Marie Curie was born in Warsaw in1867. She graduated first in her class in her undergraduate programs in physics and mathematics at Sorbonne University, and she was one of the first women to earn a PhD. She was the first woman to win a Nobel prize (in physics, together with her husband, Pierre Curie), and she was also the first person to win a second Nobel prize in another category (chemistry).

Her life is an example of dedication to science based on altruism, personal growth, and tenacity. Being the first woman to break through so many barriers in a totally male-dominated science makes her an emblematic figure in the fight for equal opportunities and human rights.

This article reviews her most important contributions to science in general and to diagnostic radiology in particular through her participation in the French military’s radiological plan during the First World War.

Marie Curie nació en Varsovia en 1867, se licenció en Física y Matemáticas en la Universidad de la Sorbona, siendo la primera de su promoción, y fue una de las primeras mujeres en tener un doctorado. Fue la primera mujer en ganar un premio Nobel, en Física, junto a su marido Pierre Curie, y también la primera persona en obtener un segundo Nobel y en otra categoría: Química.

Su vida es un ejemplo de dedicación a la ciencia desde el altruismo, de superación personal y tenacidad. Fue la primera mujer en romper tantas barreras, en una ciencia hasta entonces masculina, que su figura constituye un hito en la lucha por la igualdad de oportunidades y los derechos humanos.

En este trabajo se revisan sus principales aportaciones a la ciencia y, en particular, al radiodiagnóstico a través de su participación en el plan radiológico militar francés de la Primera Guerra Mundial.

Maria Sklodowska-Curie was born in Warsaw on 7 November 1867 and spent her entire childhood in that city, then occupied by Imperial Czarist Russia. Since 1795, Poland had ceased to exist as a state. The internal destabilisation of the Commonwealth of Nations that it had upheld with Lithuania for two centuries gave way to anarchy and territorial vulnerability. After several partitions, it was ultimately annexed, carved up and distributed among Russia, Austria and Prussia.

The Russian Czarist regime exercised despotic power over the Polish population, whose autonomy was reduced to a minimum; efforts were even made to wipe the country's name off the map and replace it with Vistula Land. The Polish language was forbidden, and Russian was imposed as the language of administration, justice and secondary school.1

With this attempt at cultural assimilation, a strong Polish nationalist sentiment arose with historicist and religious (Catholicism) hallmarks deeply rooted in intellectuals and the middle classes, including the Sklodowski family.

Maria was the youngest of five siblings. Her mother, Bronislawa, studied education and came to direct an important boarding school for young ladies. She had to leave this position following the birth of the oldest of her daughters. Her father, Wladislaw, who had studied sciences at the University of Warsaw and directed two important secondary schools for boys in the capital, was tried in 1866 for his connection to nationalist circles that instigated the 1863−64 anti-Russian January Uprising. Accused of rebellion, he was relieved of any position of significance and relegated to a job as a physics and mathematics teacher at a secondary school in Warsaw. This represented a substantial loss of earnings for the family.2

The death of Maria's sister Zofia in 1876, two years after that of her mother, from tuberculosis, spurred her to grow up quickly. Her mother's death submerged her in a profound crisis of faith and led her to declare herself agnostic.

The young Sklodowski siblings completed their primary education at a semi-clandestine school where, alongside their required studies, they learned the Polish language as well as Polish history and culture. In 1878, Maria was admitted to the Sikorska boarding school. Later on, she studied at the Warsaw III Lyceum, where she graduated with highest marks (she was awarded a gold medal) in June 1883, a year early.

In the Russian Empire, women were barred from access to university. Maria was able to circumvent this ban through the Flying University (Uniwersytet Latajacy) of Warsaw, a private institution of higher education that had exclusively Polish teachers and students, and admitted female students. It was also founded by a woman: teacher, writer and activist Jadwiga Szczawinska-Dawidowa.3

As the name suggests, the Flying University was constantly relocating its clandestine classrooms, hidden in private homes, as a risky form of resistance to suffocating Russian cultural oppression. The university taught classes in Polish and instilled in its students ideas such as gender equality in education and abolition of class privileges. This institution taught thousands of students without resources and, in particular, women who had no other access to higher education. The Flying University and the courage of its instructors had a great impact on Maria, in particular on the development of her intellectual and philosophical ideology, helping to shape an enlightened and positivist spirit of activism for equal opportunities, without discrimination based on class or gender.4

In other countries in Europe, universities as illustrious as Sorbonne University in Paris, the University of Edinburgh and the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg had barely begun to accept women. Sorbonne University, founded in 1257 by Robert de Sorbonne and reformed by Cardinal Richelieu, did not open the doors of its then five faculties to women until 1860, six centuries after men.

