Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (EBCR) programmes are strongly recommended to enhance exercise capacity and quality of life in heart failure (HF). However, their effects on dyspnoea have not been systematically reviewed, possibly due to the knowledge gap in the assessment of dyspnoea. The aim of this study was to recognise the dyspnoea tool used in HF for the EBCR trial, assess the effects of EBCR on dyspnoea and identify which patient characteristics and FITT parameters (Frequency, Intensity, Time and Type) are associated with better outcomes. A review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials following the PRISMA guideline were performed, including fifteen studies (n=766 participants). Up to 8 dyspnoea measurement instruments were identified in the studies. EBCR showed a moderate effect size on dyspnoea (d=0.69, 95% CI 0.54–0.84). Larger effects were seen in patients<65 years (d=0.77, 95% CI 0.54–0.99) and in non-hospitalised patients (d=0.735, 95% CI 0.550–0.921). Greater effects were observed for low-intensity (d=0.79, 95% CI 0.44–1.15) and multimodal programmes (d=1.12, 95% CI 0.47–1.77). Programmes with three sessions per week and ≥12 weeks were the most common. Findings were limited due to the varying dyspnoea scales, highlighting the need for standardised assessment in HF.

Los programas de rehabilitación cardíaca basada en ejercicio (RC-BE) cuentan con una sólida recomendación para mejorar la capacidad funcional y la calidad de vida en pacientes con insuficiencia cardíaca. Sin embargo, sus efectos sobre la disnea no han sido revisados de forma sistemática posiblemente debido a la brecha de conocimiento sobre medidas de disnea. El objetivo de este estudio fue reconocer los instrumentos de evaluación de la disnea en insuficiencia cardíaca durante los programas de RC-BE, evaluar los efectos de la RC-BE sobre la disnea e identificar qué características del paciente y parámetros FITT (Frecuencia, Intensidad, Tiempo y Tipo) están asociados con mejores resultados. Se realizó una revisión y metaanálisis de ensayos controlados aleatorizados siguiendo la guía PRISMA, que incluyó 15 estudios (n=766 participantes). Hasta 8 instrumentos de evaluación de la disnea fueron identificados. La RC-BE mostró un tamaño del efecto moderado sobre la disnea (d=0,69, IC 95% 0,54 a 0,84). Se observaron efectos mayores en pacientes<65 años (d=0,77, IC 95% 0,54 a 0,99) y en pacientes no hospitalizados (d=0,735, IC 95% 0,550 a 0,921). Los efectos fueron mayores en programas de baja intensidad (d=0,79, IC 95% 0,44 a 1,15) y multimodales (d=1,12, IC 95% 0,47 a 1,77). Los programas con 3 sesiones por semana y una duración≥12 semanas fueron los más comunes. Los hallazgos estuvieron limitados por la variabilidad de las escalas de disnea, lo que destaca la necesidad de una evaluación estandarizada en la insuficiencia cardíaca.

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes of dyspnoea. It is associated with a high disease burden and is a risk factor for mortality in this population group. In HF patients, dyspnoea is a common and often disabling symptom, affecting up to 80% of HF patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and up to 60% of HF patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).1

The pathophysiology of dyspnoea in HF is complex and involves multiple mechanisms, including pulmonary congestion, respiratory muscle dysfunction, and impaired peripheral oxygen utilisation. The treatment of dyspnoea in the HF population includes addressing its underlying cause. Treatments may include pharmacological interventions, such as diuretics, beta-blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, as well as non-pharmacological interventions, such as oxygen therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation.2

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (EBCR) programmes, which include exercise therapy intervention, are strongly recommended in the current guidelines to improve exercise capacity, quality of life (QoL), and reduce HF hospitalisation.3 However, the effectiveness of EBCR programmes on dyspnoea has not been analysed in the subsequent systematic review and meta-analysis.4–6 Indeed, the knowledge gap in the assessment of dyspnoea could be a barrier for clinical research to explore this effect.7,8

Therefore, the present study aims to (a) recognise the dyspnoea tools used in EBCR trials; (b) analyse the effectiveness of EBCR on dyspnoea in patients with HF, (c) identify which patient characteristics and FITT parameters (Frequency, Intensity, Time and Type) are associated with better outcomes of EBCR for dyspnoea in HF.

