Transarterial embolization (TAE) is the gold standard treatment for iatrogenic renal artery pseudoaneurysms (PSA) and pseudoaneurysms with arteriovenous fistula (PSA + AVF), but its impact on renal function has not been sufficiently investigated. The aim of the study is to assess the impact on of TAE on renal function and its technical and clinical effectiveness.

Materials and methodsSixty-seven embolization procedures in 61 consecutive patients from December 2006 to October 2020 in two centers were retrospectively reviewed for the following parameters: technical and clinical success and failure, embolization materials, type and dimensions of vascular injuries, percentage of post-procedural ischemic renal parenchyma and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) values before and 1 day after the surgical, percutaneous or endoscopic (SPE) procedure and before, 1 day after and 6 months after TAE.

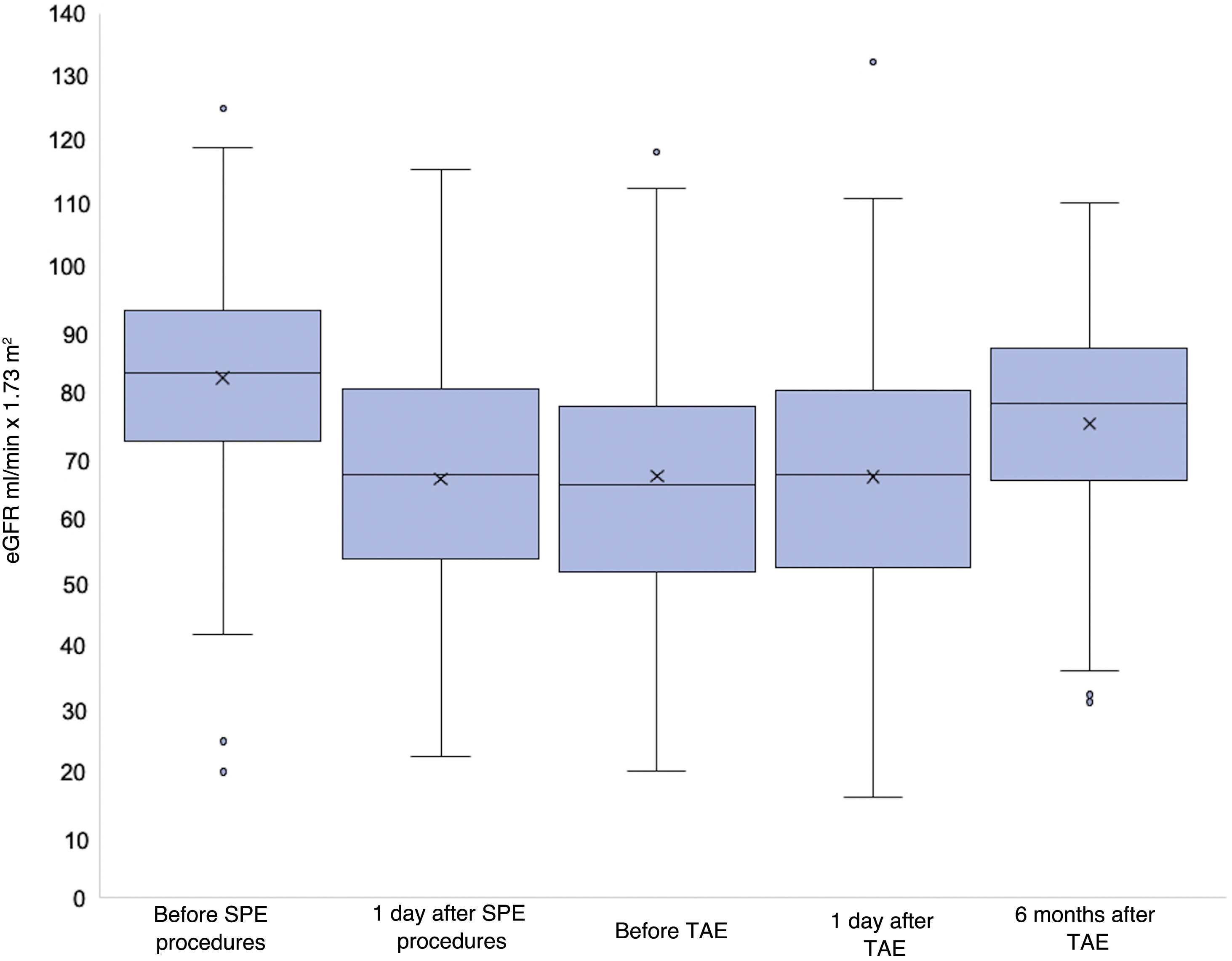

ResultsWe identified 44 PSA and 23 PSA + AVF. Technical success was 95.5%, primary clinical success was 90.2% and secondary clinical success was 96.7%. Different embolization materials were used. A significant decrease of the eGFR was found after the SPE procedure. No significant difference was found between eGFR before and after TAE. A minimal significant improvement of the eGFR was found 6 months after TAE. Embolization of larger lesions resulted in larger post-procedural ischemic areas. PSA + AVF were significantly larger (p = 0.0142) and determined a larger post-procedural ischemic area. No correlation was found between dimensions, kind of vascular injury or post-procedural ischemic area and eGFR.

ConclusionTAE has high technical and clinical success rates and does not affect renal function negatively, regardless of dimensions or kind of vascular injuries or post-procedural ischemic area.

La embolización transarterial (ETA) es el tratamiento de referencia de los pseudoaneurismas (PSA) yatrógenos de la arteria renal y de los pseudoaneurismas yatrógenos de la arteria renal con fístula arteriovenosa (PSA + FAV), pero su efecto sobre la función renal no se ha investigado lo suficiente. El objetivo del estudio es evaluar el efecto de la ETA en la función renal, así como su eficacia técnica y clínica.

Materiales y métodosSe revisaron retrospectivamente 67 procedimientos de embolización en 61 pacientes consecutivos desde diciembre de 2006 hasta octubre de 2020 en dos centros para determinar los siguientes parámetros: éxito y fracaso técnico y clínico, materiales embolizantes, tipo y dimensiones de las lesiones vasculares, porcentaje de parénquima renal isquémico tras el procedimiento y valores de la filtración glomerular estimada (FGe) antes y 1 día después del procedimiento quirúrgico, percutáneo o endoscópico (QPE), así como antes, 1 día después y 6 meses después de la ETA.

ResultadosIdentificamos 44 PSA y 23 PSA + FAV. El éxito técnico fue del 95,5%, el éxito clínico primario del 90,2% y el éxito clínico secundario del 96,7%. Se utilizaron diferentes materiales embolizantes. Se observó una disminución significativa de la FGe tras el procedimiento QPE. No hubo diferencias significativas entre la FGe antes y después de la ETA. Se observó una mejoría mínimamente significativa de la FGe 6 meses después de la ETA. La embolización de lesiones de mayor tamaño dio lugar a áreas de isquemia más extensas después del procedimiento. Los PSA + FAV fueron significativamente mayores (p = 0,0142) y provocaron un área de isquemia de mayor tamaño después del procedimiento. No se observó ninguna correlación entre las dimensiones, el tipo de lesión vascular o el área de isquemia después del procedimiento y la FGe.

ConclusiónLa ETA tiene unas tasas elevadas de éxito técnico y clínico y no afecta negativamente a la función renal, independientemente de las dimensiones o el tipo de las lesiones vasculares o del área de isquemia después del procedimiento.

Over half of renovascular lesions causing haematuria are iatrogenic in origin.1

Iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms (PSAs) and pseudoaneurysms with arteriovenous fistula (PSAs + AVF) of the renal artery are rare, with a prevalence of 2% and unknown, respectively.2 A PSA is defined as a breach to the vascular wall, resulting in abnormal blood flow through the intima and media, contained only by the adventitia or the surrounding tissues (rupture).3 A renal arteriovenous fistula (AVF) is an abnormal communication between a renal artery and a branch of a renal vein.

