In the last few decades, the emergence of several infectious diseases has increased. Mosquitoes are the most important vectors due to their role in transmitting several pathogens, such as dengue, chikungunya and Plasmodium spp. Recently, mosquitoes have been suspected of transmitting Rickettsias, another emerging pathogen. However, their role in the transmission of this agent remains unclear. In this study, we report the detection of a Rickettsia spp. in Coquillettidia venezuelensis mosquitoes collected from Corrientes Province, Argentina. The phylogenetic analyses show that this Rickettsia is related to Rickettsia felis, and the ompB sequence shows high homology with Rickettsia tillamookensis. The evidence of the detection of Rickettsia in mosquitoes shows that several infectious diseases could be transmitted by mosquitoes, and the interaction between them is important to investigate. More studies should be done in order to analyze the impact on public health.

En las últimas décadas, la aparición de enfermedades infecciosas ha ido en aumento. Los mosquitos son los vectores más importantes debido a que actúan como transmisores de diversos patógenos, entre ellos, dengue, chikunguña y Plasmodium spp. Recientemente, se ha sospechado que los mosquitos también pueden transmitir rickettsias, otro patógeno emergente. Sin embargo, el papel de los mosquitos en la transmisión de este agente es aun poco claro. En este estudio informamos la detección de Rickettsia spp. en la especie de mosquito Coquillettidia venezuelensis, de ejemplares capturados en la provincia de Corrientes, Argentina. Este representa el primer reporte de detección de ADN de rickettsia en el país. El análisis filogenético indica que esta rickettsia está relacionada con Rickettsia felis y la secuencia del gen ompB muestra una alta homología con Rickettsiatillamookensis. La detección de rickettsia en los mosquitos sugiere que estos insectos podrían ser los vectores de múltiples agentes causales de enfermedades infecciosas, lo que resalta la necesidad de investigar la interacción entre ellos. Se deben realizar más estudios con el fin de analizar el impacto de este hallazgo en la salud pública.

In recent decades, the impact of several infectious diseases has increased. Their emergence may be attributed to factors such as increasing urbanization, changes in land use, global warming, increased human–animal contact, and the expanded global distribution of their vectors37.

Rickettsiales are a group of bacteria that are obligate intracellular, Gram-negative microorganisms, primarily vectored by arthropods. Their importance in public health lies in the fact that they can cause severe human diseases, such as anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, and rickettsioses. Ticks have been considered the most important vectors of Rickettsia; however, other ectoparasites, such as fleas, mites, and midges, also act as vectors for different Rickettsia species7.

Rickettsia is responsible for emerging and re-emerging diseases worldwide30. In nature, Rickettsia bacteria are spread by both transstadial and transovarial (i.e., vertical) transmission in their arthropod hosts, or by horizontal (co-feeding) transmission through an infected vertebrate. In Argentina, human cases of Rickettsia have been reported, including R. rickettsii and R. parkeri26,27. Additionally, R. massiliae has been detected in ticks5, and R. asembonensis and R. felis have been recorded in fleas1,17,20,21,29.

Mosquitoes are among the most important insects in terms of public health; their blood-feeding behavior is a critical determinant of pathogen transmission. It is well known that mosquitoes are the primary vectors of several arboviruses, such as dengue, chikungunya, and West Nile virus, and are the major vectors of Plasmodium spp., the causative agent of malaria33. Moreover, in recent years, Rickettsia have been detected in mosquito samples12,18,19,31,32,36. However, the role of mosquitoes in the transmission of Rickettsia and their potential impact on public health remain unclear. Additionally, no studies on Rickettsia involving these insects have been conducted in Argentina.

In order to gather more data on Rickettsia species in mosquitoes, the objective of this study was to analyze the presence of Rickettsia spp. in mosquito samples from northeastern Argentina using molecular biology methods.

