The beliefs and opinions of the general population are based substantially on mass media, which often equates mental disorders with violence and criminality. These stigmatising depictions contribute to the development and persistence of negative attitudes towards people with psychiatric conditions. The objective was to examine, through popular music, the subcultural representations of crime and violence in the context of mental disorders, focusing on depictions of victims and offenders.

MethodsStrategy of analysis: Content analysis of Spanish punk lyrics (1981-2010) with references to violent and criminal behaviour associated with mental disorders.

Results257 Spanish punk bands were identified. The discographies included 7,777 songs, of which 190 were related to aggression, violence, or crime. A predilection for violent crimes and descriptions of the perpetrator as “mentally disturbed” was observed. Although they were present, psychotic symptoms were not the main psychiatric symptoms associated with violent crime, but instead it was substance use, antisocial personality traits and paraphilic behaviour. There was less attention paid to victims than to perpetrators.

ConclusionsThe relationships between mental disorders and criminality/violence are overemphasised in the analysed subculture. A positive connotation of social deviance and violent content (particularly serial murder) in service to the provocative nature of this type of music was observed.

Las creencias y opiniones de la población descansan, en gran medida, en los medios de comunicación de masas, los cuales suelen equiparar los trastornos mentales a la violencia y la criminalidad, con lo que se contribuye a la estigmatización de este colectivo. El objetivo es examinar a través de la música popular las representaciones subculturales de las víctimas y los perpetradores de crímenes o violencia relacionados con los trastornos mentales.

MétodosAnálisis de contenido de las letras de canciones punk españolas (1981-2010) con referencias a conductas violentas o criminales aparejadas a los trastornos mentales.

ResultadosSe identificaron 257 grupos punk españoles, cuyas discografías incluyeron un total de 7.777 canciones, de las cuales 190 estuvieron relacionadas con la agresión, la violencia o el crimen. Se evidenció una predilección por los crímenes violentos y descripciones del perpetrador como “perturbado mental”. Aunque presentes, los síntomas psicóticos no fueron los principales síntomas psiquiátricos relacionados con los delitos violentos, sino el consumo de sustancias, los rasgos antisociales de la personalidad y las conductas parafílicas. Las descripciones de las víctimas fueron marginales.

ConclusionesLas relaciones entre los trastornos mentales y la criminalidad o la violencia aparecieron sobredimensionadas en las canciones punk españolas. Se apreció una connotación positiva de la desviación social y los contenidos violentos al servicio de la naturaleza provocativa de este tipo de música.

According to previous reports, violence and criminality are recurrent in the mass media depictions of people with mental disorders.1–4 Besides the contribution of such stigmatising descriptions to the development and persistence of negative attitudes towards people with psychiatric conditions, the connections between violence, crime, and mental disorder have been the subject of debate in the scientific literature.5–22

Different media contribute to a stigmatised perception of mental illness and psychiatric practice.1,4,23–25 However, descriptions in music are still poorly explored. It is so despite the ubiquitous nature of popular music, which turns it into a suitable and accessible source for addressing the beliefs of the general population.26

The implications of research in this field lie in the potential impact of stigmatising depictions on negative attitudes in the general population, support for mental health policies, or help-seeking in individuals with mental disorders.27–40 In this regard, there are mental health initiatives to engage with media to promote more balanced views of people with mental disorders (e.g. Mental Health Media Partnership and the Institute for Mental Health Initiatives in the US or SANE, a mental health advocacy and education organisation, in the UK and Australia).41

To approach popular notions of violence and criminality associated with mental disorders, we focused on their cultural descriptions. Specifically, the conceptions inhabiting the lyrical-musical discourses of popular music. In this regard, the usefulness of the study of punk music has been previously discussed.42,43 Although several studies focus on descriptions of mental disorders in music, none have specifically explored violence and criminality.44–58 The present study aims to fill this knowledge gap to extend the findings from other manifestations of popular culture.29,33,34,59–66

Thus, our objective was to describe the representations of crime and violence associated with mental disorders. Specifically, the aim was to delineate a subcultural portrait of perpetrators and victims.

MethodsContent analysis is an inductive approach pertinent for addressing the research question keeping aside previous theoretical frameworks. It implies two levels of complexity: descriptive and inferential67,68.

Data sources, selection, and collectionThe analysis focused on the lyrics of Spanish punk songs recorded between 1981 and 2010. For purposive sampling, web resources, bibliographic and documentary references were consulted.69–74 It led to an inclusive list of bands whose discographies were examined. Instrumental pieces, musicalised poems, covers, and lyrics in a language other than Spanish were excluded. Repeated songs were considered only once.

Subsequently, two independent codifiers examined the psychiatry-related song lyrics, looking for references to aggression, violence, or crime. Those songs were included for content analysis, reaching thematic saturation.

Codification and analysisThe units of analysis were named “reference.” Each “reference” was constituted by one phrase or sentence related to the topics of interest. The whole song was the context unit and may contain one or more references. Quantitatively, repeated references (e.g., chorus or refrain) were counted once.

Coding ran alongside data collection. The nature of the research problem required the data themselves to model the emergent codes through a recursive process. In vivo coding was used as a first approach, followed by the data organisation into discrete categories. Thus, categories emerged from the data and were refined subsequently by iteration.

Basic descriptions were discussed by the authors, condensing similar or redundant codes. Additionally, new themes were incorporated as they emerged from the text through an open codification process.

A piloting process was conducted to identify potential difficulties. The procedure informed changes to the coding rules. Further piloting was conducted until achieving satisfactory codes. The iterative nature of the process served to enhance the methodological integrity.

A descriptive quantitative analysis addressed the extent of contents by using frequency measures.

ResultsThe process resulted in 257 bands whose 7777 songs were listened to, identifying and transcribing all the pieces with references to psychiatry or mental health problems. Of them, 190 were related to aggression, violence, or crime.

