Social support promotes feelings of stability, predictability and self-esteem and reduces the social isolation, because information, tangible assistance and emotional support can be obtained from the social network.

MethodsWe conducted a narrative review of the international empirical literature to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of social support and social networks on patients diagnosed with myasthenia gravis. The following databases were consulted: CINAHL, MEDLINE, APA PsycInfo, SCOPUS and Web of Science. Information was collected up to 2nd December 2022.

ResultsThe initial search generated 46 articles, but after the exclusion criteria had been applied, the total number of articles analysed was 13.

ConclusionsThe symptoms of myasthenia gravis, especially ptosis and slurred speech, can have a major psychosocial impact and a negative effect on interaction social.

El soporte social promueve sentimientos de estabilidad, previsibilidad y autoestima y reduce el aislamiento social, ya que de la red social se puede obtener información, ayuda tangible y apoyo emocional.

MetodologíaSe realizó una revisión narrativa de la literatura empírica internacional para proporcionar una comprensión global del impacto del soporte social y las redes sociales en pacientes diagnosticados de miastenia gravis. Se consultaron las siguientes bases de datos: CINAHL, Medline, APA PsycInfo, Scopus y Web of Science. La información se recopiló hasta el 2 de diciembre de 2022.

ResultadosLa búsqueda inicial generó 46 artículos, pero una vez aplicados los criterios de exclusión, el número total de artículos analizados fue de 13.

ConclusionesLos síntomas de la miastenia gravis, especialmente la ptosis y la dificultad para hablar, pueden tener un gran impacto psicosocial y un efecto negativo en la interacción social.

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease characterised by fatigability and muscle weakness at the proximal level, mediated by antibodies against acetylcholine receptors and/or other post-synaptic membrane proteins. It is characterised by fluctuating muscle weakness of proximal predominance, which leads to symptoms such as ptosis, bulbar weakness (dysarthria, dysphagia or dysphonia), and respiratory dysfunction.1

A chronic and fluctuating pathology, it can have a negative impact on health-related quality of life, especially in the family and social domains.2 Social support can therefore protect chronic patients from stress by helping them to perceive the experience as less harmful or threatening, and providing them with valuable coping resources.3

There are several definitions of functional social support. House's (1981) definition cited in Ref. 4 refers to social support as “an interpersonal transaction that includes one of four categories: (a) emotional support (displays of empathy, love and trust), (b) instrumental support (behaviours aimed at directly solving the recipient's problems), (c) informational support (receiving useful coping information) and (d) evaluative support (information relevant to self-evaluation or social comparisons, excluding the affective aspect that might accompany this information)”. Positive social support has been linked to physical health, mental health and longevity.5 Thus, social support promotes feelings of stability, predictability and self-esteem, and reduces the social isolation that promotes detrimental health effects, because information, tangible assistance and emotional support can be obtained from the social network.3,6 Social support can also protect chronic patients from stress by helping them to perceive the experience as less harmful or threatening, and providing them with valuable coping resources.3

It should be noted that social support can be classified into received and perceived support. Received social support refers to the receipt of supportive actions, while perceived support is the person's subjective belief of the assistance of others in a situation or life circumstance. This distinction is important, as some people may receive support but not perceive it, and therefore it cannot be used to generate health benefits.7

A concept related to functional social support is the social network. The social network refers to the relational structure that integrates the people themselves into their social environment through which support can be provided. The most important structural dimensions of the social network are: size (the number of people forming the social network or personal contacts), density (the interconnections between its members), reciprocity (the degree of equal exchange of resources between the different parties), kinship (whether the social network consists only of relatives or not) and homogeneity (the similarities or differences between the members of a network in terms of a given variable).7 People's social support and networks seem to influence the perception or management of their disease, but it is not known how they influence patients diagnosed with myasthenia gravis.

For all these reasons, this study compiled and summarised the international literature on the impact of social support and social networks on patients diagnosed with myasthenia gravis so as to provide greater insight into this issue.

MethodsA narrative review was carried out and the results were presented in accordance with PRISMA guidelines.8 The articles were selected by analysing the databases CINAHL, MEDLINE, APA PsycInfo, SCOPUS and Web of Science and carrying out a manual search. All the information was compiled up to 2nd December 2022. The search strategy was (“social support” OR “social network” OR “social activity” OR “social satisfaction” OR “social participation”) AND “myasthenia gravis”. Inclusion criteria were: (1) they had to be written in Spanish or English; (2) they had to deal with individuals diagnosed with myasthenia gravis; (3) they had to discuss social support and social network in patients with myasthenia gravis. In contrast, the exclusion criteria were: (1) they involved patients with psychiatric disorders; (2) the publications are over thirteen years old.

