Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in young people from urban neighbourhoods in Latin America (OLA)

Más datosAssess the association between experiencing parental alcohol misuse with depression, anxiety and frequency of alcohol use among young people, and evaluate participants’ coping strategies as effect modifiers.

MethodsParticipants were adolescents and young adults from deprived Bogotá, Buenos Aires, and Lima areas. We evaluated the relationship between experiencing parental alcohol misuse and presence of depression (PHQ-8), anxiety (GAD-7), and frequency of alcohol use (ASSIST), and examined the modifying effect of coping (CCSC-R1).

ResultsYoung people who experienced parental alcohol misuse in the last year had 2.41 and 2.30 times higher odds of having depression and anxiety, respectively, and 1.91 and 2.49 times higher odds of drinking monthly and weekly, compared to those who did not. Those who experienced it more than a year ago had 1.60 and 1.58 times higher odds of having depression and anxiety, respectively, compared to participants who did not. Coping strategies were not significant effect modifiers.

ConclusionsParental alcohol misuse is associated with emotional distress and frequency of alcohol use in young people. Family-based interventions should address youth drinking and promote positive parenting practices.

Explorar la asociación entre experimentar el uso inadecuado de alcohol en los padres, la presencia de síntomas de depresión, ansiedad y frecuencia del consumo de alcohol, y evaluar las estrategias de afrontamiento como modificadores de efecto.

MétodosLos participantes fueron adolescentes y adultos jóvenes de barrios desfavorecidos de Bogotá, Buenos Aires y Lima. Evaluamos la asociación entre experimentar el uso inadecuado de alcohol en los padres y la presencia de depresión (PHQ-8), ansiedad (GAD-7) y frecuencia del consumo de alcohol (ASSIST). Examinamos el efecto modificador del afrontamiento (CCSC-R1).

ResultadosLos jóvenes expuestos al uso inadecuado de alcohol en los padres en el último año presentaron 2,41 y 2,30 veces más probabilidades de sufrir depresión y ansiedad, respectivamente, y 1,91 y 2,49 veces más probabilidades de consumir alcohol mensualmente y semanalmente, en comparación con quienes no vivieron esta situación. Aquellos expuestos hace más de un año tuvieron 1,60 y 1,58 veces más probabilidades de depresión y ansiedad, respectivamente. Las estrategias de afrontamiento no mostraron ser modificadores significativos del efecto.

ConclusionesEl uso inadecuado de alcohol en los padres se asocia al malestar emocional y al consumo de alcohol en jóvenes. Intervenciones con enfoque familiar deben abordar el consumo de alcohol temprano y promover prácticas de crianza positivas.

Adolescence and young adulthood are critical stages for the onset of mental health disorders (MHD).1 Worldwide, it is estimated that one in seven 10–19-year-olds experience MHD, with anxiety and depression among the most common conditions.2 In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), they account for almost 50% of MHD among the same age group.3 Additionally, these MHDs have been previously associated with alcohol consumption in young adults and adolescents from LAC, where 12% of this population reported having an alcohol use disorder.4 Therefore, it is essential to identify the various factors influencing youth mental health in this context.

Exposure to adverse life events can be a strong predictor of mental health outcomes.5 Parental alcohol misuse, which refers to a range of problem drinking (i.e. binge drinking, hazardous drinking, alcohol dependency) by adults with parental responsibility,6 can have a long-term impact. Young people who experienced this event as children tend to drink more than people who did not, usually starting this behaviour earlier.7–9 While few studies have addressed outcomes different from substance use,10 it also has been noted that both adults and adolescents who experienced parental alcohol misuse reported significantly more depression and anxiety symptoms.11,12

Recently, investigations have emphasised the role of resilience factors when addressing children of people with alcohol problems.13,14 Coping is defined as intentional efforts to regulate emotions, thoughts, and behaviours in response to stressful situations.15 As this experience can be a chronic stressor, it is important to understand how people cope with the challenges associated with parental drinking.16 Young adults who experienced parental alcohol misuse have previously reported using avoidance or withdrawal coping strategies.17 However, few studies focus on coping in people who report this event.

Additionally, most research on this topic comes from high-income countries. Since societal and economic factors influence household alcohol use patterns, findings are not necessarily applicable to low- and middle-income countries.18 Therefore, this study aims to assess the association between experiencing parental alcohol misuse and depression, anxiety and alcohol consumption in young people from urban deprived areas in Bogotá, Buenos Aires and Lima, as well as to evaluate if different coping strategies are effect modifiers.

