Cognitive impairments are one of the most common, insidious, and disabling symptoms of post-COVID-19 syndrome (PC-19), which have been correlated with damage to different brain structures.

ObjectiveTo describe cognitive impairments in PC-19, identify associated variables, and compare the impact of mechanical ventilation on cognitive and neuroimaging outcomes.

MethodsA cohort of COVID-19 survivors was evaluated with neuropsychological tests (NPT) and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 12 weeks after hospital discharge. Patients were classified into two groups based on whether they required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) or non-invasive mechanical ventilation (nIMV).

Results60 patients completed the study, 41 received IMV and 19 nIMV, with an average age of 57.11 years. 66% scored below 26 points on the MoCA test and 83.3% reported everyday memory failures (EMF). 85% showed impairments in at least one NPT. When comparing results between groups, significant differences were observed in the total MoCA test score (P = .045) and EMF (P = .032). Significant relationships were observed between the Boston Naming Test (−0.287; P = .035), the Rey Figure Recall Test (−0.324; P = .017) with parietal atrophy, as well as phonological verbal fluency with frontal atrophy (−0.276; P = .042). The HVLT (learning trial) test was related to hippocampal hyperintensity (−0.266; P = .050) and cingulate hyperintensity (0.311; P = .021). The TMT-B test was related to white matter hyperintensity (0.345; P= .010). The presence of poor functional prognosis was correlated with anxiety (P < .001), depression (P < .001), elevated D-dimer levels (P = .002) and the increase in days of intubation (P = .005).

ConclusionOur study suggests that COVID-19 survivors who had moderate-to-severe infection experience subjective complaints and cognitive impairments in executive function, attention, and memory, regardless of whether invasive mechanical ventilation was used during treatment. We found white matter lesions and cerebral atrophy in frontal and parietal regions that were associated with cognitive deficits. Our findings highlight the clinical need for longitudinal programmes capable of evaluating the real impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the central nervous system, particularly in the cognitive and emotional domains.

Las alteraciones cognitivas son uno de los síntomas más comunes, insidiosos e incapacitantes de síndrome post-COVID-19 (PC-19), las cuales se han correlacionado con daño en diferentes estructuras cerebrales.

ObjetivoDescribir alteraciones cognitivas PC-19, e identificar variables asociadas y comparar el impacto de la ventilación mecánica en los resultados cognitivos y de neuroimagen.

MétodosCohorte de personas sobrevivientes de COVID-19, evaluados después de 12 semanas del egreso hospitalario, con pruebas neuropsicológicas (PNP) y resonancia magnética de cráneo. Se clasificaron en dos grupos, los que requirieron ventilación mecánica invasiva (VMI) y los que tuvieron ventilación mecánica no invasiva (VMno-I).

Resultados60 pacientes completaron el estudio, 41 tuvieron VMI y 19 VMno-I, edad promedio de 57,11 años. El 66% obtuvo puntaje menor a 26 puntos en MoCA y 83,3% refirió fallos de memoria en la vida cotidiana (FMVC). El 85% presentó alteraciones en al menos una PNP. Al comparar los resultados por grupos solo se observó diferencia significativa en el puntaje total del test de MoCA (p = 0,045) y en FMVC (p = 0,032). Al comparar los resultados cognitivos con los de imagen en toda la muestra se observó relación significativa entre la prueba de denominación de Boston (−.287; p = 0,035), la evocación de la figura de Rey (−.324; p = 0,017) con atrofia parietal, fluidez verbal fonológica con atrofia frontal (−.276; p = 0,042). La prueba HVLT (ensayo de aprendizaje) con hiperintensidad en hipocampo (−.266; p = 0,050) e hiperintensidad en cíngulo (.311; p = 0,021). La prueba TMT-B se relacionó con hiperintensidad en sustancia blanca (.345; p = 0,010). La presencia de mal pronóstico funcional se correlacionó con ansiedad (p < 0,001), depresión (p < 0,001), niveles elevados de dímero D (p = 0,002) y el aumento en los días de intubación (p = 0,005).

ConclusiónNuestro estudio sugiere que existen quejas subjetivas y alteraciones cognitivas en funciones ejecutivas, atención y memoria en pacientes que tuvieron infección moderada-grave por COVID 19, independientemente de emplear VMI invasivo o no durante el manejo de su padecimiento. Encontramos lesiones de sustancia blanca y atrofia cerebral en regiones frontales y parietales que se asocian a déficits cognitivos. Nuestros hallazgos destacan la necesidad clínica de programas longitudinales capaces de evaluar el impacto real de la infección por SARS CoV 2 en el sistema nervioso central, manifestadas en el área cognitiva y emocional.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus expanded rapidly across the globe, with a pandemic being declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020; to date, it has caused 6 548 492 deaths globally. Mexico has been one of the worst affected countries, with 7 576 730 confirmed cases and 333 764 deaths, as of April 2023.1 Symptoms have been described that persist after infection; as a group, these have been designated as post–COVID-19 syndrome or long COVID. Up to 85% of severe hospitalised patients and 35% of asymptomatic patients are estimated to present persistent symptoms at 12 weeks after the acute infection.2,3

Cognitive alterations are one the most frequent, insidious, and disabling symptoms of long COVID, with an impact on quality of life and long-term functional status. The majority of studies have reported alterations in executive functions, attention,4 memory,5 language,6 and visuospatial functions7 in hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients; these cognitive manifestations have also been associated with anxiety and depression symptoms.8

Likewise, they have been correlated with alterations in other brain structures. Delorme et al.9 describe frontal and cerebellar hypometabolism in patients with long COVID, with predominant involvement of the frontal lobe. Furthermore, Díez-Cirarda et al.10 reported a loss of cortical grey matter volume and hypoconnectivity between right and left hippocampal regions.

Different meta-analyses report that 53% of patients with long COVID present alterations on MRI studies and 23% in head CT studies, characterised by hyperintensities in the white matter, or hypodensities in the anterior and posterior white matter. Some changes have been observed in the insular cortex, subinsular region, cingulate gyrus, cerebral peduncle, internal capsule, thalami, midbrain, pons, parahippocampal gyrus, basal ganglia, splenium of the corpus callosum, and olfactory bulbs.11 Andriuta et al.12 report correlations between acute COVID-19 or long COVID and cognitive alterations, mainly in executive functions, language, and lesions to areas of the right hemisphere.

The duration of such alterations and their association with degenerative processes, or whether these processes may trigger the cognitive disorders, remain unknown.13

Several variables contribute to the progression and exacerbation of cognitive impairment in patients with long COVID; these include fatigue, hypoxaemia, delirium, and disease severity, among other factors.14–16 Zhou et al.17 assessed the impact of COVID-19 on cognitive function in recovered patients and its association with inflammatory profiles, observing that there are cognitive alterations mainly in attention and memory in patients who had recovered from COVID-19, and possibly associated with underlying inflammatory processes.

