Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in young people from urban neighbourhoods in Latin America (OLA)

Más datosYoung people in South America's deprived urban regions are at heightened risk for mental disorders. High social media engagement (SME) – the intensity of use and emotional connection to social platforms – is associated with depression and anxiety, but its role in symptom persistence or recovery remains unclear.

ObjectiveTo assess if SME changes in young people from deprived urban areas of South America with depression/anxiety link to improvement of symptoms or quality of life (QoL).

MethodsA longitudinal study assessed 1280 participants with depression and/or anxiety at baseline. We used the Multidimensional Facebook Intensity Scale (MFIS, SME), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8, depression), General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7, anxiety), and Manchester Short Assessment (MANSA, QoL). At 12- and 24-month follow-ups, 1255 and 1013 participants were analyzed. Analyses included descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations, ANOVA, and Games–Howell post hoc tests.

FindingsHigher SME levels were associated with higher depression/anxiety scores at all time points. Participants who reduced or maintained stable SME showed significantly greater improvements in depression and QoL compared to those who increased SME.

ConclusionsReducing SME or fostering healthier engagement may be clinically relevant to reduce depression and anxiety risk and improve QoL. Future research should explore intervention efficacy.

Los jóvenes de áreas urbanas desfavorecidas de Sudamérica presentan un alto riesgo de desarrollar trastornos de salud mental. El alto compromiso con las redes sociales (CRS) —la intensidad y el compromiso emocional con su uso— se asoció con depresión y ansiedad anteriormente, pero su impacto en la persistencia o recuperación de síntomas es incierto.

ObjetivoEvaluar si los cambios en el CRS en jóvenes de áreas urbanas desfavorecidas con depresión/ansiedad se relacionan con la mejora de síntomas o de la calidad de vida (CV).

MétodosEstudio longitudinal con 1.280 participantes con depresión y/o ansiedad. Se usaron las escalas Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8, depresión), General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7, ansiedad), Manchester Short Assessment (MANSA, CV) y Multidimensional Facebook Intensity Scale (MFIS, CRS). En los seguimientos a 12 y 24 meses se analizaron 1.255 y 1.013 participantes. Los análisis incluyeron estadísticas descriptivas, correlaciones de Pearson, ANOVA y pruebas post hoc de Games-Howell.

ResultadosNiveles más altos de CRS se asociaron con mayores puntajes de depresión/ansiedad en todos los puntos de evaluación. Reducir o mantener estable el CRS se asoció a mejoras significativamente mayores en depresión y CV en comparación con aumentar el CRS.

ConclusionesReducir el CRS o fomentar un uso saludable puede ser clínicamente relevante para reducir el riesgo de depresión y ansiedad, y para mejorar la CV. Se deben investigar intervenciones efectivas.

The relationship between social media use, internet consumption, depression, and anxiety has been a focus of attention in recent years for research and information/communication media. A large proportion of young people spend significant time on their smartphones, the internet, and social media, which has been associated with sleep disturbances and emotional difficulties.1–3 Studies indicate that heavy use of smartphones and social media among young people is correlated with increased rates of mental health issues, such as mental distress, self-harm, body image concerns, and suicidal tendencies.1–5 Additionally, meta-analyses have demonstrated significant statistical associations between problematic social media use and heightened levels of depression, anxiety, and stress.6 A meta-analysis from 20227 identified a linear dose-response relationship between time spent on social media and mental distress; however, this analysis focused solely on depression, with only one of the included studies conducted in South America. Furthermore, research has shown that frequent social media use is linked to a lower perceived quality of life among young individuals.5,8–10

The way young people interact with social media is complex. Despite many perceiving social media as harmful to their mental health, with some even describing it as addictive,11 it also presents potential benefits. Social media can promote positive mental health by facilitating social connections, providing access to essential health and medical information, and enabling peer support.2,12 In fact, several interventions designed to support youth mental health have utilized social media platforms effectively.13

This intricate interplay between social media use and mental health highlights the need for further investigation. Henrich et al.14 emphasize that much of the existing research in behavioral science is based on data from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies, cautioning against assuming these results are universally applicable. Also, previous research suggests that more longitudinal studies would contribute to a better understanding of the impact of social media engagement (SME) on young people's mental health.15–17 Although previous longitudinal research on this topic tends to find small or no association between SME and mental health, most of these studies18–21 use lagged or cross-lagged analyses to explore the link between SME at baseline and mental health outcomes at follow-up stages.