MethodsDesign and settingThis case-control study for symptoms of depression and anxiety uses data gathered between April 2021 and November 2022 as part of a larger research programme: “Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in young people from urban areas in Latin America (OLA)”. The programme aimed to identify the resources that help young people from Bogotá (Colombia), Buenos Aires (Argentina) and Lima (Peru) prevent or recover from depression and/or anxiety.19

ParticipantsParticipants were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: a) being 15–16 (adolescents) or 20–24 years old (young adults); b) living in the city's 50% most deprived areas, and c) having the ability to give informed consent or assent. In the case of adolescents, informed consent from a parent or tutor was required. Exclusion criteria included: (a) severe mental illness (i.e. psychosis), (b) cognitive impairment and (c) illiteracy.

Researchers aimed to recruit 2040 participants across the three cities, including 1020 (340 in each site) who met the criteria for symptoms of depression and/or anxiety (PHQ-8 and/or GAD-7 score≥10). The sampling method was non-randomised. The recruitment used convenience sampling, and the strategies varied across the three cities, considering COVID-19 restrictions and regulations. Additional details of the study sample and recruitment processes are described in previous publications.19,20

ProceduresOnce the inclusion criteria were verified and the informed assent and/or consent collected, participants completed a paper or online questionnaire. The assessments usually took 30–60min and were done individually or in groups under the supervision of a trained research assistant. The survey data was recorded using REDCap, a data collection software.21 Regarding paper questionnaires, data was manually entered by a trained researcher.

Variables and instrumentsDependent variablesTo address depression symptoms, we used the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8),22 an 8-item questionnaire that assesses symptoms of depression in the last two weeks. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 (no days) to 3 (almost every day), with the total score ranging from 0 to 24.

We assessed anxiety symptoms using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7),23 a 7-item questionnaire that assesses symptoms of anxiety in the last two weeks. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 (no days) to 3 (almost every day), with the total score ranging from 0 to 21.

We used a cut-off score of ≥10 to indicate moderate to severe symptoms of both depression and anxiety, as it demonstrates adequate sensitivity and specificity for detecting symptoms.24,25 It was also used to categorise participants into cases and controls, i.e. those with and without symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. Additionally, both of the instruments have been validated in Latin American settings.26–29

To assess the frequency of alcohol consumption in the last three months, we used a question from the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST)30 (“In the past three months, how often have you used alcoholic beverages?”). The original variable included five response options, but for the analysis, these were grouped into three categories: (1) not used in the previous three months, (2) used monthly or less, and (3) used weekly, daily, or almost daily. This information was only obtained from participants who reported having consumed alcohol “at least once in their lifetime”.

Independent variablesTo identify if a participant experienced parental alcohol misuse, we used an item from the adaptation of the Adolescent Appropriate Life Events Scale31 (“Your parents/caregivers/partner drank alcohol so frequently that it caused family problems”). The variable had four levels: (1) never experienced it, (2) experienced it more than a year ago, (3) experienced it in the last year, and (4) experienced it more than a year ago and the last year. For the analysis, levels 3 and 4 were collapsed into a single group due to the low frequency of responses in level 4.

We could not run the analysis with participants who reported experiencing parental alcohol misuse in the last year and more than a year ago because the sample was too small. Rather than excluding these participants, we grouped them with those who reported experiencing the event in the last year. Thus, we had three groups of participants: those who never experienced parental alcohol misuse, those who did more than a year ago, and those who did in the last year.

Effect modifierCoping Strategies were addressed using the shortened version of the Children's Coping Strategies Checklist (CCSC-R1),32 a 25-item questionnaire that assesses the frequency of using coping strategies. Each is scored on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (most of the time) and divided into four dimensions: active coping, distraction strategies, avoidance strategies, and support-seeking strategies. Each comprised eleven, four, six, and four items, respectively. We used the continuous score of each dimension and analysed them separately. Higher scores indicated increased use of the strategy.

Confounding variablesWe selected the following variables: gender (male, female, other), age group (adolescent, young adult), main occupation (work, study, housewife, no occupation), and household crowding (categorised based on the number of people per bedroom: ≤2 per bedroom, >2 per bedroom).

Data analysisWe used STATA 18.033 for all descriptive and inferential analyses. After excluding those with missing values, all participants with complete data for all the variables of interest were included.

We calculated the frequency of depressive and anxiety symptoms and the frequency of each category of alcohol use by the different sociodemographic groups. Regarding continuous variables, medians and interquartile ranges are reported. Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to explore the differences between the continuous variables and the outcomes.

Binomial logistic regressions were used for the outcomes of symptoms of depression and anxiety, and multinomial logistic regressions for participants’ frequency of alcohol use. We performed crude and adjusted logistic regressions. All the adjusted models included the same sociodemographic variables (i.e. gender, age group, main occupation and household crowding) and coping strategies. Additionally, an interaction term was added to the models to see if coping strategies modified the effect of problematic parental use on the outcomes. Then, a Likelihood Ratio test was used to compare the models with and without the interaction term.