The need for mechanical ventilation during hospitalisation suggests that the severity of the disease has a significant impact on the presence of symptoms; however, few studies have assessed the persistence of symptoms in patients with severe COVID-19, more specifically in those needing invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV).18 Critical patients with COVID-19 may be predisposed to present a higher prevalence of symptoms, such as cognitive impairment and neuropsychiatric alterations.19 In contrast, patients who required non-invasive mechanical ventilation (nIMV) may develop more depressive symptoms attributed to exposure to significant stress due to the lack of contact with family members, as well as their awareness of their critical situation.20

For this study, we recruited a cohort of COVID-19 survivors who required hospitalisation, and performed neurological clinical assessment, measurement of inflammation markers, neuropsychological tests, functional status and neuropsychiatric assessments, and brain imaging studies, with the aim of describing cognitive alterations in long COVID and identifying associated variables. As a secondary objective, patients were subsequently divided into 2 groups to compare the impact of mechanical ventilation on cognitive and neuroimaging findings.

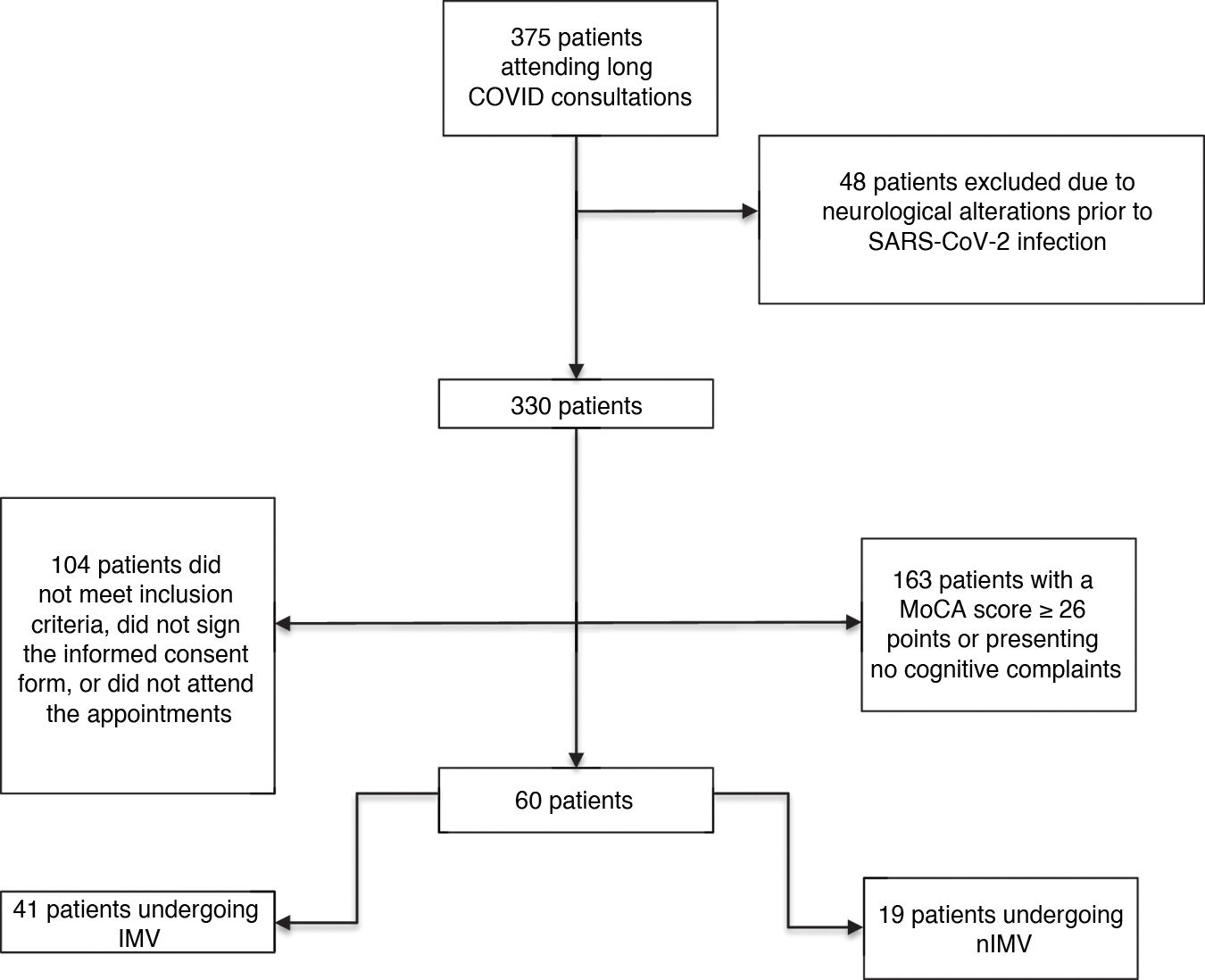

Material and methodsWe assessed a prospective cohort of 375 survivors of SARS-CoV-2 infection from the long COVID consultation at Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias (INER) at 12 weeks after discharge from hospital, during the period between December 2020 and April 2021.

We included patients aged older than 18 years, discharged from hospital with a diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed by PCR testing (oropharyngeal swab), who were admitted due to moderate and/or severe SARS-CoV-2 infection according to the WHO criteria (moderate disease: presence of clinical signs of pneumonia [fever, cough, dyspnoea and/or tachycardia], with no signs of severe pneumonia, and particularly room-air oxygen saturation [SaO2] ≥ 90%; severe disease: oxygen saturation [SpO2] < 90%, partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen ratio [PaO2/FiO2] < 300 mmHg, and respiratory frequency > 30 breaths per minute).21

With the aim of describing cognitive alterations in long COVID during the follow-up assessment of this cohort, we established several inclusion criteria: 1) Patients scoring > 26 points on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).222) Patients who reported subjective cognitive complaints, regardless of their MoCA score. 3) Patients meeting criteria for long COVID, and with cognitive symptoms that developed during SARS-CoV-2 infection and persisted after 12 weeks.23 Exclusion criteria included cognitive impairment prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection; intellectual, motor or sensory disability; and pre-existing neurological or psychiatric disease.

According to those criteria, we selected a group of 60 patients (Fig. 1) who were referred to the Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía Manuel Velasco Suárez (INNNMVS), where they underwent an extensive battery of neuropsychological tests (NPT) and a brain MRI study. Mean time from the onset of infection symptoms to the time of the cognitive and neuroimaging assessment was 122 days (SD: 21.25; range, 99–210).

All patients signed informed consent forms in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the INER (C48-20) and the INNNMVS (06-21).

Laboratory studiesThe following inflammatory markers were obtained for all patients, at admission and at 3 months after discharge: D-dimer, C-reactive protein, leukocyte count, total lymphocyte count, platelet count, glucose, urea, creatinine, fibrinogen, creatine phosphokinase (CPK), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

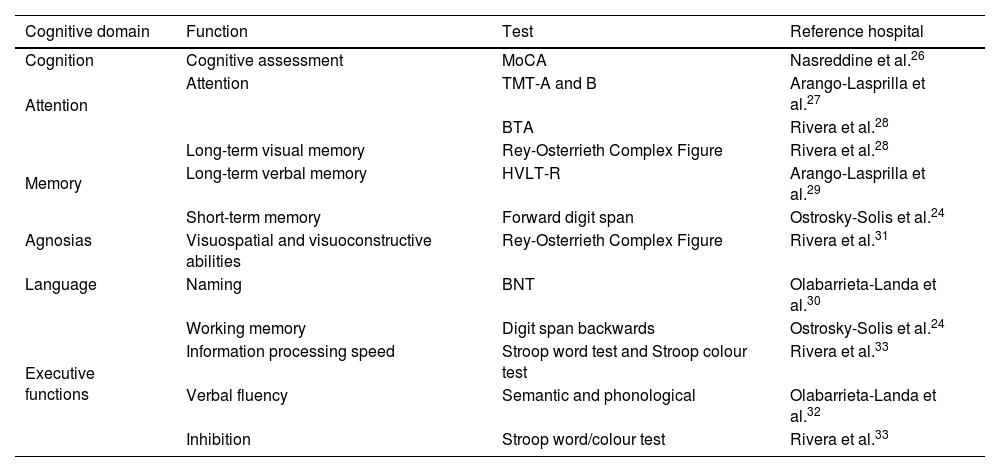

Neuropsychological assessmentSeveral NPTs standardised for the Mexican population and according to age and level of education were used to perform a comprehensive cognitive assessment (Table 1).24