Materials and methodsThe PRISMA statement was followed for the systematic review and meta-analysis. Supplementary Material 1 contains the completed PRIMA 2020 checklist.9

Search strategyUsing the Mesh terms ‘Heart Failure’, ‘Dyspnea’, and ‘Exercise Therapy’, two independent reviewers (CG-C and CR-J) conducted a systematic search from inception to February 2025. Optimised search strategies were implemented in the following electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and Web of Science. The Zotero 6 for Windows reference management software was used to remove duplicates and export references. The search strategy for each electronic database and the hierarchy of search terms are shown in Supplementary Material 2.

Eligibility criteriaThe systematic review and meta-analysis followed the PICOS framework10 to determine which studies would be included.

Inclusion criteria- (1)

Patient (P): Studies with a target population of patients with HF.

- (2)

Intervention (I): Studies including exercise therapy in their EBCR programmes.

- (3)

Comparison (C): Studies that present, as a control group, conventional treatments, usual care, or education.

- (4)

Outcomes (O): Studies measuring dyspnoea.7,8,11

- (5)

Studies (S): Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

- (1)

Studies in which HF patients were mixed with other pathologies (e.g., Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)).

- (2)

Studies in which dyspnoea was not measured or non-specified.

Two reviewers, CG-C and CR-J, independently evaluated the titles and abstracts of potentially relevant records and excluded non-original papers. The same reviewers assessed articles that met all eligibility criteria, following a short checklist (Supplementary Material 3) to select suitable trials. If there were any discrepancies, articles were still included.

Data extractionCG-C and CR-J extracted relevant data from each study, including study details (first author and year of publication), dyspnoea outcomes, patient characteristics and the description of EBCR programmes.

EBCR programmes were described based on FITT exercise parameters. Exercise intensities were stratified according to the intensity monitoring or prescribing parameters used in each study, considering12–15:

- •

Low intensity: <40% heart rate reserve (HRR) or % peak oxygen consumption (peakVO2), <64% peak heart rate (peakHR), or <12 rating of perceived exertion (RPE) on the 6–20 scale for aerobic, and <50% of one-repetition maximum and the external load (1-RM) or maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP) for strength exercise.

- •

Moderate intensity: 40–59% HRR or %peakVO2, 64–76% peakHR, or 12–13 RPE on the 6–20 scale for aerobic and 50–70% 1-RM or MIP for strength exercise.

- •

Vigorous intensity: 60–84% HRR or %peakVO2, 77–93% peakHR, or 14–16 RPE on the 6–20 scale for aerobic, and >70% 1-RM or MIP for strength exercise.

To detail the type of exercise, EBCR programmes were classified into:

- •

Unimodal EBCR programmes, which include one type of exercise, such as aerobic training (AT) or inspiratory muscle training (IMT).

- •

Multimodal EBCR programmes, which involve two or more types of exercises, for example, the combination of strength training and AT.

When the data necessary for this study were not originally reported, the authors were contacted by email in an attempt to obtain missing information.

Quality assessmentCG-C and CR-J used the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale to assess the risk of bias in the RCTs included in the study. The PEDro scale has been considered a valid measure for evaluating the methodological quality of clinical trials.16

Data synthesis and analysisStatistical analyses were conducted utilising Jamovi Graphical User Interface version 2.4.11.17 Between-group effect sizes were calculated by comparing the respective groups’ post-intervention means and standard deviations. The effect size of the treatment was interpreted using Cohen's d, d<0.2 being an absence of effect, 0.2≤d<0.5 showing a small effect, 0.5≤d<0.8 showing a moderate effect, and d≥0.8 showing a large effect.18 Effect sizes were weighted using the variances of the variables.19 The overall effect was tested with the Z statistic, with a significance level set at p<0.05.18 In cases where multiple dyspnoea outcomes were reported, one of the dyspnoea scales was randomly selected from single randomisation to avoid double-counting in meta-analysis.

Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using the χ2 test. Depending on the presence or absence of heterogeneity, we chose to use the random or fixed effects model, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the safety analysis.20 Sensitivity analyses were performed, and publication bias was assessed using a visual inspection of a funnel plot. Additionally, Begg's adjusted rank correlation test was used to evaluate publication bias quantitatively.20,21

Subgroup analyses were performed to investigate the influence of significant factors on EBCR according to patient characteristics, such a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), age, and hospitalisation status, and the parameters of the FITT formula.22

ResultsStudy selectionInitially, 1740 citations were found in electronic databases, from which 1571 were reviewed. After screening titles and abstracts, 26 full articles were selected for assessment, of which 11 were subsequently excluded for various reasons. Finally, 15 articles were included in this review. Fig. 1 shows the number of studies retrieved from each database and the number of studies excluded in each selection phase.

Instruments for measuring dyspnoeaUp to 8 dyspnoea measurement instruments were identified in the studies. The modified Borg dyspnoea scale was not included in the meta-analysis due to data collection at different time points. The most repeated instruments in the meta-analysis were the modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) scale, the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire (MLHFQ), and the dyspnoea index (DI). Most studies reported the overall score for MLHFQ and for the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ). Four other measures used to assess dyspnoea are listed in Table 1.

Description of included studies.

| Studies | Patient characteristics | EBCR programme | Dyspnoea scales | ES (Cohen's d) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n IG/CG | Mean age (SD) | Mean LVEF % (SD) | n NYHAII/III/IV | F | I | T | T (type) | |||

| Gary et al.23 | 16/16 | 67 (11) | 57 (9) | 13/19 | 3 | 40–60% HRR | 12 | AT | MLHFQ | 0.25 |

| Beniaminovitz et al.31 | 17/8 | 50 (16.5) | 18 (4.12) | NA | 3 | 50% peakVO2 | 12 | AT | TDI | 1.105 |

| Corvera-Tindel et al.27 | 37/42 | 63.8 (10.1) | 29.1 (8.5) | 64/25 | 5 | 40–65% peakHR | 12 | AT | DFI | 0.625 |

| Oka et al.30 | 12/12 | 53 (11.5) | 24.9 (8.7) | 15/25 | 5 | 70% peak HR/75% of 1RM | 12 | Multimodal | Dyspnoea-CHQ | 1.035 |

| Meyer et al.28 | 9/9 | 53 (6) | 21 (3) | 8/8 | 3 | 60% peakHR | 3 | AT | Borg | 0.000 |

| Weiner P et al.33 | 10/10 | 66.2 (14.6) | 24.7 (5.05) | NA | 6 | 60% of MIP | 12 | IMT | DI | 1.506 |

| Hossein Pour et al.32 | 42/42 | 56 (9.4) | 33.7 (6.1) | 32/52 | 7 | 40% MIP | 6 | IMT | MMRC | 0.957 |

| Bosnak-Guclu et al.29 | 14/16 | 69.5 (8) | 33.43 (7.23) | 20/10 | 7 | 20–30% MIP | 6 | IMT | MMRC | 0.771 |

| Seo et al.25 | 10/10 | 65.2 (11.3) | 35.2 (21.29) | 18/16 | 5 | Without resistance | 8 | IMT | KCCQ | 0.205 |

| Pozhen et al.34 | 15/6 | 66.3 (9.6) | 27.9 (7) | 8/13 | 3 | 60–85% peakVO2/1–10lb | 24 | Multimodal | DI | 1.240 |

| Van den Berg et al.26 | 16/16 | 58.6 (12.1) | 23.9 (9.40) | 20/14 | 2 | 60% HRR | 12 | AT | MLHFQ | 0.669 |

| Tanriverdi et al.35 | 17/17 | 63.7 (7.6) | 30.4 (4.5) | 22/12 | 3 | 30–70% MIP | 8 | IMT | MMRC | 0.811 |

