Building resilience and resources to reduce depression and anxiety in young people from urban neighbourhoods in Latin America (OLA)

Más datosExplore the association between being a victim of bullying and the presence of symptoms of depression and anxiety, and evaluate if participants’ resilience and structural and cognitive social capital are effect modifiers.

MethodsIn this case–control study, participants were adolescents and young adults from disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Bogotá, Buenos Aires, and Lima. We conducted logistic regressions to address the association between bullying and the presence of symptoms of depression (PHQ-8) and anxiety (GAD-7). We stratified the analysis by resilience (CD-RISC 10), cognitive social capital, and structural social capital (SASCAT) levels and obtained the predicted probabilities of having symptoms.

ResultsYoung people who were bullied more than a year ago had 2.39 and 2.06 times higher odds of having symptoms of depression and anxiety, respectively, compared to participants who were never bullied. Those bullied in the last year had 3.58 and 4.01 times higher odds of having symptoms of depression and anxiety, respectively, compared to young people who were never bullied. Having high levels of resilience and cognitive social capital reduced the probability of having symptoms of depression and anxiety, but structural social capital did not.

ConclusionsBullying was linked to depression and anxiety in disadvantaged Latin American youth. Interventions should focus on preventing bullying and enhancing resilience and community resources to support mental well-being.

Explorar la asociación entre ser víctima de bullying y la presencia de síntomas de depresión y ansiedad, y evaluar si la resiliencia y el capital social estructural y cognitivo son modificadores del efecto.

MétodosEn este estudio de casos y controles participaron adolescentes y adultos jóvenes de barrios desfavorecidos de Bogotá, Buenos Aires y Lima. Se usaron regresiones logísticas para analizar la asociación entre el bullying y la presencia de síntomas de depresión (PHQ-8) y ansiedad (GAD-7). El análisis se estratificó por niveles de resiliencia (CD-RISC 10), capital social cognitivo y estructural (SASCAT), y se obtuvo las probabilidades predichas de tener síntomas.

ResultadosLos jóvenes que sufrieron bullying hace más de un año tuvieron 2.39 y 2.06 veces más chances de presentar síntomas de depresión y ansiedad, respectivamente, a comparación de los que nunca fueron víctimas. Las víctimas de bullying en el último año tuvieron 3.58 y 4.01 veces más chances de presentar síntomas de depresión y ansiedad, respectivamente, a comparación de los que nunca fueron víctimas. Tener altos niveles de resiliencia y capital social cognitivo se asoció con una menor probabilidad de tener síntomas de depresión y ansiedad, pero el capital social estructural no tuvo el mismo efecto.

ConclusionesEl bullying se asoció con síntomas de depresión y ansiedad en jóvenes desfavorecidos de América Latina. Las intervenciones deben centrarse en prevenir el bullying y fortalecer la resiliencia y los recursos comunitarios para promover el bienestar emocional.

Bullying is defined as a form of intentional and aggressive abuse that extends over a prolonged period and targets a relatively powerless person.1,2 One or more people can exert the abuse, and it can be physical (e.g., kick, punch, push, steal, destroy property), social (e.g., ignore, exclude, spread rumours), verbal (e.g., insult, humiliate, threaten), sexual (e.g., sexual harassment, inappropriate touching), or cybernetic (e.g., violent text messages, posting embarrassing photos or videos).3–5 Two out of six students aged 12–13 from fifteen Latin American and Caribbean countries were victims of bullying.6

Cyberbullying has gained attention due to the COVID-19 pandemic, when the use of social media significantly increased.7 Unlike bullying, cyberbullying does not limit itself to a particular space (e.g., school) but can occur at any time through different online platforms (e.g., Instagram, X, TikTok, WhatsApp, etc.).8 Moreover, perpetrators can remain anonymous, making it harder for them to take accountability.

Previous studies have linked both being a victim of bullying and cyberbullying to feelings of loneliness, stress, depression, anxiety, and substance use.1,8–10 Additionally, these victims exhibit problems concentrating, lack of motivation, and poor academic performance.8 Suicidal thoughts and self-harm are also outcomes of bullying and cyberbullying.10

Bullying victimisation can also have a long-term impact. Childhood bullying victimisation is associated with increased mental health service use in childhood, adolescence, and early and mid-adulthood.11,12 Prior work also suggests that recent and chronic experiences of bullying have larger associations with mental health problems.11,13

However, resilience theory suggests that young people with resilience resources or assets can withstand adversity with minimal or no distress.14,15 Resilience assets are individual factors (e.g., competence, problem-focused coping, and cognitive restructuring), and resilience resources are external factors that promote healthy development (e.g., family and community support).15 Instead of understanding resilience as only an individual and stable trait, this view also considers social and community resilience.14,16 External resources can provide a positive environment for individuals to develop positive assets that protect them against the detrimental effects of stressful life events.14,17,18

There is evidence that resilience works as a protective factor for children and adolescents against developing mental distress in the face of being a victim of bullying.19–21 Most of these studies took place in Asia, and while some used resilience scales that consider social resources from the adolescent's environment, as well as individual assets,19–21 some just focused on trait resilience.22,23 Moreover, these researchers have mainly studied bullying among adolescents and children, overlooking young adults who also attend educational settings.