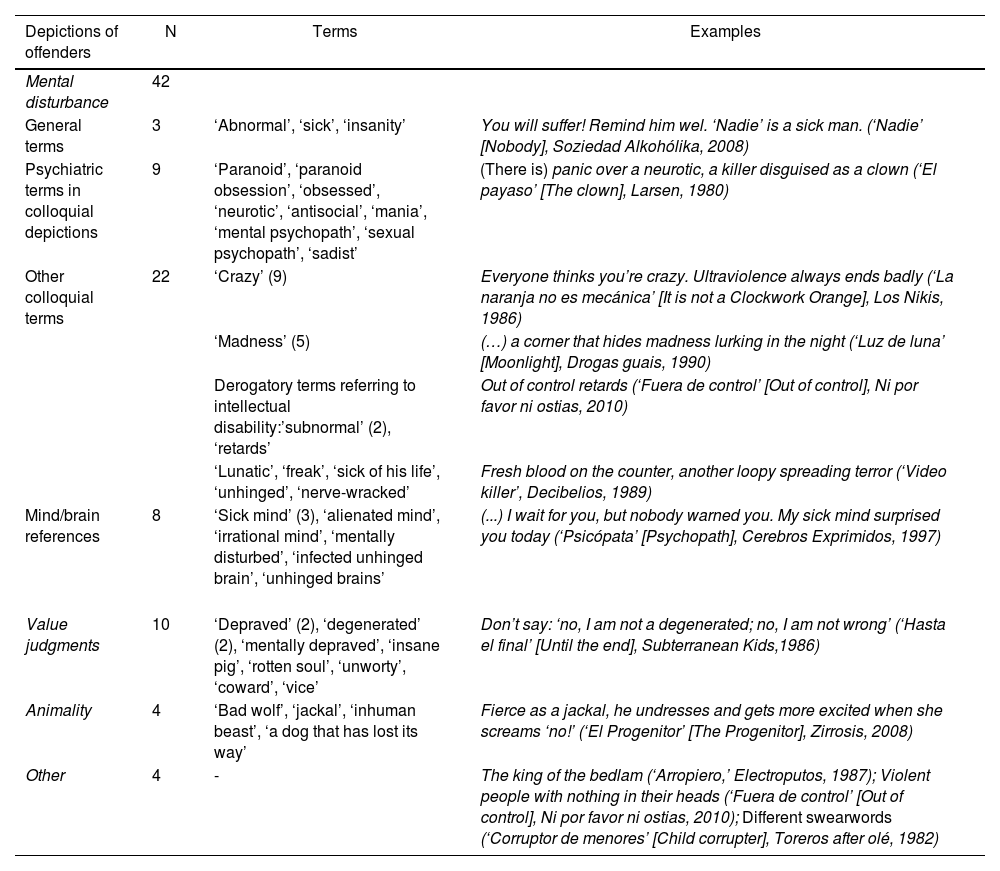

“Abnormals, mad, and degenerated:” the offender in Spanish punkAs expected, the phrases describing offenders included mostly references to mental disturbance (Table 1). These findings are expectable if we attend to the fact that the study focused on songs with themes linked to psychiatry and mental disorders. However, people suffering from mental health conditions could be portrayed as victims, but it was not the case. Thus, it seems that for the analysed subculture, it is difficult to conceive that serial and sexual murders could be perpetrated by “sane” people.

Depictions of the offender in 190 Spanish punk songs (1981-2010).

| Depictions of offenders | N | Terms | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental disturbance | 42 | ||

| General terms | 3 | ‘Abnormal’, ‘sick’, ‘insanity’ | You will suffer! Remind him wel. ‘Nadie’ is a sick man. (‘Nadie’ [Nobody], Soziedad Alkohólika, 2008) |

| Psychiatric terms in colloquial depictions | 9 | ‘Paranoid’, ‘paranoid obsession’, ‘obsessed’, ‘neurotic’, ‘antisocial’, ‘mania’, ‘mental psychopath’, ‘sexual psychopath’, ‘sadist’ | (There is) panic over a neurotic, a killer disguised as a clown (‘El payaso’ [The clown], Larsen, 1980) |

| Other colloquial terms | 22 | ‘Crazy’ (9) | Everyone thinks you’re crazy. Ultraviolence always ends badly (‘La naranja no es mecánica’ [It is not a Clockwork Orange], Los Nikis, 1986) |

| ‘Madness’ (5) | (…) a corner that hides madness lurking in the night (‘Luz de luna’ [Moonlight], Drogas guais, 1990) | ||

| Derogatory terms referring to intellectual disability:’subnormal’ (2), ‘retards’ | Out of control retards (‘Fuera de control’ [Out of control], Ni por favor ni ostias, 2010) | ||

| ‘Lunatic’, ‘freak’, ‘sick of his life’, ‘unhinged’, ‘nerve-wracked’ | Fresh blood on the counter, another loopy spreading terror (‘Video killer’, Decibelios, 1989) | ||

| Mind/brain references | 8 | ‘Sick mind’ (3), ‘alienated mind’, ‘irrational mind’, ‘mentally disturbed’, ‘infected unhinged brain’, ‘unhinged brains’ | (...) I wait for you, but nobody warned you. My sick mind surprised you today (‘Psicópata’ [Psychopath], Cerebros Exprimidos, 1997) |

| Value judgments | 10 | ‘Depraved’ (2), ‘degenerated’ (2), ‘mentally depraved’, ‘insane pig’, ‘rotten soul’, ‘unworty’, ‘coward’, ‘vice’ | Don’t say: ‘no, I am not a degenerated; no, I am not wrong’ (‘Hasta el final’ [Until the end], Subterranean Kids,1986) |

| Animality | 4 | ‘Bad wolf’, ‘jackal’, ‘inhuman beast’, ‘a dog that has lost its way’ | Fierce as a jackal, he undresses and gets more excited when she screams ‘no!’ (‘El Progenitor’ [The Progenitor], Zirrosis, 2008) |

| Other | 4 | - | The king of the bedlam (‘Arropiero,’ Electroputos, 1987); Violent people with nothing in their heads (‘Fuera de control’ [Out of control], Ni por favor ni ostias, 2010); Different swearwords (‘Corruptor de menores’ [Child corrupter], Toreros after olé, 1982) |

In parenthesis, the number of references to repeated terms (among different songs). As can be noted, a part of colloquial terms was influenced by psychiatric nomenclature. A group of references with obvious moral connotations reached 16.67% (N=10), mainly related to sexual offences.