Cognitive assessment tools.

| Cognitive domain | Function | Test | Reference hospital |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition | Cognitive assessment | MoCA | Nasreddine et al.26 |

| Attention | Attention | TMT-A and B | Arango-Lasprilla et al.27 |

| BTA | Rivera et al.28 | ||

| Memory | Long-term visual memory | Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure | Rivera et al.28 |

| Long-term verbal memory | HVLT-R | Arango-Lasprilla et al.29 | |

| Short-term memory | Forward digit span | Ostrosky-Solis et al.24 | |

| Agnosias | Visuospatial and visuoconstructive abilities | Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure | Rivera et al.31 |

| Language | Naming | BNT | Olabarrieta-Landa et al.30 |

| Executive functions | Working memory | Digit span backwards | Ostrosky-Solis et al.24 |

| Information processing speed | Stroop word test and Stroop colour test | Rivera et al.33 | |

| Verbal fluency | Semantic and phonological | Olabarrieta-Landa et al.32 | |

| Inhibition | Stroop word/colour test | Rivera et al.33 |

BTA: Brief Test of Attention; HVLT-R: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; TMT-A: Trail Making Test-Part A; TMT-B: Trail Making Test-Part B.

Z-scores were used to define normal and pathological results in the cognitive tests, with cognitive performance defined as low or very low for z-scores <−1 or <−2 standard deviations, respectively; this is equivalent to a percentile range from 1% to 25%, according to normative data for the Mexican population.24,25

The Memory Failures of Everyday Questionnaire (MFE) was used to assess subjective memory impairment.34 Furthermore, psychiatric symptoms were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale35 and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).36

Imaging studiesImaging studies consisted of brain MRI studies using a 3 T Siemens Magnetom Skyra MRI scanner. The following sequences and parameters were used: T1-weighted with a 250 mm field of view (FOV), 1.00 mm slice thickness, TR 2200 ms, TE 2.45 ms; FLAIR with a 240 mm FOV, 0.9 mm slice thickness, TR 5000 ms, TE 387 ms; T2-weighted with 256 mm FOV, 1.00 mm slice thickness, TR 3200 ms, TS 409 ms; diffusion-weighted imaging with a 220 mm FOV, 2.2 mm slice thickness, TR 5000 ms, TE 102.00 ms.

MRI findings were assessed by 2 neuroradiologists with extensive experience. For white matter lesions, the semiquantitative Fazekas visual assessment was used to evaluate T2-weighted and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences. The scale is scored by identifying the distribution of hyperintense white matter lesions (WML) in different brain regions, generally attributed to small-vessel disease. This scale uses 4 scoring grades: 0 (no WMLs), 1 (multiple isolated punctiform WMLs), 2 (WMLs beginning confluence), and 3 (WML in large confluent areas).37

Loss of brain volume was classified as frontal, temporal, parietal, or generalised. Qualitative grading systems developed to assess brain atrophy, especially in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, were used to assign degrees of severity. These systems included the generalised atrophy scale (global cortical atrophy or Pasquier scale), the posterior parietal atrophy scale (Koedam score), and the medial temporal atrophy scale (Scheltens scale); atrophy was rated with a score of 0 (absent), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe), as appropriate.38 In turn, volume loss was classified as cortical, subcortical, or cortico-subcortical.

Both neuroradiologists individually but simultaneously reviewed all brain images based on the scales defined in the literature to assign a degree of severity to both WMLs and loss of brain volume; in the event of disagreement, consensus was reached before issuing a joint rating.

Data management and statistical analysisFor the statistical analysis, we used the SPSS statistics software, version 22. Descriptive variables were analysed according to their distribution and expressed as frequencies and percentages or means and standard deviations. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to study the normality of the data distribution, and applied parametric or non-parametric statistics, depending on the results obtained.

Patients were divided into 2 groups: one included patients who required IMV and the other included those who required nIMV. We calculated deficit percentages for each neuropsychological test in each group, analysed according to Mexican normative data. We performed a bivariate analysis comparing each group according to the demographic, clinical, cognitive, and imaging variables, using the chi-square test and Fisher exact test for categorical variables, and the t test and/or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Correlations were analysed using Spearman rho coefficient, in 3 blocks: 1) neuropsychological assessment with laboratory studies; 2) neuropsychological assessment with imaging studies; and 3) neuropsychological assessment with neuropsychiatric symptoms. Lastly, we performed a partial correlation analysis, with the aim of determining the association between cognitive execution and imaging findings, controlled per group (IMV, nIMV). The level of significance was established at α < .05.

