The sense of taste is fundamental to life; some studies have revealed a link between dental deafferentation (DD) by upper molar extraction and taste abnormalities in rats. However, no studies have been found that evaluate these variables using the Taste Reactivity Test (TRT).

MethodsForty male Wistar rats (20 juveniles and 20 adults) were used and assigned to a control and experimental group. Both groups were fitted with cannulae for TRT, while rats in the experimental group also had their right upper molars extracted. Using an ingestive solution (1 M sucrose) and an aversive solution (3 mM denatonium benzoate [BD]), TRT was performed on days 1, 7, 14, and 21. Body and orofacial reactions were recorded and scored.

ResultsDD influences ingestive responses in juvenile rats at days 7, 14, and 21; however, it only affects aversive responses at day 21. In adult rats, it influences ingestive responses at days 14 and 21, although it only affects aversive responses at day 14. When comparing ingestive and aversive responses between juvenile and adult rats in the experimental group, differences were identified in ingestive responses at days 7 and 14.

ConclusionsIn juvenile and adult rats, upper molar extraction has a negative influence on ingestive and aversive responses. In addition, compared to adult rats, it has a negative effect on ingestive responses in juvenile rats.

El sentido del gusto es fundamental para la vida, algunos estudios han revelado un vínculo entre la desaferentación dental (DD) mediante exodoncia de molares superiores en ratas y anomalías del gusto. Sin embargo, no se han encontrado trabajos que evalúen estas variables mediante el test de reactividad gustativa (TRG).

MétodosSe utilizaron 40 ratas Wistar machos, 20 jóvenes y 20 adultos, en cada categoría asignadas a un grupo control y experimental. A ambos grupos se les colocaron cánulas para TRG, mientras que a las ratas del grupo experimental se les extrajo los molares superiores derechos. Utilizando una solución ingestiva (sacarosa 1 M) y una aversiva (benzoato de denatonio [BD] 3 mM), se realizó el TRG los días 1, 7, 14 y 21. Se registraron y calificaron las reacciones corporales y orofaciales.

ResultadosLa DD influye en las respuestas ingestivas en ratas jóvenes a los 7, 14 y 21 días; en cambio solo afecta las respuestas aversivas el día 21. En ratas adultas influye en las respuestas ingestivas a los 14 y 21 días; aunque solo afecta las respuestas aversivas el día 14. Al contrastar las respuestas ingestivas y aversivas entre ratas jóvenes y adultos de los grupos experimentales se identificó diferencias en las respuestas ingestivas los días 7 y 14.

ConclusionesEn ratas jóvenes y adultas, la DD tiene una influencia negativa sobre las respuestas ingestivas y aversivas. Además, en comparación con las ratas adultas, tiene un efecto negativo sobre las respuestas ingestivas de las ratas jóvenes.

Taste is the sense produced when chemical substances stimulate chemoreceptors of the gustatory papillae (GP) on the tongue, oropharynx, and larynx, which send information to a specific region of the brainstem (rostral part of the nucleus of the solitary tract [rNST], the first processing centre for gustatory information) via the facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves.1 In contrast, the concept of “flavour” involves taste, smell, and somatosensory information from the trigeminal nerve; therefore, the sense of taste contributes to the perception of flavour as a multimodal sensation involving intermodal interactions including taste/aroma.1,2

A range of factors may influence the way in which taste is perceived, including age, perioral and oral alterations, cancer, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, exposure to toxic chemical substances, trigeminal nerve lesions, drug use, etc.3–5

Elimination of trigeminal afferents is reported to affect electrogustometry thresholds.6 However, only one study has found an association between gustatory dysfunction and dental deafferentation (DD) due to tooth loss.7 That study determined that electrogustometry thresholds increased in line with the number of teeth with DD. Although oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures, and particularly wisdom tooth extraction, may cause gustatory alterations secondary to surgical damage to fibres of the lingual nerve,8 gustatory deficits caused by dental treatments9 or other types of DD, such as removal of other teeth (upper molars, incisors, etc) or root canal treatments cannot be explained by damage to the chorda tympani (CT) or glossopharyngeal nerve.7,10 Similarly, studies in rats have used histomorphometric analysis to determine the effect of DD on the GP, with extraction of the upper molars or placement of bite plates; animals showed significant morphological and structural alterations.11–13

To measure food liking in the absence of wanting, Grill and Norgren14,15 created the Taste Reactivity Test (TRT), which measures orofacial and bodily responses provoked by an appetitive or aversive gustatory stimulus in rodents; these responses can also be observed in humans and other animals. The test is most frequently applied in conditioned taste aversion paradigms,16,17 as well as research into gustatory palatability,18,19 satiety,20,21 sodium depletion,22,23 and learning and memory24,25; however, no study to date has used the TRT to evaluate the effect of DD. The hedonic pattern (ingestive responses) includes medial and lateral tongue protrusions and rhythmic mouth movements. On the contrary, the aversive patterns of responses include a triangular-shaped mouth opening (gaping), forward movement of the forelimbs (paw pushing), rubbing of the chin on the floor, head shaking, and face washing with both forelimbs.14,15

