Tuberculosis in solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients is a clinical challenge. This opportunistic infection has atypical presentations and raises concerns due to both the toxicity of antifimic drugs and their interaction with immunosuppressive therapy that may result in graft loss or death. This retrospective review of cases of active tuberculosis after SOT describes the management of this infection in a hospital in Argentina. Between January 2006 and June 2022, 27 transplanted patients had positive cultures for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Their median age was 56 years; 78% were male. Ten (37%) patients had extra-pulmonary or disseminated tuberculosis. Twenty-five (93%) patients required invasive procedures to reach a diagnosis. In 17 (63%) patients, the initial diagnosis was based on a positive Ziehl-Neelsen smear. Twenty-four patients received a four-drug induction treatment without rifampin. Clinical cure was 80% and crude mortality was 20%.

La tuberculosis en pacientes con trasplante de órgano sólido (TOS) constituye un desafío clínico. Es una infección oportunista que presenta formas clínicas atípicas y dificultades inherentes al tratamiento. Esta revisión retrospectiva de casos de tuberculosis activa post-TOS describe el manejo de esta infección en un hospital de Argentina. Entre enero de 2006 y junio de 2022, 27 pacientes trasplantados tuvieron cultivos positivos para Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. La mediana de edad fue 56 años; el 78% correspondió al sexo masculino. Diez (37%) pacientes tuvieron tuberculosis extrapulmonar o diseminada. Veinticinco (93%) pacientes requirieron procedimientos invasivos para llegar al diagnóstico. Un resultado positivo en la coloración de Ziehl-Neelsen fue la prueba diagnóstica inicial en 17 (63%) pacientes. Veinticuatro pacientes recibieron tratamiento de inducción con cuatro drogas sin rifampicina. La cura clínica fue del 80% y la mortalidad cruda, del 20%.

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by one of the members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, most commonly M. tuberculosis. Prior to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, it was the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent6.

M. tuberculosis is ubiquitous and spread via airborne transmission. Exposed human hosts may clear the bacterium, or may develop a primary disease or a latent infection with the possibility of clinical reactivation many years later. The rate of reactivation increases substantially in immunosuppressed patients14.

Tuberculosis in solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients is one of the most important opportunistic infections. This group of patients has an additional risk of developing active tuberculosis (TB) based on their immunosuppression status with a reported incidence of TB 20 to 74 times higher than in the general population3. In addition, diagnosis may be quite difficult due to nonspecific symptoms and atypical or extra-pulmonary presentations. Moreover, drug-related toxicity and interactions between immunosuppressive and antitubercular drugs are associated with appreciable morbidity and mortality3,14.

In Argentina, the national incidence of TB in the general population during 2024 was 35.40 cases per 100000 inhabitants with a mortality rate estimated in 1.61 per 100000 inhabitants4. However, there is scarce information about this opportunistic infection in SOT recipients. A single-center study conducted between 1986 and 1995 reported a cumulative incidence of 3.64% of tuberculosis among kidney graft recipients8. More recently, another single-hospital study reported a cumulative incidence of 2.17% and 1.92% of TB in kidney and kidney-pancreatic transplant recipients, respectively12. Current data on tuberculosis in different graft-type SOT recipients is required to improve clinical guidelines and decisions based on local experience.

The aim of this study is to describe the epidemiology, clinical characteristics, treatment and outcome of TB among SOT recipients admitted to a tertiary hospital from Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

All confirmed cases of TB after SOT, diagnosed between January 2006 and June 2022, were retrospectively reviewed to assess the available data. A diagnosis was considered confirmed only when M. tuberculosis was isolated from culture. TB was defined as pulmonary (only lung parenchymal involvement), extra-pulmonary (involvement of organs other than the lungs), or disseminated (involvement of at least two different noncontiguous organs)2. A positive response to the tuberculin skin test (TST) during the pre-transplant evaluation was defined as an induration ≥5mm in diameter 48–72h after the administration of 2IU of tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) for patients in the waiting list, and ≥10mm for living donors13. A second TST as booster was not performed and the interferon-γ-release assay (IGRA) was not available. An updated pre-transplant evaluation was reported every 1 or 2 years according to the institutional protocol. Clinical samples sent to the laboratory for isolating M. tuberculosis were processed and cultured in accordance with standard methods. Molecular tests for diagnosis of tuberculosis were not routinely available during the period of study. Patients were diagnosed and treated according to institutional clinical guidelines and criteria of the treating clinicians. This study had the ethical approval of the Teaching and Research Department of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Favaloro (order number 23/7-9-2024).