Ethics considerationsThe OLA programme received approval from the Ethics Committees of Queen Mary University of London (QMERC2020/02), Universidad de Buenos Aires, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (FM-CIE-1138-20) and Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (Constancia 581-33-20). Informed consent procedures were carried out in the three cities. In the case of participants under 18 years old, a parent or tutor provided informed consent alongside assent from the young person. Each participant was assigned an ID number to ensure anonymity, and any identifiable information was kept secure. Researchers put risk management protocols in place to ensure the well-being of participants with high scores of depression or anxiety.

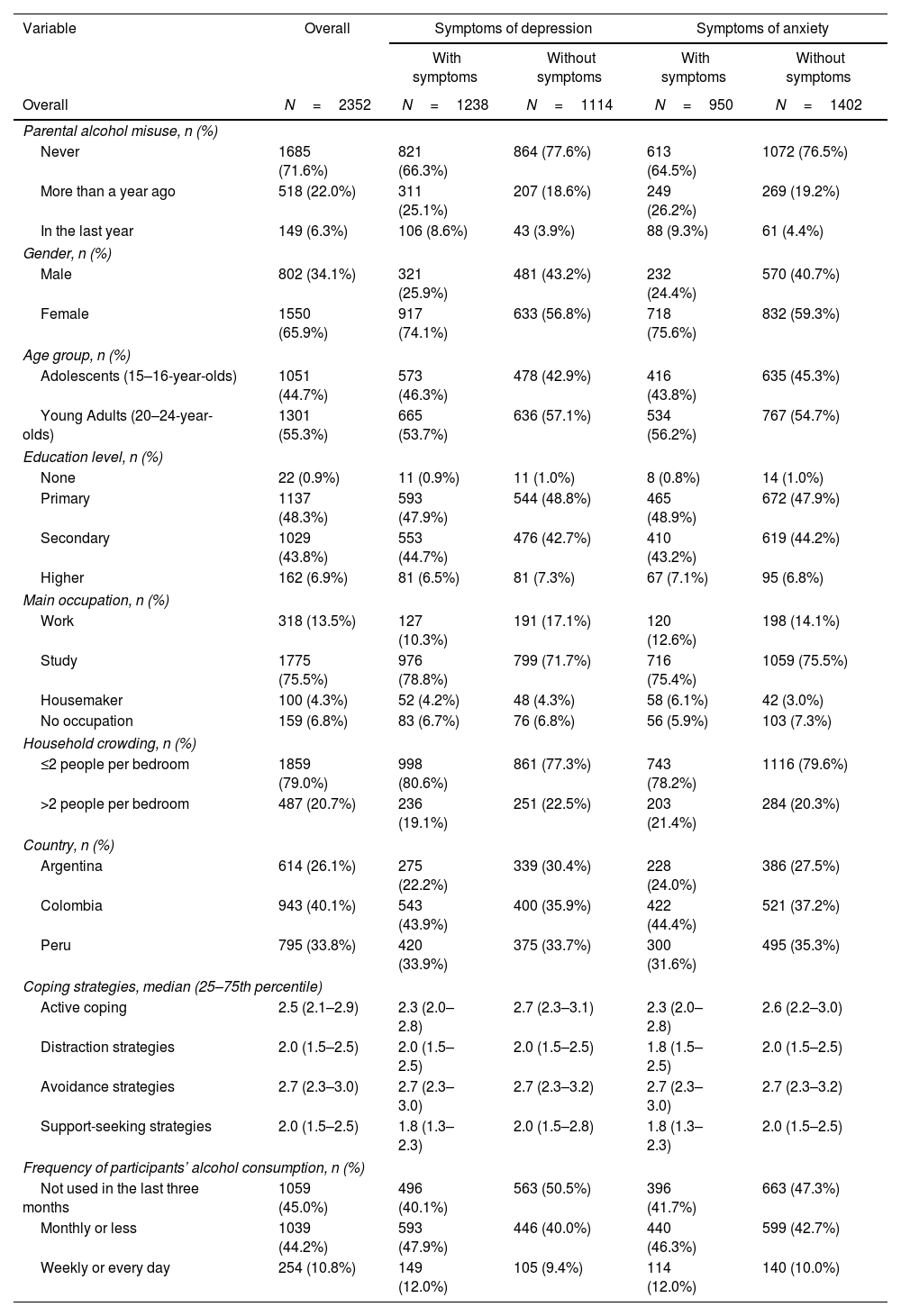

ResultsThe study sample included 2402 participants. However, 50 participants had missing values in at least one of the used variables, so we only analysed information from 2352 participants. In our sample, 22.0% had reported experiencing parental alcohol misuse more than a year ago, and 6.3% experienced the event in the last year. Additionally, 52.6% had symptoms of depression, and 40.4% had symptoms of anxiety. Other details include that 65.9% were women, 55.3% were young adults, and 75.5% were students.

