To prospectively study the rate of consultation, diagnoses, burden and historical management patterns of those patients attending due to primary headache in Primary Care.

Patients and methodsWe included 200 patients with primary headache in a semi-urban Health Center. To study the consultation impact, 100 patients were consecutively recruited in one primary care quota. For every patient we obtained demographic data, comorbidities, rate of consultation, absenteeism, impact in quality of life (MIDAS and HIT-6 scales) and previous patterns of referral and treatment.

ResultsA total of 2.2% of the demand consultations were due to primary headache. Migraine (60%) was the most frequent reason, followed by tension-type headache (38.5%) and trigeminal autonomic headaches (1.5%). In 58% of cases the diagnosis was incomplete or incorrect. Between 33% (MIDAS) and 50.8% (HIT-6) of cases showed at least a moderate decrease in their quality of life, which was higher for migraine (40.8% and 72.5%, respectively). There was absenteeism in 12% of patients the last year (in 87.5% of cases due to migraine). More than half (58%) of cases had been referred to Neurology and preventive treatments had been initiated in Primary Care in only 5.5% of patients.

ConclusionsPrimary headaches, and mainly migraine, are a frequent reason for consultation in Primary Care. Even though migraine induces a significant absenteeism and damages quality of life, there is a clear room for improvement in their management. Primary headaches should be included in the health plans of Primary Care.

Estudiar de forma prospectiva la tasa de consulta, diagnósticos, impacto y patrones históricos de manejo de los pacientes que consultan por cefalea primaria en un Centro de Salud.

Pacientes y métodosRecogimos 200 pacientes con cefalea primaria en un Centro de Salud semiurbano. Para estudiar el impacto en consulta, 100 fueron recogidos consecutivamente en un único cupo. Para todos los pacientes recogimos datos demográficos, comorbilidades, frecuentación, absentismo, impacto en calidad de vida (escalas MIDAS y HIT-6) y de patrones previos de derivación y tratamiento.

ResultadosUn 2,2% de las consultas a demanda se debieron a cefalea primaria. La migraña (60%) fue la causa más frecuente, seguida de la cefalea tensional (38,5%) y las cefaleas trigémino-autonómicas (1,5%). En el 58% de los casos el diagnóstico o estaba incompleto o era incorrecto. Entre el 33% (MIDAS) y el 50,8% (HIT-6) presentaban afectación al menos moderada en su calidad de vida, que fue superior en la migraña (40,8% y 72,5%, respectivamente). Hubo absentismo en el 12% de los pacientes el último año (en 87,5% por migraña). Algo más de la mitad (57%) habían sido derivados a Neurología y solo el 5,5% de los tratamientos preventivos se habían iniciado en el primer nivel asistencial.

ConclusionesLas cefaleas primarias, y fundamentalmente la migraña, son motivo frecuente de consulta en Atención Primaria. A pesar de que la migraña condiciona un absentismo significativo y que daña la calidad de vida, existe un claro margen de mejora en su manejo. Las cefaleas primarias deberían ser incluidas en los planes de salud del primer nivel asistencial.

Headache is the most frequent reason for consultation with neurology departments, accounting for 20%-25% of all first consultations. Most of these consultations are due to primary headaches, with migraine being by far the most frequent diagnosis.1

A very preliminary study conducted by our research group found that over 90% of patients who visited a healthcare centre due to headache met criteria for primary headache.2 In contrast with what has been reported for neurology departments,1,3 no prospective data are available in Spain regarding the diagnostic distribution and the real impact of primary headaches on primary care consultations in our setting. Although primary headaches are not severe from a clinical viewpoint, they represent a major healthcare problem due to their high prevalence and negative impact on quality of life.4,5 They also cause a considerable social burden in developed countries. However, headache is frequently regarded as an unattractive reason for consultation with primary care as it is considered a minor problem.6 Some studies have underscored the need to improve training in headache diagnosis and management at this level of care. Part of the problem lies in the fact that migraine is frequently misdiagnosed as tension-type headache, given that the latter is more prevalent in the general population.7

In the light of the above, there is a need to gather data on primary headaches in primary care in Spain. The purpose of this study was to prospectively analyse the consultation rate, diagnostic distribution, impact on quality of life, and general management guidelines for patients consulting with their primary care physician due to primary headache.

