.6) |

| Significant other support, n (%) | |||

| Low | 168 (11.7) | 129 (10.3) | 75 (7.4) |

| Medium | 561 (39.1) | 513 (41.0) | 393 (38.9) |

| High | 705 (49.2) | 608 (48.6) | 543 (53.7) |

| Total support, n (%) | |||

| Low | 162 (11.4) | 128 (10.2) | 69 (6.8) |

| Medium | 736 (51.6) | 650 (52.0) | 506 (50.0) |

| High | 529 (37.1) | 471 (37.7) | 436 (43.1) |

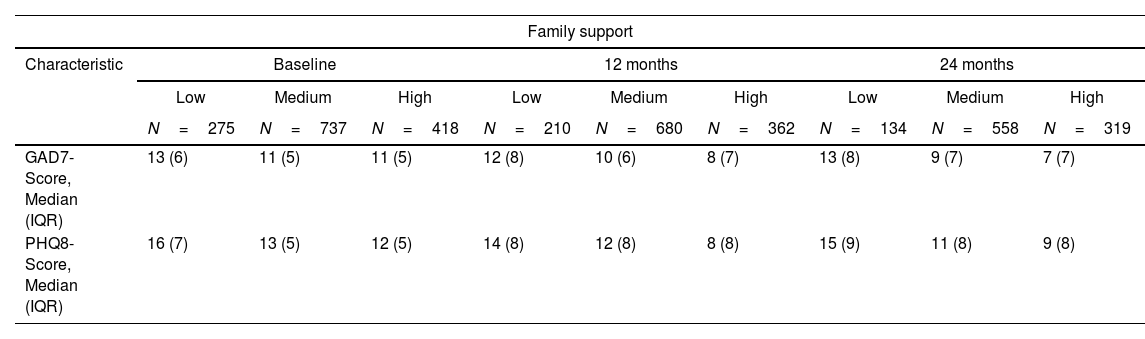

Table 2 presents the median values and interquartile ranges (IQR) of GAD-7 and PHQ-8 scores across different levels of perceived social support (high, medium, and low) for family, friends, and significant others at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. Higher levels of perceived support were consistently associated with lower GAD-7 and PHQ-8 scores. For family support, participants with high support had lower median scores (e.g., GAD-7: 11, PHQ-8: 12 at baseline) compared with those with low support (GAD-7: 13, PHQ-8: 16). Similar patterns were observed for friends and significant other support, where higher support consistently aligned with better mental health outcomes.

Median values of GAD and PHQ score according to type of perceived social support at baseline, 12 months and 24 months.

| Family support | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Baseline | 12 months | 24 months | ||||||

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | |

| N=275 | N=737 | N=418 | N=210 | N=680 | N=362 | N=134 | N=558 | N=319 | |

| GAD7-Score, Median (IQR) | 13 (6) | 11 (5) | 11 (5) | 12 (8) | 10 (6) | 8 (7) | 13 (8) | 9 (7) | 7 (7) |

| PHQ8-Score, Median (IQR) | 16 (7) | 13 (5) | 12 (5) | 14 (8) | 12 (8) | 8 (8) | 15 (9) | 11 (8) | 9 (8) |

| Friends Support | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Baseline | 12 months | 24 months | ||||||

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | |

| N=268 | N=684 | N=481 | N=202 | N=630 | N=419 | N=138 | N=513 | N=360 | |

| GAD7-Score, Median (IQR) | 13 (6) | 11 (5) | 11 (5) | 12 (6) | 9 (6) | 9 (7) | 13 (8) | 9 (7) | 8 (7) |

| PHQ8-Score, Median (IQR) | 15 (7) | 13 (5) | 13 (6) | 15 (9) | 12 (8) | 10 (8) | 15 (10) | 10 (8) | 9 (8) |

| Significant other support | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Baseline | 12 months | 24 months | ||||||

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | |

| N=168 | N=561 | N=705 | N=129 | N=513 | N=608 | N=75 | N=393 | N=543 | |

| GAD7-Score, Median (IQR) | 13 (6) | 11 (5) | 11 (5) | 12 (8) | 10 (6) | 9 (7) | 12 (10) | 10 (7) | 8 (7) |

| PHQ8-Score, Median (IQR) | 16 (8) | 14 (6) | 13 (5) | 15 (9) | 12 (8) | 10 (8) | 15 (10) | 11 (7) | 10 (8) |

