Do we form mental models which bear an analogical relation to the real world like those of a photograph? Has the language of thought an analogue nature (it makes use of mental imagery) or whether it is exclusively of digital nature like language?

ObjectivesThe basic aim of the present study is to contribute to the ongoing work on mental imagery by extending the research to an unexplored area that of mental partitioning.

MethodsThe present research sample consisted of 498 participants (234 males and 264 females). We used the SPSS software package in order to analyze our data.

ResultsAccording to our results, we detected significant peculiarities in the cognitive performance of the participants in the tasks of mental partitioning of the Moebius strip, indicating certain limitations inherent in human thinking.

ConclusionsThe position we are led to adopt is closer to that of Pylyshyn (2003), who maintained that visual mental imagery depends on abstract form of thought and on previous knowledge. Specifically, it rests on previous abstract propositional thought and knowledge rather than on concrete perceptual processes like the ones proposed by Kosslyn and Sheppard. The present work investigates a potentially valuable theoretical basis in imagery research for understanding maladaptive imagery across various related clinical disorders, while encouraging multidisciplinary approaches among cognitive psychological/neuroscientific and clinical domains.

¿Formamos modelos mentales que guardan una relación analógica con el mundo real como los de una fotografía? ¿Tiene el lenguaje del pensamiento una naturaleza analógica (hace uso de imágenes mentales) o es exclusivamente de naturaleza digital como el lenguaje?

ObjetivosEl objetivo básico del presente estudio es contribuir al trabajo en curso sobre la imaginería mental extendiendo la investigación a un área inexplorada que es la partición mental.

MétodosLa muestra de la presente investigación estuvo compuesta por 498 participantes (234 varones y 264 mujeres). Usamos el paquete de software SPSS® para analizar nuestros datos.

ResultadosDe acuerdo con nuestros resultados, detectamos peculiaridades significativas en el desempeño cognitivo de los participantes en las tareas de partición mental de la tira de Moebius, indicando ciertas limitaciones inherentes al pensamiento humano.

ConclusionesLa posición a la que nos vemos llevados a adoptar se acerca más a la de Pylyshyn (2003), quien sostenía que la imaginería mental visual depende de formas abstractas de pensamiento y de conocimientos previos. Específicamente, se basa en el pensamiento y el conocimiento proposicionales abstractos previos más que en procesos de percepción concretos como los propuestos por Kosslyn y Sheppard. El presente trabajo investiga una base teórica potencialmente valiosa en la investigación de imágenes para comprender las imágenes desadaptativas en varios trastornos clínicos relacionados, al tiempo que fomenta enfoques multidisciplinarios entre los dominios cognitivos psicológicos/neurocientíficos y clínicos.

We create representations to calculate space, distances and directions, and for that reason, our brain includes a guidance system that utilizes neural algorithms.1 The spatial representational system is mainly understood through its use of algorithms and innate maps, but further research is needed to understand how different cognitive factors are incorporated and produce the aforementioned representations.1 Is “thought” to be understood as a series of words forming sentences or as images? There has been an important disagreement between Kosslyn and Pylyshyn on the nature and role of mental images.2,3 The core of their difference lies on whether “language of thought” is exclusively digital (similarly to language) or analogical, incorporating mental images. The basic arguments for a mental image model of thought are based on neuropsychological evidence. Farah found that the same brain regions are activated during both mental representation and actual perception, while Bishiah found that brain traumas that affected perception, also affected the ability to create mental images.4,5 Pylyshyn on the other hand, argues that all mental images are guided by “cognitive penetrability,” thus on their very basis, are manipulated by certain propositional elements. We come to the conclusion that the relationship between “seeing” and “knowing” is more complex, not just on the level of the mental image level, but also on the level of perception.6,7 Given this difficulty, Kargopoulos hinted towards further research, featuring shapes and solid objects, for which subjects have no prior extensive knowledge.7 This would force subjects to use non-semantic strategies of representation, meaning mental imagery. Hinton's (1979) cube problem conforms to these requirements. Hinton's problem aligns with the idea that spatial tasks (especially tasks with cubes that change layout) are guided by propositional cues (our knowledge about squares) and supports Pylyshyn's position.8 Using one of the simplest objects, a cube, Hinton showed that as soon as this shape changes its mental arrangement in space, even suspicious – as to the nature of the experiment – participants will make mistakes that are not present when they manipulate a mental image of the cube sitting on its typical array.

Mental partitioningTaking into account the limited research on mental partitioning, no study has examined the underlying mechanisms of mental partitioning, and the limits of it revolving simple, understandable objects for which subjects didn’t have prior knowledge (ex. Moebius strip), as well as its relationship to performance in spatial tasks. In any case, a basic challenge remains for cognitive psychology: Are there any mental partitioning tasks that may hint towards the nature of mental representations and is the theory of cognitive penetrability sufficient to establish a new propositional theory of perception?

MethodologyThis study is anonymous and all participants have given a written consent for their voluntary participation.