Materials and methodsMosquito collection and identificationIn November 2019, mosquitoes were collected in Tabay, Corrientes (28°18′27″S, 58°17′13″W) during an entomological surveillance for yellow fever virus. This town is located 140km from the city of Corrientes and has a population of 1700 inhabitants (Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas de la República Argentina, 2010). Manual captures were performed over three consecutive days, during the day, with morning and afternoon sessions lasting four hours (from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m. and from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m., respectively). Mosquitoes were stored in cryovials containing liquid nitrogen and shipped to the Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Virales Humanas (INEVH-ANLIS) laboratory. Mosquito processing was performed as previously described by Goenaga et al.11. Briefly, upon arrival at the laboratory, the specimens were sorted by species and day of capture under a stereoscopic microscope on a chilled table. Specimens were morphologically identified using a dichotomous key developed by Darsie5.

Pools were assembled with mosquitoes of the same species captured on the same day, and each was homogenized in a microtube containing a 3mm tungsten bead and 1ml of phosphate-buffered saline solution with 0.75% bovine albumin, penicillin (100units/ml), and streptomycin (100μg/ml) for 1min at 20 cycles per second using a Bead Ruptor 24 Elite (OMNI International, Kennesaw, Georgia, USA). Homogenates were clarified by centrifugation at 5000×g for 10min at 4°C.

Samples were processed using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) and eluted into final volumes of 60μl.

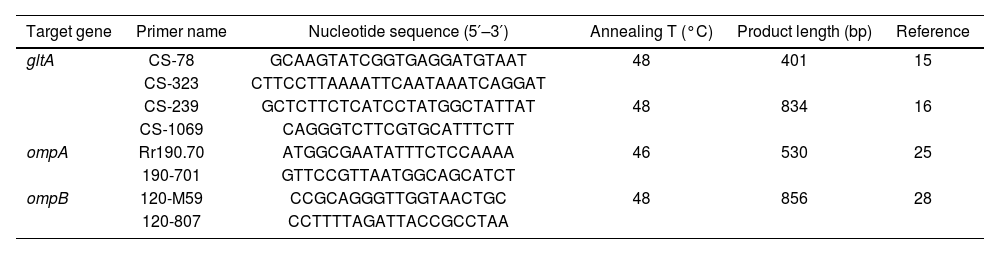

The presence of Rickettsia spp. was screened by a specific PCR of the following genes: citrate synthase (gltA: 401 bp fragment and 834 bp fragment), outer membrane protein A (ompA), and outer membrane protein B (ompB) genes (Table 1). For the amplification, the PCR program started with an initial denaturation for 2min at 98°C, followed by 40 cycles (94°C for 15s, gene-specific annealing at 48°C for 30s, and 74°C for 30s), and a final extension step at 72°C for 5min (Table 1). The PCR reaction was set to a final volume of 20μl, containing: 25–100ng of template DNA, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.2μM of each primer, 0.2mM of each dNTP, 1X reaction buffer, 0.5U of Taq Platinum DNA polymerase, and ultrapure sterile water to reach the final volume. For each reaction, a negative control (5μl of molecular-grade water) and a positive control (5μl of DNA belonging to R. prowazekii) were included. PCR products were electrophoresed through a 2% agarose gel, stained with 10000× SYBR® Safe (Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon, USA), and examined by LED transillumination.

Genes, primer names and sequences, and PCR amplification conditions used for Rickettsia detection.

| Target gene | Primer name | Nucleotide sequence (5′–3′) | Annealing T (°C) | Product length (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gltA | CS-78 | GCAAGTATCGGTGAGGATGTAAT | 48 | 401 | 15 |

| CS-323 | CTTCCTTAAAATTCAATAAATCAGGAT | ||||

| CS-239 | GCTCTTCTCATCCTATGGCTATTAT | 48 | 834 | 16 | |

| CS-1069 | CAGGGTCTTCGTGCATTTCTT | ||||

| ompA | Rr190.70 | ATGGCGAATATTTCTCCAAAA | 46 | 530 | 25 |

| 190-701 | GTTCCGTTAATGGCAGCATCT | ||||

| ompB | 120-M59 | CCGCAGGGTTGGTAACTGC | 48 | 856 | 28 |

| 120-807 | CCTTTTAGATTACCGCCTAA |

Conventional PCR products (gltA, ompA, and ompB genes) were purified using the QIAquick Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Both strands of the purified DNA were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sanger sequencing was performed using an ABI PRISM 3500 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Sequences were edited using the BioEdit program13. A homology analysis was conducted using the BLAST algorithm (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) against the GenBank nucleotide database to elucidate the identity of each sequence. Finally, the Clustal-W method was used for alignment (available at http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html).

