It was with great interest that we read the article “Spinal arteriovenous fistulas in adults: management of a series of patients treated at a neurology department” by Ortega-Suero et al.1 In this study, the authors retrospectively analyse the outcomes in a series of 10 patients with spinal arteriovenous fistulas (AVF) treated at their hospital over a 3-year period. Firstly, we wish to congratulate the authors on their series, the second modern series of patients with spinal AVFs to be published in Spain.1,2 Ortega-Suero et al.1 include 6 cases of spinal dural AVFs; we will focus on this type of AVF since they represent 75% of all spinal vascular malformations. We agree that spinal dural AVFs are difficult to diagnose despite considerable advances in neuroimaging techniques. Though rare, this type of AVF should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with symptoms of progressive myelopathy and/or radiculopathy, given the poor neurological outcomes associated with late diagnosis and treatment. Up to 25%-30% of patients present paraplegia by the time spinal dural AVF is diagnosed.3 Furthermore, a considerable percentage of patients will already have undergone unnecessary spine surgery following incorrect aetiological diagnosis of their neurological symptoms, which are often attributed to spinal canal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, or disc herniation.4,5 The optimal treatment for spinal dural AVFs is also controversial, with either endovascular therapy or surgery constituting the treatment of choice. The purpose of this letter is to comment on 2 fundamental aspects of treatment for spinal dural AVFs: 1) patients may present rapidly progressive neurological deterioration; in these cases, early occlusion of the fistula should be considered even if the patient already presents paraplegia (neurological improvement has been reported in most cases of early treatment); and 2) analysis of recent case series shows that, despite continuous improvements, endovascular treatment continues to be less effective than surgery; the latter achieves higher rates of complete dural AVF occlusion and is associated with a low morbidity rate.

Patients with spinal dural AVFs may display severe, rapidly progressive neurological deterioration characterised by lower limb paralysis and sphincter dysfunction, known as Foix-Alajouanine syndrome; the pathophysiology is yet to be fully understood.3 The syndrome has traditionally been thought to be caused by irreversible necrotising myelopathy secondary to venous thrombosis. The high rates of improvement following treatment for spinal dural AVFs, even in patients with complete paraplegia, demonstrate that functional spinal cord alterations underlying severe neurological impairment may be due to decreased nervous tissue perfusion secondary to venous hypertension.3,5,6 Severe, prolonged reduction of spinal cord perfusion pressure may lead to spinal cord infarction, which may explain why symptom duration, rather than the degree of neurological impairment at diagnosis, is the main prognostic factor in spinal dural AVFs.3,4,7 Eight years ago, our research group published a study of the prognosis of 107 patients with spinal dural AVFs and paraplegia at the time of treatment. Symptoms improved after treatment in approximately 75% of patients. However, improvements were limited in most cases, with fewer than 6% of patients being able to walk without assistance.3 Lack of complete recovery in most of these patients was most likely due to diagnostic delays: mean time from symptom onset to definitive diagnosis was 20 months.3 In our study, paraplegia duration was less than 24hours in approximately two-thirds of patients with paraplegia secondary to a spinal dural AVF and showing neurological improvement (from an Aminoff-Logue scale score for gait disturbance of 5 [wheelchair-bound] to 1 [leg weakness but no restriction of activity]) after treatment. In the remaining patients displaying such a marked clinical improvement, the mean time of progression of neurological deficits was shorter than 2 months.3 According to other series, patients with longer symptom progression times are less likely to display significant improvements after surgery.4,7 Spinal dural AVFs should therefore be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with rapidly progressive lower limb weakness, paraesthesia, and/or sphincter dysfunction of undetermined origin, particularly in elderly patients displaying unusually fast symptom progression.