Our first experiment tested whether language of thought, on the premise of it being the basis for all cognitive tasks, is exclusively digital or analogical utilizing mental images. We used 2 groups: a control and an experimental one. In the control group, we presented a Moebius strip and asked them to mentally partition it. In the experimental group, we presented them with a Moebius strip and asked them to mentally represent it, then we removed it from their field of perception, and when the subjects were sure that they could adequately represent it, we asked them to mentally partition it. We hypothesized that the same degree of success between the two groups would support Kosslyn's views, whereas lower scores in the experimental group would support Pylyshyn's.2,3 What happened was something we did not expect. After reviewing their scores, we found that there was a total failure in either of the two. The subjects’ failure to mentally partition Moebius strip s led us to a new series of studies, focusing on the particularity of Moebius strip and the process of mental partitioning itself. We tried to investigate possible cognitive biases, a pattern of divergent judgements that is activated during mental partitioning and the effect of “cognitive schemas” during this task. To summarize, we tested whether there are cases where problem solving is guided by established and unchanging “cognitive schemas” that affect not only mental images but also perception.9

To investigate our hypothesis, we evaluated scores from two different tasks: Hinton's cube and Moebius strip.8 Our basic goal was to answer whether:

- a)

established knowledge does affect thought and perceptual ability negatively leading to cognitive biases,

- b)

Pylyshyn's theory of cognitive penetrability is applicable in the case of mental partitioning of an object and what are the differences between Pylyshyn's and Kosslyn's views on the nature of our mental representations,

- c)

how the scores in mental imaging tasks differ from scores in the mental partitioning ones. Our second goal was to investigate the relationship between visuo-spatial skill and the ability for mental partitioning in healthy subjects, using the Moebius strip, in order to examine the hypothesis that mental partitioning is a sub-skill of mental imaging presenting a high level of difficulty for subjects. Our third goal was to examine whether the influence of personal factors (such as: gender, age, level of education) affects performance in mental partitioning tasks.

We used the SPSS software package in order to analyze our data. We used: one-way ANOVA, binomial test, t-test to examine quantitative variables, chi squared independence test to examine categorical variables and adjusted standardized residuals to examine statistically significant Chi-square results. For large samples, adjusted standardized residuals approach normal distribution. Positive adjusted standardized residuals>1.96 indicate statistically significant relationship between the variables in those cells.

Study 1Study 1 – Research planWe carried two studies: The first one attempted to answer our first goal. Initially, we divided our subjects into 2 sub-groups: (a) a control group (N=186, 54.1%), in which subjects were presented with a Moebius strip and were asked to mentally partition the shape they had visual contact with, and (b) an experimental group (N=158, 45.9%), in which subjects were presented with a Moebius strip, while witnessing its creation process. After they confirmed that they could mentally represent it adequately, we removed the strip from their visual field and asked them to mentally partition its mental image. This plan attempted to investigate potential differences between perceptual and mental imaging process in mental manipulation tasks such as the one using the Moebius strip. To investigate whether, apart from mental images, people use propositional representations (Pylyshyn's views), we administered 3 tasks6:

- a)

In the first task (Hinton 1), the correct answer was based on the subject's prior knowledge on cubes (propositional representation).

- b)

In the second task (Hinton 2), the correct answer was based on the mental manipulation of the cube (analogical representation).

- c)

In the third task (Moebius strip mental partitioning), we hypothesized that the subjects’ prior knowledge (Whatever you cut gets separated into 2 pieces) would affect them and lead a significant percentage to answer incorrectly, supporting the view that this task involves mainly propositional and not analogical representations.

The basic hypothesis here is that there are spatial tasks, like mental partitioning of Moebius strip that do not utilize mental images but are subjected to what Pylyshyn identified as cognitive penetrability. Taking into account that no participant had prior knowledge of Moebius strip, the scores in partitioning tasks would not be affected by the perceivable object but by their prior knowledge about how the world works.6 We predicted that the majority of the subjects would not put enough effort in the task using already established mental schemas and their properties. If the subjects could visualize the two simple shapes (Hinton's cube and Moebius strip), then potential low scores in spatial tasks could hint towards increased difficulty in mental image manipulation. Specifically, regarding the mental partitioning of Moebius strip task answers such as “cutting the strip will give us 2 new strips” could support the idea that mental images depend on an established worldview that is on abstract propositional knowledge and not on perceptual processes.6 Following the idea mentioned above, these two specific tasks (Hinton's cube mental manipulation and Moebius strip's mental partitioning) would be based on propositional representations, meaning that mental imaging processes are guided by propositional factors (Hypothesis 1).

Study 1 – ParticipantsIn the first part of the study a total of 344 subjects where tested. Of them 157 were male (45.6%) and187 were female (54.4%). Participants were categorized in 2 different age groups: above 25 years old (born in 1987 or earlier) (N=166, 48.3%) and below 25 years old (1988 and after) (N=178, 51.7%), in order to examine age factors in the tasks given.

Study 1 – Tasks- 1)

Hinton 1 –Identifying the number of free edges of a mentally depicted Hinton's cube

