Número especial: Avances y retos en la psiquiatría regional en Latinoamérica

Más datosThe study of behaviour is a fundamental part of comprehensive patient care, since the patient should be considered as a biopsychosocial entity. In the case of Alzheimer's disease (AD), the major limitation in the diagnosis of the patient is that it can only be made after death. Therefore, identification of behaviours consistent with behavioural dysfunction, psychosis and neuropsychiatric symptoms represents a very useful tool for establishing a presumptive diagnosis in vivo of AD. Further taking into account that diabetes mellitus (DM) is a disease with a growing worldwide incidence that is considered a risk factor for the development of AD, the presence of depressive behaviours and mild cognitive impairment stand out as important elements identified in the DM/AD link.

ResultsThis study presents the results of a review of evidence obtained from secondary sources and describes characteristic behaviours identified in AD.

ConclusionsWe conclude that the depressive behaviour identified in both AD and MD and the analysis of depressive behaviours along with mild cognitive impairment are part of the link between DM and AD.

El estudio del comportamiento es una parte fundamental de la atención integral del paciente, ya que se lo debe considerar como una entidad biopsicosocial. En el caso de la enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA), la mayor limitación para el diagnóstico del paciente es que solo puede hacerse post mórtem. Por lo tanto, la identificación de conductas relacionadas con disfunción conductual, psicosis y síntomas neuropsiquiátricos es un medio muy útil para establecer in vivo un diagnóstico presuntivo de EA. Teniendo en cuenta además que la diabetes mellitus (DM) es una enfermedad cuya incidencia en el mundo va en aumento y se la considera un factor de riesgo de EA, la presencia de conductas depresivas y el deterioro cognitivo leve destacan como elementos importantes identificados en el vínculo DM-EA.

ResultadosEn este trabajo se presentan los resultados de la revisión de la evidencia obtenida de fuentes secundarias, y se describen las conductas características identificadas en la EA.

ConclusionesSe concluye que la conducta depresiva identificada tanto en la EA como en la DM y el análisis de las conductas depresivas junto con el deterioro cognitivo leve son parte del vínculo entre la DM y la EA.

It is important to integrate the cognitive, emotional, motivational and social aspects of patients, considering that there is a bidirectional relationship between these aspects and diseases, since in each of these aspects may present predisposing factors for the development of various diseases, including dementia, reciprocally these aspects are affected by the diseases, therefore the comprehensive care of the patient involves giving equal attention to the cognitive, emotional, motivational and social manifestations as well as to the pathophysiological manifestations of the organism of each patient.1

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a chronic degenerative disorder whose accurate diagnosis is established through the analysis of postmortem brain tissue,2,3 which allows the identification of the three characteristic elements of such disease: β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide, hyperphosphorylated Tau protein (pTau) and neuroinflammatory biomarkers.4 This characteristic makes the opportune diagnosis of AD a multidisciplinary and multidimensional challenge, which has been approached by identifying the characteristic neuropsychiatric symptoms from the onset of the clinical stage.5 DM is an endocrine disease characterized by hyperglycemia associated with insulin resistance and impaired or absent insulin secretion.6

DM is considered a risk factor for AD7 with a clustered adjusted hazard ratio of 1.57,8 although such a link is still under study, however blood-brain barrier disruption and molecular mechanisms in common, especially alterations in glucose metabolism and insulin receptors, as well as neuroinflammation and manifestations such as cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression that occur in both AD and DM.9

Cognitive impairment consists of altered cognitive abilities leading to variable impairment of functional and instrumental skills.10

Neuropsychiatric symptoms refer to the alterations perceived by the patient or his caregivers, these have been classified into subsyndromes consisting of alterations such as hyperactivity, psychosis, and mood disorders. Within the hyperactivity group we find aggression, disinhibition, irritability, aberrant motor behavior and euphoria. In psychosis, delirium, hallucinations, and sleep disorders. Finally, mood disorders include depression, anxiety, apathy and eating disorders.11

Neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety share characteristics with psychiatric diseases of the same name but differ mainly in their etiology because they are linked to a specific neurodegenerative condition or neurological damage process. In these cases, neuropsychiatric symptoms are considered “analogues of idiopathic psychiatric diseases considering the similarities of their manifestations.” Therefore, the approach to these should be different, and we should conceive them as homonymous entities that require different approaches.12 This delineation is important considering the role of neuropsychiatric symptoms as early indicators of a stage prior to the development of dementia or indicators of the severity of the neurodegenerative condition based on its characteristics. For example, in the case of depression as an initial neuropsychiatric symptom identified in a cohort of older adults, the incidence rate of dementia was estimated at 44.9 with a relative risk of 1.6 (95% confidence interval [95%CI], 1.2-2.3) over 3 years of follow-u0p.13 In another study depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom presented a strong positive association of OR=1.64 (95%CI, 1.49-1.81) with the development of dementia.14

Depression is one of the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms identified in subjects with AD-type dementia and in states prior to the development of dementia such as mild cognitive impairment.15 It is also one of the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in DM.16

This paper addresses the behavioral alterations or neuropsychiatric symptoms that occur specifically in subjects with AD, followed by a description of the depressive symptom developed in subjects with DM, and then highlights the alterations that both AD and DM have in common in terms of the development of cognitive impairment and through this the development of depression, proposing in turn the succession of events that could lead from DM to AD through the neuropsychiatric symptom of depression.

DM-AD linkThe relative risk of progression from DM to dementia is 1.9 [1.3-2.8], of which those with more impaired carbohydrate metabolism in insulin-requiring DM phase have a relative risk of 4.3 [1.7-10.5], specifically the risk of progression to AD type dementia is 1.9 [1.2-3.1].17

Having DM2 represents an independent risk factor for depression (OR=2.04; 95%CI, 1.71-2.38) in subjects with early-stage AD18.

Several studies have investigated the DM-EA link identifying multiple common alterations between both diseases from molecular to clinical manifestations,9 being cognitive impairment one of the common manifestations present in both diseases; with respect to AD cognitive impairment is considered a preamble in AD subjects, i.e. a phase prior to the development of the disease in which some neuropsychiatric symptoms begin to present among which depression is one of the most frequent.15

Meanwhile cognitive impairment occurs progressively in subjects with DM with a positive relationship between the time of disease progression and hyperglycemia, characterized by impairment of memory and measures of attention, information processing and executive functioning; the last one linked to mental and motor retardation.19 Some studies further propose that cognitive impairment modulates the characteristics of neuropsychiatric symptoms that develop, so that cognitive impairment is a common phase in both AD and DM that should be given special attention based on the study of neuropsychiatric symptoms that both diseases may present.10

ResultsBehavioral alterations in Alzheimer's diseaseLongitudinal studies have evaluated the variability of the development and manifestation of neuropsychiatric symptoms according to the years of AD evolution, highlighting that depression and apathy are significantly present in both early and advanced stages.20

In the following, we address the neuropsychiatric symptoms that make up the mood subsyndrome, to which both depression and apathy belong together with anxiety and eating disorders, of the other two subsyndromes we only address sleep disturbances and aggressiveness as the neuropsychiatric symptoms, representative of the psychosis and hyperactivity subsyndromes respectively.