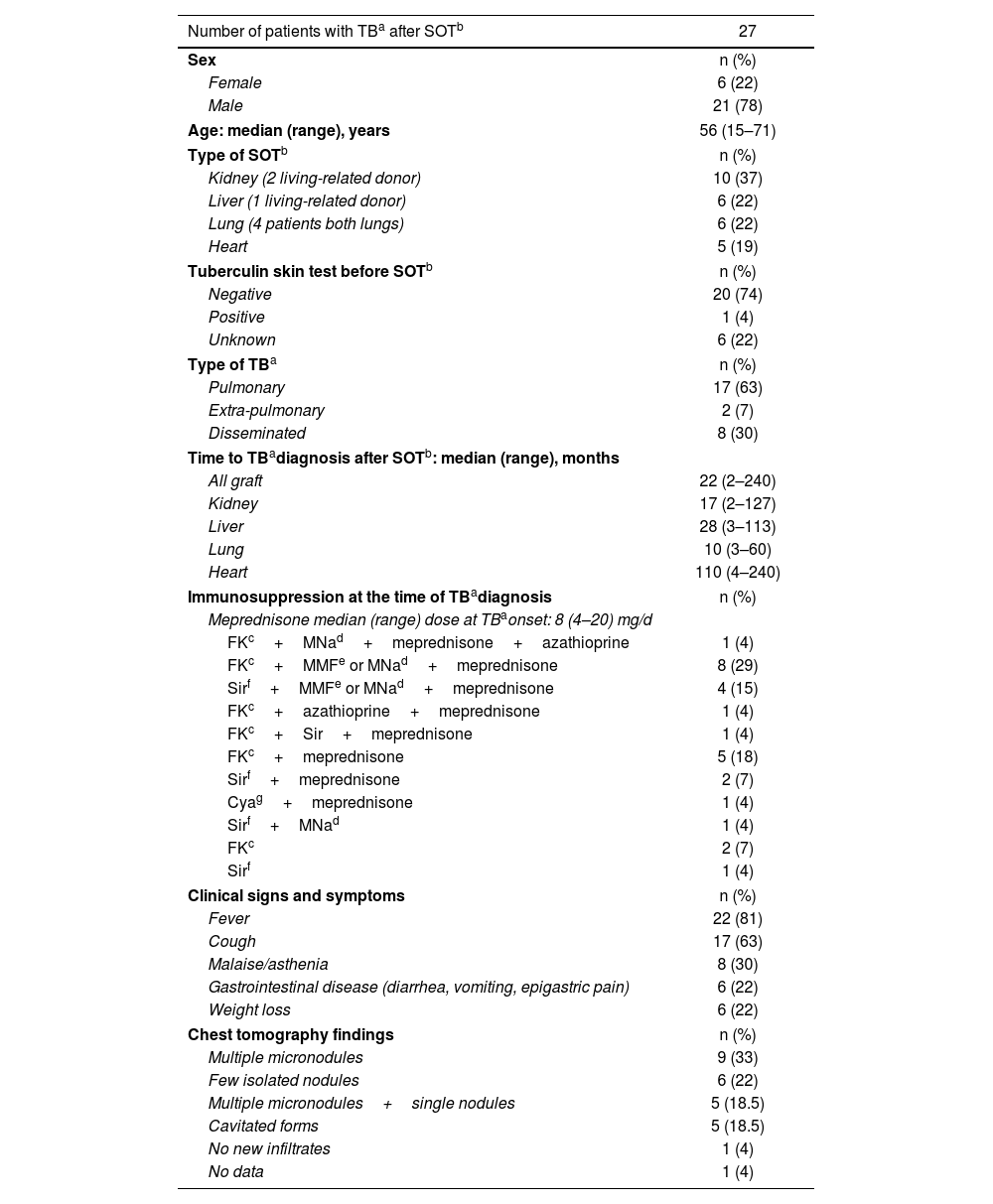

From the beginning of 2006 to mid-2022, our hospital, a specialized center in cardiology and solid organ transplantation, performed 2491 solid organ transplants. During the same period, 27 patients (10 kidney, 6 liver, 6 lung, and 5 heart recipients) were diagnosed with TB after SOT. Patients are listed in Supplementary Table S1. All but one were primary transplant recipients. Median (range) age was 56 (15–71) years and most of them (78%) were male (Table 1). One patient had human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (viral load <20copies/ml at the time of TB diagnosis) and two patients had chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Epidemiology of active tuberculosis after solid organ transplantation.

| Number of patients with TBa after SOTb | 27 |

|---|---|

| Sex | n (%) |

| Female | 6 (22) |

| Male | 21 (78) |

| Age: median (range), years | 56 (15–71) |

| Type of SOTb | n (%) |

| Kidney (2 living-related donor) | 10 (37) |

| Liver (1 living-related donor) | 6 (22) |

| Lung (4 patients both lungs) | 6 (22) |

| Heart | 5 (19) |

| Tuberculin skin test before SOTb | n (%) |

| Negative | 20 (74) |

| Positive | 1 (4) |

| Unknown | 6 (22) |

| Type of TBa | n (%) |

| Pulmonary | 17 (63) |

| Extra-pulmonary | 2 (7) |

| Disseminated | 8 (30) |

| Time to TBadiagnosis after SOTb: median (range), months | |

| All graft | 22 (2–240) |

| Kidney | 17 (2–127) |

| Liver | 28 (3–113) |

| Lung | 10 (3–60) |

| Heart | 110 (4–240) |

| Immunosuppression at the time of TBadiagnosis | n (%) |

| Meprednisone median (range) dose at TBaonset: 8 (4–20) mg/d | |

| FKc+MNad+meprednisone+azathioprine | 1 (4) |

| FKc+MMFe or MNad+meprednisone | 8 (29) |

| Sirf+MMFe or MNad+meprednisone | 4 (15) |