The proportion of symptoms of depression and anxiety by the participants’ characteristics is shown in Table 1. The proportion of young people with symptoms of depression was higher among those who experienced parental alcohol misuse in the last year, identified as female and had lower scores of active coping and support-seeking strategies. In the case of young people with symptoms of anxiety, the proportion of participants was higher among those who experienced the event in the last year, identified as female, and had lower scores of active coping and support-seeking strategies.

Sociodemographic characteristics by symptoms of depression and anxiety.

| Variable | Overall | Symptoms of depression | Symptoms of anxiety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With symptoms | Without symptoms | With symptoms | Without symptoms | ||

| Overall | N=2352 | N=1238 | N=1114 | N=950 | N=1402 |

| Parental alcohol misuse, n (%) | |||||

| Never | 1685 (71.6%) | 821 (66.3%) | 864 (77.6%) | 613 (64.5%) | 1072 (76.5%) |

| More than a year ago | 518 (22.0%) | 311 (25.1%) | 207 (18.6%) | 249 (26.2%) | 269 (19.2%) |

| In the last year | 149 (6.3%) | 106 (8.6%) | 43 (3.9%) | 88 (9.3%) | 61 (4.4%) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 802 (34.1%) | 321 (25.9%) | 481 (43.2%) | 232 (24.4%) | 570 (40.7%) |

| Female | 1550 (65.9%) | 917 (74.1%) | 633 (56.8%) | 718 (75.6%) | 832 (59.3%) |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||

| Adolescents (15–16-year-olds) | 1051 (44.7%) | 573 (46.3%) | 478 (42.9%) | 416 (43.8%) | 635 (45.3%) |

| Young Adults (20–24-year-olds) | 1301 (55.3%) | 665 (53.7%) | 636 (57.1%) | 534 (56.2%) | 767 (54.7%) |

| Education level, n (%) | |||||

| None | 22 (0.9%) | 11 (0.9%) | 11 (1.0%) | 8 (0.8%) | 14 (1.0%) |

| Primary | 1137 (48.3%) | 593 (47.9%) | 544 (48.8%) | 465 (48.9%) | 672 (47.9%) |

| Secondary | 1029 (43.8%) | 553 (44.7%) | 476 (42.7%) | 410 (43.2%) | 619 (44.2%) |

| Higher | 162 (6.9%) | 81 (6.5%) | 81 (7.3%) | 67 (7.1%) | 95 (6.8%) |

| Main occupation, n (%) | |||||

| Work | 318 (13.5%) | 127 (10.3%) | 191 (17.1%) | 120 (12.6%) | 198 (14.1%) |

| Study | 1775 (75.5%) | 976 (78.8%) | 799 (71.7%) | 716 (75.4%) | 1059 (75.5%) |

| Housemaker | 100 (4.3%) | 52 (4.2%) | 48 (4.3%) | 58 (6.1%) | 42 (3.0%) |

| No occupation | 159 (6.8%) | 83 (6.7%) | 76 (6.8%) | 56 (5.9%) | 103 (7.3%) |

| Household crowding, n (%) | |||||

| ≤2 people per bedroom | 1859 (79.0%) | 998 (80.6%) | 861 (77.3%) | 743 (78.2%) | 1116 (79.6%) |

| >2 people per bedroom | 487 (20.7%) | 236 (19.1%) | 251 (22.5%) | 203 (21.4%) | 284 (20.3%) |

| Country, n (%) | |||||

| Argentina | 614 (26.1%) | 275 (22.2%) | 339 (30.4%) | 228 (24.0%) | 386 (27.5%) |

| Colombia | 943 (40.1%) | 543 (43.9%) | 400 (35.9%) | 422 (44.4%) | 521 (37.2%) |

| Peru | 795 (33.8%) | 420 (33.9%) | 375 (33.7%) | 300 (31.6%) | 495 (35.3%) |

| Coping strategies, median (25–75th percentile) | |||||

| Active coping | 2.5 (2.1–2.9) | 2.3 (2.0–2.8) | 2.7 (2.3–3.1) | 2.3 (2.0–2.8) | 2.6 (2.2–3.0) |

| Distraction strategies | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 1.8 (1.5–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) |

| Avoidance strategies | 2.7 (2.3–3.0) | 2.7 (2.3–3.0) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 2.7 (2.3–3.0) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) |

| Support-seeking strategies | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) | 2.0 (1.5–2.8) | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) |

| Frequency of participants’ alcohol consumption, n (%) | |||||

| Not used in the last three months | 1059 (45.0%) | 496 (40.1%) | 563 (50.5%) | 396 (41.7%) | 663 (47.3%) |

| Monthly or less | 1039 (44.2%) | 593 (47.9%) | 446 (40.0%) | 440 (46.3%) | 599 (42.7%) |

| Weekly or every day | 254 (10.8%) | 149 (12.0%) | 105 (9.4%) | 114 (12.0%) | 140 (10.0%) |