Social capital is defined as the structure and quality of social relationships from which individuals, social groups, and society may benefit,24 and is considered a resilience resource.25 Social capital has two dimensions: structural and cognitive. Structural social capital comprises relationships, networks, associations, and institutional structures that link people and groups, whereas cognitive social capital consists of belonging, trust, reciprocity, altruism, and community responsibility.25,26

Social capital has been inversely associated with common mental health disorders18,27 but, to our knowledge, no previous study has explored the protective characteristics of structural and cognitive social capital against bullying's detrimental effects on young people's mental health.

Evidence shows that rates of bullying tend to be higher in countries with greater social inequality.28 Latin America is one of the most unequal regions worldwide29 and is therefore a critical setting for studying the psychological consequences of bullying. Focusing on adolescents and young adults from deprived urban neighborhoods allows us to capture experiences from groups who may be both more exposed to bullying, more vulnerable to its mental health effects, and underrepresented in scientific research.

In this paper, we aim to explore the association between being a victim of bullying and the presence of symptoms of depression and anxiety among adolescents and young adults from low-income communities in Latin America and to evaluate if participants’ individual resilience and structural and cognitive social capital are effect modifiers.

Considering the literature previously exposed, we propose that bullying increases the risk of symptoms of depression and anxiety, and individual resilience and social capital (structural and cognitive) weaken the association between bullying and symptoms of depression and anxiety. The strength of these buffering effects is expected to vary if the bullying victimisation occurred more than a year ago, or in the last year.

MethodsDesign and settingThis case–control study for symptoms of depression and anxiety was conducted between April 2021 and November 2022 in three Latin American capital cities: Bogotá (Colombia), Buenos Aires (Argentina), and Lima (Peru). These three cities are urbanised mainly, have a high proportion of young people, and are characterised by high rates of criminality and inequality.

We use data from the baseline assessment of a cohort study from the OLA Programme.30 One of the OLA Programme aims is to identify which characteristics, resources, and activities prevent young people from urban environments from developing depression and anxiety.

ParticipantsThe participants were adolescents (15–16 years old) and young adults (20–24 years old) who could give informed consent or assent and lived in deprived neighbourhoods in Bogotá, Buenos Aires, and Lima. We used the following criteria to consider a neighbourhood as deprived: being one of the city's poorest 50% neighbourhoods according to the United Nations Development Programme's Human Development Index31 in Bogotá and Lima, and the Unsatisfied Basic Needs Index32 in Buenos Aires.

We excluded young people who had a severe mental illness, cognitive impairment, or illiteracy. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were checked during the screening stage.

The sampling method was non-randomised. Each city had different recruitment processes, considering the restrictions due to COVID-19 and the pragmatic options for each local team.33 We recruited participants from educational institutions, community settings, and through social media. Non-governmental organisations and government education and employment programs also facilitated contact with potential participants.

The OLA cohort study aimed to recruit 2040 participants across the three cities. The goal was to include 340 participants in each city, totalling 1020, who were cases of symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, and another 340 per city who were not cases (see “Variables and instruments” section). The rationale for this sample size has been described elsewhere.30

ProceduresAfter obtaining informed assent and/or consent, we screened young people to see if they met the inclusion criteria. If they did, we invited them to complete a questionnaire either online or on paper under the supervision of a research assistant. The assessments were conducted individually or in groups, typically taking 30–60min to complete the questionnaire. For online questionnaires, we used REDCap software to record the answers.34,35 If the questionnaire was filled out on paper, a trained research assistant manually entered the data into REDCap.

Variables and instrumentsDependent variablesTo address depressive symptoms, we used the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8).36 This measure has eight items and evaluates the presence of depression symptoms in the last two weeks. The items cover eight out of the nine symptoms used in the DSM-IV to diagnose depressive disorders37; the PHQ-8 excludes the ninth symptom, which explores suicidal ideation. Each item is scored on a scale of 0 (no day) to 3 (almost every day); the total score is the sum of all the items’ scores.

We assessed anxiety symptoms using the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7).38 This seven-item questionnaire is designed to assess the presence of anxiety symptoms over the past two weeks. Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (no day) to 3 (almost every day), and the total score is the sum of all item scores.

A score higher than or equal to 10 on PHQ-8 or GAD-7 scales indicates moderate to severe symptoms of depression and anxiety,36,38 and we used this cut-off value to establish cases and controls for symptoms of depression and/or anxiety.