| Evans et al.36 | 37/20 | 73.2 (8.9) | 30.7 (12.7) | 21/36 | 2 | 85% peakVO2 | 7 | AT | Dyspnoea-CHQ | 0.380 |

| Doletsky et al37 | 17/18 | 62.6 (9.8) | 29.3 (9.1) | 4/42 | 5 | 50% peak Watts | 3 | AT | MLHFQ | 0.780 |

| Delgado et al.24 | 143/110 | 67 (11) | NA | 0/232/45 | 5 | NA | 3 | AT | LCADL | 0.658 |

AT, aerobic training; EBCR, exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation; ES, effect size; IMT, inspiratory muscle training; n, number; IG, intervention group; CG, control group; SD, standard deviation; NA, not applicable; NYHA, New York Heart Association; F, frequency (sessions/week); T, time (length of the programme in weeks); Borg, Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion; DI, Dyspnoea Index; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; DFI, Dyspnoea-Fatigue Index; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; TDI, Transition Dyspnoea Index; MMRC, Medical Research Council; LCADL, London Chest Activity of Daily Living scale HR, heart rate; HRR, heart rate reserve; peakVO2, peak oxygen consumption; peakHR; peak heart rate, MIP, maximum inspiratory pressure; lb; pounds, 1RM, one-repetition maximum.

Fifteen RCTs with 766 HF patients were included, of which 2 studies23,24 reported patients with HFpEF, and 13 studies25–34 included patients with HFrEF. Most subjects belonged to classes II and III of the New York Heart Association scale (NYHA). The mean age of the samples ranged from 53 to 69.8 years. Of the trials, 2 examined the effects of multimodal EBCR, combining strength training with AT,30,34 5 studies examined IMT,25,29,32,33,35 and the other 8 only examined AT.23,24,26–28,31,36,37

Quality of studiesThe PEDro scores ranged from 4 to 8, with a mean score of 5. The weakest scoring area was the blinding of therapists and participants (criteria 5 and 6) and allocation concealment (criteria 3). Intention-to-treat analyses (criteria 9) were often not reported or poorly described (Table 2).

Risk of bias from the PEDro scale.

| Article | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total | Year | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gary et al.23 | x | x | x | x | 5/10 | 2018 | M | |||||||

| Beniaminovitz et al.31 | x | x | x | x | x | 5/10 | 2002 | M | ||||||

| Corvera-Tindel et al.27 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6/10 | 2004 | L | ||||

| Oka et al.30 | x | x | x | x | x | x | 5/10 | 2000 | M | |||||

| Meyer et al.28 | x | x | x | x | x | 5/10 | 1997 | M | ||||||

| Weiner P et al.33 | x | x | x | x | x | x | 5/10 | 1999 | M | |||||

| Hossein Pour et al.32 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7/10 | 2020 | L | |||

| Bosnak-Guclu et al.29 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6/10 | 2011 | L | ||||

| Seo et al.25 | x | x | x | x | x | 4/10 | 2016 | M | ||||||

| Pozhen et al.34 | x | x | x | x | x | 4/10 | 2008 | M | ||||||

| Van den Berg et al.26 | x | x | x | x | 4/10 | 2004 | M | |||||||

| Tanriverdi et al.35 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7/10 | 2023 | L | |||

| Evans et al.36 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 8/10 | 2010 | L | ||

| Doletsky et al.37 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6/10 | 2018 | L | ||||

| Delgado et al.24 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6/10 | 2022 | L |

Note: The Pedro Scale assigns up to a maximum of ten points for the least risk of bias based on (2). Random Allocation; (3). Covert Allocation; (4). Baseline Comparability; (5). Blinded Subjects; (6). Blinded Therapists; (7). Blinded Assessors; (8). Adequate Follow-Up; (9). Intention-To-Treat Analysis; (10). Between-Group Comparisons; (11). Point Estimates And Variability. The First Point (1) Eligibility Criteria Domains, does not compute in the total. Yes (x); No (empty). The Risk of Bias Based on Pedro was classified as Low Risk Of Bias (L), [6–10 Points], Moderate Risk Of Bias (4–5 Points) And High Risk Of Bias (0–3 Points).