References to “animality” (“dog,” “wolf,” “jackal”) were found, although in a minority of the cases. In general, comparisons of aggressors to animals were purely descriptive. Thus, the animality was not employed as a metaphor for the psychodynamics of violent or criminal behaviour. It is worth mentioning the use of “bad wolf” and “jackal” as descriptors for perpetrators of sexual crimes, thus underlining the predatory nature of the aggressors. In the same offender profile, the expression “insane pig” also appeared. The moral connotation becomes evident in this case. Besides, the expressions “inhuman beast” or “a dog that has lost its way” were used for antisocial personality traits, being more in tune with the ideas of otherness in the punk subculture.

Motivations, characteristics, and behaviors of serial rapists were poorly depicted, predominating moral connotations.

In general, offenders mainly were depicted as males. Females emerged as the aggressors in only 10 descriptions of homicides and one of serial rape. Portrayals of homicidal behavior in women contained 7 references to murder (3 as revenge or defence from gender-based violence), 2 to homicidal ideation, and 1 to attempted murder-suicide.

Considerations of race or ethnicity were absent in the depictions of violent crimes in our sample.

Allusions to the child behavior of aggressors were found. In one case of homicide, antecedents of childhood trauma were portrayed. Similarly, in one song depicting drug trafficking by a substance user, the musicians alluded to a history of troubled childhood marked by physical and sexual abuse. Sadistic childhood behaviors were also described, e.g., killing and torturing animals. Finally, one song contained depictions of social withdrawal and bizarre behavior in childhood: “he had no friends,” “he played with the corpses of all of his puppets,” “he carried cockroaches in his pockets” (El lunático del quinto piso [The fifth-floor lunatic] by Siniestrosis, 2010).

The emotional states of the offenders were predominantly depicted in school shootings: hate, resentment, anger, humiliation, and incomprehension. The guilt was depicted only in 2 references (related to repeated incestuous sexual abuse and homicide).

The lyrics related to serial murders were more susceptible to trivialisation. These songs were most frequently presented from the aggressor's perspective, showing neutral descriptions of the crime or even a provocative glorification of the violent behavior.

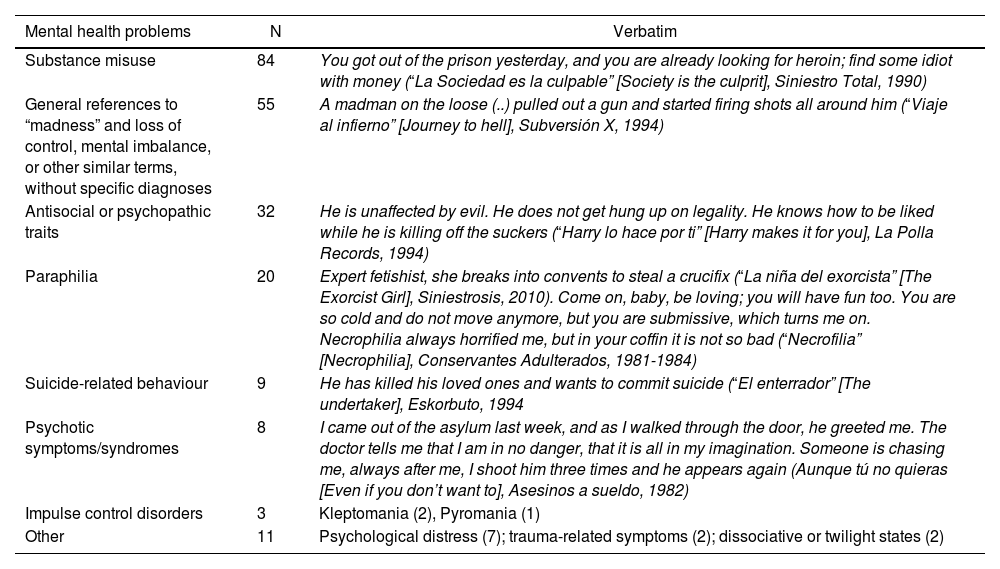

The depictions of criminal or violent behavior in Spanish punk songs included, at a psychopathological level, references to mental symptoms or specific disorders, psychopathic and antisocial traits, and substance use (Table 2).

Distribution of references to mental symptoms or disorders in 190 Spanish punk songs related to criminality or violence (1981-2010).

| Mental health problems | N | Verbatim |

|---|---|---|

| Substance misuse | 84 | You got out of the prison yesterday, and you are already looking for heroin; find some idiot with money (“La Sociedad es la culpable” [Society is the culprit], Siniestro Total, 1990) |

| General references to “madness” and loss of control, mental imbalance, or other similar terms, without specific diagnoses | 55 | A madman on the loose (..) pulled out a gun and started firing shots all around him (“Viaje al infierno” [Journey to hell], Subversión X, 1994) |

| Antisocial or psychopathic traits | 32 | He is unaffected by evil. He does not get hung up on legality. He knows how to be liked while he is killing off the suckers (“Harry lo hace por ti” [Harry makes it for you], La Polla Records, 1994) |

| Paraphilia | 20 | Expert fetishist, she breaks into convents to steal a crucifix (“La niña del exorcista” [The Exorcist Girl], Siniestrosis, 2010). Come on, baby, be loving; you will have fun too. You are so cold and do not move anymore, but you are submissive, which turns me on. Necrophilia always horrified me, but in your coffin it is not so bad (“Necrofilia” [Necrophilia], Conservantes Adulterados, 1981-1984) |

| Suicide-related behaviour | 9 | He has killed his loved ones and wants to commit suicide (“El enterrador” [The undertaker], Eskorbuto, 1994 |

| Psychotic symptoms/syndromes | 8 | I came out of the asylum last week, and as I walked through the door, he greeted me. The doctor tells me that I am in no danger, that it is all in my imagination. Someone is chasing me, always after me, I shoot him three times and he appears again (Aunque tú no quieras [Even if you don’t want to], Asesinos a sueldo, 1982) |

| Impulse control disorders | 3 | Kleptomania (2), Pyromania (1) |

| Other | 11 | Psychological distress (7); trauma-related symptoms (2); dissociative or twilight states (2) |

N: number of references.