Alternatively, we aimed to examine whether changes in SME over one- and two-year periods are associated with changes in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and perceived quality of life (QoL) among young people who presented with depressive and/or anxious symptoms at baseline. SME was measured using an adapted version of the Multidimensional Facebook Intensity Scale (MFIS) and categorized into four levels. Participants were grouped by change trajectory (increased, decreased, or no change in SME) between baseline and follow-up. We conducted this longitudinal study in three capital cities of South America, focusing on youth from vulnerable urban areas where access to mental health care is often limited and under-researched.

MethodsStudy designThis research is part of the “OLA (Overcoming Latin America) program - Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in young people from urban areas in Latin America,” a longitudinal, multisite investigation. It uses an observational, prospective cohort design to follow adolescents and young adults over time in three South American capital cities: Bogotá (Colombia), Buenos Aires (Argentina), and Lima (Peru),22 exploring their perceived quality of life and the recovery/persistence of anxiety and/or depression. The primary objective of the OLA program is to identify the dynamic role of resources in preventing or facilitating recovery from symptoms of depression and anxiety. We examine how resource use differs between individuals with and without symptoms at baseline and which factors are associated with recovery during the follow-up period. Data were collected at baseline, with follow-ups conducted at 12 and 24 months to track changes over time. Standardized data collection procedures were employed across sites to ensure consistency, as outlined in the OLA study protocol.22

Sample and inclusion criteriaParticipants were recruited between April 2021 and November 2022 from districts classified as economically disadvantaged in each city. These areas were identified using city-specific deprivation indices: the Human Development Index (HDI)23 in Bogotá and Lima and the Unsatisfied Basic Needs Index (NBI)24 in Buenos Aires. Districts ranking in the lowest 50% on these metrics were eligible for inclusion.

Two age groups were targeted: adolescents aged 15–16 years and young adults aged 20–24 years. Eligibility criteria required participants to reside in eligible districts and provide written informed consent. For adolescents, both their assent and parental/guardian written informed consent were necessary. Consent processes were adapted to participants’ preferences, with options for in-person or online completion supported by a researcher. Exclusion criteria included severe mental illness, cognitive impairment, illiteracy, or an inability to provide informed consent.

At baseline, self-report questionnaires were used to assess study outcomes. Data was collected using paper or online forms, according to the possibilities and convenience of participants. During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, only online assessments were conducted.

A score of 10 or higher on the PHQ-8 or GAD-7 was set as the threshold to identify symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. The sample size for this study was determined based on the ability to detect predictors of recovery. Assuming that a given predictor (e.g., a personal or social resource) is present in 10% of the sample, a total of 762 participants would be needed to detect a difference in recovery rates between 40% and 60% with 90% power and a 5% significance level. To account for an anticipated 25% attrition rate over time, the required baseline sample was increased to 1016 individuals experiencing psychological distress. A minimum of 340 participants with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety were recruited in each city, a total of 1020 participants. Recruitment efforts focused on schools and community centers, using convenience sampling to suit each context.

Follow-up assessmentsParticipants with baseline scores of 10 or higher on either the PHQ-8 or GAD-7 were invited to participate in follow-up assessments at 12 and 24 months post-baseline. We conducted 12-month follow-ups from May 2022 to November 2023, and 24-month follow-ups between June 2023 and July 2024. These follow-ups aimed to assess changes in depression and anxiety symptoms, quality of life, and SME over time.

Instruments and variablesOutcome variablesAll outcome measures were assessed using standardized, validated instruments widely used in mental health research. The same Spanish-language version of each scale was used across all three countries. Validated Spanish versions were employed for the PHQ-825 and GAD-7.26 For the MANSA, we used a version translated from the original English version, previously used in Latin American populations in GLOBE study.27

Depression | Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8)The PHQ-8 is a validated, eight-item tool designed to measure symptoms of depression. Participants indicate how frequently they have experienced each symptom in the past two weeks, using a scale from “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). Its concise and straightforward format, combined with proven reliability, makes it widely utilized in clinical and research contexts for depression screening.25

The PHQ-8 total score is calculated by summing the scores of the eight items, providing a measure of depressive symptoms, with total scores ranging from 0 to 24, being a higher score equivalent to more symptoms of depression. At baseline, a score of 10 or more was considered the threshold for depression. Participants with depression were included for follow-ups and, at both follow-up stages, the increase/decrease of score was considered as a continuous variable.