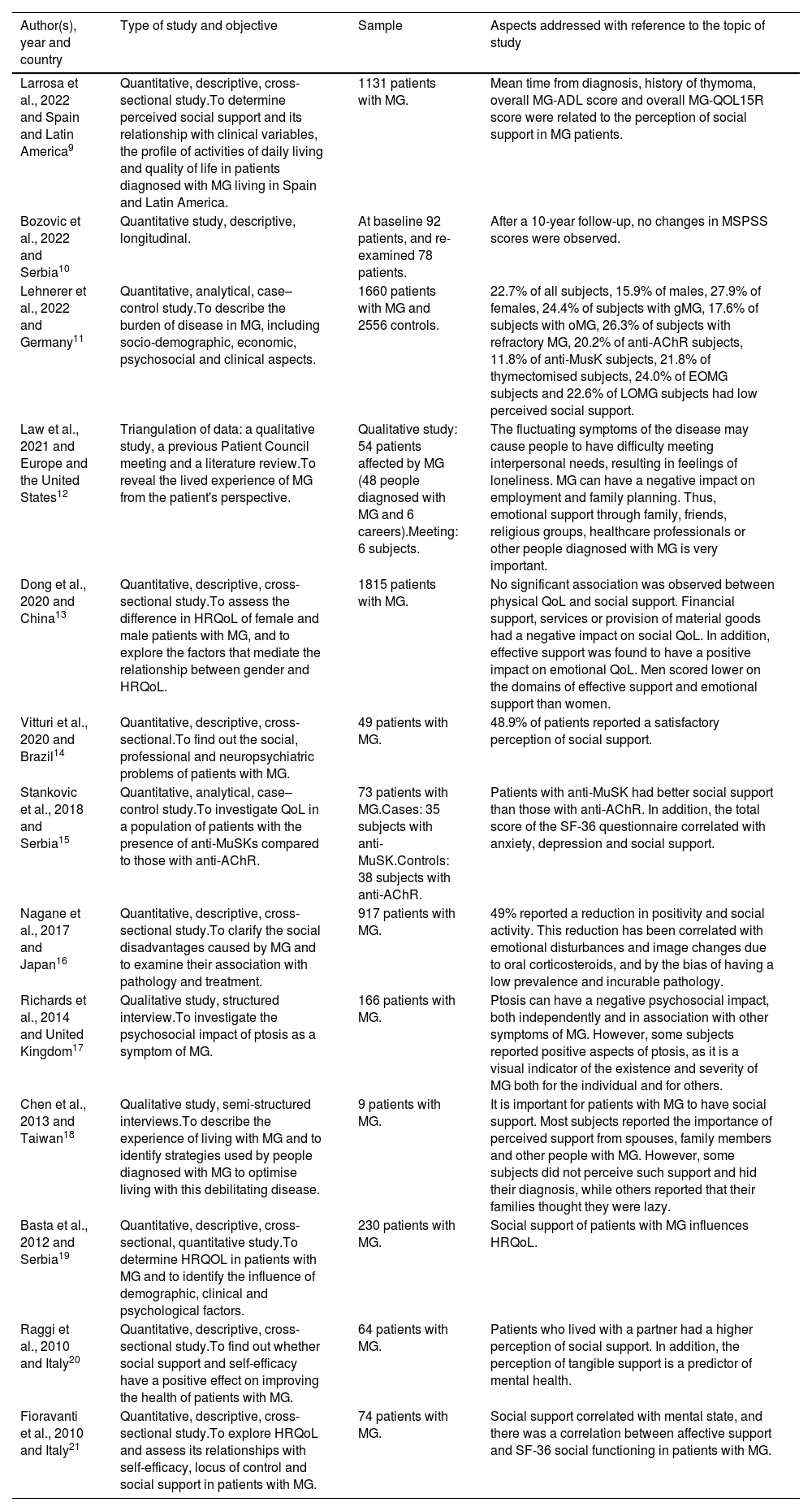

Results and discussionThe initial search generated 46 articles, article titles and abstracts were examined and assessed for eligibility using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. During the selection process, the authors addressed any discrepancies that arose through consensus. Finally, 13 articles were selected for review (Table 1). The data extracted from the articles analysed were organised in a table (Table 2).

