Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in young people from urban neighbourhoods in Latin America (OLA)

Más datosTo evaluate the association between having a relative or partner with a severe illness or injury and symptoms of depression and anxiety, and to explore whether perceived social support modifies this relationship.

MethodsThis case–control study focuses on young people aged 15–16 and 20–24 living in deprived areas of Buenos Aires, Bogotá, and Lima. Depression and anxiety symptoms were measured using PHQ-8 and GAD-7. Logistic regression models were used, stratified by levels of perceived social support.

ResultsAmong 2342 participants, those with a severely ill or injured relative or partner had increased odds of reporting depression and anxiety symptoms. When the event occurred in the last year, low perceived social support was linked to higher odds of depression (OR=5.08) and anxiety (OR=2.89). High support reduced only the risk of depression symptoms.

ConclusionsThese findings align with evidence from other international contexts and highlight the importance of early interventions in situations involving serious health problems of relatives or a partner. Strengthening social support may buffer the psychological impact caused by such events.

Evaluar la asociación entre tener un familiar o pareja con una enfermedad o lesión grave y la presencia de síntomas de depresión y ansiedad, y explorar si el soporte social percibido modifica esta relación.

MétodosEstudio caso-control con jóvenes de edades 15-16 y 20-24años que viven en zonas desfavorecidas de Buenos Aires, Bogotá y Lima. Se midieron síntomas de depresión y ansiedad con los instrumentos PHQ-8 y GAD-7. Se emplearon modelos de regresión logística estratificados por niveles de apoyo social percibido.

ResultadosDe los 2343 participantes, aquellos que tenían un familiar o pareja gravemente enfermo o lesionado presentaron mayor probabilidad de reportar síntomas de depresión y ansiedad. Cuando el evento ocurrió en el último año, un bajo soporte social percibido se asoció con mayor riesgo de depresión (OR=5,08) y ansiedad (OR=2,89). Un alto nivel de apoyo percibido solo redujo el riesgo de síntomas depresivos.

ConclusionesLos hallazgos coinciden con la evidencia de otros contextos internacionales y subrayan la importancia de intervenciones tempranas ante problemas graves de salud en familiares o en la pareja. Reforzar el soporte social podría ayudar a mitigar el malestar emocional asociado a este tipo de eventos.

During adolescence and young adulthood, individuals undergo significant emotional and psychological development. Adolescence is marked by changes in identity and interpersonal relationships.1 Young adulthood involves self-exploration in areas such as professional career, work, lifestyle, and romantic relationships.2 These stages can become particularly challenging when a family member experiences a critical health condition, such as a severe illness or injury.3–5 Such events can negatively affect the mental health of young people.6,7

In economically disadvantaged settings, coping with a relative's severe health is often more difficult. The absence of fully funded healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) adds financial strain to families.8 In Latin America, where family caregivers are the primary source of care for dependents,9 an estimated 1.9 billion hours are spent annually on caring for ill relatives, equivalent to a monetary cost of USD 3.9 billion for non-communicable diseases in the region.10 During the COVID-19 pandemic, overwhelmed healthcare systems and limited medical resources further intensified these challenges.

Young people with a severely ill relative face increased risk of mental11 and physical health problems.4 Adolescents in this situation often experience emotional distress, disruptions to their daily and social activities, and reduced time with loved ones.12 Many also take on caregiving responsibilities to support the family and the affected person.3,13 These responsibilities have been linked to adverse outcomes, including depression, anxiety, loneliness, sleeping problems, physical strain, and illness.14

Families caring for an ill relative often lack sufficient support from extended family or friends.15,16 Young people in this role frequently report needing more support from their social networks.3 Social support has been shown to buffer the impact of stressful events.17 For example, adolescents dealing with a family member's cancer who receive support from other relatives show greater resilience, better functioning, and reduced anxiety.8 Similarly, when a loved one is hospitalised, higher levels of perceived social support can significantly alleviate depressive symptoms.18

Despite the emotional and financial burden that a relative's illness places on low-income families and young people, few studies in Latin America have examined its mental health impact or the protective role of social support. This study evaluates the association between having a relative or partner with a severe illness or injury and symptoms of depression and anxiety at two time points: within the last year or more than a year ago. It also explores whether perceived social support serves as an effect modifier in this association among youth living in low-income communities in South America.