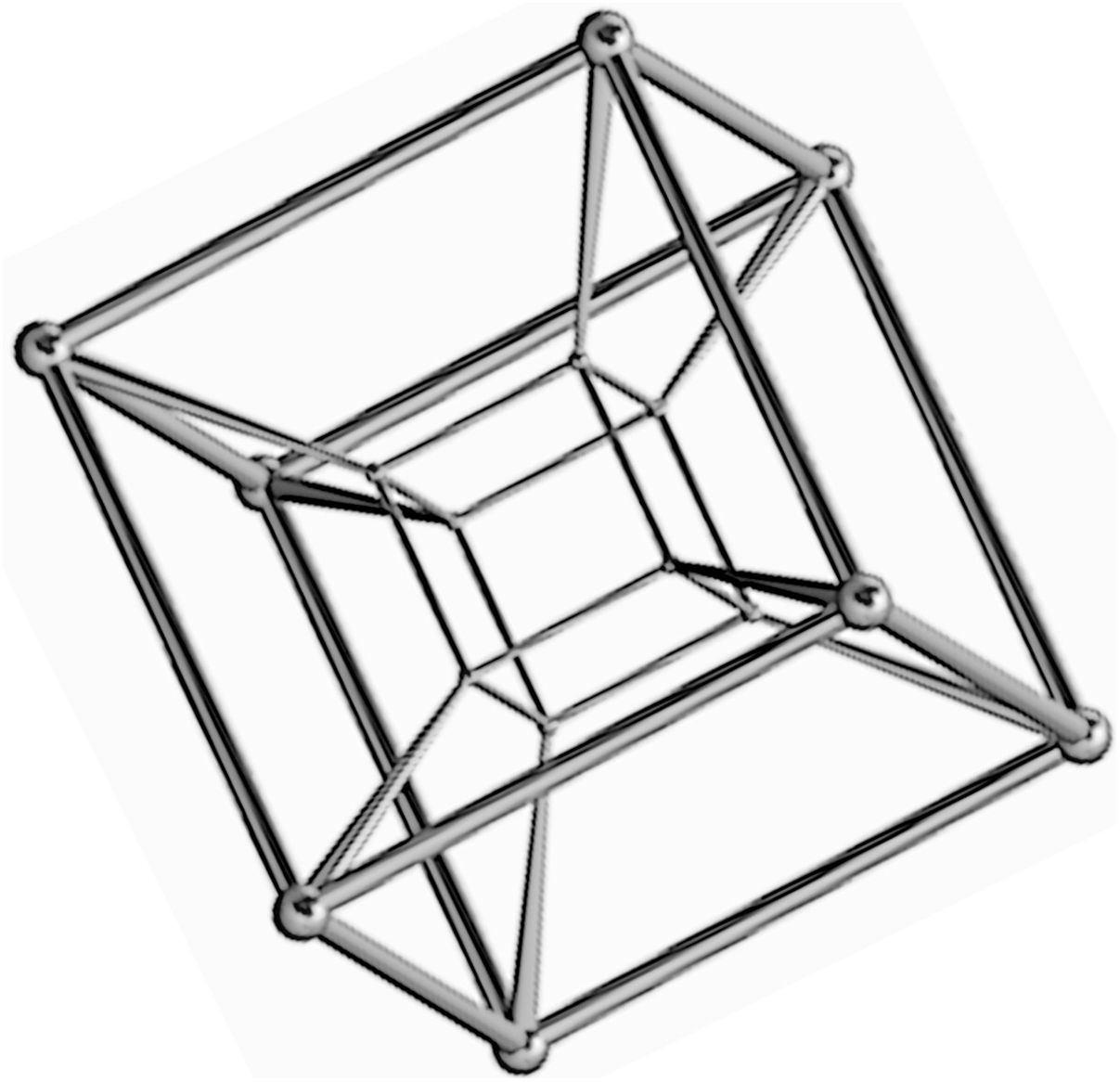

We asked the subjects to find the number of free edges in a mental depicted cube (30cm each side) when that cube was standing on either of its edges (Fig. 1).

- 2)

Hinton 2 – Locating the free edges of a mentally depicted Hinton's cube in space

The study of the ability of mental partition of three-dimensional objects (in real perception or mentally) helps us to understand the ways in which an individual may work in order to find solutions for which they possess no a priori satisfactory answers. Mental dichotomy can lead us to the acquisition of new knowledge, while important data can emerge for learning processes in general. A classic partition task is the bisection of Hinton (1979) cube: “Imagine a cube attached to one of its vertices and then cut it along the equator of its outlined sphere. What would be the shape of the cut surface if you removed the top?” Most people answer that it is going to be a square, but that is not correct, as it is actually going to be a regular hexagon. This figure is included in order to illustrate which were the objects presented to the participants, as this would allow the reader a better understanding of the experimental paradigms that were used as well as their outcomes.

The second task demanded the mental manipulation of the cube. We asked the subjects to pinpoint the cubes edges in space.

- 3)

