Stroke is the leading cause of acquired disability in adults and the second leading cause of death. The SEGUICTUS project was carried out with the aim of knowing its clinical management in different hospitals in Spain, in order to promote corrective measures to reduce its incidence and derived consequences.

MethodsThis cross-sectional multicenter research was carried out through a survey of 40 questions on opinion, attitude and behavior. The survey was answered by 205 neurology specialists from different regions of Spain.

ResultsThe availability of resources for stroke management was statistically lower in tertiary and regional hospitals. 36.6% of the participants assessed the presence of cognitive impairment in more than half of the patients, and 37.6% used specific questionnaires to assess cognitive impairment in less than 10% of the patients. The best considered therapeutic options for its treatment were acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and citylcholine. Statistically significant differences were observed in the percentage of participants who began rehabilitation treatment during admission, being lower in tertiary hospitals.

ConclusionsThe shortage of stroke units, protocols and specialised consultations for the care of stroke patients may have an impact on the treatment of potential sequelae of stroke, such as cognitive impairment and motor sequelae. It is necessary to evaluate the deficit points in stroke management and implement the appropriate corrective measures.

El ictus constituye la primera causa de discapacidad adquirida en adultos y la segunda causa de muerte. El proyecto SEGUICTUS se realizó con el objetivo de conocer su manejo clínico en diferentes hospitales de España, como información esencial para la optimización y mejora de su atención en nuestro entorno.

MétodoInvestigación sociosanitaria transversal multicéntrica de ámbito nacional realizada mediante una encuesta de 40 preguntas sobre opinión, actitud y comportamiento. La encuesta fue respondida por 205 especialistas en neurología de diferentes regiones de España.

ResultadosLa disponibilidad de recursos para el manejo del ictus fue estadísticamente menor en los hospitales terciarios y comarcales. El 36,6% de los participantes valoraban la existencia de deterioro cognitivo en más de la mitad de los pacientes, y el 37,6% utilizaba cuestionarios específicos para evaluar el deterioro cognitivo en menos del 10% de pacientes. Se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el porcentaje de participantes que iniciaban tratamiento rehabilitador durante el ingreso, en la revisión de los valores de INR, y en la inclusión de escalas funcionales específicas en los informes de alta o seguimiento, siendo menor en los hospitales terciarios.

ConclusionesLa escasez de unidades de ictus, protocolos y consultas monográficas para la atención de los pacientes con ictus puede tener un impacto en el tratamiento de las potenciales secuelas del ictus, como es el caso del deterioro cognitivo y las secuelas motoras. Es necesario evaluar los puntos deficitarios en el manejo del ictus e implementar las medidas correctoras adecuadas.

In Spain, stroke is a major public health issue that poses constant challenges in terms of care and follow-up. According to a national registry published in 2012, the crude annual incidence of all cerebrovascular events in 2006 was 187 cases per 100 000 population.1 Recent estimates point to a 35% increase in incidence rates between 2015 and 2035, which is largely attributed to the increase in life expectancy.2 Stroke is the leading cause of acquired disability in adults,3 as well as the second leading cause of death, after ischaemic heart disease, causing approximately 27 000 deaths per year.4 The annual cost per patient attended at a stroke unit exceeds €27 000, with the majority of this cost corresponding to social costs.5

Stroke units constitute the most effective resource for acute stroke management, significantly reducing mortality and dependence.6 These units should be formed by multidisciplinary teams exclusively dedicated to the care of patients with acute stroke based on the best available evidence.7 Current clinical guidelines recommend that all patients with stroke be managed at stroke units.8–11

In Spanish local hospitals, stroke teams have emerged as an alternative to stroke units, with a view to optimising healthcare resources.7 Although these teams include physicians from the emergency and intensive care departments, who are able to treat stroke in the acute stage and administer effective emergency treatment, they lack neurology specialists. Code stroke is another necessary mechanism for the proper management of acute stroke, decreasing the delay between symptom onset and treatment initiation in eligible patients, ultimately improving clinical outcomes.12–14

Health surveys targeted at healthcare professionals contribute to improving care quality, and represent an essential tool for healthcare planning. The SEGUICTUS project is based on a questionnaire administered to specialists in neurology and primary care, aiming to gather their opinions and thoughts on stroke care in Spain. A secondary objective was to promote certain corrective measures to reduce the incidence of stroke and to minimise its consequences. This study presents a summary of the responses reported by neurology specialists.

MethodsThe SEGUICTUS project is a nationwide, multicentre, cross-sectional study. A scientific committee designed a questionnaire addressing healthcare professionals’ opinions, attitudes, and behaviours regarding the management of stroke and its most frequent complications in Spain, with a view to collecting qualitative data that is representative of real-world clinical practice.

The sample size was calculated using a 95% confidence interval for a finite population proportion; the final sample size achieved 5% precision for a 95% confidence level. Based on a reference population of 46 934 628, a representative sample was estimated to include 225 neurology specialists and 309 primary care physicians from across Spain. Participants were selected through non-probabilistic quota sampling, establishing proportional quotas based on population criteria and the number of healthcare centres per autonomous community. They were contacted with an information leaflet and completed the online survey between November 2020 and March 2021. This study summarises the responses of neurology specialists.

We conducted a descriptive analysis using measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation [SD] or minimum and maximum values) for quantitative variables, and frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. We used the Fisher exact test for an mxn contingency table to determine statistically significant differences between the different types of healthcare centres to which participants belonged. The chi-square test was used when convergence was not achieved.