MethodsDesign and settingThis study used a case–control design. Cases were participants with symptoms of depression and anxiety indicated by a score of 10 or higher on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8)19 and/or the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7),20 while the controls were those scoring below 10 on both scales. These instruments are recognised for their sensitivity in identifying clinical symptoms of depression21 and anxiety,22 although the scores do not constitute a formal diagnosis according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) criteria.

The study drew on data from a research programme called “Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in young people from deprived urban neighbourhoods in Latin America (OLA Programme)”.23 The OLA Programme follows a cohort of young people with symptoms of depression and anxiety living in three major Latin American capital cities: Buenos Aires (Argentina), Bogotá (Colombia), and Lima (Peru). This article is based on baseline data collected between April 2021 and November 2022.

ParticipantsEligibly criteria included: (1) living in the 50% most deprived areas of Buenos Aires, Bogotá, and Lima; (2) being 15–16 years old (adolescents) or 20–24 years old (young adults); and (3) providing written informed consent or assent (adolescents), along with parental or legal guardian consent for adolescents. Exclusion criteria were (1) a diagnosis of a severe mental disorder (e.g., psychosis, bipolar disorder), (2) learning disability, and (3) illiteracy.

During recruitment, the OLA Programme enrolled participants with and without symptoms of depression and anxiety. They were screened using PHQ-8 and the GAD-7. The aim was to recruit 2040 participants, including 1020 (340 per city) who scored ten or higher on either screening tool. To address challenges in recruiting males and to avoid overrepresentation of females, we ensured that at least one-third of the participants were male.

Participants were recruited during the COVID-19 pandemic, following country-specific public health restrictions. Depending on local regulations, different feasible strategies were applied in each city. Convenience sampling was used in educational and community settings. Additional recruitment details are presented elsewhere.23,24

ProceduresIndividuals who met the inclusion criteria were invited to complete an online or paper-based self-reported questionnaire. Assessments were conducted individually or in groups, lasted 30–60min, and were supervised by a trained researcher. Responses were recorded using REDCap25; for paper-based questionnaires, responses were manually entered into REDCap.

Variables and instrumentsDependent variablesDepressive symptoms: The PHQ-819 is an 8-item questionnaire assessing depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (no days) to 3 (almost every day or 12+ days). Total score ranged from 0 to 24; scores≥10 indicate clinical symptoms. The PHQ-8 align with DSM criteria and has been validated in Latin American youth.26 In this sample, it showed adequate psychometric properties.27

Anxiety symptoms: The GAD-720 is a 7-item questionnaire measuring anxiety symptoms over the past two weeks. It uses a 4-point Likert scale; total scores range from 0 to 21, with ≥10 indicating clinical symptoms. The GAD-7 reflects DSM criteria for generalised anxiety disorder, and has been used in Latin American youth.28 In this sample, it demonstrated adequate psychometric properties.27

Independent variableRelatives or a partner with severe illness or injury: This was measured using an item from the adapted Adolescent Appropriate Life Events Scale,29 which includes 30 stressful events. The item used was: “Your parents/carer/siblings/partner/children had a severe illness or injury (e.g., life-threatening or impacting their daily life) or surgery”. Response options were (1) never experienced it, (2) experienced it more than a year ago, and (3) experienced it in the last year.

Effect modifierPerceived social support: Measured with the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS),30 which assesses perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others (4 items each). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The total score is the average across all items, ranging from 0 to 7. For the analysis, scores were categorised into tertiles: low (1–2.9), moderate (3–5), and high (5.1–7).

Confounding variablesThese included: country (Argentina, Colombia, and Peru), gender (male, female), age group (15–16 years and 20–24), main occupation (work, study, homemakers, no current occupation), household crowding (>2 persons per bedroom vs. ≤2), severe COVID-19 illness of a relative (yes, no), and perceived social support (low, moderate, and high).