AggressivenessAggressiveness, together with the other symptoms of hyperactivity subsyndrome, represent a marked detriment for both the patient and his or her family, relatives and caregiver, considerably reducing the quality of life, mainly in the social and family environment, and increasing the probability of institutionalization of the patient.21

In turn, the wearing down of the caregiver-patient relationship that on many occasions derives in institutionalization impacts on the patient's conditions favoring and aggravating the development of aggressiveness and other neuropsychiatric symptoms, which is why it has been established that there is a bidirectional relationship between the patient-caregiver relationship and the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms.22

Some of the characteristics that both patients and their caregivers often refer to aggression are verbal insults, shouting, hitting, biting, or throwing objects.23 Clinically, it is possible to detect and size aggressive behavior through the Overt Aggression Scale (OAS).21

Although multiple anatomical patterns of brain involvement linked to the development of the different symptoms that compose the hyperarousal subsyndrome have been described, they all coincide in the reduction of neurotransmission through the far-reaching monoaminergic pathways of the corticostriatal circuit.21

Specifically in AD subjects the development of aggressiveness is attributed to the involvement of brain regions such as the left anterior temporal, bilateral dorsofrontal and right parietal cortex due to decreased perfusion; in the left insula, bilateral anterior cingulate cortex, bilateral retrosplenial cortex and left middle frontal cortex due to decreased gray matter volume; in the inferior anterior cingulate due to evidence of fractional anisotropy; in the frontal cortex, insula, amygdala, cingulum and hippocampus due to atrophy; and in areas such as the right anterior cingulate cortex and right insula due to increased connectivity (corrected atrophy).24

Molecularly the symptom of aggressiveness is attributed to decreased serotonin and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA); decreased Brodmann's area 10 and 20 cholinergic markers such as choline acetyltransferase and acetylcholinesterase; increased pS396 tau in Brodmann's area 9.24 Thus it has also been observed that increased pTau/Tau ratio values at the level of the frontal cortex in AD patients favor the development of aggressiveness.25,26 Added to this the increased bioactivity of tau aggregates composed mainly of the soluble high molecular weight (HMW) species, favor the development of aggressive behavior at younger ages.27 In contrast, a negative correlation has been observed between levels of the Abeta42 subtype of Aβ in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the development of aggressive behavior in AD patients.27

The genetic overview indicates that the 5-HTTPR 1 polymorphism of the SLC6A4 gene where the promoter region of the serotonin transporter is located; the 102T/C polymorphism of the serotonin receptor 5-HT2A gene;26 the biallelic polymorphism in intron 7 of the gene on chromosome 11 encoding tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) in males;26 and the DRD1 B2 polymorphism of the dopamine receptor gene increase the risk of aggressive behavior in subjects with AD.26 So also, analysis and comparison of DNA/mRNA transcriptomic arrays, candidate gene association studies (CGAS) and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) highlights that androgen receptor (AR; chrXq12), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; chr11p14.1), catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT; chr22q11. 21), neuronal specific nitric oxide synthase (NOS1; chr12q24.22), dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH chr9q34.2) and tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH1, chr11p15.1 and TPH2, chr12q21.1 are coincidentally implicated in AD and aggressive behavior suggesting new pathways that allow explaining the development and characteristics of aggressiveness in AD patient.28

Sleep disturbancesSleep behavioral disturbances in patients with AD are difficulty falling asleep, repeated nocturnal awakenings, early morning awakenings and excessive daytime sleepiness, depending on the intensity of the manifestations the patient may present disorders derived from these disturbances, such as: insomnia, sleep-wake cycle disorders (delay or advance of the sleep-wake cycle) and circadian rhythm, sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD) and sleep-related movement disorders.29 Clinical identification of these disturbances is supported by tools such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire, and the Athens Insomnia Scale.30

Sleep disturbances can occur from the stage prior to AD development known as mild cognitive impairment and worsen as the disease progresses,31 which is consistent with the nocturnal decrease in CSF melatonin levels from preclinical stages of AD, therefore it has been proposed as a biomarker of AD.32

The role of melatonin goes beyond being a biomarker since this neurohormone participates in physiological conditions in the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle and reciprocally the alterations of the sleep-wake cycle impact on the release of melatonin.33 It is considered that melatonin may represent an alternative treatment for sleep disturbances in AD, since it appears to have chronobiotic and cytoprotective properties. Among the effects evaluated, decreased sleep latency and increased sleep duration were considered, which appear to be both dose-dependent and time-dependent; however, formal implementation of this element as a treatment for AD requires further testing.34

Regarding AD the administration of melatonin in animal models negatively impacts pTau production through PI3K/Akt/GSK3β signaling; it also decreases Aβ generation and inhibits the initial phases of Aβ aggregation, specifically up to the nucleation phase and does not reverse oligomers or fibrils once they are formed.34 Precisely the increased accumulation of Aβ is considered the main point of the bidirectional synergistic relationship between sleep behavioral alterations and AD.30

For example, a longer sleep latency is related to Aβ accumulation in prefrontal cortexes including the anterior cingulate cortex; whereas in those with shorter sleep latencies the accumulation of occurs mainly in precuneus, angular gyrus and medial frontal orbital cortex and in those with fractionated sleep patterns Aβ deposition occurs mainly in the insular region, angular gyrus, medial frontal orbital cortex, cingulate gyrus and precuneus.35

There is a link between sleep disturbances and alterations in eating behavior in subjects with AD attributed to increased deposition of β-amyloid peptide, pTau protein, and markers of neuroinflammation in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, a region in which neuropeptide orexigenic peptide neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti gene-related peptide (AgRP), involved in sleep regulation and satiety processing, respectively, are synthesized.34

Nutritional alterationsEating disturbances occur in 81.4% of patients with AD and specifically in those in early stages of the disease they occur in 49.5% of cases indicating that it is a frequent neuropsychiatric symptom.36 As AD progresses to more severe stages the rates of eating disturbance also increase.36 Feeding disturbances increase the risk of malnutrition in patients with dementia mainly when associated with other risk factors such as advanced age, cognitive impairment, and institutionalization.37