Latin American studies have found good psychometric properties for PHQ-839,40 and GAD-7.41–43 Moreover, for this sample, both measures presented a good fit for the one-dimensional model, divergent validity with quality of life (r=−.52 for PHQ-8 and r=−.46 for GAD-7), internal consistency (α=.86 for PHQ-8 and α=.85 for GAD-7), and measurement invariance across the three cities, age groups, genders, occupations, and education levels.

Independent variablesTo identify if a participant was a bullying victim, we used an item from an adaptation44 of the Adolescent Appropriate Life Events Scale.45 This measure includes 30 stressful life events that young people can experience. Participants reported whether they experienced each stressful life event in the last year, more than a year ago, or never. We used the stressful life event: ‘You have been a victim of physical or psychological bullying in person or virtually’. We could not run the analysis with participants who reported being bullied both in the last year and more than a year ago, because they were a small number. Instead of excluding these participants, we included them in the group of participants who reported suffering bullying in the last year. Therefore, we had three groups of participants: those who never experienced bullying, those who did more than a year ago, and those who did in the last year.

Effect modifiersResilience was assessed through the Connor-Davidson Brief Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10)46,47; translated into Spanish.48 This unidimensional scale has 10 items and a Likert scale of five points (1=never, and 5=always). The total score is the sum of all items and ranges from 0 to 40. Since there was no standardised method of categorising the scores in the literature, we divided them into tertiles: 0–21 indicating low resilience, 22–27 moderate resilience, and 28–40 high resilience. Previous articles have found evidence of the scale's validity and reliability in Latin American samples.49–51

The Short Adapted Social Capital Assessment Tool (SASCAT18) measures cognitive and structural social capital. Cognitive social capital includes four dichotomous questions (0=no, 1=yes) about trust, relationship quality, belonging, and safety in the neighbourhood. The authors18 consider a low cognitive social capital if participants answer yes to less than two of the four questions, and high cognitive social capital if they answer yes to more than two questions.

Structural social capital is assessed through three dimensions: group membership (10 questions), support from individuals and groups (21 questions), and citizenship activities (2 questions). In each dimension, the participants receive a score between 0 and 2, where 0 means no memberships to groups, no support sources, or no engagement in citizenship activities; 1 means membership to a group, a source of support, and engagement in one citizenship activity; and 2 means belonging to at least two groups, having at least two sources of support, and engagement in two citizenship activities. After adding the score of each dimension, the total score for structural social capital ranges from 0 to 6. We divided the scores into two levels according to the median: low structural social capital (0–2) and high structural social capital.3–6

Confounding variablesWe selected the following confounding variables: city (Bogotá, Buenos Aires, Lima), gender (male, female, other), age group (adolescent, young adult), main occupation (work, study, housewife, no occupation), and education degree achieved (no formal education, primary, secondary, higher education). These variables have been theoretically or empirically associated with both bullying victimisation and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Data analysisWe conducted all the analyses in STATA 18.0.52 Firstly, we deleted observations with missing values in the variables of interest. Then, we calculated the frequency of symptoms of depression (PHQ-8 score higher or equal to 10) and anxiety (GAD-7 score higher or equal to 10) for each variable.

We estimated crude and adjusted logistic regression models with bullying victimization as the independent variable and symptoms of depression and anxiety as dependent variables. All adjusted models controlled for city, gender, age group, main occupation, and education degree. Since we hypothesized that individual resilience, cognitive social capital, and structural social capital modified the association between bullying and symptoms of depression and anxiety, we stratified logistic regression models by each moderator's levels. We applied a Wald test to test a linear trend in ORs across resilience and social capital categories. Additionally, for each association modification model, we used predictive margins to visualize the estimated probabilities of depression or anxiety across bullying categories and moderator levels.

We report odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), estimated using robust standard errors. For each logistic regression model, we tested the linearity of the logit and assessed multicollinearity by the variance inflation factors (VIF).

Ethics considerationsThe study protocol and instruments were approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of Universidad de Buenos Aires in Argentina (dated October 2nd, 2020), Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Colombia (ref. FM-CIE-1138-20), Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Peru (ref. Constancia 581-33-20), and Queen Mary University of London in the UK (ref. QMERC2020/02).

All young adults provided informed consent. We required informed consent from adolescents’ parents or legal guardians and assent from the adolescents. Consent and assent could be given physically, digitally through REDCap or a photo from the signed document, or verbally via phone call or virtual meeting, which was audio recorded.

If participants had a PHQ-8 score higher than 20 or a GAD-7 score higher than 15, indicating severe symptom levels, we provided information about free or affordable mental health services. Research assistants were also prepared to address violence cases reported by the participants.

ResultsParticipants characterisationWe collected data from 2402 participants. However, 83 participants had missing data for at least one variable, so we only analysed information from 2319 participants. In this sample, 38.2% of participants were bullying victims more than a year ago, and 6.7% were bullying victims in the last year.