As people age, they experience changes in the intensity of different bitter stimuli, followed by changes in some sour, salty, and sweet stimuli.26 Missing teeth and poor oral hygiene are factors that may increase the gustatory threshold in older adults. Patients with full upper and lower dentures or with fewer than 7 teeth have been shown to present higher thresholds than individuals with more than 7 teeth.7,27 These results have been replicated in juvenile and senile rodents; for instance, Inui-Yamamoto et al.28 report that senile rats had a significantly lower preference for umami, sucrose, and quinine.

Based on the hypothesis that DD has a negative effect on the sense of taste in juvenile and adult albino rats, this study aims to determine how DD influences the sense of taste in juvenile and adult Wistar rats.

Materials and methodsAnimalsThis article reports an experimental study, conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE 2.0 principles (Animal Research Reporting of In Vivo Experiments); it used 40 male Wistar rats obtained from the vivarium of the faculty of medicine of Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia. Rats were kept in individual cages measuring 35 × 23 × 18 cm. They had ad libitum access to food pellets and water. They were kept under ideal conditions during testing: 12-h day-night cycle, 60–70% relative humidity, and a constant temperature of 22 °C.

Instruments- •

Mirrored chamber for the taste reactivity test. The TRT was performed in a trapezoidal mirrored chamber (similar to that used by Suarez,29 but individual), measuring 36 cm wide at the front and 14 cm at the rear, 30 cm tall, with side walls measuring 26 cm, with a trapezoidal lid measuring 42 cm wide at the front and 17 cm at the rear, with 29 cm sides and a 4 cm circular hole in the centre. The rear and side walls and the floor were made of mirrored glass. The front wall and lid were made of transparent glass.

- •

Infusion system for the taste reactivity test. Solutions were infused into the oral cavity using 7 cm of Clay Adams PE-50 polyethylene tubing (BD INTRAMEDIC, USA), fitted with an acrylic stop prior to a flange created at the end using a hot instrument.

In each TRT session, a 1″ cut-down 23G needle was inserted into the cannula. The needle hub was then fitted to a DIS extension, which in turn was attached to a three-way stopcock with an extension tube. A 3 cc syringe was used to administer the solutions through this system.

General procedureThe 40 rats were distributed as follows: 20 juveniles (2–3 months old) and 20 adults (5–6 months old). Within each age category, animals were randomly assigned to the control or to the experimental group (10 in each group). Both groups underwent bilateral cannula insertion for the TRT, under deep sedation with intraperitoneal injection of 40 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine. In the experimental group, we also extracted all 3 right upper molars. In the postoperative period, antibiotic and analgesic drugs were administered by intramuscular injection (penicillin–streptomycin 0.1 mg/kg and meloxicam 1 mg/kg), once daily for a maximum of 3 days.