The number of references does not equal the number of songs (each song could contain one or more references). There was an overlap between substance use and psychotic symptoms (LSD-induced, 1 reference) and between substance use and antisocial traits (10 references).

In terms of more specific descriptions, allusions to paraphilias or perversion predominated, by frequency: sadism, cannibalism and necrophilia, and masochism/sadomasochism. Other identified paraphilic behaviors included fetishism, zoophilia, paedophilia, necrophagy, and urophagia.

Suicide-related behavior was portrayed in offenders in 9 references (including five cases of murder-suicide). One of the murder-suicide portrayals contained references to depressive symptoms. All of the familicide depictions included references to murder-suicide.

Descriptions of psychotic symptoms accounted for 4.21% of all songs that paired mental disorders with violent and criminal behavior, increasing in frequency in those songs with descriptions of violent crimes (homicidal spectrum, mainly). On the other hand, attributions of causality were more frequent for psychotic symptomatology than other entities.

Psychotic symptoms in offenders included hallucinations (auditive and not specified), thought disorders, paranoid delusion, misidentification syndromes, and LSD-induced psychotic disorder. For its part, the presumption of “irrationality” in psychosis emerged as a tacit cause in one depiction of homicide by lynching. Additionally, the madness as “loss of reason,” attributed to childhood trauma, was linked to one case of multiple, non-serial, homicide. Two additional references described auditive hallucinations among homicide perpetrators without identifying psychotic symptoms as a cause or trigger for murder.

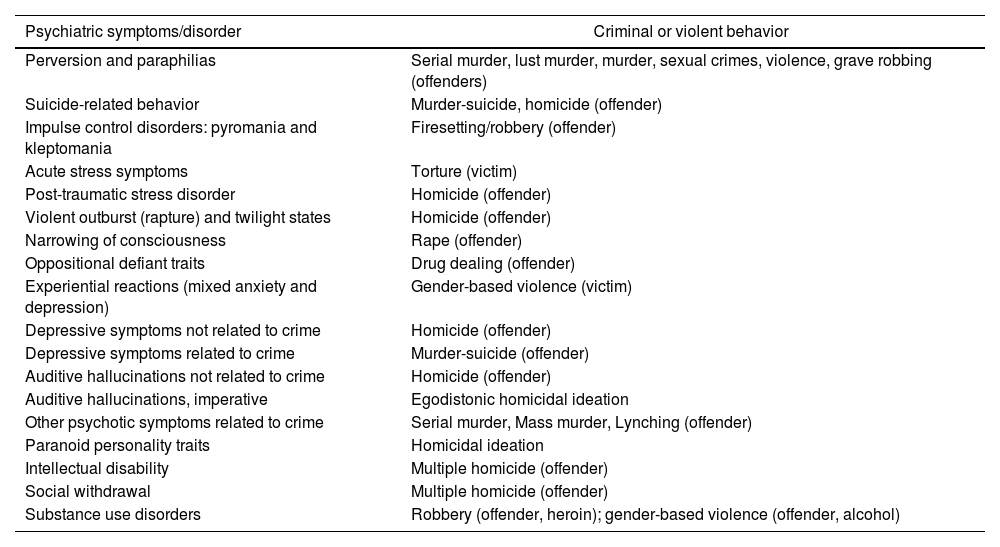

Finally, 3 songs explicitly alluded to impulse control disorders (2 allusions to pyromania and 1 to kleptomania). Other psychiatric symptoms in our sample and their links to violence or criminality are summarised in Table 3.

Psychiatric symptoms and syndromes related to criminal or violent behavior in 190 Spanish punk songs.

| Psychiatric symptoms/disorder | Criminal or violent behavior |

|---|---|

| Perversion and paraphilias | Serial murder, lust murder, murder, sexual crimes, violence, grave robbing (offenders) |

| Suicide-related behavior | Murder-suicide, homicide (offender) |

| Impulse control disorders: pyromania and kleptomania | Firesetting/robbery (offender) |

| Acute stress symptoms | Torture (victim) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | Homicide (offender) |

| Violent outburst (rapture) and twilight states | Homicide (offender) |

| Narrowing of consciousness | Rape (offender) |

| Oppositional defiant traits | Drug dealing (offender) |

| Experiential reactions (mixed anxiety and depression) | Gender-based violence (victim) |

| Depressive symptoms not related to crime | Homicide (offender) |

| Depressive symptoms related to crime | Murder-suicide (offender) |

| Auditive hallucinations not related to crime | Homicide (offender) |

| Auditive hallucinations, imperative | Egodistonic homicidal ideation |

| Other psychotic symptoms related to crime | Serial murder, Mass murder, Lynching (offender) |

| Paranoid personality traits | Homicidal ideation |

| Intellectual disability | Multiple homicide (offender) |

| Social withdrawal | Multiple homicide (offender) |

| Substance use disorders | Robbery (offender, heroin); gender-based violence (offender, alcohol) |