Maria aspired to study in Paris to become a scientist, while her sister Bronia leaned towards medicine. As their family could not cover the costs of university and living outside of Warsaw for the two daughters, Maria and Bronia hatched a plan. First, Maria would remain in Warsaw and work as a private tutor to help pay for her older sister's degree. Then, once Bronia had completed her studies, she would use her own earnings to help cover the costs of Maria's studies.5

First years in France and research beginningsFollowing this plan, Maria arrived in Paris in autumn 1891 (Fig. 1), six years after Bronia had moved there and earned her degree in medicine with a specialisation in obstetrics and gynaecology. Maria was one of seven women enrolled that year in the Faculty of Sciences at Sorbonne University. Of the 1800 students at the university, 23 were women and most of these were studying medicine. She therefore entered a world that was doubly restricted for women: that of the university, and that of the sciences.

Just two years of study later, in July 1893, with her given name already gallicised, Marie not only became the first woman to receive a degree in physics from Sorbonne University, but also graduated at the top of her class. Not satisfied with that, and aware that a solid approach to any research in physics required a good foundation in mathematics, she set about earning a second degree in mathematics within a single year. The primary obstacle was, once again, economic, but that summer, she would travel to Poland, where she had been awarded the Alexandrovich Scholarship for the best Polish students abroad. The 600 roubles in award money enabled her to spend another year in Paris and earn her mathematics degree without hardship.6

When she returned to Paris in the autumn, her lecturer Gabriel Lippmann (one of the most respected physicists of the time and a future Noble prize winner) received her with the news that she had got her first paid job as a researcher. Under his tutelage, Marie was to study the magnetic properties of steel for the Society for the Development of National Industry (Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale), for which she would be rewarded with 600 roubles, the exact amount she had received for the Alexandrovich Scholarship. The youngest Sklodowski broke the mould once again, becoming the first Polish student to give up the scholarship and refund the amount so that somebody else could benefit from it.7