Clinical screening for eating disturbances in patients with dementia is established from five main domains: swallowing problems, appetite changes, food preference, eating habits and other oral behaviors.36 Of these items swallowing problems such as difficulty swallowing food, difficulty swallowing liquids, coughing or choking while swallowing, prolonged swallowing process, putting food in the mouth but not chewing it or chewing food but not swallowing it; have been identified more frequently in AD subjects from early stages compared to other types of dementia.36

Appetite changes identified through manifestations such as: decreased or loss of appetite, increased appetite, seeking food outside of their feeding times, overeating at feeding time, requesting more food, reporting unwarranted hunger, reporting unwarranted satiety; caregiver's need to limit the food ingested by the patient, are present in 49.5% of early stage AD cases and 77.6% of late stage AD subjects.36

Next the alterations in food preference characterized by: increased preference for sweet foods, increased preference for sweet drinks, increased intake of beverages such as tea/coffee or water, patient's reference that “the taste of food has changed” (reference of alterations in taste perception), adding more condiments to their food, developing other food fads, food hoarding, starting or increasing alcohol intake; are present in 36.4% of cases with early-stage AD and in 46.6% of cases with late-stage AD.36 Appetite changes characterized by increased food intake; are attributed to decreased density of serotonergic 5-HT4-type serotonergic receptors in AD patients.38

AnxietyAnxiety in conjunction with depression, irritability and apathy are considered mild neuropsychiatric symptoms;12 the overall prevalence of this is 39% predominantly in the early stages of AD.39 Higher scores on the hospital scale of self-rated anxiety and depression are attributed to decreases in the volume of subcortical structures such as the amygdala and caudate nucleus and increased Aβ deposition identified by scanning 18F-flutemethamol uptake in brain regions such as the precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, prefrontal cortex, parietal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex.40 In turn the presence of anxiety in AD subjects was characterized by increased brain activity in the temporal and parietal regions identified characterized by increased complexity of the EEG.41

Apathy and depressionApathy is one of the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms being the main symptom detected in subjects with early-stage AD with a prevalence of 48.3% and 68.5% in subjects with AD in more advanced stages.42 In parallel, the incidence of depression in AD patients is 53% according to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH-Dad) criteria and 47% according to the International Classification for Diseases (ICD-10) criteria, reflecting that the sensitivity of tests for the identification of this neuropsychiatric symptom is variable. Despite this variability and regardless of the criteria applied, the incidence of depression in patients with AD proves significant mainly in the early stages of AD.42

Apathy consists of lack of initiative (directed behavior), lack of interest (cognitive activity), and emotional blunting, which can manifest through the subject's own goal-directed behavior and manifestations of interest, goal-directed cognitive activity, and spontaneous or reactive emotional expression.43

Whereas manifestations of depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom involve complaints of sadness, dysphoria, suicidal tendencies, decreased psychomotor activity, social withdrawal, anhedonia, decreased displays of interest, hopelessness, guilt, sleep disturbances, and changes in eating,44 it is common for both neuropsychiatric symptoms to be mistaken for each other, especially if the manifestations are decreased manifestations of interest or decreased psychomotor activity and social withdrawal that in certain contexts may resemble lack of initiative or lack of interest and emotional blunting.45

However, to delimit both cases, tools have been designed to allow the identification and sizing of the severity of apathy among which are the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES), Apathy Inventory (AI) and Lille Apathy Scale,24 as well as tools for the identification and measurement of depression severity are the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia and National Institute of Mental Health Interim Diagnostic Criteria for Depression in Alzheimer's Disease (NIMH-dAD).46

The anatomical regions implicated in the development of apathy in AD subjects are the anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex and subcortical structures such as the ventral striatum, medial thalamus and some temporal regions whose metabolism assessed through fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) was observed decreased; in turn, evaluation by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) showed reduced perfusion in cortical regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex, the frontopolar cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Some of the regions affected by decreased gray matter volume are the anterior cingulate and dorsolateral prefrontal cortexes, and subcortical structures such as the putamen, caudate nucleus,43 amygdala, hippocampus and nucleus accumbens and to a lesser extent globus pallidus and thalamus.40 In turn, evaluation of the left anterior and posterior cingulate, right superior longitudinal fasciculus, bilateral uncinate fasciculus and internal capsule of the corpus callosum evidenced decreased white matter integrity in these tracts due to fractional anisotropy.47

Further assessments of white matter status consisting of the automated segmentation method using a lesion prediction algorithm and evaluation by visual classification of FLAIR images according to the Age-Related White Matter Change (ARWMC) scale resulted in lesions in the white matter of the frontal cortex and to a lesser extent in the temporal and occipital parietal cortexes.40

Regarding the areas affected by Aβ deposition identified through positron emission tomography, the orbitofrontal cortex, right anterior cingulate cingulate cortex, insula47and the precuneus, and to a lesser extent the posterior cingulate cortex, occipital cortex, prefrontal cortex, sensorimotor cortex, parietal cortex and lateral temporal cortex.40

Regarding the anatomical structures involved in depressive manifestations in AD subjects, the decrease in the volume of the left medial frontal cortex48 and the left inferior temporal gyrus49 stand out. In turn, in subjects with AD and depressive symptoms who participated in MRI evaluations for the establishment of conditional growth models, it has been observed that the greater the severity of depressive symptoms the greater the rate of thinning of the anterior cingulate cortex, additionally it was identified that if depression is of early manifestations there is an accelerated atrophy of the anterior cingulate cortex only in the left hemisphere and of the entorhinal cortex of the right hemisphere.24 Other regions that have evidenced cortical thinning are the left dorsolateral prefrontal, left anterior temporal and left inferior temporal cortex.50

Considering cortical involvement in conjunction with subcortical alterations such as gaps in the basal ganglia of the right hemisphere,51 among which the caudate nucleus and lentiform nucleus stand out, the fronto-striatal hypothesis of depression in AD has been proposed.52

In parallel, the theory of disruption of fronto-subcortical brain pathways has been proposed as the origin of depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom in AD.52 Such a theory is supported by increased medial diffusivity and radial diffusivity in the cingulate gyrus of both hemispheres and in the uncinate fasciculus of the right hemisphere implying microstructural abnormalities in the white matter of 2 of the main fronto-limbic connecting pathways in AD patients presenting with depressive symptoms.53 In reinforcement of this position, it has also been observed that subjects with AD and depressive symptoms present significantly decreased values of functional connectivity in the right middle temporal gyrus and right superior temporal gyrus. This evidence further suggests the importance of alterations in hypothalamic intrinsic connectivity in the establishment of depressive symptoms in AD subjects.54