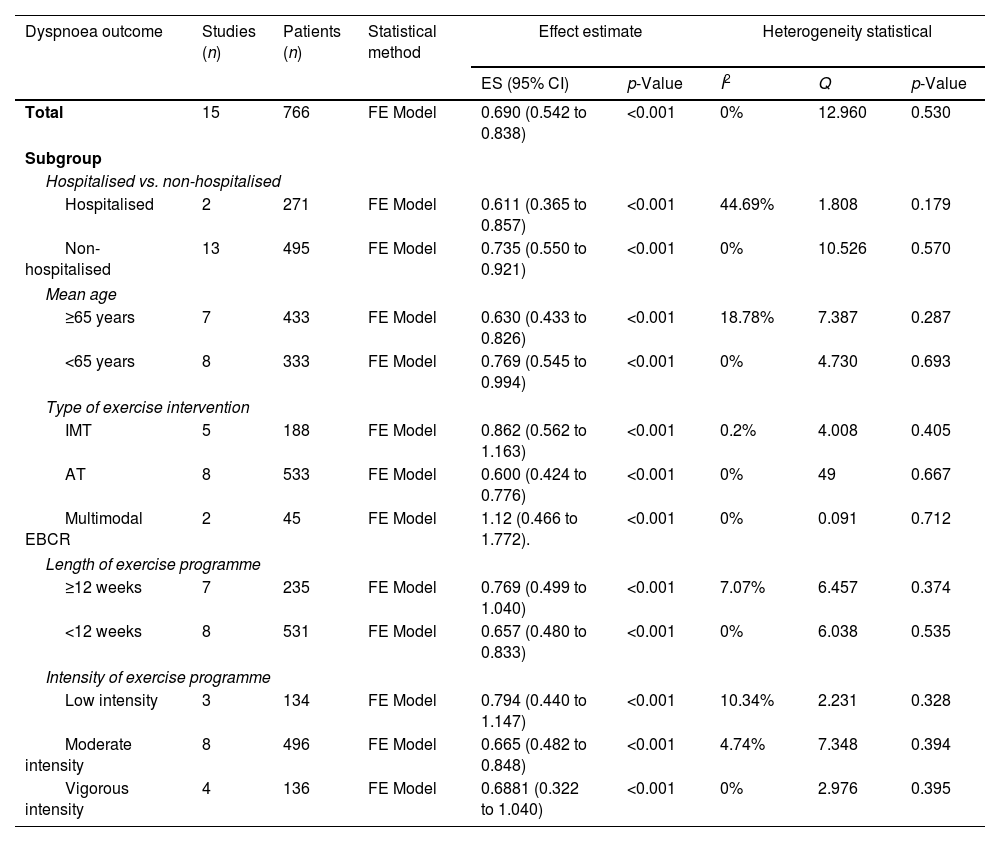

The results for dyspnoea symptoms are summarised in Table 3.

Summary results of the meta-analysis.

| Dyspnoea outcome | Studies (n) | Patients (n) | Statistical method | Effect estimate | Heterogeneity statistical | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES (95% CI) | p-Value | I2 | Q | p-Value | ||||

| Total | 15 | 766 | FE Model | 0.690 (0.542 to 0.838) | <0.001 | 0% | 12.960 | 0.530 |

| Subgroup | ||||||||

| Hospitalised vs. non-hospitalised | ||||||||

| Hospitalised | 2 | 271 | FE Model | 0.611 (0.365 to 0.857) | <0.001 | 44.69% | 1.808 | 0.179 |

| Non-hospitalised | 13 | 495 | FE Model | 0.735 (0.550 to 0.921) | <0.001 | 0% | 10.526 | 0.570 |