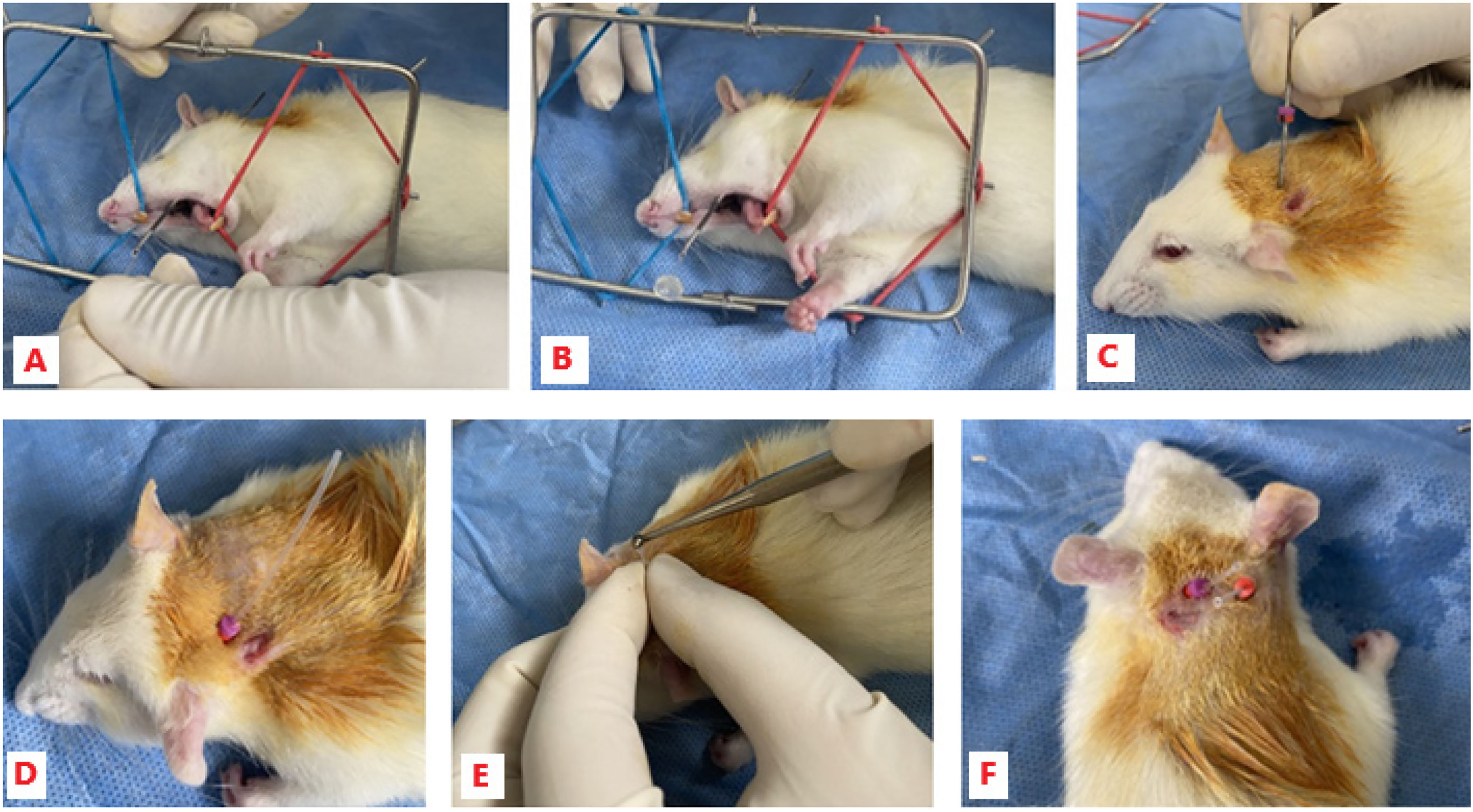

Implantation of cannulae for the taste reactivity testCannulae were implanted using a similar method to those described by Parker30,31 and by Clarke and Ossenkopp.32 First, the PE-50 cannula was fitted, with a flange created at one end using a hot instrument. An acrylic stop of 5 mm diameter was introduced from the other end and pushed up the cannula to the flange. The rats' necks were shaved at approximately 3 cm from the scapula, and aseptic and antiseptic treatment was performed with povidone-iodine foam and solution. The skin of the neck was subsequently perforated with a modified 3¼″ 18G epidural needle (without the plastic hub), which was passed through the subcutaneous cellular tissue to the oral cavity, at the level of the left upper molars. The prepared cannula was fed over the tip of the epidural needle emerging from the oral cavity; then, the needle was withdrawn and the cannula secured to the neck with 2 silicone endodontic stops. Finally, the non-oral end of the cannula was cut down to approximately 2 cm, a flange was made with a hot instrument, and the permeability of the line was tested by infusion of distilled water using a 1″ cut-down 23G needle (Fig. 1).

Implantation of cannulae for the taste reactivity test in male Wistar rats. (A and B) Placement of the prepared cannula over the tip of the modified epidural needle. (C and D) Placement of the endodontic stops to secure the cannula. (E) Creation of a flange on the cannula using a hot instrument. (F) Top view of the 2 implanted cannulae.

Teeth were extracted from animals in the experimental group using a similar method to that described by Hovsepian-Khatcherian et al.33 Syndesmotomy was performed with an endodontic explorer at the level of the right upper molars, with the cheeks separated using a modified cement spatula (active part bent at 90°). After teeth luxation, curved mosquito forceps were used to grip and pull the first, second, and third right upper molars. Haemostasis was achieved by using gauzes to compress the dental alveoli of the extracted upper molars.

Taste reactivity testOn the third day after cannula insertion, which coincided with the first day of the experimental period, TRT was started with intraoral infusion of an aversive solution (3 mM denatonium benzoate [DB]; Power Grown, USA) and an appetitive solution (1 M sucrose: Cuisine & Co granulated white sugar; Agro Industrial Paramonga S.A.A.) at 1 mL per minute. Testing was repeated on days 7, 14, and 21. A video camera was used to record ingestive and aversive responses during the one-minute infusion phase and the subsequent 30-s post-infusion phase (Fig. 2). Responses were quantified for 30 s of the infusion phase and 30 s of the post-infusion phase.