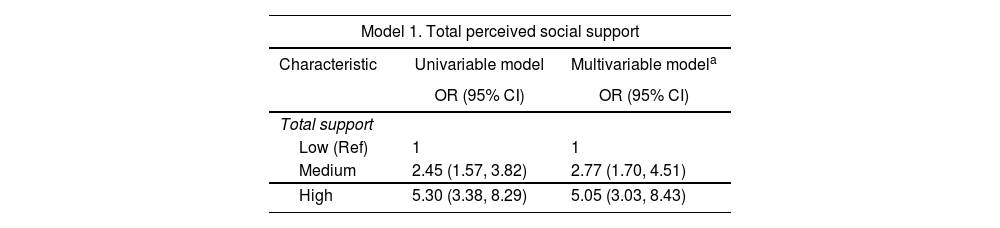

Table 3 presents the results of univariable and multivariable analyses of the association between perceived social support and recovery from anxiety and depression symptoms. In Model 1 of total perceived social support, higher levels of support were associated with greater odds of symptom recovery for those who reported medium and high levels of support compared with those who reported low total social support (medium support: OR: 2.45; 95% CI: 1.57–3.82; high support OR: 5.30; 95% CI: 3.38–8.29). These associations remained after adjusting for covariates in the multivariable model (medium support OR: 2.77; 95% CI: 1.70–4.51; high support OR: 5.05; 95% CI: 3.03–8.43), including age, history of mental health issues, baseline symptom severity (GAD-7 and PHQ-8 scores), marital status, current employment, resilience, recent engagement in sports or arts activities, significant life events, and social media usage.

Univariable and multivariable models (without interactions) examining the association between perceived social support and recovery from anxiety and depression symptoms.

| Model 1. Total perceived social support | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Univariable model | Multivariable modela |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Total support | ||

| Low (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 2.45 (1.57, 3.82) | 2.77 (1.70, 4.51) |

| High | 5.30 (3.38, 8.29) | 5.05 (3.03, 8.43) |

| Model 2. Perceived social support from friends, family, or significant others | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Univariable model | Multivariable modela |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Friends support | ||

| Low (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 2.10 (1.50, 2.94) | 2.27 (1.56, 3.31) |

| High | 2.52 (1.75, 3.62) | 2.58 (1.71, 3.89) |

| Family support | ||

| Low (Ref) | 1 | |

| Medium | 1.89 (1.34, 2.67) | 1.92 (1.32, 2.77) |

| High | 3.98 (2.72, 5.82) | 3.13 (2.06, 4.74) |

| Significant other support | ||

| Low (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 0.99 (0.64, 1.53) | 1.20 (0.76, 1.89) |

| High | 0.92 (0.59, 1.45) | 1.20 (0.74, 1.94) |

OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval.

Model adjusted for: Age (Baseline measurement), Mental problems (Ever) (Baseline measurement), GAD-7 – Severe symptoms (Baseline measurement), PHQ-8 – Severe symptoms (Baseline measurement), Marital status, Current job, Resilience, Engagement in sports activities over the past 30 days, Engagement in arts activities over the past 30 days, Life events in the last few years, Social media score. Total number of participants: 1266, total observations: 2219.

Model 2 evaluated the association between each dimension of perceived social support (friends, family, and significant other) and recovery (Table 3). In the univariable model, support from friends was associated with recovery, with medium (OR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.50–2.94) and high (OR: 2.52; 95% CI: 1.75–3.62) levels of support linked to greater odds of recovery compared with low support. These associations remained significant in the multivariable model, where medium (OR: 2.27; 95% CI: 1.56–3.31) and high (OR: 2.58; 95% CI: 1.71–3.89) levels of support continued to demonstrate higher odds of recovery.

Family support showed stronger associations in both models. In the univariable analysis, medium (OR: 1.89; 95% CI: 1.34–2.67) and high (OR: 3.98; 95% CI: 2.72–5.82) levels of family support were associated with recovery compared with low support. These relationships persisted in the multivariable model, with medium (OR: 2.58; 95% CI: 1.71–3.89) and high (OR: 3.13; 95% CI: 2.06–4.74) levels of family support continuing to show higher odds of recovery.

In contrast, support from a significant other did not show statistically significant associations in either model. For example, in our multivariable model there was no evidence that either medium (OR: 1.20; 95% CI: 0.76–1.89) or high (OR: 1.20; 95% CI: 0.74–1.94) levels of support from a significant other were associated with the likelihood of experiencing symptomatic recovery compared with those who perceived low support from a significant other.