| Mean age | ||||||||

| ≥65 years | 7 | 433 | FE Model | 0.630 (0.433 to 0.826) | <0.001 | 18.78% | 7.387 | 0.287 |

| <65 years | 8 | 333 | FE Model | 0.769 (0.545 to 0.994) | <0.001 | 0% | 4.730 | 0.693 |

| Type of exercise intervention | ||||||||

| IMT | 5 | 188 | FE Model | 0.862 (0.562 to 1.163) | <0.001 | 0.2% | 4.008 | 0.405 |

| AT | 8 | 533 | FE Model | 0.600 (0.424 to 0.776) | <0.001 | 0% | 49 | 0.667 |

| Multimodal EBCR | 2 | 45 | FE Model | 1.12 (0.466 to 1.772). | <0.001 | 0% | 0.091 | 0.712 |

| Length of exercise programme | ||||||||

| ≥12 weeks | 7 | 235 | FE Model | 0.769 (0.499 to 1.040) | <0.001 | 7.07% | 6.457 | 0.374 |

| <12 weeks | 8 | 531 | FE Model | 0.657 (0.480 to 0.833) | <0.001 | 0% | 6.038 | 0.535 |

| Intensity of exercise programme | ||||||||

| Low intensity | 3 | 134 | FE Model | 0.794 (0.440 to 1.147) | <0.001 | 10.34% | 2.231 | 0.328 |

| Moderate intensity | 8 | 496 | FE Model | 0.665 (0.482 to 0.848) | <0.001 | 4.74% | 7.348 | 0.394 |

| Vigorous intensity | 4 | 136 | FE Model | 0.6881 (0.322 to 1.040) | <0.001 | 0% | 2.976 | 0.395 |

AT, aerobic training; CI, confidence interval; EBCR, exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation; FE, fixed-effect; ES, effect size; IMT, inspiratory muscle training.

Meta-analysis based on the fixed-effect model could be performed for comprehensive and subgroup analyses. The observed effect sizes ranged from 0.00 to 1.51, with most estimates being positive (91%). The estimated average effect size was d=0.69 (95% CI 0.54–0.89).

Subgroup analysis based on patient characteristicsLVEFA meta-analysis based on the LVEF phenotype of HF was not possible. Two studies23,24 demonstrated the effectiveness of EBCR on dyspnoea in HFpEF; nonetheless, the data needed to be sufficient to be meta-analysed.

Hospitalisation statusOnly 2 out of 15 of the studies included patients who had been hospitalised. Two analyses were performed depending on whether the EBCR programme was implemented in hospitalised or non-hospitalised patients. After analysis of the 2 studies24,28 conducted in hospitalised patients, EBCR showed a moderate effect size (d=0.61; 95% CI 0.36–0.857). When analysing the 13 studies23,25–27,29–37 that performed EBCR in non-hospitalised patients, a slightly larger effect size was shown (d=0.735; 95% CI 0.550–0.921).

AgeTwo analyses were performed based on the age of the HF patients. A moderate effect size (d=0.63; 95% CI 0.43–0.83) was observed after analysing the 7 studies23,24,27,29,33,34,36 with a mean patient age over 65 years. However, a slightly larger effect size was observed after analysing 8 studies26,27,30–32,35,37 whose mean participant age did not exceed 65 years (d=0.77; 95% CI 0.54–0.99).

Subgroup analysis based on FITT parametersSub-analyses were performed based on the FITT formula to extract the parameters within the most effective exercise programmes for dyspnoea.

IntensityThe most repeated intensity level in the studies was moderate intensity, followed by vigorous and low intensity. The intensity category varied depending on the type of intervention, with moderate, vigorous, and low being the most frequent intensity categories for AT, multimodal EBCR, and IMT, respectively.

Three analyses were performed according to the exercise intensity applied during EBCR. In the analysis of 3 studies25,29,32 with EBCR programmes performed at low intensities, a moderate-large effect size was observed (d=0.79, 95% CI 0.44–1.15). For EBCR programmes performed at moderate intensities, the analysis of 8 studies23,24,27,28,31,33,35,37 showed a moderate effect size (d=0.66, 95% CI 0.48–0.85). Finally, the effect size of EBCR programmes from 4 studies26,30,34,36 at vigorous intensities was moderate (d=0.68, 95% CI 0.33–1.04).

