Hepatitis A virus (HAV) has a low endemic circulation pattern in Argentina. Clinical cases mainly occurred in susceptible young adults, with recent outbreaks reported. The aim of this study was to provide updated information on the HAV immune status of the adult population from Central Argentina. A retrospective analysis was conducted, recording the results of anti-HAV IgG in 4235 samples of individuals without prior vaccination from Córdoba, Argentina (2019 and 2022). Epidemiological data recorded included sex, age, HIV status and income level. The overall prevalence of anti-HAV was 70.1%, increasing with age as follows: 52.6% among the 18–25-year-old group, 53.8% in 26–35-year-old young adults, 67.4% in 36–45-year old adults, and >80% in the >46-year-old group. Moreover, prevalence was associated with low-income populations and was significantly higher among female patients (p<0.0001). Considering the high proportion of young adult individuals susceptible to HAV infection identified, along with evidence of HAV circulation in the region – which can be easily introduced by unvaccinated immigrants or travelers from medium/high endemic countries – and the existence of a safe, efficient vaccine, we strongly recommend further investigating HAV immunity in individuals over 18 years old in our region. For those testing negative, vaccination is recommended.

El virus de la hepatitis A (HAV) presenta un patrón de baja endemicidad en Argentina. La notificación de casos clínicos se produce especialmente en adultos jóvenes susceptibles, población en la que recientemente se han reportado brotes. El objetivo de este estudio fue proporcionar información actualizada sobre el estado inmunitario frente al HAV en la población adulta del área central de Argentina. Se realizó un análisis retrospectivo que registró los resultados de IgG anti-HAV en 4.235 muestras de personas sin vacunación previa de Córdoba, Argentina (años 2019 y 2022). Se consignaron como datos epidemiológicos el sexo, la edad, el estado serológico respecto al HIV y el nivel de ingresos. La prevalencia general de anti-HAV fue del 70,1%. Esta aumentó con la edad de la siguiente manera: 52,6% en el grupo de 18 a 25 años; 53,8% en adultos jóvenes de 26 a 35 años; 67,4% en adultos de 36 a 45 años y >80% en el grupo >46 años. La seroprevalencia se asoció con la población de bajos ingresos y fue significativamente mayor en mujeres (p<0,0001). Considerando la alta proporción de adultos jóvenes susceptibles de padecer la infección por el HAV, sumado a la evidencia de circulación del virus en la región (probablemente introducido por inmigrantes no vacunados o viajeros procedentes de países con endemicidad media/alta) y a la existencia de una vacuna segura y eficaz, se recomienda intensificar los estudios de inmunidad frente al HAV en personas mayores de 18 años en nuestra región. En caso de ser negativos, debería indicarse la vacunación.

Hepatitis A (HA) is a vaccine-preventable liver disease caused by the single-stranded RNA hepatitis A virus (HAV), with 1.5 million symptomatic HAV infections occurring every year worldwide. It is primarily transmitted through the fecal–oral route, likely occurring through direct contact with an infected person, or indirectly through contaminated food or water12. Although the risk of infection in laboratory workers is generally considered low, prevention is achieved by implementing appropriate safety measures and through vaccination19.

HAV infection can result in a spectrum of liver diseases and systemic manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic infection and self-limited hepatitis to acute liver failure. Severe outcomes occur especially at increasing ages and in older adults30,37.

South America was considered a high endemicity area of HA in the past; however, in recent years, the HAV circulation scenario has been changing10. The improvement of hygienic measures, the introduction of the vaccine, the globalization process, and traveling are significant factors contributing to epidemiological changes. In countries where socioeconomic and sanitary conditions and prevention measures have not improved, the virus continues to circulate with high levels of endemicity. On the other hand, in countries where HAV immunization programs have been implemented, the number of cases among young adults seems to be increasing, projecting a new epidemiological pattern of the disease in the region26. Such is the case of Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay1,26. After a decade of progressive decrease in HAV cases in South America, outbreaks mainly affecting young adult men who had sex with men (MSM) were registered in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile since 20175,14,17,24,27,28.