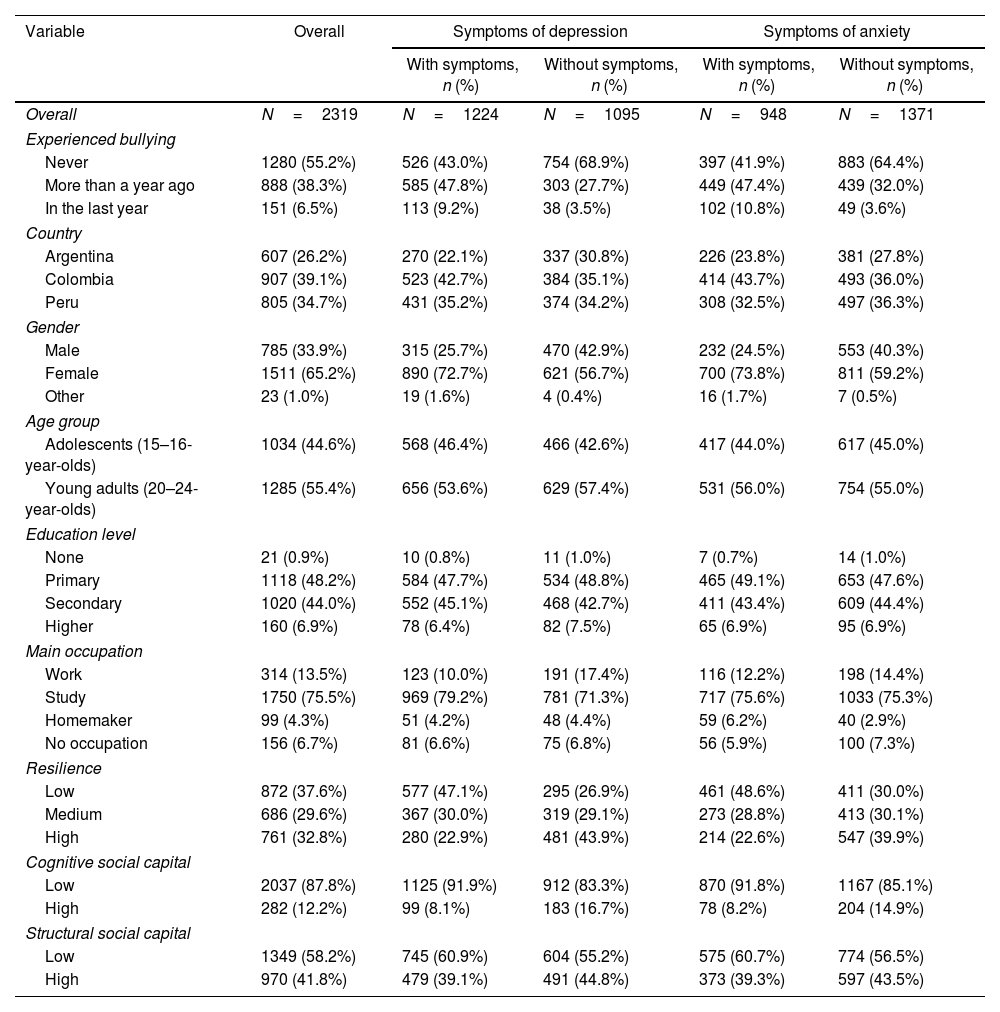

52.8% of participants had symptoms of depression (PHQ-8 score higher or equal to 10), and 40.7% had symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7 score higher or equal to 10). Table 1 shows the proportion of symptoms of depression and anxiety by participants’ characteristics. The proportion of young people with symptoms of anxiety was higher among those who were bullied in the last year, who did not identify as male or female, and who had a low resilience and cognitive social capital score. We report differences in having symptoms of depression and anxiety across subgroups in Supplementary Material.

Sociodemographic characteristics by symptoms of depression and anxiety.

| Variable | Overall | Symptoms of depression | Symptoms of anxiety | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With symptoms, n (%) | Without symptoms, n (%) | With symptoms, n (%) | Without symptoms, n (%) | ||

| Overall | N=2319 | N=1224 | N=1095 | N=948 | N=1371 |

| Experienced bullying | |||||

| Never | 1280 (55.2%) | 526 (43.0%) | 754 (68.9%) | 397 (41.9%) | 883 (64.4%) |

| More than a year ago | 888 (38.3%) | 585 (47.8%) | 303 (27.7%) | 449 (47.4%) | 439 (32.0%) |

| In the last year | 151 (6.5%) | 113 (9.2%) | 38 (3.5%) | 102 (10.8%) | 49 (3.6%) |

| Country | |||||

| Argentina | 607 (26.2%) | 270 (22.1%) | 337 (30.8%) | 226 (23.8%) | 381 (27.8%) |