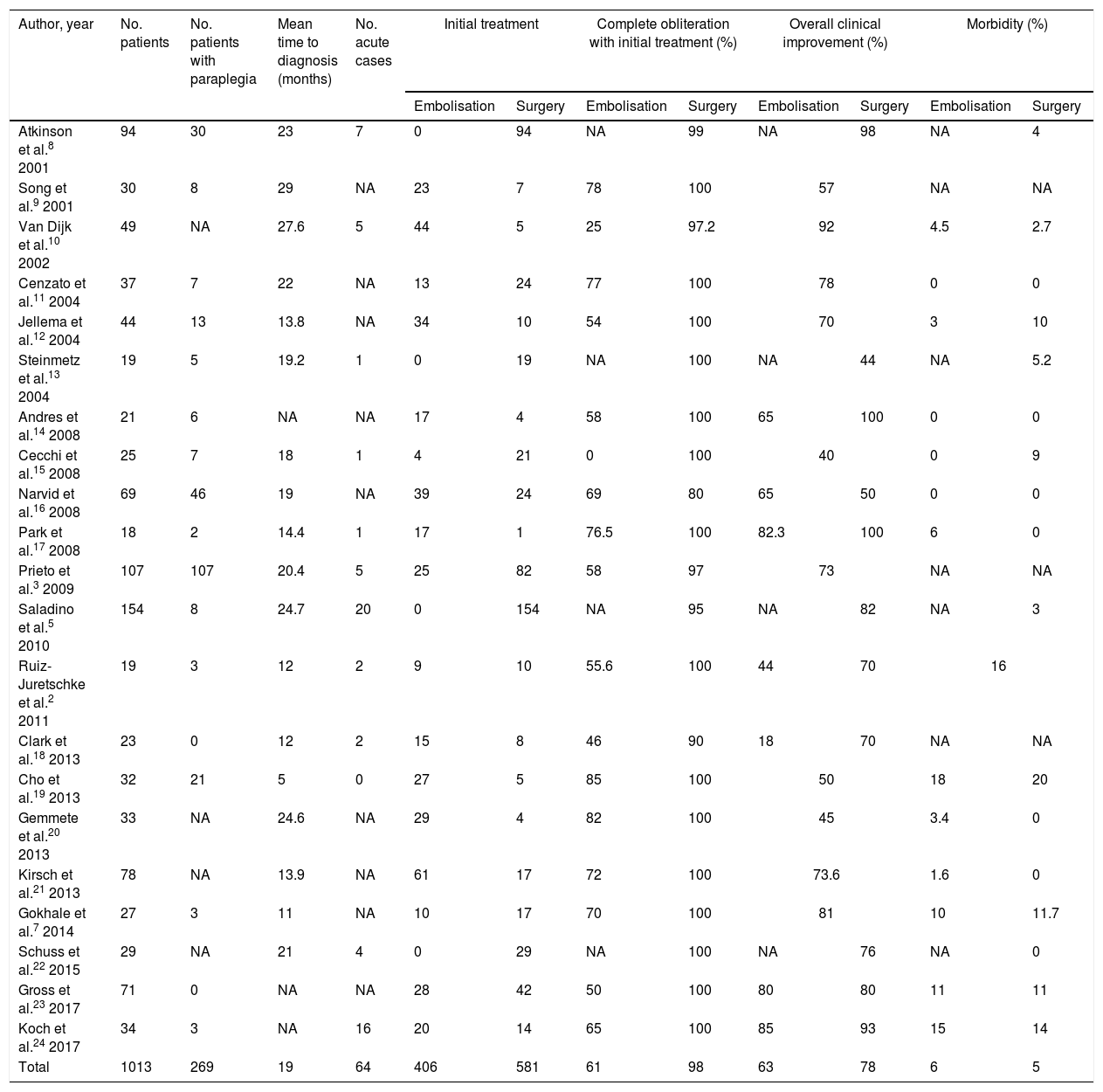

Regarding the optimal treatment for spinal dural AVFs, advances in embolisation techniques, with the use of liquid agents that can be introduced into the draining vein, enable treatment of the fistula during diagnostic arteriography, and have led to increases in the rate of endovascular treatment in many centres. Training for young neurosurgeons in cerebrovascular disease and spinal vascular malformations is currently lacking; in Spain, this has led to a predominance of endovascular treatment over surgery, as demonstrated by the series of patients treated between 2012 and 2015 published by Ortega-Suero et al.1 However, recent case series of spinal dural AVFs published by the most relevant international research groups show that surgery was the initial treatment for occlusion of the fistula in nearly 60% of patients (Table 1).2,3,5,7–24 Despite the heterogeneity of these series, all show better angiographic and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing surgery than in those undergoing endovascular treatment. The percentage of complete, permanent obliteration of the spinal dural AVF in a single procedure was nearly 100% among patients undergoing surgery, compared to 61% in patients receiving endovascular treatment. Differences in clinical outcomes were more marked: nearly 80% of surgery patients presented clinical improvements, compared to only 63% of those undergoing endovascular treatment. Furthermore, some series report poorer clinical prognosis in patients undergoing surgery following failure of endovascular treatment, whether due to incomplete occlusion of the fistula or to recanalisation.14,18