Regarding blood flow alterations, the decrease in blood flow in the left hemisphere medial frontal gyrus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex55 stands out. Additionally, when evaluating the cerebral glucose metabolic rate in patients with AD and depressive symptoms, hypometabolism was evidenced in the superior frontal gyrus and middle frontal gyrus of both hemispheres as well as hypometabolism in the anterior cingulate gyrus predominantly in the left hemisphere, hypometabolism in inferior frontal gyrus predominantly in the right hemisphere,12 hypometabolism in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, postcentral gyrus and superior and inferior lobe.12 When assessing metabolic rate in subjects at the stage of mild cognitive impairment with detection of Aβ deposits by positron emission tomography, hypometabolism was found in the precuneus, angular gyrus and middle temporal gyrus of the right hemisphere, as well as hypometabolism in the inferior temporal gyrus of the left hemisphere.56

Another significant alteration in patients with AD and depressive symptoms is the decrease in the number of neurons in the medial levels of the locus coeruleus and the upper central portion of the raphe nuclei.57 Giving rise to the formulation of hypotheses that attempt to explain the depressive manifestations in AD subjects, being the deficiency of monoamines such as serotonin (from the raphe nuclei) or noradrenaline (from the locus coeruleus) some of these hypotheses.58

In support of the serotonergic hypothesis, it has been observed that impairment of the serotonergic system occurs in the early stages of AD being this period the one with the highest incidence of the development of depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom in AD patients.58 So also that intracerebroventricular administration of Aβ to rats induces depressive manifestations (increased frequency in immobility behavior and reduced swimming frequency) along with decreased serotonin levels in the prefrontal cortex being this one of the brain areas whose metabolism and volume are affected in patients with AD and depressive symptoms.58 In turn AD patients with comorbid depression or a history of major depression have a higher burden of amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in their brains than AD patients without depression.52 In another double transgenic mouse model of early AD when administering the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine, which also serves as an antidepressant; a decrease in the loss of neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus and a decrease in Aβ deposition was observed, correlated with improvement in spatial learning, additionally a significant inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 type β (GSK3β) activity was observed.59

Deepening the serotonergic hypothesis suggests that glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) activity is responsible for regulating serotonin activity in neurotransmitter processes as decreased levels of this neurotransmitter result in increased GSK3 activity. In turn, the influence of GSK3 in subjects with AD and depression has been suggested from the observation of a decrease of inactivated GSK3 in platelets of subjects with both conditions.52

It is pertinent to mention that GSK3β is one of the major kinases involved in Tau phosphorylation and hyperphosphorylation in AD.60 GSK3 also participates in multiple cascades specific to physiological and pathological processes through its two isoforms GSK3α and GSK3β, to assess the influence of hyperactivity of both isoforms we used GSK3α 21A/21A knockin and GSK3β 9A/9A knockin mouse models, observing that abnormally active GSK3β increases susceptibility to the learned helplessness model, an indicator of hypoactivity as a depressive symptom, assessment of novel object recognition showed that the discrimination index was impaired in GSK3β knockin mice (one-way ANOVA, F(2.31)=5.043); in this group, a severe impairment of hippocampal neural precursor cell proliferation was also observed (727±185; one-way ANOVA, F(2,19)=31.93; P<.01), reaching 18% of the proliferation observed in control mice.61 GSK-3α silencing in AD-like transgenic mouse models led to decreased senile plaques, phosphorylation and misfolding of Tau and improved memory capacity, whereas GSK-3β silencing led to decreased phosphorylation and misfolding of Tau.62

Regarding the noradrenergic hypothesis, decreased levels of noradrenaline in the neocortex and allocortex have been observed in AD patients with depressive symptoms.52

Other alterations characterizing depressive manifestations in AD subjects are lower N-acetylaspartate/creatine (NAA/Cr) gradient and higher myoinositol/creatine (mI/Cr) gradient at the level of the left anterior cingulate gyrus identified through proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS), suggesting decreased neuronal density or decreased neuronal metabolism and increased glial cell activity.49

Additionally, in AD subjects with depressive symptoms a decrease in gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) has been observed coexisting with an increase in the number of GABAergic receptors, as for the severity of depressive symptoms in AD this correlates with a decrease in the density of the serotonergic transporter 5-HTT.12 The decrease of GABA in subjects with AD and depressive symptoms has been identified mainly in the neocortical region, additionally a decrease of the glutamate/GABA ratio has been identified which further suggests evaluating the role of glutamate in this process.52

The relationship of the glutamatergic system with depression and depressive manifestations has gained increasing interest considering that NMDA-type glutamatergic receptor antagonist drugs such as ketamine exhibit antidepressant properties, even being proposed as a treatment for idiopathic depression.63

In 2014 Horning postulated that the development of depression, anxiety and apathy is mainly due to the patient becoming aware of their illness, however, this hypothesis remains highly controversial considering the multidimensionality of the diseases, as social and cultural variables play an important and complex role in the perception of the concept of “illness” and translating into a spectrum of behavioral manifestations that varies in each individual. Therefore, the consensus of appropriate measurement tools for this phenomenon represents a challenge to achieve the verification of such hypothesis.64

On the other hand, Novais rejects this hypothesis, arguing that multiple studies provide information that indeed the psychic processes of personification and protagonization of the disease are strongly intertwined with behavioral alterations in chronic diseases such as AD; however, he emphasizes that these are anosognosia and dysthymia and not depression or apathy. Nevertheless, both Horning and Novais agree that improvements and standardization of assessment methods are required in order to determine whether this hypothesis is definitively accepted or rejected.64

Considering the evidence of the organic alterations associated with apathy and depression, it is difficult to accept Horning's hypothesis; although the fact that the patient becomes aware of his illness is not the cause of the development of these neuropsychiatric symptoms, it would be worth exploring it as a factor that influences the progression of the development of these and other neuropsychiatric symptoms.

It has been observed that the downregulated expression of miR-484, miR-197-3p, miR-26b-5p and miR-30d-5p is associated with the presence of depressive symptoms, and it is noteworthy that the downregulated expression of miR-484 and miR-197-3p has been linked to the more accelerated progression of cognitive impairment towards dementia. Specifically down-expression of miR-484 in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) was significantly associated with greater depressive symptoms and progression to AD.65

Neuropsychiatric depressive symptoms in diabetes mellitusDepressive symptoms in DM are characterized by sadness (1.4±0.9 vs. 0.9±0.9; P=.011), difficulty concentrating (1.3±0.8 vs. 0.8±0.8; P=.01), indecisiveness (1.1±0.8 vs. 0.5±0.9; P=.012), health concerns (1.3±0.9 vs. 0.6±0.9; P<.0001), fatigue (1.2±0.6 vs. 0.8±0.7; P=.003) and loss of sexual appetite (2.7±0.6 vs. 1.2±1.3; P=.0001).66 Other studies refer to the presence of anhedonia and suicidal ideation in subjects with DM however these symptoms mainly point to idiopathic depressive disorder.66