| Colombia | 907 (39.1%) | 523 (42.7%) | 384 (35.1%) | 414 (43.7%) | 493 (36.0%) |

| Peru | 805 (34.7%) | 431 (35.2%) | 374 (34.2%) | 308 (32.5%) | 497 (36.3%) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 785 (33.9%) | 315 (25.7%) | 470 (42.9%) | 232 (24.5%) | 553 (40.3%) |

| Female | 1511 (65.2%) | 890 (72.7%) | 621 (56.7%) | 700 (73.8%) | 811 (59.2%) |

| Other | 23 (1.0%) | 19 (1.6%) | 4 (0.4%) | 16 (1.7%) | 7 (0.5%) |

| Age group | |||||

| Adolescents (15–16-year-olds) | 1034 (44.6%) | 568 (46.4%) | 466 (42.6%) | 417 (44.0%) | 617 (45.0%) |

| Young adults (20–24-year-olds) | 1285 (55.4%) | 656 (53.6%) | 629 (57.4%) | 531 (56.0%) | 754 (55.0%) |

| Education level | |||||

| None | 21 (0.9%) | 10 (0.8%) | 11 (1.0%) | 7 (0.7%) | 14 (1.0%) |

| Primary | 1118 (48.2%) | 584 (47.7%) | 534 (48.8%) | 465 (49.1%) | 653 (47.6%) |

| Secondary | 1020 (44.0%) | 552 (45.1%) | 468 (42.7%) | 411 (43.4%) | 609 (44.4%) |

| Higher | 160 (6.9%) | 78 (6.4%) | 82 (7.5%) | 65 (6.9%) | 95 (6.9%) |

| Main occupation | |||||

| Work | 314 (13.5%) | 123 (10.0%) | 191 (17.4%) | 116 (12.2%) | 198 (14.4%) |

| Study | 1750 (75.5%) | 969 (79.2%) | 781 (71.3%) | 717 (75.6%) | 1033 (75.3%) |

| Homemaker | 99 (4.3%) | 51 (4.2%) | 48 (4.4%) | 59 (6.2%) | 40 (2.9%) |

| No occupation | 156 (6.7%) | 81 (6.6%) | 75 (6.8%) | 56 (5.9%) | 100 (7.3%) |

| Resilience | |||||

| Low | 872 (37.6%) | 577 (47.1%) | 295 (26.9%) | 461 (48.6%) | 411 (30.0%) |

| Medium | 686 (29.6%) | 367 (30.0%) | 319 (29.1%) | 273 (28.8%) | 413 (30.1%) |

| High | 761 (32.8%) | 280 (22.9%) | 481 (43.9%) | 214 (22.6%) | 547 (39.9%) |

| Cognitive social capital | |||||

| Low | 2037 (87.8%) | 1125 (91.9%) | 912 (83.3%) | 870 (91.8%) | 1167 (85.1%) |

| High | 282 (12.2%) | 99 (8.1%) | 183 (16.7%) | 78 (8.2%) | 204 (14.9%) |

| Structural social capital | |||||

| Low | 1349 (58.2%) | 745 (60.9%) | 604 (55.2%) | 575 (60.7%) | 774 (56.5%) |

| High | 970 (41.8%) | 479 (39.1%) | 491 (44.8%) | 373 (39.3%) | 597 (43.5%) |

Symptoms of depression: PHQ-8 score higher than 10; symptoms of anxiety: GAD-7 score higher than 10.

Being a victim of bullying significantly increased the odds of being a case of depression and anxiety, even after adjusting by sociodemographic variables and resilience levels (Table 2). Analysing the adjusted estimates, participants who experienced bullying more than a year ago had 2.39 times higher odds of reporting depression symptoms (OR=2.39; 95% CI [1.98, 2.89]); in comparison, those bullied within the past year had 3.58 times higher odds (OR=3.58; 95% CI [2.40, 5.34]), both compared to participants who were never victims of bullying.

Crude and adjusted logistic regressions for the association between bullying and depression and anxiety symptoms.

| Outcomes and exposures | Crude model | Adjusted model* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Outcome: symptoms of depression | ||||||

| Experienced bullying | ||||||

| Never (Ref.) | ||||||

| More than a year ago | 2.77 | 2.32, 3.31 | <.001 | 2.39 | 1.98, 2.89 | <.001 |

| In the last year | 4.26 | 2.90, 6.26 | <.001 | 3.58 | 2.40, 5.34 | <.001 |

| Outcome: symptoms of anxiety | ||||||

| Experienced bullying | ||||||

| Never (Ref.) | ||||||

| More than a year ago | 2.27 | 1.91, 2.72 | <.001 | 2.06 | 1.70, 2.48 | <.001 |

| In the last year | 4.62 | 3.23, 6.64 | <.001 | 4.01 | 2.76, 5.84 | <.001 |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; symptoms of depression: PHQ-8 score higher than 10; symptoms of anxiety: GAD-7 score higher than 10.