Anxiety | General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)The GAD-7 is a validated, seven-item questionnaire that assesses common symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Participants rate the frequency of symptoms over the past two weeks on a scale from “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). Known for its brevity, simplicity, and reliability, it is a standard tool in both clinical practice and research.26

The GAD-7 total score represents the sum of the seven items, measuring generalized anxiety symptoms, with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 21, being a higher score equivalent to more symptoms of anxiety. At baseline, a score of 10 or more was considered the threshold for anxiety. Participants with depression were included for follow-ups and, at both follow-up stages, the increase/decrease of score was considered as a continuous variable.

Quality of life | Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA)The MANSA is a validated, self-report questionnaire that evaluates subjective QoL across various domains, including satisfaction with life overall, work or studies, finances, friendships, leisure, housing, safety, physical and mental health, sexuality, and family. Participants rate their satisfaction on a scale from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 7 (completely satisfied). The MANSA is widely recognized as a reliable instrument for assessing perceived quality of life in clinical and research settings.28

The MANSA score is calculated as the mean score across the 12 items. It provides a measure of subjective quality of life, with scores ranging from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 7 (completely satisfied).

Predictor variablesSocial media engagementAn adapted version of the MFIS scale,29 developed to assess Facebook use, was employed to measure overall SME. The term “Facebook” was replaced with “social media” to meet the objective of our study, some items were removed, and some were added. These adaptations were informed by insights from the first phase of the OLA study (Work Package 1 – WP1), which involved 18 online focus groups and 12 structured group discussions integrated into art workshops.30 Participants included adolescents, young adults, and professionals working with these age groups. Discussions focused on youth mental health and the resources they utilized, leading to the addition of items about social media interactions and seeking solutions through social media platforms. Items deemed redundant or overly similar were removed (see supplementary material for original and adapted versions).

The resulting 15-item scale asks participants to rate their agreement with various statements on a 5-point Likert scale, from “1” (Strongly Disagree) to “5” (Strongly Agree).

The total SME score, calculated by summing the responses to the 15 items, measures overall SME. The possible scores range from 15 to 75, higher scores meaning higher engagement with social media. SME was categorized into four levels: low engagement (scores 15–30), moderate engagement (31–45), high engagement (46–60), and very high engagement (61–75). These categories correspond to average responses on the SME scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), where low engagement represented average scores between 1 and 2, moderate engagement between 2 and 3, high engagement between 3 and 4, and very high engagement between 4 and 5.

Data analysisAll analyses were performed using the statistical software R Core Team, 2023.31 The data analysis was conducted in three main steps. First, descriptive statistics were used to explore changes in the mean values of each variable across the three measurement points. The mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values were calculated for each time point. Second, zero-order Pearson correlations were computed to explore relationships between the variables. This included analysing change scores derived by calculating the difference between each follow-up measurement and the baseline measurement for each variable (i.e., 12 months minus baseline; 24 months minus baseline).

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Games–Howell post hoc test were conducted to examine differences in the change of GAD-7, PHQ-8, and MANSA scores across three groups. These groups were formed based on changes in SME between baseline and 12 months, and between baseline and 24 months follow-ups: The Increased group included individuals whose SME increased enough to shift to a higher category; the no change group included those whose SME remained stable across time points; and the decreased group included individuals whose SME decreased enough to shift to a lower category.