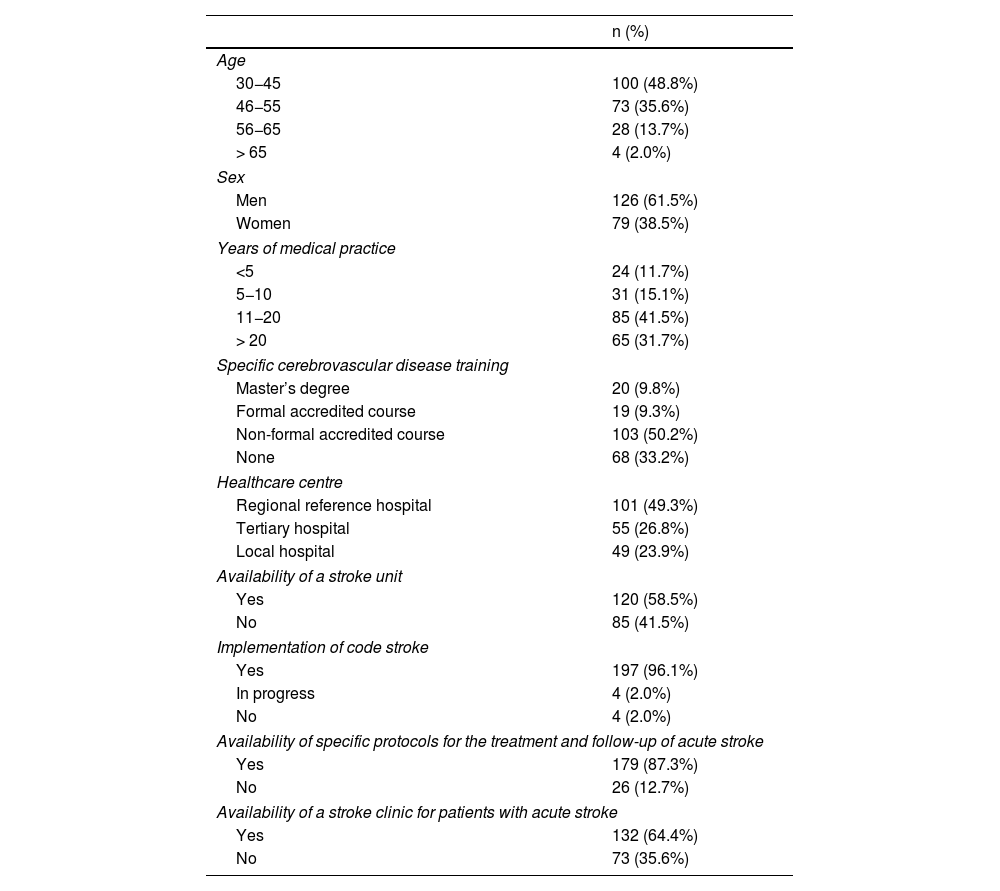

ResultsParticipant characteristics and resources availableA total of 205 neurology specialists completed the survey, 61.5% of whom were men. Regarding age, 48.0% of participants were 30−45 years old and 35.6% were 46–65 years old. Participants had practised medicine for a mean (SD) of 16.8 (9.5) years, and 19.1% had received specific training in cerebrovascular disease through accredited courses or master’s degrees (Table 1).

Participant characteristics and resources available (N = 205).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 30−45 | 100 (48.8%) |

| 46−55 | 73 (35.6%) |

| 56−65 | 28 (13.7%) |

| > 65 | 4 (2.0%) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 126 (61.5%) |

| Women | 79 (38.5%) |

| Years of medical practice | |

| <5 | 24 (11.7%) |

| 5−10 | 31 (15.1%) |

| 11−20 | 85 (41.5%) |

| > 20 | 65 (31.7%) |

| Specific cerebrovascular disease training | |

| Master’s degree | 20 (9.8%) |

| Formal accredited course | 19 (9.3%) |

| Non-formal accredited course | 103 (50.2%) |

| None | 68 (33.2%) |

| Healthcare centre | |

| Regional reference hospital | 101 (49.3%) |

| Tertiary hospital | 55 (26.8%) |

| Local hospital | 49 (23.9%) |

| Availability of a stroke unit | |

| Yes | 120 (58.5%) |

| No | 85 (41.5%) |

| Implementation of code stroke | |

| Yes | 197 (96.1%) |

| In progress | 4 (2.0%) |

| No | 4 (2.0%) |

| Availability of specific protocols for the treatment and follow-up of acute stroke | |

| Yes | 179 (87.3%) |

| No | 26 (12.7%) |

| Availability of a stroke clinic for patients with acute stroke | |

| Yes | 132 (64.4%) |

| No | 73 (35.6%) |

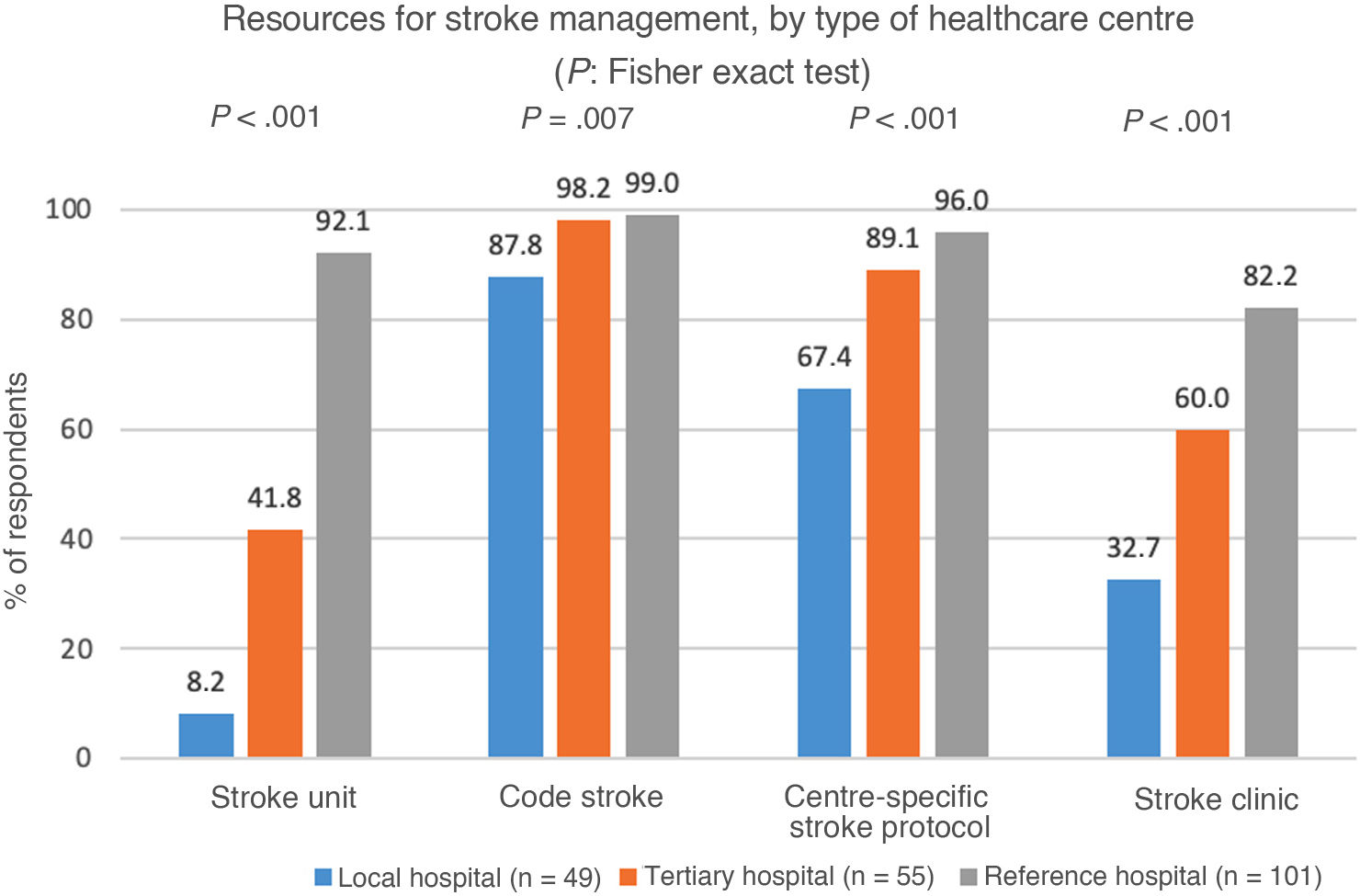

A total of 49.5% of participants worked at provincial reference hospitals, 26.8% at tertiary hospitals, and 23.9% at local hospitals. Regarding available resources, 58.5% reported the presence of a stroke unit at their hospital, 64.4% reported a dedicated stroke clinic, and 87.3% reported the use of a centre-specific stroke protocol. Furthermore, 96.1% reported that code stroke had been implemented at their centre (Table 1). Statistically significant differences were observed in the availability of resources between hospitals (Fig. 1). For example, 92.1% of participants working at reference hospitals reported availability of a stroke unit, compared to only 41.8% and 8.2% of the participants working at tertiary hospitals and local hospitals, respectively.