Depressive symptoms are common in patients with DM.67,68 The relative risk of depression incidence in subjects with diabetes mellitus has been estimated to be 1.27 (95%CI, 1.17-1.38), while the hazard ratio is 1.23 (95%CI, 1.08-1.40), both values are significant and indicate that diabetes mellitus conditions favor the development of depression.69 Considering both adolescent and adult population with DM, the incidence of depressive symptoms is estimated at 40.5%.67,70 The annual incidence of developing depression in subjects with DM without previous depression is estimated to be 1.2% (95%CI, 1.11%-2.81%).71

It is important to consider that a correlation has been evidenced between hyperglycemia, increased GABA and cognitive impairment in patients with DM, which provides evidence to defend the idea that these neurotransmitters have a relevant role in the process of cognitive impairment linked to hyperglycemia, in turn GABA is a neurotransmitter involved in an important way in the depressive process.72 An interesting fact considering the growing evidence linking the influence of GABA in the development and management of depression, leaving the door open to investigate the relationship of this neurotransmitter with the development and treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of depressive type.73

Considering the increased probability of developing depression according to the duration of DM and that the higher incidence of depression occurs in patients with diagnosed diabetes compared to subjects with prediabetes and undiagnosed diabetes has suggested the influence of the psychological burden of recognizing oneself sick as proposed by Horning's hypothesis; however, it is not left out that the organic component, mainly the impaired glucose metabolism, which is different in each study group due to being in different stages of disease progression.71

Because the incidence of depression in subjects with DM is significant, coupled with the fact that subjects with depression have a 25-60% risk of developing DM, in conjunction with the synergistic influence of DM-depression comorbidity, on the development and severity of both entities, it has been proposed that there is a bidirectional relationship between DM and depression.74 However, it should be recognized that so far several of the studies that inquire into this bidirectional relationship and especially those that focus on cases of depression developed after the establishment of DM, do not establish the difference between depression as an idiopathic disease and depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom.74

The study of the cerebral repercussions of DM has been deepened by finding temporal lobe sclerosis, decrease in global brain volume associated with cortical atrophy due to significant loss of neocortical neurons (38±2×106 vs. 46±3 × 106), decrease in the length of the capillary network in neocortical tissue75 decreased white matter volume in the parahippocampal gyrus, temporal and frontal lobes, as well as decreased gray matter volumes and densities of the thalamus, hippocampus, insular cortex, superior and medial temporal and frontal gyri,76 as well as decreased projections from the medial amygdala to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and medial preoptic area, which may be associated with the anhedonia observed in animal models of DM and depression in humans.77

At the basic research level, the rat model of DM presents depressive symptoms associated with lower rates of proliferation and differentiation of neuronal progenitor cells (neurogenesis) and survival of neurons.78 In the adult stage mammalian brain, neurogenesis is mainly detected in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricle and the subgranular region of the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus, the latter being an important region in learning and memory processes, frequently affected in DM models.79 Mainly at the level of CA3 due to increased expression and activity of Caspase-3, and apoptotic gene regulators.76

The manifestations of depressive symptoms in the DM rat animal model are anhedonia80 and hypoactivity,80 attributed to impaired spatial learning and memory, which in humans could translate as cognitive impairment.81 The affectation of neurogenesis and survival of hippocampal neurons starts from stages prior to DM such as prediabetes;82 this is reasonable considering that there are conditions in common between diabetes and prediabetes such as hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, impairment of the insulin/PI3K/Akt/GSK3 pathway, oxidative stress and chronic low-grade inflammation which have also been linked to hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis dysregulation, decreased neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation.78

In patients with DM, a flattening of the diurnal cortisol curve has been observed, mainly attributed to the elevation of cortisol levels at night, a state called subclinical hypercortisolism.83 The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is responsible for the regulation of secreted levels of the hormone cortisol whose systemic release is cyclic obeying a curve pattern whose slope is located between 6:00 and 11:00 am, in the case of subclinical hypercortisolism present in patients with DM the release pattern of this hormone is different.84 Linking to higher blood glucose levels and insulin resistance in patients with DM because cortisol at the hepatic level promotes gluconeogenesis and decreases glycogen synthesis, simultaneously in muscle cells decrease glucose uptake by increased release of fatty acids that interfere with insulin signaling,85 causing a loop from hyperglycemia to dysregulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and back through increased cortisol release.83

Understanding how DM leads to this increased cortisol release requires considering that conditions of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in a rat model of DM induced by HFD and streptozotocin (HFD/STZ) administration caused an increase in the number of FosB-positive cells in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (207±31 vs. 139±22; P<.05), supraoptic nucleus (SON) (32±5 vs. 19±4; P<.05), subfornical organ (SFO) (114±10 vs. 67±15; P<.05) and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) (50±10 vs. 23±9; P<.05), suggesting chronic neuronal activation in those regions of the hypothalamus.86 Consistent with this evidence, in another rat model of streptozotocin-induced DM, significantly high levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) mRNA (P<.01) were observed throughout the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), with the highest abundance in the medial parvocellular region.87 Adding to this evidence in the (HFD/STZ) model, increased 24h urinary noradrenaline levels and increased renal sympathetic nerve activity were also reported,86 as well as increased cortisol levels detected in DM patients.83

The progression of hypercortisolism to the development of depressive symptoms has been proposed from the observation of the high prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder (50-81%) and neuropsychiatric symptoms including depression, in patients with Cushing's syndrome.84 Various brain structures possess an abundance of both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors in neurons, glial and vascular endothelial cells; while mineralocorticoid receptors are abundantly expressed in limbic neurons, mainly in the hippocampus, lateral septum and amygdala, glucocorticoid receptors have a wider distribution, being expressed both in limbic areas and in typical stress regulation centers, such as the PVN, the prefrontal cortex-hippocampus-amygdala circuit, ascending aminergic neural networks and the pituitary gland. This allows glucocorticoids to participate in both cognitive and emotional processes.88 There are four theories that purport to explain the mechanisms through which glucocorticoids cause alterations at the level of the central nervous system; the first proposes that decreased glucose uptake and metabolism in brain cells causes damage and death of these cells leading to atrophy of the affected areas; the second theory points to excitotoxicity resulting from increased release of excitatory amino acids such as glutamate in response to glucocorticoid signaling; the third theory points to inhibition of “long-term potentiation” resulting from reduced synthesis of neurotrophic factors important in cognitive processes such as learning and memory as well as cell survival; the last hypothesis emphasizes suppression of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus supported by findings of atrophy in this structure in cases of hypercortisolism.89 Despite the various theories it should be noted that hippocampal involvement and mainly atrophy of the prefrontal cortex or suppression of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus are considered important for the development of depression, conditions also observed in DM subjects and models.78