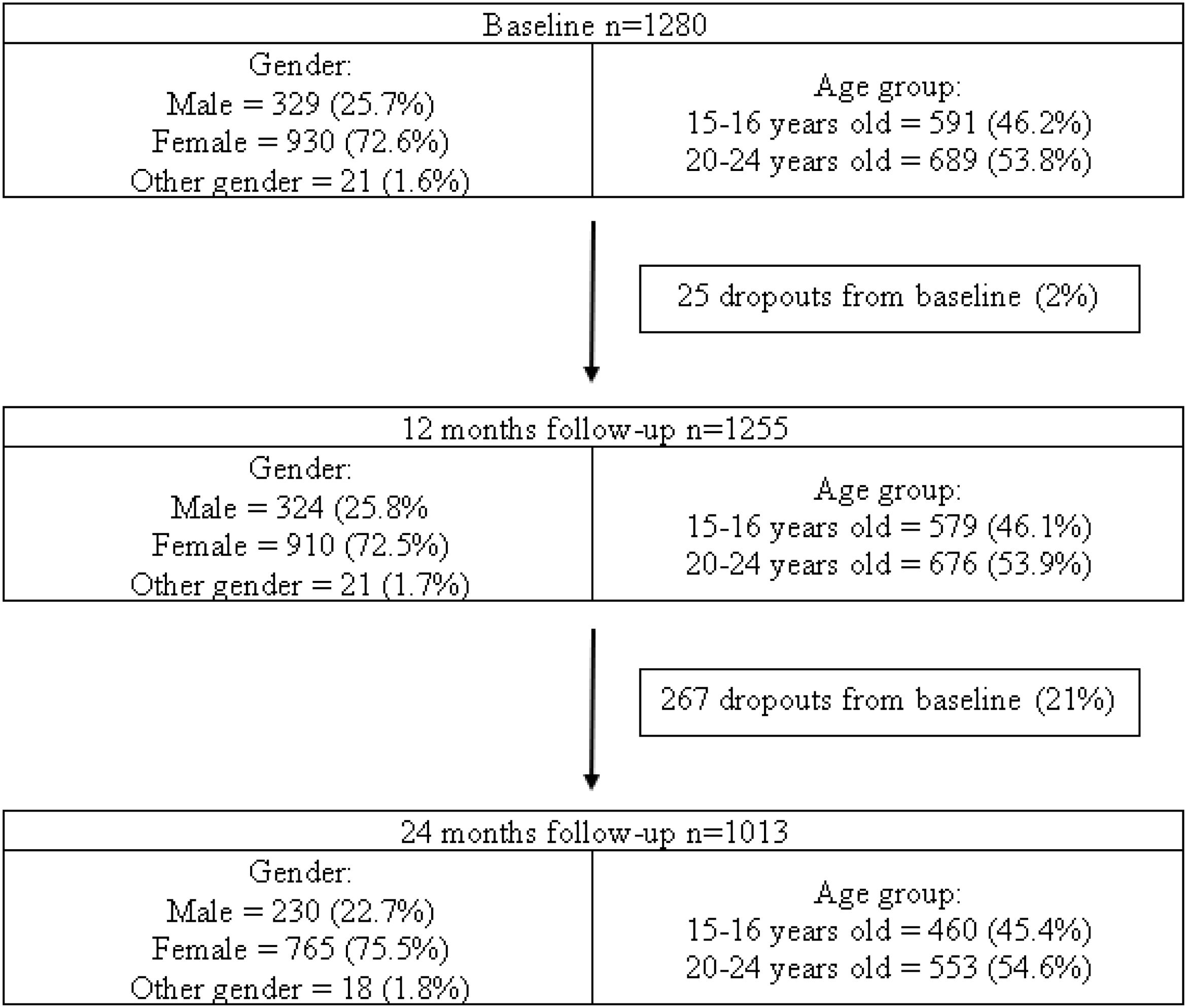

ResultsThe study included a total of 1280 participants with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety at baseline, with a slight decrease in sample size at subsequent time points (n=1255 at 12 months and n=1013 at 24 months).

Participants were classified according to age (15–16 or 20–24 years at baseline) and gender (male, female or other gender). Fig. 1 shows the distribution of participants in these groups.

SME, depression, anxiety, and quality of life over timeMean scores for each variable were calculated at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months. Table 1 shows this progression across the three time points. There were up to 7 participants with missing values reported during the analyses; this is reflected in the sample size variation in Table 1.