Monitoring intensityThe most used monitoring variable in the studies to verify the training intensity in AT was the % peakHR. At the same time, the IMT was % of MIP. % of 1-RM and the external load in pounds were used in those interventions, including strength training.

TimeThe duration of the programmes ranged from 3 to 24 weeks. The mean duration of the programme in weeks for AT, multimodal EBCR, and IMT was 8.00 (4.47), 18.00 (8.49), and 8.00 (2.45). The most repeated programme duration in the trials was 12 weeks.

Two analyses were performed according to the duration of the EBCR programmes. The 7 studies with more than 12 weeks23,26,27,30,31,33,34 showed a moderate effect size (d=0.77, 95% CI 0.50–1.04). The 8 studies24,25,28,29,32,35–37 with less than 12 weeks showed an effect size slightly smaller than the 12-week programmes (d=0.66, 95% CI 0.48–0.83).

Type of exercise interventionThree meta-analyses were conducted for studies whose intervention belonged to the same intervention category. A moderate effect size (d=0.60, 95% CI 0.42–0.78) was observed after analysing the 8 studies23,24,26–28,31,36,37 that included only AT.

However, a large effect size was reported in the analysis of the 5 studies25,29,32,33,35 that explored only IMT (d=0.86, 95% CI 0.56–1.16).

The analysis of 2 studies30,34 that included multimodal EBCR showed a larger effect size on dyspnoea than unimodal interventions (d=1.12, 95% CI 0.47–1.77).

Other FITT parameters were not included in the meta-analysisFrequencyThe frequency of the collected exercise programme interventions (weekly exercise sessions) was 2–7 sessions per week (sessions/week). The mean frequency of the programmes in sessions/week for AT was 3.5 (1.3) sessions/week; for multimodal EBCR, it was 4 (1.0) sessions/week; and for IMT, it was 5.4 (2.1) sessions/week. The most repeated frequency was 3 sessions/week, followed by 5 and 7 sessions/week. According to the type of intervention, the most repeated frequency in studies for AT and multimodal EBCR was 3 sessions/week; however, for IMT, the most repeated frequency was 7 sessions/week.

Session durationThe duration of the sessions ranged from 15min to 90min per session (min/session). The mean min/session for AT was 39 (20.1); for multimodal EBCR, it was 55 (7.1); and for IMT, it was 42.5 (32.0). The most frequent duration was 30min/session. The most repeated duration in AT and IMT was 30min/session, while in multimodal EBCR, it was 50min/session.

DiscussionThe present study aimed to analyse the effect of EBCR on dyspnoea in HF patients based on a meta-analysis. As the main finding, EBCR showed moderate effects on dyspnoea in patients with HF (Table 3). To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to provide results on the magnitude of the effect size of EBCR programmes on dyspnoea in the population with HF. Initial studies on exercise in HF patients demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of interventions on physical function parameters, including peakVO2, as well as addressing dyspnoea as a common symptom.38–40 Despite significant advancements in literature over the last decade, there remains a gap in the study of dyspnoea.7,8 Future studies should assess dyspnoea in exercise interventions to better understand the effects on this population.

Assessing dyspnoea continues to be a challenge for clinical research because of the heterogeneity found across studies and dyspnoea dimensions.11 In QoL questionnaires, such as MLHFQ and KCCQ, most studies reported the overall result, altering the interpretation of the dyspnoea measurement.7,8 Indeed, to interpret the results of dyspnoea outcomes, the instrument should be able to detect change. Only for the Borg scale, the minimal clinically important difference has been examined in HF with acute decompensation, but the assessment time frame limited its generalisation.8 Therefore, there is a need to generate a core set of dyspnoea assessment outcomes in HF. In this sense, it has been suggested to use unidimensional (e.g., Borg) alongside multidimensional scales to better understand the patient's experience.8 It could be valuable for prospective studies to evaluate the responsiveness of different dyspnoea scales following EBCR programmes.41