Recent evidence points to hypoglycemic drug administration and glycemic control decreasing adrenocorticotropic hormone levels and manifestations of depressive symptoms, reinforcing the relationship between pathological conditions of DM and the development of depression.90

The effects of insulin resistance evaluated through a specific knockout model of the brain insulin receptor (NIRKO mice), presented reduced mitochondrial oxidative activity with consequent mitochondrial dysfunction, increased levels of reactive oxygen species and as well as lipid and protein oxidation, in addition to this, the NIRKO models presented an increase of 31±13% in immobility time during a tail suspension test, considered an indicator of depressive behavior corresponding to hypoactivity.91 Complementarily when evaluating the effects of insulin resistance in astrocytes in the astrocyte insulin receptor specific knockout model (GIRKO mice), depressive behaviors such as anhedonia were observed by sucrose preference test and hypoactivity by forced swimming test.92 In a high-fat diet (HFD) Wistar rat model of insulin resistance, depressive behaviors such as anhedonia by sucrose preference test and hypoactivity by forced swim test were observed, added to these findings the model exhibited decreased proliferation and serotonin sensitivity, insulin and leptin in hippocampal dentate gyrus neurons, linked to a lower concentration of phosphorylated GSK3β (pGSK3β), i.e. in its inactive state, which is due to decreased signaling of the PI3K/Akt/ GSK3β insulin pathway.93

The relevance of GSK3 in diabetes further derives from its involvement in glucose metabolism as part of the insulin/PI3K/Akt/GSK3 pathway, when insulin resistance develops downstream signaling is disrupted so that Akt does not phosphorylate GSK3 and this then remains active, for insulin signaling to continue through this pathway GSK3 β must be phosphorylated to be pGSK3β.94 In another STZ-induced DM rat model, decreased levels of pGSK3β along with its upstream inhibitor Akt were observed as part of the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway.95 It is considered that GSK3β could affect neuronal survival as it is also involved in the regulation of apoptosis; against conditions characteristic of DM such as oxidative stress or inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway the intrinsic apoptosis pathway is activated and in which GSK3β plays a proapoptotic role linked to the activation of caspase 3.96,97

It should be considered that neurological damage in subjects with DM is also due to the conditions of oxidative stress and chronic low-grade inflammation that characterize this disease, since hyperglycemia activates multiple alternative metabolic pathways such as the polyol pathway, the protein kinase c (PKC) pathway, the advanced glycation end products (AGE) pathway and the hexosamine pathway through which increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to a state of oxidative stress, such conditions in turn activate transcription factors such as nuclear factor kappa enhancer of B cells (NF- κB) and specialty protein-1 (SP-1), promoting synaptic and neuronal alterations, increased cerebral microvascular permeability and neuroinflammation, conditions that when they become chronic lead to brain cell dysfunction and apoptosis.98 In the Insulin receptor substrate-2 (IRS2/) deficient mice model, increased levels of proinflammatory markers were observed in the hypothalamus, mainly tumor necrosis factor (TNF), NF-κB and JNK as well as indicators of oxidative stress such as Nox-4 and catalase, in conjunction with increased cell death linked to caspase-3 and caspase-8 activation.99

This inflammatory phenomenon in the hypothalamus in turn causes decreased sensitivity of the hypothalamus to insulin and leptin promoting hyperphagia, weight gain and affecting peripheral glucose metabolism.100 Regarding the hypothalamic inflammation phenomenon, the evidence is inconclusive as to which event occurs first, DM or hypothalamic inflammation as both show a bidirectional relationship, added to the observation that prediabetes models develop hippocampal inflammation and subsequently progress to DM.100

From the genetic perspective, modifications in the regulation of modified found RNAs between subjects with DM and subjects with DM and depression have also been evaluated highlighting the down-regulation of mRNAs such as ORMDL3 and UBC and up-regulation of mRNAs such as OR2W3, CCR7, RPS4X, ANKHD1-EIF4EBP3, NELL2, CDC25B, HIST1H3J, SLC7A6, SMIM3 and CD27, the latter being also found up-regulated in patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Some non-coding RNA types also evaluated in this study have been circRNAs observing that subjects with DM and depression unlike subjects with DM had up-regulated TFRCs, ZNF337-AS1, TNIK, HMMR, CCNB1, SI1, CUL4A, ASXL2, YAF2, LUC7L3 as well as down-regulation of TXLNG2P, DDX3Y, ZFY, CLK4, CHPT1, ZNF833P, SYNE1, CCS, RNF10 and CTPS1. We complementarily evaluated the differential expression of lncRNAs in subjects with DM and depression compared to subjects with DM finding that lncRNAs XIST, RP11-706O15.3, RP11-706O15.5, RP11-415F23. 2, RP11-1250I15.1, CTC-523E23.11, RP11-706O15.7, AL122127.25, TNRC6C-AS1 and RP4-575N6.4 were found to be up-regulated while lncRNAs AP000350.5, MIF-AS1 and RP11-51J9.5 were found to be down-regulated.101 Performing a CNC network analysis highlighted the role of lncRNAs ENSG00000271964.1_2 and ENSG00000279995.1_2, the former being associated with CD27, CCR7, NELL2 and EPPK1 mRNAs while ENSG00000279995.1_2 was positively correlated with DDX11 in subjects with the DM-depression duplex.101

Regarding the approach to pharmacological treatments for DM that impact depressive symptoms, the administration of hypoglycemic drugs such as metformin,102 liraglutide,90 roziglitazone,103,104 and intranasal insulin treatments restores the proliferation rate, differentiation and survival of hippocampal cells and reverses manifestations of depression, although such effects depend on therapeutic interventions being performed at early stages.78

Depression and cognitive impairment within the DM-AD linkageThe development of depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom linked to cognitive impairment in both DM and AD coincides in both diseases with respect to the involvement of structures such as the prefrontal cortex and dentate gyrus, the mechanism of damage coincides in decreased volume of the cortex by atrophy and decreased blood flow to it and decreased neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus.78