In Brazil, an 8- to 14-fold increase in the incidence of cases was observed in Rio de Janeiro state and São Paulo city, mostly among MSM in the 20–29 age range5,17,24. Similarly, in Chile, an outbreak of 2227 confirmed cases was registered. Furthermore, an increase of 168% in HAV cases in this group was recorded compared to 201628. In the central region of Argentina, Mariojoules et al.14 reported an outbreak affecting MSM with a median age of 31.9 years (range 21–55 years) with a 19- to 23-fold increase in the incidence of cases previously reported in Córdoba province (Central Argentina)20.

This unexpected increase in cases likely reflects a decline in immunity in the young adult population due to reduced natural contact with the virus, giving rise to a favorable scenario for outbreaks in the post-vaccine era. In this sense, there is a lack of updated information regarding the seroprevalence in the general population in countries undergoing vaccination programs, including different age groups26. A recent study by Flichman et al.7, reported a low prevalence of anti-HAV (<60%) among adults between 27 and 52 years old in a cohort from the city of Buenos Aires. In Central Argentina, Yánez et al.38 reported, prior to the last outbreak, a decrease in specific antibody prevalence among young adults between 20 and 35 years old (∼55%) after five years of the HAV vaccine introduction in the immunization schedule. Coincidentally, a study conducted in Chile23 shows an overall 10% seroprevalence decrease between two periods 10 years apart: an anti-HAV IgG detection frequency of 80% was detected in 2004–2006 vs. 67% in 2014–2016. This finding was also reflected in an abrupt decline in young adults’ immunity.

In Córdoba province during 2022 and recently, in 2024–2025, increases in HA case notifications were again observed in unvaccinated young adults. Simultaneously, environmental studies demonstrated RNA-HAV presence in local wastewaters, evidencing its continuous circulation in the population6,18. However, there is no updated data on the serological prevalence of HAV in the adult population in our region.

Given this background, this study aimed to provide updated information on the HAV immune status of the adult population in the central region of Argentina 17 years after the official introduction of the one dose-vaccine in 2005. This will contribute to a better understanding of the disease evolution in the post-vaccination era and help implement specific public healthcare actions.

Materials and methodsStudy populationA cross-sectional, observational, and retrospective study was conducted in serum samples from adult individuals (>18 years old), who attended public (PuHC) or private healthcare centers (PrHC) in Córdoba (the second most populated inland province of Argentina, with 1505250 inhabitants)9 for routine check-ups during 2019 and 2022.

Age and gender data were obtained from medical and laboratory records. Individuals were classified into five groups according to age (18–25 years old, 26–35 years old, 36–45 years old, 46–55 years old, and older than 56 years old). HIV serological status data could only be obtained from public healthcare centers. Additionally, individuals were classified into three groups. Group 1: HIV (+) adult individuals who attended PuHC, Groups 2 and 3: adult individuals from the general population who attended PuHC and PrHC, respectively.

Considering the Argentine health system, medical care in private or public centers can be used as a surrogate indicator of the socioeconomic condition of the population. Thus, healthcare in private centers is associated with middle/high-income populations that have access to social security or health insurance, and enjoy better sanitary conditions, mainly workers in the formal economy. On the other hand, in public healthcare centers, government entities provide free health services to anyone who requests it, mainly to low-income populations without social security and the financial means to pay healthcare, usually living in precarious sanitary conditions3.

Data was obtained in a non-binding, anonymous manner and the study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, amended most recently in 2008) of the World Medical Association, and in accordance with specific local ethical regulations (Legislature of the Province of Cordoba, 2009). The Research Evaluation Committee of the Institute of Virology “Dr. José María Vanella” (Ex-2024-00072937) approved to perform this study.

Serological testIn Groups 1 and 2, anti-HAV antibodies were detected in a 25μl serum sample, using a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA, Abbott, Germany) on the Architect™ automated system. The test allows for the qualitative detection of IgG anti-HAV antibodies. The system calculates a result based on the ratio of the sample RLU to the cut-off RLU (S/CO) for each specimen and control. An S/CO greater than one was considered reactive.