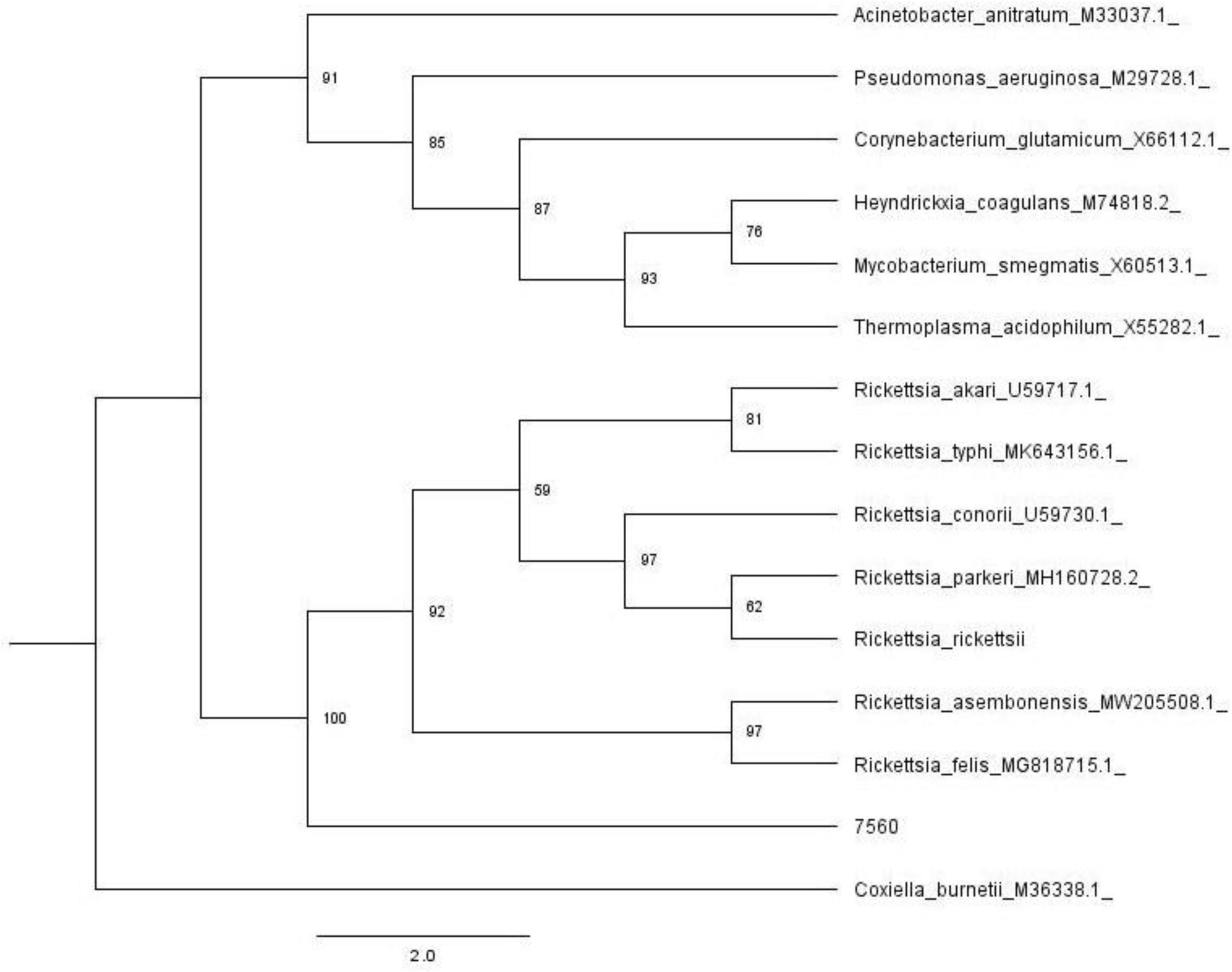

Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method for both the gltA and ompB genes. For the phylogenetic analysis, the IQ-TREE web server was used35. The best-fit model for gltA was TIMe+G4, and for ompB, TVM+F+G4, both chosen according to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)14. The confidence levels of the nodes were determined using bootstrapping with 1000 replicates. Tree topology was reconstructed using FigTree software24.

ResultsWe captured 357 individual mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) belonging to the genera Aedes (0.28%), Anopheles (0.28%), Coquillettidia (59.6%), Mansonia (15.4%), Psorophora (20.7%), Sabethes (0.84%), and Wyeomyia (2.8%).

Of all the pools (25 in total), only one tested positive for both the gltA and ompB genes by PCR. No amplification was detected using primers targeting the ompA gene. Since the gltA gene is highly conserved, its amplification only confirms the presence of the genus; therefore, to confirm the species identity, the ompB gene was sequenced.

A 750 bp fragment corresponding to the gltA gene and a 780 bp fragment corresponding to the ompB gene were sequenced and deposited in the GenBank nucleotide database under accession numbers PQ488464 (gltA) and PQ488463 (ompB).

The positive pool was composed of 39 individuals from Coquillettidia venezuelensis (Theobald, 1912). For species confirmation, a PCR targeting the cytochrome c oxidase 1 (COI) gene was performed using the primer pairs from Folmer et al.8: LCO1490 (5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′) and HCO2198 (5′-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′), which were used to amplify the ∼658 bp fragment of the COI gene. The sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession number PQ315765.

