Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, with symptoms ranging from seizures to speech disorders. TBI often requires stabilization, neuroimaging, and correction of metabolic imbalances like dysnatremia, which can worsen outcomes. This study evaluates the relationship between dysnatremia, clinical parameters, and neuroimaging findings in acute TBI patients.

MethodsA multicenter retrospective cohort study was conducted in three hospitals in Guayaquil, Ecuador, including 200 ICU patients with acute TBI from 2018 to 2023. Data were collected from clinical histories, neuroimaging, and biochemical analyses, with serum sodium levels measured at admission, 24, and 48 h post-admission. Statistical analyses included Chi-square tests, Kruskal-Wallis tests, Pearson correlation, and logistic regression to assess associations.

ResultsOf the 200 patients, 85.5% were male. Alcohol consumption was higher in patients with dysnatremia (p = 0.010). Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and FOUR Scale scores were lower in hypernatremic patients at both admission and 48 h (p < 0.001). Hypernatremia was linked to increased ventilatory support (94.5%) and higher mortality (41.8%) (p = 0.017). Neuroimaging showed associations between hypernatremia and subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral edema, and contusions (p < 0.05). Logistic regression revealed that higher GCS scores were linked to reduced mortality (OR = 0.717, p < 0.001).

ConclusionsHypernatremia correlates with lower neurological scores, abnormal neuroimaging findings, increased ventilatory support, and higher mortality in patients with acute TBI. Serum sodium monitoring may aid early risk stratification and guide critical care interventions. Prospective studies are warranted to standardize protocols and optimize dysnatremia management in TBI.

La lesión cerebral traumática (LCT) es una causa importante de morbilidad y mortalidad, con síntomas que van desde convulsiones hasta trastornos del habla. La LCT a menudo requiere estabilización, neuroimagen y corrección de desequilibrios metabólicos como la disnatremia, que pueden empeorar los resultados. Este estudio evalúa la relación entre la disnatremia, los parámetros clínicos y los hallazgos de neuroimagen en pacientes con LCT aguda.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio de cohortes retrospectivo multicéntrico en tres hospitales de Guayaquil, Ecuador, que incluyó 200 pacientes de la UCI con TBI agudo desde 2018 hasta 2023. Se recopilaron datos de historias clínicas, neuroimágenes y análisis bioquímicos, con niveles de sodio sérico medidos al ingreso, 24 y 48 horas después del ingreso. Los análisis estadísticos incluyeron pruebas de Chi cuadrado, pruebas de Kruskal-Wallis, correlación de Pearson y regresión logística para evaluar las asociaciones.

ResultadosDe los 200 pacientes, el 85,5% eran varones. El consumo de alcohol fue mayor en los pacientes con disnatremia (p = 0,010). Las puntuaciones de la Escala de Coma de Glasgow (GCS) y la Escala FOUR fueron inferiores en los pacientes hipernatrémicos tanto al ingreso como a las 48 horas (p < 0,001). La hipernatremia se relacionó con un mayor soporte ventilatorio (94,5%) y una mayor mortalidad (41,8%) (p = 0,017). La neuroimagen mostró asociaciones entre hipernatremia y hemorragia subaracnoidea, edema cerebral y contusiones (p < 0,05). La regresión logística reveló que las puntuaciones más altas de GCS estaban relacionadas con una menor mortalidad (OR = 0,717, p < 0,001).

ConclusionesLa hipernatremia se correlaciona con puntuaciones neurológicas más bajas, hallazgos de neuroimagen anormales, mayor soporte ventilatorio y mayor mortalidad en pacientes con TCE agudo. La monitorización del sodio sérico puede ayudar a la estratificación temprana del riesgo y guiar las intervenciones de cuidados críticos. Se justifica la realización de estudios prospectivos para estandarizar los protocolos y optimizar el tratamiento de la disnatremia en la LCT.