In Group 3, anti-HAV antibodies were detected in a 12μl serum sample, using a competitive electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA, Roche, Switzerland) on the Cobas™ e 801 automated system. The test allows for the qualitative detection of total anti-HAV (IgM and IgG) antibodies. The sample result is indicated in the form of a cut-off index (COI: sample signal/cut-off). A COI lower than one was considered reactive.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were conducted using Stata 17.0 software. A descriptive and exploratory analysis was carried out to calculate the frequencies of the variables of interest. The demographic categorical variables that characterized the sample under study were expressed in proportions. To identify differences among the groups, a difference in proportions was used. A chi-square test was applied to verify associations between variables. Risk factors associated with HAV infection and sociodemographic characteristics were identified by using multiple logistic regression models. Statistical significance was established at p<0.05.

ResultsA total of 4235 plasma samples were studied, of which 1575 corresponded to Group 1 [984 men and 591 women, mean age 37.6 (±10.8) years old]. The remaining 2660 samples belonged to individuals from the general population: 1248 corresponded to Group 2 [657 men and 591 women, mean age: 38.4 (±13.9) years old], and 1412 corresponded to Group 3 [757 men and 655 women, mean age 43.5 (±15.1) years old].

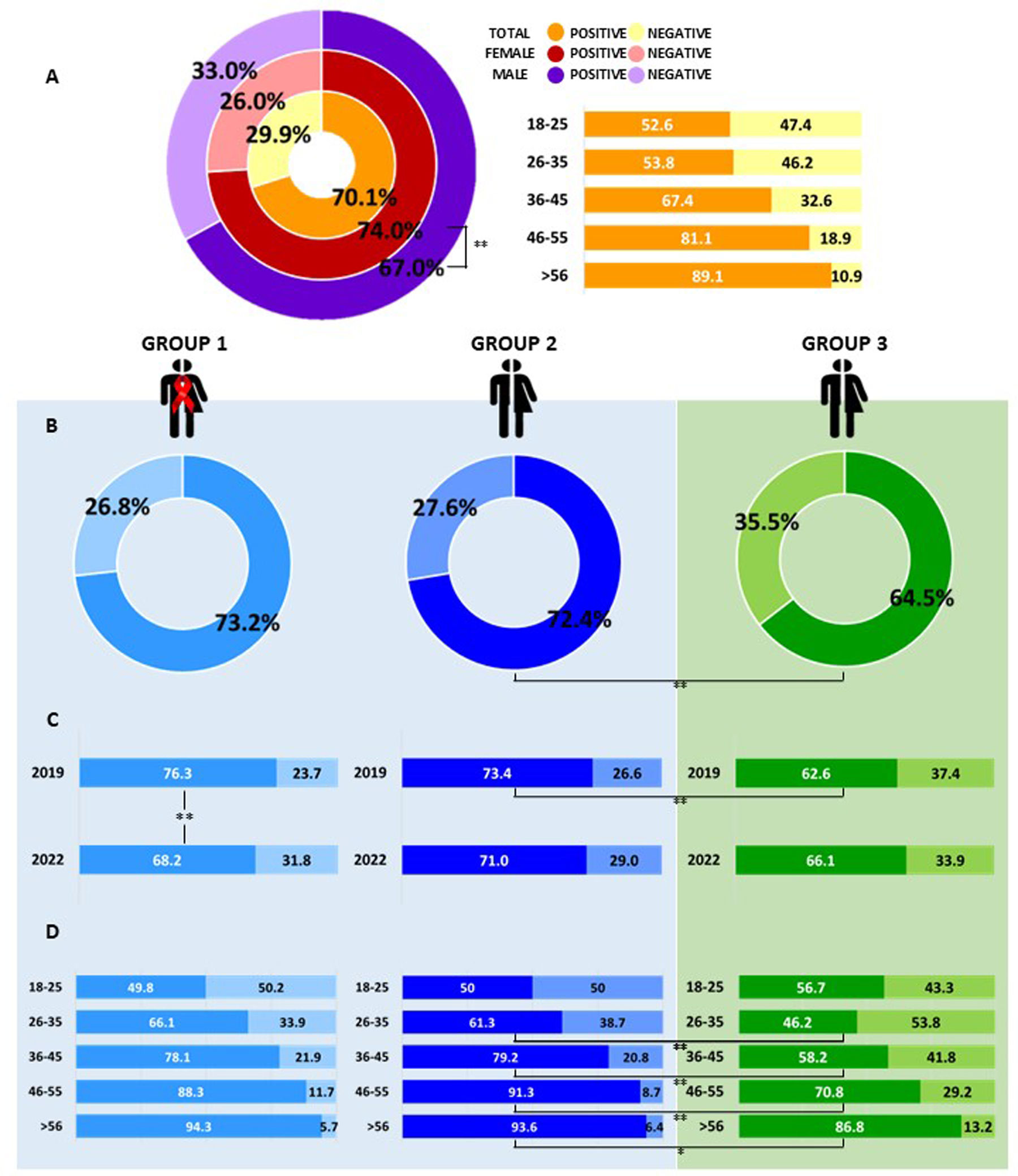

The overall prevalence of anti-HAV antibodies was 70.1% (2967/4235). Anti-HAV prevalence was significantly higher in female patients than in male patients: 74.0% [female: 1360/1837, mean age 40.4 (±12.4) years old] vs. 67.0% [male: 1607/2398, mean age 40.4 (±12.2) years old] (p<0.001) (Fig. 1A).

Anti-HAV prevalence in individuals from the central region of Argentina. (A) Global prevalence value in the entire population studied, discriminated by sex and age group. (B) Anti-HAV prevalence obtained in the studied groups: Group 1: HIV (+) individuals attending public healthcare centers (low-income population), Group 2: individuals from the general population attending public healthcare centers (low-income population), Group 3: individuals from the general population attending private healthcare centers (middle/high-income population). (C) Anti-HAV prevalence by year (2019 and 2022) in the studied groups. (D) Anti-HAV prevalence by age range in the studied groups. *p<0.05 **p<0.001.