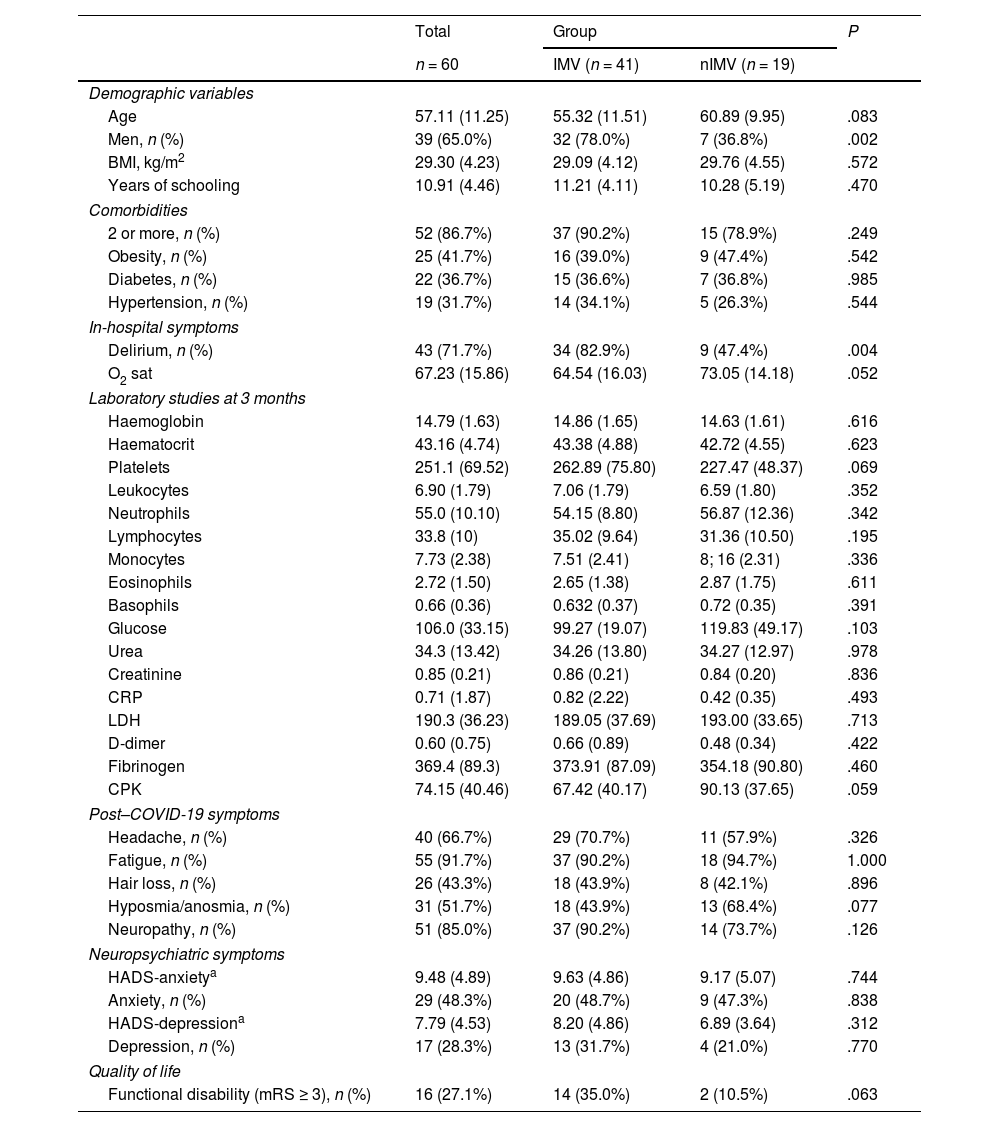

ResultsThe sample of 60 patients selected to undergo brain MRI study and neuropsychological assessment presented the following characteristics: mean age of 57.11 years, 65% men, and mean of 10.91 years of schooling. A total of 41.7% presented obesity, 36.7% diabetes, and 31.7% hypertension; the mean body mass index was 29.30 kg/m2.

Delirium was observed in 71.7% of patients during hospitalisation, and 86.7% presented 2 or more clinical comorbidities. The most frequently observed symptoms of long COVID were fatigue (91.7%) and neuropathy (85.0%) (Table 2).

Characteristics of the study population. Comparison between groups.

| Total | Group | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 60 | IMV (n = 41) | nIMV (n = 19) | ||

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age | 57.11 (11.25) | 55.32 (11.51) | 60.89 (9.95) | .083 |

| Men, n (%) | 39 (65.0%) | 32 (78.0%) | 7 (36.8%) | .002 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.30 (4.23) | 29.09 (4.12) | 29.76 (4.55) | .572 |

| Years of schooling | 10.91 (4.46) | 11.21 (4.11) | 10.28 (5.19) | .470 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| 2 or more, n (%) | 52 (86.7%) | 37 (90.2%) | 15 (78.9%) | .249 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 25 (41.7%) | 16 (39.0%) | 9 (47.4%) | .542 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 22 (36.7%) | 15 (36.6%) | 7 (36.8%) | .985 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 19 (31.7%) | 14 (34.1%) | 5 (26.3%) | .544 |

| In-hospital symptoms | ||||

| Delirium, n (%) | 43 (71.7%) | 34 (82.9%) | 9 (47.4%) | .004 |

| O2 sat | 67.23 (15.86) | 64.54 (16.03) | 73.05 (14.18) | .052 |

| Laboratory studies at 3 months | ||||

| Haemoglobin | 14.79 (1.63) | 14.86 (1.65) | 14.63 (1.61) | .616 |

| Haematocrit | 43.16 (4.74) | 43.38 (4.88) | 42.72 (4.55) | .623 |

| Platelets | 251.1 (69.52) | 262.89 (75.80) | 227.47 (48.37) | .069 |

| Leukocytes | 6.90 (1.79) | 7.06 (1.79) | 6.59 (1.80) | .352 |

| Neutrophils | 55.0 (10.10) | 54.15 (8.80) | 56.87 (12.36) | .342 |

| Lymphocytes | 33.8 (10) | 35.02 (9.64) | 31.36 (10.50) | .195 |

| Monocytes | 7.73 (2.38) | 7.51 (2.41) | 8; 16 (2.31) | .336 |

| Eosinophils | 2.72 (1.50) | 2.65 (1.38) | 2.87 (1.75) | .611 |

| Basophils | 0.66 (0.36) | 0.632 (0.37) | 0.72 (0.35) | .391 |

| Glucose | 106.0 (33.15) | 99.27 (19.07) | 119.83 (49.17) | .103 |

| Urea | 34.3 (13.42) | 34.26 (13.80) | 34.27 (12.97) | .978 |

| Creatinine | 0.85 (0.21) | 0.86 (0.21) | 0.84 (0.20) | .836 |

| CRP | 0.71 (1.87) | 0.82 (2.22) | 0.42 (0.35) | .493 |

| LDH | 190.3 (36.23) | 189.05 (37.69) | 193.00 (33.65) | .713 |

| D-dimer | 0.60 (0.75) | 0.66 (0.89) | 0.48 (0.34) | .422 |

| Fibrinogen | 369.4 (89.3) | 373.91 (87.09) | 354.18 (90.80) | .460 |

| CPK | 74.15 (40.46) | 67.42 (40.17) | 90.13 (37.65) | .059 |

| Post–COVID-19 symptoms | ||||

| Headache, n (%) | 40 (66.7%) | 29 (70.7%) | 11 (57.9%) | .326 |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 55 (91.7%) | 37 (90.2%) | 18 (94.7%) | 1.000 |

| Hair loss, n (%) | 26 (43.3%) | 18 (43.9%) | 8 (42.1%) | .896 |

| Hyposmia/anosmia, n (%) | 31 (51.7%) | 18 (43.9%) | 13 (68.4%) | .077 |

| Neuropathy, n (%) | 51 (85.0%) | 37 (90.2%) | 14 (73.7%) | .126 |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms | ||||

| HADS-anxietya | 9.48 (4.89) | 9.63 (4.86) | 9.17 (5.07) | .744 |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 29 (48.3%) | 20 (48.7%) | 9 (47.3%) | .838 |

| HADS-depressiona | 7.79 (4.53) | 8.20 (4.86) | 6.89 (3.64) | .312 |

| Depression, n (%) | 17 (28.3%) | 13 (31.7%) | 4 (21.0%) | .770 |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Functional disability (mRS ≥ 3), n (%) | 16 (27.1%) | 14 (35.0%) | 2 (10.5%) | .063 |

BMI: body mass index; CPK: creatine phosphokinase; CRP: C-reactive protein; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; nIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; O2 sat: oxygen saturation.

Values are expressed as means and standard deviations, unless otherwise indicated.

Sixty-six percent of the sample scored lower than 26 points on the MoCA, and 83.3% reported cognitive complaints, mainly related to memory and attention.

In the comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, 85% of patients presented alterations in at least one NPT. Executive function alterations were the most frequent, with 78.3% of patients presenting alterations in at least one of the tests, and 35% displaying alterations in at least 3.

Comparison between groups (IMV vs nIMV)We observed no statistically significant differences between groups regarding laboratory study results. Some total mean values were: leukocyte count of 6.90 cells/mm3, 33.81% lymphocytes, C-reactive protein 0.71 mg/dL, D-dimer 0.60 mg/L, and CPK 74.15 U/L.