Nephron-sparing surgery (NSS) is one of the most common causes of these renovascular lesions.2,4,5 Other possible causes include nephrostomy, lithotripsy, pyelolithotomy, renal biopsy, and the placement of renal stents.6–10

PSAs and PSAs + AVF typically present with pain in the renal fossa, visible haematuria, and anaemia.2

Transarterial embolisation (TAE) is the gold standard treatment because it is safe, minimally invasive and provides an efficient way to locate the bleeding site and achieve haemostasis.11

The effect of TAE on renal function has not been extensively studied. The literature only addresses this aspect partially as it focuses more on creatinine levels than estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Moreover, most studies are based on relatively small series.6,7,11–18 No studies examine the relationship between the size of PSAs and PSAs + AVF or the type of vascular lesion and the area of ischaemia after TAE.

Here we present a retrospective observational study that evaluates the effect of TAE on renal function when performed on iatrogenic renal artery PSAs and PSAs + AVF both immediately after the procedure and at a relatively long follow-up period (six months). It also assesses the impact of TAE on the area of renal ischaemia after the procedure, as well as its technical and clinical efficacy as a first-line treatment.

Materials and methodsPatientsWe retrospectively reviewed the clinical and imaging data of all patients who underwent embolisation for iatrogenic renal PSAs and PSAs + AVF between December 2006 and October 2020 at two centres in the same country (UOC Radiologia 2, Azienda Ospedale Università Padova, Padua, Italy; UOC Radiologia, Ospedale di San Bassiano, Bassano del Grappa, Vicenza, Italy). 55 patients were treated at the former and six at the latter.

The procedures which gave rise to the formation of a PSA or a PSA + AVF have been grouped in this document under the acronym SPE (surgical, percutaneous or endoscopic). ‘S’ indicates a surgical intervention (open, laparoscopic or robot-assisted nephron-sparing surgery, enucleorresection, etc.), ‘P’ indicates a percutaneous procedure on the kidney (nephrostomy, biopsy, etc.) and ‘E’ indicates an endoscopic procedure on the kidney (pyelolithotomy, endoscopic lithotripsy, etc.).

Inclusion criteria for angiography and embolisation were based on both clinical features (haematuria, worsening anaemia, haemodynamic instability or haemorrhagic shock) and imaging features (visualisation of bleeding on contrast-enhanced computed tomography [CCT]).

All patients signed an informed consent for the embolisation procedure.

Pre-procedural diagnostic imagingAll patients had a CCT scan as the baseline imaging test (Lightspeed VCT, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA; and SOMATOM Sensation, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). We injected 50–80 ml of non-ionic iodinated contrast medium (Omnipaque 350, GE Healthcare, USA; Ultravist 370, Bayer Healthcare, Brussels, Belgium; and Iomeron 400, Bracco, Bracco, Milan, Italy) at a concentration of 350–400 mg I/mL into an antecubital vein at a flow rate of 3.5–5 ml/s followed by a bolus of 30–40 ml saline solution at the same injection rate with an automatic dual-head injector (Stellant D, Medrad, Bayer Healthcare, Whippany, NJ, USA).

We obtained images in the pre-contrast, early arterial, venous and excretory phases. The timing of the early arterial phase was determined by the bolus tracking technique by placing the region of interest (ROI) at the level of the suprarenal abdominal aorta with an enhancement threshold of 100 HU (Hounsfield units). The venous phase was performed with a delay of 70 seconds after the arterial phase, and the excretory phase was acquired after 8–10 min.

Multiplanar reconstructions (coronal and sagittal) were obtained and sent to the picture archiving and communication system (PACS).

On CCT, a PSA was identified when an enhanced cavity was detected in direct communication with an injured renal arterial branch in the early arterial phase. It was differentiated from an active haemorrhage with a subcapsular or perirenal haematoma because a PSA is a well-defined dense accumulation of contrast medium similar to arterial enhancement, contained by the adventitia or connective tissue. Active contrast extravasation is visualised as a poorly defined area of enhancement (blush) or a focal region of hyperattenuation within a haematoma, which diffuses into an enlarged and enhancing haematoma, with potential layering visible on delayed scans.19

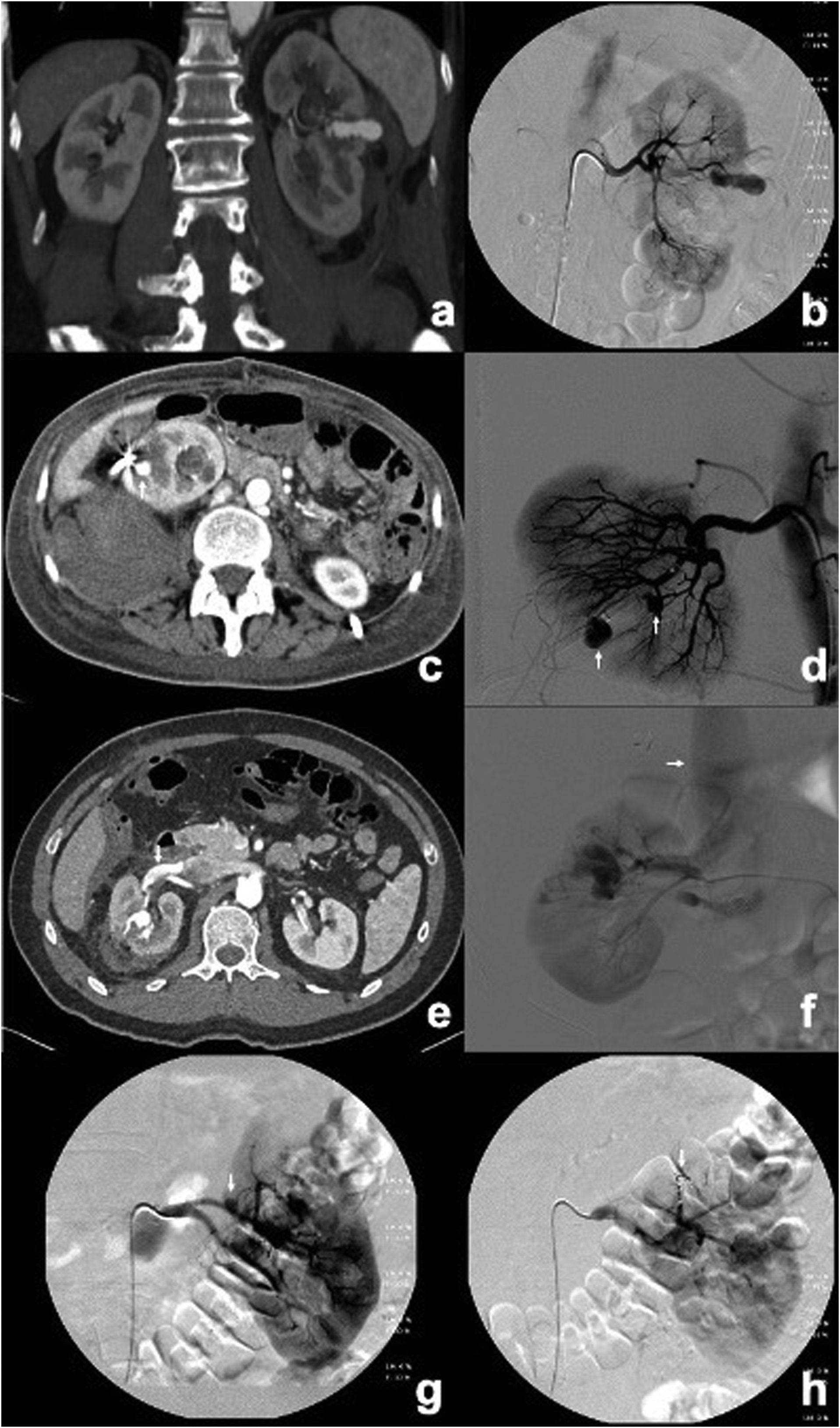

AVFs were identified when direct communication was observed between an arterial branch and a venous branch, or by enhancement of the renal vein or inferior vena cava in the early arterial phase (Fig. 1).