The total prevalence of anti-HAV among the general population (excluding Group 1 HIV positive patients) was lower in individuals from Group 3 (middle/high-income population) [64.5% (911/1412)] compared to those from Group 2 (low-income population) [72.4% (903/1248)] (p<0.001) (Fig. 1B). When studied over the years, this difference was registered in 2019 [Group 2: 73.4% (503/685) – Group 3: 62.6% (391/625) (p<0.001)], but was not observed in 2022 [Group 2: 71.0% (400/563) – Group 3: 66.1% (520/787) (p=0.053)] (Fig. 1C) (Supplementary Table 1).

The frequency of anti-HAV detection was higher among women between both types of healthcare centers [Group 2: female 74.6% vs. male 70.3% (p=0.09); Group 3: female 68.2% vs. male 61.3% (p<0.05)] and remained stable in both sampling periods (Group 22019 73.4% vs. Group22022: 71.0% (p=0.35); Group 32019: 62.6% vs. Group 32022 66.1% (p=0.17) (Supplementary Table 1).

There was no significant difference regarding anti-HAV seroprevalence and HIV serostatus [Group 2: 72.4% vs. Group 1: 73.2% (p=0.61)] (Fig. 1B) (Supplementary Table 2). In Group 1, higher frequency of anti-HAV antibody detection was observed in 2019 (76.3%) vs. 2022 (68.2%) (p<0.001) (Fig. 1B) (Supplementary Table 2).

Globally, the prevalence of anti-HAV increased with age: 52.6% among the 18–25-year-old group, 53.8% in young adults aged 26–35 years, 67.4% in 36- to 45-year-old adults, and >80% in the group aged 46 years and older (Fig. 1A). A similar trend in anti-HAV prevalence by age group was observed among Groups 1 and 2, and no statistically significant differences were found between them (Fig. 1D). In the general population, depending on the healthcare center attended (Group 2 vs. Group 3), the differences throughout the age groups were highlighted, showing homogeneity only for the 18–25-year-old age groups (p=0.16) (Fig. 1D). Anti-HAV was significantly higher between ages 26–35, 36–45, 46–55 (p<0.001) and >56 years (p<0.05) in Group 2 (61.3–93.6%) vs. Group 3 (46.2–86.8%) (Fig. 1D).