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a type of injury caused by traumatic events with variable kinematics that significantly affect the brain, representing one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in polytraumatized patients.1,2 The clinical presentation can be diverse; some patients initially present with headache, warning signs such as seizures, or even coma, the latter sometimes associated with symptomatic dysnatremias. In other cases, dysnatremias may be incidentally detected or remain asymptomatic.1 TBI evaluation in the emergency setting is based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), which ranges from 3 to 15 points. According to this assessment, brain injury is classified as mild (13–15), moderate (9–12), or severe (3–8).3

The mechanisms of TBI can be broadly classified into high-impact and low-impact events. High-impact mechanisms, including motor vehicle collisions, assaults, and sports-related injuries, are often associated with diffuse axonal injury and severe neurological damage.4 Conversely, low-impact mechanisms —primarily falls—are particularly prevalent among the elderly and can lead to significant morbidity due to age-related cerebral atrophy and vascular fragility.5

The management of acute TBI requires a multidisciplinary approach, prioritizing patient stabilization, neuroimaging evaluation, and the identification and correction of metabolic disturbances.2,6,7 Neuroimaging has become one of the primary tools for the timely diagnosis of TBI, with non-contrast computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) being the most employed modalities. Frequent anomalies identified through neuroimaging in TBI include microhemorrhages, often associated with diffuse axonal injury; cerebral contusions; cerebral atrophy, typically linked to neurodegenerative processes; skull fractures; epidural and subdural hematomas; traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage; intraventricular hemorrhage; and penetrating injuries.6,7 The morbidity and mortality associated with these injuries correlate with high scores on prognostic tools such as the Marshall Classification for Traumatic Brain Injuries (MCTBI) or the Rotterdam CT Score.7 Pre-existing medical and psychiatric conditions also play a critical role in the prognosis of patients with TBI. Disorders such as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, substance use disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been associated with an increased risk of sustaining TBI and with worse clinical outcomes, including prolonged hospital stays and higher mortality rates.8 Additionally, a prior history of epilepsy predisposes patients to post-traumatic seizures, further complicating recovery.9

Among the factors known to worsen the prognosis of TBI, dysnatremias are particularly noteworthy. Dysnatremia refers to an imbalance in serum sodium levels, classified as hyponatremia (<135 mmol/L) or hypernatremia (>145 mmol/L). Due to the anatomical location of the pituitary gland at the base of the brain, its endocrine regulatory function can be compromised after a traumatic injury, leading to hormonal secretion abnormalities such as the Syndrome of Inadequate Secretion of Antidiuretic Hormone (SIADH) or the Cerebral Salt-Wasting Syndrome (CSWS). These conditions can provoke hyponatremia and contribute to cerebral edema. Dysnatremias may also result from disturbances in the body's water balance regulation system. Also, hypernatremia cases, such as those associated with diabetes insipidus, may arise.10,11 Early detection and management of these alterations are essential for reducing morbidity and mortality in TBI patients. This study aims to assess the presence of dysnatremias and their relationship with clinical parameters and neuroimaging findings in patients with acute traumatic brain injury, to inform appropriate, individualized management strategies.

MethodologyThe STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were used to verify the structure and results of our study. Ethical approval for the contribution of data was granted by each participating hospital.

Study designThis multicenter study employs a cohort, observational, retrospective, and analytical methodology, performed in tertiary care hospital centers recognized for their expertise in the management of traumatic brain injury. Two third-level complexity specialty hospitals and one second-level complexity general hospital were included, located in the city of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Data collection was carried out from clinical history, images, and laboratory analysis of admitted patients due to acute head trauma between 2018 and 2023.

Population studyA retrospective collection of clinical data from patients admitted to the Intensive Care Units (ICU) was conducted. The initial sample consisted of 246 patients, of whom 46 were excluded due to incomplete clinical records. A total of 200 patients were included based on the following criteria: age between 18 and 65 years, admission to the ICU for acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) between 2018 and 2023 in the participating hospitals, neuroimaging findings consistent with acute TBI, and availability of serum sodium measurements at admission and 48 h post-admission. Patients were excluded if they had incomplete clinical records, a documented history of dysnatremia, or had already started treatment to correct sodium disorders before ICU admission. Patients who died within the first 24 h of ICU admission were also excluded, as it was not possible to obtain complete sodium data for analysis.

To ensure consistency and reliability across the different hospitals, data collection was standardized through the use of a unified database. All clinical, laboratory, and imaging data were reviewed by multiple researchers independently to verify accuracy and coherence before inclusion in the final dataset.

VariablesSociodemographic variables were used to characterize the population, including age and sex, as well as personal and social history such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, prior surgeries, and toxic habits (e.g., alcohol or drug use). To assess the level of consciousness and severity of traumatic brain injury (TBI), the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was applied both at admission and during hospitalization. Additionally, the FOUR Score (Full Outline of Unresponsiveness) was used. This neurological assessment tool evaluates four components: eye response, motor response, brainstem reflexes, and respiratory pattern. Unlike the GCS, the FOUR Score can be particularly useful in intubated or deeply unconscious patients, offering a more comprehensive evaluation of brain function in critical care settings.