Data analysisWe conducted data cleaning and analysis using Stata.31 Participants with any missing data on variables of interest were excluded. We described each variable using frequencies and proportions related to depression and anxiety symptoms.

To examine the association between a relative's or partner's severe illness and symptoms of depression and anxiety, we estimated crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) using logistic regression with confidence intervals (95% CI). The adjusted model included all confounders listed above.

We also stratified analysis by levels of perceived social support and used a Wald test for trends to assess linear patterns across social support categories. Multicollinearity was evaluated using the variance inflation factor, with a tolerance threshold of <5.

Ethical considerationsThis research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Universidad de Buenos Aires on October 2nd, 2020, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana on November 20th, 2020 (FM-CIE-1138-20), and Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia on November 16th, 2020 (Constancia 581-33-20), and Queen Mary University of London, on November 16th, 2020 (QMERC2020/02). Informed consent was obtained in all three cities. Adolescents provided assent, and their legal guardian/parent provided consent.

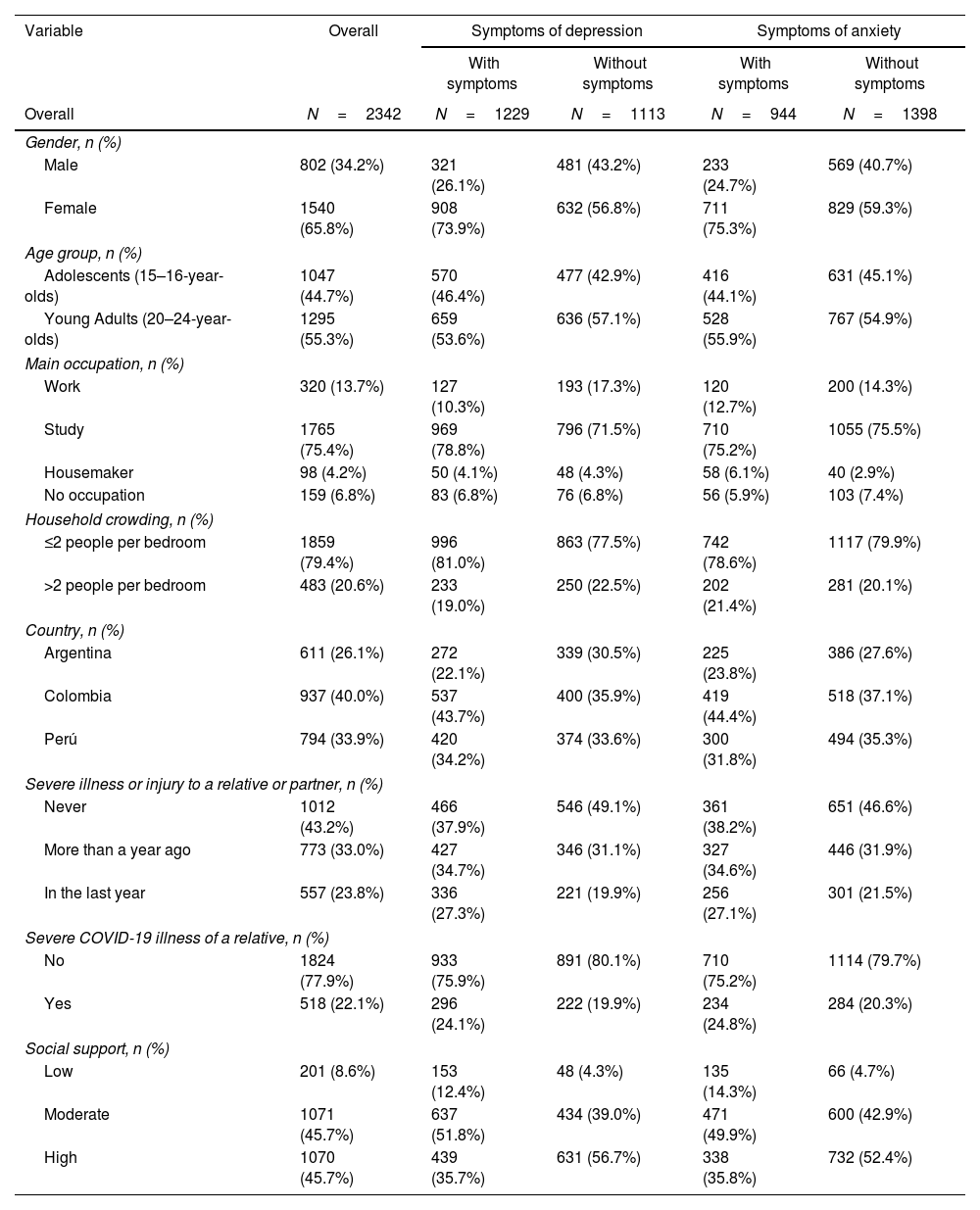

ResultsParticipants’ characteristicsWe collected data from 2402 participants. However, 60 were excluded due to missing values on variables of interest, leaving a final sample of 2342 participants. Among them, 33% reported having relatives or a partner who had been severely ill or injured more than a year ago, and 28.3% within the last year.

26.1% of participants had symptoms of depression (PHQ-8≥10), and 24.7% reported symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7≥10). Table 1 shows the proportion of depression and anxiety symptoms by participant characteristics. Subgroup variations are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics by symptoms of depression and anxiety.