We studied the following ingestive responses: tongue protrusions, mouth movements, and paw licking. Gaping, head shaking, forelimb flailing, and expulsion of fluids were the aversive responses evaluated. Examples of the responses can be viewed at the following link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YIqAk89uDto.

Statistical analysisData were processed using the SPSS statistics software, version 26; normality of data distribution was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Data were analysed with the Mann–Whitney U test, as each group included fewer than 30 animals and not all variables were normally distributed.

We calculated the sum of ingestive and aversive responses in each rat, and the median of each type of response for a particular group of rats (juvenile or adult). Ingestive and aversive scores were evaluated independently, as they constitute phenomenologically distinct categories and because ingestive responses are shorter than aversive responses.34 Finally, we determined effect sizes by calculating the Rosenthal r, which is the most widely used statistic for non-parametric distributions.35 The analysis only accounted for ingestive responses to sucrose and aversive responses to DB, as the frequency of aversive responses to sucrose and ingestive responses to DB was negligible (nearly always zero).

The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate whether there were differences in ingestive and aversive responses in the TRT between juvenile and adult rats in the experimental and control groups. In comparison with significant results, the post hoc Games-Howell test was used to identify the differences. The threshold for significance was set at P < .05 for all analyses.

ResultsCharacteristics of the study populationOf the 20 juvenile Wistar rats, 2 rats from the control group died due to the anaesthesia; both cannulae were lost in one animal from the experimental group. Therefore, we analysed data from 8 rats in the control group and 9 rats in the experimental group. Among the adult rats, 2 animals in the control group died, whereas there were no deaths in the experimental group. Therefore, we analysed data from 8 rats in the control group and 10 rats in the experimental group.

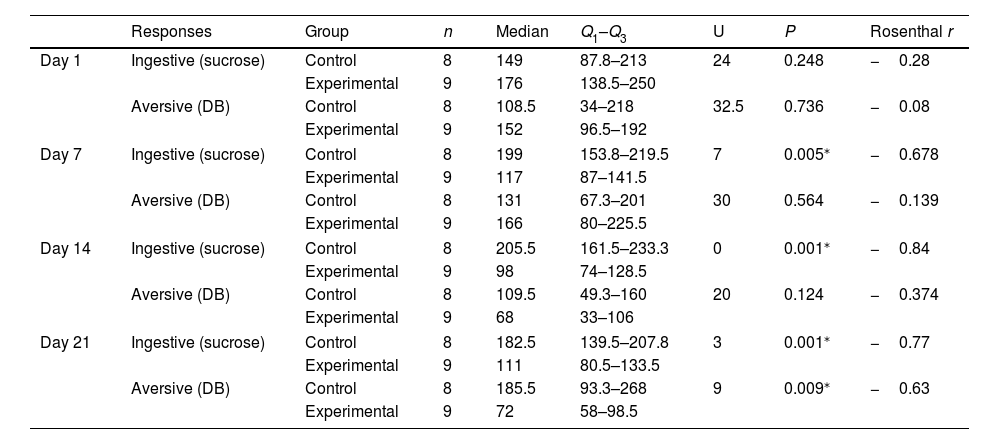

Taste reactivity test results in juvenile male Wistar ratsOn day 1, no significant differences were observed between groups in the number of ingestive responses to sucrose. However, we did observe significant differences on the remaining days of TRT sessions, with higher median scores in the control group than in the experimental group at days 7 (199 vs 117; P = .005; moderate effect size on the Cohen scale), 14 (205.5 vs 98; P = .001; large effect), and 21 (182.5 vs 111; P = .001; moderate effect). The number of aversive responses to DB showed no significant differences between the control and experimental groups at days 1, 7, or 14. However, we did observe a significant difference at day 21, with higher median scores in the control group (185.5 vs 72; P = .009; moderate effect) (Table 1).

Comparison of the number of responses in the taste reactivity test in juvenile Wistar rats at days 1, 7, 14, and 21 (Mann–Whitney U test).

| Responses | Group | n | Median | Q1–Q3 | U | P | Rosenthal r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Ingestive (sucrose) | Control | 8 | 149 | 87.8–213 | 24 | 0.248 | −0.28 |

| Experimental | 9 | 176 | 138.5–250 | |||||

| Aversive (DB) | Control | 8 | 108.5 | 34–218 | 32.5 | 0.736 | −0.08 | |

| Experimental | 9 | 152 | 96.5–192 | |||||

| Day 7 | Ingestive (sucrose) | Control | 8 | 199 | 153.8–219.5 | 7 | 0.005⁎ | −0.678 |