The mechanism of injury was categorized based on kinematics into low-energy and high-energy trauma. Low-energy mechanisms included ground-level falls and non-violent accidental impacts. High-energy mechanisms included falls from height, assaults (violence), motor vehicle collisions, and work-related injuries, which are typically associated with greater kinetic force and a higher risk of severe brain injury. Additional clinical variables included the duration of ICU stay, the need for mechanical ventilation, total hospital length of stay, and in-hospital mortality.

Finding definition in neuroimagingNeuroimaging data were collected, including the Marshall Scale score, the number and type of lesions identified (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, contusion, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, foreign body, diffuse axonal injury, cerebral edema and subgaleal hematoma), as well as such as the presence and location of fractures.

Sodium measurementSerum sodium levels were measured upon admission to the ICU and again at 24- and 48-h post-admission. The development of dysnatremia, including SIADH, diabetes insipidus, and salt-wasting brain syndrome, was monitored.

Statistical analysisData were input into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 29.0 (IBM Corp.; New York, United States of America). Qualitative variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, while the quantitative variables were described using means and standard deviations. Normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, with results reported as means and standard deviations. To demonstrate the association between quantitative variables, Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed. Categorical data were analyzed with Pearson's Chi-square test. The correlation between serum sodium and the variables studied (clinical and radiological) was determined using the Pearson Correlation Coefficient. Lastly, logistic regression was applied to relate the quantitative variables to the development of mortality.

ResultsA total of 200 ICU patients with acute TBI were included. Most patients were male (85.5%), with no statistically significant age differences among sodium groups. Clinical and demographic data were categorized according to serum sodium levels at two different time points: upon admission (Table 1) and 48 h post-admission (Table 2), recognizing that patients may have changed sodium status over time and therefore shifted between categories. Notably, alcohol use showed no statistically significant difference among sodium groups at admission, with 24.3% of hyponatremic, 13.4% of normonatremic, and 22.2% of hypernatremic patients reporting alcohol consumption (p = 0.194). However, when categorized by sodium levels at 48 h post-admission (Table 2), alcohol use was significantly associated with dysnatremia. Specifically, 28.6% of hyponatremic and 25.5% of hypernatremic patients reported alcohol use, compared to only 10.3% of normonatremic patients (p = 0.010). Other comorbidities, such as arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus, did not show significant differences between sodium groups at admission or upon 48 h post-admission.

Sociodemographic features and their association with dysnatremia upon admission.

| Variable | Hyponatremia(<135 mEq/L)N = 37 | Normonatremia(135–145 mEq/L)N = 127 | Hypernatremia(>145 mEq/L)N = 36 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex (%) | 89.2% | 87.4% | 75.0% | 0.137 |

| Age (years) | 39 ± 21 | 35 ± 18 | 41 ± 18 | 0.120 |

| Drug use (%) | 8.1% | 5.5% | 5.6% | 0.836 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 24.3% | 13.4% | 22.2% | 0.194 |

| Diabetes (%) | 21.6% | 11.8% | 8.3% | 0.194 |

| Arterial hypertension (%) | 21.6% | 13.4% | 11.1% | 0.373 |

| MOI: High-energy trauma (%) | 75.7% | 65.4% | 86.1% | 0.074 |

| Surgical procedure (%) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.394 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 12 ± 4 | 10 ± 4 | 8 ± 3 | <0.001⁎ |

| FOUR Scale | 12 ± 4 | 9 ± 5 | 6 ± 4 | <0.001⁎ |

| Ventilatory support (%) | 62.2% | 81.1% | 91.8% | <0.001⁎ |

| Mortality (%) | 24.3% | 24.4% | 41.7% | 0.110 |

MOI = Mechanism of Injury.