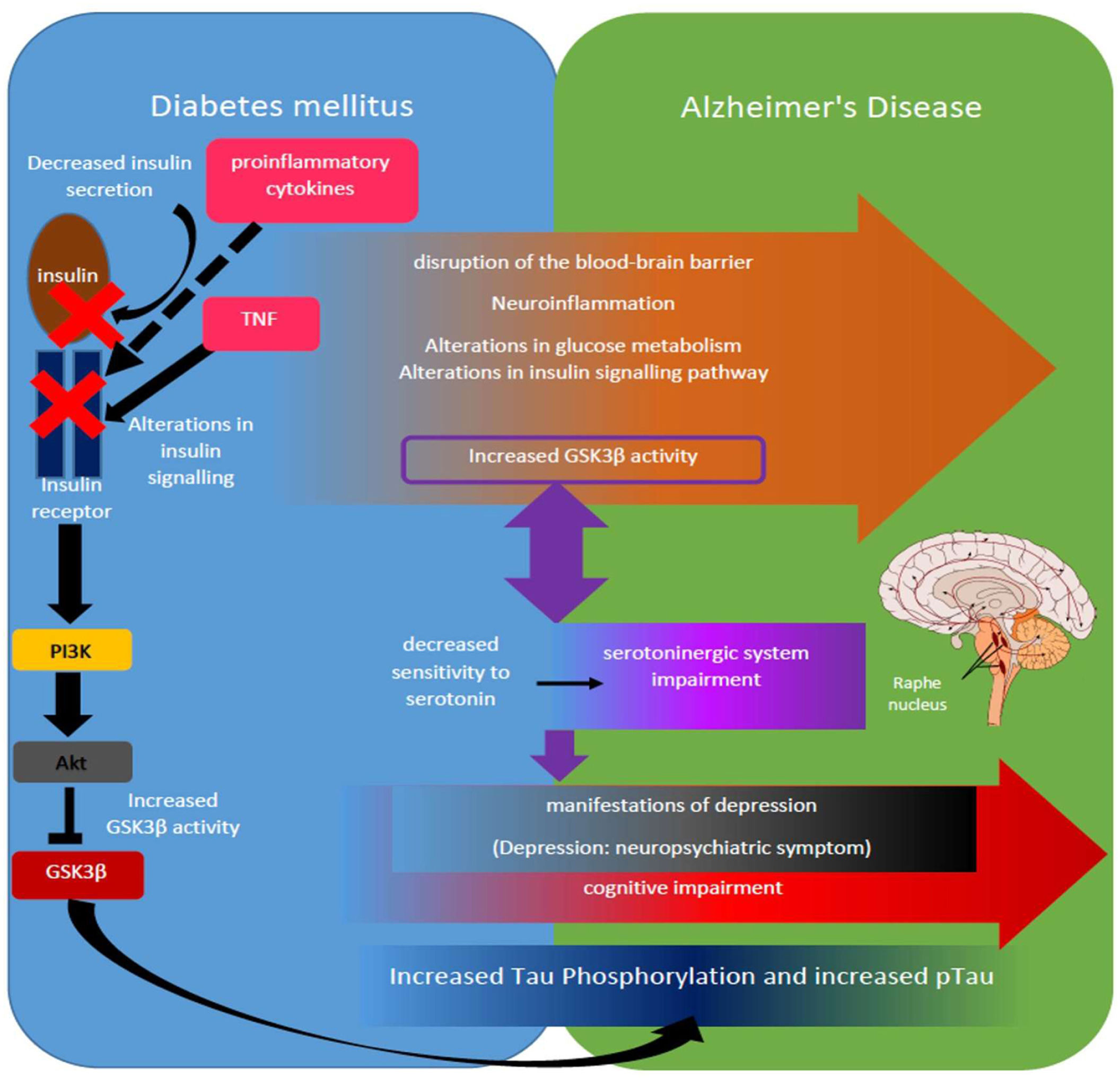

Molecularly it highlights the role of GSK3β whose increased activity in AD is linked to decreased serotonin sensitivity in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of DM subjects linked to depressive manifestations such as anhedonia and hypoactivity,93 whereas increased GSK3β activity in AD subjects has been associated with decreased serotonergic activity and significantly decreased cell proliferation in the hippocampus and depressive manifestations such as hypoactivity in animal models61 (figure 1).

Adaptation of the serotonergic hypothesis from the perspective of the DM-EA link. Some of the alterations present in DM that are under study as part of the DM-EA link are listed (orange arrow), highlighting for example those mechanisms such as increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and TNF, decreased insulin release and alterations in insulin receptor activation, which interfere with the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway, increasing the activity of said kinase (left side schematic in blue box), highlights at this point also the role of GSK3β as one of the important kinases in Tau phosphorylation and the generation of hyperphosphorylated Tau (pTau) (dark blue box). Increased GSK3β activity further suggests a bidirectional synergistic relationship with decreased serotonin sensitivity in DM subjects and subsequent impairment of the serotonergic system, mainly at the level of the raphe nuclei in AD subjects (purple boxes and arrow). In turn, alterations in serotonergic signaling have been linked to the development of depressive behaviors (black box), which in turn depend on the establishment of mild cognitive impairment in the case of DM and both mild and advanced in AD (red arrow).

Regarding the temporal relationship it should be noted that depression is among the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms present both in the prediabetes stage up to DM.74 Whereas in AD subjects the development of neuropsychiatric depressive symptoms occurs markedly in the early stages of this disease.42