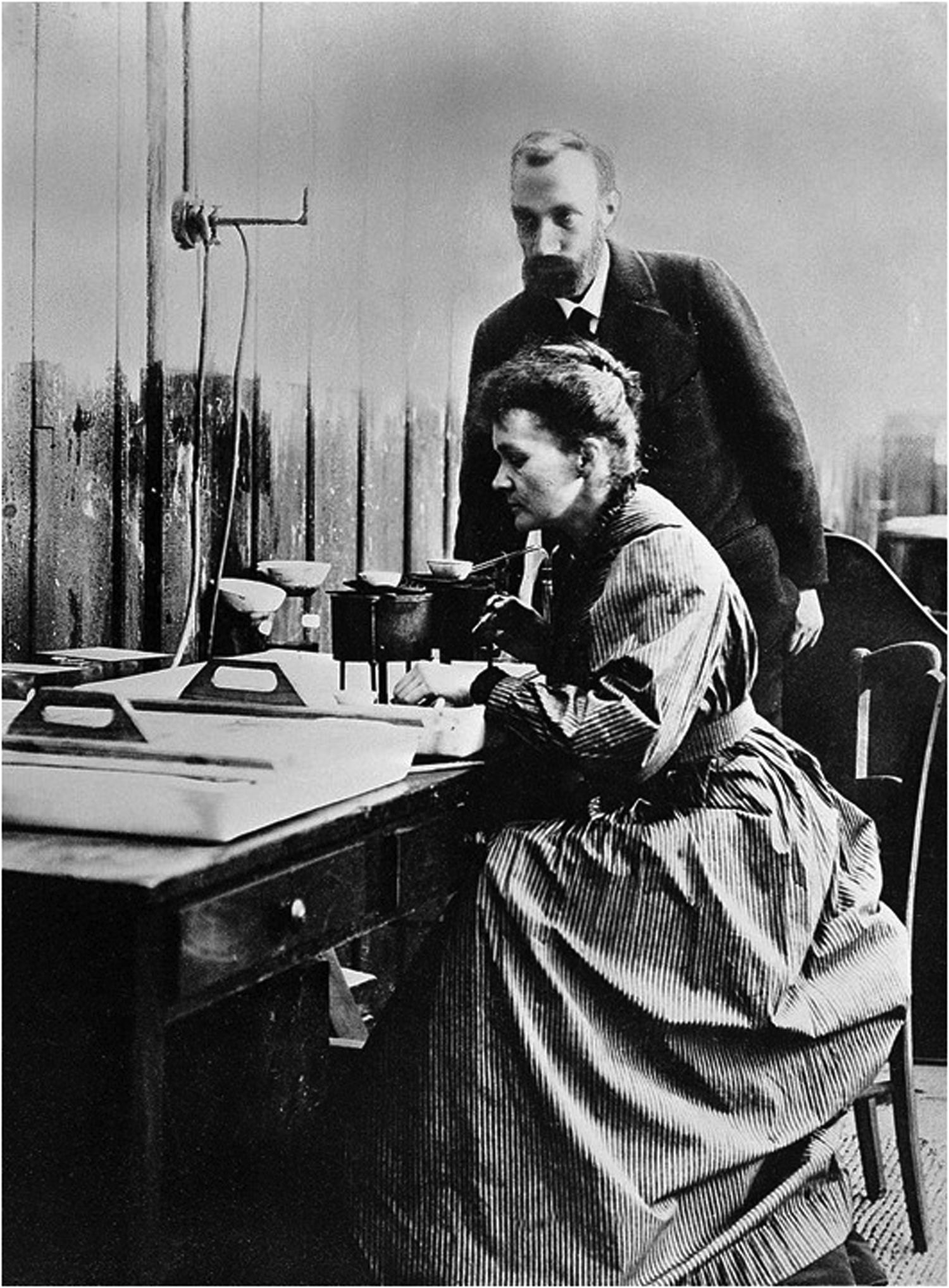

As a result of her work for the Society for the Development of National Industry and problems of limited workspace at the Sorbonne laboratory, Marie would meet Pierre Curie (Fig. 2). Her future husband was a lecturer at the City of Paris Industrial Physics and Chemistry Higher Educational Institution (École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la Ville de Paris) and as such had a laboratory that the young lady from overseas requested to use for conducting research.8

The attraction between the two was immediate. They shared their passion not only for science and the scientific method as a true source of knowledge, but also their conviction that science should be used to dominate nature for humanitarian purposes and thus improve the lives of people; this philosophical position is known as positivism.9,10

The couple married in Paris on 26 July 1895. This year was, of course, significant in the history of medicine for another reason. German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen's experimentation with cathode rays led him to discover a new form of light capable of passing through objects. He himself called them X-rays, referencing their unknown nature.

After he analysed their properties and published his discovery, which would earn him the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901, the news spread throughout the world and X-rays became a popular phenomenon, primarily due to their recreational applications. The public paid to have X-rays taken of them for fun at carnivals and fairs, before their harmful effects on the body became clear. At the same time, the first medical applications of X-rays did not take long to develop, starting with the use of X-rays to examine bone fractures and, shortly thereafter, chest diseases. Barely a year after Bertha Röntgen's hand was X-rayed, nearly 50 books and more than 1000 articles on the new discipline of medical radiology had already been published.

As a result of Röntgen's discovery, French physicist and chemist Antoine-Henri Becquerel started to study phosphorescent substances to determine whether they, too, emitted X-rays when exposed to sunlight. To do this, he used uranium salts on photographic plates. He discovered that these not only emitted radiation, but also did not require accumulated solar energy to do so. This went in the face of the knowledge of the time. According to the principles of classical physics, expressed in Parmenides' maxim ex nihilo nihil fit ("nothing comes from nothing"), radiation could not emanate directly from the salts without a power source.11

Marie Curie saw in this discovery a fascinating topic for her doctoral dissertation. In December 1897, she began researching those uranium rays with the goal of tearing down a new barrier and becoming the first woman to earn a doctorate degree in physics.12,13

The Nobel PrizesMarie discovered that the intensity of radiation did not depend on the structure of the compound, nor did it result from a chemical reaction between its molecules; rather, it was proportional only to the quantity of the element, since it was an intrinsic quality characteristic of the atom itself. Marie christened this property "radioactivity", a term of Latin origin meaning "emitting rays".14,15

Her observation that the crude form of uranium oxide known as pitchblende produced radioactivity 300 times greater than corresponded to its uranium content led the scientist to deduce that pitchblende must contain small amounts of some other highly radioactive element that was unknown. Following arduous chemical analyses, she managed to purify small traces of the new, highly radioactive metal element. Marie and Pierre gave an account of their finding at the French Academy of Sciences (Académie des sciences) in Paris in July 1898, and proposed that it be named polonium, in honour of Marie's native country.16

The Curies carried on with their efforts to chemically separate pitchblende, and in early November they recognised the presence of a second unknown substance with radioactivity thousands of times greater than that of uranium. They called the new element radium (from the Latin radius, meaning ray) and reported its existence to the Academy in December 1898.17