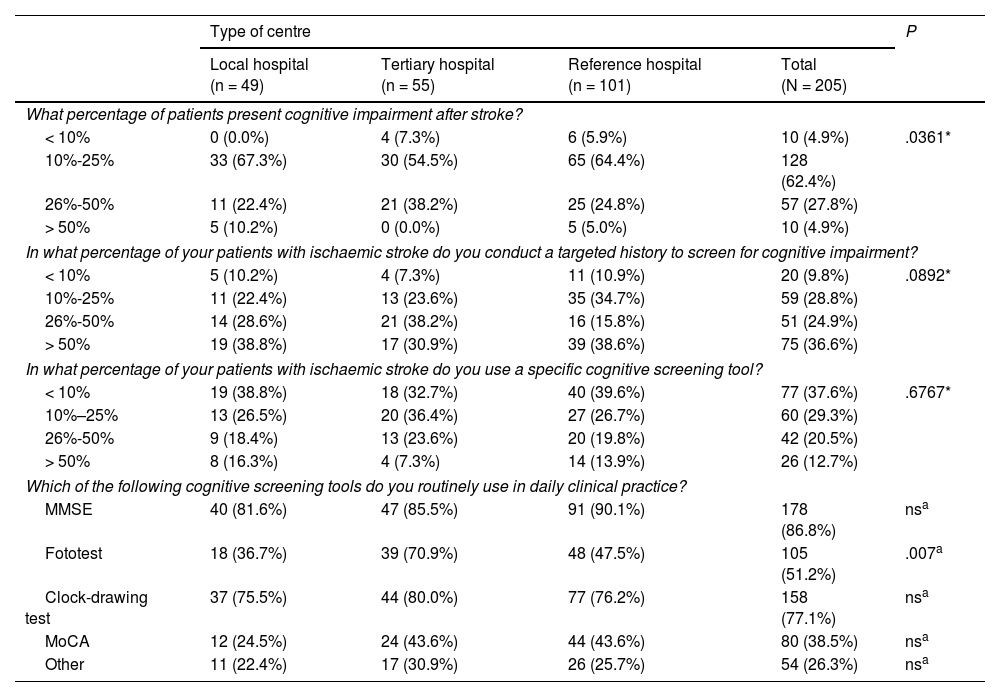

Assessment and treatment of patients with strokeCognitive impairmentA total of 90.2% of participants reported that 10%–50% of their patients presented cognitive impairment as a sequela of stroke (worsening of pre-existing cognitive impairment was not assessed). Statistically significant differences were found between centres, particularly between tertiary hospitals and other types of centres. A total of 36.6% of participants reported that they routinely assessed cognitive impairment during history taking in more than half of their patients, with no differences between types of healthcare centres (Table 2).

Assessment of cognitive impairment.

| Type of centre | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local hospital (n = 49) | Tertiary hospital (n = 55) | Reference hospital (n = 101) | Total (N = 205) | ||

| What percentage of patients present cognitive impairment after stroke? | |||||

| < 10% | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (7.3%) | 6 (5.9%) | 10 (4.9%) | .0361* |

| 10%-25% | 33 (67.3%) | 30 (54.5%) | 65 (64.4%) | 128 (62.4%) | |

| 26%-50% | 11 (22.4%) | 21 (38.2%) | 25 (24.8%) | 57 (27.8%) | |

| > 50% | 5 (10.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (5.0%) | 10 (4.9%) | |

| In what percentage of your patients with ischaemic stroke do you conduct a targeted history to screen for cognitive impairment? | |||||

| < 10% | 5 (10.2%) | 4 (7.3%) | 11 (10.9%) | 20 (9.8%) | .0892* |

| 10%-25% | 11 (22.4%) | 13 (23.6%) | 35 (34.7%) | 59 (28.8%) | |

| 26%-50% | 14 (28.6%) | 21 (38.2%) | 16 (15.8%) | 51 (24.9%) | |

| > 50% | 19 (38.8%) | 17 (30.9%) | 39 (38.6%) | 75 (36.6%) | |

| In what percentage of your patients with ischaemic stroke do you use a specific cognitive screening tool? | |||||

| < 10% | 19 (38.8%) | 18 (32.7%) | 40 (39.6%) | 77 (37.6%) | .6767* |

| 10%–25% | 13 (26.5%) | 20 (36.4%) | 27 (26.7%) | 60 (29.3%) | |

| 26%-50% | 9 (18.4%) | 13 (23.6%) | 20 (19.8%) | 42 (20.5%) | |

| > 50% | 8 (16.3%) | 4 (7.3%) | 14 (13.9%) | 26 (12.7%) | |

| Which of the following cognitive screening tools do you routinely use in daily clinical practice? | |||||

| MMSE | 40 (81.6%) | 47 (85.5%) | 91 (90.1%) | 178 (86.8%) | nsa |

| Fototest | 18 (36.7%) | 39 (70.9%) | 48 (47.5%) | 105 (51.2%) | .007a |

| Clock-drawing test | 37 (75.5%) | 44 (80.0%) | 77 (76.2%) | 158 (77.1%) | nsa |

| MoCA | 12 (24.5%) | 24 (43.6%) | 44 (43.6%) | 80 (38.5%) | nsa |

| Other | 11 (22.4%) | 17 (30.9%) | 26 (25.7%) | 54 (26.3%) | nsa |

MMSE: Mini–Mental State Examination; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; ns: not significant.

In our sample, 66.9% of participants reported using cognitive screening tools in 25% or fewer of their patients. The most frequently used tools were the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the clock-drawing test. Statistically significant differences in the use of the Fototest were observed between tertiary hospitals, reference hospitals, and local hospitals (Table 2).

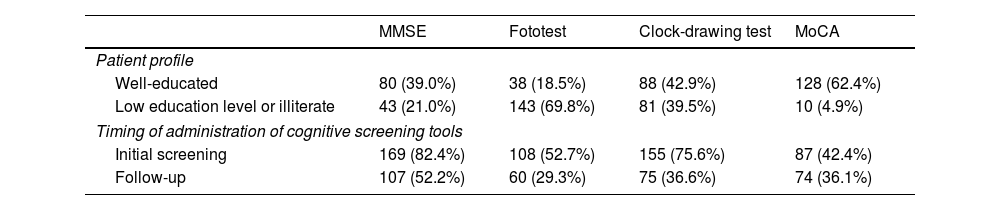

A higher percentage of participants reported using any of the 4 main cognitive screening tools (MMSE, clock-drawing test, Fototest, Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA]) for the initial assessment than for follow-up. The MMSE and the clock-drawing test were the most frequently used tools for initial screening, whereas the Fototest was the most frequently used test in illiterate individuals or those with low education level (Table 3).

Patient profile and timing of administration of cognitive screening tools (N = 205).

| MMSE | Fototest | Clock-drawing test | MoCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient profile | ||||

| Well-educated | 80 (39.0%) | 38 (18.5%) | 88 (42.9%) | 128 (62.4%) |

| Low education level or illiterate | 43 (21.0%) | 143 (69.8%) | 81 (39.5%) | 10 (4.9%) |

| Timing of administration of cognitive screening tools | ||||

| Initial screening | 169 (82.4%) | 108 (52.7%) | 155 (75.6%) | 87 (42.4%) |

| Follow-up | 107 (52.2%) | 60 (29.3%) | 75 (36.6%) | 74 (36.1%) |

MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

The survey also addressed the treatment of cognitive impairment in patients with stroke. Regarding non-pharmacological interventions, 5 options were proposed, which participants had to rank in order of use, from 1 (most used) to 5 (least used). Cognitive stimulation at home was the most frequently used approach (mean ranking of 2.1 [1.1]), followed by cognitive stimulation at a day centre (2.3 [0.9]) and cognitive stimulation at a specialised centre (2.9 [1.3]).