Patients and methodsThis study was conducted at the Bezana healthcare centre, in Cantabria, and included patients over the age of 15 years. It was approved by the ethics committee of the region of Cantabria, and all participants gave written informed consent. The Bezana healthcare centre, located in a semi-urban area, provides care to a total population of 11 026 individuals over the age of 15 years (5676 women and 5350 men). To address the 2 objectives presented above, we established a target sample of 200 patients consulting for primary headache. To evaluate the frequency of primary headache disorders as a reason for consultation and their diagnostic distribution, this prospective study included up to 100 consecutive patients from a single patient population of 1600 individuals, who consulted due to headache and were diagnosed with a primary headache disorder during the study period. Patients who had consulted previously due to headache were not excluded. To gather additional information on the diagnostic distribution of primary headaches in primary care, we also collected data from a further 100 patients consulting due to headache who belonged to other patient populations attended at our healthcare centre during the study period.

Recruitment began in May 2019 and was stopped on 1 March 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, when 181 patients had been recruited. To gather the pre-established sample size of 200 patients, patient recruitment was resumed on May 2020, and was completed a month later.

Patient medical histories were taken by one of the participating primary care physicians (IR, LC, or NF). Detailed medical histories were taken and a physical examination was performed, and electronic medical records from primary care were reviewed. Headache diagnosis was based on the 2018 version of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD).8 In the event of diagnostic uncertainty, patients were evaluated by a neurologist specialising in headache (JP). The following variables were collected: age, sex, drug habits, body mass index, and comorbidities. We also gathered data on the number of consultations with primary care over the past year (including emergency consultations with primary care), referrals to secondary care, complementary studies, medical leave, impact of primary headache on quality of life as assessed with the Headache Impact Test (HIT-69 and the Migraine Disability Assessment Score (MIDAS),10 and symptomatic and preventive treatments.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistics software. Variables are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages. We used the t test for statistical analysis, as the variables analysed followed a normal distribution. Values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsWe included 100 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of primary headache from a single patient population over a period of 10.6 months. This period comprised 212 effective consultation days, yielding a mean of 0.47 patients per day consulting due to primary headache. The mean number of daily consultations for this patient population was 36. After excluding visits for administrative purposes and scheduled health check-ups, the mean number of unscheduled consultations for illness was 21 per day (4452 over the period of 10.6 months). Therefore, 2.2% of unscheduled primary care consultations were due to primary headache disorders. This percentage is higher if we consider the fact that, during the study period, 59 of these 100 patients spontaneously consulted with their healthcare centre and 29 patients visited the emergency department for migraine treatment on more than one occasion.

To better characterise the profile of patients consulting with primary care for primary headache, we increased the sample to 200 patients, including an additional 100 patients drawn from other practices within the same healthcare centre. No significant differences were found in any parameter (demographic, diagnostic, etc) between the initial 100 patients and the additional 100. The total sample of 200 patients included 162 women (81%), and the mean (SD) age was 42.7 (13) years (range, 16-83). Regarding diagnostic distribution, 120 patients (60%) met diagnostic criteria for migraine, 77 (38.5%) for tension-type headache, and 3 (1.5%) for trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Among the 120 patients with migraine, 16 (8% of the total sample) met criteria for chronic migraine, and 8 of the 77 patients with tension-type headache (4%) met criteria for chronic tension-type headache. Half of the patients with chronic migraine (n = 8; 4%) and chronic tension-type headache (n = 4; 2%) met criteria for analgesic overuse.