CCT and angiograms showing PSAs and PSAs + AVF. (a, b) CCT in arterial phase and angiogram showing a large PSA in the middle third of the left kidney after NSS. (c) CCT showing only one PSA in the lower pole of the right kidney (arrow) following the placement of a nephrostomy catheter. (d) Angiogram of patient in (c) indicating two PSAs (arrows). (e) CCT showing a PSA in the middle third of the right kidney associated with an early enhancement of the ipsilateral renal vein (arrow), compatible with an AVF after NSS. (f) Angiogram confirming the presence of a PSA + AVF in the patient and early opacification of the inferior vena cava (arrow). (g, h) Angiograms showing a PSA in the upper pole of the left kidney following NSS before and after embolisation with coils (arrow), with exclusion of the PSA and minimal parenchymal loss (0–20%).

An experienced interventional radiologist performed the embolisation procedures in an angiography suite.

A percutaneous puncture of the common femoral artery was performed with the placement of a standard 5 F sheath (Radifocus, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). With a diagnostic 5F catheter (RDC or Cobra or Simmons, Tempo Aqua, Cordis, Miami, FL, USA; or Glidecath, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) we performed selective catheterisation and diagnostic angiography of the main renal artery. Once the intrarenal target vessel was identified, superselective catheterisation was performed using a coaxial technique with a 2.7F microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). In all cases of unstable catheterisation, we used a coaxial technique with a guiding catheter (RDC or HS Vista Brite, 7F, Cordis, Miami, FL, USA; Contra, 8F, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA).

The aim of the embolisation was to minimise the amount of sacrificed renal parenchyma by administering the embolic material as distally as possible. We used microcoils (Vortx, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA; Tornado, Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) implanted via a bolus injection of saline solution or a coil pusher device (Coil pusher, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), detachable microcoils (Concerto, ev3, Covidien, Plymouth, MA, USA), Spongostan (Spongostan, Johnson & Johnson Ethicon Inc, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles (Contour Emboli, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), or cyanoacrylate glue with ethiodised oil (Glubran 2, GEM, Viareggio, Italy; Lipiodol Ultra Fluid, Guerbet, Villepinte, France). The choice of embolic material was based on both the target lesion and the experience of the interventional radiologist.

After administrating the embolic material, we performed digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the affected kidney to confirm the exclusion of the vascular lesion.

Procedural resultsTechnical success was defined as the complete occlusion of the target vessel with no bleeding or visualisation of a PSA or a PSA + AVF on the final DSA.

Technical failure was defined as the inability to complete the procedure, incomplete exclusion of the vascular lesion, or persistence of the PSA + AVF on the final DSA.

Clinical success was considered the outcome when patients showed improvement in both symptoms and laboratory markers.

Clinical failure was defined as the persistence of symptoms and the worsening of laboratory data, indicative of ongoing vascular lesion.

We used the CIRSE classification system as a guideline for reporting and classifying complications.20

Renal function was assessed prior to and one day after the SPE procedure as well as prior to, one day after, and six months after the embolisation procedure, using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula to determine eGFR (ml/min × 1.73 m2).

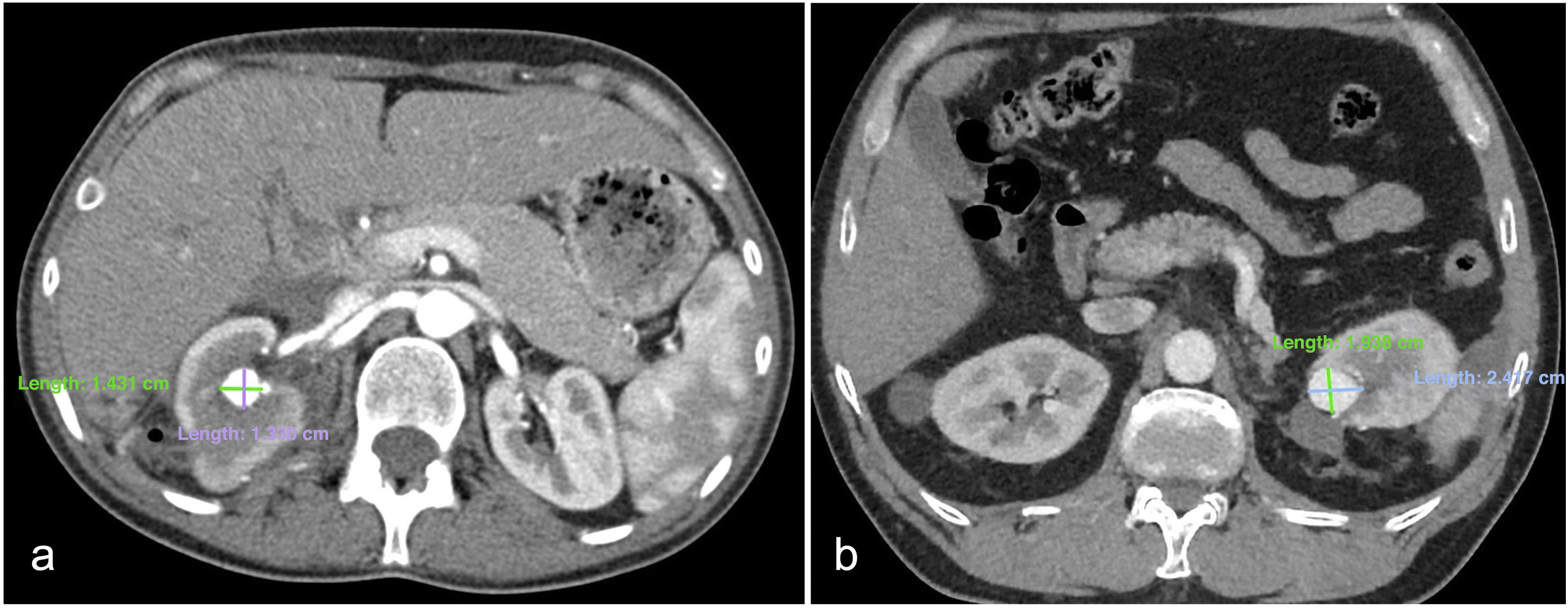

Vascular lesion size was measured on an axial image of the pre-procedural CCT scan in the arterial phase, and the areas (mm²) were calculated using the ellipse area formula (A = πab, where ‘a’ represents the semi-major axis and ‘b’ the semi-minor axis), as shown in Fig. 2.

Axial images in arterial phase of CCT showing a PSA + AVF (a) in the middle third of the right kidney following NSS and a PSA (b) in the upper pole of the left kidney following NSS. The major and minor axes of the lesions are 14 and 13 mm in (a), and 24 and 19 mm in (b), respectively. The lesion areas calculated using the ellipse formula are 143 mm2 in (a) and 358 mm2 in (b).