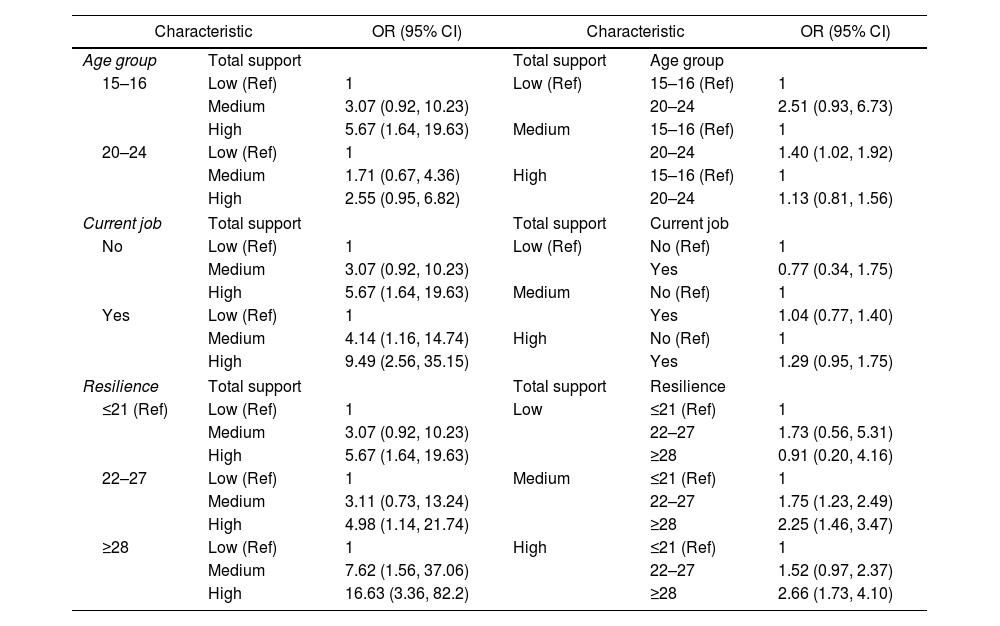

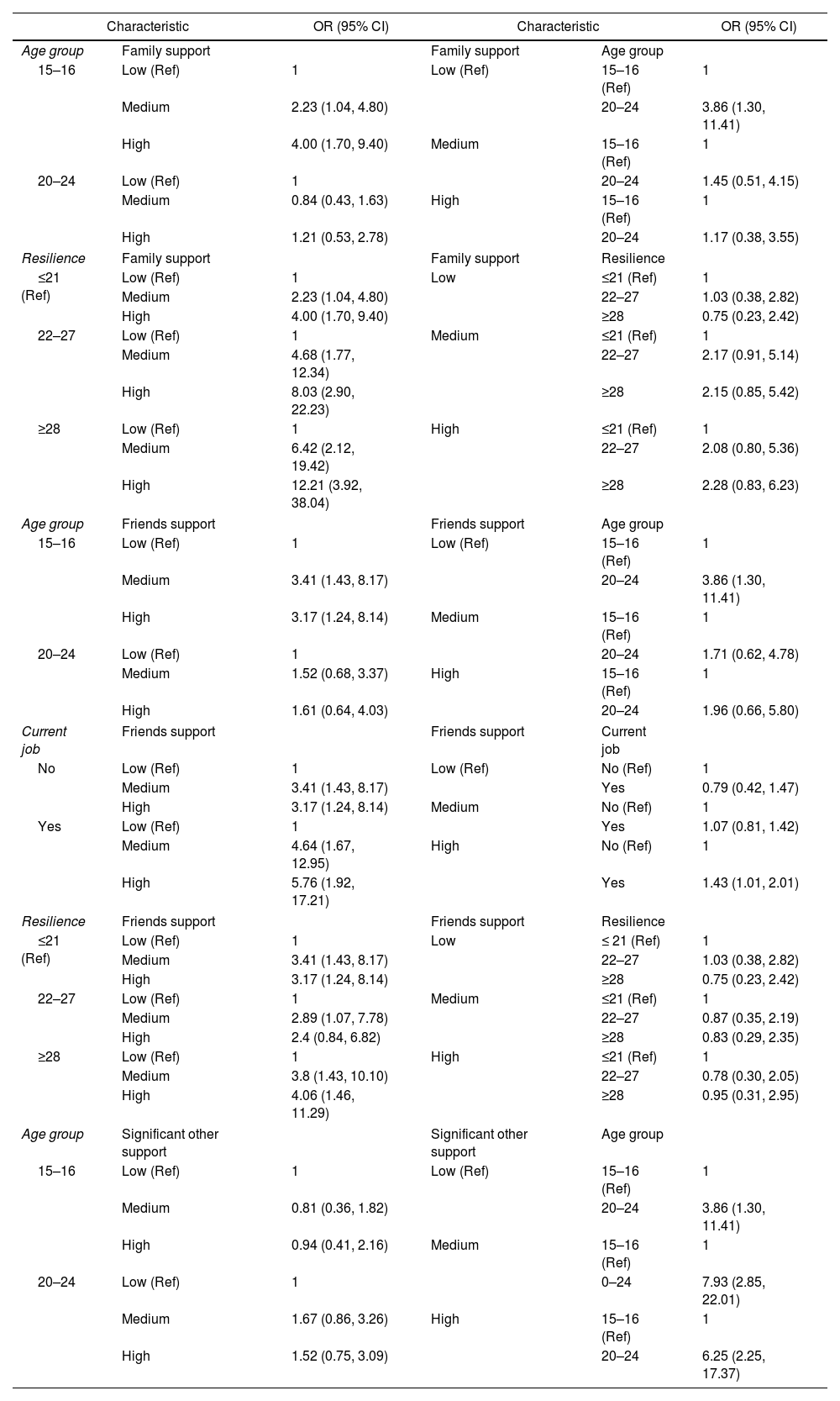

Interaction effects of perceived social support on recovery from anxiety and depression symptomsTables 4 and 5 reported results from any multivariable model where we identified statistically significant interaction effects between perceived social support and a third variable on the odds of recovery from anxiety and depression symptoms. In Table 4, we found evidence that higher social support was associated with a higher odds of recovery from depression or anxiety symptoms in: participants aged 15–16 years old compared with participants aged 20–24 years old; those currently employed, and; those who reported high levels of resilience (≥28). For example, participants with high total support and high resilience had an OR of 2.66 (95% CI: 1.73–4.10) compared with those with low support and low resilience.

Multivariable analysis (including statistically significant interactions) examining the association between the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (complete scale) and recovery from anxiety and depression symptoms.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | Total support | Total support | Age group | ||

| 15–16 | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low (Ref) | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 3.07 (0.92, 10.23) | 20–24 | 2.51 (0.93, 6.73) | ||

| High | 5.67 (1.64, 19.63) | Medium | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 | |

| 20–24 | Low (Ref) | 1 | 20–24 | 1.40 (1.02, 1.92) | |

| Medium | 1.71 (0.67, 4.36) | High | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 | |

| High | 2.55 (0.95, 6.82) | 20–24 | 1.13 (0.81, 1.56) | ||