Mean scores and standard deviation of SME, GAD-7, PHQ-8 and MANSA at each time point.

| Baseline | 12 months | 24 months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| SME | 1273 | 43.19 | 10.39 | 1251 | 41.59 | 10.00 | 1009 | 41.56 | 10.09 |

| GAD-7 | 1279 | 11.47 | 3.99 | 1255 | 9.98 | 4.73 | 1013 | 9.62 | 4.90 |

| PHQ-8 | 1280 | 13.95 | 4.32 | 1255 | 11.61 | 5.64 | 1013 | 10.97 | 5.60 |

| MANSA | 1279 | 4.27 | 0.97 | 1253 | 4.28 | 1.03 | 1011 | 4.30 | 1.01 |

SME demonstrated a slight decline over time. Depression (PHQ-8) and anxiety (GAD-7) mean scores also showed a decrease, which was bigger in both cases between baseline and 12 months than from 12 to 24 months. In contrast, quality of life (MANSA) remained relatively stable.

Associations between SME and mental health outcomesThe cross-sectional associations of SME levels with depression, anxiety and perceived QoL scores were tested at each time point. Table 2 shows these associations at the three time points.

At baseline, SME showed a weak but significant positive correlation with depression (r=.053, p<.05). At 12 months, SME was positively associated with both anxiety (r=.073, p<.05) and depression (r=.120, p<.05). At 24 months, SME was again positively correlated with anxiety (r=.101, p<.05) and depression (r=.118, p<.05), and negatively correlated with quality of life (r=−.075, p<.05).

Association of change in SME with changes in mental health over timeTo determine the evolution of SME, QoL, and symptoms of depression and anxiety, the change in scores for all variables was calculated for each participant between baseline and 12 months, and between baseline and 24 months follow-ups. To evaluate how the change in SME relates to fluctuations in QoL and symptoms of depression and anxiety, associations between these variations in scores were tested. The correlations between SME change and the variation of depression, anxiety, and QoL scores for the same time point are displayed in Table 3.

Association of SME score variation with GAD-7, PHQ-8, and MANSA score variation at baseline to 12 months and baseline to 24 months.

Changes in SME over time were associated with the change in mental health outcomes. Increases in SME from baseline to 12 months were significantly associated with increases in depression (r=.092, p<.05) and decreases in QoL (r=−.090, p<.05). From baseline to 24 months, SME increases were significantly correlated with increases in anxiety (r=.095, p<.05) and depression (r=.146, p<.05), although the correlation with QoL was not statistically significant.

Group-level analysis of SME changesParticipants were categorized based on SME change trajectories: increased, no change, or decreased, according to change in their SME categorization as explained under the “data analysis” subtitle. These groups were compared to determine whether there are differences in how their depression, anxiety, or QoL scores evolved. The mean change in scores for each variable and the results of the ANOVA and Games–Howell post hoc tests are presented in Table 4 for baseline to 12 months, and baseline to 24 months follow-up.

Mean change in scores, ANOVA and pairwise comparisons of SME change groups according to change in depression, anxiety, and QoL between baseline and 12 months, and between baseline and 24 months follow-up.

| Change between baseline and 12 months follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SME | Decreased | No change | Increased | F score | Sig |

| Depressiona(n=1243) | −2.95(n=315) | −2.45(n=684) | −1.14(n=244) | 7.82 | <0.001* |

| Anxietyb(n=1243) | −1.69(n=315) | −1.50(n=684) | −1.16(n=244) | 0.78 | 0.46 |

| Quality of lifec(n=1240) | 0.17(n=315) | 0.02(n=681) | −0.17(n=244) | 6.49 | <0.01* |

| Change between baseline and 24 months follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SME | Decreased | No change | Increased | F score | Sig |

| Depressiond(n=1003) | −3.84(n=256) | −3.19(n=563) | −1.05(n=194) | 12.89 | <0.001* |

| Anxietye(n=1003) | −2.20(n=256) | −1.90(n=563) | −0.99(n=194) | 3.66 | <0.05* |

| Quality of lifef(n=1001) | 0.14(n=256) | 0.09(n=551) | −0.24(n=194) | 11.63 | <0.001* |

Games–Howell test showed a significant difference between the decreased and increased groups, and between the no change and increased groups (both p<0.01). For details, see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material.

Games–Howell test failed to show statistically significant differences between groups. For details, see Fig. S2 in the supplementary material.