Mental partitioning of Moebius strip task

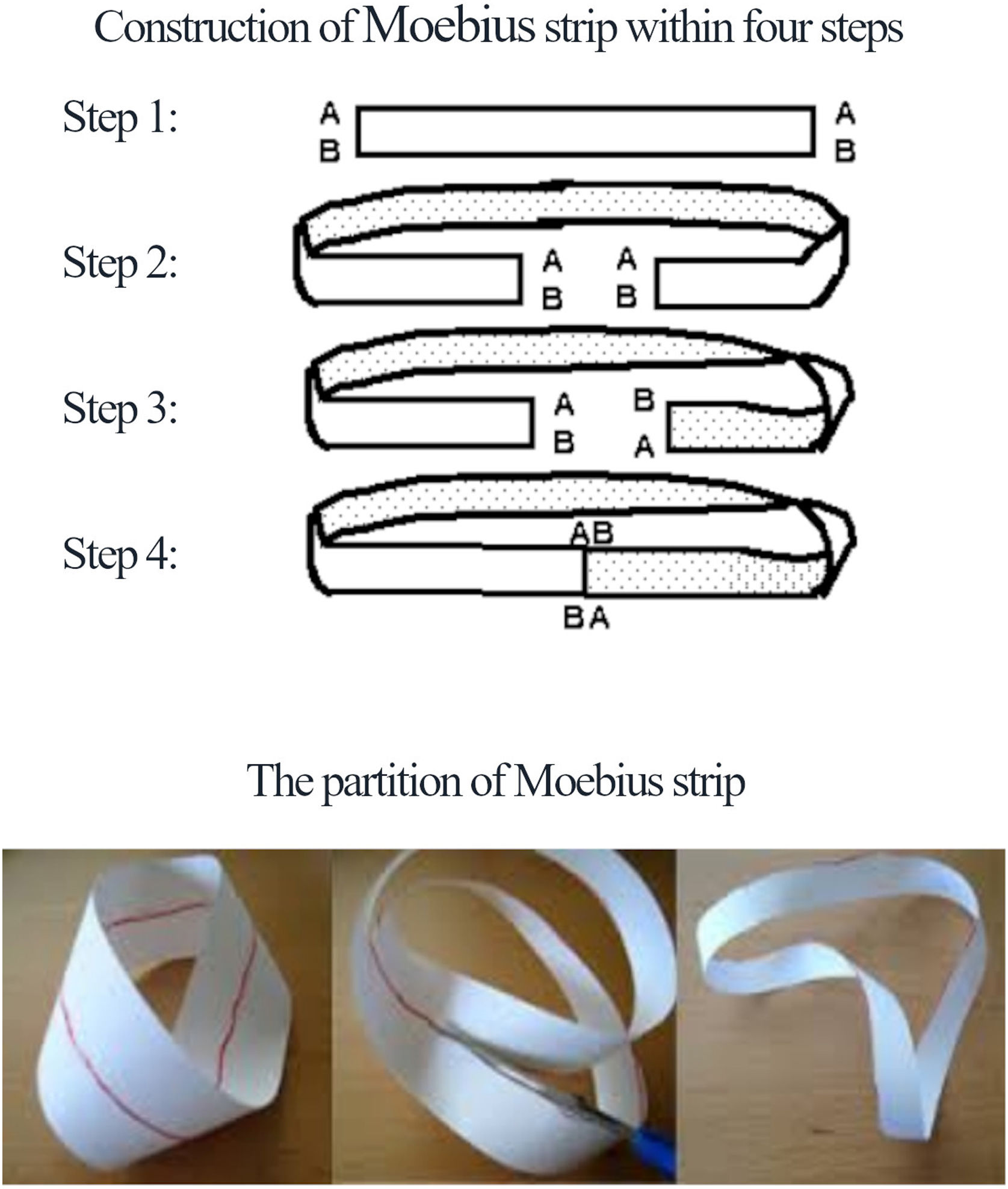

We asked the subjects to imagine what the partitioning of a Moebius strip along its axon would give us. They were also given information about the strip's creation process (Fig. 2).

A Moebius strip, band, or loop is a sui generis mathematical object standing for the simplest non-orientable surface and was named after the mathematician August Ferdinand Möbius who discovered it in 1858. It is a surface with only one side (when embedded in three-dimensional Euclidean space) and only one boundary curve, while every classical geometric shape (either convex or nonconvex) has two sides. If a “traveler” walked along the entire length of this tape, they would return to the starting point having traversed each part of the tape (its direction is “lost” for the traveller circulating on it). If the strip got cut lengthwise, a larger one would result. If one went on to re-cut the latter lengthwise, two strips would appear one inside another, similar to chain links. This figure is included in order to illustrate which were the objects presented to the participants, as this would allow the reader a better understanding of the experimental paradigms that were used as well as their outcomes.

From the 344 participants, 160 (46.5%) answered correctly in the Hinton 1 task, 31 (9%) answered correctly in the Hinton 2 task and 9 participants (2.6%) correctly partitioned Moebius strip (Table 1). Gender and age did not affect scores in the visual – spatial tasks (Hinton 1 and Hinton 2). Gender and age effects are present in the Moebius strip partitioning task. The correct answer was given by 6 males (1.7%) and 3 females (0.87%). Younger participants (<25) scored higher than the >25 group. From a total of 9 correct answers, 6 (1.7%) came from the younger group and 3 (0.87%) from the older. There were 7 correct answers in the control group (the group that were in visual contact with the Moebius strip) and 2 correct answers in the experimental one (Table 1).

(a) Frequency of answers in the tasks of the 1st study; (b) Frequency of correct answers in Moebius’ strip partitioning (age*, gender*, experimental condition*, Moebius’ strip mental partitioning*).

| (a) Tasks | Correct answers | Percentage | False answers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinton 1 | 160 | 46.5% | 184 | 53.5% |

| Hinton 2 | 31 | 9.00% | 313 | 93.00% |

| Moebius’ strip | 9 | 2.6% | 335 | 97.4% |

| (b) Correct answers in Moebius’ strip partitioning | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 6 | Male |

| 3 | Female |

| Gender | |

| 6 | Below 25 years old |

| 3 | Above 25 years old |

| Experimental condition | |

| 7 | Control group |

| 2 | Experimental group |

From these results we can infer that success rates in the mental partitioning tasks were low. A significant rate of success was present in the younger group. The group that had visual contact with the Moebius strip had a higher rate of success than the group that could only mentally manipulate without seeing it, however this result cannot support the idea that mental manipulation is facilitated by the perceptual condition.