| FKc+azathioprine+meprednisone | 1 (4) |

| FKc+Sir+meprednisone | 1 (4) |

| FKc+meprednisone | 5 (18) |

| Sirf+meprednisone | 2 (7) |

| Cyag+meprednisone | 1 (4) |

| Sirf+MNad | 1 (4) |

| FKc | 2 (7) |

| Sirf | 1 (4) |

| Clinical signs and symptoms | n (%) |

| Fever | 22 (81) |

| Cough | 17 (63) |

| Malaise/asthenia | 8 (30) |

| Gastrointestinal disease (diarrhea, vomiting, epigastric pain) | 6 (22) |

| Weight loss | 6 (22) |

| Chest tomography findings | n (%) |

| Multiple micronodules | 9 (33) |

| Few isolated nodules | 6 (22) |

| Multiple micronodules+single nodules | 5 (18.5) |

| Cavitated forms | 5 (18.5) |

| No new infiltrates | 1 (4) |

| No data | 1 (4) |

Data are presented as number of patients (percentage), n (%), except where ranges are noted.

Pre-transplant TST results were negative in 20 patients, not available in 6, and positive in only one of them (Table 1). The latter patient was a kidney recipient, yet there was no documented data regarding his epidemiology or prophylaxis; he developed TB three months after SOT. Other three patients reported close contact with a tuberculosis source after transplantation, suggesting de novo infections; only one of them had a documented pre-transplant negative result for the TST (Supplementary Table S1). There is no registered data to endorse a donor-derived transmission in any case. TST is still one of the recommended tests for the screening of latent tuberculosis in SOT candidates and in living donors13. However, the usefulness of this test is limited due to the anergy often observed in patients with end-stage organ disease14. Latent tuberculosis treatment is an effective TB prevention strategy; however, its risks, benefits, and timing require individualized assessment for every patient13.