With her work, Marie Curie earned not only a doctorate degree, but also the Nobel Prize. She defended her doctoral dissertation in June 1903 and earned the degree of Doctor of Physics cum laude. The telegram from Stockholm announcing that they and Becquerel had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their work on radioactivity reached the Curies' home in November of that year. Marie was the first female scientist to be awarded a Nobel Prize by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.18

Pierre Curie died on 18 April 1906 when he was run over by a carriage. His daughters Irène and Ève were eight and two years old, respectively.19

In November 1911, a new telegram arrived from Sweden informing Marie that she had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in recognition of her work isolating pure radium.20

Between 1902 and 2020, this prize, conferring maximum international prestige, was awarded to 873 men and 57 women. The first woman to receive it was Marie Curie in 1903. She is also the only woman to have won it more than once. Of the 57 women awarded a Nobel Prize, just 11 have received one in physics or chemistry. One of them was Irène Joliot-Curie, the older daughter of Pierre and Marie, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935 along with her husband Frédéric Joliot for their synthesis of new radioactive elements. Marie and Irène are the only mother and child to have received a Nobel Prize. At present, Marie Curie remains the only person in the history of the Nobel Prizes to have been awarded two in different areas of science: physics in 1903 and chemistry in 1911.20

World War I and radiologyWhen World War I began in 1914, the altruistic Polish researcher, who, like Röntgen, had decided not to patent her experiments so that any interested party could make use of them freely, wondered how a scientist like her could help now. Between two possible pathways, seeking new scientific applications to war needs and contributing to efforts to organise already available resources, she chose the latter.21

This decision inaugurated a new, frenetic stage in her life and led her to figure among the memorable pioneers of diagnostic radiology, in addition to her above-mentioned merits. The French Ministry of War named Marie director of the Radiology Department of the Red Cross; in that capacity, she decided to comb Paris for all the radiology equipment she could find. Her work was to consist of organising radiology departments in war hospitals.22

At the beginning of the last century, surgeons at field hospitals did piecework, attempting to operate blindly on truly gory wounds in a race against the clock. The benefits of X-rays in war were obvious from the outset. Thanks to X-rays, surgeons knew, before beginning the operation, the location and type of bone lesion, and the number and location of bullets and pieces of shrapnel without first probing the soldiers' wounds. This reduced intraoperative time, minimised harm and decreased mortality.

The problem was that it was very difficult to move X-ray equipment to the front lines, as Antoine Béclère, another pioneer of radiology remembered for his work on fluoroscopy and for having coined the term "radiologie" in France, explained to Marie in 1914. For that reason, and because there was not enough X-ray equipment to cover all the front lines, its use was limited.23

Installation of radiology equipment at rear hospitals and even at field hospitals was also not a solution for many wounded soldiers, especially the most seriously injured, who were at risk of losing their lives in transfer. These soldiers had to be cared for on the front lines themselves; this required not only moving equipment to the trenches, but also connecting it to electricity for it to work. The inventiveness of a Spanish engineer proved opportune in resolving this double bind.

Mónico Sánchez, born in Piedrabuena (Ciudad Real) in 1880, was an electrical engineer and a prolific inventor who broadened his professional training and experience in New York and became head engineer of the Collins Wireless Telephone Company. He and his company participated in international fairs alongside Edison's General Electric and Tesla's Westinghouse. He eventually returned to Spain and founded his own company. Despite being little known, Sánchez shares with these figures a prominent place among the pioneers of wireless telecommunications and electromedicine.

The La Mancha engineer's most outstanding invention was a portable X-ray device that owed its worldwide success to both its qualities and the historical circumstances of the time. The device, which was easy to transport and handle and weighed barely 10 kg, was capable of powering a conventional X-ray tube. In 1914, France commissioned more than 50 of them to be installed in the ambulances that served the front lines during World War I.

Marie grasped their enormous potential for diagnosing wounds on the front lines and endorsed, extended and systematised their use. In September, the first X-ray unit cared for wounded soldiers in the First Battle of the Marne against the German army (in which 400,000 died). In an affectionate nod and tribute to Madame Curie, those peculiar trucks were called "petites Curie" (little Curies) (Fig. 3). The vehicles, simple, light and easy to drive, were fitted with X-ray equipment, a darkroom for processing and a dynamo to generate the electricity required using the truck's petrol engine. Fully loaded, their top speed was no more than 30 km/h.