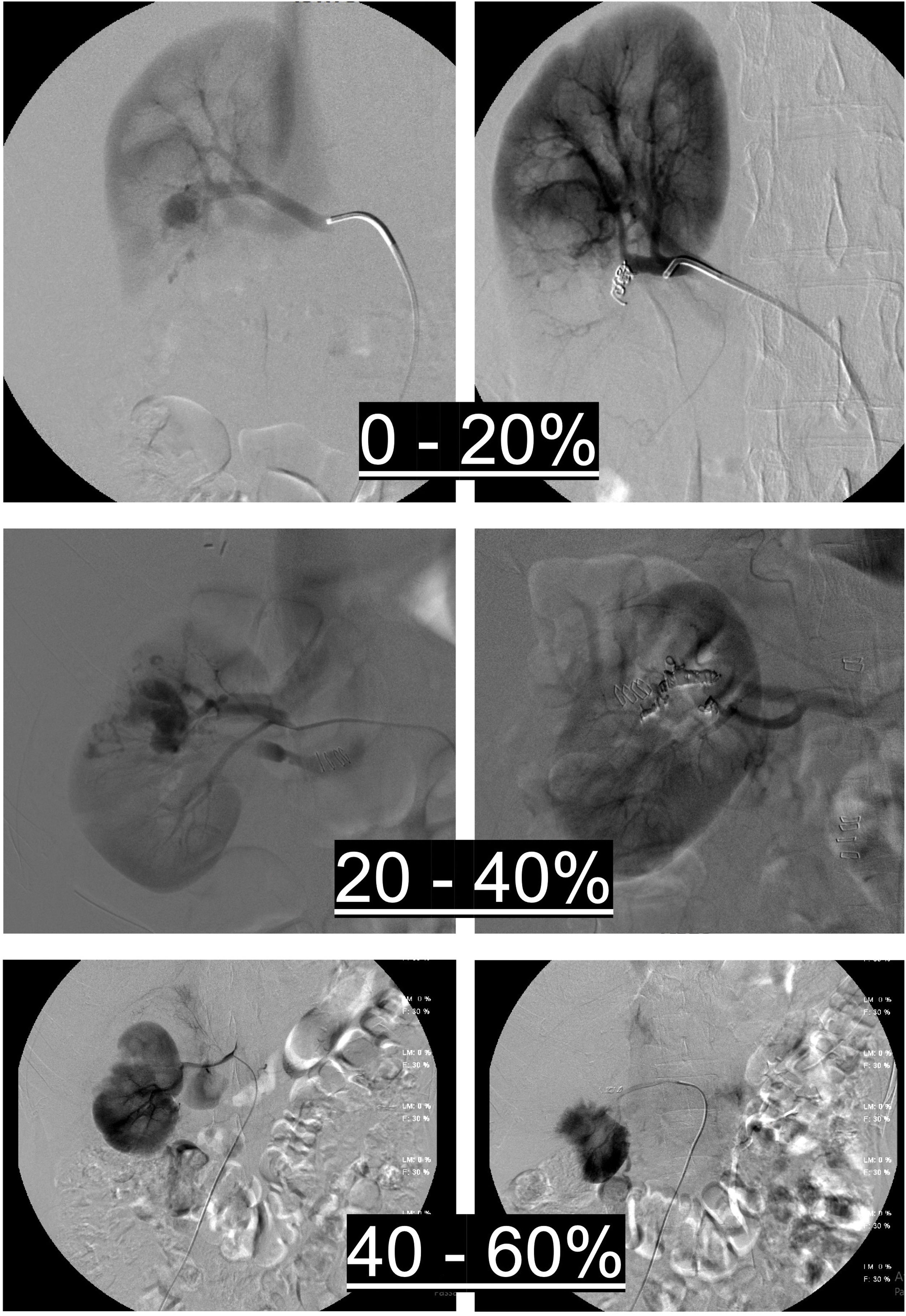

Renal parenchymal loss was calculated by comparing the first and last renal parenchymal scans and assessing the percentage (%) of ischaemic renal parenchyma, with stratification of the area of ischaemia into 0–20%, 20–40%, 40–60% and >60%, which was also divided into 0–20% and 20–60% for statistical analysis. Fig. 3 explains how ischaemic renal parenchyma was assessed after TAE.

Assessment of renal parenchymal ischaemia after the procedure by comparing pre- and post-TAE renal parenchymal imaging, with stratification of the area of ischaemia into 0–20%, 20–40% and 40–60% based on the amount of unenhanced renal parenchyma after TAE compared to pre-TAE parenchymal imaging.

All cases were followed up with regular clinical examinations and laboratory tests (serum creatinine and eGFR). Patients were constantly monitored immediately after TAE to check for improvement in both clinical and laboratory findings, in particular to confirm that cardiocirculatory parameters (heart rate and blood pressure) and haemoglobin levels had returned to normal physiological values and to confirm the cessation of haematuria. In cases where clinical data indicated persistent bleeding, a new abdominal CCT was obtained and, if a PSA or a PSA + AVF was still present, a new TAE was performed.

After the first four-stage CT scan, no further imaging was performed to avoid the risk of renal function deterioration as a consequence of the iodinated contrast medium. No isotopic renograms were performed due to their limited availability in our centres.

Patients received medium- and long-term clinical or radiological follow-up according to a schedule tailored to their specific underlying condition, such as cancer, kidney stones, or hydroureteronephrosis.

Statistical methodsAll data were analysed using SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The paired Student's t-test was used to compare eGFR values.

The correlation between the vascular lesion area and eGFR values was expressed using the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

The effect of the lesion size (area) on the area of ischaemia was evaluated using a univariate logistic regression method and expressed as an odds ratio (OR).

The Student's t-test with independent samples was used to compare eGFR values between categories of ischaemia area (0–20%/20–60%) and vascular lesion type.

Lesion areas were compared according to vascular lesion type using the Mann–Whitney U test.

The association between the vascular lesion type and the area of ischaemia was analysed with the Fischer's exact test.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