| Variable | Overall | Symptoms of depression | Symptoms of anxiety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With symptoms | Without symptoms | With symptoms | Without symptoms | ||

| Overall | N=2342 | N=1229 | N=1113 | N=944 | N=1398 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 802 (34.2%) | 321 (26.1%) | 481 (43.2%) | 233 (24.7%) | 569 (40.7%) |

| Female | 1540 (65.8%) | 908 (73.9%) | 632 (56.8%) | 711 (75.3%) | 829 (59.3%) |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||

| Adolescents (15–16-year-olds) | 1047 (44.7%) | 570 (46.4%) | 477 (42.9%) | 416 (44.1%) | 631 (45.1%) |

| Young Adults (20–24-year-olds) | 1295 (55.3%) | 659 (53.6%) | 636 (57.1%) | 528 (55.9%) | 767 (54.9%) |

| Main occupation, n (%) | |||||

| Work | 320 (13.7%) | 127 (10.3%) | 193 (17.3%) | 120 (12.7%) | 200 (14.3%) |

| Study | 1765 (75.4%) | 969 (78.8%) | 796 (71.5%) | 710 (75.2%) | 1055 (75.5%) |

| Housemaker | 98 (4.2%) | 50 (4.1%) | 48 (4.3%) | 58 (6.1%) | 40 (2.9%) |

| No occupation | 159 (6.8%) | 83 (6.8%) | 76 (6.8%) | 56 (5.9%) | 103 (7.4%) |

| Household crowding, n (%) | |||||

| ≤2 people per bedroom | 1859 (79.4%) | 996 (81.0%) | 863 (77.5%) | 742 (78.6%) | 1117 (79.9%) |

| >2 people per bedroom | 483 (20.6%) | 233 (19.0%) | 250 (22.5%) | 202 (21.4%) | 281 (20.1%) |

| Country, n (%) | |||||

| Argentina | 611 (26.1%) | 272 (22.1%) | 339 (30.5%) | 225 (23.8%) | 386 (27.6%) |

| Colombia | 937 (40.0%) | 537 (43.7%) | 400 (35.9%) | 419 (44.4%) | 518 (37.1%) |

| Perú | 794 (33.9%) | 420 (34.2%) | 374 (33.6%) | 300 (31.8%) | 494 (35.3%) |

| Severe illness or injury to a relative or partner, n (%) | |||||

| Never | 1012 (43.2%) | 466 (37.9%) | 546 (49.1%) | 361 (38.2%) | 651 (46.6%) |

| More than a year ago | 773 (33.0%) | 427 (34.7%) | 346 (31.1%) | 327 (34.6%) | 446 (31.9%) |

| In the last year | 557 (23.8%) | 336 (27.3%) | 221 (19.9%) | 256 (27.1%) | 301 (21.5%) |

