This article presents the results of an exploratory study to identify behavioral styles of professionals performing managing functions in micro and small enterprises. The M.A.R.E. Diagnosis was used to analyze motivational orientation adapted to the context of Brazilian organizations. This quantitative research included 407 managers of small enterprises in the western metropolitan region of São Paulo City (SP). A comparative analysis was conducted of a sample of micro and small business owners and the results of a Brazilian sample collected in previous studies. The results showed that these managers are significantly more focused on Entrepreneurial and Analytical orientations. They are predominantly Producers, Competitors, Achievers, Facilitators, Monitors and Regulators, indicating that the behavioral development of small enterprise managers is associated with their efforts to focus on resources, concerns over improving planning and organization standards in their organizations, and on becoming aware of and implementing much needed innovation.

Na pesquisa aqui relatada buscou-se identificar os estilos comportamentais dos profissionais que exercem funções de comando junto a micro e pequenas empresas. Utilizou-se o diagnóstico M.A.R.E que analisa orientações motivacionais adaptadas para o contexto de organizações brasileiras. Trata-se de uma pesquisa quantitativa envolvendo 407 gestores de microempresas da região metropolitana oeste da cidade de São Paulo (SP). Foi realizada uma análise comparativa da amostra de micro e pequenos empresários com os resultados da amostra brasileira coletada em estudos anteriores. A análise dos resultados apontou que os microempresários estão significativamente mais voltados para as orientações Empreendedora e Analítica, sendo predominantemente pertencentes aos perfis Produtor, Competidor, Realizador, Facilitador, Monitor e Regulador, indicando que o esforço do desenvolvimento comportamental de microempresários acha-se atrelado a um maior foco no mercado e na garantia de recursos, melhoria dos padrões de planejamento e organização de suas empresas, além de se conscientizarem a respeito da imperativa necessidade de inovar.

El artículo presenta los resultados de una investigación exploratoria que tuvo como objetivo identificar los estilos comportamentales de los profesionales que ejercen funciones de comando junto a las micro y pequeñas empresas. Se usó como diagnóstico M.A.R.E, que analiza orientaciones motivacionales adaptadas para el contexto de las organizaciones brasileñas. Se trata de un estudio cuantitativo envolviendo 407 gestores de microempresas de la región metropolitana oeste de la ciudad de São Paulo (SP). Se hizo un análisis comparativo de esta amuestra con los resultados de la amuestra brasileña colectada en estudios anteriores. El análisis de los resultados apuntó que los microempresarios están mucho más inclinados hacia las orientaciones Emprendedoras y Analíticas, y que pertenecen predominantemente a los perfiles Productor, Competidor, Realizador, Facilitador, Monitor y Regulador, indicando que el esfuerzo del desarrollo comportamental de los microempresarios está mucho más centrado en el mercado y en la garantía de recursos, mejoría de los patrones de planeamiento y organización de sus empresas, y también, de tomar conciencia con respecto a la imperativa necesidad de innovar.

In organizational environments, the identification of behavior patterns or styles has aided the recognition of trends in the actions of professionals. This, in turn, provides orientation for training and development and their allocation in work through a guaranteed balance between natural preferences in terms of actions and needs or the requirements of the positions they hold and their activities. Using a reference framework to identify behavior patterns in working situations and built on the reality of Brazilian organizations, the general objective of this article is to identify the behavioral styles of professionals in positions of leadership in micro and small enterprises (MSE), using the western metropolitan region of the city of São Paulo as a research context. The focus of the study is to verify what kind of entrepreneurial behavior they display when working.

This region stands out in the economic context of the city of São Paulo, as its GDP is around 55,000,000 US dollars for a population of almost thirteen million according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, 2016). Furthermore, the 15 municipalities that make up the region implemented a General Law for MSE with a view to obtaining incentives and funding to improve these enterprises. This shows their concern over stimulating entrepreneurship and thus the region may be characterized as a suitable environment for the present study.

Until the mid-nineteen eighties, large organizations were predominant in the world scenario, driven by industrialization and mass production. This trend shifted over time and smaller companies began to gain ground and become increasingly important. Nowadays, their importance cannot be disputed, both in social and economic terms. They also play an important role in competitiveness, the development of new technologies and providing support for big companies (Huang, 2009; Longenecker, Moore, & Petty, 1997).

There are over ten million micro and small entrepreneurs in Brazil. They have steadily come to play a more important role in the economy, and by 2015, they were responsible for 27% of gross domestic product and 52% of the country's registered workforce. It should be emphasized that most MSE are located in the southeast. Indeed, 50% of these companies are located in this region (Brasil, 2015), thereby justifying the sample selected for the purposes of this study.

It is understood that knowledge regarding the possible behavioral profiles of small business executives, both dominant and absent, might shed some light on why the companies they run struggle to survive in the market. This knowledge may also help to guide their development as managers, especially regarding the behavior that they need to put into practice to ensure a more integrated management of their businesses.

Several Brazilian and international studies have found that micro and small enterprises (MSE) are essential for the growth and economic development of any country. In Brazil, MSE are faced with a number of obstacles related to management, survival and regulations. Many of these businesses perish when they attempt to assume a competitive stance.

Among other factors, changing this reality depends on the managers or executives of MSE adopting behavior focused on entrepreneurship, leveraging their competitiveness, profitability, longevity and innovation. This could lead to higher levels of effectiveness, focusing on achievement, being ready for change and adopting a more aggressive stance in the market (Utsch, Rauch, Rothfuß, & Frese, 1999). An entrepreneurial profile has been defined in most consulted theoretical studies on the theme as attitudes and behaviors aimed at facing business-related risks, innovation and competition with other companies in the market.

The present study on the behavioral profiles of small business executives is therefore related not only to entrepreneurship, but also to evaluating the eventual impacts of these profiles on the survival of these companies, which will be the focus of future studies.

Therefore, the contribution to the field intended by the identification of the dominant styles and patterns of behavior of managers building their careers as executives of micro and small businesses is focused on:

- (1)

increasing the possibility for change in these organizations, directing them, through the actions of their managers, to adopt new standards of efficiency, productivity, quality and achieving goals and results;

- (2)

helping the main managers of these organizations to adopt new behaviors and attract and retain human resources with behavioral characteristics compatible with the new challenges;

- (3)

respecting and considering strong and weak points intrinsically associated with probable representative or dominant styles, helping these professionals to adapt better to the work situations in which they are involved or intend to be involved;

- (4)

and (4) identifying behavioral profiles that can help to disseminate attitudes and values to other small business executives from which they can benefit, and aiding the adoption of public policies for the development of entrepreneurship.

The study is warranted because, despite the social and economic importance of small businesses in Brazil, these companies continue to have limited access to technology, and face limitations when it comes to attracting and retaining competent professionals and improving their production methods and management processes (Berne, 2016).