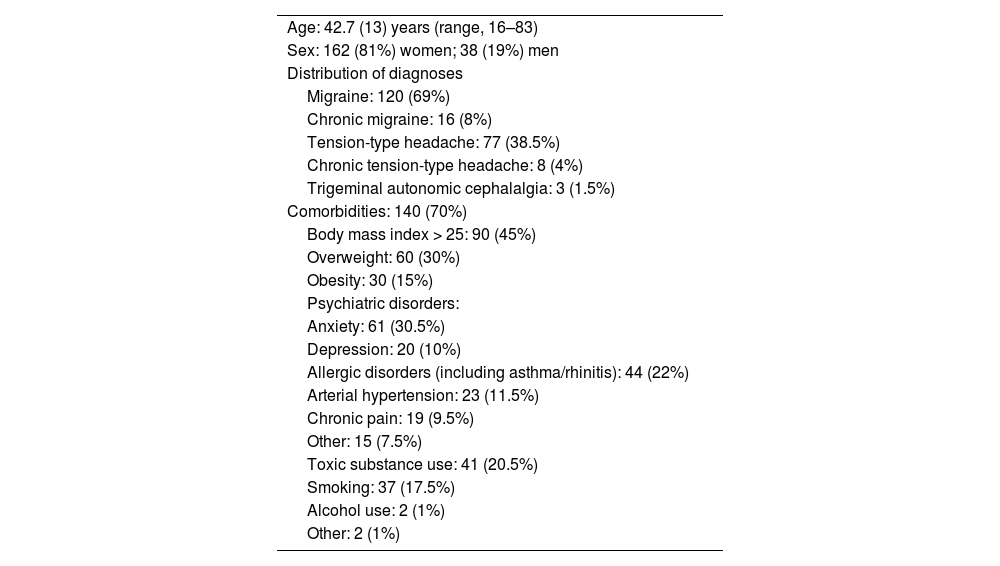

In 116 patients (58%), the diagnosis recorded in the electronic medical record was either incomplete or incorrect. In 103 of these (88.8%), no headache diagnosis was recorded, or the diagnosis was simply “headache,” without specifying the type, whereas the remaining 13 (11.2%) were diagnosed incorrectly according to the ICHD criteria.8 Specifically, 8 had been diagnosed with migraine but met diagnostic criteria for tension-type headache, 4 had been diagnosed with tension-type headache but met criteria for migraine, and one had been diagnosed with migraine but met criteria for trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia. A total of 140 patients (70%) presented significant comorbidities (Table 1).

Characteristics of our sample of patients with primary headache disorders.

| Age: 42.7 (13) years (range, 16–83) |

| Sex: 162 (81%) women; 38 (19%) men |

| Distribution of diagnoses |

| Migraine: 120 (69%) |

| Chronic migraine: 16 (8%) |

| Tension-type headache: 77 (38.5%) |

| Chronic tension-type headache: 8 (4%) |

| Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia: 3 (1.5%) |

| Comorbidities: 140 (70%) |

| Body mass index > 25: 90 (45%) |

| Overweight: 60 (30%) |

| Obesity: 30 (15%) |

| Psychiatric disorders: |

| Anxiety: 61 (30.5%) |

| Depression: 20 (10%) |

| Allergic disorders (including asthma/rhinitis): 44 (22%) |

| Arterial hypertension: 23 (11.5%) |

| Chronic pain: 19 (9.5%) |

| Other: 15 (7.5%) |

| Toxic substance use: 41 (20.5%) |

| Smoking: 37 (17.5%) |

| Alcohol use: 2 (1%) |

| Other: 2 (1%) |

The impact of primary headache disorders on quality of life is presented in Figs. 1 and 2. According to the MIDAS, headache had at least moderate impact (> 10 points) on quality of life in 33% of patients. This percentage was significantly higher (P = .0) among patients with migraine (40.8%) than among those with tension-type headache (20.7%). A similar pattern was observed with HIT-6 scores, with 102 patients (51.8%) reporting a substantial or severe impact on their quality of life (> 56 points). Of these, 28 patients had tension-type headache (27.5% of patients scoring > 56 points on the HIT-6) and the remaining 74 (72.5%) had migraine (P = .001).

A total of 24 patients (12%) required medical leave over the past year due to headache, with a mean duration of 4 days (median: 3; range, 1-21). Leave was due to migraine in 21 cases (87.5%), tension-type headache in 2 (8.3%), and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia in the remaining case (4.2%). The mean duration of leave among patients with migraine was 3.2 days (median: 2; range, 1-15). Therefore, in the primary care setting, each patient with migraine is absent from work for a mean of 0.34 days per year.

Of the 200 patients evaluated in our study, 114 (57%) had previously been referred to the neurology department, and 81 (40.5%) had undergone neuroimaging studies (head CT [60.5%], brain MRI [24.7%]).