| Current job | Total support | Total support | Current job | ||

| No | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low (Ref) | No (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 3.07 (0.92, 10.23) | Yes | 0.77 (0.34, 1.75) | ||

| High | 5.67 (1.64, 19.63) | Medium | No (Ref) | 1 | |

| Yes | Low (Ref) | 1 | Yes | 1.04 (0.77, 1.40) | |

| Medium | 4.14 (1.16, 14.74) | High | No (Ref) | 1 | |

| High | 9.49 (2.56, 35.15) | Yes | 1.29 (0.95, 1.75) | ||

| Resilience | Total support | Total support | Resilience | ||

| ≤21 (Ref) | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low | ≤21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 3.07 (0.92, 10.23) | 22–27 | 1.73 (0.56, 5.31) | ||

| High | 5.67 (1.64, 19.63) | ≥28 | 0.91 (0.20, 4.16) | ||

| 22–27 | Low (Ref) | 1 | Medium | ≤21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 3.11 (0.73, 13.24) | 22–27 | 1.75 (1.23, 2.49) | ||

| High | 4.98 (1.14, 21.74) | ≥28 | 2.25 (1.46, 3.47) | ||

| ≥28 | Low (Ref) | 1 | High | ≤21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 7.62 (1.56, 37.06) | 22–27 | 1.52 (0.97, 2.37) | ||

| High | 16.63 (3.36, 82.2) | ≥28 | 2.66 (1.73, 4.10) | ||

OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval. Model adjusted for: Age (Baseline measurement), Mental problems (Ever) (Baseline measurement), GAD-7 – Severe symptoms (Baseline measurement), PHQ-8 – Severe symptoms (Baseline measurement), Marital status, Current job, Resilience, Engagement in sports activities over the past 30 days, Engagement in arts activities over the past 30 days, Life events in the last few years, Social media score. Total number of participants: 1266, total observations: 2219.