| Severe COVID-19 illness of a relative, n (%) | |||||

| No | 1824 (77.9%) | 933 (75.9%) | 891 (80.1%) | 710 (75.2%) | 1114 (79.7%) |

| Yes | 518 (22.1%) | 296 (24.1%) | 222 (19.9%) | 234 (24.8%) | 284 (20.3%) |

| Social support, n (%) | |||||

| Low | 201 (8.6%) | 153 (12.4%) | 48 (4.3%) | 135 (14.3%) | 66 (4.7%) |

| Moderate | 1071 (45.7%) | 637 (51.8%) | 434 (39.0%) | 471 (49.9%) | 600 (42.9%) |

| High | 1070 (45.7%) | 439 (35.7%) | 631 (56.7%) | 338 (35.8%) | 732 (52.4%) |

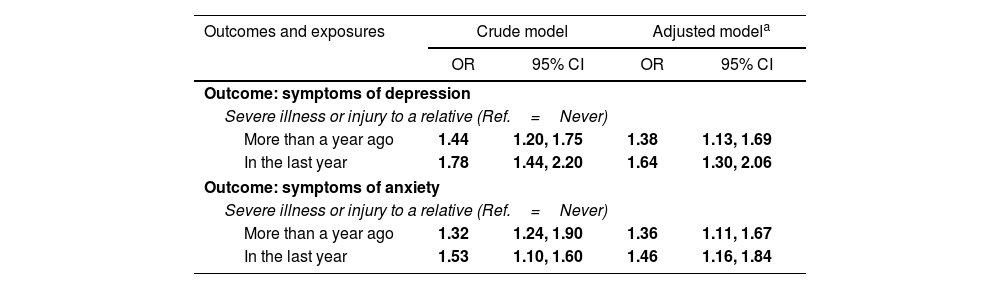

Having a relative or partner with a severe illness or injury was associated with increased odds of having depression and anxiety symptoms, even after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and perceived social support (Table 2).

Crude and adjusted logistic regressions for the association between severe illness or injury to a relative and depression and anxiety symptoms.

| Outcomes and exposures | Crude model | Adjusted modela | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Outcome: symptoms of depression | ||||

| Severe illness or injury to a relative (Ref.=Never) | ||||

| More than a year ago | 1.44 | 1.20, 1.75 | 1.38 | 1.13, 1.69 |

| In the last year | 1.78 | 1.44, 2.20 | 1.64 | 1.30, 2.06 |

| Outcome: symptoms of anxiety | ||||

| Severe illness or injury to a relative (Ref.=Never) | ||||

| More than a year ago | 1.32 | 1.24, 1.90 | 1.36 | 1.11, 1.67 |

| In the last year | 1.53 | 1.10, 1.60 | 1.46 | 1.16, 1.84 |

OR=odds ratio 95% CI=95% confidence interval.

Participants who experienced this situation more than a year ago had 38% increased odds of reporting depressive symptoms, while those who experienced that scenario within the last year had a 64% increase, both compared to those who never faced such an event. Similarly, for anxiety symptoms, participants exposed to this event over a year ago had a 36% increase in odds, whereas for those exposed in the last year, the increase was 46% increased odds, compared to those never experienced the event.