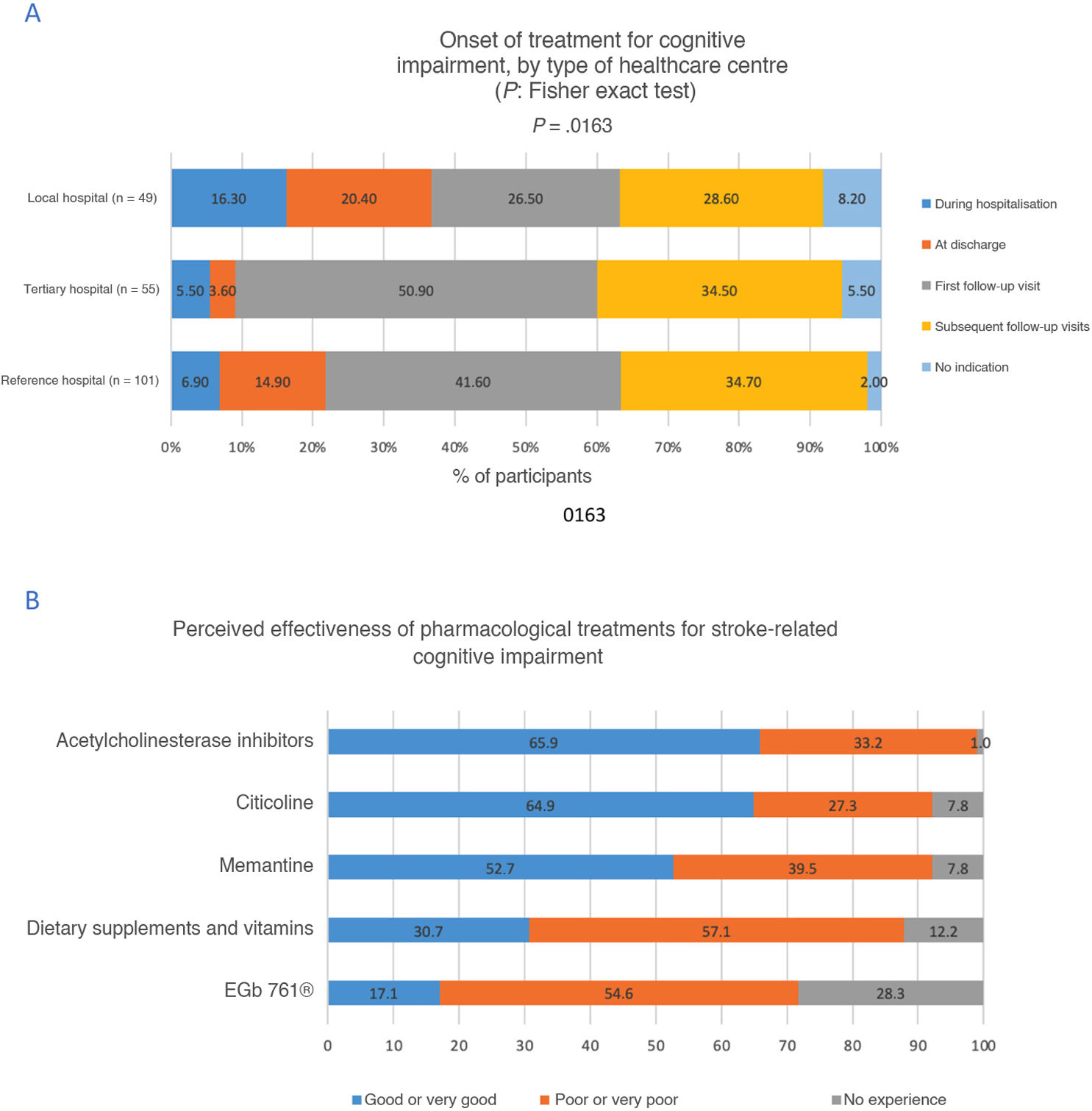

Pharmacological treatments for cognitive impairment were indicated at the first follow-up consultation by 40.5% of participants, and at hospital discharge by 13.2%. However, the latter percentage was lower at tertiary hospitals, whereas the percentage of participants who did not indicate pharmacological treatment was higher at local hospitals (P = .0163) (Fig. 2A).

Regarding the perceived effectiveness of pharmacological treatments, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors were rated as good or very good by 65.9% of participants, citicoline by 64.9%, and memantine by 52.7%. No statistically significant differences were observed between types of healthcare centre (Fig. 2B).