Between October 1914 and late 1916, Marie visited dozens of hospitals with her petites Curie. However, radiology departments lacked qualified technicians. This new hurdle started to come down in 1916, when she got the green light from the Health Department to begin training technical personnel. After a few months at a provisional centre, classes were then taught at the Radium Institute. This institute, planned shortly before World War I, had been reconverted thanks to Marie's hard work and grace into a radiology school, where she taught lessons on X-rays. Another effect of the conflict was that the hospital–school was filled with women, since most men had been drafted. One of the most valuable sources of support among these women, both at school and on expeditions with petites Curie, was her older daughter Irène, who joined the team despite being only 17 years old (Figs. 4 and 5).24

Marie's endeavours were not limited to transporting equipment; she also worked as a technician and trained military personnel. She herself completed more than 1200 radiological examinations. In view of the lack of drivers, she got a driving licence and learned the fundamentals of mechanics in 1916, when she was 49 years old. On one of her trips, she suffered an accident that left her battered and bruised. "I can never forget that destruction", she wrote. "Men and boys covered in a mix of mud and blood."25

However, the military looked unfavourably on civilians prowling the front lines, and more unfavourably still on those who were women. The arrival of Marie and Irène was not always well received. Moreover, the doctors of the time, especially the most experienced, remained reluctant to use X-rays as a diagnostic tool, especially with a young woman like Irène operating the device. She determined the location of the bullet or shrapnel on X-ray and performed mathematical calculations to determine its spatial location in the affected anatomical region, then showed them to surgeons and made suggestions as to where to operate. These suggestions were often met with rejection or suspicion. However, the efficacy of X-rays managed to erase any trace of objection.26

When the war ended in November 1918, the fleet of petites Curie totalled 20 vehicles and 175 operators. Between 1917 and 1918, 1,100,000 documented X-rays were taken.27

Marie Curie left a testimony to the contributions of radiology in those dramatic years, which also served as a definitive consolidation of those contributions, in a new book entitled "La radiologie et la guerre" [Radiology and War].28 In this book, she set out the problems in radiology that were encountered during the war and their solutions, such as the assembly of mobile posts that could be transported from the hospitals to the front lines, the training of specialised personnel and the ways in which fractures and locations of projectiles were examined.

In "La radiologie et la guerre", Marie reflected on locating foreign bodies, diagnosing fractures and radiology in general (Figs. 6–10): "This is a wonderful method of observation, indeed—one that enabled us for the first time to examine the inside of the human body without the help of surgery. […] If a metal object has entered the body after an injury (a bullet or shrapnel), the presence of this object inside the body is revealed on fluoroscopic or X-ray imaging through the shadow that it casts. […] If a broken bone appears on the image, the X-ray will reveal the details of the accident. […] This creates a wonderful opportunity for diagnosis by direct visualisation, which benefits the patient and relieves the physician of some responsibility."