Sociodemographic features and their association with their dysnatremia upon 48 h post-admission.

| Variable | Hyponatremia (<135 mEq/L)N = 28 | Normonatremia(135–145 mEq/L)N = 117 | Hypernatremia(>145 mEq/L)N = 55 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex (%) | 96.4% | 83.8% | 83.6% | 0.208 |

| Age (years) | 37 ± 16 | 35 ± 19 | 40 ± 19 | 0.140 |

| Drug use (%) | 10.7% | 6.0% | 3.6% | 0.439 |

| Alcohol use (%) | 28.6% | 10.3% | 25.5% | 0.010⁎ |

| Diabetes (%) | 14.3% | 16.2% | 5.5% | 0.143 |

| Arterial hypertension (%) | 14.3% | 14.5% | 14.5% | 0.999 |

| MOI: High-energy trauma (%) | 64.3% | 80.3% | 69.1% | 0.094 |

| Surgical procedure (%) | 3.6% | 4.3% | 3.6% | 0.973 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | 12 ± 4 | 11 ± 4 | 9 ± 3 | <0.001⁎ |

| FOUR Scale | 13 ± 4 | 9 ± 5 | 6 ± 5 | <0.001⁎ |

| Ventilatory support (%) | 57.1% | 80.3% | 94.5% | <0.001⁎ |

| Mortality (%) | 17.9% | 23.1% | 41.8% | 0.017⁎ |

MOI = Mechanism of Injury.

At 48 h post-admission, hypernatremia was associated with more severe neurological compromise. Patients with hypernatremia had significantly lower GCS and FOUR scores compared to those with normal or low sodium levels (p < 0.001 for both). The requirement for ventilatory support was markedly higher in the hypernatremic group (94.5%) relative to normonatremic (80.3%) and hyponatremic (57.1%) groups (p < 0.001). Mortality rates followed a similar trend, with hypernatremic patients experiencing the highest in-hospital mortality (41.8%), significantly greater than the normonatremic (23.1%) and hyponatremic (17.9%) groups (p = 0.017).

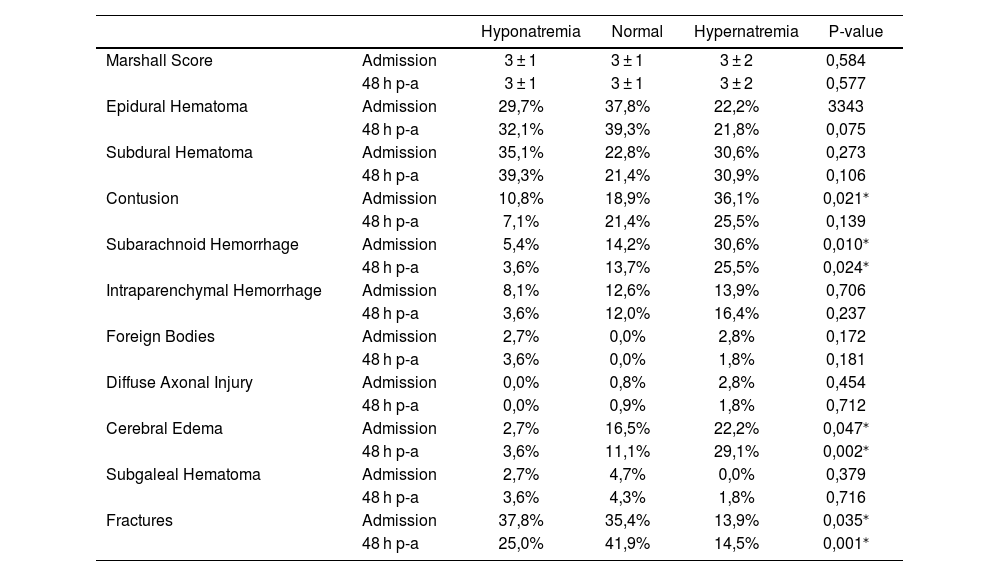

Radiological findings are detailed in Table 3. Subarachnoid hemorrhage was significantly more frequent among patients who developed hypernatremia, both at admission (p = 0.010) and at 48 h post-admission (p = 0.024). Cerebral edema also occurred more frequently in hypernatremic patients, with statistically significant differences at admission (p = 0.047) and 48 h (p = 0.002). Fractures were observed more frequently in the hyponatremic group at both admission (p = 0.035) and 48 h (p = 0.001). Additionally, contusions were more prevalent in the hypernatremic group upon admission (p = 0.021). There were no statistically significant differences across sodium groups for other neuroimaging features such as subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, or diffuse axonal injury.