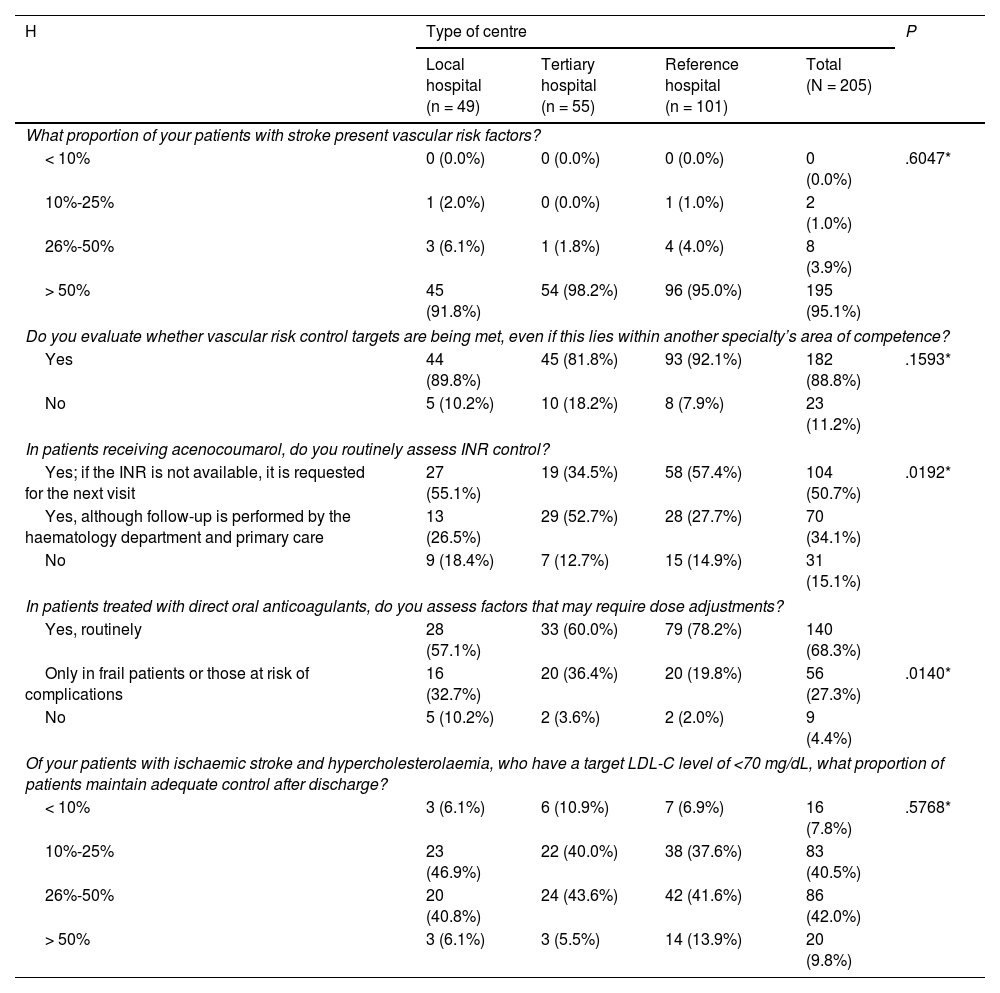

Vascular riskAccording to 95.1% of participants, most patients with stroke present vascular risk factors (VRF). Likewise, 88.8% of participants reported reviewing VRF control targets, even when this fell under another specialty, such as primary care. A total of 84.9% of participants reported routinely monitoring the international normalised ratio (INR) in patients treated with acenocoumarol; this percentage was significantly lower in tertiary hospitals. Significant differences were also observed in the percentage of participants who systematically monitored the dose of direct oral anticoagulants and the factors affecting dose adjustment (Table 4).

Vascular risk assessment.

| H | Type of centre | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local hospital (n = 49) | Tertiary hospital (n = 55) | Reference hospital (n = 101) | Total (N = 205) | ||

| What proportion of your patients with stroke present vascular risk factors? | |||||

| < 10% | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | .6047* |

| 10%-25% | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (1.0%) | |

| 26%-50% | 3 (6.1%) | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (4.0%) | 8 (3.9%) | |

| > 50% | 45 (91.8%) | 54 (98.2%) | 96 (95.0%) | 195 (95.1%) | |

| Do you evaluate whether vascular risk control targets are being met, even if this lies within another specialty’s area of competence? | |||||

| Yes | 44 (89.8%) | 45 (81.8%) | 93 (92.1%) | 182 (88.8%) | .1593* |

| No | 5 (10.2%) | 10 (18.2%) | 8 (7.9%) | 23 (11.2%) | |

| In patients receiving acenocoumarol, do you routinely assess INR control? | |||||

| Yes; if the INR is not available, it is requested for the next visit | 27 (55.1%) | 19 (34.5%) | 58 (57.4%) | 104 (50.7%) | .0192* |

| Yes, although follow-up is performed by the haematology department and primary care | 13 (26.5%) | 29 (52.7%) | 28 (27.7%) | 70 (34.1%) | |

| No | 9 (18.4%) | 7 (12.7%) | 15 (14.9%) | 31 (15.1%) | |

| In patients treated with direct oral anticoagulants, do you assess factors that may require dose adjustments? | |||||

| Yes, routinely | 28 (57.1%) | 33 (60.0%) | 79 (78.2%) | 140 (68.3%) | |

| Only in frail patients or those at risk of complications | 16 (32.7%) | 20 (36.4%) | 20 (19.8%) | 56 (27.3%) | .0140* |

| No | 5 (10.2%) | 2 (3.6%) | 2 (2.0%) | 9 (4.4%) | |

| Of your patients with ischaemic stroke and hypercholesterolaemia, who have a target LDL-C level of <70 mg/dL, what proportion of patients maintain adequate control after discharge? | |||||

| < 10% | 3 (6.1%) | 6 (10.9%) | 7 (6.9%) | 16 (7.8%) | .5768* |

| 10%-25% | 23 (46.9%) | 22 (40.0%) | 38 (37.6%) | 83 (40.5%) | |

| 26%-50% | 20 (40.8%) | 24 (43.6%) | 42 (41.6%) | 86 (42.0%) | |

| > 50% | 3 (6.1%) | 3 (5.5%) | 14 (13.9%) | 20 (9.8%) | |

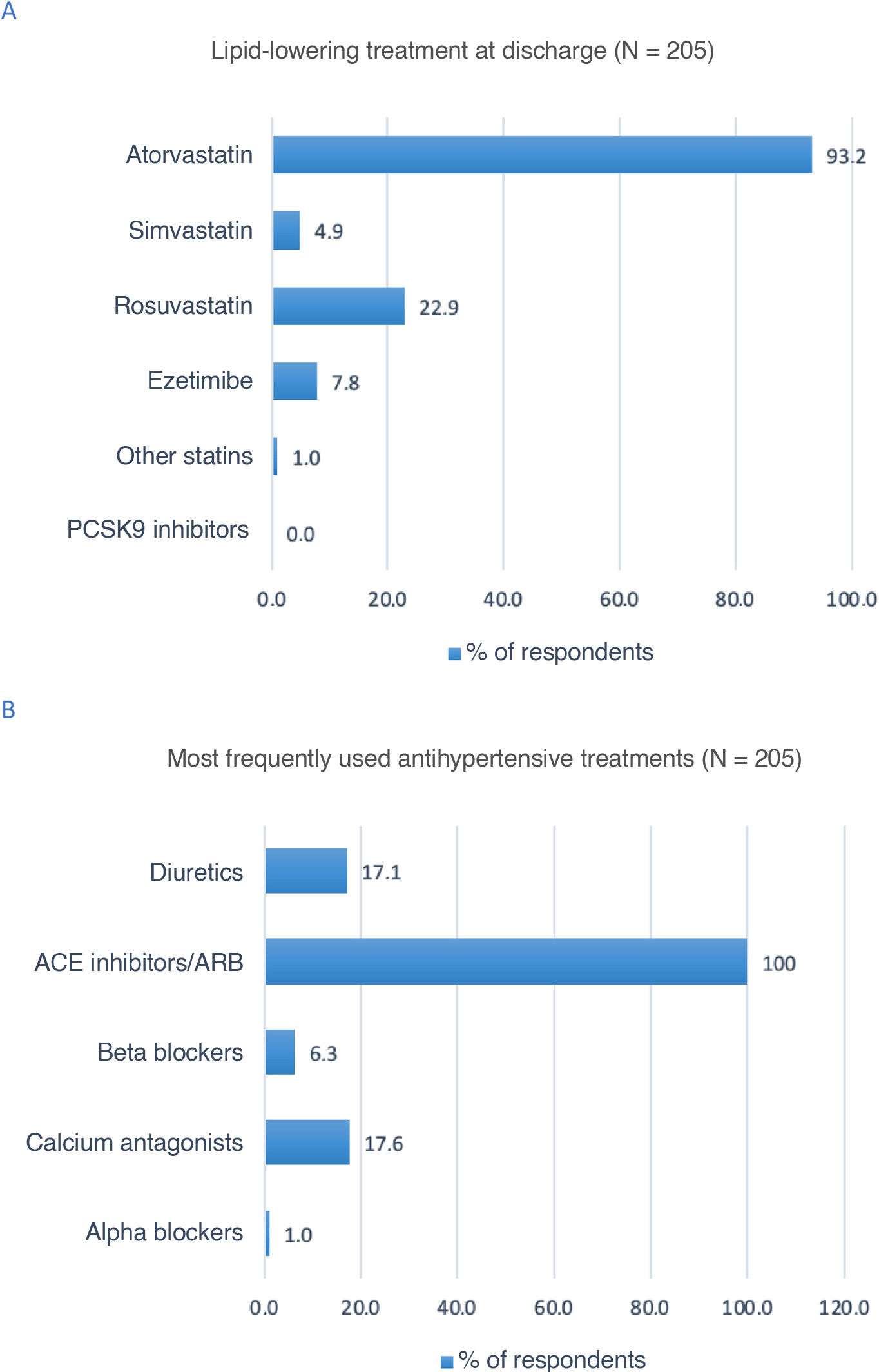

According to 93.2% of participants, atorvastatin was the lipid-lowering treatment most frequently prescribed at discharge (Fig. 3A). All respondents reported that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor II blockers were the most frequently prescribed antihypertensive drugs in patients with stroke (Fig. 3B).