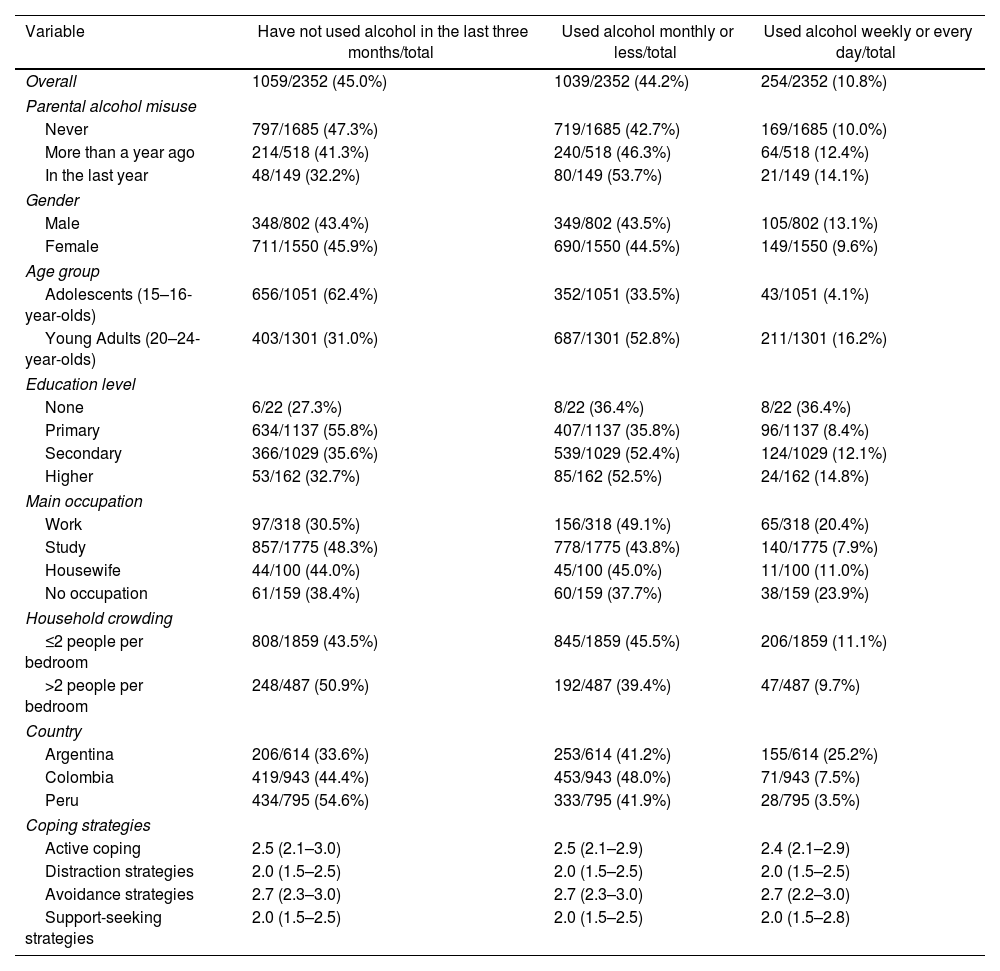

Table 2 shows the proportion of alcohol use in the last three months by the participants’ characteristics. The proportion of participants who used alcohol weekly or daily was higher among those who experienced parental alcohol misuse in the last year, identified as male, and reported no occupation. In the case of participants who drank monthly or less, the proportion was higher among those who reported the event in the last year, identified as female, and worked as their main occupation. Finally, the proportion of participants who had not used alcohol in the last three months was higher among those who had never experienced the event, identified as females, and were students.