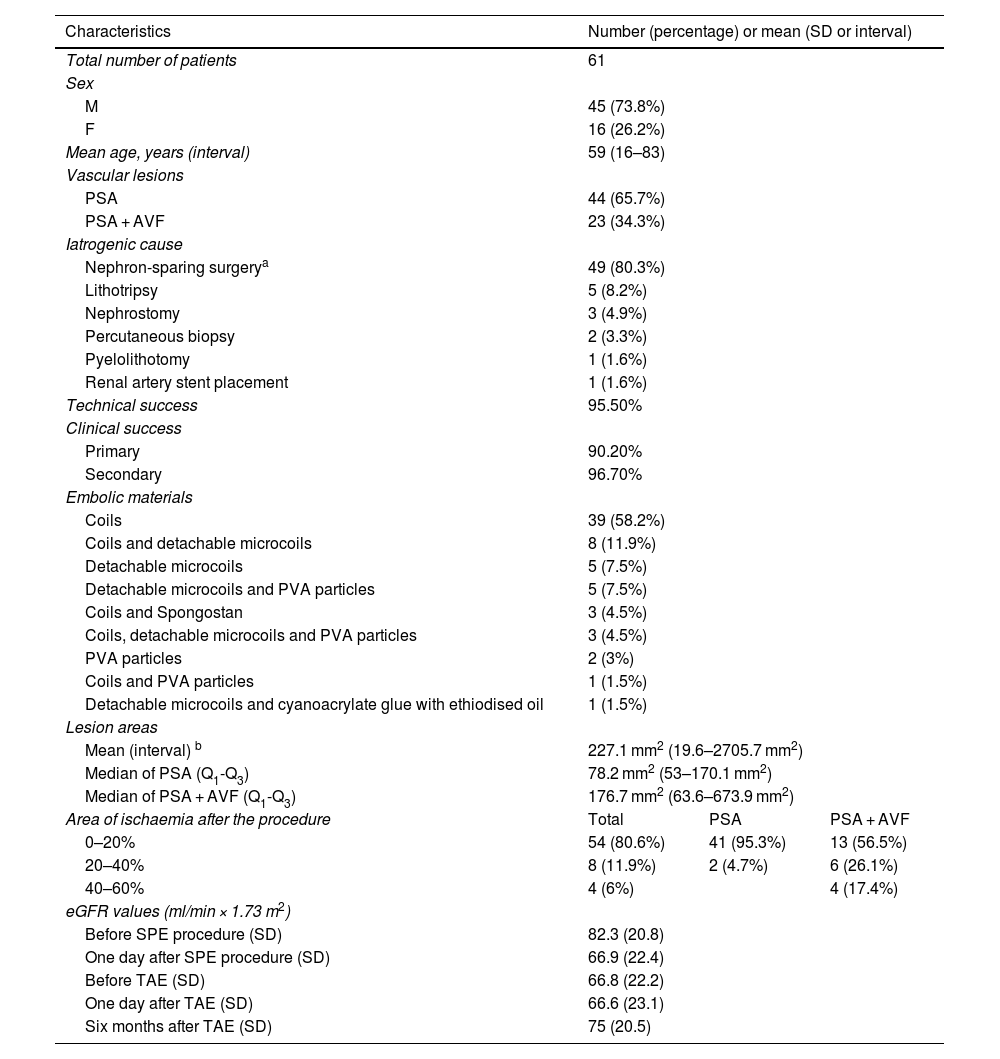

ResultsSixty-seven embolisation procedures were performed in 61 consecutive patients. Table 1 shows the demographic, clinical and angiographic data.

Demographic, clinical and angiographic data.

| Characteristics | Number (percentage) or mean (SD or interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 61 | ||

| Sex | |||

| M | 45 (73.8%) | ||

| F | 16 (26.2%) | ||

| Mean age, years (interval) | 59 (16–83) | ||

| Vascular lesions | |||

| PSA | 44 (65.7%) | ||

| PSA + AVF | 23 (34.3%) | ||

| Iatrogenic cause | |||

| Nephron-sparing surgerya | 49 (80.3%) | ||

| Lithotripsy | 5 (8.2%) | ||

| Nephrostomy | 3 (4.9%) | ||

| Percutaneous biopsy | 2 (3.3%) | ||

| Pyelolithotomy | 1 (1.6%) | ||

| Renal artery stent placement | 1 (1.6%) | ||

| Technical success | 95.50% | ||

| Clinical success | |||

| Primary | 90.20% | ||

| Secondary | 96.70% | ||

| Embolic materials | |||

| Coils | 39 (58.2%) | ||

| Coils and detachable microcoils | 8 (11.9%) | ||

| Detachable microcoils | 5 (7.5%) | ||

| Detachable microcoils and PVA particles | 5 (7.5%) | ||

| Coils and Spongostan | 3 (4.5%) | ||

| Coils, detachable microcoils and PVA particles | 3 (4.5%) | ||

| PVA particles | 2 (3%) | ||

| Coils and PVA particles | 1 (1.5%) | ||

| Detachable microcoils and cyanoacrylate glue with ethiodised oil | 1 (1.5%) | ||

| Lesion areas | |||

| Mean (interval) b | 227.1 mm2 (19.6–2705.7 mm2) | ||

| Median of PSA (Q1-Q3) | 78.2 mm2 (53–170.1 mm2) | ||

| Median of PSA + AVF (Q1-Q3) | 176.7 mm2 (63.6–673.9 mm2) | ||

| Area of ischaemia after the procedure | Total | PSA | PSA + AVF |

| 0–20% | 54 (80.6%) | 41 (95.3%) | 13 (56.5%) |

| 20–40% | 8 (11.9%) | 2 (4.7%) | 6 (26.1%) |

| 40–60% | 4 (6%) | 4 (17.4%) | |

| eGFR values (ml/min × 1.73 m2) | |||

| Before SPE procedure (SD) | 82.3 (20.8) | ||

| One day after SPE procedure (SD) | 66.9 (22.4) | ||

| Before TAE (SD) | 66.8 (22.2) | ||

| One day after TAE (SD) | 66.6 (23.1) | ||

| Six months after TAE (SD) | 75 (20.5) | ||

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; F: female; M: male; PSA: pseudoaneurysm; PSA + AVF: pseudoaneurysm with arteriovenous fistula; PVA: polyvinyl alcohol; Q1: lower quartile; Q3: upper quartile; SD: standard deviation; SPE: surgical, percutaneous or endoscopic; TAE: transarterial embolisation.

We identified 44 iatrogenic PSAs and 23 iatrogenic PSAs + AVF; four patients had two PSAs at the same time and two patients had a PSA and a PSA + AVF at the same time.

Table 1 lists the causes of iatrogenic vascular lesions, the embolic materials, the mean area of the vascular lesions and the percentage of ischaemic renal parenchyma after the procedure.

Technical success was achieved in 64 procedures (95.5%). In two cases, only partial embolisation was possible, but the bleeding stopped spontaneously and a follow-up CCT one week later did not document extravasation of the contrast medium. In one case the procedure had to be suspended due to technical problems (power failure) and the patient had to be transferred to a nearby interventional radiology department, where the procedure was successfully completed. Therefore, there was a technical failure rate of 4.5% which involved three of the 67 procedures.