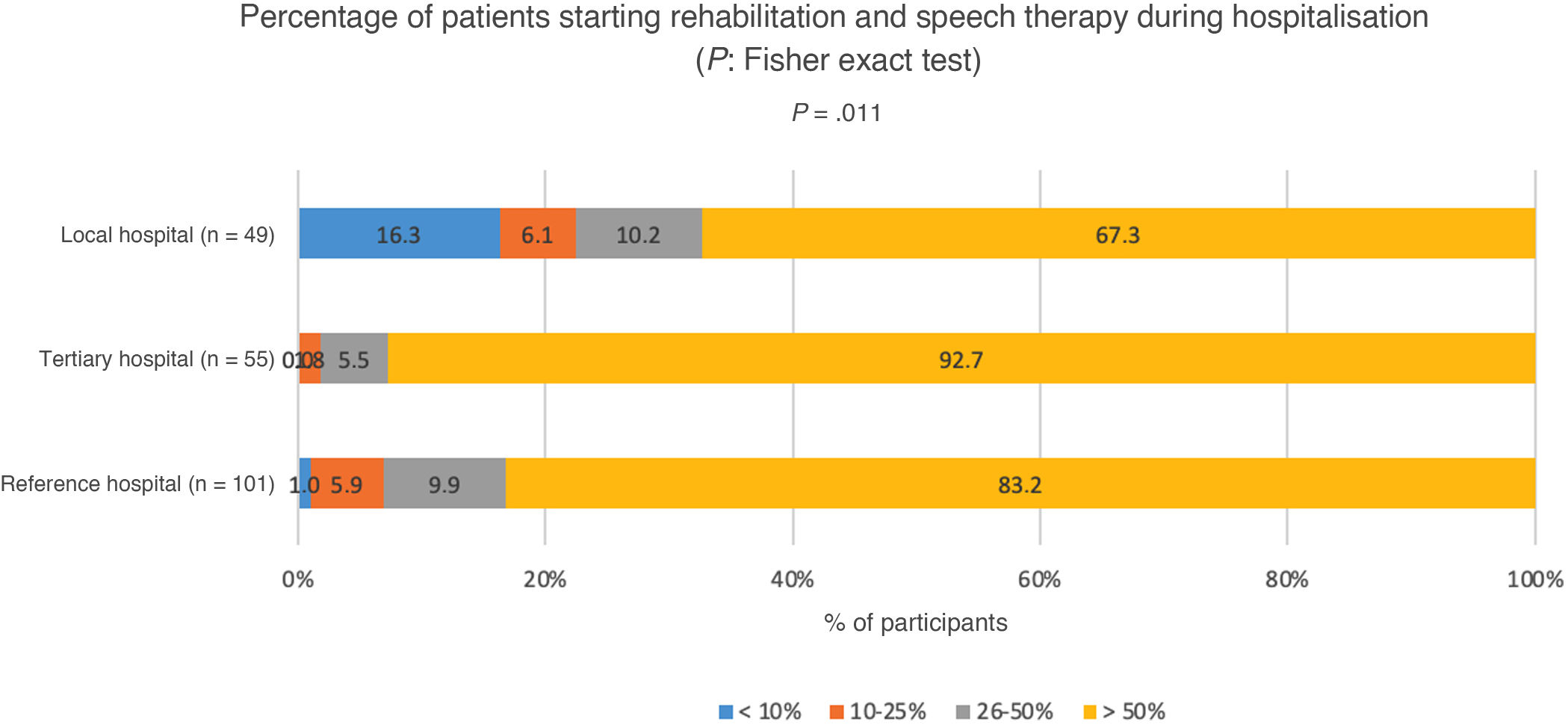

Rehabilitation and speech therapyOnly 4.4% of participants reported that fewer than 10% of patients with motor, speech, or swallowing sequelae started rehabilitation and speech therapy during hospitalisation; 4.9% reported rates of 10%–25%, 8.8% reported rates of 26%–50%, and 82.0% reported rates over 50%. In 92.7% of tertiary hospitals, over 50% of the patients started rehabilitation and speech therapy during hospitalisation; statistically significant differences were observed compared to other types of centres (P = .0011) (Fig. 4).

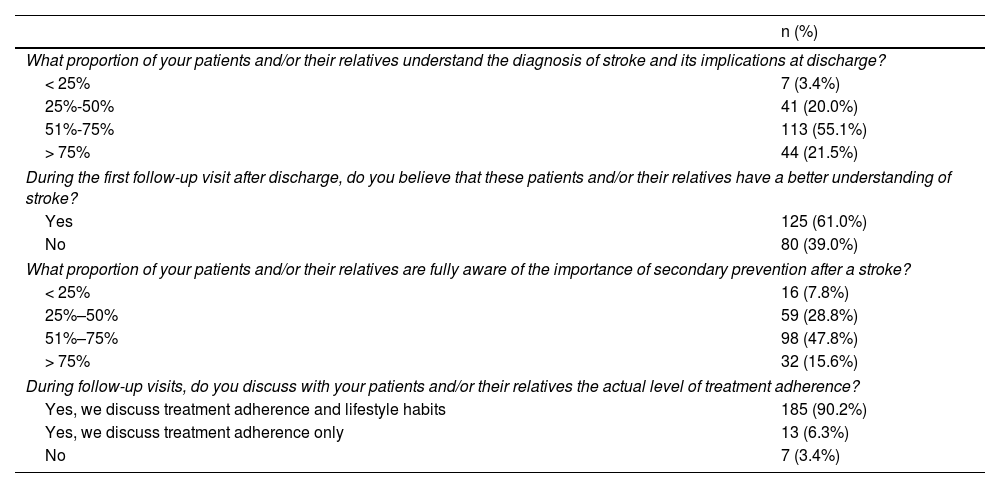

Additional assessmentsA total of 23.4% of participants reported that over half of patients and/or their relatives do not understand the diagnosis and its implications at the time of discharge. In contrast, 61% of participants believed that patients do understand the implications of their diagnosis at the time of the first follow-up visit, and 36.6% reported that less than half of patients and/or their relatives are aware of the importance of secondary prevention following stroke. Ninety percent of participants monitored treatment adherence and lifestyle habits at follow-up consultations, and 79.5% inquired about their patients’ mood (Table 5).