Games–Howell test showed a significant difference between the decreased and increased groups (p<0.01). For details see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material.

Games–Howell test showed a significant difference between the decreased and increased groups, and between the no change and increased groups (both p<0.001). For details, see Fig. S4 in the supplementary material.e Games–Howell test failed to show statistically significant differences between groups. For details, see Fig. S5 in the supplementary material.

Games–Howell test showed a significant difference between the decreased and increased groups, and between the no change and increased groups (both p<0.001). For details, see Fig. S6 in the supplementary material.

ANOVA results showed a significant group effect for depression (F=7.82, p<.001) and QoL (F=6.49, p<.01) at 12 months. Participants in the decreased SME group experienced the greatest reductions in depression and improvements in QoL scores, while the increased SME group was the only one to show lower levels of QoL than at baseline.

Post hoc analyses at this time point revealed that participants in the decreased group show a statistically significant difference in depression and QoL scores compared with the increased SME group (p<.01). For QoL, the difference was significant between the decreased and increased SME groups (p<.01). Participants who reduced their SME from baseline to 12 months follow-up, showed an improvement in QoL, while those who increased SME presented a deterioration in QoL. Reducing SME was also linked to a 159% greater improvement in depression than increasing SME (−2.95 vs. −1.14 PHQ-8 score). Maintaining stable SME over the same period was associated with a 115% greater improvement in depression compared to increasing SME (p<.01) (−2.45 vs. −1.14 PHQ-8 score).

At 24 months, ANOVA indicated significant differences across SME change groups for depression (F=12.89, p<.001), QoL (F=11.63, p<.001), and anxiety (F=3.66, p<.05).

Post hoc tests also showed that both the decreased and the no change SME groups exhibited statistically significant greater reductions in depression (both p<.001) and improvements in QoL (both p<.001) than the increased SME group. Differences in anxiety were not statistically significant in the post hoc comparisons. In this case, reducing SME was linked to a 266% greater improvement in depression symptoms compared to increasing SME (−3.84 vs. −1.05 PHQ-8 scores), while stable SME was associated with a 204% greater improvement (−3.19 vs. −1.05 PHQ-8 scores). At this time point, both reduced and stable SME were associated with improved QoL, whereas increased SME corresponded to diminished QoL (+0.14, +0.09, and -0.24, respectively).

Subgroup analyses: gender and ageThe results showed consistent associations between increases in SME and poorer mental health outcomes across gender and age groups. For both males and females, higher SME over time correlated with increased scores of depression and anxiety and decreased scores of quality of life at 12 and 24 months. Similarly, age-specific analyses revealed comparable patterns, with both adolescents and young adults exhibiting higher depression and anxiety scores, along with lower quality of life, associated with increases in SME. See Tables S1 and S2 in the supplementary material for details on these results and correlations for each gender and age group, respectively.

DiscussionOur findings suggest that young people from deprived urban areas in South America who experience depression and/or anxiety are more likely to have worse mental health outcomes if they also exhibit high levels of SME. Over the 24-month period, increased SME levels were consistently associated with more severe symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as diminished perceived quality of life (QoL). Moreover, participants who increased their SME over time showed a significantly lower probability of recovering from depression and of improving subjective QoL than those who reduced or maintained stable SME.

Although our study's observational design does not allow for causal relationships to be established, these findings suggest that reducing or maintaining stable SME levels may yield long-term benefits in mitigating depressive symptoms and enhancing QoL perception. A previous longitudinal study32 found that a 1.7-point difference in PHQ-9 and a 1.5-point difference in GAD-7 scores are sufficient for patients with symptoms to experience noticeable improvement. This difference in depression scores can be found between the reduced and increased SME groups at 12 months. By 24 months, even the stable SME group reaches this difference compared to the increased SME group.

Participant retention in our cohort was satisfactory. Of the 1280 participants assessed at baseline, 1255 (98%) completed the 12-month follow-up, and 1013 (79%) completed the 24-month follow-up. This corresponds to attrition rates of 2% and 21%, respectively. These rates are satisfactory given the two-year duration of the study and the challenges of retaining adolescents and young adults in longitudinal mental health research, particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged urban settings.