Multivariable analysis (including significant interactions) examining the association between the three dimensions of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) and recovery from anxiety and depression symptoms.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | Family support | Family support | Age group | ||

| 15–16 | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low (Ref) | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 2.23 (1.04, 4.80) | 20–24 | 3.86 (1.30, 11.41) | ||

| High | 4.00 (1.70, 9.40) | Medium | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 | |

| 20–24 | Low (Ref) | 1 | 20–24 | 1.45 (0.51, 4.15) | |

| Medium | 0.84 (0.43, 1.63) | High | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 | |

| High | 1.21 (0.53, 2.78) | 20–24 | 1.17 (0.38, 3.55) | ||

| Resilience | Family support | Family support | Resilience | ||

| ≤21 (Ref) | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low | ≤21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 2.23 (1.04, 4.80) | 22–27 | 1.03 (0.38, 2.82) | ||

| High | 4.00 (1.70, 9.40) | ≥28 | 0.75 (0.23, 2.42) | ||

| 22–27 | Low (Ref) | 1 | Medium | ≤21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 4.68 (1.77, 12.34) | 22–27 | 2.17 (0.91, 5.14) | ||

| High | 8.03 (2.90, 22.23) | ≥28 | 2.15 (0.85, 5.42) | ||

| ≥28 | Low (Ref) | 1 | High | ≤21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 6.42 (2.12, 19.42) | 22–27 | 2.08 (0.80, 5.36) | ||

| High | 12.21 (3.92, 38.04) | ≥28 | 2.28 (0.83, 6.23) | ||

| Age group | Friends support | Friends support | Age group | ||

| 15–16 | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low (Ref) | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 3.41 (1.43, 8.17) | 20–24 | 3.86 (1.30, 11.41) | ||

| High | 3.17 (1.24, 8.14) | Medium | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 | |

| 20–24 | Low (Ref) | 1 | 20–24 | 1.71 (0.62, 4.78) | |

| Medium | 1.52 (0.68, 3.37) | High | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 | |

| High | 1.61 (0.64, 4.03) | 20–24 | 1.96 (0.66, 5.80) | ||

| Current job | Friends support | Friends support | Current job | ||

| No | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low (Ref) | No (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 3.41 (1.43, 8.17) | Yes | 0.79 (0.42, 1.47) | ||

| High | 3.17 (1.24, 8.14) | Medium | No (Ref) | 1 | |

| Yes | Low (Ref) | 1 | Yes | 1.07 (0.81, 1.42) | |

| Medium | 4.64 (1.67, 12.95) | High | No (Ref) | 1 | |

| High | 5.76 (1.92, 17.21) | Yes | 1.43 (1.01, 2.01) | ||

| Resilience | Friends support | Friends support | Resilience | ||

| ≤21 (Ref) | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low | ≤ 21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 3.41 (1.43, 8.17) | 22–27 | 1.03 (0.38, 2.82) | ||

| High | 3.17 (1.24, 8.14) | ≥28 | 0.75 (0.23, 2.42) | ||

| 22–27 | Low (Ref) | 1 | Medium | ≤21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 2.89 (1.07, 7.78) | 22–27 | 0.87 (0.35, 2.19) | ||

| High | 2.4 (0.84, 6.82) | ≥28 | 0.83 (0.29, 2.35) | ||

| ≥28 | Low (Ref) | 1 | High | ≤21 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 3.8 (1.43, 10.10) | 22–27 | 0.78 (0.30, 2.05) | ||

| High | 4.06 (1.46, 11.29) | ≥28 | 0.95 (0.31, 2.95) | ||

| Age group | Significant other support | Significant other support | Age group | ||

| 15–16 | Low (Ref) | 1 | Low (Ref) | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 |

| Medium | 0.81 (0.36, 1.82) | 20–24 | 3.86 (1.30, 11.41) | ||

| High | 0.94 (0.41, 2.16) | Medium | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 | |