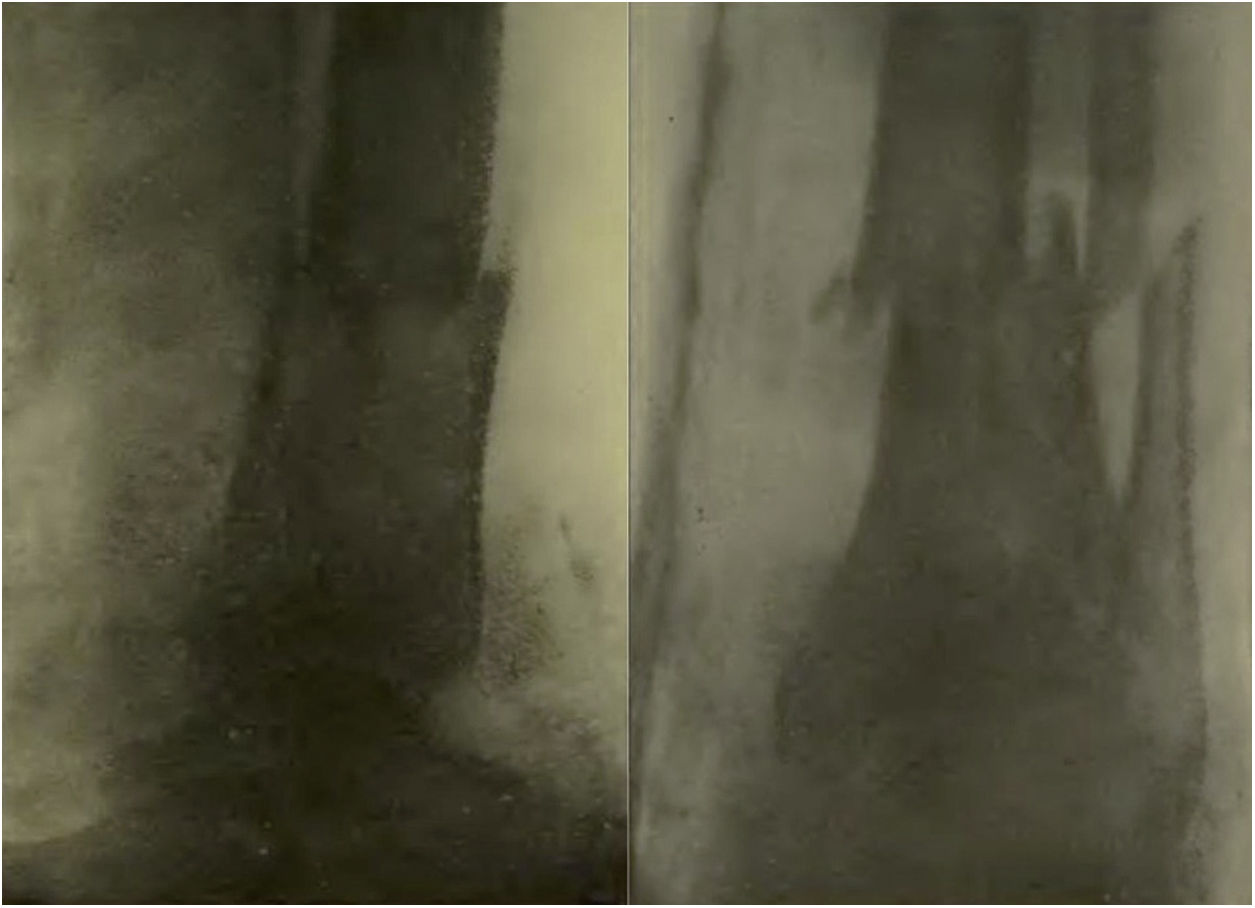

X-ray of a shoulder from the book "La radiologie et la guerre". The book describes the image thus: "The parts closest to the plate produce sharp, narrow shadows; the parts farthest from the plate produce less sharp, broad shadows."28