We observed increased prevalence of delirium in the group that required IMV than among those who required nIMV (82.9% vs 47.4%; P = .004) (Table 2).

Regarding neuropsychiatric variables, no differences were observed between groups in depression or anxiety symptoms. As shown in Table 2, the IMV group scored 8.20 on the depression scale, whereas the nIMV group scored 6.89 points; this difference was not statistically significant (t = 1.02; P = .312). Anxiety was similar in both groups: 6.93 points in the IMV group vs 9.17 in the nIMV group (t = 328; P = .744).

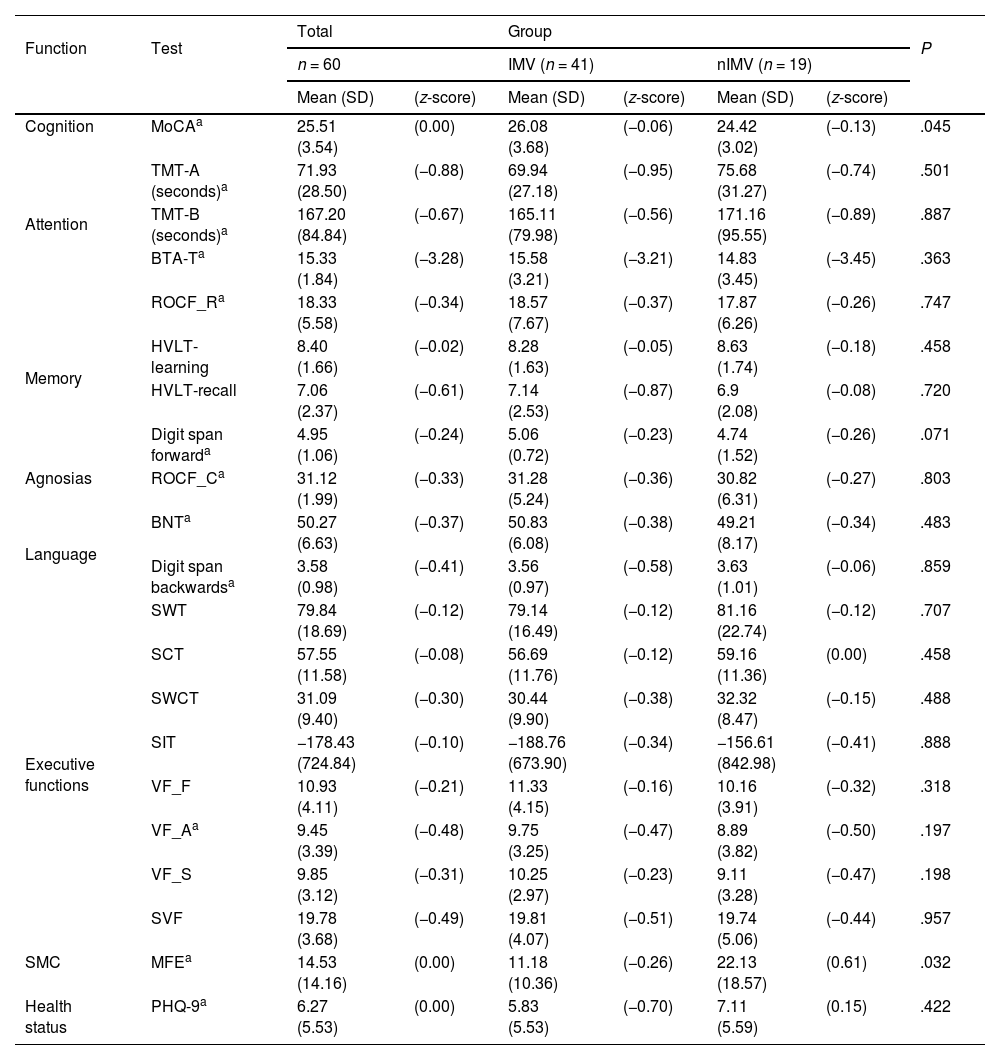

When comparing cognitive assessment results between groups, we only observed statistically significant differences in the total MoCA score (P = .045) and results on the MFE scale, in which the nIMV group obtained higher scores (mean of 22.13) than the IMV group (mean of 11.18) (P = .032). The scores on the remaining tests showed no statistically significant differences between groups (Table 3).

Results from the neuropsychological evaluation. Comparison between groups.

| Function | Test | Total | Group | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 60 | IMV (n = 41) | nIMV (n = 19) | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | (z-score) | Mean (SD) | (z-score) | Mean (SD) | (z-score) | |||

| Cognition | MoCAa | 25.51 (3.54) | (0.00) | 26.08 (3.68) | (−0.06) | 24.42 (3.02) | (−0.13) | .045 |

| Attention | TMT-A (seconds)a | 71.93 (28.50) | (−0.88) | 69.94 (27.18) | (−0.95) | 75.68 (31.27) | (−0.74) | .501 |

| TMT-B (seconds)a | 167.20 (84.84) | (−0.67) | 165.11 (79.98) | (−0.56) | 171.16 (95.55) | (−0.89) | .887 | |

| BTA-Ta | 15.33 (1.84) | (−3.28) | 15.58 (3.21) | (−3.21) | 14.83 (3.45) | (−3.45) | .363 | |

| Memory | ROCF_Ra | 18.33 (5.58) | (−0.34) | 18.57 (7.67) | (−0.37) | 17.87 (6.26) | (−0.26) | .747 |

| HVLT-learning | 8.40 (1.66) | (−0.02) | 8.28 (1.63) | (−0.05) | 8.63 (1.74) | (−0.18) | .458 | |

| HVLT-recall | 7.06 (2.37) | (−0.61) | 7.14 (2.53) | (−0.87) | 6.9 (2.08) | (−0.08) | .720 | |

| Digit span forwarda | 4.95 (1.06) | (−0.24) | 5.06 (0.72) | (−0.23) | 4.74 (1.52) | (−0.26) | .071 | |

| Agnosias | ROCF_Ca | 31.12 (1.99) | (−0.33) | 31.28 (5.24) | (−0.36) | 30.82 (6.31) | (−0.27) | .803 |

| Language | BNTa | 50.27 (6.63) | (−0.37) | 50.83 (6.08) | (−0.38) | 49.21 (8.17) | (−0.34) | .483 |

| Digit span backwardsa | 3.58 (0.98) | (−0.41) | 3.56 (0.97) | (−0.58) | 3.63 (1.01) | (−0.06) | .859 | |

| Executive functions | SWT | 79.84 (18.69) | (−0.12) | 79.14 (16.49) | (−0.12) | 81.16 (22.74) | (−0.12) | .707 |

| SCT | 57.55 (11.58) | (−0.08) | 56.69 (11.76) | (−0.12) | 59.16 (11.36) | (0.00) | .458 | |

| SWCT | 31.09 (9.40) | (−0.30) | 30.44 (9.90) | (−0.38) | 32.32 (8.47) | (−0.15) | .488 | |

| SIT | −178.43 (724.84) | (−0.10) | −188.76 (673.90) | (−0.34) | −156.61 (842.98) | (−0.41) | .888 | |

| VF_F | 10.93 (4.11) | (−0.21) | 11.33 (4.15) | (−0.16) | 10.16 (3.91) | (−0.32) | .318 | |

| VF_Aa | 9.45 (3.39) | (−0.48) | 9.75 (3.25) | (−0.47) | 8.89 (3.82) | (−0.50) | .197 | |

| VF_S | 9.85 (3.12) | (−0.31) | 10.25 (2.97) | (−0.23) | 9.11 (3.28) | (−0.47) | .198 | |

| SVF | 19.78 (3.68) | (−0.49) | 19.81 (4.07) | (−0.51) | 19.74 (5.06) | (−0.44) | .957 | |

| SMC | MFEa | 14.53 (14.16) | (0.00) | 11.18 (10.36) | (−0.26) | 22.13 (18.57) | (0.61) | .032 |

| Health status | PHQ-9a | 6.27 (5.53) | (0.00) | 5.83 (5.53) | (−0.70) | 7.11 (5.59) | (0.15) | .422 |