| 20–24 | Low (Ref) | 1 | 0–24 | 7.93 (2.85, 22.01) | |

| Medium | 1.67 (0.86, 3.26) | High | 15–16 (Ref) | 1 | |

| High | 1.52 (0.75, 3.09) | 20–24 | 6.25 (2.25, 17.37) | ||

Table 5 reported any such statistically significant interactions for each of the three dimensions of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support—family, friends, and significant other support. Results highlighted that support from family, friends, and significant others interacted with age to influence the odds of recovery. Support from family and friends was associated with stronger odds of recovery in the younger age group (15–16 years old) than the older age group (20–24 years old), while support from a significant other was only associated with increased odds of recovery in the older age group. As for total perceived social support, the greatest odds of recovery were found for those with both higher levels of support from family and friends and higher levels of self-reported resilience; no such trend was observed for support from a significant other. The odds of recovery associated with higher perceived social support from friends were higher for those in employment compared with those who were unemployed. Non-significant interactions are presented in Annexes 1 and 2.

DiscussionOur cohort study in deprived areas of three major South American cities found that adolescents and young adults with clinically relevant symptoms of depression and/or anxiety at baseline had greater odds of symptomatic recovery at 12- and 24-month follow-ups if they reported medium to high levels of perceived social support, especially from family and friends.

In this study, we found that support from family and friends were stronger predictors of symptomatic recovery during follow-up than support from a significant other. Given the young age of our sample, these findings have some face validity, with family support identified as a stronger predictor than support from friends, while young people may not have had sufficient time to develop strong support from a significant other. Nonetheless, this finding needs to be interpreted with caution. The term ‘significant other’ is not commonly used in Latin American countries, so some participants may have misunderstood the term. For young adults and adolescents, it might be difficult to differentiate significant other from friends and family. In fact, Latin American Spanish, lacks a direct and widely recognized equivalent for the term. Instead, more culturally familiar terms such as “pareja” (partner), “novio/a” (boyfriend/girlfriend), or “esposo/a” (husband/wife) are more commonly used to refer to romantic partners. As a result, responses to this item may have varied depending on each participant's interpretation of the term, potentially introducing measurement bias. Future studies involving Spanish-speaking populations should consider using culturally and linguistically appropriate terms to ensure clarity—particularly when assessing sources of social support among adolescents and young adults. Using clearer, more familiar terms may enhance the accuracy and interpretability of responses in this context.

Interestingly, the whole sample had relatively high perceived social support at baseline, and this was sustained throughout the 2-year follow-up period. A possible explanation is that in deprived areas of these Latin American cities, the most readily available resource is social relationships which could explain the sustained high perceived social support.34,35

The association between perceived social support and low recovery rates could be bidirectional, for example, depression may cause decreased self-esteem and/or less social interactions, which could subsequently lead to lower perceived social support. Conversely, high perceived social support may lead to higher self-esteem and may reflect their actual reality: family and interpersonal resources that help individuals deal with stress and improve wellbeing. It is also important to consider the possibility of reverse causality: individuals who experience clinical improvement over time may also begin to perceive greater support from others, either because they are more socially engaged or because their improved mood affect how they interpret their social environment.

Additionally, interaction analyses revealed that higher social support is associated with better recovery, particularly among those who are employed, possibly due to the social networks provided by the workplace. In contrast, this effect is smaller among the unemployed, who may have fewer opportunities for social interaction. Similarly, support from a significant other appears to influence recovery primarily in older individuals, for whom such relationships may play a more central role. Nonetheless, because our study assessed perceived social support at baseline and followed participants over time, its longitudinal design strengthens the interpretation that social support may influence recovery. However, the possibility of reverse causality—where recovery itself leads to higher perceived social support—cannot be entirely ruled out.

Finally, the persistence of depressive and anxiety symptoms despite good perceived social support raises important questions. As participants were selected from deprived neighborhoods in urban areas, socioeconomic factors may partially explain the low recovery rate. Even though perceived social support has a positive impact for adolescents and young adults, the difficulties and adversities that arise from living adverse social conditions could account for the persistent mental health problems. In particular, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic compounded with social turmoil and economic uncertainty for the younger generation in the three countries could explain the limited protective effect of perceived social support, which asks for the immediate or proximal relationships and not for the broader social context.36 However, the high social support is a positive element in the life of the persons.