Performance relationship to Hinton 1 and Hinton 2 tasksTo identify the statistical significance of the relationship between performance of the participants in Hinton 1 (Propositional representation) and Hinton 2 (Analogical representation) tasks, a chi-squared independence check was applied. There was a statistically significant correlation between performance in Hinton 1 and Hinton 2 tasks, Chi-squared (N=129, BE=1)=39.18, p<.001. Of the 160 participants who responded correctly to the Hinton 1 task, only 31 (24.03%) responded correctly to Hinton 2 (Analogical representation) (Table 2). It seems that most people who responded correctly to the first task had mistakenly manipulated the mental image in the second one (Hinton 2). This confirms Hypothesis 1 (Table 2).

(a) Frequency of correct answers (Hinton 1*, Hinton 2*); (b) Frequency of correct answers (Hinton 1*, Moebius’ strip mental partitioning*); (c) Frequency of correct answers (Hinton 2*, Moebius’ strip mental partitioning*).

| (a) Correct answers in Hinton 1 and Hinton 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hinton 1 | Total | ||

| False answers (4 vertices) | Correct answers (6 vertices) | ||

| Hinton 2 | |||

| Correct vertices array | 0 | 31 | 31 |

| False vertices array | 184 | 129 | 313 |

| Total | 184 | 160 | 344 |

| (b) Correct answers (Hinton 1*, Moebius’ strip mental partitioning*) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hinton 1 | Total | ||

| False answers (4 vertices) | Correct answers (6 vertices) | ||

| Moebius’ strip partitioning | |||

| Correct partitioning | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| False partitioning | 184 | 151 | 335 |

| Total | 184 | 160 | 344 |

| (c) Correct answers (Hinton 2*, Moebius’ strip mental partitioning*) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hinton 2 | Total | ||

| False vertices array | Correct vertices array | ||

| Moebius’ strip partitioning | |||

| Correct partitioning | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| False partitioning | 311 | 24 | 335 |

| Total | 313 | 31 | 344 |

There was a statistically significant relationship in participants’ performance between mental partitioning and Hinton 1 tasks, Chi-squared (N=9, BE=1)=10.62, p<.001. Those who responded correctly to mental partition tasks were also able to find the correct number of vertices in Hinton 1 (Propositional representation) task (N=9) (Table 2).

Performance relationship between mental partitioning of Moebius strip and Hinton 2 tasksThere was a statistically significant relationship of participant performance between the Moebius strip and Hinton 2 tasks, chi-squared (N=24, BE=1)=53.29, p<.001. Of the 31 subjects who responded correctly to the Hinton 2 (Analogical representation) task, 24 (77, 5%) gave the wrong answer to the mental partitioning task. This confirms Hypothesis 1 (Table 2).

Relationship between the experimental conditions (mental partitioning of the strip) and performance in the Moebius strip taskIn order to examine the hypothesis that perceptual processing does not facilitate the mental processes in partitioning of the Moebius strip task (Hypothesis 2), we compared the performance of the two experimental groups. For the statistically significant relationship in the performance between the two groups to be identified, the chi-squared independence check was applied. There was a statistically significant correlation in performance between the experimental and control groups, chi-squared (N=156, BE=1)=43.59, p<.001. Of the 186 subjects who had visual contact with the strip while trying to partition it mentally (control group), 179 (96.24%) gave the wrong answer and of the 158 subjects who tried partitioning its mental image (experimental group), 156 (98.74%) gave also the wrong answer (Table 3). Binomial test for success in mental partitioning task showed that there's a statistically significant difference in the percentage of those who failed in the control (p<.001) and the experimental groups (p<.001). The two groups showed no differences in their performance. This confirms Hypothesis 2 (Table 3).

Relationship between age and performance in Hinton 1, Hinton 2 and mental partition of Moebius strip tasksAccording to the results from the first two tasks (Hinton 1 and 2) there were no significant differences in performance amongst subjects from the two age groups. Of the 9 subjects who responded correctly to the Moebius strip task, the younger (under 25) showed better performance (6 subjects, 66.7%). The Binomial test for success or failure in each age group in Moebius strip task showed a statistically significant difference for younger subjects (p<.001).

Relationship between gender and performance in Hinton 1, Hinton 2 and Moebius strip tasksAccording to the results from the first two tasks (Hinton 1 and 2) there were no significant differences in performance between men and women. Of the 9 subjects, however, who responded correctly in the mental partitioning task, men, showed a better performance (6 subjects; 66.7%). The binomial test for success or failure between men and women in the Moebius strip task showed that there was a statistically significant difference over men (p<.001).