BNT: Boston Naming Test; BTA_T: Brief Test of Attention-total score; HVLT-learning: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-learning trial; HVLT-recall: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-recall; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; MFE: Memory Failures of Everyday Questionnaire; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; nIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; ROCF_C: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure-copy; ROCF_R: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure-recall; SCT: Stroop colour test; SIT: Stroop interference test; SMC: subjective memory complaints; SVF: semantic verbal fluency; SWCT: Stroop word/colour test; SWT: Stroop word test; TMT-A: Trail Making Test-Part A; TMT-B: Trail Making Test-Part B; VF_A: verbal fluency task-words beginning with A; VF_F: verbal fluency task-words beginning with F; VF_S: verbal fluency task-words beginning with S.

Values are expressed as mean (standard deviation) and z-score.

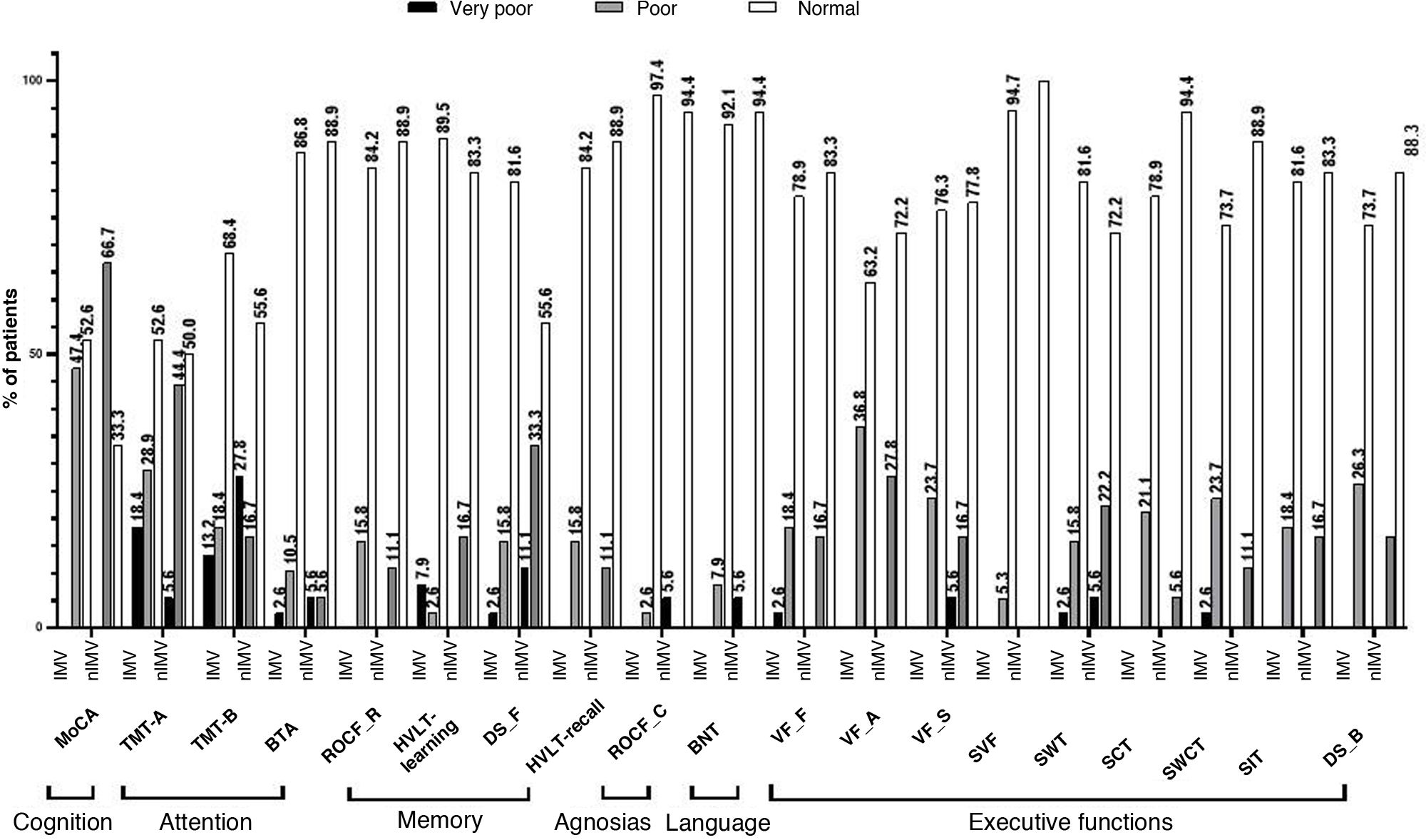

Using normalised data for the Mexican population, we observe that scores on several NPTs were below the cut-off point. In the IMV group, this was the case for 18.4% of patients in the Trail Making Test (TMT) part A, in 47.4% in the MoCA, and 36.8% in phonemic verbal fluency (VF) tasks. In the nIMV group, 27.8% scored below the cut-off point on the TMT part B, 44.4% on the TMT part A, and 66.7% on the MoCA (Fig. 2).

Performance in the neuropsychological assessment, by test.

BNT: Boston Naming Test; BTA: Brief Test of Attention-total score; DS_B: digit scan backwards; DS_F: digit span forward; HVLT-learning: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-learning trial; HVLT-recall: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-recall trial; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; ROCF_C: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure-copy; ROCF_R: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure-recall; SCT: Stroop colour test; SIT: Stroop interference test; SVF: semantic verbal fluency; SWCT: Stroop word/colour test; SWT: Stroop word test; TMT-A: Trail Making Test-Part A; TMT-B: Trail Making Test-Part B; VF_A: verbal fluency task-words beginning with A; VF_F: verbal fluency task-words beginning with F; VF_S: verbal fluency task-words beginning with S.