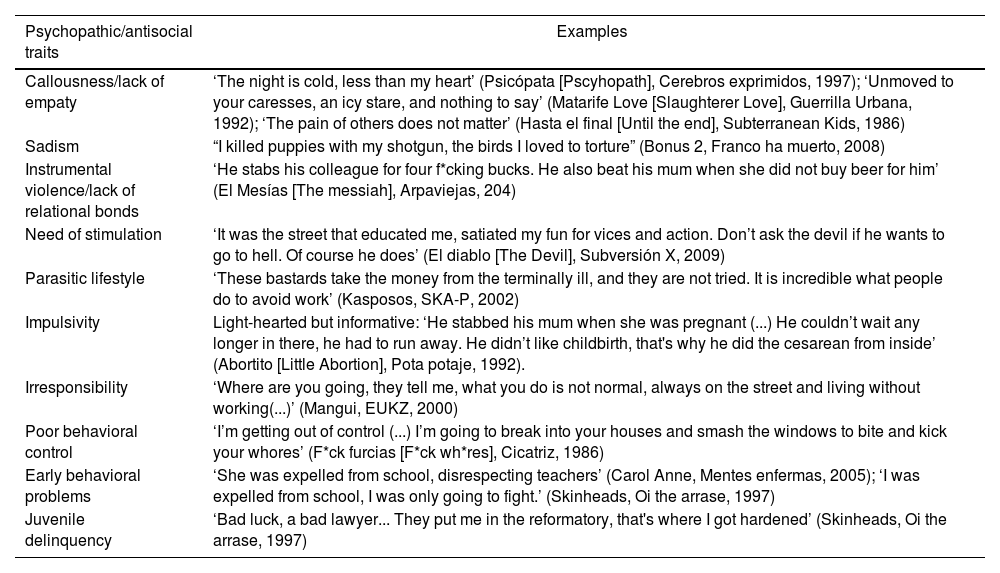

Regarding the personality traits explicitly described in offenders, we found 23 references to antisocial and psychopathic traits (Table 4). There were 2 profiles implicitly characterised by a grandiose sense of self-worth (e.g., “my legacy will remain indelible as the time that my freedom lasts,” in El demonio [The Demon] by BC Bombs, 2009). The first profile, “psychopathic,” focused on the affective facet (Factor 1, according to Hare75); by exhibiting callousness, lack of empathy, sadism, instrumental violence, and lack of relational bonds. This profile was more frequently related to violent crimes (homicide, serial killing, sexual violence, and torture). The second profile, “antisocial,” was focused on the lifestyle and antisocial facets, mostly: need for stimulation, parasitic lifestyle, impulsivity, irresponsibility, poor behavioural control, early behavioural problems, and juvenile delinquency (Factor 275). This profile was related to violence (fighting/beating, vandalism, threats, impulsive aggression), substance use, robbery, and to a lesser extent, sexual assault, drug trafficking, handling stolen goods, fraud, and elder abandonment. Criminal versatility becomes evident in this group.

Examples of psychopathic traits in 23 references from 190 Spanish punk songs related to criminal and violent behavior.

| Psychopathic/antisocial traits | Examples |

|---|---|

| Callousness/lack of empaty | ‘The night is cold, less than my heart’ (Psicópata [Pscyhopath], Cerebros exprimidos, 1997); ‘Unmoved to your caresses, an icy stare, and nothing to say’ (Matarife Love [Slaughterer Love], Guerrilla Urbana, 1992); ‘The pain of others does not matter’ (Hasta el final [Until the end], Subterranean Kids, 1986) |

| Sadism | “I killed puppies with my shotgun, the birds I loved to torture” (Bonus 2, Franco ha muerto, 2008) |

| Instrumental violence/lack of relational bonds | ‘He stabs his colleague for four f*cking bucks. He also beat his mum when she did not buy beer for him’ (El Mesías [The messiah], Arpaviejas, 204) |

| Need of stimulation | ‘It was the street that educated me, satiated my fun for vices and action. Don’t ask the devil if he wants to go to hell. Of course he does’ (El diablo [The Devil], Subversión X, 2009) |

| Parasitic lifestyle | ‘These bastards take the money from the terminally ill, and they are not tried. It is incredible what people do to avoid work’ (Kasposos, SKA-P, 2002) |

| Impulsivity | Light-hearted but informative: ‘He stabbed his mum when she was pregnant (...) He couldn’t wait any longer in there, he had to run away. He didn’t like childbirth, that's why he did the cesarean from inside’ (Abortito [Little Abortion], Pota potaje, 1992). |

| Irresponsibility | ‘Where are you going, they tell me, what you do is not normal, always on the street and living without working(...)’ (Mangui, EUKZ, 2000) |

| Poor behavioral control | ‘I’m getting out of control (...) I’m going to break into your houses and smash the windows to bite and kick your whores’ (F*ck furcias [F*ck wh*res], Cicatriz, 1986) |

| Early behavioral problems | ‘She was expelled from school, disrespecting teachers’ (Carol Anne, Mentes enfermas, 2005); ‘I was expelled from school, I was only going to fight.’ (Skinheads, Oi the arrase, 1997) |

| Juvenile delinquency | ‘Bad luck, a bad lawyer... They put me in the reformatory, that's where I got hardened’ (Skinheads, Oi the arrase, 1997) |

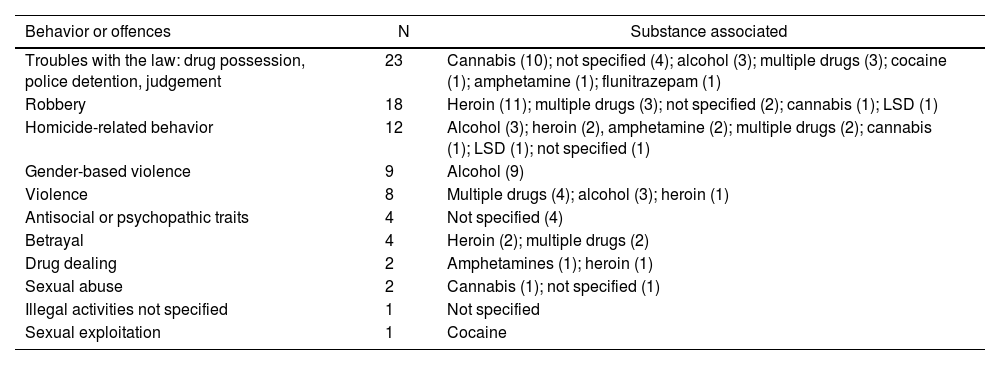

Finally, associations between substance use and crime were recurrent (N=84) (Table 5).