Characteristics of studies.

| Author(s), year and country | Type of study and objective | Sample | Aspects addressed with reference to the topic of study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larrosa et al., 2022 and Spain and Latin America9 | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study.To determine perceived social support and its relationship with clinical variables, the profile of activities of daily living and quality of life in patients diagnosed with MG living in Spain and Latin America. | 1131 patients with MG. | Mean time from diagnosis, history of thymoma, overall MG-ADL score and overall MG-QOL15R score were related to the perception of social support in MG patients. |

| Bozovic et al., 2022 and Serbia10 | Quantitative study, descriptive, longitudinal. | At baseline 92 patients, and re-examined 78 patients. | After a 10-year follow-up, no changes in MSPSS scores were observed. |

| Lehnerer et al., 2022 and Germany11 | Quantitative, analytical, case–control study.To describe the burden of disease in MG, including socio-demographic, economic, psychosocial and clinical aspects. | 1660 patients with MG and 2556 controls. | 22.7% of all subjects, 15.9% of males, 27.9% of females, 24.4% of subjects with gMG, 17.6% of subjects with oMG, 26.3% of subjects with refractory MG, 20.2% of anti-AChR subjects, 11.8% of anti-MusK subjects, 21.8% of thymectomised subjects, 24.0% of EOMG subjects and 22.6% of LOMG subjects had low perceived social support. |

| Law et al., 2021 and Europe and the United States12 | Triangulation of data: a qualitative study, a previous Patient Council meeting and a literature review.To reveal the lived experience of MG from the patient's perspective. | Qualitative study: 54 patients affected by MG (48 people diagnosed with MG and 6 careers).Meeting: 6 subjects. | The fluctuating symptoms of the disease may cause people to have difficulty meeting interpersonal needs, resulting in feelings of loneliness. MG can have a negative impact on employment and family planning. Thus, emotional support through family, friends, religious groups, healthcare professionals or other people diagnosed with MG is very important. |

| Dong et al., 2020 and China13 | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study.To assess the difference in HRQoL of female and male patients with MG, and to explore the factors that mediate the relationship between gender and HRQoL. | 1815 patients with MG. | No significant association was observed between physical QoL and social support. Financial support, services or provision of material goods had a negative impact on social QoL. In addition, effective support was found to have a positive impact on emotional QoL. Men scored lower on the domains of effective support and emotional support than women. |

| Vitturi et al., 2020 and Brazil14 | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional.To find out the social, professional and neuropsychiatric problems of patients with MG. | 49 patients with MG. | 48.9% of patients reported a satisfactory perception of social support. |

| Stankovic et al., 2018 and Serbia15 | Quantitative, analytical, case–control study.To investigate QoL in a population of patients with the presence of anti-MuSKs compared to those with anti-AChR. | 73 patients with MG.Cases: 35 subjects with anti-MuSK.Controls: 38 subjects with anti-AChR. | Patients with anti-MuSK had better social support than those with anti-AChR. In addition, the total score of the SF-36 questionnaire correlated with anxiety, depression and social support. |

| Nagane et al., 2017 and Japan16 | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study.To clarify the social disadvantages caused by MG and to examine their association with pathology and treatment. | 917 patients with MG. | 49% reported a reduction in positivity and social activity. This reduction has been correlated with emotional disturbances and image changes due to oral corticosteroids, and by the bias of having a low prevalence and incurable pathology. |

| Richards et al., 2014 and United Kingdom17 | Qualitative study, structured interview.To investigate the psychosocial impact of ptosis as a symptom of MG. | 166 patients with MG. | Ptosis can have a negative psychosocial impact, both independently and in association with other symptoms of MG. However, some subjects reported positive aspects of ptosis, as it is a visual indicator of the existence and severity of MG both for the individual and for others. |

| Chen et al., 2013 and Taiwan18 | Qualitative study, semi-structured interviews.To describe the experience of living with MG and to identify strategies used by people diagnosed with MG to optimise living with this debilitating disease. | 9 patients with MG. | It is important for patients with MG to have social support. Most subjects reported the importance of perceived support from spouses, family members and other people with MG. However, some subjects did not perceive such support and hid their diagnosis, while others reported that their families thought they were lazy. |

| Basta et al., 2012 and Serbia19 | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional, quantitative study.To determine HRQOL in patients with MG and to identify the influence of demographic, clinical and psychological factors. | 230 patients with MG. | Social support of patients with MG influences HRQoL. |

| Raggi et al., 2010 and Italy20 | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study.To find out whether social support and self-efficacy have a positive effect on improving the health of patients with MG. | 64 patients with MG. | Patients who lived with a partner had a higher perception of social support. In addition, the perception of tangible support is a predictor of mental health. |

| Fioravanti et al., 2010 and Italy21 | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study.To explore HRQoL and assess its relationships with self-efficacy, locus of control and social support in patients with MG. | 74 patients with MG. | Social support correlated with mental state, and there was a correlation between affective support and SF-36 social functioning in patients with MG. |