Discussion – study 1According to the results from the first study, only 46.5% of the participants responded correctly in the Hinton 1 task. Assuming that when they tried to solve Hinton 1 task, people used a virtual mental representation, then we could say that it didn’t help them to answer correctly. We claim that the unusual position of the cube and its vertices makes its virtual representation a quite difficult task, we also claim that those who gave the correct answer either used the propositional representation: “The cube has eight vertices, if I remove two then six remain” or they were really good at manipulating the cube's mental image. If the latter were true, then those participants should have showed a higher rate of success in the task that followed, which clearly required the mental manipulation of the inverted cube's image (Hinton 2). It seems that there are spatial tasks that in order to be solved need not only the manipulation of a virtual representation but most importantly the use of some prior knowledge in the form of propositional representation. Subjects in their vast majority found it more difficult to manipulate the cube's mental image in the second task. Of the 344 participants, only 31 managed to give the correct number of vertices in space. Though people had a hard time manipulating the cube's mental image, their success rates were much higher for the Hinton 1 task in which propositional representation was more accessible. Only 9 of the 344 participants could find the correct answer for the Moebius strip task in which mental manipulation of the strip image was impossible. This task seems to have been catalyzed by the prior knowledge: “Whatever you cut gets separated into two pieces” (Cognitive penetrability) which led 97.3% of the participants to the wrong answer. With regard to the variables we examined in mental partitioning it seems that age and gender tend to influence performance with young (under 25) men being better, though the small number of participants who responded correctly prevents us from further supporting this case. One particular interest was the fact that the condition of having visual contact with the strip, while trying to mentally partition it did not increase the percentage of correct responses significantly. This means that Pylyshyn's cognitive penetrability should be also applied to perceptual phenomena.6,7 The experimental groups comparison shows that participants who were in visual contact with the Moebius strip showed a better performance, though these results cannot support that mental partition is facilitated by being in perceptual contact with the object.

Study 2Study 2 – research planThe second study attempted to confirm our initial hypothesis that the mental partitioning of Moebius strip is guided by cognitive penetrability. It attempts to show that mental partitioning of Moebius strip, as a mental manipulation task, reaches the limits of human cognition and problem solving. Finally, the second study investigates the effects of three different sub-groups (1. Architects, 2. Psychologists, 3. Typical population) and of personal factors on spatial and partitioning problem solving.

Study 2 – HypothesisA second hypothesis states that the mental partitioning task would not be facilitated by the perceptually available Moebius strip (Hypothesis 2). Low scores in mental partitioning tasks are expected to confirm the existence of cognitive penetrability (Hypothesis 1).6 High correlation is also expected between spatial perception and mental partitioning tasks (Anderson, 1981) (Hypothesis 3). We expect that gender will be a differentiating factor as Voyer, et al. (1995) found that males score higher in certain spatial tasks, including mental partitioning (Hypothesis 4).10 Younger subjects are also expected to score higher than older ones (Hypothesis 5).11,12 Lastly we hypothesized that the group of architects would score higher than the other 2 groups (Hypothesis 6).10

Study 2 – ParticipantsA total of 154 subjects participated in this study. They were divided in 3 sub-groups: (a) a group of psychology students; (b) a group of architecture students; and (c) a typical population group. Specifically, 48 participants were architecture students (4th or 5th year) from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 33 were psychology students (3rd year or above) from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the rest came from typical population. Regarding gender, 77 were male and 77 female. Regarding age, 2 groups were formed: (a) above 25 years old (N=77, M=53.8) and below 25 years old (N=77, M=21.2). 2 groups were also formed based on educational level: (a) 12 years or below (N=41), (b) 13 years or above (N=113). Our sample did not include people with language or other problems (visual, auditory, psychopathology, etc.)

Study 2 – Tasks- A)

Spatial ability tasks

Ropes: We presented our participants with a picture of 6 different ropes entangled together. We asked them to tell us if each rope would create a knot when pulled. Each success was awarded with 1 point.

- 1)

Mental paper folding: We presented 20 instances where it was required from the participants to mentally fold a sheet of paper, pierce it and choose the correct solution from 5 alternatives as to how the holes would be arrayed if we unfolded that particular.13 Each success was awarded with 1 point.

- 2)

Hinton's cube – 2: The task is the same as the one described in Study 1. We awarded 14 points if all the edges were correctly arrayed in space (14 point=max score), 7 points if the participant arrayed at least 3 edges correctly and 0 points if the participant arrayed less than 3 correctly. The total amount of points a participant could gather in the second study was 40.

- B)

Mental partitioning tasks

The tasks administered were created specifically for the goals of the present study based on previous finding.7 Cronbach's a was deemed sufficient (a=.81).

- 1)

Mental partitioning of the course of 2 trains along a Moebius strip: We presented our subjects with a Moebius strip (3cm width, 25cm length). We asked them to imagine the reverse lengthwise course of two train starting from six different points of origin on the strip. The participants had to answer if the 2 trains would eventually meet on the strip. One point was awarded for each success.

- 2)

Mental partitioning of the angle of an analogical clock's indicators: We asked the participants to mentally partition the angle created by the indicators on an analogical clock. The task had 20 items and one point was awarded for each success.

- 3)

Mental partitioning of a Moebius strip: We presented our participants with the process of creating a Moebius strip and asked them to describe the shape produced if we cut the strip lengthwise. One point was awarded for each success.

- 4)

Mental partitioning of a Moebius strip with alternatives: Each participant was presented the strip and asked to mentally partition it lengthwise starting from a random point of origin. When they were finished they had to choose from 9 different alternative choices regarding the new shape produced. The answers were coded as “correct” or “incorrect” for the purpose of Binomial Test.

In order to investigate the correlation in overall performance between visual competence and mental partitioning tasks we applied Pearson correlation coefficient. The overall performance in visual competence tasks showed a statistically significant correlation with performance in mental partitioning tasks r=.75, p<.001. There was a positive correlation to performance in visual competence and mental partitioning tasks. This confirms Hypothesis 3.