Association of dysnatremia with neuroimaging.

| Hyponatremia | Normal | Hypernatremia | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marshall Score | Admission | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 2 | 0,584 |

| 48 h p-a | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 2 | 0,577 | |

| Epidural Hematoma | Admission | 29,7% | 37,8% | 22,2% | 3343 |

| 48 h p-a | 32,1% | 39,3% | 21,8% | 0,075 | |

| Subdural Hematoma | Admission | 35,1% | 22,8% | 30,6% | 0,273 |

| 48 h p-a | 39,3% | 21,4% | 30,9% | 0,106 | |

| Contusion | Admission | 10,8% | 18,9% | 36,1% | 0,021⁎ |

| 48 h p-a | 7,1% | 21,4% | 25,5% | 0,139 | |

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage | Admission | 5,4% | 14,2% | 30,6% | 0,010⁎ |

| 48 h p-a | 3,6% | 13,7% | 25,5% | 0,024⁎ | |

| Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage | Admission | 8,1% | 12,6% | 13,9% | 0,706 |

| 48 h p-a | 3,6% | 12,0% | 16,4% | 0,237 | |

| Foreign Bodies | Admission | 2,7% | 0,0% | 2,8% | 0,172 |

| 48 h p-a | 3,6% | 0,0% | 1,8% | 0,181 | |

| Diffuse Axonal Injury | Admission | 0,0% | 0,8% | 2,8% | 0,454 |

| 48 h p-a | 0,0% | 0,9% | 1,8% | 0,712 | |

| Cerebral Edema | Admission | 2,7% | 16,5% | 22,2% | 0,047⁎ |

| 48 h p-a | 3,6% | 11,1% | 29,1% | 0,002⁎ | |

| Subgaleal Hematoma | Admission | 2,7% | 4,7% | 0,0% | 0,379 |

| 48 h p-a | 3,6% | 4,3% | 1,8% | 0,716 | |

| Fractures | Admission | 37,8% | 35,4% | 13,9% | 0,035⁎ |

| 48 h p-a | 25,0% | 41,9% | 14,5% | 0,001⁎ | |

P-A: Post-Admission.

Spearman's correlation analysis demonstrated significant associations between dysnatremia and several key clinical variables both at admission and 48 h post-admission (Table 4). At admission, dysnatremia showed a moderate negative correlation with the GCS (rho = −0.294, p < 0.001) and the FOUR scale (rho = −0.347, p < 0.001), indicating that patients with sodium disturbances had worse neurological status. Additionally, the need for ventilatory support correlated positively with dysnatremia at admission (rho = 0.308, p < 0.001), suggesting increased respiratory compromise in these patients. At 48 h post-admission, these correlations remained significant and slightly strengthened: GCS (rho = −0.335, p < 0.001), FOUR scale (rho = −0.385, p < 0.001), and ventilatory support (rho = 0.282, p < 0.001). Furthermore, mortality showed a significant positive correlation with dysnatremia at 48 h (rho = 0.192, p = 0.006), suggesting an association between sodium imbalance and increased risk of death. No significant correlations were found between dysnatremia and sex, age, drug or alcohol use, diabetes, arterial hypertension, or surgical procedure at either time point.

Correlation of dysnatremia with clinical variables.

| Variables | Admission | 48 h post-admission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rho de Spearman correlation | p-value | Rho de Spearman correlation | p-value | |

| Sex | 0,094 | 0,184 | 0,087 | 0,223 |

| Age | 0,044 | 0,538 | 0,051 | 0,479 |

| Drugs | −0,02 | 0,774 | −,086 | 0,227 |

| Alcohol | 0,033 | 0,642 | 0,043 | 0,544 |

| Diabetes | −0,132 | 0,062 | −,112 | 0,115 |

| Arterial Hypertension | −0,102 | 0,152 | 0,002 | 0,980 |

| Surgical Procedure | −0,134 | 0,058 | −0,004 | 0,952 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale | −0,294⁎⁎ | <,001⁎ | −0,335⁎⁎ | <,001⁎ |