Associations between substance use and violence, crime, or antisocial behaviors.

| Behavior or offences | N | Substance associated |

|---|---|---|

| Troubles with the law: drug possession, police detention, judgement | 23 | Cannabis (10); not specified (4); alcohol (3); multiple drugs (3); cocaine (1); amphetamine (1); flunitrazepam (1) |

| Robbery | 18 | Heroin (11); multiple drugs (3); not specified (2); cannabis (1); LSD (1) |

| Homicide-related behavior | 12 | Alcohol (3); heroin (2), amphetamine (2); multiple drugs (2); cannabis (1); LSD (1); not specified (1) |

| Gender-based violence | 9 | Alcohol (9) |

| Violence | 8 | Multiple drugs (4); alcohol (3); heroin (1) |

| Antisocial or psychopathic traits | 4 | Not specified (4) |

| Betrayal | 4 | Heroin (2); multiple drugs (2) |

| Drug dealing | 2 | Amphetamines (1); heroin (1) |

| Sexual abuse | 2 | Cannabis (1); not specified (1) |

| Illegal activities not specified | 1 | Not specified |

| Sexual exploitation | 1 | Cocaine |

Of note: troubles with the law and cannabis; robbery and heroin use; gender-based violence and alcohol use; violent behaviour and substance use (alcohol, heroin, multiple drugs). Causality cannot be inferred from the depicted associations.

There was less attention paid to victims than to perpetrators. Victims were omitted from the narratives of crimes other than homicide or sexual. In other cases, the typology of the crime itself provided information about the victims (e.g., gender-based violence, child or elder neglect, child sexual abuse).

Except for gender violence and some sexual offences, there was a predominance of desubjectivized descriptions of the victims. The victims of sexual abuse were predominantly adult women and children (13 and 9 references, respectively). Other lyrics did not offer clues about the victims’ ages, but provided information on their relationship with the aggressor: daughter or sister (3 and 1 references, respectively). Finally, 2 cases did not offer information about the victims’ gender, age, or relationship to the offender.

As for the murder victims, their distribution in decreasing order included: couple (N=16; 2 cases of femicide and 3 cases of homicide as defence or revenge related to gender-based violence); family (N=9; 3 cases patricide, 1 case matricide, 1 case parricide, 1 case filicide, 3 cases all family members); children (N=5); neighbours (N=4); employer or boss (N=3); religious people (N=2); older women (N=2); schoolmates (N=2); and other (1 reference in each case: drug dealer, policemen, psychiatric patient, zoophilic priest, fan club members, prostitutes, gas bottle delivery man, kiosk attendant). Thus, most of the victims described in the murders had some relationship with the offender (68.63%).

The emotions and suffering of the victims received little attention, except in cases of gender-based violence, where the dominant narrative was from the victims’ point of view. It was the same for contexts of police torture and child sexual abuse.

Additionally, the idea of revenge and taking justice into one's own hands emerged. The victim becomes the aggressor in these cases, mainly related to gender-based violence or sexual abuse (particularly child sexual abuse). The revenge of the victims included not only the homicide but also the idea of castration as a solution (sexual offences and gender-based violence) and aggression in general.

The emotions described in the victims included predominantly: distress, confusion, and fear. Confusion was recurrent, particularly in cases of child sexual abuse.

DiscussionThe depictions found are closely related to the connotations expected in the general population and the data on media research. Thus, we observe a predilection for violent crimes and frequent allusions to the perpetrator as mentally disturbed.

Although present, psychotic symptoms are not the main psychiatric symptoms associated with violent crime in our dataset, but substance use, antisocial personality traits and paraphilic behaviour.

There is less attention paid to victims than to perpetrators. The former, often appear desubjectivized, except in some cases where the ideological dimension of punk subculture do not allow for trivialisation. Thus, the ideological/moral positioning was a determining factor in depicting gender-based violence, child molestation, and police torture.

Most of the victims of murder described in Spanish punk songs have some relationship with the offender (68.63%). It is consistent with the literature on single homicide and mass murder but not regarding serial killing.76

The greater attention paid to the criminals is concomitant with the almost complete invisibilisation of the victims and their relatives’ suffering. On the one hand, it may be a way of evading ourselves from their tragedy, a defence; on the other hand, the mythologisation of the murderer contributes to neutralising him.77 Thus, it works as a way of reducing the threat of the killer's figure by diverting the focus from the frightful reality of the crime to the carnivalesque realm of fiction.77 In this process of fictionalisation, the reality of the collective victims is lost.77 Further, the evolution of the serial killer's cultural portrayal has shifted from monstrosity to humanisation through narratives that promote an audience's empathetic approach to the killer.77 It has been achieved by reducing spectators’ cognitive dissonance at the expense of victims who “deserve to be killed,” shifting the natural tendency to empathise with the victims towards empathy with the killer constituted as an antihero.77

In general, punk aesthetics and musical aspects contain allusions to mental illness as a representation of its self-marginalisation and the opposition to socially accepted patterns.42 From an ideological perspective, references to crime or violence may be understood in terms of subcultural identity affirmation in punk music: otherness, provocation, and transgression.

In light of the data, it is possible to venture a predominantly negative appreciation of sexual crimes and gender-based violence. It traduces a low tolerance of such crimes in the punk subculture, differing from the more carnivalesque representations of serial killers, perhaps most notably in relation to the psychology and appetites of the perpetrators.

A more positive connotation could be expected towards the contents of social deviance (and even antisocial traits), which may be understood from the subculture's ideological perspective.78 To some extent, other violent contents, particularly serial murders, equally seem to be serving the provocative nature of this type of music rather than an aesthetic enjoyment from depictions of the crime.78 Thus, the figure of the killer (mainly the serial) appears not as a cult character but rather as an instrument for punk transgression. Considering that the serial killer (or spree killer, mass murderer, school shooter, among others) typically fills the role of modern-day bogeyman, it becomes clear that these narratives play a relevant role in the cultural imaginary. Via the “othering” or monsterisation of the perpetrator, they allow the audience to explore danger safely through the comfort and safety of the narrative frame of the text (e.g., literature, films, TV shows).77

Depictions in Spanish punk music versus other cultural artefactsSince this is a very niche topic, there are no previous data in popular music to compare.26 In a quantitative content analysis focused on substance use, 10% of the 276 most popular songs in 2005 (according to the Billboard chart) contained associations with violent behaviour.32 Another study suggests a decrease in the association between alcohol and violent behaviour in rap music (from 20% to 8% between 1979 and 2009).38

The most recent study on American hip-hop included only 125 songs over two decades.43 Again, pieces were selected based on their popularity, with only three specific categories (anxiety, depression and suicide) assessed. The analysis focused on transcripted song lyrics without listening to the phonographic material. Unfortunately, other relevant psychiatric conditions such as substance use disorders or psychosis were not assessed. References to violence or criminality were also not included.