These aspects characterize a growing drive for specialized administration inspired by principles and assumptions that are applied in large enterprises. Micro and small enterprises are under pressure to become more agile, flexible and innovative and especially focused on results in their different lines of business. In this context, it is believed that the performance of the manager or executive of a small or micro enterprise plays a defining role in the transition from the current managerial model to a new and more professional one.

This manager will be responsible for implementing and spearheading the desired change. However, it is assumed that this transition will be more feasible if the behavioral styles of the manager are compatible with the new proposal or the main challenges that have to be faced. Otherwise, instead of leveraging the new model, the manager will become an obstacle to the improvement and professionalization of the enterprise.

Theoretical frameworkThe underlying theoretical foundations for identifying behavioral profiles are based on the belief that different functions require different behavioral patterns and competences. Moreover, different people show these behaviors with different levels of proficiency. There is a growing recognition that different managerial or directing functions have a set of effective and successful behaviors, and that each individual has a unique profile of behavior and personality that influences the balance between professional characteristics and their work requirements and responsibilities (Shelton, Mckenna, & Darling, 2002).

In this section, the main conceptual aspects that support the article and field research are presented and discussed. Basically, concepts are presented of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial behavior, micro and small enterprises, motivational theories based on intrinsic variables, the contribution of the works of Erich Fromm, and the motivational theory of self-determination. It should also be highlighted that there is a description of the main characteristics of the M.A.R.E. motivational orientations (Coda, 2000, 2016) and the identified behavioral profiles, as these aspects represent not only the theoretical basis of the M.A.R.E. Diagnosis, but also provide the foundation of the methodology used in the field research.

Entrepreneurial profileThe economist Joseph Schumpeter popularized entrepreneurship in 1945 as a central concept of his theory of Creative Destruction. To him, an entrepreneur is someone versatile, with technical skills to know how to produce and capitalistic skills to obtain financial resources, organize internal operations and make his company sell. Later, in 1967, with Kenneth E. Knight and, in 1970, with Peter Drucker, the concept incorporated the risk dimension. Thus, an entrepreneurial person needs to take risks in business, showing a predisposition to handle changes, face challenges and generate results. The entrepreneurial posture is also by nature linked to competitiveness and it is worth remembering that many contemporary studies in the field of management are marked by this theme, with several approaches to dealing with competition and competitiveness (Cho & Moon, 2013).

When it comes to small business executives, these aspects related to competitiveness are essential, given the premature death of many of these companies. Furthermore, it should be mentioned that entrepreneurship is the field focused on the development of competences and skills related to a (technical, scientific or entrepreneurial) project. Originating from the French entreprendre, which means to undertake, initiate or begin, an entrepreneur is someone who takes risks and begins something new (Hisrich, Peters, & Shepherd, 2014). The behavior of an entrepreneur encompasses: (a) taking initiative; (b) organizing and reorganizing social and economic mechanisms to transform resources and situation for practical gain; and (c) accepting risk or failure (Shapero, 1975).

Entrepreneurs seize opportunities to create changes, and are not limited to their own personal and intellectual talents to execute an entrepreneurial act. They also mobilize external and internal resources, valuing the interdisciplinary nature of knowledge and experience to achieve their goals. Thus, they value successful experiences, assuming the responsibility for decision making and facing the challenges posed by competitive environments. They act repeatedly, seeking to overcome obstacles (Halikias & Panayotopoulou, 2003). They open new paths, explore and exploit new knowledge, set goals and take the first step, considering that the indicator of their personal and professional success is to be competitive. Psychologically speaking, an entrepreneur is generally a person driven by certain forces such as the need to obtain or achieve something, to experiment or escape from the authority of others (Hisrich et al., 2014).

Another basic characteristic of entrepreneurs is their creative spirit and that of a researcher (Hisrich et al., 2014). They are constantly seeking new solutions, always thinking of people's needs. The essence of a successful entrepreneur lies in seeking new businesses and concern over improving a product (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Studies in the field of entrepreneurship (Filion, 1999; McClelland, 1965; Pino, 1995) have shown that the characteristics of an entrepreneur or the entrepreneurial spirit, of the industry or institution, are more than merely personality traits. Entrepreneurs are also people with certain types of preferential behavior. They have the skill to glimpse and evaluate business opportunities, guaranteeing the resources necessary to put everything into practice. They are individuals motivated to action and concerned with achieving goals.

The findings of more recent studies (Blackburn, Hart, & Wainwright, 2013; Bula, 2012; Mas-Tur, Pinazo, Tur-Porcar, & Sánchez-Masferrer, 2015) corroborate classic studies by bringing to light the propensity for innovation, the exploration of opportunities and capacity for planning as characteristics that stand out among entrepreneurs. In particular, the study by Blackburn et al. (2013) seeks to understand the owner of a small business, the focus of the present study, and that of Mas-Tur et al. (2015) discusses the characteristics of entrepreneurs in the Latin American context, especially their propensity for innovation.

Although the discussion on the conceptual relationship between entrepreneurs and those who start a new business is typical of the 1990s (Filion, 1999), this remains topical as, in both the common sense and in the literature – as proven by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) reports, small business executives are effectively classified as entrepreneurs. In this sense, the work of Shane and Venkataraman (2000, p. 219) may be cited, as the authors claim that “entrepreneurship does not require, but may include, the creation of a new organization”, justifying the consideration of this relationship as an assumption of the present study.

Work motivationFor the purposes of this study, the concept of intrinsic motivation is especially relevant, as the identification of behavioral styles stems from a self-perception of the individual regarding his motivational orientations, revealing impulses to act which are frequently manifested in a person's attitudes. They are intentional and influenced by situations experienced in the social context. This is a variable on the individual level and must be subject to evaluation, its role being to help improve a professional's performance at work (Coda & Cestari, 2008; Coda & Ricco, 2009).

Another point of interest in the context of the present study is the research and work of Deci and Ryan (2000), which resulted in another framework of motivational orientation. This is self-determination theory engages the concept of motivational orientation. The self-determination theory establishes a clear difference between autonomous and controlled forms of motivation. This theory has been applied to predict behaviors in different contexts, such as education, healthcare, companies and sport.

The focus of self-determination theory is concern over identifying inherent tendencies of the growth of people and their innate psychological needs. It is centered on the motivation that exists behind the choices that people make without any interference or influence from external conditions, seeking to evaluate to what extent the behavior of an individual is self-motivated or self-determined.

The assumptions of self-determination theory also consider the way in which cultural and social factors facilitate or compromise the will and initiative of people, complementing the feelings that they have in terms of well-being and the quality of their performances. To Deci and Ryan (2000), whenever individuals have opportunities for autonomy, application of their competences and association, this leads to higher levels of motivation and commitment, including improvements in performance, persistence and creativity.