Comparison with other resultsThere are few studies in adolescents and young adults in Latin America looking at psychological distress and perceived social support. Some studies have looked at immigrant Latin population and first-generation Latinos in the US. For example, Almeida and colleagues found that higher levels of family support, and not friends, was correlated with lower levels of depression.37 In an adolescent rural population, Weber and colleagues found a negative correlation between peer social support, family support and depressive symptoms.38 In another study in China with university students during the COVID-19 pandemic, Shu and colleagues found that social support decreased symptoms of anxiety.39 Bruwer and colleagues found that higher scores in perceived social support had a negative correlation with depression, childhood trauma and experience of trauma.40

In summary, most studies have shown that higher perceived social support is a protective factor for mental health, but only a few in comparable populations.

StrengthsThis is a cohort study with a large sample and longer follow-up than what is in the current literature, with low dropout rate (30%). In addition, participants came from vulnerable urban populations in two different age groups and from 3 different major cities of Latin America, and understudied population.

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. First, as this is an observational study causation cannot be established, only correlations. Second, although the analysis controlled for well-established variables related to depression and anxiety symptoms, we cannot exclude other confounders missing in the measurements used. Additionally, the sample size was not designed to assess interactions, resulting in wide and imprecise confidence intervals. Therefore, results should be interpreted with caution. Third, the sample was selected purposively and is not necessarily representative of the population in each city. Fifth, cultural and linguistic challenges related to the term significant other limits the interpretation of the domains separately. Finally, the study experienced loss to follow-up—12.7% at 12 months and an additional 29.5% between 12 and 24 months—yielding a cumulative retention rate of 70.5%. This may introduce selection bias if those lost to follow-up differ systematically from those retained, particularly in characteristics related to the outcomes of interest. To explore this possibility, we included in the supplementary material a descriptive table comparing baseline characteristics between followed and non-followed participants at both time points, providing context for the interpretation of our findings (Annex 4).

Future directionsA public health approach should recognize social support as a key component in improving mental health in young people. The importance of having high perceived social support for young adults and adolescents in increasing the probability of recovery from depressive and anxiety symptoms justifies the testing and implementation of interventions that might improve perceived social support. These interventions could include a psychoeducation component, so that young adults and adolescents understand the importance of maintaining/improving social support when dealing with stressors or mental health problems. For example, a psychoeducational intervention showed improvement in perceived family support, hypothesized via increasing self-esteem and frequency of self-reinforcement.41 Another question for future research includes when in the life course to carry programs addressing perceived social support. In addition, it is important to explore how we can better understand the link between perceived social support and depression and anxiety, including when and how to target social support, as this could further improve mental health outcomes for young people in deprived areas of Latin America.

ConclusionThis longitudinal study highlights the crucial role of perceived social support, particularly from family and friends, in facilitating the recovery from depressive and anxiety symptoms among adolescents and young adults living in disadvantaged urban areas across three Latin American cities. Nevertheless, even with substantial social support, addressing broader socioeconomic and contextual factors remains essential for facilitating recovery. Future interventions should focus on improving both the availability and quality of social support while simultaneously addressing structural inequalities to improve mental health outcomes in vulnerable communities.

Non-author contributionsWe would like to thank the following researchers for their contribution to participant recruitment and data collection. All named researchers have provided written permission for their names to be acknowledged in this paper and there are no additional conflicts of interest to declare.

From Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, School of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina: Sofia Madero (BA), Fernando Esnal (BA), Santiago Cesar Lucchetti (BA).

From Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia: María Paula Jassir Acosta (MD), Ángela Flórez-Varela (PGDip), Laura Cruz Marin (BA), Sandra Milena Cañón Gonzalez (BA), María Camila Roldán Bernal (MD), Miguel Esteban Uribe (BA), Karen Ariza-Salazar (BA), who also contributed as project coordinator, and Jesus David Niño (BA) for his contributions to the data cleansing process and his input on data analysis considerations.

From CRONICAS Center of Excellence in Chronic Diseases, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Perú: Jimena Rivas (BA), Adriana Carbonel (BA), Heidy Sanchez (BA), Noelia Cusihuaman-Lope (BA), Jenny Bejarano (BA), and Liliana Hidalgo-Padilla (MA) who also contributed as project coordinator.

FundingThis work was supported by the Medical Research Council [grant number MR/S03580X/1].

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to all study participants for generously sharing their data, experiences, and perspectives.