Strengths and limitationsStrengthsBy focusing on economically disadvantaged urban areas in three South American capitals, this study addresses a research gap in a culturally and socioeconomically diverse population with limited access to mental health resources. Furthermore, we only included young people with baseline symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, while most samples in SME research are composed of the general population. The use of validated tools (PHQ-8, GAD-7, MANSA) ensures reliable assessment of depression, anxiety, and QoL. Finally, the study achieved a satisfactory retention rate, particularly given the known challenges of conducting longitudinal research in socioeconomically vulnerable urban contexts.

LimitationsFirstly, while the longitudinal approach strengthens associations, causality cannot be established due to the study's observational design. Secondly, reliance on self-report measures may introduce biases, such as underreporting or overreporting symptoms and behaviors. Also, the adapted SME scale does not distinguish between active and passive engagement or platform-specific behaviors, which may impact mental health differently. Thirdly, while focusing on South American cities is a strength, findings may not generalize to other regions or populations with differing social media use patterns and cultural dynamics. Lastly, other confounding variables were not considered in the analysis.

Comparison with previous literatureOur findings are consistent with previous research suggesting an association between social media engagement (SME) and mental health outcomes in young people, in this case focusing on those with symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. Prior studies have identified a significant link between high levels of social media use and increased rates of depression, anxiety, and mental distress in adolescents and young adults.1–5 A multivariable analysis was also conducted over the full baseline dataset of this study,33 which shows the association of elevated SME with symptoms of depression and anxiety as well. Our study supports those conclusions, showing that, among people with depression and/or anxiety, elevated SME is associated with more severe symptoms and a diminished perception of QoL. These results are also in line with previous meta-analyses that have highlighted the negative impact of excessive social media use on mental health.6–7

Most previous longitudinal research on this topic assessed the impact of SME at baseline on mental health outcomes at follow-up, using lagged or cross-lagged analyses.18–21 These studies tend to find either small or no associations between variables. In contrast, we analyzed the change in SME from baseline to follow-ups and its association with the change in mental health outcomes during the same period, finding noteworthy patterns. In our study, reducing SME from baseline to 12 and 24 months was similarly linked to significantly better improvement of depression and anxiety symptoms, and perceived QoL, compared to those who increased SME. These findings underscore the potential benefits of reducing SME for young people experiencing mental health challenges.

Previous studies have shown the potential benefits of reducing screen time and limiting social media use as a means of mitigating mental health issues.2,5,13 Our study provides a deeper insight into this by suggesting that, when it comes to a longitudinal approach, the worst outcome corresponds to people who increase their SME. This draws attention not only to the level of SME, but also to its progression through time. Especially for patients with depression, reducing or maintaining stable SME can lead to significant improvements in depression symptoms, while increasing SME is associated with increased depression symptoms and diminished QoL.

Previous research has also presented some potentially positive aspects of SME.12,13,30,34 We acknowledge the complex nature of the relationship between SME and youth mental health. Our findings show a linear pattern for depression, anxiety and QoL scores among the SME change groups at 12 and 24 months (Table 4); i.e., reducing SME in people with depression and/or anxiety was associated with better mental health outcomes than maintaining stable SME. Maintaining stable SME, meanwhile, correlated to an even greater extent with better outcomes than increasing SME. Most participants in our sample kept a stable SME both at 12 and 24 months, and yet reached significantly better improvements in depression at 12 and 24 months and in QoL at 24 months than those who increased SME. Huang et al.35 argue that, when it comes to SME, not everything is about screen time. Other factors such as social interaction, and passive or active use, affect the way SME is related to mental health. While our findings stress the risk that increasing SME seems to present, exploring the nuances of this interplay in future research may be relevant.

ImplicationsPolicy implicationsPublic debates on the necessity of regulating smartphone and internet use for adolescents are occurring worldwide.36–38 Our findings highlight the importance of developing and testing public health policies aimed at mitigating the potential harms of excessive SME among vulnerable populations. Educational campaigns targeting youth, caregivers, and educators could emphasize healthy social media habits and provide strategies for balanced engagement. Policymakers may also consider advocating for regulations that encourage platforms to adopt features that support responsible usage, such as screen time reminders or content moderation tools. Our findings contribute to the ongoing global conversation on adolescent well-being, reinforcing the urgency of implementing evidence-based strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of increasing SME on mental health.