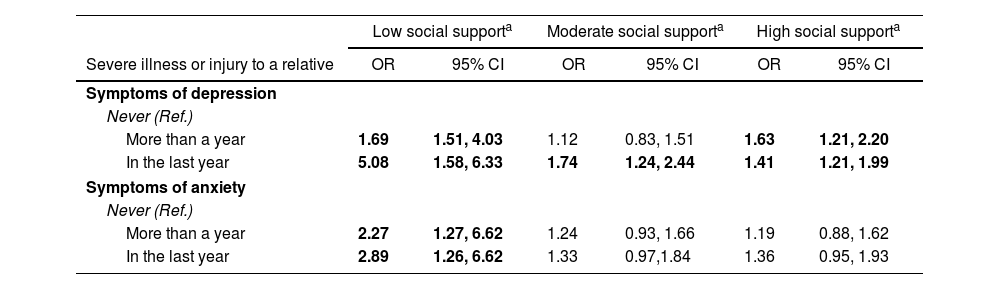

Interaction between severe illness or injury of relatives or a partner and perceived social supportInteraction analysis (Table 3) showed that higher levels of perceived social support were associated with progressively lower odds of depressive symptoms. Among participants who experienced the event more than a year ago, the odds were 1.69 (95% CI: 1.51, 4.03) with low support, and 1.63 (95% CI: 1.21, 2.20) with high support. When the event occurred within the past year, the odds were 5.08 (95% CI: 1.58, 6.33) with low support, and 1.41 (95% CI: 1.21, 1.99) with high support.

Odds ratios of the interaction between severe illness or injury to a relative and levels of social support with symptoms of depression.

| Low social supporta | Moderate social supporta | High social supporta | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe illness or injury to a relative | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Symptoms of depression | ||||||

| Never (Ref.) | ||||||

| More than a year | 1.69 | 1.51, 4.03 | 1.12 | 0.83, 1.51 | 1.63 | 1.21, 2.20 |

| In the last year | 5.08 | 1.58, 6.33 | 1.74 | 1.24, 2.44 | 1.41 | 1.21, 1.99 |

| Symptoms of anxiety | ||||||

| Never (Ref.) | ||||||

| More than a year | 2.27 | 1.27, 6.62 | 1.24 | 0.93, 1.66 | 1.19 | 0.88, 1.62 |

| In the last year | 2.89 | 1.26, 6.62 | 1.33 | 0.97,1.84 | 1.36 | 0.95, 1.93 |

a Adjusted by country, gender, age group, main occupation, household crowding, and severe COVID-19 illness of a relative.

For anxiety, the odds for participants with low support were 2.27 (95% CI: 1.27, 6.62) when the event occurred more than a year ago, and 2.89 (95% CI: 1.26, 6.62) when the event happened within the past year. Although the odds of having anxiety symptoms decreased as levels of perceived social support increased, the differences were not significant.

These associations and interactions are illustrated in Fig. 1, which shows the adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for depression and anxiety symptoms, according to the timing of the event and levels of perceived social support. The figure highlights the moderating role of social support.

Adjusted odds ratios by time since relative's severe illness and social support level. Note: Adjusted odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) for symptoms of depression and anxiety, according to time since severe illness or injury of a close relative, stratified by level of perceived social support. Reference category is “Never.”

Having a severely ill relative or partner was associated with higher odds of depressive and anxiety symptoms, particularly when the event was recent. Perceived social support moderated these associations, especially in recent events; low support was linked to higher odds of emotional distress. While greater perceived social support appeared to buffer depression symptoms, its role in anxiety was less consistent.

Comparison with the literatureThese findings align with previous research.32–36 Young people in these situations often experience disrupted family dynamics, assume additional responsibilities (e.g. caregiving, emotional support, household tasks),3,7,13,37 and face limitations on social and personal development.7,38

These constraints may have been intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which introduced further uncertainty, reduced social contact, and amplified concern for vulnerable relatives with pre-existing medical conditions.6,39,40 Data collection took place during this period, which may contribute to the elevated levels of emotional distress observed in the sample.

The psychological impact of severe illness or injury of relatives or a partner was greater when the event occurred recently, supporting previous studies.41–43 During the first months after such a stressful event, individuals are in a more vulnerable position,44–46 with coping mechanisms not yet fully established. Over time, internal and external resources are developed to manage the situation.47 In our study, those who faced that circumstance in the past year had 64% odds of reporting depression symptoms and 46% odds of reporting anxiety symptoms compared to those who never experienced it.

Perceived social support showed a stronger protective effect for depression than for anxiety symptoms, especially when the event was recent. For those with low support, depression odds were five times higher (OR=5.08), and for anxiety, odds were nearly three times higher (OR=2.89). This suggests that social support may be particularly protective when emotional demands are greatest.