MG: myasthenia gravis; MG-ADL: myasthenia gravis activities of daily living; MG-QOL15R: Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15-item Scale – Revised; anti-AChR: antibodies against serum acetylcholine receptor; anti-MusK: antibodies against muscle-specific tyrosine kinase receptor; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey; QoL: quality of life; HRQoL: health-related quality of life; gMG: generalised myasthenia gravis; oMG: ocular myasthenia gravis; EOMG: early onset myasthenia gravis (≤45 years old); LOMG: late onset myasthenia gravis (>45 years old); MSPSS: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.

Social support is important for patients with myasthenia gravis.18 Patients with antibodies against muscle-specific tyrosine kinase receptor (anti-MusK) perceived greater social support than patients with antibodies against serum acetylcholine receptor (anti-AChR).14,15 Also, a history of thymoma and a delay in the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis of more than two years are associated with an increased risk of low perceived social support.9 Higher social support has also been found to be associated with higher health-related quality of life and improved mental state.9,13,15,19,21

Myasthenia gravis had reduced positivity and social activity in 49% of subjects. This has been correlated with depressive state, mood and image changes due to oral corticosteroids, and bias due to the low prevalence and chronic disease.16 Patients with myasthenia gravis may have reduced facial function as a result of weakness, and their lack of expression may have a psychosocial impact, as seen in studies on facial paralysis.22 It has also been observed that the influence of myasthenia gravis symptoms can have a negative impact on the social functioning of the sufferer.17,23 Symptom severity has been found to be associated with perceived social support in patients with myasthenia gravis.9 Female sex, bulbar symptoms, severity in current state and treatment with oral corticosteroids ≥20 myasthenia gravis/day have been associated with decreases in both activity and social positivity.16 Therefore, patients with myasthenia gravis may require understanding, acceptance and social support if they are to cope with life circumstances and increase their health-related quality of life.16,19

Using House's (1981) concept of social support, we established the following categories: emotional support, instrumental support, informational support and evaluative support.

Emotional supportEmotional support is of the utmost importance for people diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, whether it comes from family relationships or friendships, religious groups, healthcare professionals or other people with the same diagnosis.12 With affective support, individuals receive expressions of love and affection from their closest social network. In patients with myasthenia gravis, emotional support had a positive impact on health-related quality of life at the emotional level. Males scored lower in the domain of emotional and affective support than females.13

Most subjects reported the importance of perceived support from spouses, family members and other people with myasthenia gravis.18 However, some did not perceive this support and hid their diagnosis, and others reported a lack of understanding.12,18

If participants experienced discrimination at any time, they tended to hide the diagnosis so that they would not miss any opportunities to socialise.18 It should be noted that the fluctuating symptoms of the disease may cause them to have to cancel plans at the last minute, rely on others, or miss events with family and friends. As a result, people with myasthenia gravis may experience feelings of guilt because they are letting their family and friends down by cancelling plans, or they may think that they have done something to worsen the illness.12

Myasthenia gravis has been observed to have a negative impact on relationships, which can lead to feelings of loneliness.12 The symptoms of the disease are challenging for both the individuals and their families, but patients living with a partner tend to report higher levels of social support.18,20 However, women report less perceived social support than men.11 In Ref. 23 it is reported that myasthenia gravis has led to strained marital relationships in several women under the age of 44 and, in two cases, even caused the marriage to break down. In Ref. 11, however, approximately 33% of all the participants separated or divorced as a result of myasthenia gravis, and 16.8% had their family planning affected. In contrast, 4 of the 11 married women over 44 years of age reported that myasthenia had made them even more attached to their husbands.23

Many participants accessed support groups of other patients to share their experiences.18 In a study on patients with myasthenia gravis, it was observed that 55.5% were members of patient associations, and 71.6% had acquaintances with the same diagnosis.24 This support received from other people with the same diagnosis has been reported to help them understand that “they are not alone” and to show them how others in the same situation cope with the disease.12 Support groups often allow patients to attend sessions with members of their social network and this improves communication within existing relationships by increasing understanding of myasthenia gravis.12