| FOUR Scale | −0,347⁎⁎ | <0,001⁎ | −0,385⁎⁎ | <0,001⁎ |

| Ventilatory Support | 0,308⁎⁎ | <0,001⁎ | 0,282⁎⁎ | <0,001⁎ |

| Mortality | 0,087 | 0,219 | 0,192⁎⁎ | 0,006⁎ |

Spearman's correlation analysis revealed several significant associations between dysnatremia and neuroimaging findings both at admission and 48 h post-admission (Table 5). At admission, dysnatremia was positively correlated with the presence of subarachnoid hemorrhage (rho = 0.191, p = 0.007) and cerebral edema (rho = 0.179, p = 0.011), indicating that sodium imbalances were associated with these intracranial pathologies. Conversely, a significant negative correlation was observed between dysnatremia and fractures (rho = −0.175, p = 0.013). At 48 h post-admission, the positive correlations with subarachnoid hemorrhage (rho = 0.194, p = 0.006) and cerebral edema (rho = 0.247, p < 0.001) persisted and were slightly stronger, while the negative correlation with fractures remained significant (rho = −0.144, p = 0.042). No significant correlations were found between dysnatremia and Marshall Score, epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, contusions, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, foreign bodies, subgaleal hematoma, or diffuse axonal injury at either time point.

Correlation of dysnatremia with neuroimaging findings.

| Variables | Admission | 48 h post-admission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rho de Spearman correlation | p-value | Rho de Spearman correlation | p-value | |

| Marshall Score | −0,052 | 0,465 | −0,073 | 0,305 |

| Epidural Hematoma | −0,076 | 0,282 | −0,109 | 0,123 |

| Subdural Hematoma | −0,03 | 0,673 | −0,011 | 0,873 |

| Contusion | 0,116 | 0,103 | 0,123 | 0,83 |

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage | 0,191⁎⁎ | 0,007⁎ | 0,194⁎⁎ | 0,006⁎ |

| Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage | 0,09 | 0,203 | 0,114 | 0,107 |

| Foreign Bodies | −0,01 | 0,893 | -,013 | 0,851 |

| Diffuse Axonal Injury | 0,123 | 0,083 | 0,58 | 0,412 |

| Cerebral Edema | 0,179⁎ | 0,011⁎ | 0,247⁎⁎ | <,001⁎ |

| Subgaleal Hematoma | −0,027 | 0,708 | -,043 | 0,542 |

| Fracture | −0,175⁎ | 0,013⁎ | −0,144⁎ | 0,042⁎ |

Table 6 shows results from the logistic regression analysis identifying predictors of in-hospital mortality. Higher GCS scores were significantly associated with reduced mortality risk (OR = 0.717, 95% CI: 0.611–0.842; p < 0.001), indicating that for every point increase in GCS, the odds of death decreased by 28.3%. The FOUR score was also statistically significant (OR = 1.171, 95% CI: 1.051–1.306; p = 0.004); however, the positive association suggesting increased mortality with higher FOUR scores contradicts clinical expectations. This unexpected direction may reflect underlying collinearity with other variables, model interactions, or limitations in the retrospective dataset, and warrants further prospective investigation to clarify its predictive role.

Logistic Regression of mortality.

| Variable | OR | 95% C.I. | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0,725 | (0,256 – 2054) | 0,545 |

| Age | 1015 | (0,992 – 1037) | 0,197 |

| Drugs | 1170 | (0,263 – 5206) | 0,837 |

| Alcohol | 0,464 | (0,166 – 1294) | 0,142 |

| Diabetes | 1201 | (0,367 – 3931) | 0,762 |

| Arterial Hypertension | 1074 | (0,342 – 3366) | 0,903 |

| Glasgow Scale at Admission | 1042 | (0,913 – 1190) | 0,538 |

| Glasgow Scale at Hospitalization | 0,717 | (0,611 – 0,842) | <0,001⁎ |

| Four Scale | 1171 | (1051 – 1306) | 0,004⁎ |

| Marshall Score | 0,855 | (0,640 – 1143) | 0,290 |

| ICU Stay | 0,987 | (0,941 – 1034) | 0,578 |

| Hospitalization Days | 0,990 | (0,957 – 1025) | 0,584 |

| Ventilatory Support | 3249 | (0,280 – 37,686) | 0,346 |

| ICU | 1229 | (0,125 – 12,091) | 0,860 |

| Sodium 24 h | 1000 | (0,875 – 1142) | 0,999 |

| Sodium 48 h | 1048 | (0,953 – 1153) | 0,335 |

ICU = Intensive Care Unit.

In the final multivariable regression model, after adjusting for potential confounders, the GCS remained the only statistically significant independent predictor of in-hospital mortality (p < 0.001), with each additional GCS point associated with a 19.6% reduction in the odds of death (OR = 0.804, CI: 0.728–0.888).