Assessment of patient mood, knowledge of stroke and its implications, and treatment adherence.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| What proportion of your patients and/or their relatives understand the diagnosis of stroke and its implications at discharge? | |

| < 25% | 7 (3.4%) |

| 25%-50% | 41 (20.0%) |

| 51%-75% | 113 (55.1%) |

| > 75% | 44 (21.5%) |

| During the first follow-up visit after discharge, do you believe that these patients and/or their relatives have a better understanding of stroke? | |

| Yes | 125 (61.0%) |

| No | 80 (39.0%) |

| What proportion of your patients and/or their relatives are fully aware of the importance of secondary prevention after a stroke? | |

| < 25% | 16 (7.8%) |

| 25%–50% | 59 (28.8%) |

| 51%–75% | 98 (47.8%) |

| > 75% | 32 (15.6%) |

| During follow-up visits, do you discuss with your patients and/or their relatives the actual level of treatment adherence? | |

| Yes, we discuss treatment adherence and lifestyle habits | 185 (90.2%) |

| Yes, we discuss treatment adherence only | 13 (6.3%) |

| No | 7 (3.4%) |

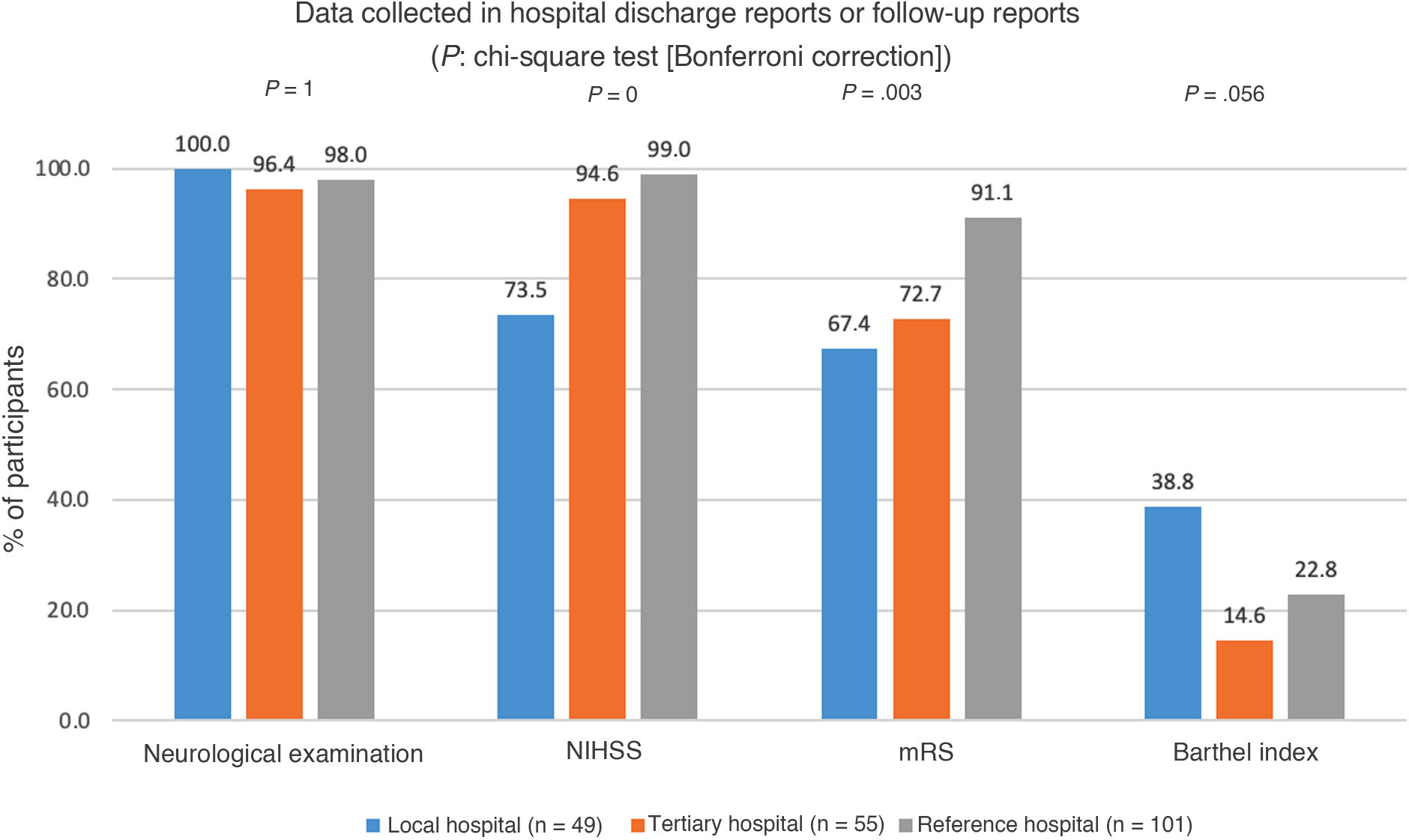

A total of 98.1% of participants reported systematically including neurological examination results in the discharge report or in follow-up reports; 91.7% included the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, and 80.5% included the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score. Statistically significant differences between types of healthcare centres were observed in the percentage of participants who included NIHSS and mRS scores (Fig. 5).

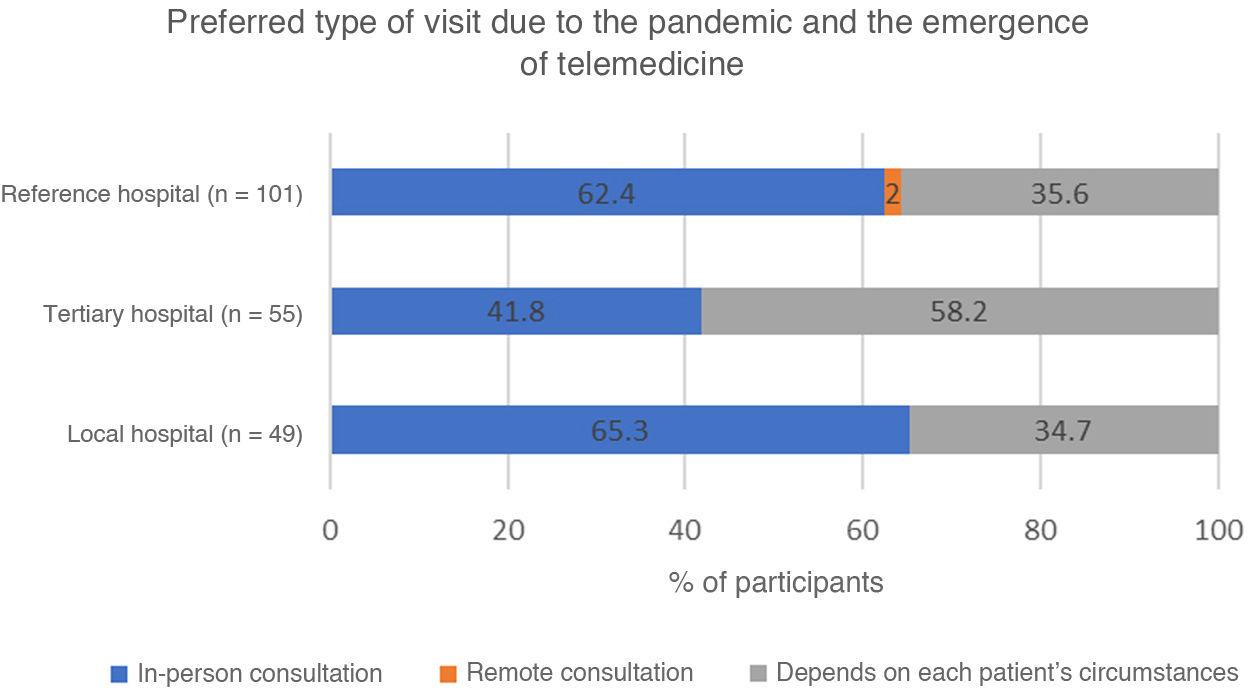

Participants were also asked about their preferences regarding the modality of follow-up consultations: 57.6% preferred in-person consultations and 41.5% made this decision according to each patient’s circumstances. Prioritisation of in-person consultations was significantly less frequent among participants from tertiary hospitals (Fig. 6).