People with myasthenia gravis may feel a sense of disconnection from their doctors, largely due to barriers to communication such as lack of time or differences in perception in the management of their condition.12 This can mean that when they begin to experience symptoms of a crisis, people with myasthenia gravis find it difficult to know when and how to seek medical help, as it is not well defined.12 Some people do not like to bother health professionals and the distance to the hospital is a barrier to early referral.12

Instrumental supportAs far as employment is concerned, it improves their self-esteem, expands their social network and generates feelings of personal satisfaction and usefulness.14,16 In addition, while they carry out their tasks, they are stimulated both mentally and physically.14

Employment can be challenging for people with myasthenia gravis due to the symptoms of the disease, and they may find it difficult to work full-time. It has been observed that 25.9% were employed full-time and 14.9% part-time.9 Sometimes patients with myasthenia gravis have to hide their illness in order to keep their job.18 A total of 72.6% of the subjects reported having limited employment opportunities due to their myasthenia gravis.11 In detail, 45.8% were unable to work, 18.6% reported recurrent inability to work, 12.7% had to reduce their working hours, 7.8% were unable to return to their same profession (occupational disability) and 2.2% were unemployed.11

At the economic level, 35.9–46.9% of subjects started earning less after a diagnosis of myasthenia gravis.14,16 It has also been suggested that long-term hospital stays (˃1 month) and the need for years of hospital care correlated with a decrease in income.16

The impact of the disease on driving can be a barrier to employment and affect a person's independence.12 It is also worth mentioning that employers’ attitudes may vary from workplace to workplace or country to country, and this can affect treatment adherence. For example, a person with myasthenia gravis may not feel able to take time off work to receive treatment with intravenous human immunoglobulins.12

Information supportIt has been documented that a large proportion of patients stated that they were afraid to go to hospital not because of myasthenia gravis itself but because the doctors did not know as much as they did about their disease.23

However, it has been observed that some patients, after seeking information about myasthenia gravis, were emotionally confused by the information leaflets provided by their own doctors,18 which from the patients’ perspective are often poor because of how they deal with adverse effects and treatment progress.12 Thus, there is a need for greater understanding and consideration of how treatment affects the lives of people with myasthenia gravis.

Likewise, people with myasthenia gravis need more information, education and support about family planning. Advice from healthcare providers about myasthenia gravis and pregnancy, and better guidance on treatment in this period can have a major influence on the decision of women with myasthenia gravis to have children or not. And this has an effect on their relationships.12

Evaluative supportSeveral participants said that ptosis made them anxious in social situations and some tended to avoid social contact in anticipation of negative reactions.17 The symptoms of myasthenia gravis hindered verbal and non-verbal communication12,17 and strangers who were unaware of their condition often thought they were faking, drunk or had taken drugs.17,23

Some participants were stigmatised by others as ‘rude or dismissive’ for their ptosis or lack of eye contact, and many subjects have reported that their ptosis has increased their self-consciousness, emotional distress, depression, and social anxiety.17 Several authors have reported that subjects with myasthenia gravis were socially isolated because they were embarrassed about their appearance and speechlessness, both the result of their ptosis.17,18

Patients with ptosis tended to adopt attitudes of concealment by wearing dark glasses, changing their hairstyle or varying their mannerisms.17 One study observed that a large proportion of subjects felt embarrassed when interacting with strangers if they had difficulty smiling because of facial muscle fatigue.23

Some subjects reported that ptosis was a visible indicator of their general condition and allowed them to monitor and control their own symptoms.17 It also made their condition visible to friends and family, as other symptoms are not so readily noticed.17 This need to have their condition externally validated was described by many patients who had experienced a delay in the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis.17

ConclusionsSocial support is important for individuals with myasthenia gravis, as it gives them information, tangible assistance and emotional support, helps them to cope with life circumstances and improves their health-related quality of life. However, the symptoms of myasthenia gravis, especially ptosis and slurred speech, can have a major psychosocial impact and a negative effect on interaction social.

This review has some limitations as most of the studies are cross-sectional and analyse perceived social support and not the social support received by patients with myasthenia gravis. However, to approach myasthenia gravis from the perspective of the biopsychosocial model, it is necessary to understand the psychological, biological and social factors that influence the functioning and perception of people. All these elements are required if care is to be individualised, self-care interventions designed and adherence to treatment improved. Therefore, given the current inconclusive evidence and limited literature, further study of social support in patients with myasthenia gravis is needed. Future research should investigate the effect of cultural differences on the perception of social support in patients with myasthenia gravis.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.