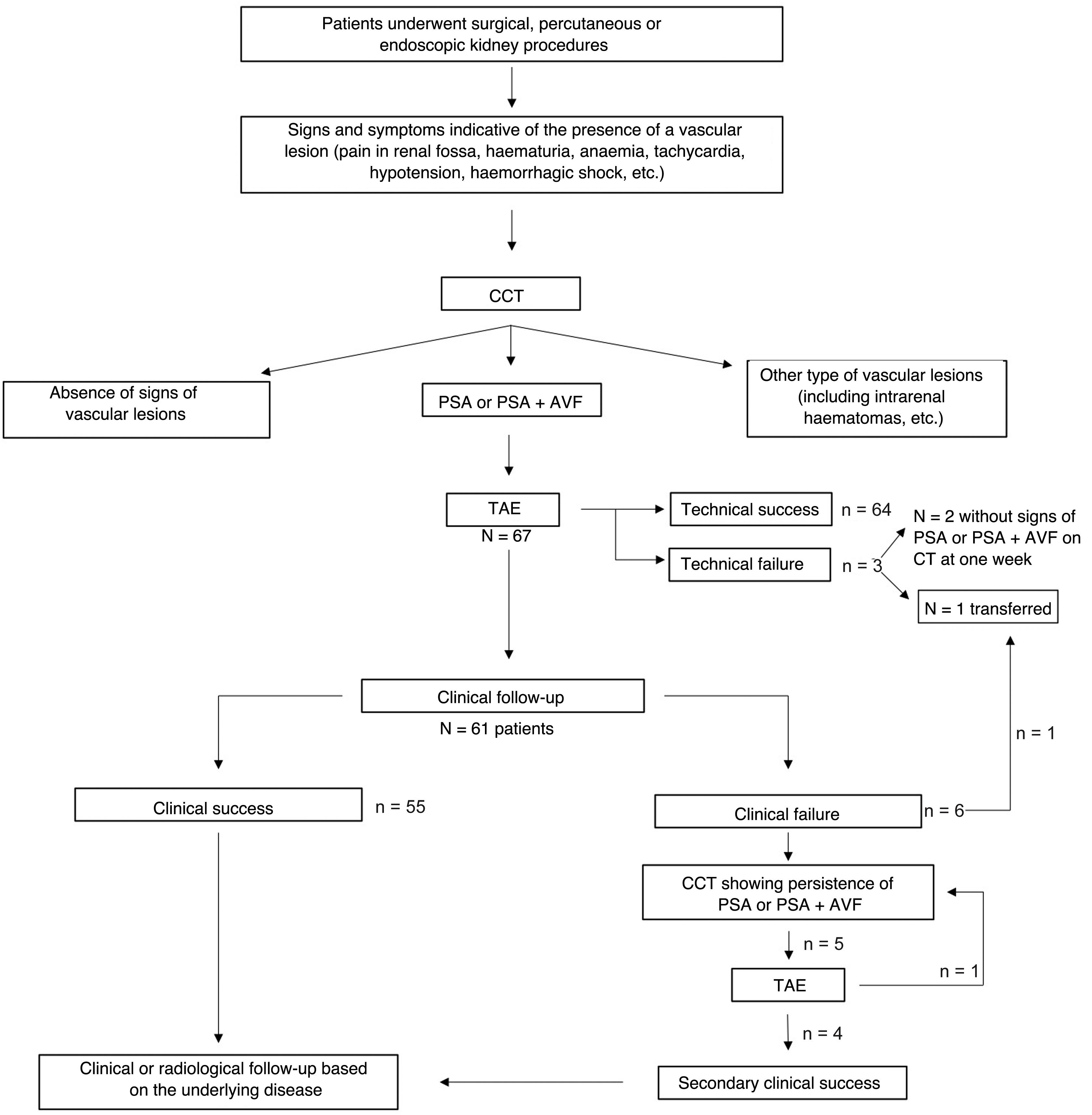

Clinical success was initially obtained in 55 patients (90.2%). Five patients presented haemorrhagic symptoms at two, six, four, eight and seven days after the first embolisation procedure. One CCT scan indicated persistent PSA or PSA + AVF, leading to another embolisation procedure which achieved final haemostasis (secondary clinical success, 59/61, 96.7%). In only one case it was necessary to carry out a third embolisation two days after the second procedure.

Technical and clinical successes and failures are shown in the flow chart (Fig. 4).

No complications were observed.

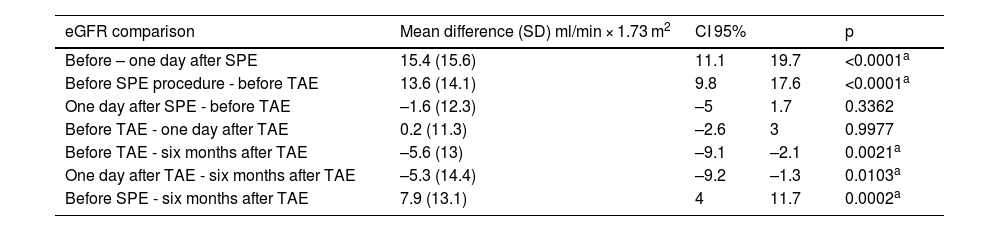

The mean values of eGFR and the mean differences of these values are shown in Tables 1 and 2 and in Fig. 5. The eGFR values prior to and after the SPE procedure were available for 53 patients. The eGFR values prior to and one day after the TAE were available for all patients with one exception. The eGFR values at six months were available for 48 patients because contact was lost during the follow-up stage with six patients and the procedure was carried out six months before the study in another six patients. There was a significant decrease in eGFR one day after the SPE procedure. No significant differences were observed in renal function prior to and one day after the TAE. The difference between the eGFR values prior to the TAE and at six months was statistically significant, with a minimal but significant improvement in renal function at six months (mean difference in eGFR 5.6 ml/min × 1.73 m2).

Mean differences in the eGFR values at different points in time. There was a significant decrease in the eGFR after the SPE procedures, but eGFR did not decrease after TAE. A minimal improvement in renal function was observed at the six-month follow-up.

| eGFR comparison | Mean difference (SD) ml/min × 1.73 m2 | CI 95% | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before – one day after SPE | 15.4 (15.6) | 11.1 | 19.7 | <0.0001a |

| Before SPE procedure - before TAE | 13.6 (14.1) | 9.8 | 17.6 | <0.0001a |

| One day after SPE - before TAE | –1.6 (12.3) | –5 | 1.7 | 0.3362 |

| Before TAE - one day after TAE | 0.2 (11.3) | –2.6 | 3 | 0.9977 |

| Before TAE - six months after TAE | –5.6 (13) | –9.1 | –2.1 | 0.0021a |

| One day after TAE - six months after TAE | –5.3 (14.4) | –9.2 | –1.3 | 0.0103a |

| Before SPE - six months after TAE | 7.9 (13.1) | 4 | 11.7 | 0.0002a |

CI 95%: confidence interval of 95%; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; PSA: pseudoaneurysm; SD: standard deviation; SPE: surgical, percutaneous or endoscopic; TAE: transarterial embolisation.

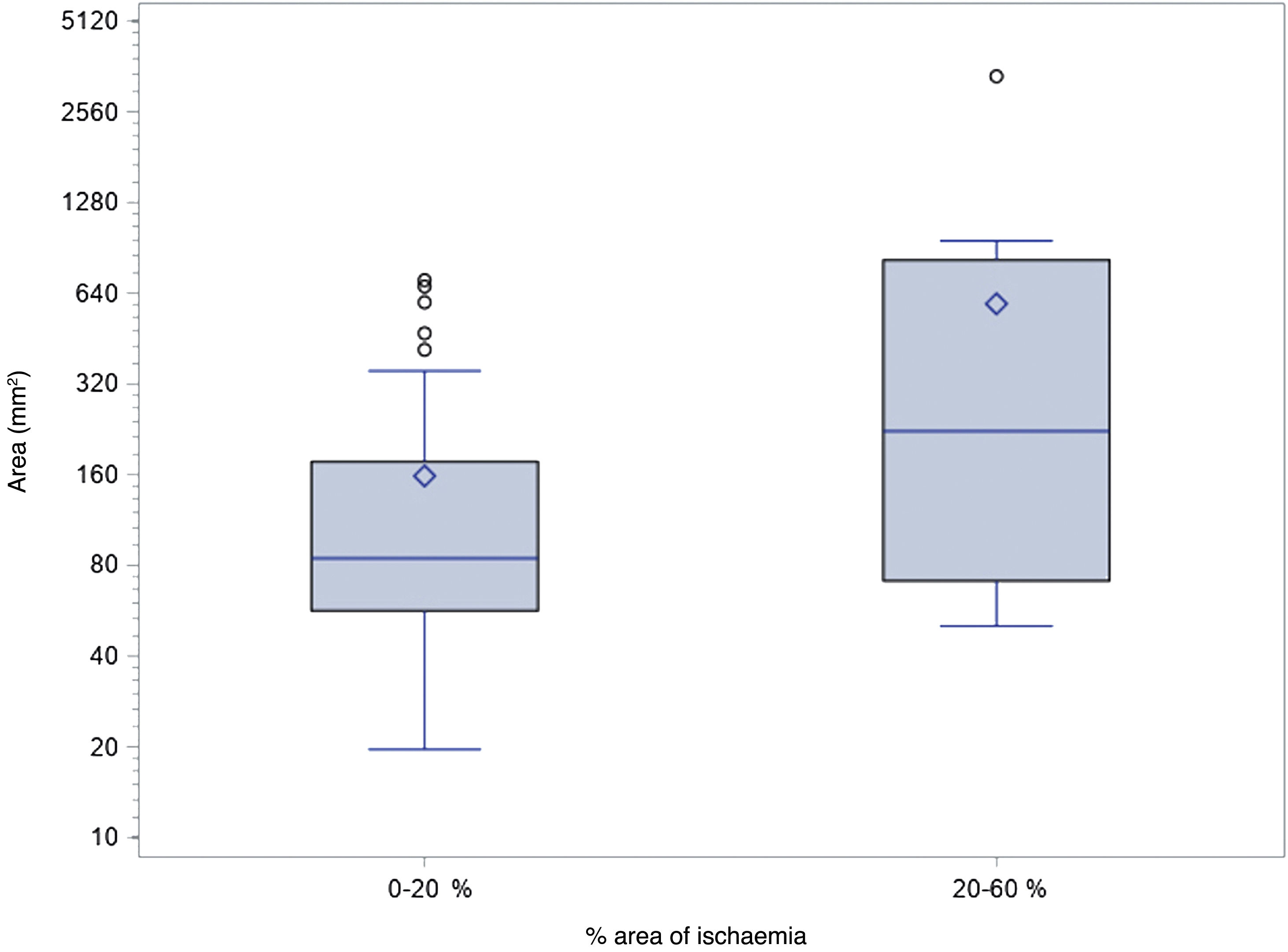

The probability of a 20–60% area of renal ischaemia after the procedure was multiplied by a factor of 1.8 for every 200 mm2 of vascular lesion area (Fig. 6).