This highlights the robustness and clinical utility of the GCS as a prognostic tool in acute traumatic brain injury. Clinicians can rely on GCS scores as a key factor in early risk stratification and management decisions, while the role of the FOUR score requires additional investigation.

DiscussionThis study included 200 patients from ICUs across three hospitals in Guayaquil, Ecuador, all diagnosed with acute TBI. The male predominance (85.5%) is consistent with the known epidemiology of TBI, although no significant association was found between sex and dysnatremia. This result aligns with findings from previous studies, which also reported no strong gender-based predisposition to sodium imbalances in TBI patients.10,11

Furthermore, age did not show a significant correlation with dysnatremia in our sample, contrasting with the findings of Léveillé E et al. who reported a significant association between hyponatremia and older age (p = 0.007).12 One possible explanation for this discrepancy may lie in demographic differences across study populations or differences in comorbidity profiles, suggesting that age-related trends in dysnatremia may not be universally generalizable and warrant further study.

The relationship between alcohol use and sodium imbalance was significant 48 h post-admission (p = 0.010), with 28.6% of alcohol consumers presenting with hyponatremia. This suggests that alcohol use may contribute to sodium dysregulation during the acute phase of TBI, potentially through mechanisms such as the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, which has been previously implicated in brain injury-related hyponatremia.13,14

Neurological status, assessed via GCS and FOUR scores, was negatively correlated with serum sodium levels at both admission and 48 h. Lower scores were associated with hypernatremia (GCS: r = −0.294 and − 0.335; FOUR: r = −0.347 and − 0.385; both p < 0.001), indicating that patients with more severe neurologic impairment were at greater risk for elevated sodium levels. These findings support the observations of M. Li et al. and Philip M. et al. who also reported an association between lower Glasgow scores and hypernatremia (p < 0.001 and p = 0.047, respectively).15,16 The consistency of this relationship across multiple time points strengthens the argument that dysnatremia is both a marker and a potential contributor to TBI severity.

Hypernatremia was significantly associated with increased need for ventilatory support (94.5% at admission and 48 h, p < 0.001) and higher in-hospital mortality (41.8% at 48 h, p = 0.006). This aligns with the findings of Tverdal C. et al. who reported a 43-fold increased risk of death in patients with dysnatremia (OR = 43.5, 95% CI),10 and M. Li et al. who found that hypernatremia increased mortality risk by nearly 30-fold (p < 0.001).15 Philip M. et al. further emphasized the prognostic value of hypernatremia at admission and 48 h post-surgery, associating it with a 5.74- and 2.14-fold increased risk of 30-day mortality, respectively.16 These data highlight hypernatremia as a robust and independent predictor of poor outcomes in TBI patients.

Neuroimaging findings showed that hypernatremia was significantly associated with cerebral edema, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), and cerebral contusions both at admission and 48 h (p < 0.05). These results are in agreement with those of Philip M et al. who also found associations between hypernatremia and subdural hematoma (p = 0.044), midline shift >5 mm (p = 0.048), and absence/compression of basal cisterns (p = 0.010).16 The specific lesions varied across studies, but the consistent association between hypernatremia and radiologic evidence of intracranial pathology supports its role as a clinical warning sign. Similarly, Helliwell et al. noted hypernatremia as a risk factor for developing multiple lesions, including cerebral edema. These patterns reinforce the importance of serum sodium monitoring in evaluating neurologic injury severity.17 Conversely, our study also found significant associations between hyponatremia and skull fractures at admission (p = 0.035) and 48 h (p = 0.001). Lèveillé et al. reported a correlation between hyponatremia and various intracranial injuries, including hemorrhages (p = 0.027), though they did not specifically address fractures.12 While both studies confirm that hyponatremia may serve as a marker of traumatic burden, the specific type of radiologic lesion may vary depending on clinical context and severity.

Interestingly, our study did not find a significant association between dysnatremia and the Marshall classification of TBI severity. This contrasts with the findings of Lèveillé et al. and Cholakkal et al. who reported that hyponatremia was associated with higher Marshall scores (p = 0.007 and p = 0.013, respectively).12,18 The discrepancy may be due to sample heterogeneity or differences in the timing of neuroimaging. More standardized radiologic evaluation across time points could improve comparability in future studies.