In addition, comparisons with other media studies are problematic since there are differences in the research objectives (production, representation, or reception), the assessed dimensions, how they are defined, selected, and measured, and the comparators.

Data from film and television research suggest that violent acts are more likely to be committed by mentally disturbed characters and at a higher rate than in real life.44,45,47–50,79–84

Mind the gap: Mental disorders and crime or violence in the psychiatric literatureIn light of clinical and forensic data, cruelty to animals in childhood and adolescence is a finding that has been classically associated with physical violence in adulthood.84,85 Ideas of a disturbed childhood are recurrent in horror/thriller films involving serial killers.86 These influences may have permeated into the cultural milieu, being subsequently reproduced by other media, in this case, music. What is certain is that early trauma has garnered much attention in theoretical models of the development of criminal behaviour, mostly murder and its relationships with paraphilias and other perversions.87–92

Regarding emotional states, extreme feelings of anger, social alienation, and desires for revenge have been described among mass murder perpetrators.18,93 Furthermore, the resentment added to ruminating on past humiliations and their subsequent evolution into fantasies of violent revenge is part of the explanatory models for the development of mass murder.74 Also, humiliation has been emphasised as a motivation or trigger for serial murder.94–96 Depression and suicidality have been described among mass shooters,18 and familicide perpetrators are more likely to attempt suicide following the homicide,97 similarly to our findings.

As for socio-demographic factors, the preponderance of male gender in homicide and sexual offences is consistent with available data, locally and internationally.93,98–105 It is one of the few data where Spanish punk music, fiction, news, police records, and epidemiology coincide. Considerations of race or ethnicity were absent in the depictions of violent crimes in our sample. It is a difference from what is known about the coverage of crime by the media in the US, where ethnic minorities are underrepresented as victims and overrepresented as offenders.106

Concerning typologies, the group of serial rapists is more heterogeneous than the serial murderers.107 In contrast, serial rapists were portrayed more homogeneously in Spanish punk, under general depictions of “vice,” “sadism,” or “depravity.” As for conceptualisations of psychopathy, our findings are consistent with clinical observations and research that support the existence of different subtypes of psychopaths.108 Thus, although antisocial and psychopath are considered equivalent terms in some circles, the distinction between true psychopaths and persons with antisocial tendencies makes clinical-forensic sense.109

The associations between substance misuse and violent crime have been previously supported, although it does not imply causality necessarily.110–116 As Raskin states, multiple paths lead to substance use and crime (e.g., acute intoxication, income-generating crime, exposure to drug cultures and drug markets, among others).111 For example, the criminal lifestyle itself is related to increased substance use. On the other hand, common underlying factors are linked to substance use and crime (e.g., neighbourhood, family, personality, genetics).111 The use of alcohol and drugs is a predictor of criminality and criminal recidivism.116

The connections between heroin and crime dominated the debate in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as did the role of methadone programs.112–115 However, more recent findings suggest that the risk of violent crime in opioid users is lower than in other drugs and similar to substance-induced psychotic disorder.110

In light of psychiatric epidemiologic research, some data regarding the proposed relationships between mental disorders and crime or violence should be noted. It is relevant for avoiding misguiding messages from cultural depictions. First, evidence suggests that people with severe mental disorders are at higher risk for violent behaviour than the general population,9,11 including homicide.13,117–120 However, the contribution of psychotic disorders to overall homicides is limited.120 Moreover, the number of such homicides is thought to have declined over the last decades.121 Large population-based studies have shown only a modest relationship between violence and psychoses.10,122 Consequently, many authors argue that it is much more likely that people with severe mental disorders will be victims of violence rather than the perpetrators.10,18

Regarding homicide and mental disorders, great relevance has been given to the comorbidity with substance use and personality disorders (particularly, alcohol use disorders and antisocial personality disorder, respectively)119,123,124 and the non-adherence to treatment in severe mental disorders.123

In general, people with personality disorders present the highest levels of perpetration16 and victimisation.10 Specifically, cluster B and paranoid personality disorders are linked to aggression and violent crimes,14,125 suicidal behaviours, and criminal arrest.126

Additionally, a higher risk of engaging in violence has been described in patients with bipolar disorder.12,127

Concerning depressive disorders, a high rate of filicide (4.5%) has been described in depressive psychoses, whereas episodes without ouvert depression would have lower rates.128 Additionally, the link between depression and murder-suicide is noteworthy,129 and depressive symptoms or suicidal threats have been reported in mass murderers.18

Regarding psychotic disorders, Knoll's classification130 suggests a subtype of mass murder denominated “pseudocommunity-psychotic,” whose main motives would be linked to paranoid delusions. In serial killing, the perpetrators rarely suffer from psychotic disorders.131 According to Hachtel et al.,132 murder is most often motivated by revenge in offenders with psychoses.

Some mediators of violent behaviour in psychotic disorders have been studied, identifying: delusional beliefs (persecution, being spied on, and conspiracy) mediated by anger,6,7 substance use,15 and moral cognition.22 Interestingly, some specific moral cognitions related to psychotic symptoms are associated with a higher risk of violent behaviour (e.g., responding to an act of injustice or betrayal, or the wish to punish impure behaviour).22 Additionally, the research suggests that there is a weak association between mental disorders and violence when there is no comorbid substance abuse.133 In people in the early phases of psychosis, there is a higher risk of violence in individuals with greater impulsivity, emotional instability, hostility, lack of insight, non-adherence to treatment, and comorbid substance use.20

The findings in the literature on violence and schizophrenia are mixed, stemming from differences in quality and design between studies.9

As in any other individual, comorbidity with substance use is associated with a higher risk.15 In this regard, Fazel et al. suggest a higher risk for homicide in psychosis than in the general population.15 However, the risk is highest in people with substance abuse (but without psychosis), and most of the excess of risk in psychosis appears to be mediated by substance abuse comorbidity. Thus, individuals with dual pathology (psychosis and substance abuse) had a similar risk to those with only substance abuse.15