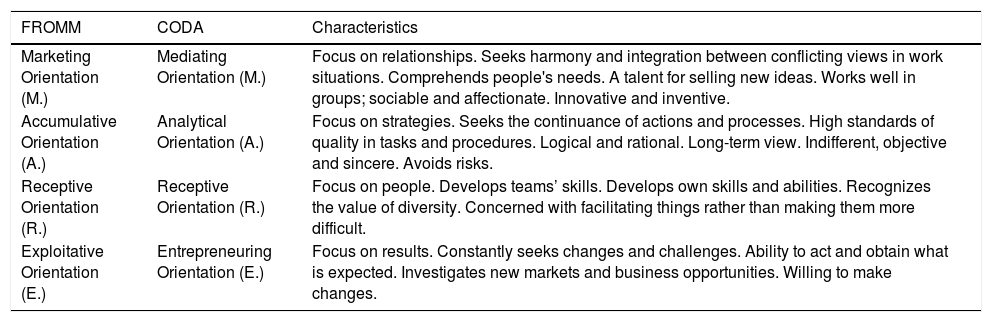

Motivational orientation and the motivational orientations of the M.A.R.E. DiagnosisRelatively stable preferences or tendencies in someone's behavior characterize what is known as “motivational orientation”. This is defined as a behavior pattern that emerges frequently in the attitudes of an individual (Coda, 2016). The M.A.R.E. Diagnosis identifies a cast of 4 (four) motivational orientations in work from a questionnaire created and validated in the context of Brazilian organizations, based on self-perceptions regarding behaviors and favored actions in work, considering the innate personality traits underlying the entire motivational process as a secondary theme. It is based on the four orientations proposed by Fromm (1986), adapted by Coda (2000) for situations and behaviors in the context of working organizations. The motivational orientations are renamed as Mediating, Analytical, Receptive and Entrepreneuring. Table 1 presents a summary of the main characteristics of each of these motivational orientations and a visualization of the parallel established between the classification proposed by Coda (2000) and the one originally developed by Fromm (1986).

Principal characteristics of the M.A.R.E. orientations.

| FROMM | CODA | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing Orientation (M.) | Mediating Orientation (M.) | Focus on relationships. Seeks harmony and integration between conflicting views in work situations. Comprehends people's needs. A talent for selling new ideas. Works well in groups; sociable and affectionate. Innovative and inventive. |

| Accumulative Orientation (A.) | Analytical Orientation (A.) | Focus on strategies. Seeks the continuance of actions and processes. High standards of quality in tasks and procedures. Logical and rational. Long-term view. Indifferent, objective and sincere. Avoids risks. |

| Receptive Orientation (R.) | Receptive Orientation (R.) | Focus on people. Develops teams’ skills. Develops own skills and abilities. Recognizes the value of diversity. Concerned with facilitating things rather than making them more difficult. |

| Exploitative Orientation (E.) | Entrepreneuring Orientation (E.) | Focus on results. Constantly seeks changes and challenges. Ability to act and obtain what is expected. Investigates new markets and business opportunities. Willing to make changes. |

It is important to point out that the approach considers that professionals at work display signs of all these orientations in their activities, with differences occurring in terms of quantity and the order of preference with which each one is used.

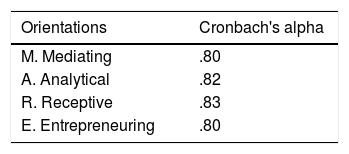

The measurements of reliability of the M.A.R.E. Diagnosis are good for the sample used for validation (Coda, 2000), with a general Alpha coefficient of 0.81. The internal consistency was also good with the respective Cronbach's Alpha coefficients shown in Table 2.

The concept of behavioral profile and the behavioral profiles of the M.A.R.E. DiagnosisThe behavioral profiles identified by the M.A.R.E. Diagnosis represent a professional's valued, intentional and unique dynamic for acting within a given business environment. They result from an interaction of the four motivational orientations considered in the mapping and the type of work situations that are experienced, which can vary from normality to working under pressure.

The mapping of behavioral profiles enables an efficient identification and measurement of a professional's abilities and potential, providing that the techniques used have an effective capacity to provide an accurate forecast of the actions that the collaborator prefers to put into practice in his interactions with colleagues and managers. It is necessary to detect motivations, strong points and other points that need to be developed, as well as reactions to a specific set of circumstances and challenges that arise in the work environment.

The confirmation of these profiles in practice represents an important evolution in the theoretical models on the behavior of managers and leaders, as most existing typologies do not mention reliability indicators and indicators of the validity of the considered constructs (Coda, 2016). Depending on the composition of the behavioral profiles in a given functional area or in the organization as a whole (greater concentration of some or absence of others), investments in self-knowledge, the development of professional abilities (associated with the positions held) and the efforts concentrated on managing change could be better oriented. This could be done either by taking advantage of the strong points of each profile or by allocating or hiring collaborators with behavioral profiles that are different from the dominant ones.

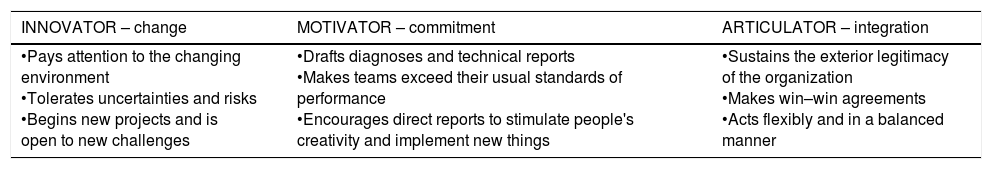

To form a significant database for M.A.R.E. motivational orientations, the diagnostic instrument was applied until a sample of 3217 respondents was obtained, which were collected at the national level. The construction of the behavioral profiles was done by using the multivariate statistical technique known as discriminant analysis. Among other aspects, this technique enables subjects to be classified into groups using a discriminant prediction equation. It also allows a theory to be tested, taking into account whether the subjects of the study have been correctly classified by the theory or analysis model (Coda, 2016). The theory used as a basis for the testing was developed by Cameron, Quinn, Degraff, and Thakor (2014), predicting the existence of 12 behavioral profiles associated with the CVF (Competing Values Framework) Model. There are 3 profiles for each of the 4 managerial models considered in this model (Create, Control, Collaborate and Compete).

Coda (2016) observes that the feasibility of this proposal is considerable, given the compatibility of the four M.A.R.E. Diagnosis orientations and those of the CVF Model. This calculation of the Discriminant Analysis (DA) used the SPSS 21.0 software. First, it was observed that the values of the Wilks’ Lambda test in every case had p-values lower than 0.001, confirming that there is an effective discrimination between the theoretically predicted groups. With the discrimination confirmed, the results of the classifications generated by the DA equations were analyzed. The cross-loadings indicated that 95.2% of the cases are well classified and separated into the 12 categories of the model that was used (CVF), validating the construction of the behavioral profiles (Coda, 2016). Table 3 shows the main behavioral characteristics of the 12 profiles mapped using the M.A.R.E. Diagnosis.