Similar results were found for anxiety symptoms. Adjusted estimates showed that participants who experienced bullying more than a year ago had 2.06 times higher odds of reporting anxiety (OR=2.06; 95% CI [1.70, 2.48]), while those bullied within the past year had 4.01 times higher odds (OR=4.01; 95% CI [2.76, 5.84]), both compared to participants who were never victims of bullying. The larger OR for recent bullying suggests a substantial increase in the risk of having symptoms of depression and anxiety when the bullying occurred more recently.

Individual resilience as a protective factor for the association between bullying and symptomsIn addition to the crude and adjusted logistic regression models shown in Table 2, we stratified the results by the tertiles of individual resilience and analysed the trend of odds (Table 3). Among individuals who were bullied more than a year ago, those with moderate and high individual resilience had lower odds of reporting symptoms of depression and anxiety compared with bullied individuals with low individual resilience.

Logistic regressions for the association between bullying and symptoms of depression and anxiety stratified by resilience levels.

| Outcomes and exposures | Low resilience | Moderate resilience | High resilience | Trend of odds p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | 95% CI | OR* | 95% CI | OR* | 95% CI | ||

| Outcome: symptoms of depression | |||||||

| Never (Ref.) | |||||||

| More than a year ago | 3.33 | 2.37, 4.67 | 2.07 | 1.49, 2.88 | 2.08 | 1.48, 2.91 | .005 |

| In the last year | 4.22 | 2.23, 7.98 | 3.57 | 1.50, 8.47 | 3.28 | 2.00, 7.54 | .845 |

| Outcome: symptoms of anxiety | |||||||

| Never (Ref.) | |||||||

| More than a year ago | 2.63 | 1.93, 3.58 | 1.52 | 1.10, 2.12 | 2.07 | 1.42, 3.02 | .010 |

| In the last year | 5.08 | 2.83, 9.11 | 2.47 | 1.14, 5.38 | 4.72 | 2.42, 9.20 | .294 |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; symptoms of depression: PHQ-8 score higher than 10; symptoms of anxiety: GAD-7 score higher than 10.

For depressive symptoms, compared to non-victims, individuals bullied more than a year ago with low individual resilience had 3.33 times higher odds (OR=3.33, 95% CI [2.37, 4.67]), those with moderate individual resilience had 2.07 times higher odds (OR=2.07, 95% CI [1.49, 2.88]), and those with high individual resilience had 2.08 times higher odds (OR=2.08, 95% CI [1.48, 2.91]). The difference in odds ratios across resilience levels among bullied individuals was statistically significant (p=.005).

For anxiety symptoms, compared to non-victims, individuals bullied more than a year ago with low individual resilience had 2.63 times higher odds (OR=2.63, 95% CI [1.93, 3.58]), those with moderate individual resilience had 1.52 times higher odds (OR=1.52, 95% CI [1.10, 2.12]), and those with high individual resilience had 2.07 times higher odds (OR=2.07, 95% CI [1.42, 3.02]). This difference in odds ratios across resilience levels was also statistically significant (p=.010).

We did not identify a significant trend of odds ratios among participants who were bullied in the last year (p>.05), suggesting that individual resilience may buffer the psychological impact of bullying only when the victimisation is not recent.

The role of bullying and individual resilience can be visualised in Fig. 1, where being a victim of bullying and exhibiting lower resilience is associated with a higher predicted probability of having symptoms of depression and anxiety. On the contrary, exhibiting higher resilience decreases the expected likelihood of having symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Predictive probabilities of having symptoms of depression and anxiety across resilience levels with 95% confidence intervals. Note: Predicted probabilities were obtained from the margins of the logistic regression model adjusted by city, gender, age group, main occupation, education degree, cognitive social capital, and structural social capital.