Series of patients with spinal dural arteriovenous fistulas published in the past 20 years.a

| Author, year | No. patients | No. patients with paraplegia | Mean time to diagnosis (months) | No. acute cases | Initial treatment | Complete obliteration with initial treatment (%) | Overall clinical improvement (%) | Morbidity (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embolisation | Surgery | Embolisation | Surgery | Embolisation | Surgery | Embolisation | Surgery | |||||

| Atkinson et al.8 2001 | 94 | 30 | 23 | 7 | 0 | 94 | NA | 99 | NA | 98 | NA | 4 |

| Song et al.9 2001 | 30 | 8 | 29 | NA | 23 | 7 | 78 | 100 | 57 | NA | NA | |

| Van Dijk et al.10 2002 | 49 | NA | 27.6 | 5 | 44 | 5 | 25 | 97.2 | 92 | 4.5 | 2.7 | |

| Cenzato et al.11 2004 | 37 | 7 | 22 | NA | 13 | 24 | 77 | 100 | 78 | 0 | 0 | |

| Jellema et al.12 2004 | 44 | 13 | 13.8 | NA | 34 | 10 | 54 | 100 | 70 | 3 | 10 | |

| Steinmetz et al.13 2004 | 19 | 5 | 19.2 | 1 | 0 | 19 | NA | 100 | NA | 44 | NA | 5.2 |

| Andres et al.14 2008 | 21 | 6 | NA | NA | 17 | 4 | 58 | 100 | 65 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Cecchi et al.15 2008 | 25 | 7 | 18 | 1 | 4 | 21 | 0 | 100 | 40 | 0 | 9 | |

| Narvid et al.16 2008 | 69 | 46 | 19 | NA | 39 | 24 | 69 | 80 | 65 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Park et al.17 2008 | 18 | 2 | 14.4 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 76.5 | 100 | 82.3 | 100 | 6 | 0 |

| Prieto et al.3 2009 | 107 | 107 | 20.4 | 5 | 25 | 82 | 58 | 97 | 73 | NA | NA | |

| Saladino et al.5 2010 | 154 | 8 | 24.7 | 20 | 0 | 154 | NA | 95 | NA | 82 | NA | 3 |

| Ruiz-Juretschke et al.2 2011 | 19 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 9 | 10 | 55.6 | 100 | 44 | 70 | 16 | |

| Clark et al.18 2013 | 23 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 15 | 8 | 46 | 90 | 18 | 70 | NA | NA |

| Cho et al.19 2013 | 32 | 21 | 5 | 0 | 27 | 5 | 85 | 100 | 50 | 18 | 20 | |

| Gemmete et al.20 2013 | 33 | NA | 24.6 | NA | 29 | 4 | 82 | 100 | 45 | 3.4 | 0 | |

| Kirsch et al.21 2013 | 78 | NA | 13.9 | NA | 61 | 17 | 72 | 100 | 73.6 | 1.6 | 0 | |

| Gokhale et al.7 2014 | 27 | 3 | 11 | NA | 10 | 17 | 70 | 100 | 81 | 10 | 11.7 | |

| Schuss et al.22 2015 | 29 | NA | 21 | 4 | 0 | 29 | NA | 100 | NA | 76 | NA | 0 |

| Gross et al.23 2017 | 71 | 0 | NA | NA | 28 | 42 | 50 | 100 | 80 | 80 | 11 | 11 |

| Koch et al.24 2017 | 34 | 3 | NA | 16 | 20 | 14 | 65 | 100 | 85 | 93 | 15 | 14 |

| Total | 1013 | 269 | 19 | 64 | 406 | 581 | 61 | 98 | 63 | 78 | 6 | 5 |

NA: not available.