M.A.R.E. behavioral profiles: focus of action and principal characteristics.

| INNOVATOR – change | MOTIVATOR – commitment | ARTICULATOR – integration |

|---|---|---|

| •Pays attention to the changing environment •Tolerates uncertainties and risks •Begins new projects and is open to new challenges | •Drafts diagnoses and technical reports •Makes teams exceed their usual standards of performance •Encourages direct reports to stimulate people's creativity and implement new things | •Sustains the exterior legitimacy of the organization •Makes win–win agreements •Acts flexibly and in a balanced manner |

| COORDINATOR – resources | REGULATOR – continuity | MONITOR – quality |

|---|---|---|

| •Guarantees existing structures and flows •Makes efforts from different areas or teams compatible •Delegates authority and responsibilities | •Guarantees the processes and status of the area or organization in which he operates •Makes programmed changes •Plays safe, avoiding risks | •Specialist in what he does •Masters facts/data/details, is a good analyst •Performs activities carefully |

| MENTOR – development | CONSIDERATOR – cohesion | FACILITATOR – collaboration |

|---|---|---|

| •Dedicated to people's development •Supports claims and demands •Provides advice and feedback to team members | •Seeks to maximize collective efforts during work •Promotes team work, managing interpersonal conflicts •Willing to help others in their work | •Seeks to improve work processes •Provides orientation activities for the team •Makes participative decisions |

| COMPETITOR – profitability | ACHIEVER – execution | PRODUCER – productivity |

|---|---|---|

| •Determine what needs to be done •Monitors the process and stages to obtain what is required •Seeks constant and complex challenges | •Sets goals, defining roles and tasks for team members •Strives to be efficient and effective in his actions, implementing decisions. •Convinces others of his ideas and likes to undertake ventures | •Persists in the drive for goals and results •Constantly accumulates achievements •Creates strategies and respective plans of action |

From the theoretical considerations presented here, the following research questions were defined for the fieldwork:

RQ1 – Are there more predominant or more absent motivational orientations among the small business executives in the region in question?

RQ2 – Are there dominant behavioral profiles in the sample in question?

RQ3 – Do the small business executives in the region under study display characteristics of the entrepreneurial profile as described in the literature?

In the present study these questions are intended to help bridge the theoretical gap in studies on the profile of entrepreneurs, as they stress on researching behaviors and favored actions, leaving aside personality traits, attitudes and personal characteristics of the entrepreneur, in accordance with the focus of the M.A.R.E. approach (Coda, 2016).

Methodological proceduresThe fieldwork for mapping the behavioral profiles was conducted through a non-probabilistic electronic survey. Small and micro business executives from the western and southwestern metropolitan region of São Paulo were invited to participate in the study. Several criteria can be used to define this type of business. Some criteria rely on turnover (BNDES, 2011; Brasil, 2011), some on the number of employees (IBGE, 2001; SEBRAE, 2013) and others on particular characteristics (Filion, 1990). For the purposes of this study, the classification proposed by Supplementary Law 23/2006 (Brasil, 2011) was used. According to this law, micro enterprises have a gross annual revenue of US$ 120,000 (one hundred and twenty thousand dollars) or less, while small businesses have one of up to US$ 1,200,000 (one million, two hundred thousand dollars). The criterion of the Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (SEBRAE, 2013) was also considered. It determines that micro enterprises have up to 19 employees in industry and 9 in commerce and services, while small businesses employ up to 99 people in industry and 49 in commerce and services.

The SEBRAE-Osasco database was used, which has 28,000 registrations. The authors were granted access to this database. The members were given an individual password for access to the M.A.R.E. Diagnosis on a website specially designed for this purpose. A target sample of n=400 respondents was set, as this number is considered adequate to represent sample surveys of large and unknown populations of interest (Hair, Babin, Money, & Samouel, 2005). The individuals who agreed to take part in the study were given a week to complete the questionnaire and the data collection continued until the target sample was achieved, closing when the number of respondents reached n=407.

In the present study, a comparative analysis of the sample of micro and small entrepreneurs (MSE) was conducted, with the results of the Brazilian sample collected in previous studies (Coda, 2016). This was done not only to research the proposed questions (RQ1, RQ2 and RQ3), but also to assess whether there are differences between the predominance (i.e., proportion) and ranking (i.e., relative position) of M.A.R.E. motivational orientations and the 12 behavioral profiles that stem from them, considering the sample of MSE and the Brazilian sample.

The independent variables of the study (M.A.R.E. behavioral profiles) can only be obtained by applying the respective diagnosis. A recommendation for addressing this potential methodological bias is to investigate whether the study of these variables can also be obtained in other contexts (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). This is the case of the present study. The authors also suggest that one way to address this bias is to pay attention to the research instrument. The M.A.R.E. questionnaire has reliability indicators, as shown in Table 2.

To compare the predominance (i.e., proportion) between the two samples, for both the motivational orientations and the 12 behavioral profiles, the chi-square test of independence was used, followed by comparisons of paired proportions with Bonferroni adjustments (Agresti, 2010). The chi-square test of independence is used when the intention is to compare nominal qualitative variables, and it serves to gauge whether the proportions at the levels of a variable change in accordance with another (or other) variables. In other words, if the proportion of at least one level (e.g., Motivational orientation) of a nominal qualitative variable (e.g., M.A.R.E. Diagnosis) varies in accordance with another variable (e.g., MSE sample vs. Brazilian sample), the chi-square test will be significant.

However, it is necessary to use multiple comparisons of proportions to evaluate which profile or orientation differs between one sample and another. In other words, all the levels of a nominal qualitative variable are tested between samples (e.g., MSE sample vs. Brazilian sample) to conclude, statistically, which levels have larger, smaller or equal proportions.

To draw a comparison between the ranking (i.e., relative position) of the motivational orientations and the 12 behavioral profiles, the non-parametric measurements of Kendall's tau-b ordinal correlation, Spearman's rho and Goodman and Kruskal's gamma were used (Agresti, 2010). These measurements gauge the degree to which the order of ordinal responses in two different variables is equivalent or not. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 software.

ResultsAnalysis of the sample of small business executivesThe composition of the sample obtained was balanced in terms of gender (51% male and 49% female). Regarding schooling, most had completed higher education (46%), 26% had a high school diploma and 20% had completed post-graduation courses (specialization, Master's or Doctorate Degree). The average number of employees of the companies in which the respondents worked was 15, and, on average, the companies had been operational for 10 years.