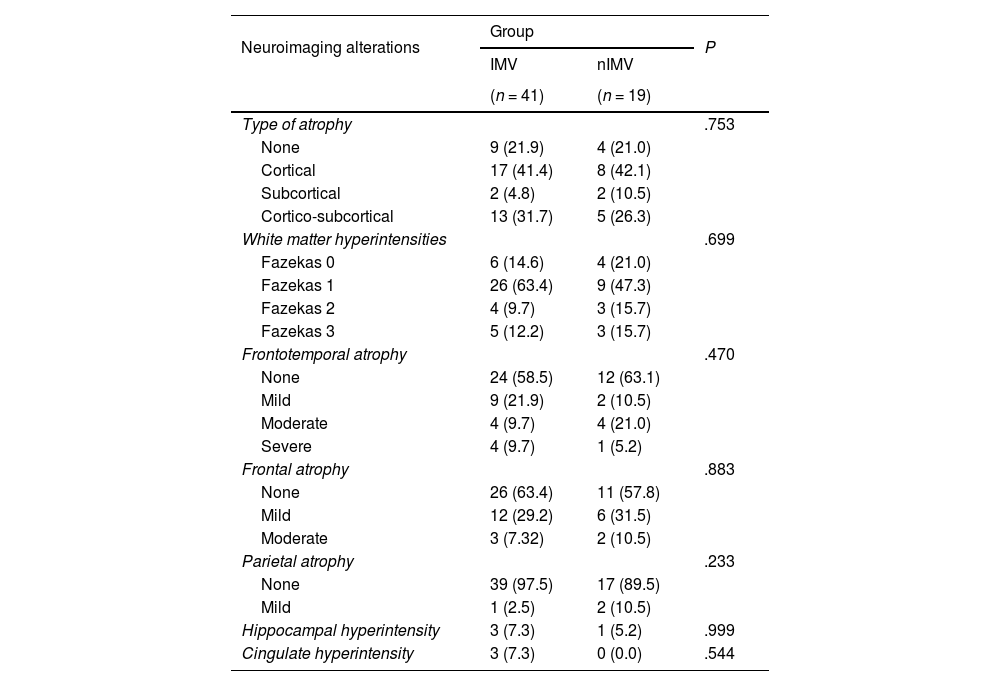

Table 4 shows the findings of the MRI studies. We observed hyperintense lesions in subcortical white matter classified as Fazekas 1 in 35 patients: 63.4% of the IMV group and 47.3% of the nIMV group; Fazekas 2 in 9.7% of patients in the IMV group and 15.7% in the nIMV group; and Fazekas 3 in 15.7% of patients in the nIMV group and 12.2% in the IMV group. We should underscore that no significant differences were observed in the comparison between groups.

Comparison between groups according to the type of neuroimaging alteration.

| Neuroimaging alterations | Group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMV | nIMV | ||

| (n = 41) | (n = 19) | ||

| Type of atrophy | .753 | ||

| None | 9 (21.9) | 4 (21.0) | |

| Cortical | 17 (41.4) | 8 (42.1) | |

| Subcortical | 2 (4.8) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Cortico-subcortical | 13 (31.7) | 5 (26.3) | |

| White matter hyperintensities | .699 | ||

| Fazekas 0 | 6 (14.6) | 4 (21.0) | |

| Fazekas 1 | 26 (63.4) | 9 (47.3) | |

| Fazekas 2 | 4 (9.7) | 3 (15.7) | |

| Fazekas 3 | 5 (12.2) | 3 (15.7) | |

| Frontotemporal atrophy | .470 | ||

| None | 24 (58.5) | 12 (63.1) | |

| Mild | 9 (21.9) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Moderate | 4 (9.7) | 4 (21.0) | |

| Severe | 4 (9.7) | 1 (5.2) | |

| Frontal atrophy | .883 | ||

| None | 26 (63.4) | 11 (57.8) | |

| Mild | 12 (29.2) | 6 (31.5) | |

| Moderate | 3 (7.32) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Parietal atrophy | .233 | ||

| None | 39 (97.5) | 17 (89.5) | |

| Mild | 1 (2.5) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Hippocampal hyperintensity | 3 (7.3) | 1 (5.2) | .999 |

| Cingulate hyperintensity | 3 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) | .544 |

IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; nIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation.

Data are expressed as number and percentage.

The type of atrophy most frequently observed was cortical, present in 25 patients (41.4% in the IMV group vs 42.1% in the nIMV group), followed by cortico-subcortical atrophy in 18 (31.7% vs 26.3%), and subcortical atrophy in 4 (4.8% vs 10.5%).

Frontotemporal atrophy was observed in 24 patients: 17 in the IMV (41.3%) versus 7 in the nIMV group (36.7%), followed by frontal atrophy in 15 patients in the IMV group (36.5%) versus 8 patients in the nIMV group (42.0%).

We only observed hippocampal hyperintensities in 4 patients, with greater prevalence in the IMV group (7.3%) (Table 4).

Spearman rank correlationWhen comparing NPT scores and laboratory study results, we observed significant associations between glucose levels and the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) recall trial (−0.278; P = .049); and between urea levels and the Stroop interference test (0.323; P = .018), HVLT-learning trial (−0.278; P = .043), and HVLT-recall trial (−0.359; P = .008). LDH levels showed a significant association with the results in the HVLT-recall trial (−0.285; P = .043) and total Brief Test of Attention score (−0.358; P = .010) (Supplementary Table S1).

The study of the association between NPT result and neuroimaging findings revealed significant associations between the type of atrophy and verbal fluency (words beginning with F) (−0.277; P = .041) and verbal fluency (words beginning with A) (−0.315; P = .019). White matter hyperintensities were correlated with verbal fluency (words beginning with F) (0.280; P = .038) and verbal fluency (words beginning with S) (−0.329; P = .014). Parietal atrophy was correlated with the Boston Naming Test (−0.296; P = .028), Stroop colour test (−0.283; P = .036), TMT part B (−0.273; P = .044), and Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure test (recall) (−0.336; P = .012). Hippocampal hyperintensity was correlated with HVLT-learning trial results (−0.371; P = .005). Lastly, cingulate hyperintensity was correlated with HVLT-learning trial results (−0.308; P = .022) (Supplementary Table S2).

Regarding the correlation between NPT results and neuropsychiatric symptoms, we observed significant associations between MFE scale results and low scores for executive functions (0.319; P = .035). PHQ-9 results showed a significant association with the results in the Stroop interference test (−0.315; P = .018) and the digit span backwards test (−0.331; P = .013) (Supplementary Table S3).

The associations observed between neuropsychological evaluation results and laboratory, imaging, and neuropsychiatric findings are significant but weak; all associations observed are shown in the Supplementary material (Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

Partial correlation between cognitive and imaging findingsA significant, inverse association was observed between parietal atrophy and results in the Boston Naming Test (−0.287; P = .035) and Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure test (recall) (−0.324; P = .017), and between frontal atrophy and phonological verbal fluency (−0.276; P = .042). The HVLT-learning trial was associated with hippocampal (−0.266; P = .050) and cingulate hyperintensity (0.311; P = .021). Results on the TMT part B were directly associated with white matter hyperintensity (0.345; P = .010).

Comparison with functional statusFunctional status was assessed with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), with scores > 3 indicating poor functional prognosis. As shown in Table 2, 27.1% of the total sample had poor functional prognosis: 35% in the IMV group vs 10.5% in the nIMV group.

Poor functional prognosis was correlated with anxiety (P < .001), depression (P < .001), high D-dimer levels (P = .002), and higher number of intubated days (P = .005).

Other variables associated with poor functional prognosis in patients requiring IMV were pneumonia persisting at 3 months and critical illness neuropathy (P = .030). We observed no correlations between functional status (mRS score) and cognitive test performance.

DiscussionThis is a pioneering study in Mexico that represents the first 2 waves of COVID-19 in patients with moderate to severe symptoms, who underwent a neurological clinical assessment, neuropsychological evaluation, and MRI study at 3 months after hospital discharge.

Several studies have addressed the association between cognitive symptoms and brain lesions; however, few studies have been performed in hospitalised patients with long COVID.10 This is one of the few studies that describe the association between cognitive alterations and brain lesions in patients with long COVID who required hospitalisation and mechanical ventilation, whether invasive or non-invasive.