The relationship between profession and overall performance in visual competence tasksANOVA analysis to compare the mean scores in 3 visual competence tasks between the three different profession groups showed statistically significant results. Specifically, the effect of the profession factor was statistically significant [F(2.151)=12.64, p=.001]. After making adjustments according to Bonferroni, regarding the number of comparisons we found statistically significant differences between the mean scores of the professions, paired t=(104)=1.37, two-way p<.001. The mean scores of the architecture group (M=24.02, SD=7.2) were significantly higher than those of the typical population (M=18.88, SD=7.03) and psychology groups alike (M=16.97, SD=5.57). The architecture students had higher scores than the psychology students and the people working typical jobs. This partially confirms Hypothesis 6.

Relationship between profession and overall performance in mental partitioning tasksANOVA analysis to compare the mean scores in mental partitioning tasks between the three different profession groups showed statistically significant results. Specifically, the effect of the profession factor was statistically significant [F(2.151)=3.04, p<.005]. After making adjustments according to Bonferroni, about the number of the number of comparisons, we found statistically significant differences between the mean scores of the professions t(104)=1.54, p<.005). The mean scores of the architecture group (MO=15.19, TA=8.27) were significantly higher than those of the typical population (MO=12.37, TA=6.94 and psychology group (MO=11.58, TA=6.53). This confirms Hypothesis 7.

Relationship between age and overall performance in spatial reasoning tasksANOVA analysis to compare the mean scores in spatial reasoning tasks between the 2 age groups (above 25 and below 25) showed statistically significant results. Specifically, the effect of age factor was statistically significant (F151=14.34, p<.000). The mean scores for “below 25” age group (MO=22.05, TA=7.93) were statistically higher that those of the “above 25” group (MO=17.76, TA=5.73). Participants who were aged below 25 years scored higher in spatial reasoning tasks.

Relationship between age and overall performance in mental partitioning tasksANOVA analysis to compare the mean scores in mental partitioning tasks between the two age groups (above 25 and below 25) showed statistically significant results. Specifically, the effect of age factor was statistically significant (F152=6.96, p<.000). The mean scores for “below 25 age” group (MO=14.51, TA=8.48) were statistically higher than that of the “above 25” group (MO=11.41, TA=5.49). Participants that were below 25 years old scored higher in mental partitioning tasks. This confirms Hypothesis 6.

Task: “Alternative solutions to mental partitioning of Moebius strip”For the purposes of this study, the answers provided in the task were participants had to choose from 9 alternative solutions to the mental partitioning of Moebius strip, were of particular interest (Table 4).

Frequency of answers in alternative answers task.

| Alternative answers | Frequency of answer | False percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 2 large collars, one inside the other | 8 | 5.2% |

| 1 bigger Moebius’ strip, half in width | 8 | 5.2% |

| 2 new Moebius’ strips, one inside the other, half in width | 5 | 3.2% |

| 1 big simple collar | 8 | 5.2% |

| 2 separate Moebius’ strips, same as the original, half in width | 104 | 67.5% |

| 1 Moebius’ strip with 3 loops | 1 | 0.6% |

| 2 new separate, non-connected, simple collars | 2 | 1.3% |

| A cohesive piece, which I can’t identify | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2 separate pieces, which I can’t identify | 18 | 11.08% |

Out of the 154 participants, 137 (89%) chose a wrong answer revolving around the separation of the strip into 2 distinct pieces (answers: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9). 17 participants (11%) chose answers that had only 1 piece as the product of mental partitioning (answers: 2, 4, 6, 8), and of the 17, only 8 (5.2% from a total of N=154) gave the correct answer (second option). Binomial tests for the success or failure in the task of “Alternative solutions to the mental partitioning of Moebius strip” showed statistically significant differences over the participant's failure rate (p<.001). The percentage of participants who were close to the correct answer was statistically smaller than the percentage of those who provided a wrong answer. This result confirms our hypothesis about the existence of strong cognitive biases and of cognitive penetrability in the specific task, affirming our initial hypothesis (Hypothesis 1). At this point we must stress out that the most chosen option among the alternatives provided was the propositional representation: “whatever you cut gets separated into two new pieces.” The alternative option 5, according to which cutting the strip lengthwise will give two new strips of equal length but half the width of the original, gathered the highest percentage of answers (67.5%). The alternative answer 8 concerning one whole piece that participants couldn’t identify gathered 0%. This result supports the idea that participants used the propositional knowledge and didn’t put any effort in mentally manipulating the picture. We can also observe that among the 154 participants in the 2nd study, 137 (89%) chose between answers concerning 2 pieces and 17 participants (11%) chose between alternatives regarding 1 piece as a product of mental partitioning. This leads us to believe that prior established knowledge and not mental manipulation of images guided the majority of our sample in false answers regarding the mental partitioning task, making obvious the existence of cognitive biases guiding thought during this task's problem solving process – also confirming our first hypothesis.

Discussion – study 2From the results of the 2nd study, we conclude that there is a significant relationship between performance in spatial and mental partitioning tasks. Architecture students and participants below 25 years of age scored higher in both tasks. It seems that age and profession affects spatial reasoning competence. The task “Alternative solutions to Moebius strip mental partitioning” hints towards the use of propositional thought as well as the guidance of this task's representation by prior knowledge about the world. Specifically, whereas in the first task, success rate was 2.6%, when alternative answers were provided it doubled (5.2%). However, the success rate was still considerably low. A wide percentage of the answers provided (89%) revolved around the result of 2 separate pieces, leading us to believe that previous knowledge as to the nature of partitioning affected the participants’ answers. These results provide evidence that the ability to mentally partition an object is cognitively penetrable, but also indicate towards a strong cognitive bias that affected a high percentage of our sample. The most common option chosen amongst alternatives hints towards our initial hypothesis: our inner propositional representation that cutting an object leads to 2 new separate pieces will guide us towards the option: “two new strips our produced” which gathered 67.5% of the total answers. These results provide evidence regarding that most of the participants used their propositional knowledge while putting little to no effort in mentally manipulating the strip.