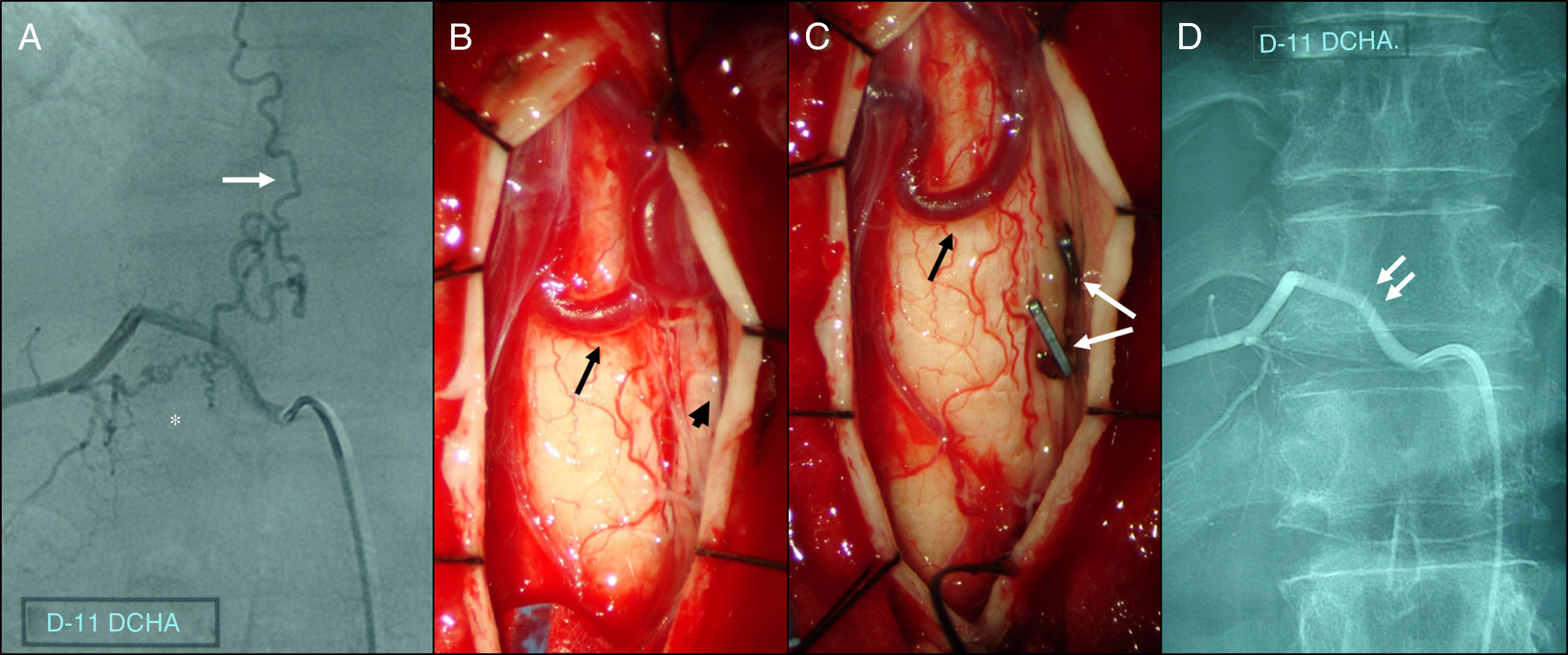

Microsurgical occlusion of spinal dural AVFs is associated with a morbidity rate of approximately 5%, similarly to that observed for endovascular treatment. However, embolisation is associated with more severe complications, which often irreversibly affect neurological function. Introducing embolic material through a catheter should not be considered non-invasive, since it is associated with a considerable risk of migration of embolic material into the venous system and/or radicular artery rupture, potentially leading to such severe outcomes as spinal cord infarction, causing permanent, irreversible motor function loss in the areas supplied by nerves emerging from below the level of the infarction.7,19,21,23 Furthermore, patients undergoing embolisation are exposed to a radiation dose above 5Gy.24 In contrast, the most frequent complications of surgery include cerebrospinal fluid fistulas and pseudomeningocele, which are never associated with permanent neurological deficits. Surgical treatment of spinal dural AVFs consists of disconnection between the dural artery and the intradural draining vein; this technique is relatively easy to perform when the lesion has been correctly diagnosed and located intraoperatively (Fig. 1). The main technical difficulties for less experienced surgeons are determining the precise location of the lesion during the procedure and confirming complete occlusion of the fistula. Both problems have partially been solved with the introduction of indocyanine green, a fluorescent contrast agent enabling the differentiation of arterial from venous blood flow in spinal dural AVFs. Based on the above, we may conclude that microsurgical occlusion of the fistula continues to be the safest and most effective treatment for spinal dural AVFs, regardless of recent advances in endovascular treatment, and should therefore be considered the first-line treatment for these patients. Embolisation should be considered in patients with severe comorbidities contraindicating surgery.

Spinal angiography and intraoperative photographs of a spinal dural arteriovenous fistula affecting the right radicular artery at the level of T11. (A) Selective angiography showing a fistula below the right pedicle of T11 (asterisk), connecting the radiculomeningeal artery and a varicose perimedullary vein (white arrow). (B) Intraoperative photograph following T11 laminectomy and durotomy, showing arterialisation of tortuous perimedullary veins (black arrow), in close contact with the nerve root (black arrowhead). (C) Clipping (white arrows), coagulation, and excision of the draining vein at the level of the nerve root results in immediate collapse and darkening of perimedullary veins (black arrow). (D) Postoperative spinal angiography showing complete occlusion of the fistula; the arrows indicate the vascular clips.

Please cite this article as: Prieto R, Pascual JM, Barrios L. Fístulas arteriovenosas espinales durales: ¿tratamiento precoz endovascular o quirúrgico?. Neurología. 2019;34:557–560.