DiscussionIn recent years, because of sanitary and socioeconomic improvements in some areas of the world, including South America, and due to the introduction of the vaccine, the age distribution of HAV infection has shifted from childhood to older age groups, which resulted in an increase of symptomatic cases. Consequently, outbreaks in young adults have been reported in these new epidemiological scenarios worldwide.

Argentina was the first country in South America to introduce the HAV vaccine in its official vaccination schedule in 200536. Since the HAV vaccine was introduced only for one-year-old children, we assume that the adults included in our study were mostly unvaccinated. Furthermore, the serum samples analyzed belonged to individuals attending public and private healthcare centers assuming that they belonged to different socioeconomic levels, according to the classification of the Argentine Health System3. Generating updated information on the HAV serostatus in the adult population, 17 years later, improves our knowledge of the current population immunity profile to focus on local and regional control, preventive recommendations, and measures.

As expected, the prevalence of anti-HAV antibodies found during this study exhibits a pattern of low endemicity in the central region of Argentina. In line with previous studies in our region, the influence of the socioeconomic level on the seroprevalence obtained was also observed, detecting higher anti-HAV levels among participants from lower social strata2,31. The prevalence in individuals belonging to low-income populations was 8% higher than that obtained in individuals belonging to middle/high-income populations, and this trend was greater in adults and young adults (15–20%), confirming previous studies8,11,38,40, and showing that differences in sanitary hygiene conditions still exist between populations in our area, which would influence the occurrence of infections such as hepatitis A.

Regarding the prevalence by age groups, we found an increasing trend, as described in a previous study by Yánez et al.38 in the same geographical area (10 years ago), with a prevalence exceeding 80% in adults >46 years old. This has been previously described, and was associated with the time of exposure to the virus as well as the fact that older individuals may have been exposed to poorer sanitary conditions11,31.

Vaccination regulations establish that 95% of the population must be immunized, and epidemiological surveillance (through the measurement of HAV antibodies) should be conducted to prevent and anticipate the occurrence of large hepatitis A outbreaks13. However, field studies conducted in the United States, Alaska, and Europe have demonstrated that vaccination against HAV can prevent and/or control an outbreak if 70–80% of the susceptible population is vaccinated16,25,29,34. In this context, the concept of necessary immunity, whether natural or acquired through vaccination, can be extended to prevent the transmission of a pathogen and analyze its significance at the antibody prevalence level in the general population4,39. In Argentina, hepatitis A vaccination coverage fell slightly below 80% in 2020. In 2021, there was an improvement in national vaccination coverage that exceeded pre-pandemic values, and during 2022, stable coverage was maintained, similar to the previous year (∼87%)21. In our study, a prevalence of anti-HAV below 60% was observed among individuals from middle/high-income groups under 45 years of age, while in low-income populations, coverage of population immunity was found to be below 70% among individuals under 35 years of age. These data evidence that population immunity in young adults is lower than the recommended 70%, showing a favorable scenario for the occurrence of outbreaks, particularly among adults, with more chances of symptomatic infections. In this context, an abrupt increase in HA cases was registered in Argentina at the end of 2024 and beginning of 2025, with most cases occurring in young adult men18.

If vaccination coverage of the official program continues to increase, in the future it is expected to reach an adequate coverage level of ∼90% of humoral immunity in the vaccinated population. Subsequent studies will confirm whether the single-dose scheme is still effective over time, as has been demonstrated to date32,33,35, or evaluate the need for a booster dose.