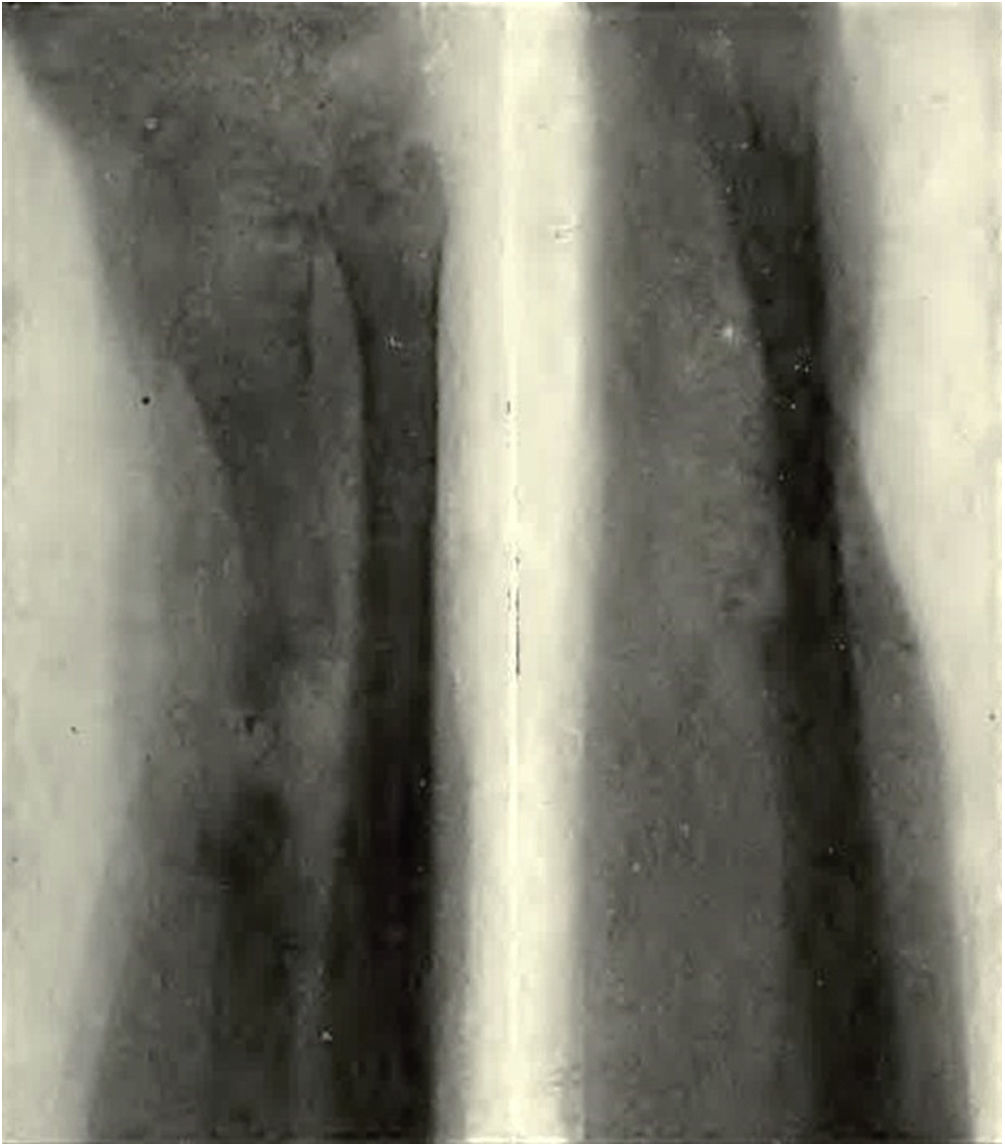

X-ray of a leg in a cast. Fracture of both bones (tibia and fibula) with displacement.28