Median (range) time to develop TB after SOT was 22 (2–240) months; median time to TB onset in lung recipients was the shortest (Table 1). Eleven out of 27 (41%) patients developed TB during the first year after SOT. Notably, 8 of them had recently received high doses of corticosteroids: 5 patients were receiving methylprednisolone ≥20mg/d at TB diagnosis and four patients had received methylprednisolone sodium succinate pulses at one (1 patient), two (1 patient) or 6 (2 patients) months prior for acute graft rejection. Drug-related immunosuppression, mainly due to high corticosteroid doses, is a major risk factor for TB. Although a high level of immunosuppression is more common during the first year after transplant, different clinical situations may lead to longer maintenance or additional reinforcement3,12,14. In this review, 15 (56%) patients were on a triple maintenance immunosuppressive scheme at the time of TB onset, even though half of them had been transplanted 1.8–10 years prior (Supplementary Table S1).

Fever and cough were the most common clinical signs (Table 1). Median (range) time elapsed between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis was 9 (1–62) days. Although 25 out of 27 (93%) patients showed new lung infiltrates, only 5 of them presented a cavity shape suggestive of tuberculosis. Nine (33%) patients exhibited multiple micronodules indistinguishable from other infections or inflammatory processes. In addition, the immunosuppressive status of SOT recipients predisposes them to developing various opportunistic infections that may mimic TB14. In this case series report, three patients showed fungal co-infections (1 Purpureocillium lilacinum and 1 Aspergillus fumigatus lung infections and 1 disseminated cryptococcosis with meningeal involvement), four patients exhibited cytomegalovirus reactivation and another presented influenza A co-infection (Supplementary Table S1).

Pulmonary TB was diagnosed in 63% of cases whereas disseminated and extra-pulmonary forms represented 37% of cases (Table 1). Disseminated TB was diagnosed in 8 patients (4 kidney, 2 liver and 2 heart recipients, respectively) compromising various tissues including deep organs (abdominal abscesses, 4 patients), lymph nodes (1 patient), joint fluid, articular tendons (1 patient), and muscle (3 patients). Extra-pulmonary TB was diagnosed in two patients (both liver recipients); one of them developed a laryngeal infection and the other had soft tissue involvement (Supplementary Table S1). The pulmonary form is the most frequent type of TB in SOT recipients as well as in immunocompetent patients. However, disseminated and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis are more relevant in the former group9,14. In an 11-year observational study from California, USA, the authors found a significant higher risk of extra-pulmonary and disseminated TB in SOT recipients than in the general population7. An international multicenter study, including few centers from Argentina, reported 42% of extra-pulmonary TB and 16% of disseminated infection in SOT patients16. More recently, Radisic et al. reported 56.7% of extra-pulmonary and disseminated forms in their single-hospital review in kidney and kidney-pancreatic recipients12. In contrast, the national tuberculosis surveillance reported 85.2% of pulmonary TB and only 11.9% of extra-pulmonary TB in the general population in 2024; in 2.9% of the reported cases, TB forms were not specified4. Our findings were in line with the expected epidemiology for SOT patients.

A positive Ziehl-Neelsen stain was the initial diagnostic test in 17 out of 27 (63%) patients; in the remaining cases, the diagnosis was made by culture growth. Nevertheless, 25 (93%) patients required invasive procedures to reach a diagnosis. The specimens were obtained via bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial biopsy at first, and then by lung biopsy and/or extra-pulmonary biopsies when necessary. In two patients, the diagnostic sample was sputum, although the bacilloscopy was positive in only one of them. The results of smears and cultures from patient samples are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. It is important to note that sputum smear results may be negative despite the presence of active lung disease. In addition, immunocompromised hosts are usually paucisymptomatic, and frequently present co-infections with other opportunistic agents. These facts underscore the need for invasive and sequential procedures to reach the diagnosis5.

Susceptibility to isoniazid and rifampin was evaluated in 19 out of 27 isolates and none of them exhibited resistance to these drugs. The remaining 8 isolates were considered susceptible to first-line drugs based on patient epidemiology. In Argentina, cases of multidrug resistance in M. tuberculosis were historically associated with outbreaks and are infrequent4. These strains have never been isolated in our hospital.