Clinical relevanceThe observed reductions in PHQ-8 scores among participants who decreased or stabilized their SME levels hold significant clinical importance. According to Kounali et al.,32 a reduction of approximately 1.7 points on the PHQ-9 scales is associated with a meaningful improvement in perceived well-being for individuals experiencing symptoms of depression. In this study, the difference in improvement between people who increased SME and those who did not exceeded that score. Although causality cannot be established, exploring SME and suggesting reducing it may be an accessible intervention to alleviate symptoms of depression, especially in populations with limited access to formal mental health care. These results underscore the importance of integrating discussions about social media use into clinical practice, particularly for patients who exhibit elevated SME or who increase SME compared to a previous period. Clinicians may also benefit from developing targeted psychoeducation programs that raise awareness about the potential impact of increasing SME on mental health and offer practical guidance for healthy digital habits.

Future researchFuture research should aim to explore the causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between SME and mental health outcomes. Longitudinal studies with more granular assessments of SME—such as distinguishing between active and passive use or analysing the role of social support within online interactions—could provide valuable insights. Additionally, research on the cultural and socioeconomic factors influencing SME in different regions could help tailor interventions to the unique needs of various populations, ensuring their effectiveness and accessibility. Future research needs to develop and test strategies to reduce SME, as mere prohibitions of social media may be challenging to implement or even not feasible. Our study assessed individuals who spontaneously changed their levels of SME. If effective interventions to reduce SME are identified, experimental studies are needed to confirm if the reduction of SME with these interventions leads to improved mental health.

ConclusionsOur study provides evidence of a significant relationship between SME and mental health outcomes among young people with depression and/or anxiety in deprived urban areas of South America. Over a 24-month period, increased SME was consistently associated with worse mental health outcomes, including heightened symptoms of depression and anxiety and diminished QoL. In contrast, reducing or maintaining stable SME levels corresponded to substantial improvements in these measures, underscoring the potential benefits of managing SME in this population.

While causality cannot be established, these findings highlight the importance of addressing SME as a potentially modifiable factor in mitigating mental health challenges. The dose-response relationship observed—where reduced or stable SME yielded better outcomes compared to increased SME—further supports this perspective.

Given the complex interplay between SME and mental health, interventions that encourage reduced SME or promote healthier engagement patterns may offer a pragmatic approach to enhancing well-being. Future studies should continue to explore the mechanisms underlying these associations and the efficacy of such interventions in diverse contexts.

Ultimately, our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence on the impact of digital behaviors on youth mental health, emphasizing the need for clinical, policy, and research efforts to address the risks associated with increasing SME.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of Universidad de Buenos Aires (dated October 2nd, 2020), Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (November 20th, 2020 – ref. FM-CIE-1138-20), Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (November 16th, 2020 – ref. Constancia 581-33-20) and the Research Ethics Committee of Queen Mary, University of London (November 16th, 2020 – ref. QMERC2020/02) approved the study protocol. All procedures conducted as part of this study comply with the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki and with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees.

FundingThis work was supported by the Medical Research Council [grant number MR/S03580X/1].

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Natividad Olivar, Liliana Hidalgo-Padilla, and Karen Ariza-Salazar for their work as project coordinators and their involvement in participant recruitment and data collection. We are also grateful to Sandra Milena Cañón Gonzalez, María Camila Roldán Bernal, Heidy Sanchez, Noelia Cusihuaman-Lope, and Jenny Bejarano for collaborating on follow-up recruitment and data collection. Additionally, we thank Jimena Rivas and Daniela Ramirez-Meneses for their contributions to baseline participant recruitment and data collection. We are also thankful to Ángela Flórez-Varela, Laura Cruz Marin, María Paula Jassir Acosta, Sofia Madero, and Fernando Esnal, who took part in both baseline and follow-up recruitment and data collection.

We would like to extend our gratitude to Nelcy Rodríguez Malagón and David Niño-Torres for their work during the data cleaning process, and to Ezequiel Flores Kanter for his support with the statistical analyses of the present paper.

Lastly, the authors express their gratitude to all the participants for generously sharing their data, experiences, and perspectives with us.