Hepatitis A is a disease closely linked to socioeconomic conditions, access to drinking water, and adequate excreta disposal. A deficiency in these conditions generates a delicate situation for susceptible groups and a greater circulation of the virus. The improvement in hygienic-sanitary conditions in recent years has reduced exposure to HAV in childhood, leading to an increase in the number of adults who were never exposed to the virus in childhood and therefore lack immunity, particularly among those from private healthcare centers (individuals with medium/high socioeconomic status). Implementing an immunization program without boosters only for younger children, when many young adults may be above the cut-off age at which vaccination was introduced, raises the risks of outbreaks in these susceptible populations. In Argentina, young people up to 18 years of age accessed vaccinations with ∼90%21 coverage. For this reason, young adults are currently the most susceptible group to HAV infection and the most likely to develop clinical cases.

With regard to travelers to and from endemic areas, it is known that they currently constitute a risk for viral dissemination. Thus, susceptible individuals who travel to an endemic area can become infected and return to their place of origin causing its dissemination. In addition, a person traveling from an endemic area to a non-endemic area can transport the virus and if they come into contact with susceptible individuals, they can pose a risk to them. As a result, the WHO recommends antibody testing and/or vaccination to prevent an increase in cases and/or outbreaks. In Argentina, it is not mandatory to require hepatitis A vaccination for adult travelers coming from endemic areas, nor to control the immunity of individuals traveling to endemic areas. This fact poses a constant risk for the introduction of the virus and other variants to our region. Furthermore, our group recently demonstrated that, despite vaccination at one year of age, the virus continues to circulate constantly, which was evidenced by HAV-RNA detection in sewage and recreational waters of Córdoba, being a potential risk of infection for susceptible individuals6,15. These findings should alert the healthcare system. One effective measure to implement would be the anti-HAV IgG screening, especially for immunosuppressed individuals, those who are HIV (+), or those with comorbidities; vaccination should be recommended for individuals who test negative. In this regard, the Ministry of Health of Argentina in its recommendations includes individuals living with HIV as a target group for vaccination within the national immunization program, based on medical indications22. However, this is not a routine practice among healthcare professionals in our region. This was demonstrated in the HAV outbreak that occurred in 2017 among MSM, since a high percentage of them were HIV (+), evidencing the lack of immunity, and, consequently, the failure to recommend vaccination in this group14. Our results showed that in individuals living with HIV, from low socioeconomic conditions, the frequency of anti-HAV was similar to that found in the HIV (−) population from the same socioeconomic environment. In these groups, although the global prevalence of anti-HAV was >70%, the coverage of humoral immunity in individuals under 35 years old was below 66%, showing that 34% remain susceptible and could become infected under the current conditions of viral circulation.

The higher anti-HAV prevalence observed in HIV (+) individuals in 2019 compared to 2022 may be associated with these factors: (a) the population tested in 2019 may have been in contact with individuals related to the outbreak and could have increased the percentage of immunity; (b) immunity in that group may have increased due to stronger post-outbreak national recommendations for vaccination in susceptible groups and/or improved access to the vaccine, which may have relaxed over time (as shown by the decline in anti-HAV prevalence in 2022); or (c) the implementation of stricter hygiene and health measures, along with the quarantine implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) (which restricted mobility and person-to-person contact), may have resulted in reduced contact with the virus and a decrease in the anti-HAV prevalence in 2022. In this context, it is essential to continue with the vaccination official policy; however, epidemiological surveillance and catch-up vaccination for adolescents and young adults should be improved, particularly, among immunosuppressed individuals, who had free access to hepatitis A vaccination.

ConclusionsBased on: (a) the recent increase in hepatitis A cases in adults, (b) the evidence of continuous environmental circulation of HAV in the region, (c) the low proportion of anti-HAV immune individuals observed among young adults, (d) the fact that the disease severity increases with age, (e) the existence of a safe, efficient and effective available vaccine, and (f) the free availability of the vaccine for immunosuppressed individuals, we strongly recommend delving deeper into the study of HAV immunity in individuals >19 years old in our region. If they test negative, vaccination is recommended. Moreover, the communication of prevention strategies should be improved, using social media to raise awareness among both healthcare personnel and the general population. This will help to mitigate viral dissemination in regions with changing epidemiological scenarios in the post-vaccine era.

FundingThis research has not received any specific grant from agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sector.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.