Logistic regression analysis confirmed GCS as a strong predictor of mortality (p < 0.001), with each unit increase reducing mortality by 28.3% (OR = 0.717, 95% CI: 0.611–0.842). This mirrors findings by Mkubwa et al. who reported a 32% reduction in mortality for each additional GCS point.19 These consistent results further validate the GCS as a reliable and independent prognostic indicator in acute TBI management.

The strong association between hypernatremia and adverse outcomes such as need for mechanical ventilation, neuroimaging abnormalities, and increased mortality emphasizes the need for early identification and correction of sodium imbalances in TBI patients. Routine sodium monitoring at admission and during the first 48 h should be a priority in ICU protocols, especially for those with severe neurologic compromise or neuroimaging findings suggestive of elevated intracranial pressure. Furthermore, these findings suggest that serum sodium levels may serve as a non-invasive biomarker to stratify risk and guide the intensity of care, including neuroprotective strategies and fluid management.

This multicenter study provides valuable insight into the clinical and radiological correlates of dysnatremia in patients with acute TBI, leveraging a robust sample of ICU patients from three major hospitals. By analyzing both admission and 48-h data, and incorporating a range of clinical scales, radiological findings, and outcomes, this study offers a comprehensive and clinically relevant perspective on a commonly overlooked prognostic factor in neurocritical care. The consistent associations observed between dysnatremia, particularly hypernatremia, and poor neurologic scores, imaging abnormalities, need for mechanical ventilation, and mortality reinforce the clinical significance of early sodium monitoring in this population. As with any retrospective study, there are inherent limitations. The reliance on medical records may introduce some variability due to differences in documentation practices across centers. While sodium levels were measured at defined time points, continuous monitoring could have provided a more nuanced picture of fluctuations over time. Additionally, variations in imaging protocols among institutions may have influenced the classification of certain radiologic findings. Although the study cohort was drawn from a single city, it included patients from multiple institutions and thus offers a valuable snapshot of ICU care in a high-volume urban setting. Future prospective studies with standardized protocols and real-time monitoring of serum sodium and fluid management would help refine our understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved. Expanding the sample to include patients across a broader range of TBI severities and care settings would also enhance generalizability and facilitate the identification of high-risk subgroups.

ConclusionThis multicenter study demonstrated a significant association between dysnatremia, particularly hypernatremia, and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), including an increased need for mechanical ventilation and higher in-hospital mortality. These findings position hypernatremia as a strong predictor of poor prognosis in TBI patients. In contrast, no significant correlation was observed between dysnatremia and demographic variables such as age or gender. Hypernatremia was also linked to lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and FOUR scores and is in consequence to a contributor and a marker of severe neurologic impairment. Radiological findings demonstrated that hypernatremia was frequently associated with cerebral edema, contusions, and subarachnoid hemorrhage, while hyponatremia was more commonly observed in cases involving skull fractures. Alcohol use relationship to sodium imbalance, specifically hyponatremia, was significant at 48 h post-admission.

These findings underscore the prognostic value of early serum sodium assessment in neurocritical care. Dysnatremia, especially hypernatremia, may serve as a reliable marker of disease severity and a predictor of poor neurological and clinical outcomes. Incorporating routine sodium monitoring into ICU protocols may facilitate early risk stratification and support timely interventions aimed at improving patient outcomes. Future research should focus on prospective studies with standardized neuroimaging and a continuous 7-day sodium monitoring to further clarify the pathophysiological role of dysnatremia in TBI. Broader sampling across different healthcare settings will improve generalization and contribute to the development of targeted management strategies for high-risk populations.

ContributionPGR, ACHP, DPC, CRA, LIVP, ANM and RCM wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All co-authors edited the manuscript and approved the final content. All co-authors collected the information from the patient records of the intensive care unit patients. VC made the final corrections, and all co-authors approved the final manuscript.

Compliance, authorship, and originality statementsThis manuscript complies with all instructions to authors as specified by the journal. All authors meet the authorship requirements, and the final manuscript has been approved by all authors. Additionally, this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal.

Ethical guidelines and approvalsThis study adheres to ethical guidelines. Ethical approval (IRB) was obtained from each participating hospital, and informed consent was appropriately used. As this is a retrospective study, a statement regarding IRB approval is included.

Conflicts of interest disclosureThere was no conflict of interests among the authors of this paper.

Reporting checklistThe STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were used to verify the structure and results of this study.

Funding sourcesThis study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.