| Experimental | 9 | 117 | 87–141.5 | |||||

| Aversive (DB) | Control | 8 | 131 | 67.3–201 | 30 | 0.564 | −0.139 | |

| Experimental | 9 | 166 | 80–225.5 | |||||

| Day 14 | Ingestive (sucrose) | Control | 8 | 205.5 | 161.5–233.3 | 0 | 0.001⁎ | −0.84 |

| Experimental | 9 | 98 | 74–128.5 | |||||

| Aversive (DB) | Control | 8 | 109.5 | 49.3–160 | 20 | 0.124 | −0.374 | |

| Experimental | 9 | 68 | 33–106 | |||||

| Day 21 | Ingestive (sucrose) | Control | 8 | 182.5 | 139.5–207.8 | 3 | 0.001⁎ | −0.77 |

| Experimental | 9 | 111 | 80.5–133.5 | |||||

| Aversive (DB) | Control | 8 | 185.5 | 93.3–268 | 9 | 0.009⁎ | −0.63 | |

| Experimental | 9 | 72 | 58–98.5 | |||||

DB: denatonium benzoate; Q1–Q3: quartiles 1 and 3.

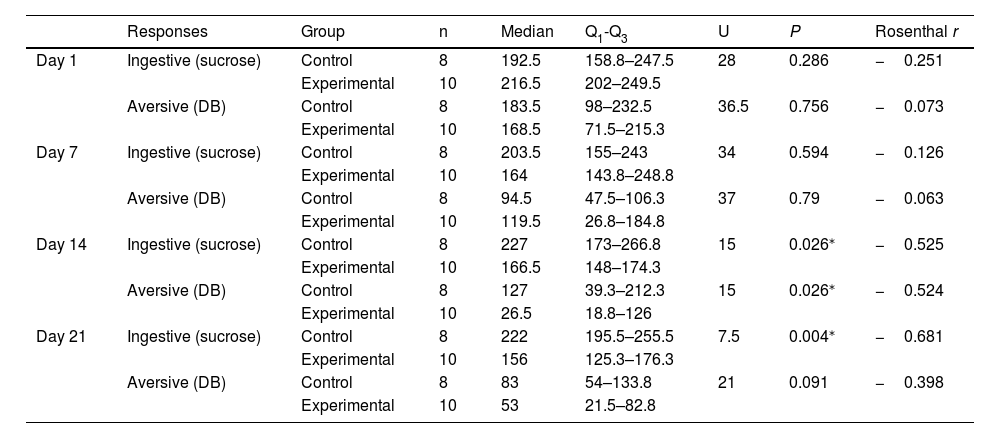

On days 1 and 7, no significant differences were observed between groups in the number of ingestive responses to sucrose. However, we did observe significant differences on days 14 and 21, with higher median scores in the control group (day 14: 227 vs 166.5; P = .026; moderate effect; day 21: 222 vs 156; P = .004; moderate effect). The number of aversive responses to DB showed no significant differences between the control and experimental groups at days 1, 7, or 21. However, we did observe a significant difference at day 14, with higher median scores in the control group (127 vs 26.5; P = .026; moderate effect) (Table 2).

Comparison of the number of responses in the taste reactivity test in adult Wistar rats at days 1, 7, 14, and 21 (Mann–Whitney U test).

| Responses | Group | n | Median | Q1-Q3 | U | P | Rosenthal r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Ingestive (sucrose) | Control | 8 | 192.5 | 158.8–247.5 | 28 | 0.286 | −0.251 |

| Experimental | 10 | 216.5 | 202–249.5 | |||||

| Aversive (DB) | Control | 8 | 183.5 | 98–232.5 | 36.5 | 0.756 | −0.073 | |

| Experimental | 10 | 168.5 | 71.5–215.3 | |||||

| Day 7 | Ingestive (sucrose) | Control | 8 | 203.5 | 155–243 | 34 | 0.594 | −0.126 |

| Experimental | 10 | 164 | 143.8–248.8 | |||||

| Aversive (DB) | Control | 8 | 94.5 | 47.5–106.3 | 37 | 0.79 | −0.063 | |

| Experimental | 10 | 119.5 | 26.8–184.8 | |||||

| Day 14 | Ingestive (sucrose) | Control | 8 | 227 | 173–266.8 | 15 | 0.026⁎ | −0.525 |

| Experimental | 10 | 166.5 | 148–174.3 | |||||

| Aversive (DB) | Control | 8 | 127 | 39.3–212.3 | 15 | 0.026⁎ | −0.524 | |

| Experimental | 10 | 26.5 | 18.8–126 | |||||

| Day 21 | Ingestive (sucrose) | Control | 8 | 222 | 195.5–255.5 | 7.5 | 0.004⁎ | −0.681 |

| Experimental | 10 | 156 | 125.3–176.3 | |||||

| Aversive (DB) | Control | 8 | 83 | 54–133.8 | 21 | 0.091 | −0.398 | |

| Experimental | 10 | 53 | 21.5–82.8 |

DB: denatonium benzoate; Q1–Q3: quartiles 1 and 3.