Sociodemographic characteristics by participants’ alcohol use in the last three months.

| Variable | Have not used alcohol in the last three months/total | Used alcohol monthly or less/total | Used alcohol weekly or every day/total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1059/2352 (45.0%) | 1039/2352 (44.2%) | 254/2352 (10.8%) |

| Parental alcohol misuse | |||

| Never | 797/1685 (47.3%) | 719/1685 (42.7%) | 169/1685 (10.0%) |

| More than a year ago | 214/518 (41.3%) | 240/518 (46.3%) | 64/518 (12.4%) |

| In the last year | 48/149 (32.2%) | 80/149 (53.7%) | 21/149 (14.1%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 348/802 (43.4%) | 349/802 (43.5%) | 105/802 (13.1%) |

| Female | 711/1550 (45.9%) | 690/1550 (44.5%) | 149/1550 (9.6%) |

| Age group | |||

| Adolescents (15–16-year-olds) | 656/1051 (62.4%) | 352/1051 (33.5%) | 43/1051 (4.1%) |

| Young Adults (20–24-year-olds) | 403/1301 (31.0%) | 687/1301 (52.8%) | 211/1301 (16.2%) |

| Education level | |||

| None | 6/22 (27.3%) | 8/22 (36.4%) | 8/22 (36.4%) |

| Primary | 634/1137 (55.8%) | 407/1137 (35.8%) | 96/1137 (8.4%) |

| Secondary | 366/1029 (35.6%) | 539/1029 (52.4%) | 124/1029 (12.1%) |

| Higher | 53/162 (32.7%) | 85/162 (52.5%) | 24/162 (14.8%) |

| Main occupation | |||

| Work | 97/318 (30.5%) | 156/318 (49.1%) | 65/318 (20.4%) |

| Study | 857/1775 (48.3%) | 778/1775 (43.8%) | 140/1775 (7.9%) |

| Housewife | 44/100 (44.0%) | 45/100 (45.0%) | 11/100 (11.0%) |

| No occupation | 61/159 (38.4%) | 60/159 (37.7%) | 38/159 (23.9%) |

| Household crowding | |||

| ≤2 people per bedroom | 808/1859 (43.5%) | 845/1859 (45.5%) | 206/1859 (11.1%) |

| >2 people per bedroom | 248/487 (50.9%) | 192/487 (39.4%) | 47/487 (9.7%) |

| Country | |||

| Argentina | 206/614 (33.6%) | 253/614 (41.2%) | 155/614 (25.2%) |

| Colombia | 419/943 (44.4%) | 453/943 (48.0%) | 71/943 (7.5%) |

| Peru | 434/795 (54.6%) | 333/795 (41.9%) | 28/795 (3.5%) |

| Coping strategies | |||

| Active coping | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) | 2.5 (2.1–2.9) | 2.4 (2.1–2.9) |

| Distraction strategies | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) |

| Avoidance strategies | 2.7 (2.3–3.0) | 2.7 (2.3–3.0) | 2.7 (2.2–3.0) |

| Support-seeking strategies | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.8) |

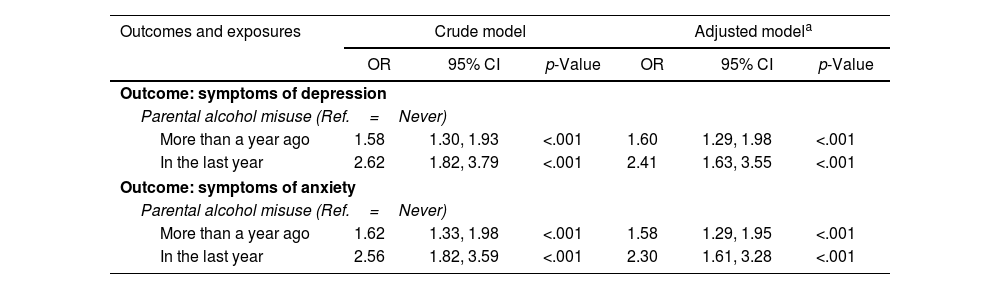

The logistic regressions reveal a significant association between experiencing parental alcohol misuse and having symptoms of depression and anxiety, these associations being more pronounced when the event took place in the last year (Table 3). The adjusted model shows that participants who experienced this event in the last year had 2.41 times higher odds of having symptoms of depression (95% CI=1.63–3.55, p<.001) than the ones who did not experience the event. In comparison, those who experienced it more than a year ago had 1.60 times higher odds of developing depression symptoms (95% CI=1.29–1.98, p<.001) compared to those who did not experience it.

Crude and adjusted logistic regressions for the association between problematic parental alcohol use and depression and anxiety symptoms.

| Outcomes and exposures | Crude model | Adjusted modela | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Outcome: symptoms of depression | ||||||

| Parental alcohol misuse (Ref.=Never) | ||||||

| More than a year ago | 1.58 | 1.30, 1.93 | <.001 | 1.60 | 1.29, 1.98 | <.001 |

| In the last year | 2.62 | 1.82, 3.79 | <.001 | 2.41 | 1.63, 3.55 | <.001 |

| Outcome: symptoms of anxiety | ||||||

| Parental alcohol misuse (Ref.=Never) | ||||||

| More than a year ago | 1.62 | 1.33, 1.98 | <.001 | 1.58 | 1.29, 1.95 | <.001 |

| In the last year | 2.56 | 1.82, 3.59 | <.001 | 2.30 | 1.61, 3.28 | <.001 |

OR=odds ratio.