Correlation between the areas of vascular lesion (mm2) and the percentage of ischaemic renal parenchyma after the procedure (%). The probability of a 20–60% area of renal ischaemia after the procedure was multiplied by a factor of 1.8 for every 200 mm2 of vascular lesion area (OR: 1.845; CI 95%: 1.16–3.25; p = 0.0219).

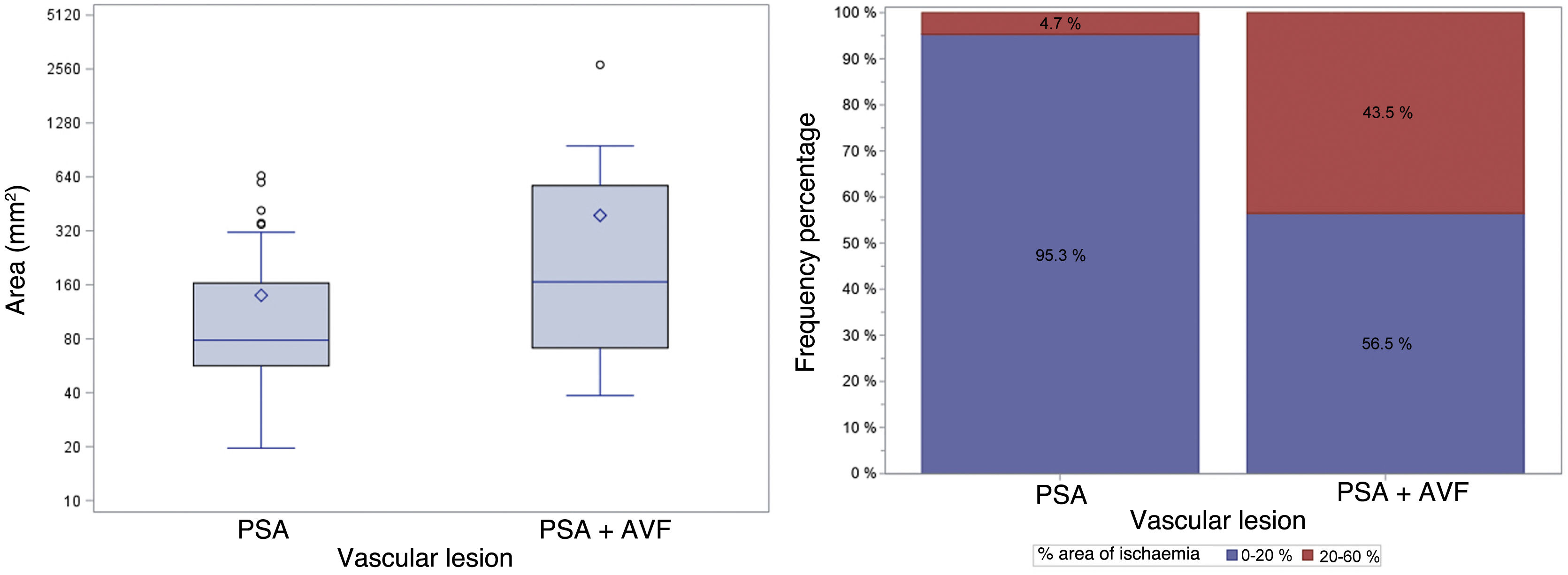

Fig. 7 shows the differences between PSA areas and PSA + AVF areas and the probability of having an area of ischaemia of 20–60% after the procedure.

On the left, areas (mm2) of vascular lesions in relation to the type of vascular lesion. The areas of PSAs + AVF were significantly greater than the PSA sizes (median of the difference 78.15 mm2; CI 95%: 8.6 mm2–201.1 mm2; p = 0.0142). On the right, the frequency of ischaemic areas after the procedure, classified as 0–20% or 20–60%, based on the type of vascular lesion. The probability of having an ischaemic area of 20–60% after the procedure was significantly higher in the PSA + AVF group (difference in proportions 38.8%; CI 95%: 16.4%–61.5%; p = 0.0002).

CI 95%: confidence interval of 95%; PSA: pseudoaneurysm; PSA + AVF: pseudoaneurysm with arteriovenous fistula.

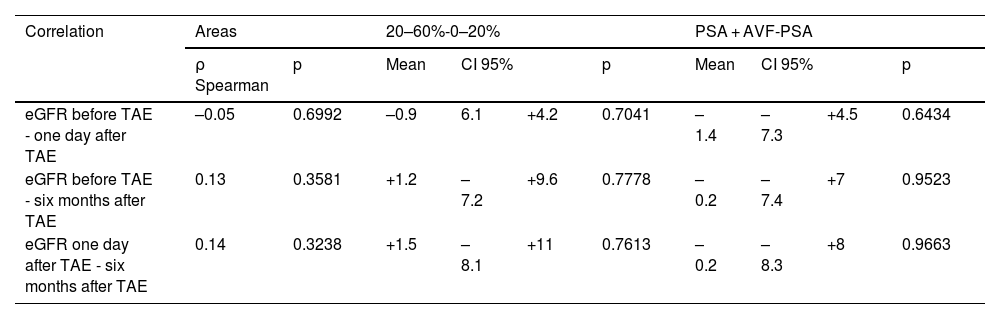

No correlation was observed between the vascular lesion area, the percentage of ischaemic renal parenchyma after the procedure, the type of vascular lesion, and the difference in eGFR values before and after the procedure (Table 3).

Correlation between the different mean values of eGFR at different points in time and the vascular lesion sizes (expressed using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient), the percentage of ischaemic renal parenchyma after the procedure and the type of vascular lesion. eGFR is measured in ml/min × 1.73 m2. No significant correlations were observed.

| Correlation | Areas | 20–60%-0–20% | PSA + AVF-PSA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ Spearman | p | Mean | CI 95% | p | Mean | CI 95% | p | |||

| eGFR before TAE - one day after TAE | –0.05 | 0.6992 | –0.9 | 6.1 | +4.2 | 0.7041 | –1.4 | –7.3 | +4.5 | 0.6434 |

| eGFR before TAE - six months after TAE | 0.13 | 0.3581 | +1.2 | –7.2 | +9.6 | 0.7778 | –0.2 | –7.4 | +7 | 0.9523 |

| eGFR one day after TAE - six months after TAE | 0.14 | 0.3238 | +1.5 | –8.1 | +11 | 0.7613 | –0.2 | –8.3 | +8 | 0.9663 |

CI 95%: confidence interval of 95%; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; PSA: pseudoaneurysm; PSA + AVF: pseudoaneurysm with arteriovenous fistula; TAE: transarterial embolisation.