Conversely, high support reduced depression odds to 1.41 for recent events, among those who experienced the event in the last year. Support appeared especially effective in mitigating symptoms of depression, characterised by feelings of hopelessness, isolation, and emotional exhaustion.6 Interpersonal support may counteract these symptoms by fostering a sense of connectedness and shared emotional experience, which may relieve such feelings and provide emotional comfort.3,48

However, the buffering effect of perceived social support on anxiety symptoms was less evident, which is not consistent with previous findings.49,50 Anxiety is characterised by heightened arousal, worry, and anticipatory fear,51 which may be less responsive to interpersonal support, especially in settings of chronic social and economic insecurity. Young people living in deprived urban areas are exposed to structural stressors such as financial hardships, violence, and limited access to mental health services.52 In this context, the severe illness of a relative may compound existing stress and anxiety, making it difficult for even strong support networks to mitigate the psychological impact. The pandemic may have further amplified these effects.53

In summary, perceived social support played a different protective role, effective for depression symptoms, but less so for anxiety symptoms. This suggests that its buffering effect may vary depending on the type of emotional distress and contextual factors.

ImplicationsThe severe illness or injury of a relative or partner has substantial mental health consequences for young people. Despite their influence on emotional well-being, educational trajectories, and future aspirations,14,54 these effects are often overlooked in low-income settings. The study expands existing evidence on the emotional cost of family or a partner's illness in structurally disadvantaged Latin American contexts.

Strengthening social support systems is critical to mitigating the psychological effects of such events. Support from peers,55 family members,56 and community-based programmes57 can reduce depression risk when the stressful event occurred recently. National initiatives in Argentina and Colombia58,59 could be adapted for youth facing family crises. Similarly, school-based tutoring programmes in Peru, Colombia and Argentina60–62 could help to identify and support affected students.

Community-based artistic and sports groups also represent valuable informal support systems. Young people from low-income backgrounds identified these spaces to build friendship and expand social networks.63 Strengthening such initiatives may offer a cost-effective strategy to promote mental well-being and prevent emotional distress from progressing into more severe mental health conditions.

Strengths and limitationsThe study's strengths lie in its substantial sample size, which includes just over a thousand adolescents and young adults from underrepresented, deprived urban areas. Additionally, we have gathered new evidence in the LAC region on the differing impact of having a family member or partner with a severe illness or injury within the past year versus more than a year ago on depression and anxiety symptoms.

Regarding limitations, the link between having a severely ill family member or partner and comorbid symptoms of depression and anxiety was not considered in the analysis, which may underestimate the influence of this stressful event on young people's mental health. Then, while we examined the association between the stressful event and the symptoms of depression and anxiety, we did not differentiate between whether the ill relative is a parent or a sibling. Exploring these potential differences could be valuable in future research.

ConclusionsThe severe illness or injury of relatives or a partner is strongly linked with symptoms of depression and anxiety among young people from disadvantaged economic settings. Perceived social support can serve as a protective factor against the negative emotional impact, especially for depressive symptoms, though its effect is less consistent for anxiety symptoms. This highlights the need for tailored approaches based on the type of emotional response.

Strengthening formal and informal support networks is important for buffering the emotional distress caused by a family or a partner's health crises. Connecting young people to psychosocial support initiatives and community resources, particularly in the early stages of such an event, may be effective. In deprived settings, initiatives such as arts and sports groups can provide accessible and low-cost strategies for mental health.

FundingThis work was supported by the Medical Research Council [grant number MR/S03580X/1].

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We acknowledge all the adolescents and young adults who participated in the OLA. We also extend our gratitude to the researchers involved in the programme: Mauricio Toyama, Liliana Hidalgo-Padilla, Daniela Ramirez-Meneses, Heidy Sanchez, Jimena Rivas, Jenny Bejarano, Noelia Cusihuaman, Ángela Flórez-Varela, Laura Cruz Marin, María Paula Jassir Acosta, Sandra Milena Cañón Gonzalez, María Camila Roldán Bernal, Miguel Esteban Uribe, David Niño-Torres, Bryan Murillo, Juana Valentina Moreno Rojas, Natalia Godoy-Casasbuenas.