EBCR programmes had a moderate effect on patients under 65 years, and non-hospitalised. Concerning age, 8 clinical trials included patients under 65 years, possibly due to the number of patients with HF who can complete an EBCR programme. On the other hand, the difference between the effect of EBCR in hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients may be explained by the number of studies that included non-hospitalised patients (n=13 studies). The effect size in both cases is moderate, suggesting that EBCR is effective in both settings (Table 3). These results are consistent with previous reviews41–43 showing improvements in the KCCQ or MLHFQ scale, with EBCR independent of hospital status.

In our study, we pooled continuous aerobic exercise and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) in unimodal interventions of AT, which had shown a moderate effect on dyspnoea in HF. Several studies have demonstrated the benefit of EBCR programmes with AT in HF in central haemodynamic parameters, such as peakVO2, end-diastolic diameters and LVEF.43–45 However, the analysis of IMT showed a large effect (Table 3) on dyspnoea in HF. Previous meta-analyses obtained similar results when analysing the effect of IMT on dyspnoea in HF patients, in addition to relevant improvements in inspiratory force parameters (MIP) and spirometry.46 As with IMT, resistance training recently become one of the most popular forms of training against frailty and sarcopenia in older adults.47–49 Previous systematic reviews of HF patients43 have shown significant improvements in dyspnoea assessment scales, such as the MLHFQ, when HIIT was combined with strength training. Although the number of trials including multimodal EBCR programmes in this study was only two, both studies showed a large effect size, reflecting the potential benefits of using multimodal EBCR programmes to improve dyspnoea in HF.

Different effects of EBCR programmes on dyspnoea have been observed between patients with HF and other comorbidities. AT has shown moderate effects on dyspnoea in patients with HF, while in patients with COPD50 and pulmonary hypertension, AT had a larger effect on dyspnoea.51 In stroke, COPD, and pulmonary hypertension.52–54 Recent meta-analyses showed that IMT produced minimal improvements in dyspnoea despite moderate to significant effects on MIP values. In contracts, our study showed larger effects on dyspnoea with IMT in HF. Further investigation of the role of respiratory muscle strength, with the different forms of dyspnoea and HF phenotypes, may be relevant. Multimodal EBCR in COPD seems as effective as in HF, where a large effect size of combined training on dyspnoea was observed.55 Researching the relationship between strength and dyspnoea in different diseases could be promising.

As for clinical applicability, the present study describes the characteristics of patients responding to EBCR and the FITT exercise parameters that have shown the greatest improvements in dyspnoea. EBCR responders are non-hospitalised patients under 65 years, and the exercise dose (FITT) is 3 sessions/week, at low intensity, with durations longer than 12 weeks, and multimodal EBCR. Nevertheless, including exercise modalities and doses in this population will depend on the patient's environment.

Several limitations need to be considered in our analysis. Firstly, we only examined dyspnoea symptoms using Cohen's effect size due to the varied scales used in the included trials, so this highlights the need for better assessment tools for dyspnoea in patients with HF. Secondly, the analysis only focused on post-intervention results, as most studies did not provide pre-post data. Additionally, the meta-analysis was limited to studies that employed EBCR in the intervention and non-exercise control groups. Another limitation is the lack of trials examining the effect of EBCR on dyspnoea in patients with HFpEF and HFmEF. Finally, the conclusions drawn from our analysis were limited by the quality of the trials reviewed. Therefore, more high-quality RCTs, especially in very elderly patients and those with severe HF and HFpEF, are necessary to determine the benefits of EBCR in treating dyspnoea.

Ethical considerationsThis review article did not involve the collection of new data or direct intervention with human participants. All included studies were approved by the relevant ethics committees and complied with current ethical standards.

FundingCG-C is receiving a pre-doctoral grant from the University of Málaga. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Málaga/CBUA.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.