ConclusionsThe low rates of correct answers in the 2 studies (a total of 498 subjects, with only 2.6% of them finding the correct answer), for both participants who could see the strip as well as those who tried to mentally manipulate it, leads us to the conclusion that cognitive penetrability, as defined by Pylyshyn, guides mental transformation.6 We can also expand the idea of cognitive penetrability to perception. The large failure rate in the mental partitioning tasks supports the idea that some mental transformation problems are not facilitated by prior knowledge. The participants didn’t seem to manipulate the strip's mental image, and even if we accept that they manipulated it, the majority failed at the task. The basic principle of propositional representation is that words and images are represented in an abstract way that suggests the meaning and the use of knowledge.6 People encode and use all information (verbal and non verbal) in the form of propositional representations. When we want to use this information, we recall the corresponding propositional representation and use it for the appropriate tasks. The information: “Whatever you cut gets separated into 2 pieces” is a propositional unit that consists of two modules: 1st module=“Whateveryou cut” and 2nd module=“two pieces” are connected by the relationship of “gets separated into.” This rule seems to have affected the participants and validated Pylyshyn's views that mental images are guided by propositional cognitive cues (cognitive penetrability), at least regarding the task of the mental partitioning of Moebius strip. The participants had also difficulties in mentally manipulating the perceivable strip. They mustered available cognitive schemas (a simple collar) and tried to create semantic relationships between the old and new knowledge in order to understand and find the solution to the task at hand. Whatever the participants tried to manipulate, the Moebius strip task was affected by prior knowledge (the schema: “Whatever you cut, gets separated into two pieces”), which confirms Neisser's theory, and Shepard & Metzler's views, that people execute various mental tree – dimensional transformations, cannot be supported by this study's findings.13,14 The low success rates in the mental partitioning tasks lead us to the conclusion that the law of the least possible mental effort is true. People will use a spontaneous/fast way of thinking.15 The participants used a fast and spontaneous system of thinking, which works-based on associations, with little to no effort, without the use of self regulation, based on cognitive biases, with limited use of typical logic, and for that reason people came to false conclusions. According to our results, the independent variables “age,” “profession,” and “educational level” have an effect on spatial perception and mental partitioning tasks. The architecture students group and the “below 25” group scored the highest, and the psychology student group scored the lowest. The factor “educational level” affects only the spatial perception tasks and not the mental partitioning ones, with higher educational level participants scoring higher. Scores in spatial perception tasks are a predictor for performance in mental partitioning tasks and vice versa. The participants displayed a wide variety of cognitive behaviours during the tasks administered that hinted towards limitations of human thought. Their answers were a product of prior knowledge (biases), which prevented them from using possibly more effective solution methods. Scores in the main mental partitioning task showed that spatial reasoning is affected by what people know, and not by what they see or manipulate. These results lead us to support the idea that the process of mental partitioning a real object, rests on propositional representations and not on visual images. The participants’ thought was anchored in the idea that cutting an object leads to two separate pieces and prevented them from approaching the problem from a different perspective. In this specific partitioning sub-task, subjects sought a fast approach, that would connect their goal with available to them information. They used prior knowledge, on the basis that this would facilitate problem solving. People manipulating a Moebius strip seemed to “see what they know,” and not what “there is.” These findings support Pylyshyn's ideas, who supported the presence of specific conceptual – shaping processing. In particular the position that virtual processes are guided by cognitive propositional elements.6 It seems that a series of “up–down” information processes affect our perception, whereas our experiences create our internal theories and the way we perceive the world, at least in the case of visual – constructive transformation tasks (ex. Moebius strip's mental partitioning). The study of cognitive penetrability and the mental partitioning of mental and real objects, such as Moebius strip, constitute fertile ground for further inquiries in Cognitive science.

As the human brain has the ability to mentally simulate sensory information of not necessarily physically present stimuli, imagery mechanisms are fundamental to the computational functioning of the brain, facilitating predictive processing and guiding future behaviour. Our findings bring back to the scientific background the idea that the mind's selective attention to previous experience and cognitive schemas will decidedly affect human thought. The findings of the present research study also have implications for the field of psychopathology in general as well as suicidal ideation and the nosological entities of Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in particular, being associated with intrusive or uncontrolled distressing imagery (e.g., suicidal “flashforwards”).16 Dysfunctional imagery may also contribute to maladaptive interpersonal patterns. Furthermore, based on mental imagery, a capacity for higher-level metacognitive processing also exists. There are already known effective treatments and interventions targeting meta-cognition (such as rescripting the meaning of events and associated images/memories), the research of which has largely been neglected to date, despite their possibly powerful influence on altering patients’ conscious and unconscious behaviours.16 The present work, therefore, investigates a potentially valuable theoretical basis in imagery research for the understanding, and hopefully treatment of maladaptive imagery across various related clinical disorders, while encouraging multidisciplinary approaches among cognitive psychological/neuroscientific and clinical domains.

FundingThis work has not been funded by any corporation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The present research study pertains to the first author's doctoral dissertation/thesis with a National Documentation Center Code 43237.