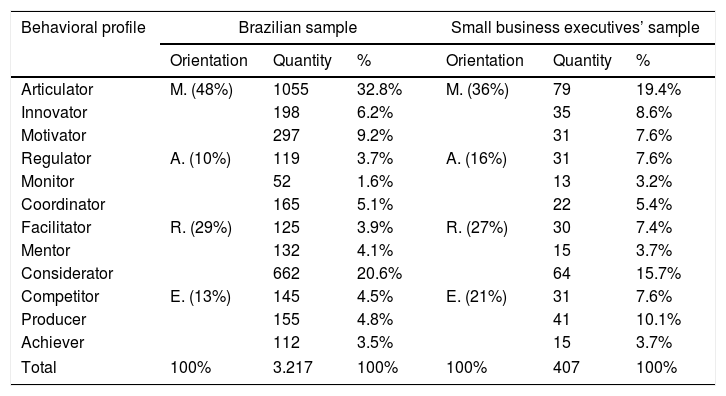

The results indicate that the predominant motivational orientation in the sample of micro entrepreneurs is Mediating (M), with 36%, followed by Receptive (R) with 27%, Entrepreneuring (E), with 21% and, finally, the most absent, Analytical (A), with 16%. The predominant behavioral profiles are Articulator (19.4%), Considerator (15.7%) and Producer (10.1%), with the absent ones being Monitor (3.2%), Achiever and Mentor (3.7% each). The results of the M.A.R.E. Diagnosis and its 12 behavioral profiles for the samples considered in the present study (sample of small business executives and Brazilian sample) (Coda, 2016) are shown in Table 4.

Distribution of M.A.R.E. behavioral profiles of micro and small business – western and southwestern metropolitan region of São Paulo.

| Behavioral profile | Brazilian sample | Small business executives’ sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation | Quantity | % | Orientation | Quantity | % | |

| Articulator | M. (48%) | 1055 | 32.8% | M. (36%) | 79 | 19.4% |

| Innovator | 198 | 6.2% | 35 | 8.6% | ||

| Motivator | 297 | 9.2% | 31 | 7.6% | ||

| Regulator | A. (10%) | 119 | 3.7% | A. (16%) | 31 | 7.6% |

| Monitor | 52 | 1.6% | 13 | 3.2% | ||

| Coordinator | 165 | 5.1% | 22 | 5.4% | ||

| Facilitator | R. (29%) | 125 | 3.9% | R. (27%) | 30 | 7.4% |

| Mentor | 132 | 4.1% | 15 | 3.7% | ||

| Considerator | 662 | 20.6% | 64 | 15.7% | ||

| Competitor | E. (13%) | 145 | 4.5% | E. (21%) | 31 | 7.6% |

| Producer | 155 | 4.8% | 41 | 10.1% | ||

| Achiever | 112 | 3.5% | 15 | 3.7% | ||

| Total | 100% | 3.217 | 100% | 100% | 407 | 100% |

A chi-squared test was performed using cross tabulation between the qualitative variables and M.A.R.E. orientations for the national sample and sample of small business executives. A chi-square statistic of 42.69 (gl=3; p<0.01%) was obtained, indicating that there are statistically significant differences between the samples.

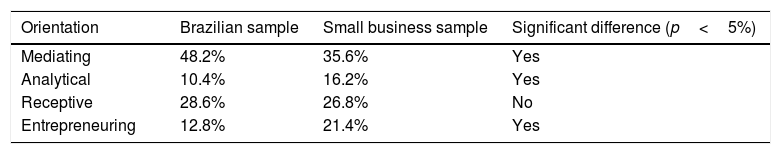

To evaluate which orientations were different between the samples, multiple paired comparisons were drawn between them with Bonferroni correction. The results indicated (Table 5) that the proportions between the two samples were significantly different for Mediating orientation (pNational=48.2% vs. pSmall-business-executives=35.6%, p<5%), with this being more prevalent in the national sample; Analytical (pNational=10.4% vs. pSmall-executives=16.2%, p<5%), with this being more prevalent in the sample of small business executives; Entrepreneuring, prevalent in the small business executives sample (pNational=12.8% vs. pSmall-executives=21.4%, p<5%), with this being more prevalent in the small business executives sample. There were no statistically significant differences, at a level of 5%, between the two samples in Receptive orientation (pNational=28.6% vs. pSmall-executives=26.8%, p>50%).

Comparison of the proportions of motivational orientations in the national and small business executives samples.

| Orientation | Brazilian sample | Small business sample | Significant difference (p<5%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating | 48.2% | 35.6% | Yes |

| Analytical | 10.4% | 16.2% | Yes |

| Receptive | 28.6% | 26.8% | No |

| Entrepreneuring | 12.8% | 21.4% | Yes |

To gauge whether there are differences in the rankings, based on their prevalence, the non-parametric ordinal correlation measurements were calculated for the two samples. As expected, Kendall's tau-b, Spearman's rho and Goodman and Kruskal's gamma were 1, indicating that the rankings by prevalence of M.A.R.E. orientation are exactly the same in the Brazilian and small business executives samples.

Together, these results show that the national tendency of a greater prevalence of ranking for Mediating, followed by Receptive, Entrepreneuring and Analytical, is repeated in the small business executives’ sample. However, a close analysis of the proportions shows that the small business executives sample has a significantly higher proportion of individuals with Entrepreneuring and Analytical orientations than the national sample, although the latter is less prevalent. The Mediating orientation in turn is more frequently observed in the national sample. The only orientation that does not differ from one sample to another is Receptive.

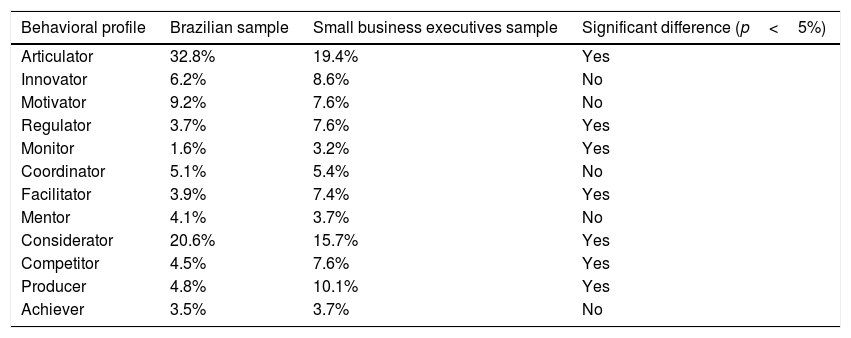

For the Behavioral Profiles, a chi-squared test was conducted using cross tabulation for the qualitative variables and Behavioral Profiles for the national sample and the small business executives. A chi-square statistic of 83.9 (gl=11; p<0.01%) was obtained, indicating that there are statistically significant differences between the samples. As in the analysis of M.A.R.E. Orientations, multiple paired comparisons were made between the samples with Bonferroni correction to gauge the differences in the proportions.

The results indicated that the proportions for the two samples were significantly different for the profiles of Articulator (pNational=32.8% vs. pSmall-executives=19.4%, p<5%), Regulator (pNational=3.7% vs. pSmall-executives=7.6%, p<5%), Monitor (pNational=1.6% vs. pSmall-executives=3.2%, p<5%), Facilitator (pNational=3.9% vs. pSmall-executives=7.4%, p<5%), Considerator (pNational=20.6% vs. pSmall-executives=15.7%, p<5%), Competitor (pNational=4.5% vs. pSmall-executives=7.6%, p<5%) and Producer (pNational=4.8% vs. pSmall-executives=10.1%, p<5%). There were no statistically significant differences, at a level of 5%, between the two samples for Innovator (pNational=6.2% vs. pSmall-executives=8.6%, p<10%), Motivator (pNational=9.2% vs. pSmall-executives=7.6%, p<10%), Coordinator (pNational=5.1% vs. pSmall-executives=5.4%, p<10%), Mentor (pNational=4.1% vs. pSmall-executives=3.7%, p<10%) and Achiever (pNational=3.5% vs. pSmall-executives=3.7%, p>10%).