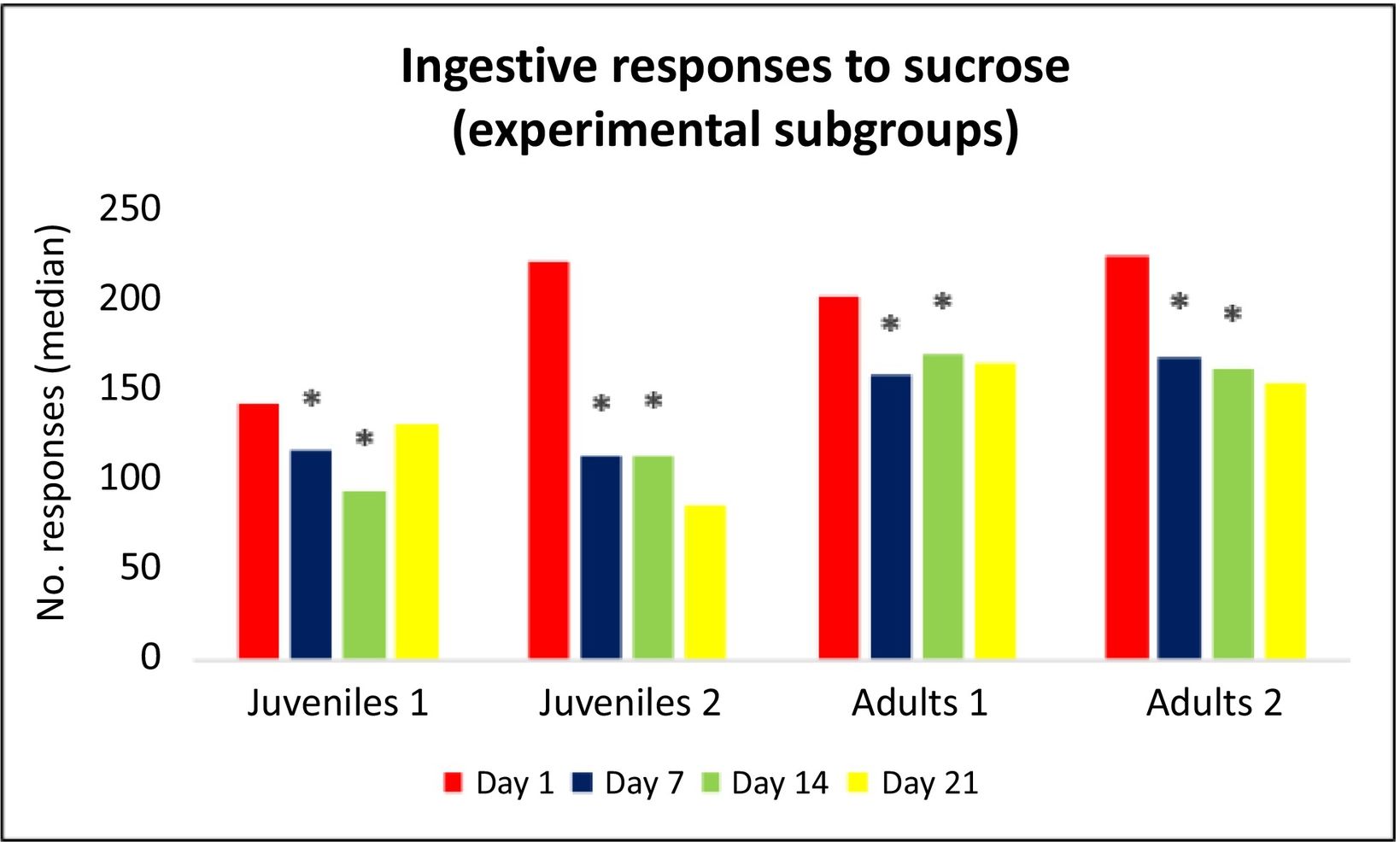

To conduct multiple comparisons of TRT responses between juvenile and adult rats, we created 4 subgroups based on body weight. For controls, the following groups were formed: juveniles 1 (n = 4; median weight [Q1–Q3] = 119 g [108.3–125.3]); juveniles 2 (n = 4; 132 g [128.8–150.3]); adults 1 (n = 4; 165 g [156.8–166.5]); adults 2 (n = 4; 178.5 g [172.8–182.8]). For experimental animals, the groups were as follows: juveniles 1 (n = 5; 130 g [128.3–131.8]); adults 2 (n = 4; 140 g [135.3–153.8]); adults 1 (n = 5; 156 g [150–159.8]); adults 2 (n = 58; 166.5 g 164.5–178.3).