For the ompB gene, nBLAST analysis indicated identities of 93.94% (query cover: 100%; e-value: 0) with Rickettsia tillamookensis and 91.78% (query cover: 100%; e-value: 0) with R. felis, respectively.

In Figure 1, we show the results of the phylogenetic analysis (ML) using a 750 bp fragment from the citrate synthase gene (gltA), and Figure 2 shows the analysis using a 780 bp fragment from the ompB gene sequences. These analyses demonstrate that the sequences obtained in this study belong to Rickettsia (Fig. 1). The ompB gene sequence analysis shows that it clusters with R. felis and R. assembonensis, but not with R. tillamookensis, despite the high identity.

In this study, we report the presence of Rickettsia related to R. tillamokensis and R. felis in one pool of mosquitoes belonging to Coquillettidia (Rhynchotaenia) venezuelensis (Theobald, 1912), collected in Corrientes province, Argentina. This is the first detection of Rickettsia DNA in mosquitoes in Argentina.

The genus Rickettsia comprises Gram-negative bacteria that are obligate intracellular pathogens. It currently contains 32 species, divided into five phylogenetic groups: the Spotted Fever group (SFGI and SFGII), with the SFGI Rickettsiae group containing 24 species (e.g., R. conorii, R. massiliae, R. rickettsii), and the SFGII Rickettsiae group (also referred to as the transitional group, TRG), which includes five species (e.g., R. felis and R. australis); the Typhus group (TG), which includes R. prowazekii and R. typhi; the Canadensis group (CG), which includes R. canadensis; and the Bellii group (BG), which includes R. bellii7. In our study, we detected a Rickettsia related to the TRG, which includes R. felis, R. australis, R. asembonensis, and R. tillamookensis (Fig. 2)10.