According to MoCA results, 66% of the assessed patients presented post-COVID-19 cognitive symptoms, which is consistent with studies reporting that a high percentage of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (70%–100%) present cognitive deficits at discharge, which persist in the long term in up to 50% of cases.39,40

Considering the findings of the exhaustive cognitive assessment, 85% of patients obtained scores below the population average, according to normative data, in at least one test, mainly in those assessing attention and executive processes. These findings are similar to those described by Voruz et al.,41 who reported that moderate and severe forms of COVID-19 caused greater neuropsychological deficits in the long term than those observed in a normative population. This supports the hypothesis that COVID-19 has long-term effects on cognitive function, independently of the severity of the initial infection.

As mentioned previously, all patients included in our study presented moderate to severe symptoms, were hospitalised, and required mechanical ventilation. However, although our study does not include a group with mild symptoms, cognitive symptoms in long COVID are confirmed at 3 months after hospital discharge. A poorer cognitive profile has been reported in hospitalised patients than in non-hospitalised patients, characterised by alterations in attention and working memory, information processing speed, memory, language, and visuospatial abilities.10 Badenoch et al.42 report cognitive impairment, anxiety, post-traumatic symptoms, and depression as frequent symptoms in the first 6 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. It has been suggested that alterations in patients with long COVID are characterised by a dynamic,10 multifactorial40 process, which may mediate symptom severity.

In our cohort, 35% of patients scored below the mean in at least 3 of the executive function tasks. Mazza et al.43 identified executive function alterations in half of their patients with long COVID at 3 months after the hospitalisation: 30% performed poorly in tests assessing information processing, verbal fluency, and working memory. Almeria et al.8 reported frequent neurological manifestations in patients with long COVID, including cognitive impairment, with patients presenting low scores on memory, attention, and executive function tests; this is consistent with our results, as in addition to identifying executive function alterations, we also observed alterations in tasks assessing such areas as memory (HVLT) and attention (TMT parts A and B).

Cognitive alterations in our population showed no association with clinical factors or laboratory biomarkers, and the significant correlations observed were weak. Similarly, García-Sánchez et al.44 reported that the attention and executive deficits identified in patients with subjective cognitive complaints after COVID-19 were largely unrelated to such clinical factors as hospitalisation, disease duration, biomarkers, or affective factors.45

Few studies have compared cognitive symptoms in patients who required IMV vs those who required nIMV; the study performed by Alemanno et al.46 reported that patients who required IMV presented higher scores in MoCA subtests assessing visuospatial functions, executive functions, short-term memory, abstraction, and orientation. Similarly to that study, we observed that patients in the IMV group showed better performance in the MoCA test than those in the nIMV group. As mentioned by Alemanno et al.,46 these data are surprising, as they show that patients undergoing invasive ventilation, that is, patients in a more critical state, showed better preserved cognitive status. However, more targeted assessment of cognitive impairment, through an extensive evaluation and specific tests for each function, revealed no significant differences in NPT performance between groups. We should mention that these authors performed no NPTs targeted at assessing the different domains specifically.

Other Latin American studies have focused on assessing cognitive symptoms in long COVID. The cohort study by Del Brutto et al.47 compared pre- and post-pandemic cognitive performance in patients seropositive and seronegative for SARS-CoV-2, with 20% of seropositive patients reporting cognitive impairment versus 2% of seronegative patients. In this case, the evaluation consisted of the MoCA, and not specific NPTs to assess the different cognitive functions.

Regarding MFE scale results, we observed higher scores in the nIMV group than in the IMV group. This finding may be related to the awareness of patients in the nIMV group of their situation during their hospitalisation, in comparison with patients who required IMV, who were sedated and thus avoided the stress associated with this situation. These findings are consistent with reports in the literature, with similar data between groups.48 Maydych49 suggests that acute and chronic stress is associated with an increase in inflammatory mechanisms and increased attention processing of negative information. Both phenomena are predictive of depressive symptoms, which, in turn, increase inflammatory and cognitive reactivity to stress.

In terms of imaging results, we observed white matter hyperintensities, as well as brain atrophy, which is very similar to the findings documented in other studies comparing patients with long COVID against controls.50

An association has been described between impaired executive function, language, and information processing speed and WMLs in different brain regions, such as the superior frontal region, postcentral region, cingulate, corticospinal tract, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, internal capsule, and posterior segment of the right arcuate fasciculus.6

Similarly, we observed correlations between brain atrophy and cognitive functions, between frontal atrophy and executive functions (phonological verbal fluency), between parietal atrophy and visual agnosia and memory test performance, and between hippocampal and cingulate hyperintensities and the test assessing learning. White matter hyperintensity was associated with attention tests performance. Similarly, the study by Douaud et al.51 reported a higher degree of volume loss in hospitalised patients, especially frontoparietal and temporal atrophy, as well as errors in the tests assessing executive function and attention. Díez-Cirarda et al.10 published another study supporting our results, which reported that hippocampal, subtemporal, and anterior cerebellar volume loss were associated with deficits on tests assessing memory, attention, and processing speed.

It is relevant to underscore that, when comparing between groups according to the type of mechanical ventilation, we observed no significant differences in the cognitive profile and MRI findings. The impairment of different regions and functions shown in this study and several of the other studies cited suggests that multiple systems and mechanisms are involved in the generation of the cognitive deficit.10

The majority of series of cases of cognitive symptoms in long COVID reported to date use different cognitive assessment tools, ranging from surveys to telephone assessments, which makes it difficult to determine the true prevalence of cognitive impairment after COVID-19 in this population. It is important to underscore our use of a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, which enables us to identify the cognitive profiles of patients and describe long COVID symptoms, as this is relevant for identifying the subsequent development of increased cognitive impairment. One possible phenomenon involved is neurodegeneration as a chronic inflammatory status, caused by the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 infection may accelerate or trigger the development of neurodegenerative diseases in the future; this hypothesis is still to be confirmed.

Our study presents certain limitations. The first is the limited sample size, including only a small number of patients requiring hospitalisation; in other words, we included no patients with mild infection nor a control group. The second limitation is the fact that participants were recruited at a tertiary hospital, which was the main reference centre for patients with severe disease during the pandemic in Mexico City; therefore, we had difficulty accessing patients with mild symptoms, which would have enabled us to perform a different analysis according to the severity of the disease. As a third limitation, we should mention that delirium is more frequent in patients requiring IMV and that its origin is multifactorial; however, we did not analyse the remaining factors influencing the presence of delirium.

This study is based on a structured, face-to-face assessment with a complete neurological examination, including laboratory studies, a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment with tests validated in our country, and neurological function and neuropsychiatric scales, which contributes to a systematic search for residual objective anomalies after COVID-19.

ConclusionOur study suggests the presence of cognitive alterations 3 months after hospital discharge, particularly affecting executive, attention, and memory functions, in patients who presented moderate-severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. We observed WMLs and brain atrophy in frontal and parietal regions, which are associated with cognitive impairment. These results are not affected by whether patients required IMV or nIMV.

Our findings highlight the clinical need for longitudinal programmes able to assess the real impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the central nervous system, manifesting in the cognitive and emotional areas.

FundingThis study has received no funding from any public, private, or non-profit organisation.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.