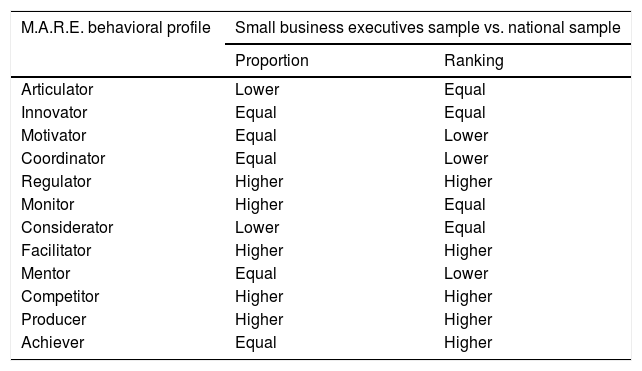

The result of the 12 paired comparison tests is shown in Table 6.

Comparison of the proportions of behavioral profiles of national and small business samples.

| Behavioral profile | Brazilian sample | Small business executives sample | Significant difference (p<5%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Articulator | 32.8% | 19.4% | Yes |

| Innovator | 6.2% | 8.6% | No |

| Motivator | 9.2% | 7.6% | No |

| Regulator | 3.7% | 7.6% | Yes |

| Monitor | 1.6% | 3.2% | Yes |

| Coordinator | 5.1% | 5.4% | No |

| Facilitator | 3.9% | 7.4% | Yes |

| Mentor | 4.1% | 3.7% | No |

| Considerator | 20.6% | 15.7% | Yes |

| Competitor | 4.5% | 7.6% | Yes |

| Producer | 4.8% | 10.1% | Yes |

| Achiever | 3.5% | 3.7% | No |

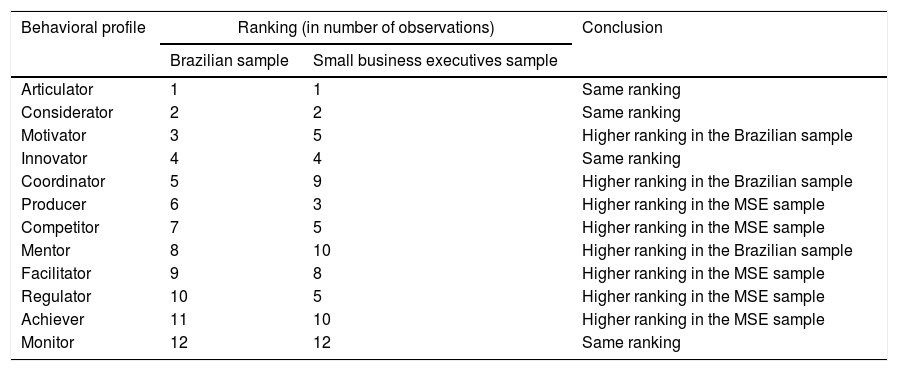

To gauge whether there are differences in the rankings, based on prevalence, non-parametric ordinal correlation measurements were calculated to compare the two samples. Kendall's tau-b was 0.657 (p<0.4%), Spearman's rho was 0.794 (p<0.2%) and Goodman and Kruskal's gamma was 0.677 (p<0.01%). These results show that despite a significant tendency for the rankings to remain the same, some profiles are in different positions in each of the samples.

The profiles of Articulator and Considerator, for instance, were ranked 1 and 2, respectively, in both samples. However, the Coordinator profile, for example, was ranked 5 in the national sample and 9 in the small business executive sample. Each of these profiles is shown in Table 7 based on their rankings.

Comparison of the rankings of the national sample and the sample of small business executives.

| Behavioral profile | Ranking (in number of observations) | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazilian sample | Small business executives sample | ||

| Articulator | 1 | 1 | Same ranking |

| Considerator | 2 | 2 | Same ranking |

| Motivator | 3 | 5 | Higher ranking in the Brazilian sample |

| Innovator | 4 | 4 | Same ranking |

| Coordinator | 5 | 9 | Higher ranking in the Brazilian sample |

| Producer | 6 | 3 | Higher ranking in the MSE sample |

| Competitor | 7 | 5 | Higher ranking in the MSE sample |

| Mentor | 8 | 10 | Higher ranking in the Brazilian sample |

| Facilitator | 9 | 8 | Higher ranking in the MSE sample |

| Regulator | 10 | 5 | Higher ranking in the MSE sample |

| Achiever | 11 | 10 | Higher ranking in the MSE sample |

| Monitor | 12 | 12 | Same ranking |

The results of the analyses of the M.A.R.E. orientations and the 12 profiles suggest that, despite the tendency of the Brazilian sample being reflected in the small business executives sample, there are a number of specific differences that are not found when particular comparisons are made. In general, the results show that among the small business executives there is a higher proportion of individuals with Analytical and Entrepreneuring orientations as well as a higher proportion of individuals with the profiles of Regulator, Monitor, Facilitator, Competitor and Producer.

The apparent differences between the comparison of proportions and comparison of rankings should be considered. The Achiever profile, for instance, does not show a statistically different proportion between one sample and the other, but has a higher ranking in the small business executives’ sample. This occurs because a proportion is affected by the magnitude of the other proportions. The Articulator profile corresponds to 32.8% in the Brazilian sample and 19.4% in the small business executives’ sample, with this profile ranking 1 in both samples. The Monitor profile has 1.6% in the Brazilian sample and 3.2% in the small business executives sample (double), although this profile ranks 12 in both samples. As the proportion of Articulators is 13.4% higher in the Brazilian sample, several other proportions are lower in comparison with the small business executives’ sample. When the objective is to gauge whether a profile occurs more frequently in one sample than in the other, it is recommended that the conclusion be oriented by the comparison between proportions.

If the intention is to gauge whether the importance of one profile within a sample is the same in relation to the other, the option of comparing the rankings is recommended. It should also be considered that some profiles had equal rankings in the small business executives sample (Motivator, Competitor and Regulator in 5th place; Mentor and Achiever in 10th place), and it is necessary to exercise caution when making direct comparisons between the results in proportion and ranking. A number of differences were also found in the ranking, where the profiles of Producer, Competitor, Facilitator, Regulator and Achiever had higher rankings (in prevalence) in the small business executives sample than in the Brazilian sample.