On the other hand, nonspecific factors, mainly of a psychosocial nature, are likely to be overrepresented in people with severe mental disorders (e.g., social marginality or socioeconomic disadvantage), which would better explain the association with violence or criminal behaviour than psychiatric symptoms per se.8,120 Some authors suggest that the association between crime and psychosis is mediated by a higher prevalence of general criminogenic factors in people suffering from severe mental disorders.8,120 Furthermore, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that homicide rates by those diagnosed with schizophrenia are correlated with total homicide rates, which would suggest that there are common etiological factors for homicide.19

On the other side, Honings et al. found that the presence of specific psychotic symptoms (self-reported and clinically validated hallucinations) could differentially predict the perpetration of physical violence, even after adjusting for some contextual confounders (childhood trauma, adverse life events, and social support) and psychopathological dimensions (substance use, bipolar disorder, depression/dysthymia, anxiety, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, behavioral disorder, antisocial personality).17 Nevertheless, although the data suggest specific factors related to psychotic symptomatology, those factors do not explain most of the risk.17 After adjusting for confounding factors, the associations, although significant, were considerably reduced.17

Another relevant aspect is that association does not imply causation. In other words, if an individual with a psychiatric diagnosis perpetrates a crime, it does not necessarily mean that the symptoms of a mental disorder explain such behavior. Although we have mentioned a study that associates specific psychotic symptoms with the risk of violence,17 it has also been shown that there are other factors such as comorbidity and spurious psychosocial elements.8,15,120 In this regard, it has been argued that most crimes perpetrated by people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders or bipolar I disorder may be explained by factors other than their psychiatric symptoms.134 Similarly, it has been suggested that most offenders with a history of mental disorder were not acutely ill or under mental healthcare at the time of the homicide.124 In contrast, the findings of Minero et al. suggest that almost everyone with psychosis had been symptomatic by the time of the crime.135 Despite these discrepancies, the relevance of prevention cannot be ignored.

The study of violence and criminality within mental disorders is a matter as sensitive as it is relevant. Data from research underline the need for a balanced view in which the higher risk of violent behavior in this population is acknowledged as the first step toward its prevention. Likewise, this should be nuanced, keeping in mind that the contribution of severe mental disorders to criminality is low.13

Practical implicationsThe impact of music depictions on the audience is a less-explored area,26,136,137 and it is not unreasonable to hypothesise that probably it is lesser than that of realistic cinematic representations. Like any artistic manifestation, popular songs are both a reflection and an inspiration of the ideas present in the general population.26

Thus, lyrical-musical discourses can metabolise popular ideas and other artistic or cultural sources, giving back new meanings which feed the popular repertoire through a circular process. Descriptions in music likely serve more as a reflection of prevailing stereotypes than as an element that has a decisive impact on audiences’ opinions. Irony and invective in punk can detract from the credibility of its messages as they are often parodies and hyperbolic caricatures;78 however, its intertextual background can contribute to disseminating and reaffirming messages present in other media.78 Additionally, hidden behind the hyperbolic punk provocation, we can find alternative insights into our practices and scope of action.

These aspects are relevant for mental health professionals since insights from popular cultural representations can inform our knowledge about the distortions, myths, and fears of our patients, their families, and society. This information may be relevant in different stages of the clinical encounter and must be taken into account; for example, in the diagnosis disclosure of a mental disorder or even during the prescription of treatment, at which point many of these fears or distortions may arise.

ConclusionsThe negative perceptions of “madness” and “madman” can be mainly explained by the attributions of dangerousness to which they are subjected at the popular level. Thus, a link between madness, violence, and criminality could be presupposed. Our current results show that, although present, psychotic symptoms were not the main psychiatric symptoms related to violent crimes but rather paraphilic behaviors. However, the last ones appeared mostly portrayed as epiphenomena of the perversion attributed to the serial killer profile and not as causal factors of the crime. In contrast, causal relationships between psychotic symptoms and violent crimes were more explicit in the studied songs. More general terms alluding to “mental disturbance” were frequent in the depictions of crime and violence.

Despite some points of convergence between our results and data from criminological, forensic, and epidemiological research, the relationship between mental disorders and violence or criminality continues to be overestimated in Spanish punk music, similarly to other products of popular culture. In the punk songs under investigation in this study, the appeal to the listener is presumably in the boldness and catharsis of the revenge fantasy. To some extent, the sublimation of aggression through music must be weighed against the transmission of content that is, at least in appearance, stigmatising. Thus, it is important to consider that if these narrative trajectories are subverted, such narratives may lose much of their appeal, especially amongst alternative subcultures that identify as social transgressors.

Strengths and limitations of the studyThis study is the first to provide a song lyric-based content analysis of the dimensions of violence and criminality within mental disorders. To our knowledge, this is the most extensive study regarding these depictions in music. Moreover, not even in films (extensively studied regarding psychiatric contents) is there any data on the overall frequency of this type of content over thirty years. Thus, the present study complements findings in other cultural artefacts and fills the knowledge gap in a so-far superficially explored area: the depictions of perpetrators and victims of crime and violence linked to mental disorders.

Besides the volume of data analysed, the in-depth examination of the contents by analysing the lyrics and listening to the phonographic material was one of the strengths of this piece. Although our analysis was not focused on the musical structure or other aspects of musicological relevance, listening to the songs added accuracy to the qualitative assessments.

Some limitations of the present work derive from the specificity of the geographical scope, the subcultural particularities of Spanish punk, and the lower representation of the female gender in rock-derived musical styles. Future comparative studies with other populations and other musical genres are warranted to overcome these issues.

Future research exploring the reception of songs with messages that associate violence, criminality and mental disorders can shed light on the implications of the exposure to such content. Similarly, they may contribute to understanding how those messages promote or challenge the stigmatisation of people with mental health problems. Moreover, using such song lyrics to encourage thoughtful discussions is another area open to study in medical education.

Finally, it is pertinent to note that the data presented do not allow inferring the effect of these contents on the audiences, nor the opinions, behaviours, or personal dispositions of the authors, since the last work as a sort of “spokesperson” of the social representations of their socio-cultural context in a specific historical period.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.