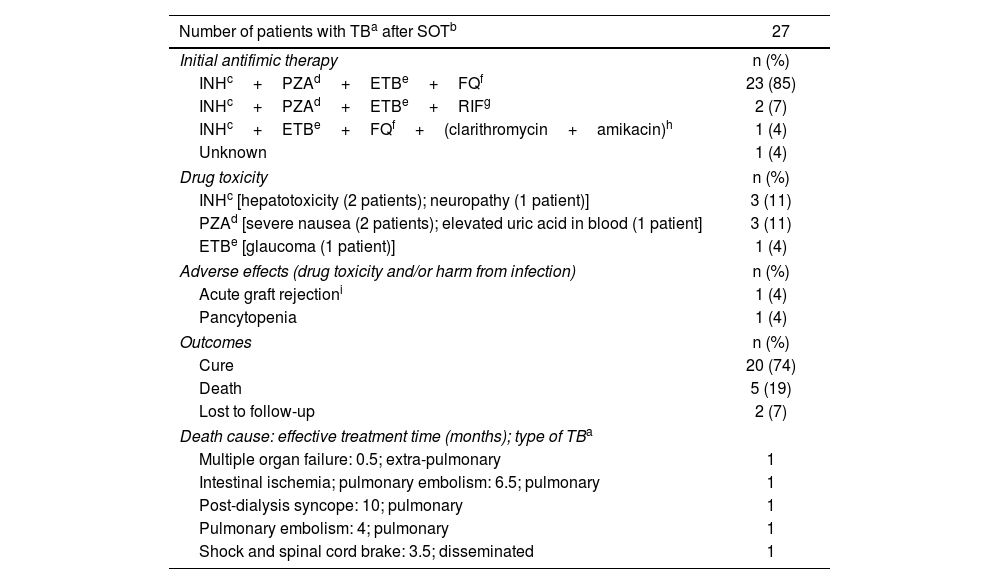

Antifimic therapy and outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Initial treatment was documented in 26 of out 27 patients. Twenty-four patients received an initial four-drug regimen without rifampin. Nineteen (79%) of them achieved clinical and microbiological cure, four (17%) died while on treatment, and one (4%) was lost to follow-up (Supplementary Table S1). Two patients received rifampin instead of fluoroquinolone in the initial four-drug scheme. In one of them, rifampin was replaced by levofloxacin after three months of torpid evolution; this patient died a month later due to pulmonary embolism. The other patient was lost to follow-up after four months of effective treatment (Supplementary Table S1). The use of rifampin in SOT recipients is complicated by its induction effect on different drug metabolizing enzyme systems, most notably the cytochrome P450, which decreases levels of calcineurin inhibitors and might lead to rejection of the graft9,13,14. However, most international guidelines recommend the use of this drug as part of the initial treatment due to its potent sterilizing activity5,11,14. Despite this fact, some reports describe the successful use of non-rifamycin-containing regimens for TB in SOT recipients1,15. A recent published review of TB in kidney and kidney-pancreatic recipients conducted in Argentina, showed that a therapy based on rifampin avoidance was successful, not only in terms of clinical cure, but also, in terms of graft function12. The use of rifampin-sparing regimens for over 16 years in our hospital suggests that this conclusion might be applicable to kidney, liver, heart, and lung recipients. However, multicenter and controlled clinical trials are desirable to standardize a promissory TB treatment in this specific group of patients. Another controversial point related to the therapeutic management of TB in SOT recipients is the optimal duration of the treatment. Although there is no consensus on this respect, few studies have suggested that a treatment of less than 9 months is associated with greater recurrence and mortality9,13. In the review by Radisic et al., most patients were treated for 12 months12. In our experience, patients suffering from pulmonary TB were treated for at least 12 months (only one patient received 10 months of treatment and achieved clinical and microbiological cure) and those with disseminated or extra-pulmonary forms were treated for 12–18 months (Supplementary Table S1).