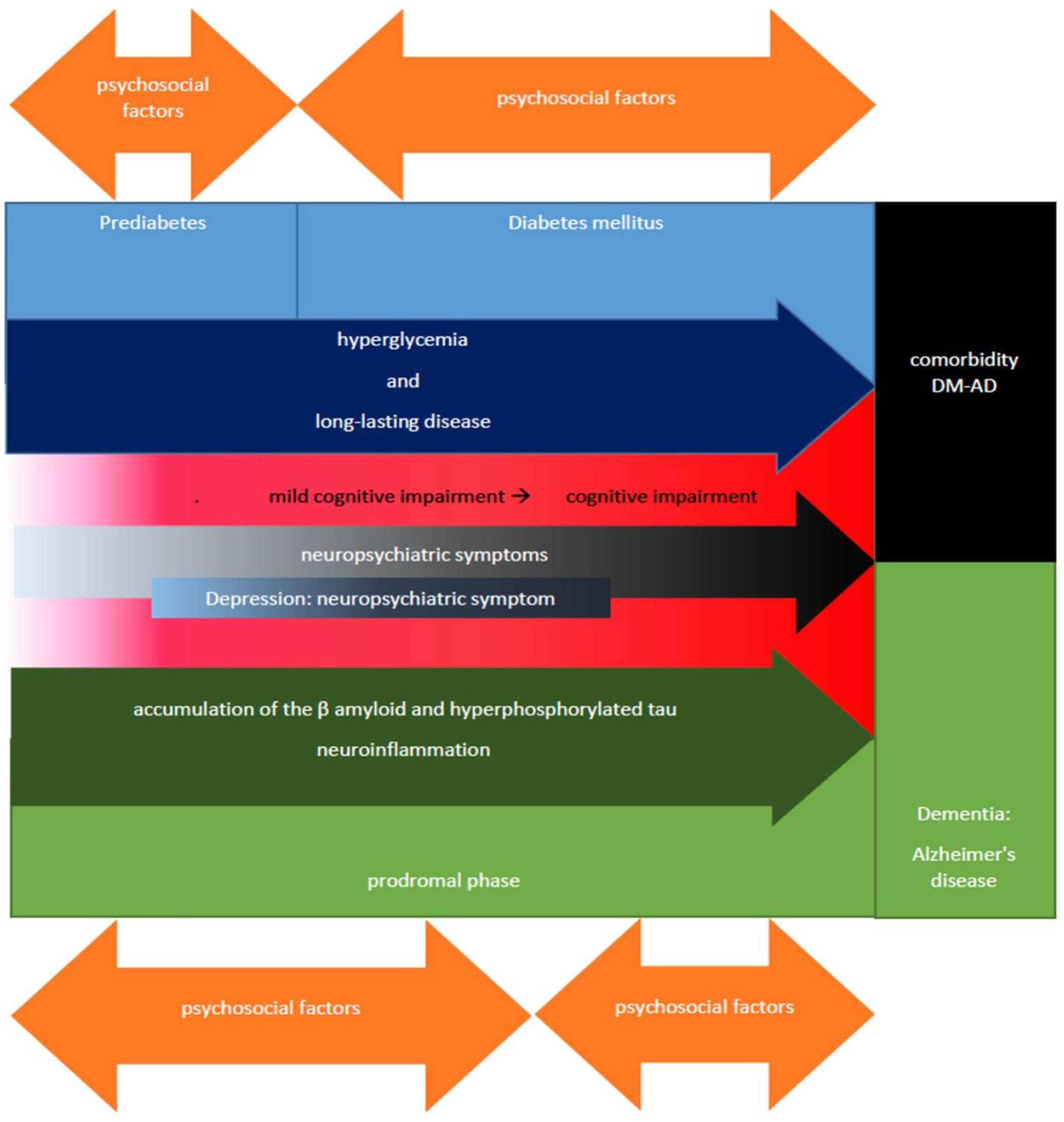

Which leads us to propose that the presence of neuropsychiatric depressive symptoms that develop during the phase of mild cognitive impairment in subjects with DM prematurely signal a pathway that will progressively lead towards the development of dementia, also considering as an important factor in this process the dysfunction of GSK3β and the serotonergic system of the patients, resulting in behavioral manifestations and referred symptoms of depressive type, to later start with the dementia phase during which other neuropsychiatric symptoms corresponding to phases of greater cognitive impairment may progressively develop as in the case of AD (figure 2).

Diagram of the temporal relationship between DM-cognitive impairment/depression-EA. In this scheme highlights the temporal relationship between prediabetes and DM, the former being a phase that precedes the development of DM (blue boxes), some of the common characteristics of these entities such as hyperglycemia and prolonged time of suffering from the disease (dark blue arrow) favor the development of mild cognitive impairment that can progress to cognitive impairment (red box) until reaching the stage of dementia being in some cases of AD type, leading to DM-AS comorbidity (black box). The stage of cognitive impairment and mainly mild cognitive impairment, are crucial and timely for the identification of neuropsychiatric manifestations of cognitive impairment (black arrow) such as depression (dark blue box) that characterize the prodromal phase that precedes the development of AD and the initial stages of AD (green boxes), whose progression depends, among other factors, on the increased production and deposition of β-amyloid and hyperphosphorylated Tau, as well as neuroinflammation (dark green arrow). Finally, the bidirectional orange arrows represent the influence of psychosocial factors both to improve and to aggravate each of the phases; some of these, such as prediabetes and the prodromal phase of mild cognitive impairment linked to it, are reversible depending on timely interventions as part of the patient's comprehensive treatment, highlighting axes such as glycemic control based on healthy lifestyles, psychological care and in certain cases pharmacological treatments, hence the timely detection of neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression during clinical practice provides a window of opportunity to address and prevent complications such as cognitive impairment and the subsequent development of dementia linked to the progression of entities such as prediabetes and diseases such as DM.

Based on the observation of the temporal relationship between DM, AD and cognitive impairment, we consider that the progression pathway in general terms consists of DM, DM with cognitive impairment, a phase during which depression develops as a neuropsychiatric symptom and finally AD. Since the period of cognitive impairment in patients with DM is a crucial stage in which various neuropsychiatric symptoms are present as prodromal indicators of dementia, the presence of depression is very frequent both in DM and in the early stages of AD.

It should be noted that the presence of depressive symptoms does not exclude the possibility of developing other types of neuropsychiatric symptoms both in the early stages of DM and AD and in the late stages, although for the purposes of this article we focus on the role of depressive symptoms, leaving open the possibility of investigating the role that other neuropsychiatric symptoms may play in the DM-AD and DM-dementia link, also highlighting the role of cognitive impairment as one of the determinants and regulators of the development of each of these symptoms.

Considering the evidence presented in this article, the relationship of depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom in both DM and AD suggests a close relationship with increased GSK3β activity and decreased serotonergic activity, which from the perspective of AD leads us to pay more attention to the study of the evidence for the monoamine deficiency hypothesis, mainly in alterations of serotonin signaling.

One of the methodological obstacles that we identified during this study has been the lack of differentiation between idiopathic depression and depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom, mainly in older studies, since in more recent studies the delimitation of both entities is more frequent, so that in the future the study of the influence of depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom could be better evaluated both in the DM-AD link and as part of other conditions.

The multidimensionality of these entities is seen as a challenge to know if depressive symptoms really point to a pathway of association between DM and AD, because, although the molecular mechanisms begin to point in this direction, the study of the psychosocial component is less conclusive mainly because it includes many variables that are difficult, but not impossible, to measure and consider when evaluating the study subjects. Faced with this challenge, the use of animal models and the analysis of their behaviors for the study of this link could provide evidence that reinforces the idea that depressive symptoms are a common point between DM and AD.

ConclusionsThe analysis of the evidence collected suggests that mild cognitive impairment and the development of depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom are a piece of the DM-AD link considering the temporal relationship between these entities (DM, cognitive impairment, depression, and AD) as well as the molecular mechanisms under study, highlighting among these the increase in GSK3β activity and decrease in serotonergic activity. From this perspective we have pertinent to deepen in the study of the evidence that addresses the hypothesis of monoamine deficiency, mainly concerning serotonin in both AD and DM.

At the same time we found that the correct delimitation of idiopathic depression and depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom are fundamental for the understanding of the evolution of diseases linked to the development of these entities such as in the case of DM and AD, since both the diagnostic tools used in clinical practice and the histopathological and molecular analysis suggest important differences between idiopathic depression and depression as a neuropsychiatric symptom, which will also allow us to perform a better approach and treatment depending on each entity.

FundingKAHC received a doctoral scholarship number 958097 from CONACYT, Mexico.

Conflicts of interestsNone.