95% CI=95% confidence interval.

Similarly, in the adjusted model, participants who experienced parental alcohol misuse in the last year had 2.30 times higher odds of developing symptoms of anxiety (95% CI=1.61–3.28, p<.001) than the ones who never faced this event. In the case of young people who experienced the event more than a year ago, they had 1.58 times higher odds of developing anxiety symptoms (95% CI=1.29–1.95, p<.001) than those who never experienced it.

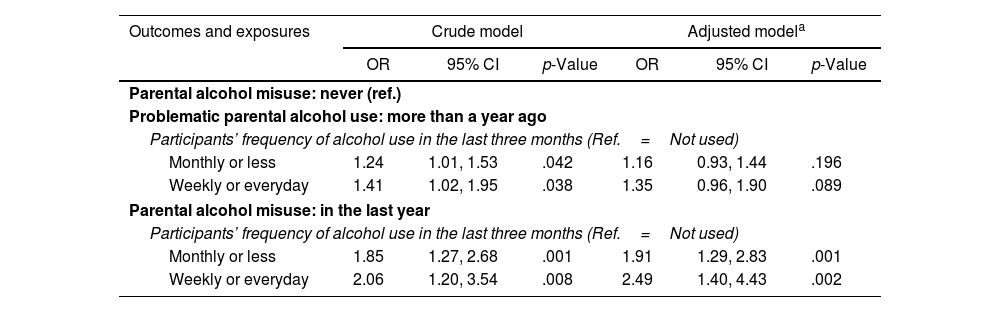

Additionally, the adjusted estimates from the multinomial logistic regressions showed that experiencing parental alcohol misuse was associated with the frequency of the participants’ alcohol consumption over the last three months (Table 4). This association was only significant if the stressful event occurred in the last year, and not if it happened more than a year ago. Thus, the adjusted model revealed that participants who reported parental alcohol misuse in the last year had 1.91 times higher odds of drinking monthly or less (95% CI=1.29–2.83, p=.001) than those who did not report the event. Moreover, participants had 2.49 times higher odds of using alcohol weekly or every day in the last three months if they had experienced the event in the last year (95% CI=1.40–4.43, p=.002) than the ones who did not experience the event.

Crude and adjusted multinomial logistic regressions for the association between problematic parental alcohol use and participants’ frequency of alcohol use.

| Outcomes and exposures | Crude model | Adjusted modela | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Parental alcohol misuse: never (ref.) | ||||||

| Problematic parental alcohol use: more than a year ago | ||||||

| Participants’ frequency of alcohol use in the last three months (Ref.=Not used) | ||||||

| Monthly or less | 1.24 | 1.01, 1.53 | .042 | 1.16 | 0.93, 1.44 | .196 |

| Weekly or everyday | 1.41 | 1.02, 1.95 | .038 | 1.35 | 0.96, 1.90 | .089 |

| Parental alcohol misuse: in the last year | ||||||

| Participants’ frequency of alcohol use in the last three months (Ref.=Not used) | ||||||

| Monthly or less | 1.85 | 1.27, 2.68 | .001 | 1.91 | 1.29, 2.83 | .001 |

| Weekly or everyday | 2.06 | 1.20, 3.54 | .008 | 2.49 | 1.40, 4.43 | .002 |

OR=odds ratio.

95% CI=95% confidence interval.

Furthermore, we evaluated if the frequency of use of different coping strategies was an effect modifier in the relationship between parental alcohol misuse and mental health outcomes, as well as the frequency of alcohol use. Neither active, distractive, avoidance nor support-seeking strategies were significant effect modifiers (Supplementary Material).

DiscussionOur results show that for young people, experiencing parental alcohol misuse in the last year or more than a year ago significantly increased the odds of having symptoms of both depression and anxiety, which is consistent with previous findings.11–13 Growing up with a parent with alcohol problems has the potential to cause emotional harm, as the parent-child interactions differ from typical dynamics.34 People who experienced this event report anxiety and stress from unpredictable and inconsistent parenting,35,36 as well as feelings of shame, anger, guilt and fear of stigma for coming from families who misuse alcohol.37,38

Although the event's impact was stronger when experienced in the last year, it still raised the odds of symptoms if it occurred over a year ago. While recent adverse life events can have a greater impact than distant ones,5,39 it is suggested that experiences involving interpersonal problems (i.e. ongoing conflict with someone close to you) can be particularly impactful.40 As parental alcohol misuse represents a significant stressor in the family setting and potentially results in a strained parent-child relationship,41,42 the event's impact may remain significant irrespective of when it occurred.