DiscussionOur results highlight the lack of resources allocated to stroke care. More than one in 10 neurologists reported that their hospitals did not have a specific stroke care protocol, and one in 3 reported the lack of a dedicated stroke clinic. This is probably due to the shortage of neurology specialists in the Spanish healthcare system and the lack of specific training in cerebrovascular disease. Less than 60% of healthcare centres had a stroke unit, despite the fact that international stroke management guidelines underscore the need for all stroke patients to be attended at stroke units.8–10 Stroke teams serve as an alternative to stroke units, but they lack neurology specialists and have considerably fewer human, material, and technical resources, which has an impact on patient management and follow-up.7

Our study also provides insights into the management of some of the stroke sequelae with the greatest socioeconomic impact, as well as the secondary prevention measures implemented. Cognitive impairment is common after stroke, and has a significant functional, social, and family impact. In many cases, it may progress to vascular dementia, with incidence rates ranging from 6% to 32%.15,16 The criteria for attributing cognitive impairment to stroke include a time window of 6 months from the event.17 However, the literature on the subject is controversial, as strategic infarcts may affect cognitive regions that are recoverable within this time window. In fact, some patients who initially score poorly on cognitive tests during the acute stage have been found to improve significantly after several weeks.17 Likewise, cognitive assessment during the acute stage may be influenced by such other factors as hospitalisation, treatment initiation or adjustment, or language alterations; some authors suggest waiting at least 6 months before cognitive sequelae can be considered to be fully established. Although cognitive stimulation measures should be initiated early, reassessment at 3–6 months after the event may contribute to determining whether cognitive impairment persists and to establish the most appropriate rehabilitation measures, if necessary. From an epidemiological viewpoint, the incidence of post-stroke dementia or cognitive impairment (without considering other causes of vascular dementia) ranges from 7.4% to 41.3%.17,18 Furthermore, stroke itself is associated with a ninefold increase in the risk of dementia; previous history of cerebrovascular disease also contributes greatly to the risk of cognitive impairment or dementia following an acute vascular event.17–19

Early detection of cognitive impairment in the acute stage is essential in establishing early cognitive rehabilitation or treatment. In fact, international guidelines recommend routine cognitive screening following stroke.17,20,21 However, in our study nearly two-thirds of neurologists reported that they do not assess cognitive function, regardless of the type of healthcare centre. Similarly, the use of specific tools for cognitive assessment is recommended.18,22 In our study, the most frequently used tool was the MMSE, followed by the clock-drawing test. The clock-drawing test is a rapid, easy to use, and affordable tool for detecting markers of cognitive impairment in different stages.23 Although the MMSE is also easy and quick to administer, and most neurologists are familiar with it, it is progressively being replaced by other tools due to the potential effect on scores of depression, disability, illiteracy, and use of certain medications, which represents a major limitation.24 Several authors have proposed that the MMSE should be replaced by the MoCA, which has greater sensitivity.25–27 In our study, however, over 60% of participants did not use the latter tool. Approximately half of our participants reported using the Fototest, with a significantly greater proportion in tertiary hospitals. This tool is quick to administer and presents similar or superior discriminant validity to other tests, in addition to being suitable for illiterate individuals and those with low education levels.28 In fact, nearly 70% of our participants reported using this tool for this patient population.

Non-pharmacological cognitive interventions are strongly supported by clinical practice guidelines and the growing body of evidence showing changes in brain activation patterns and neuronal plasticity associated with these approaches in patients with mild cognitive impairment.19,29 In our study, the preferred location for cognitive stimulation was the patient’s home, followed by day centres. The pharmacological treatments most frequently recommended by the participating neurologists were acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and citicoline. The available evidence supports the short- and medium-term benefits of citicoline for cognition and behaviour in patients with vascular cognitive impairment,30 as well as its usefulness in the prevention of post-stroke cognitive impairment, with reported improvements in orientation, attention, and executive function.31 More neurologists from local hospitals than neurologists from tertiary or reference hospitals considered citicoline to be a good or very good treatment option, although the difference was not statistically significant. In line with this finding, early treatment for cognitive impairment was more frequently reported at local hospitals. Treatment with memantine was considered a good or very good option by over half of the participating neurologists, probably due to the considerable percentage of patients with mixed dementia, which combines Alzheimer-type pathology with vascular dementia.

The available evidence supports early initiation of rehabilitation therapy; its intensity and frequency are key considerations in achieving optimal recovery after stroke.32 In our study, however, a large proportion of neurologists, and especially those from local hospitals, reported that they rarely initiated rehabilitation and speech therapy during hospitalisation. This reflects the scarcity of resources allocated to post-stroke rehabilitation, particularly at local hospitals, which may have a major impact on the severity of stroke sequelae.

This study also addressed the secondary prevention of stroke. According to our results, knowledge of stroke and its secondary prevention is insufficient in the Spanish population. Our participants reported that one in 4 patients do not fully understand the event and have poor knowledge regarding secondary prevention after discharge.

Nearly all participants reported that over half of their patients present VRFs that require monitoring, although over 10% reported that they did not monitor VRFs. Appropriate anticoagulant therapy is essential for decreasing the risk of cerebrovascular events in patients with atrial fibrillation, a condition associated with 5 times greater risk of stroke. However, 40%–55% of patients receiving vitamin K antagonists (VKA) present poor INR control.33 In our study, neurologists from tertiary hospitals more frequently relied on primary care for patient monitoring and follow-up. Direct oral anticoagulants present higher efficacy in preventing thromboembolic events and a lower risk of intracranial haemorrhage than VKAs.34,35 However, such factors as age or kidney function may require dose adjustment. Participants working at reference hospitals more frequently reported systematic monitoring of these factors. Lipid-lowering and antihypertensive drugs are also essential in the management of patients with hyperlipidaemia and arterial hypertension, respectively. The vast majority of participants agreed that atorvastatin is the first line of treatment for hyperlipidaemia, whereas all participants reported that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor II blockers constitute the standard treatment for arterial hypertension.

Our study has several limitations, including those arising from the use of a non-probability sampling method. Furthermore, questions regarding respondents’ opinions, attitudes, and behaviours were presented with pre-established response options, which may have introduced bias by excluding other potential responses and limiting the opportunity to provide personal comments or explanations. However, the survey was designed by a scientific committee with sufficient expertise to include the most relevant or frequent response options. Lastly, there is a possibility that participants may have interpreted questions or response options differently.

ConclusionsAlthough the quality of neurological care and neurology professionals at Spanish hospitals is unquestionable, it is precisely this excellence that drives us to seek to identify potential areas for improvement. This study has identified several areas for improvement, including the generalisation of stroke units, the use of stroke protocols, and the implementation of stroke clinics, all of which could have a positive impact on the diagnosis, treatment, and secondary prevention of stroke. Communication with patients and their families should be strengthened, as treatment adherence and VRF monitoring are of critical importance. It is equally important to establish monitoring committees at all hospitals, with a view to evaluating the progress made in the areas for improvement identified by this study and monitoring the implementation of corrective measures.

Ferrer provided funding for this study, but did not exert any influence on its contents or the interpretation of our results.