X-ray of a forearm. Radius fracture with loss of substance.28

X-ray of a forearm. Consolidated radius fracture callus.28

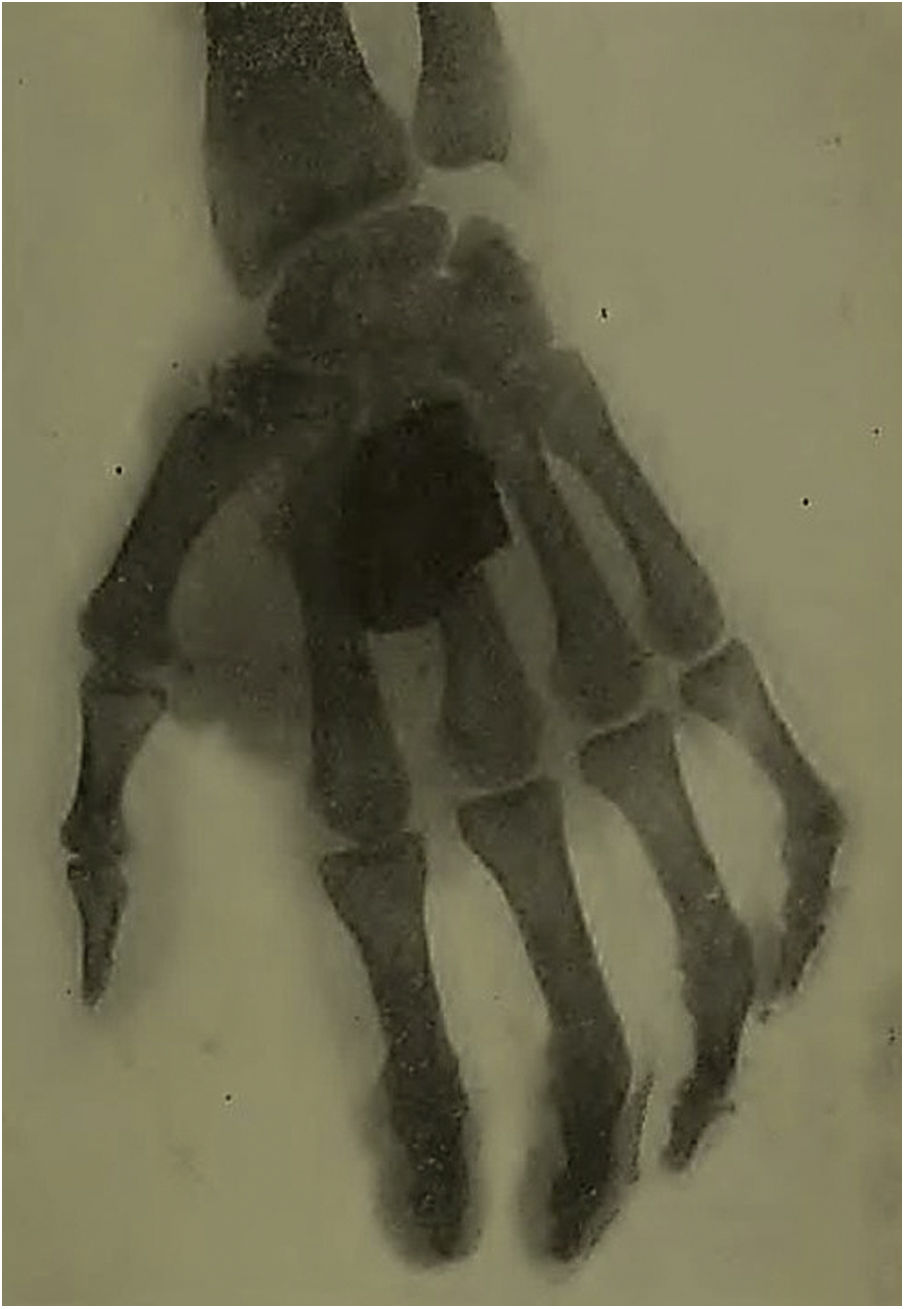

X-ray of a hand. The X-ray revealed the presence of a large piece of shrapnel. Fractures of carpal and metacarpal bones.28

Later, she reiterated the importance of removing foreign bodies to prevent complications and anticipated the role of radiological imaging in planning surgical procedures: "In fact, foreign bodies in the body are a common cause of abscesses, either because they carry infectious germs or contaminated dirt or debris from clothing, or even simply because contact with them irritates tissue and prevents healing. On the other hand, when the wound is new, the open path often makes removal very easy; the surgeon can follow the path without further damage, aided by radiological examination; in many cases, the surgeon can remove one or more foreign bodies from the wound within a couple of minutes."

She also mentioned technical matters, such as the usefulness of two orthogonal projections in bone X-rays, and touched on organisational considerations, such as the utility of image archiving and radiological monitoring over time: "To arrive at a correct opinion on bone fractures, it is useful to take two X-rays on different planes—for example, a frontal view and a lateral view, when the injured can be moved. The X-rays obtained are stored as documents. It is also useful to take a new X-ray from time to time to monitor the progress of healing, or to demonstrate the outcome of surgery in clearing the fracture site of foreign bodies and to correct the position of the bones. All of these X-rays reproduce the history of the injury. Sometimes it is painful history, but more often it is comforting because persistent effort greatly improves seemingly hopeless cases."

Ultimately, based on this application of radiology to a specific area, she reached a general conclusion that the passage of time has but corroborated its use and increased its validity up to the present. Marie concluded: "Radiology is essential. This truth, which was not widely known at the beginning of the war, is no longer questioned by anyone today, and no surgeon would agree to begin surgery in the present day without being aware of the information provided by the radiologist."28

She died of aplastic anaemia in 1934, when she was 66 years old. For decades, it was believed that this disease had been caused by her prolonged exposure to radiation.29

However, when a decision was made to transfer her remains, along with those of Pierre, to the Panthéon in Paris in 1995, technical reports indicated that her disease was "probably" more related to her work with X-rays during the war. She is said to have performed hundreds of tests without wearing proper protection, despite always advising her colleagues and students to do so.30

If true, this would only increase her honour along with those who, in the words of Béclère, sacrificed their lives to fight disease and suffering with the wonderful weapon that Röntgen contributed to medicine.

ConclusionsThe life of Marie Curie is an exceptional example of altruistic dedication to science in the 20th century, an era of extraordinary and revolutionary discoveries, including her own. To do this, she had to use her courage, intelligence and tenacity to overcome highly unfavourable conditions as a Pole, as a scientist and, above all, as a woman. With the firm and vital conviction that nothing was impossible to achieve by mere virtue of being a woman, she was the first to break so many barriers in an up-to-then male-dominated science. Her life therefore represents a milestone in the fight for equal opportunities and human rights.

This study reviewed her primary contributions to science and, in particular, the definitive dissemination of diagnostic radiology through her participation in the French military radiology plan in World War I. The small vehicles equipped with portable X-ray equipment travelled paths of mud and blood to care for victims. In many instances, they were driven by a woman of mature age who had received two Nobel Prizes. They are pieces of radiology history.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: RSO, JTN, MLFB, GMS.

- 2

Study concept: RSO, JTN.

- 3

Study design: RSO, JTN, MLFB, GMS.

- 4

Data collection: not applicable.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: not applicable.

- 6

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7

Literature search: RSO, JTN, MLFB.

- 8

Drafting of the study: RSO, JTN, MLFB, GMS.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: RSO, JTN, MLFB, GMS.

- 10

Approval of the final version: RSO, JTN, MLFB, GMS.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Oro R, Torres Nuez J, Fatahi Bandpey ML, Martínez-Sanz G. Marie Curie: Cómo romper el techo de cristal en la ciencia y en la radiología. Radiología. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2021.04.004