Regarding the event's impact on alcohol consumption, participants who experienced it in the last year drank more frequently than those who did not, aligning with previous research.9 This behaviour usually occurs both during young adulthood8,43 and adolescence.7,18 This event impacts overall family functioning and parenting practices, which are critical to understanding how young people use alcohol.44–46

For example, parents with alcohol issues usually are more permissive towards drinking, which is often a predictor for later alcohol misuse.14,47 Studies in Peru and Argentina found that parental monitoring helped prevent substance use outcomes.48,49 It is important to consider the cultural and societal factors around alcohol consumption in Latin American contexts, as most adolescents drink for the first time before the age of 14 and usually obtain alcohol from family members.50

Similar to previous research,51,52 participants with symptoms of depression and anxiety had lower scores of active coping and support-seeking strategies. Only distraction strategies, which involve engaging in other activities to avoid dealing with or thinking about the current problem,53 showed a significant association with alcohol use in this study. Very few studies focus on the coping strategies used by this particular population, and they tend to report the use of more avoidant strategies.16,17 However, these may overlap depending on the categorisation of the strategies, sometimes distraction being included in avoidance.54

Finally, while different coping strategies may have an effect on mental health outcomes and the frequency of the participants’ alcohol consumption, in our study they do not significantly modify the impact of problematic parental alcohol use. Previous research has shown mixed results; for example, a study in the US with adult children of people with alcohol-related issues found that, regardless of which coping strategy they used, alcohol consumption and depression did not differ from their counterparts.16 However, others reported coping strategies can have a mediating role between the event and the same outcomes.55 In general, people who experienced parental alcohol misuse tend to develop fewer and less effective strategies in comparison to their peers,11,56 so it is crucial to further explore the role of coping in this group.

ImplicationsThis study highlights how experiencing parental alcohol misuse can significantly impact youth's mental health and alcohol consumption, specifically in deprived urban areas in Latin America. This is relevant since this issue is not usually studied in low-income countries, and previous research has found that young people with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to report parental drinking.57,58

Efforts should be made to design awareness campaigns and preventive interventions about youth and adolescent drinking. Family-based intervention programmes may be useful, as previous interventions have been effective in reducing the prevalence of alcohol misuse or influencing drinking behaviours while focusing on parenting factors.59–61 These could also benefit from partnering with young people with lived experience of the event from its inception.

Notably, coping strategies did not have a moderating role in our sample. Future research could focus on other protective mental health factors, as it is an understudied area in this population.62 For example, sense of belonging and parental attachment have previously been identified as mediators between parental alcoholism and mental health outcomes.63,64 This knowledge could also help policymakers make informed decisions about further actions or enhance interventions for this population.

Strengths and limitationsThis study has some strengths to highlight. First, it provides new insight into the Latin American region, as parental alcohol misuse and its potential harm to mental health have mainly been studied in English-speaking, high-income countries. Second, it has a large sample size, including over two thousand participants from three of the biggest capital cities in South America.

However, the study also had limitations. Given this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot argue causality between parental alcohol misuse and the proposed outcomes. We also relied on a convenience sample, which may lead to biases. Although participants had an equal chance of being classified as cases, the controls were not chosen systematically and were recruited from diverse settings. Additionally, self-reporting may lead to inaccuracies and social desirability bias when reporting the event. Another limitation is that we did not account for the possibility of simultaneous depression and anxiety symptoms in the analysis. However, the number of participants who reported only one condition was too small to justify a separate analysis. Finally, parental alcohol misuse often overlaps with other factors of household dysfunction (i.e. violence, lack of parental monitoring, neglect), which may moderate or mediate the association between the event and the outcomes and were not considered in the analysis.

ConclusionsYoung people and adolescents from deprived areas in Bogotá, Lima and Buenos Aires who have previously experienced parental alcohol misuse are more likely to have symptoms of both depression and anxiety than people who have not, particularly if the event happened in the last year. It also increases their odds of drinking alcohol more frequently than people who did not experience the event. Additionally, while coping strategies may have an effect on the previous outcomes, they do not modify the impact of experiencing parental alcohol misuse. Preventive interventions should aim to bring awareness, reduce the incidence of youth drinking, and promote positive parenting practices. Future research on protective factors among this population is crucial to further promote mental well-being.

FundingThis work was supported by the Medical Research Council [grant number MR/S03580X/1].

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank all participants of the study for sharing their data, experiences and views with us.