Iatrogenic PSAs and PSAs + AVF are becoming increasingly common in everyday clinical practice.9

NSS was the principal cause in our series (49/61). Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (PN) has been linked to a higher incidence of PSA compared to open PN, whereas data on robot-assisted PN remain limited and sporadic.2,21 An incidence of 0.5% renal PSA has been reported after open PN and 1.7% after laparoscopic PN, although the actual incidence of PSA and PSA + AVF following robot-assisted PN remains inconclusive.4,12,22–24 Several authors have suggested that longer surgery times, prolonged cold ischaemia time and tumour proximity to the renal sinus or collecting system may account for the higher incidence of PSA and PSA + AVF.13,25

The onset of PSAs and PSAs + AVF after surgery can occur anywhere from hours to months, with most cases presenting within 15 days. It is important to rule out the presence of PSAs and PSAs + AVF in patients with typical symptoms even months after surgical intervention.14,26,27

Other causes of PSAs and PSA + AVFs in our series include nephrolithotomies, nephrostomies, and renal biopsies, with reported incidences of 0.4–0.7%, 2%, and 5%, respectively. Angioplasties, stent placement, lithotripsies, and other endourological procedures are extremely rare causes.9,28

TAE is considered the best treatment option for symptomatic PSAs or PSAs + AVF. The first reported case dates back to 1975.29 The preferred embolic agents are microcoils, which allow selective and distal embolisation in order to preserve maximal vascularisation and minimise renal parenchymal loss. It should be noted that embolic materials such as PVA particles cannot be used for PSAs + AVF due to the risk of migration of the material into the venous system. However, PVA particles can be safely used to completely occlude the segment of a target artery, especially in cases of small, distal PSAs (no venous communication). If superselective positioning of the microcatheter in the target vessel is not possible, PVA particles can be injected followed by one or more coils. Coil embolisation is very effective and induces complete vessel closure and exclusion of the target vascular lesion. Glue is reserved for severe arterial lesions, as it allows for rapid closure, but must be administered with caution to avoid backflow into non-targeted branches.15,16 We used cyanoacrylate glue with ethiodised oil in one patient during their third embolisation procedure, after coils, detachable coils and PVA particles proved ineffective. The choice of embolic agent and the combination used is based on the diameter of the target vessel, the presence or absence of an AVF and the experience of the interventional radiologist.

TAE is safe and highly effective, achieving up to 100% technical and clinical success in most published studies. Our findings align closely with the results of previous research.1,7,11,13–16,24

A clinical success rate of 90.2% was obtained, with five patients having to undergo a second embolisation due to a reperfusion of the pseudoaneurysmal sac, a complication documented in the medical literature.13,15,24 The need for a second intervention is related to various factors, such as incomplete embolisation, accessory vessels, recanalisation of treated vessels or the formation of new pseudoaneurysms.17

A highly debated topic is the timing of PSA treatment. Aside from symptomatic cases, not all renal artery PSAs require treatment. Worsening anaemia and large pseudoaneurysmal sacs require intervention because of the risk of massive haemorrhage.4,13,27,30

Embolisation of a renal artery branch supplying a PSA or a PSA + AVF inevitably generates an area of parenchymal ischaemia even if the embolisation is performed as distally as possible, since renal artery branches are anatomically terminal arteries. As established, the volumetric method using CCT imaging is the gold standard for assessing the volume of renal parenchyma loss following an embolisation procedure. However, this approach requires both pre- and post-procedural CCT scans. To calculate the percentage of renal parenchymal ischaemia, we decided to assess the first and last renal parenchyma images, given that angiographic images were available for all patients. CT images, which would have allowed for a more reliable volumetric assessment, were unavailable for many patients due to various reasons. Primarily, patients were often referred to our interventional radiology centres for the embolisation procedure or for follow-up surgical/urological investigations, and the radiological scans had been performed at other centres. This study shows that the percentage of sacrificed parenchyma depends on both the size and type of vascular lesion. We demonstrated that for every 200 mm² increase in the size of the vascular lesion, the likelihood of a larger ischaemic area (20–60%) resulting from the embolisation procedure increased by a factor of 1.8. We also observed that PSA + AVF lesions are significantly larger than PSAs, and their embolisation leads to a larger ischaemic area. Although we had investigated this in our earlier study, the results were not definitive.18 Another possible explanation for the larger ischaemic area produced by PSA + AVF lesions could be the proximal location of the communication between the renal arterial and venous branches, which would require a more proximal embolisation. To our knowledge, there are no data in the medical literature recommending one embolic material or another to reduce the area of ischaemia after the procedure. However, Dong et al.31 suggest that embolisation in as distal a position as possible with microcoils allows for minimal parenchymal loss, compared to the use of gelatin sponge or PVA particles followed by coils when superselective embolisation is not possible. In these cases, the use of particles with coils may be effective in occluding the vascular lesion, but may result in a larger area of ischaemia after the procedure.

As a result of renal parenchyma loss, the hypothesis of reduced renal function should at least be considered. Contact was lost with six patients during follow-up, and their eGFR values at six months were not available. This may be due to the retrospective nature of the study and the fact that the centres included are referral centres for interventional radiology. Another six patients had undergone the procedure in the six months prior to the study and their eGFR values were not available. However, they were included in the study for the purpose of assessing the area of post-procedural ischaemia, as these data were available from the TAE angiographic images. eGFR values at six months after TAE were significantly lower than the eGFR values before the ‘causative’ procedure, but the significant decline in renal function occurred after the SPE procedures. No worsening of renal function was observed before and after TAE or before TAE and at six months, when eGFR values showed a very small but statistically significant improvement compared to pre-TAE values. No negative effect on renal function was observed in either group. It should be noted that larger lesions and PSAs + AVF, which resulted in larger areas of ischaemia, did not lead to reduced renal function. This study demonstrates that although TAE results in some parenchymal loss, it does not adversely affect renal function. This could be explained by homeostatic compensatory mechanisms, including hypertrophy of the preserved renal parenchyma. Previous studies have investigated the effect of TAE on renal function. Although their results align with those of our study, they primarily focused on creatinine levels or eGFR immediately post-TAE, without medium- or long-term follow-up. Additionally, many studies had smaller sample sizes or only considered PSAs or PSAs + AVF after NSS, excluding other procedures.6,7,11–18 Chavali et al.13 reviewed 1,417 cases of PN, 20 of which developed PSA and underwent TAE. The authors found no differences in the preservation of eGFR when comparing the embolisation patients with the controls. Gupta et al.17 observed no long-term adverse effects on renal function when comparing the eGFR values of 25 patients before and after TAE, except in the case of one patient with a solitary kidney. Our findings contrast with those reported by Lee et al.,25 and this is likely due both to our larger sample size and the fact that they also took into account renal function at one year, which may be affected not only by TAE but also by chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension or an age-related reduction in eGFR. Other studies have used dynamic radioisotope renography to assess renal function after TAE, and their results are consistent with those of our study, which is based on eGFR calculated using the CKD-EPI formula.32,33

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to investigate the relationship between vascular lesion size and type as well as the area of ischaemia after TAE in a homogeneous sample. Secondly, this study uses a larger sample than most published studies to reveal that TAE preserves renal function when used to treat iatrogenic PSAs and PSAs + AVF. Finally, our study confirms the technical and clinical efficacy of TAE for iatrogenic renovascular lesions.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective design and the lack of comparison with a cohort of patients treated surgically. However, the relatively low incidence of these vascular lesions makes a prospective randomised trial unlikely. Patients are also unlikely to undergo surgery as a first-line treatment. Furthermore, this study does not correlate renal parenchymal preservation with quantitative and qualitative tests of renal function.

Further studies are needed to review the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the treatment of PSAs and PSAs + AVF, as well as to investigate the causes of reperfusion of the pseudoaneurysmal sac.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, TAE is the treatment of choice for PSAs and PSAs + AVF, as it is safe, effective, and associated with high technical and clinical success rates. TAE does not significantly reduce renal function, regardless of the size and type of vascular lesion or the area of ischaemia after the procedure.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors contributed to the study concept and design. Dr. Stefano Groff, Dr. Giulio Barbiero and Prof. Anna Chiara Frigo prepared the material, data collection and analysis. Dr. Stefano Groff and Dr. Giulio Barbiero wrote the first draft of the article, and all authors gave their opinions on previous versions. All authors read and approved the final version.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all individuals who participated in the study.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grants from funding bodies in the public, private or non-profit sectors.