Discussion of the resultsAccording to the data analysis, some M.A.R.E. behavioral profiles stood out in the small business executives sample in comparison with the national sample (Table 8), as they meet at least one of the criteria used for classification as Higher: Regulator, Monitor, Facilitator, Competitor, Producer and Achiever. The other profiles in the small business executives sample not shown in Table 8 meet the analysis criteria for classification as Lower or Equal to the national sample. Therefore, they are not characteristics of the research sample (small business executives).

Comparison of behavioral profile between samples.

| M.A.R.E. behavioral profile | Small business executives sample vs. national sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion | Ranking | |

| Articulator | Lower | Equal |

| Innovator | Equal | Equal |

| Motivator | Equal | Lower |

| Coordinator | Equal | Lower |

| Regulator | Higher | Higher |

| Monitor | Higher | Equal |

| Considerator | Lower | Equal |

| Facilitator | Higher | Higher |

| Mentor | Equal | Lower |

| Competitor | Higher | Higher |

| Producer | Higher | Higher |

| Achiever | Equal | Higher |

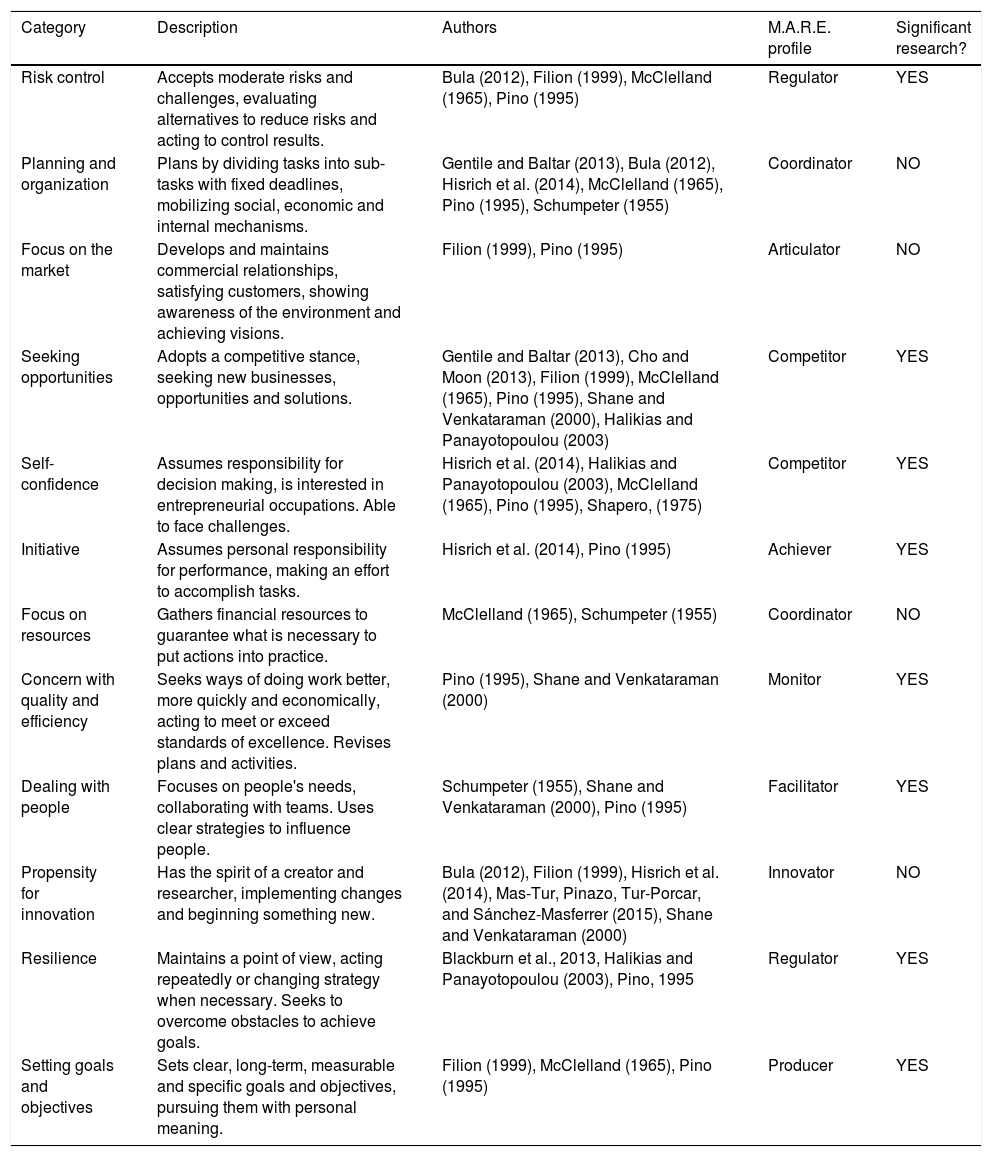

The profiles shown and their respective behavioral characteristics (see Table 3) served as a basis for a comparison with the characteristics listed in the consulted literature as representative of the entrepreneur profile. This comparison is shown in Table 9.

Summary of the entrepreneurial characteristics listed in the consulted literature.

| Category | Description | Authors | M.A.R.E. profile | Significant research? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk control | Accepts moderate risks and challenges, evaluating alternatives to reduce risks and acting to control results. | Bula (2012), Filion (1999), McClelland (1965), Pino (1995) | Regulator | YES |

| Planning and organization | Plans by dividing tasks into sub-tasks with fixed deadlines, mobilizing social, economic and internal mechanisms. | Gentile and Baltar (2013), Bula (2012), Hisrich et al. (2014), McClelland (1965), Pino (1995), Schumpeter (1955) | Coordinator | NO |

| Focus on the market | Develops and maintains commercial relationships, satisfying customers, showing awareness of the environment and achieving visions. | Filion (1999), Pino (1995) | Articulator | NO |

| Seeking opportunities | Adopts a competitive stance, seeking new businesses, opportunities and solutions. | Gentile and Baltar (2013), Cho and Moon (2013), Filion (1999), McClelland (1965), Pino (1995), Shane and Venkataraman (2000), Halikias and Panayotopoulou (2003) | Competitor | YES |

| Self-confidence | Assumes responsibility for decision making, is interested in entrepreneurial occupations. Able to face challenges. | Hisrich et al. (2014), Halikias and Panayotopoulou (2003), McClelland (1965), Pino (1995), Shapero, (1975) | Competitor | YES |

| Initiative | Assumes personal responsibility for performance, making an effort to accomplish tasks. | Hisrich et al. (2014), Pino (1995) | Achiever | YES |

| Focus on resources | Gathers financial resources to guarantee what is necessary to put actions into practice. | McClelland (1965), Schumpeter (1955) | Coordinator | NO |

| Concern with quality and efficiency | Seeks ways of doing work better, more quickly and economically, acting to meet or exceed standards of excellence. Revises plans and activities. | Pino (1995), Shane and Venkataraman (2000) | Monitor | YES |

| Dealing with people | Focuses on people's needs, collaborating with teams. Uses clear strategies to influence people. | Schumpeter (1955), Shane and Venkataraman (2000), Pino (1995) | Facilitator | YES |

| Propensity for innovation | Has the spirit of a creator and researcher, implementing changes and beginning something new. | Bula (2012), Filion (1999), Hisrich et al. (2014), Mas-Tur, Pinazo, Tur-Porcar, and Sánchez-Masferrer (2015), Shane and Venkataraman (2000) | Innovator | NO |

| Resilience | Maintains a point of view, acting repeatedly or changing strategy when necessary. Seeks to overcome obstacles to achieve goals. | Blackburn et al., 2013, Halikias and Panayotopoulou (2003), Pino, 1995 | Regulator | YES |

| Setting goals and objectives | Sets clear, long-term, measurable and specific goals and objectives, pursuing them with personal meaning. | Filion (1999), McClelland (1965), Pino (1995) | Producer | YES |