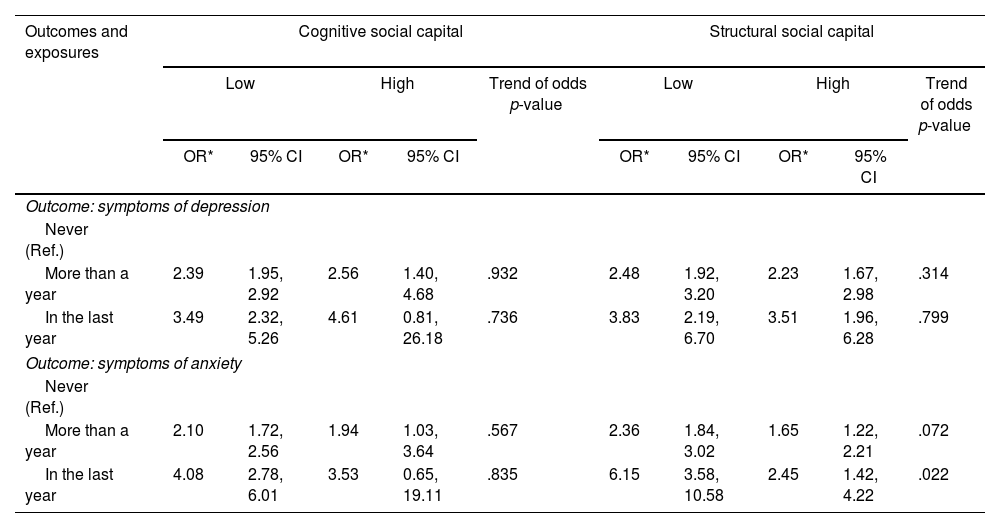

We stratified the association between being a victim of bullying and symptoms of depression and anxiety by cognitive and structural social capital levels (Table 4). The odd ratios remain consistent across strata. Wald's tests of trend did not show significant trends for depression across cognitive or structural levels (all p>.05), and only structural social capital in participants bullied in the last year showed a statistically significant difference for anxiety (p=.022). However, these results should be interpreted with caution, since when bullying occurred in the last year, most odds ratios had wide confidence intervals, limiting the precision of comparisons.

Logistic regressions for the association between bullying and symptoms of depression and anxiety stratified by cognitive and structural social capital levels.

| Outcomes and exposures | Cognitive social capital | Structural social capital | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Trend of odds p-value | Low | High | Trend of odds p-value | |||||

| OR* | 95% CI | OR* | 95% CI | OR* | 95% CI | OR* | 95% CI | |||

| Outcome: symptoms of depression | ||||||||||

| Never (Ref.) | ||||||||||

| More than a year | 2.39 | 1.95, 2.92 | 2.56 | 1.40, 4.68 | .932 | 2.48 | 1.92, 3.20 | 2.23 | 1.67, 2.98 | .314 |

| In the last year | 3.49 | 2.32, 5.26 | 4.61 | 0.81, 26.18 | .736 | 3.83 | 2.19, 6.70 | 3.51 | 1.96, 6.28 | .799 |

| Outcome: symptoms of anxiety | ||||||||||

| Never (Ref.) | ||||||||||

| More than a year | 2.10 | 1.72, 2.56 | 1.94 | 1.03, 3.64 | .567 | 2.36 | 1.84, 3.02 | 1.65 | 1.22, 2.21 | .072 |

| In the last year | 4.08 | 2.78, 6.01 | 3.53 | 0.65, 19.11 | .835 | 6.15 | 3.58, 10.58 | 2.45 | 1.42, 4.22 | .022 |

OR: odds ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; symptoms of depression: PHQ-8 score higher than 10; symptoms of anxiety: GAD-7 score higher than 10.

Nevertheless, Fig. 2 suggests that a high cognitive social capital is associated with a decreased probability of having symptoms of depression and anxiety among participants who never experienced bullying or were bullied more than a year ago. This difference in predicted probabilities is absent among participants bullied in the last year. Therefore, cognitive social capital might have a small protective role in young people who were bullied more than a year ago, but the evidence for recent bullying cases is weak because of uncertainty in the estimates. Regarding structural social capital, the data do not show a significant difference in the predicted probabilities of having symptoms of depression and anxiety according to participants’ structural social capital levels.

Predictive probabilities of having symptoms of depression and anxiety across cognitive and structural social capital levels with 95% confidence intervals. Note: Predicted probabilities were obtained from the margins of the logistic regression model adjusted by city, gender, age group, main occupation, resilience, and education degree.

In this study, we aimed to explore the association between being a victim of bullying and the presence of symptoms of depression and anxiety among adolescents and young adults from low-income communities in Latin America. We also aimed to evaluate whether participants’ individual resilience and cognitive and structural social capital modified the association between bullying and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Our findings suggest that bullying is significantly associated with increased odds of experiencing depression and anxiety. The odds of reporting depression and anxiety symptoms were higher if the bullying occurred in the last year compared to more than a year ago. Importantly, we also found evidence that individual resilience and cognitive social capital decreased the likelihood of depression and anxiety symptoms among the bullying victims. However, we did not find such a protective effect with structural social capital.

Comparison with the literatureIn line with our study, a large body of research has linked bullying to adverse mental health outcomes.1,8–10 Bullying victims are in a state of sustained environmental psychological distress.53,54 The constant humiliation, exclusion, or aggression could also impact their self-esteem and self-worth.55 Additionally, the social exclusion involved in bullying could lead to deep feelings of loneliness.9

Even if participants were no longer bullying victims, they still had a higher likelihood of having symptoms of depression and anxiety compared to participants who were never bullied. In line with this result, studies have linked bullying with long-term effects on brain functioning, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.53,55

We found that trait resilience helped mitigate the negative impact of bullying, as seen in other studies with Chinese adolescents.22,23 These results align with the resilience theory, which proposes that individuals with higher trait resilience have a higher chance of successfully handling stress and adversity.14 Therefore, these internal assets, such as adaptability, persistence, and cognitive restructuring, have been found important in shielding individuals against the detrimental effects of bullying.