Therapy and outcomes for active tuberculosis after solid organ transplantation.

| Number of patients with TBa after SOTb | 27 |

|---|---|

| Initial antifimic therapy | n (%) |

| INHc+PZAd+ETBe+FQf | 23 (85) |

| INHc+PZAd+ETBe+RIFg | 2 (7) |

| INHc+ETBe+FQf+(clarithromycin+amikacin)h | 1 (4) |

| Unknown | 1 (4) |

| Drug toxicity | n (%) |

| INHc [hepatotoxicity (2 patients); neuropathy (1 patient)] | 3 (11) |

| PZAd [severe nausea (2 patients); elevated uric acid in blood (1 patient] | 3 (11) |

| ETBe [glaucoma (1 patient)] | 1 (4) |

| Adverse effects (drug toxicity and/or harm from infection) | n (%) |

| Acute graft rejectioni | 1 (4) |

| Pancytopenia | 1 (4) |

| Outcomes | n (%) |

| Cure | 20 (74) |

| Death | 5 (19) |

| Lost to follow-up | 2 (7) |

| Death cause: effective treatment time (months); type of TBa | |

| Multiple organ failure: 0.5; extra-pulmonary | 1 |

| Intestinal ischemia; pulmonary embolism: 6.5; pulmonary | 1 |

| Post-dialysis syncope: 10; pulmonary | 1 |

| Pulmonary embolism: 4; pulmonary | 1 |

| Shock and spinal cord brake: 3.5; disseminated | 1 |

Data are presented as number of patients (percentage), n (%).

Another worrying point in TB treatment is drug toxicity. In this review, isoniazid and pyrazinamide presented the most frequent adverse effects. Additionally, one patient experienced acute graft rejection and another developed pancytopenia while on treatment. In these cases, it was not possible to differentiate between drug toxicity and harm from infection (Table 2). No adverse effects associated to long-term use of fluoroquinolones were documented.

Microbiological and clinical cure was achieved in 20 out of 25 (80%) patients (two patients were lost to follow-up) and crude mortality rate was 20% (5/25). Median (range) age of deceased patients was 60 (49–71) years; three (60%) of them were male (Supplementary Table S1). TB in SOT recipients shows a higher mortality rate than in immunocompetent patients with reported values as high as 30%14. In a recent review on more than 2000 cases of TB in SOT recipients, the overall mortality rate was almost 19% scaling to 25% among lung recipients1. In our study, it was not feasible to discriminate between crude or related mortality using the available data. Deaths occurred both at the beginning and near the end of effective treatment. None were considered associated with resistance to M. tuberculosis first-line drugs.

In summary, tuberculosis in SOT recipients is a significant opportunistic infection that frequently presents extra-pulmonary and disseminated forms, which represents a challenge for clinical diagnosis and treatment. The design of the current revision does not allow, and it is out of scope, defining the incidence of TB after SOT in our hospital. However, in various studies conducted in hospitals in Latin America, TB was diagnosed in 0.90–5.90% of SOT recipients13. Although the incidence of TB in SOT patients varies among different series, it is in accordance with the local prevalence of the disease11,13. In Argentina, there was an increase of 9.2% in reported cases of TB in the general population during 2024 with respect to 2023, showing that this infectious disease is a matter of concern4. This scenario also represents an important risk factor for exposure to M. tuberculosis in SOT candidates before and after transplant.

In our experience, Ziehl-Neelsen stain showed good sensitivity; however, invasive sampling was needed to improve the diagnosis. Unfortunately, molecular methods were not routinely available during the period of study, as these would have been an advantage in terms of speed and sensitivity. The World Health Organization recommends several of these tests and proposes them as first-line options for TB diagnosis10. Broader and low-cost access to molecular methods is required to increase sensitivity and reduce diagnosis delay.

Our study presents some limitations due to its retrospective observational design and the limited number of patients involved. Nevertheless, it summarizes the experience of a specialized SOT center in Argentina and contributes to describing the epidemiology of TB in lung, kidney, heart and liver transplant recipients.

A nationwide prospective study is needed to expand knowledge about tuberculosis in this specific population.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.

Dedicated to the memory of Dr. Claudia Beatriz Nagel who was both the head of the Infectious Diseases Department and a clinical doctor committed to her patients.

The authors are grateful to Dr. Mercedes Valerio for a critical reading of the manuscript and to Haydée Ramos for the spelling check of the English text.