Although this list of characteristics is not extensive, it does provide a framework of reference to help explain why some individuals become entrepreneurs while others do not. It also shows the behaviors and attitudes that underline the will to put the entrepreneurial spirit to work, helping to answer the third research question in the present study.

It should be noted that the results of these above mentioned studies are at times conflicting: some stress that entrepreneurs must put risk management into practice while others stress a demand an attitude of unconditional risks acceptance. There are also behaviors that can be viewed as opposites, meaning that at the end of the day entrepreneurs are almost required to have a dual personality. For example, one moment they are expected to focus on innovation, while in other situations they are expected to focus on internal efficiency.

However, the present study reveals that in practice, although some behaviors of small business executives are favored, as they represent natural tendencies of action, others could be targets for development to improve the skills and efficiency of these executives to meet the demands of new and different situations or new environments that they will face. The behaviors in these cases are focused on the market, with adequate planning and organization of activities, resource management and especially the management and planning of innovation. Thus, small business executives have to develop characteristics and behaviors that match the profiles of Articulator and Innovator, which were not significant in the sample in question, which highlight innovation as a frequent variable in contemporary approaches to entrepreneurship and not merely related to the opening of new small businesses.

Table 9 shows that the M.A.R.E. behavioral processes adhere to 75% of the categories of the entrepreneur profile, confirming the general question of the present article regarding to what extent small business executives effectively have entrepreneurial characteristics. It is interesting to note that the comparison with the categories found in the literature reveals aspects not related only to the profiles that stem from the motivational orientation of Entrepreneuring evaluated by the M.A.R.E. Diagnosis, but also to the profiles linked to the Analytical and Mediating orientations.

The results obtained in the study are compatible with the work of Moroku (2013), viewing Entrepreneur Orientation as an antecedent for explaining entrepreneurial behavior, i.e., the behavior of someone who wishes to start or own his or her business. However, this orientation is not a statistically significant factor when it comes to explaining a successful performance by the executives of a business.

Sadler-Smith, Hampson, Chaston, and Badger (2003) show that the entrepreneurial profile is correlated to the management of culture and the management of vision, while performance management is correlated to a non-entrepreneurial profile. Regarding the M.A.R.E. behavioral profiles, the correlated profiles are Articulator, which was not significant in the study, Achiever and Competitor, which were significant. The study also indicates that the entrepreneurial profile in SME is positively associated with the probability of this type of business enjoying high levels of growth.

A study conducted in the United Kingdom (Blackburn et al., 2013), found that small business executives see themselves as traditional business executives, seizing opportunities whenever they can, basing their decisions on known facts and keeping a low profile. Most of those involved in the study were conservative in the use of new technologies, preferring to wait for tried and tested systems. The results confirm the consolidated views that small business executives desire independence and are reluctant to plan ahead, and that a considerable percentage of them see themselves as tireless and easily bored, characteristic traits of entrepreneurship.

In a bibliometric study conducted in Sweden (Andersson & Tell, 2009), articles published in the last 25 years were examined focusing on identifying how the leading manager influences the growth of micro enterprises. Three key factors that influence this growth were discovered: (1) personal traits and characteristics of the manager; (2) the manager's intentions (motivations) and (3) managerial roles or behaviors. The study noted that results found in published literature are contradictory, painting a paradoxical portrait regarding the impact of the manager on the performance of small and micro enterprises. The results of the field research in this study also reveal conflicting aspects, such as managers adopting not only a competitive stance but a regulative one as well. This shows the need for future studies to clarify these points.

Conclusions, limitations and implications for future studiesWhen this study began, a theoretical gap was found regarding the profile of the Brazilian managers of micro and small businesses, especially concerning their most and least prominent characteristics. The literature states that not all business executives are entrepreneurs, but that they are either one or the other. The possibility for comparison with the national profile presented in the M.A.R.E. Diagnosis emphasized the importance of the three research questions in the present article.

The predominant motivational orientations were Entrepreneuring and Analytical. Mediating was the least prominent. In the case of Entrepreneuring orientation, this result was expected. However, in the case of Analytical orientation, its greater presence helps to explain characteristics of the entrepreneurial profile that are more closely related to risk control and the continuation of the business.

Regarding behavioral profiles, the results showed that the dominant ones were Competitor, Producer, Achiever, Facilitator, Monitor and Regulator. The non-predominance of the Innovator profile is interesting, although the literature highlights innovation as the differentiator between business executives and entrepreneur. This result is in keeping with the study by Berne (2016), which sought to map the degree of innovation in micro and small businesses, concluding that innovation is not a normal practice in this type of organization. How is it possible to innovate if the executive does not have the profile of an Innovator?

A comparison with the theory on characteristics of the entrepreneurial profile led to the conclusion that of the 12 categories identified, 8 directly correspond with one of the 6 predominant behavioral profiles in the sample. Thus, it may be concluded that approximately 70% of the entrepreneurial characteristics are present in the profiles of the small business executives in the western metropolitan region of the city of São Paulo.

As is the case in all forms of scientific research, limitations were perceived in this study. The first has to do with the selection of the region, which was chosen for easy access and cannot be generalized for the whole of São Paulo State, despite the expressiveness of the sample number. The second limitation is that the sample was not probabilistic as participation was voluntary.

Future studies should be conducted to establish a correlation between behaviors and profiles of small business executives and growth or performance of the company that they run, as has been done in a number of international studies on entrepreneurial profiles. This is a trend, as several of the studies discussed have shown that individual characteristics and traits of an entrepreneur can affect micro and small business growth. Future studies should be conducted in other states and other metropolitan regions of São Paulo State in order to draw comparisons and obtain confirmation of the results found in the present study.

Another possibility for research would be to explore other variables that might stimulate entrepreneurial behavior among Brazilian small business executives to help form and consolidate a strong entrepreneurial culture in this business context. An example would be to research possible links or overlaps between entrepreneurial and market orientations.

The study indicates that the strength of the behavioral development of small business executives relies on a greater focus on the market and guaranteeing resources, improving planning and organization of their companies and raising awareness of the need to innovate.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.