In this study, we detected DNA belonging to Rickettsia (94% identity with R. tillamookensis and 92% identity with R. felis) in the mosquito species C. venezuelensis, which showed the highest abundances in the sampling conducted in the study area. This species is an aggressive and zoophilic mosquito. Its distribution in Argentina includes Northeast of Argentina, in the ecoregion of humedal (wetland) of Corrientes province4. It breeds in natural and permanent water containers, such as swamps, ponds, and lakes. Mayaro (Togaviridae) and Oropouche (Orthobunyavirus) viruses have been isolated from this species2,3. Furthermore, it has been reported as a vector for Eastern Equine Encephalitis (Togaviridae)9. This mosquito species is characterized by its daytime activity and strong preference for human hosts34. This condition could increase the health significance of the Rickettsia detected in terms of human transmission.

Rickettsia tillamookensis was recently characterized by Gauthier et al.10. This new Rickettsia species was detected in 1967 and several isolations and detections from ticks have since been reported. Recently, in 2021, as a result of whole genome sequencing of the original type strain (Tillamook 23T), it was revealed that this microorganism is a unique transitional group of Rickettsia species10. Experimental and historical observations suggest that R. tillamookensis could be pathogenic to human hosts22. Paddock et al.22 isolated R. tillamookensis from the tick Ixodes pacificus, in both adults and nymphs, suggesting that it is likely transmitted transstadially in nature. However, it should be noted that the role of mosquitoes as Rickettsia vectors remains unclear. Further studies should be conducted to evaluate vectorial competence and capacity.

In the phylogenetic analysis using ompB sequences (Fig. 2), our strain formed a distinct clade closely related to R. felis and R. asembonesis. Only a few sequences of R. tillamookensis are available in GenBank: two from complete chromosomes and three from the 16S ribosomal RNA. This limited sequence data may account for the difficulty in aligning with this Rickettsia species. However, it is important to note that the tree topology could change if additional R. tillamookensis sequences become available.

On the other hand, R. felis is another microorganism with zoonotic potential. Several authors have detected R. felis worldwide in fleas, and there are also reports of human cases associated with this agent23. However, in Argentina, despite several reports of R. felis detection, there are no reports in patients, and it is possible that the prevalence of the infection is underestimated. Healthcare professionals should be alerted to the possibility of infection with R. felis among their patients. The first detection of R. felis in mosquitoes was made by Socolovschi et al.31. Following that, Guo et al.12 reported the presence of Rickettsia species (R. japonica, R. sibirica, and R. monacensis) in adult mosquitoes using groEL sequences. In addition, R. japonica, R. sibirica, and R. monacensis were detected in all life stages (egg, larva, pupa, and adult). These data show the presence of several Rickettsia species; however, there is no evidence of the role mosquitoes play in transmission.

A novel Rickettsia species was detected in Anopheles mosquitoes in China, showing high similarity to R. felis18. In the phylogenetic analysis, our strain did not align with this new Rickettsia. This result suggests that it could represent a new Rickettsia species also related to R. felis, but further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

In order to determine the role of mosquitoes as vectors, one approach should be to isolate the bacterium from the saliva or salivary glands of specimens from wild-caught mosquitoes. Additionally, the infection of mosquitoes following experimental feeding on a bacteremic host, as well as the transmission of bacteria to a vertebrate through the bite of a mosquito, has been demonstrated. Dieme et al.6 infected Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes orally with R. felis and reported the transmission potential of R. felis 15 days post-infection, both via salivation and by detecting R. felis in mice after feeding on mosquitoes that had been previously infected. However, there was no report of vertical transmission, which suggests that horizontal transmission occurs in nature.

Overall, the studies indicate that mosquitoes may play a role in the transmission of several species of Rickettsia. However, the epidemiological significance of this finding remains uncertain. The detection of Rickettsia in mosquitoes suggests that they could transmit various infectious diseases, making it crucial to analyze their interactions. Further research is needed to assess the impact on public health and the potential risk of a new emerging zoonotic disease.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve certain sentences in English. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the publication's content.

FundingThis research was funded by INEVH (ANLIS) and funded partially by Subsidios de Investigación Bianuales (SIB) 2022 EXP-2164/2022 UNNOBA.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Carina Sen for assistance in bioinformatics analysis.