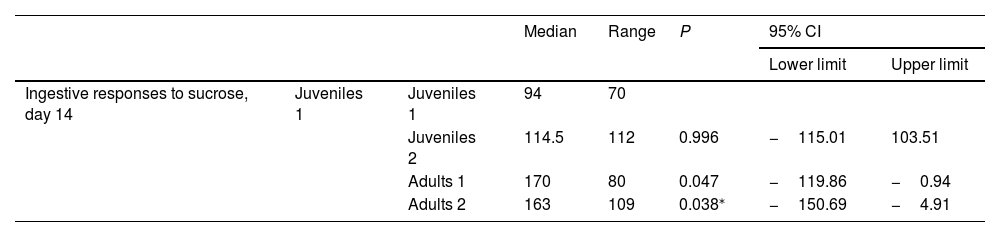

Results from multiple comparisons between juvenile and adult male Wistar ratsComparison of the number of ingestive responses to sucrose and aversive responses to DB between the 4 control subgroups and comparison of the number of aversive responses to DB between the 4 experimental subgroups revealed no statistically significant differences on days 1, 7, 14, or 21. Furthermore, comparison of the number of ingestive responses to sucrose in the 4 experimental subgroups identified no statistically significant differences at days 1 (H[3] = 6.305; P = .098) or 21 (H[3] = 6.818; P = .078). In contrast, we did observe differences on days 7 (H[3] = 8.697; P = .034) and 14 (H[3] = 10.958; P = .012) (Fig. 3). However, post hoc analysis found no significant differences at day 7. On day 14, the adults 1 subgroup presented a higher number of ingestive responses than the juveniles 1 subgroup (median [Q1–Q3]: 170 [127–176.5] vs 94 [74–116.5]; P = .047); furthermore, the adults 2 subgroup presented a higher number of responses (163 [143.5–207]) than the juveniles 1 subgroup (P = .038) (Table 3).

Comparison of the number of ingestive responses to sucrose in juvenile and adult rats in the experimental group, on day 14.

| Median | Range | P | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||||

| Ingestive responses to sucrose, day 14 | Juveniles 1 | Juveniles 1 | 94 | 70 | |||

| Juveniles 2 | 114.5 | 112 | 0.996 | −115.01 | 103.51 | ||

| Adults 1 | 170 | 80 | 0.047 | −119.86 | −0.94 | ||

| Adults 2 | 163 | 109 | 0.038⁎ | −150.69 | −4.91 | ||

Post hoc Games-Howell test.

Four potential mechanisms have been proposed by which DD contributes to gustatory alterations, which cannot be attributed to direct gustatory nerve lesions: (1) following DD due to tooth extraction, inflammatory cells infiltrate into the surrounding tissue and damage peripheral nerves, including gustatory afferents, in a mechanism involving the neurotransmitter substance P, secreted by the trigeminal nerve.13,36 (2) Afferent signals from the trigeminal nerve converge with gustatory afferents at both the central and the peripheral levels, as the processing of multisensory information may occur in taste receptor cells (TRC), the rNST, or the gustatory cortex.36–38 (3) Another possible reason for the deterioration of taste buds and GP after tooth extraction may be the reduction in periodontal, pulpal, and mucosal mechanoreception.10,13 (4) Finally, DD associated with tooth extraction may affect saliva secretion, negatively influencing GP morphology or survival, or contribute to the degeneration of peripheral gustatory receptors.39,40

Our literature search identified no studies using the TRT to evaluate the correlation between gustatory alterations and DD due to the extraction of the upper molars. However, given that taste perception is derived from interaction between the facial (CT and greater superficial petrosal nerve), glossopharyngeal, and vagus nerves, with a somatosensory contribution from the trigeminal nerve, DD may have repercussions equivalent to those of sectioning the CT and glossopharyngeal nerve. In our study, application of the TRT in juvenile rats showed that DD affected the number of ingestive responses to sucrose in the experimental group, with statistically significant differences at days 7, 14, and 21. Similarly, adult rats in the experimental group showed a lower number of ingestive responses to sucrose, with statistically significant differences at days 14 and 21. When Grill and Schwartz41 compared the ingestive responses to sucrose infusion at different concentrations (0.01 M, 0.1 M, and 1.0 M) in rats with combined CT and glossopharyngeal nerve section (CTX and GPX, respectively), the control group showed a significant increase in ingestive responses in line with sucrose concentration. In contrast, CTX + GPX rats displayed significantly fewer ingestive responses overall than rats in the control group, for all sucrose concentrations evaluated.