Additionally, feelings of neighbourhood belonging, trust, safety, and relationship quality, measured through cognitive social capital, helped mitigate the negative impact of bullying. However, structural social capital, which refers to formal networks and institutional involvement, did not have an apparent protective effect against depression or anxiety. Similarly, a systematic review56 found an inverse relationship between cognitive social capital and common mental health disorders; nevertheless, there was no clear association between structural or ecological social capital and mental health disorders. This suggests that being part of different community networks and being politically active in your neighbourhood may not be enough to provide emotional support or reduce psychological vulnerability to bullying.18 On the contrary, social harmony and community trust are seen as protective factors against mental health issues.

Policy implicationsThe findings have important implications for public health and educational policies to prevent bullying. Latin American governments and social organisations should focus on implementing preventive measures against bullying. Studies have found that interventions that target self-compassion significantly decrease bullying perpetration.8 Social support and classroom integration have also been associated with less bullying in the classroom.57

Additionally, therapeutic interventions should be implemented. For instance, Peru has a public platform called SíseVe where anyone (e.g., victim, teacher, school psychologist, administrative, etc.) can report school violence confidentially.58 The public administration of the educational institution then implements different interventions, such as psychological support for both the victim and perpetrator. The government and educators from Latin America should guarantee that vulnerable populations, such as young people, can have a space to denounce violence and get protection and physical and psychological attention.

Programs that foster individual resilience and social capital should also be prioritised. A recent systematic review identified that resilience-based interventions that use multicomponent techniques (i.e., combining several protective factors) are the most beneficial.59 These interventions have targeted leadership, problem-solving when facing stressful situations, mindfulness, and self-efficacy through workshops or individual sessions.60–62 Regarding social capital, a systematic review identified that interventions comprising community engagement, educational programs, and neighbourhood projects were associated with better mental health outcomes among the communities.63

Strengths, future directions, and limitationsOne of this study's strengths is that we take an ecological and comprehensive approach to resilience, incorporating both trait resilience and social capital as a community resource. Another strength is that we analysed data from a large sample of underrepresented groups living in deprived communities in Latin American cities, contributing to a region with limited prior research. The use of multivariable modelling allowed us to adjust for several potential confounders, strengthening the robustness of our findings. To our knowledge, this is also the first study to examine social capital as a protective factor against bullying in young people.

Future research could use a longitudinal design that explores how individual resilience and social capital develop over time and whether their protective effects persist across the lifespan. Interventions or programmes that aim to promote individual resilience and social capital among vulnerable youth communities could also be tested. Additionally, future studies could explore if our results are consistent across different socioeconomic contexts. Finally, a detailed measure of bullying experiences that differentiates type, duration, frequency, and intensity of victimisation should be included in future studies.

However, this study has limitations. Firstly, we used a convenience sample, which could introduce bias into the study. Although the participants had the same probability of being cases, the controls were not systematically obtained and were recruited in different settings. Also, our instrument did not measure detailed data about bullying: we could not know the type of bullying participants experienced (e.g., physical, verbal, social, cybernetic), the motive (e.g., socioeconomic, sexual orientation), nor the duration, frequency, and intensity of the abuse. Furthermore, the self-report nature of this instrument could also generate social desirability bias and inaccuracy when estimating the event's timing. Additionally, the observational nature of the design makes it hard to confirm a causal relationship between the study's variables.

ConclusionsOur study shows that, among youth from deprived neighbourhoods in Latin America, being a bullying victim is associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety, but the damage is not inevitable. Young people with higher individual resilience and cognitive social capital seem to be better equipped to withstand this harmful life experience, which appears to have a long-term detrimental effect. However, structural social capital offered no such protection. Protecting youth mental health in deprived urban settings requires more than anti-bullying policies alone; there is a need for strategies that promote individual and community resources that act as a buffer for psychopathological symptomatology. For educators, policymakers, and mental health professionals, this means implementing programmes in schools and communities to promote mental health among vulnerable individuals.

Ethical approvalUniversidad de Buenos Aires in Argentina (dated October 2nd, 2020), Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Colombia (ref. FM-CIE-1138-20), Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Peru (ref. Constancia 581-33-20), and Queen Mary University of London in the UK (ref. QMERC2020/02).

FundingThis work was supported by the Medical Research Council [grant number MR/S03580X/1].

Competing interestsThe authors declare no competing interests.

We would like to thank all participants of the study for sharing their data, experiences and views with us.