A total of 199 patients (99.5%) had previously received symptomatic treatment for their headache disorder. Fig. 3 shows the distribution of treatment by pharmacological group and diagnosis. Eighty-five patients (42.5%) had previously received preventive treatment; in only 11 cases (5.5%) had this treatment been prescribed by a primary care physician. Sixty-nine patients (34.5%) met eligibility criteria for preventive treatment at the time of the consultation, but only 34 of them (49%) were actually receiving it: amitriptyline in 19 (55.9%), beta-blockers in 13 (38.2%), topiramate in 9 (26.5%), and flunarizine in 2 (5.9%).

DiscussionOur results confirm that primary headache disorders have a significant impact on the primary care level in our setting. Firstly, 2.2% of spontaneous consultations (that is excluding visits for administrative purposes and scheduled health check-ups) in a standard patient population from a healthcare centre in Spain were due to primary headache disorders. Considering the mean number of patients attended per day, this means that primary care physicians will attend one patient consulting for primary headache every 2-3 days. This figure may actually be higher, considering that more than half of our patients consulted on more than one occasion during the study period, and stands in contrast with the widespread idea that patients with primary headache do not seek medical attention.11 As shown in a macrostudy recently conducted in Spain, 80% of a sample of over 10 000 patients with migraine had consulted with their primary care physician due to primary headache in the past year.12

As in neurology departments,1,3 approximately 60% of consultations were due to migraine, just over one-third due to tension-type headache, and 1.5% due to trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Although tension-type headache is the most prevalent type of headache, our results confirm that migraine is the primary headache disorder that most frequently prompts consultation with primary care. Furthermore, one in every 8 patients consulting for migraine met criteria for chronic migraine, a condition that can drastically decrease quality of life, as has been shown in several studies conducted in our setting.13,14 Migraine, and particularly chronic migraine, has a significant impact in terms of both direct and indirect costs, as several studies conducted in Spain have shown.15,16 This is also reflected by quality of life questionnaires. Depending on the tool, between one-third (MIDAS9) and half of patients (HIT-610) in the total series experienced at least moderate impact on their daily living activities, although the proportion of patients experiencing at least a moderate decrease in quality of life was, once again, significantly greater in those with migraine than in those with tension-type headache. The explanation for this is straightforward: as repeatedly noted by the World Health Organization, migraine is one of the most disabling conditions for daily living activities and should therefore be prioritised in health-care planning due to its high frequency and considerable personal, social, and healthcare impact.5 In this regard, an important finding from our study was the impact of headache disorders in terms of workplace absences: 12% of patients from the total series reported medical leave due to headache in the previous year, with a mean duration of 4 days. Again, the vast majority of patients requiring medical leave presented migraine, which confirms that this condition has a more severe impact at all levels than tension-type headache. The rate of workplace absence due to migraine in our study is similar to those previously reported in Spain and other European countries.17

Our study also analysed several noteworthy aspects of headache management in primary care. Interestingly, 60% of patients either had not received a diagnosis of the specific type of primary headache or had been misdiagnosed; this has previously been reported in the literature.7,12 This may explain why some patients with tension-type headache were receiving symptomatic medications for migraine (Fig. 3), why one in every 4 patients with migraine were not receiving triptans (the treatment of choice for migraine according to the current guidelines in our setting), and why some patients with migraine had received drugs of very doubtful efficacy for this indication, such as paracetamol.18,19 Likewise, we were surprised to find that over half of patients with headache disorders had been referred to a neurology specialist, and that the rate of preventive treatment prescription in primary care was low (5.5%).

This study has several limitations, including its relatively small sample size and the fact that the diagnostic rate was obtained in a single patient population at a primary healthcare centre; however, this approach ensures that no cases were missed. Furthermore, the pandemic may have had an impact on our results; however, any such effect is likely to have been minimal, since 9 out of 10 patients were recruited before the pandemic. In any case, our results underscore the need to implement action plans for the management of headache in general, and migraine in particular, in primary care, given that most patients with primary headache disorders should receive initial treatment at their primary care centre.1,6,17–20

ConclusionsPrimary headaches, and especially migraine, are a frequent reason for consultation with the primary care physician. Although migraine results in a significant rate of workplace absence and has a negative impact on quality of life, there is considerable room for improvement in its management. Primary headache disorders should be integrated into primary care health plans.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We wish to thank our colleagues from primary care and their patients with headache from the Bezana healthcare centre for their collaboration.