Nearly all studies into taste aversion using the TRT, ever since the technique was first described by Grill and Norgren,14,15 have used quinine hydrochloride. DB is the most bitter substance known to exist: it is 3000 times more bitter than quinine, and its bitter taste persists even at a dilution of 1:100000000.42 Nonetheless, rats are unable to discriminate between 2 structurally distinct bitter compounds, despite the fact that these flavourings are thought to stimulate different TRCs.43 In the study by King et al.,44 3 surgical procedures were conducted in 83 rats: bilateral glossopharyngeal nerve transection, bilateral excision of 8–10 mm of the glossopharyngeal nerve, and a sham treatment in which the glossopharyngeal nerves were exposed. The authors observed that independently of the condition of the glossopharyngeal nerve, rats displayed very few (if any) aversive responses to water. Furthermore, animals with intact nerves (sham group) were the only ones to present numerous aversive responses to quinine infusion. In our study, juvenile rats in the experimental group displayed fewer aversive reactions to DB than control animals; this difference was statistically significant at day 21. Similarly, adult rats from the experimental group also showed a lower number of aversive responses, with a statistically significant difference at day 14.

Our study found no significant differences between the 4 control subgroups in ingestive responses to sucrose and aversive reactions to DB. Similarly, no differences in aversive reactions were observed between the 4 experimental subgroups. However, comparison of the 4 experimental subgroups did reveal statistically significant differences in ingestive responses to sucrose, except on days 1 and 21. In a study of adolescent and adult rats, Wilmouth and Spear45 reported that the sum of all ingestive responses to the 10% sucrose solution during the 45-s infusion period was significantly higher in adolescent rats. In the 30-s post-infusion period, responses were relatively low and did not significantly decrease with age, despite an apparent tendency for adult animals to show more responses than adolescent rats. Regarding aversive responses to water and quinine, adult rats presented a significantly higher number of aversive reactions to quinine with respect to the baseline value for water during the 45-s infusion period, whereas no difference was observed in adolescent animals. A similar pattern was observed during the 30-s post-infusion period, with adult rats showing higher numbers of aversive reactions to quinine than to water. In this study, responses were recorded in the last 30 s of the infusion phase and all 30 s of the post-infusion phase to score ingestive and aversive responses.

Although adult rats in the experimental group showed fewer aversive responses than controls on days 14 and 21, this difference was only statistically significant on day 14. One potential explanation is the existence of adaptive or compensatory mechanisms supporting gustatory function after molar extraction, as nerve damage in a given region may increase the remaining gustatory signals in neighbouring areas.11,13 This peripheral compensation may be associated with an increase in the number of TRCs per GP, or in the density of relevant molecular receptor sites on the apical membrane. In relation to this, a family of genes has been discovered that encode mammalian taste receptors that bind with bitter compounds, altering the function of posterior tongue taste receptors in rats with regenerated glossopharyngeal nerve.44

Male Wistar rats were used because of the findings of Clarke and Ossenkopp,32 who demonstrated that female rats display differences in taste sensitivity, modulated by their reproductive cycle: female rats in the dioestrus/proestrus period presented a higher number of ingestive responses than males to sucrose, quinine, and a sucrose/quinine mixture, and fewer aversive responses than male animals and females in the oestrus/metoestrus period. If we had used female rats, it would not have been possible to compare our results to those of similar studies, all of which have used male animals.

The limitations of our study include the lack of an infusion pump at our laboratory for the administration of appetitive and aversive solutions during the TRT. Studies using multiple solutions at different concentrations, or a mixture of solutions, generally use such a device.32,46 We compensated for this limitation by administering solutions with a 3 cc syringe over 60 s, using a stopwatch.

Finally, we conclude that DD negatively influences ingestive responses in juvenile rats at days 7, 14, and 21, whereas aversive responses are only affected at day 21. In adult animals, ingestive responses are affected at days 14 and 21, whereas aversive responses are only affected at day 14. Comparison of ingestive and aversive reactions between juvenile and adult rats in the experimental group identified significant differences in ingestive responses at days 7 and 14.

Sources of fundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation organization.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAlejandro Gutiérrez-Patiño Paúl: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. Elías Aguirre-Siancas: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

All experiments were approved by the research ethics committee of the faculty of medicine of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (project code 0054–2022).

The authors wish to thank Dr. Cesar Gavidia, Dr. Roberto Dávila, Dr. Rosina Camargo, and the laboratory assistant Zaida Carbajal. The present study is part of the doctoral thesis entitled “Influencia de la desaferentación dental sobre la variación del sentido del gusto de ratas albinas machos (jóvenes y adultos), Lima 2022” (Influence of dental deafferentation on taste variations in male albino rats [adult and juvenile], Lima 2022).